Abstract

Purpose:

Advance care planning (ACP) in hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) is challenging, given the potential for cure despite increased morbidity and mortality risk.The aim of this study was to evaluate ACP and palliative care (PC) integration for patients who underwent HSCT.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis was conducted and data were extracted from electronic medical records of patients who underwent HSCT between January 2011 and December 2015. Patients who received more than one transplant and who were younger than 18 years of age were excluded. The primary objective was to determine the setting and specialty of the clinician who documented the initial and final code status. Secondary objectives included evaluation of advance directive and/or completion of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, PC consultation, hospice enrollment, and location of death.

Results:

The study sample comprised 39% (n = 235) allogeneic and 61% (n = 367) autologous HSCTs. All patients except one (n = 601) had code status documentation, and 99.2% (n = 596) were initially documented as full code. Initial and final code status documentation in the outpatient setting was 3% (n = 17) and 24% (n = 143), respectively. PC consultation occurred for 19% (n = 114) of HSCT patients, with 83% (n = 95) occurring in the hospital. Allogeneic transplant type and age were significantly associated with greater rates of advance directive and/or Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment completion. Most patients (85%, n = 99) died in the hospital, and few were enrolled in hospice (15%, n = 17).

Conclusion:

To our knowledge, this is the largest single-center study of ACP and PC integration for patients who underwent HSCT. Code status documentation in the outpatient setting was low, as well as utilization of PC and hospice services.

INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) is a high-risk procedure, with treatment goals focused on a potential cure even in advanced or high-risk disease. This is in contrast to patients with metastatic solid tumors, for whom the chance of cure is rarely possible. Consequently, advance care planning (ACP), the process whereby individuals communicate their end-of-life treatment preferences to their clinicians and caregivers in the event of decisional incapacity, is particularly challenging in patients who undergo HSCT. Further complicating ACP in this setting is determining the appropriate time and setting to initiate ACP discussions. Ideally, ACP should occur early in the nonemergent, outpatient setting with well-known and trusted clinicians, yet HSCT clinicians themselves note difficulty in initiating these discussions.1 In fact, the majority of these HSCT clinicians believe that ACP discussions occur too late, with many discussions occurring only when death is imminent.1

Studies suggest an overall quality gap in palliative care (PC) for patients who undergo HSCT compared with solid tumor patients. Patients who undergo HSCT are more likely to die in the hospital, receive chemotherapy at the end of life, and are less likely to receive PC referrals.1-14 Despite evidence that supports early ACP and PC integration for advanced solid tumor cancers, there are sparse, but growing, data in patients who undergo HSCT.8,11,15-18 For example, Selvaggi et al8 conducted a quality improvement project to identify gaps between PC and HSCT services through a needs assessment, didactic lectures, clinical consultation, and the informal presence of PC clinicians. In 256 unique patients, 70% reported unacceptable pain at baseline, which improved to acceptable levels for more than half of patients within 2 days of PC consultation. In addition, the PC team completed and documented the first incidence of ACP in 70% of patients who underwent HSCT. For those patients who died, hospice referrals increased from 5% to 41%, with clinicians reporting high levels of satisfaction with the program.8 Most recently, El-Jawahri et al18 presented results from a randomized trial that provides the strongest evidence to date for integrating PC specialists throughout the duration of curative treatments for patients undergoing HSCT. This single-center clinical trial included 160 adults (mean age, 60.1 years) who were hospitalized for HSCT. Patients were randomly assigned to either a PC intervention integrated with usual care (n = 81) or usual care alone (n = 79). Patients who underwent HSCT in the PC group were seen by PC clinicians at least twice per week during hospitalization, who focused primarily on addressing physical and psychological symptoms. The patients who were randomly assigned to the early, 2-week PC arm showed improved quality of life (QoL) and mood that extended to 3 months after the intervention was completed.18 Consequently, we evaluated PC integration for patients undergoing HSCT at our institution. The aim of this study was to evaluate ACP and PC integration for patients undergoing HSCT.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review was conducted at a single, academic, comprehensive cancer center of patients who underwent HSCT. Institutional review board study approval was granted by the Human Research Protections Program at the University of California (UC), San Diego. The Doris A. Howell Palliative Care Service was founded at UC San Diego in 2005 by Charles von Gunten. Its initial focus was on patients who underwent HSCT who were located in a distinct inpatient unit within UC San Diego’s Thornton Hospital. In 2014, there were 143 SCTs and 585 PC encounters among patients who underwent HSCT at our institution.13

Data were extracted from a single electronic medical record of patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent HSCT between January 2011 and December 2015. Data were extracted up to January 15, 2016. Patients who received more than one transplant were excluded from analysis. Patients younger than 18 years of age were also excluded. Code status data were collected by searching the entire electronic medical record through use of a search feature for key terms such as “code status,” “full code,” “DNR,” “DNAR,” and “comfort care,” which pulled up, in chronological order, all prior notes and orders containing the search terms documented within the electronic medical record. These data were then compared with and confirmed with the inpatient admission code status. The inpatient admission code status lists the code statuses for all inpatient admissions, including code status changes while the patient is admitted to the hospital. Code status documentation, date documented, and author were further clarified by reviewing the electronic medical record. Advance directive (AD) and Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatments (POLST) data were collected by including data found under the media tab for scanned AD and/or POLST documents. If no scans were found, then “advance directive” and “POLST” were searched for in the entire medical record using the search function. Other secondary objective data were similarly collected using the search terms “palliative,” “Howell” (namesake of PC service), and “hospice.”

Demographic data, including age at transplant, sex, cancer diagnosis, and type of HSCT, were collected. HSCTs were differentiated between autologous and allogeneic. Allogeneic HSCTs included matched related donor, matched unrelated donor, mismatched, cord blood, and haploidentical. Variables analyzed and/or collected included initial code status documentation, AD and/or POLST completion, PC consultation, hospice enrollment, date of most recent transplant, location of death, and date of death. For patients who were alive as of January 15, 2016, the last code status was the most recent documented code status in the electronic medical record. For patients who died on or before January 15, 2016, the last code status was the documented code status as of the date of death. For patients who underwent HCST and died, we calculated the time between date of death and date of transplant, as well as the time between date of death and date of AD/POLST completion.

The nonparametric, Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the difference in time from date of transplant to date of death between transplant types. Univariable logistic regression models examined associations of transplant type, age, and sex with AD/POLST completion and PC consultation. Variables that were significantly associated with AD/POLST completion or PC consultation were examined together in multiple logistic regression models. Results of the logistic regression models are reported in odds ratios (ORs) with accompanying 95% CIs. A P value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were two-sided. Data were collected in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 633 HSCTs for hematologic malignancies were performed between 2011 and 2015. After removal of patients who had a repeat transplant (n = 31), 602 patients were included in the analysis (Fig 1). Thirty-nine percent (n = 235) were allogeneic transplants, and 61% (n = 367) were autologous transplants. The mean age of patients who underwent SCT was 55 (± 13) years, and the majority of patients (62%) were men (n = 375; Table 1). All patients except one had an initial code status documentation (n = 601). Full code was the most common treatment preference and was documented in 99.2% of patients (n = 596). In the outpatient setting, initial code status was documented for 3% (n = 17), with the primary HSCT physician providing documentation for a single patient (Fig 1). The remaining outpatient code status documentation was completed primarily by interventional radiology, anesthesiology, or surgery nurse practitioners before procedures. The last code status documentation completed in the outpatient setting occurred in 3% of patients (n = 13) and by the primary HSCT physician for five patients.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of HSCT patients included in study. HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

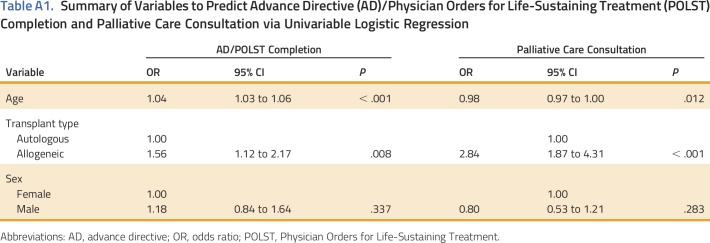

Nearly half (44%) of the patients who underwent HSCT (n = 267) had an AD and/or POLST completed. Logistic regression revealed that age (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.06; P < .001; Appendix Table A1, online only) and allogeneic transplant (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.17; P = .008) were positively associated with AD and/or POLST completion. Sex was not significantly associated with AD and/or POLST completion (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.64; P = .337). Multiple logistic regression, which modeled age and transplant type together, observed an almost two-fold greater odds of AD and/or POLST completion in patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.35 to 2.73; P = .003). The effect of age remained unchanged, with each 1-year increase associated with a 5% increase in odds of AD/POLST completion (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.06; P < .001).

PC consultation occurred for 19% of patients who underwent HSCT (n = 114). Rates differed significantly between transplant types, with 8% of patients who underwent autologous HSCT (n = 46) receiving a PC consultation compared with 11% of patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT (n = 68; P < .001). On the basis of primary hematologic malignancy, the majority of PC consultations were in patients with multiple myeloma (n = 31), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 28), and acute myelogenous leukemia (n = 22). The majority (83%) of PC consultations were completed in the hospital (n = 95) and 68% were requested by the inpatient HSCT team (ie, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, fellow physician, and/or attending physician; n = 82; Fig 2). The most common reason for PC consultation was symptom management (80%; n = 91). Simple logistic regression revealed that age (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.00; P = .012; Appendix Table A1) had a significant negative association with PC consultation completion; specifically, each 5-year increase in age was associated with an almost 9% lower odds of PC consultation. Allogeneic transplant type was associated with an almost three-fold increase in the odds of PC consultation (OR, 2.84; 95% CI, 1.87 to 4.31; P < .001). Sex was not significantly associated with PC consultation completion (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.53 to 1.21; P = .283). In a multiple logistic regression model that included age and transplant type, we observed a slightly attenuated association between transplant type and PC consultation (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.77 to 4.12; P < .001), whereas age at treatment was no longer significantly associated with PC consultation (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.00; P = .069).

Fig 2.

Specialties that consult palliative care. HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

As of January 2016, 116 patients who underwent HSCT had died, with a mean ± standard deviation days from transplantation to death of 281 ± 288 days. When stratified by transplantation type, the mean ± standard deviation days from transplantation to death was significantly longer in patients who underwent autologous HSCT (398 ± 360 days; n = 41) versus patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT (215 ± 214 days; n = 75; P < .05). Fifty-six of 116 patients (48%) received a PC consultation. Of those who died, the majority (85%; n = 99) died in the hospital and 15% (n = 17) were enrolled in hospice.

DISCUSSION

Smaller studies have looked at similar aspects of ACP and PC referrals in patients who undergo HSCT and have suggested a quality gap in end-of-life care.4,5,8,10,19,20 To our knowledge, this is the largest study published to date contributing to the growing body of evidence of ACP and PC integration with HSCT. Patients who undergo HSCT are unlikely to have ACP discussions with their oncologists and are less likely to use PC or hospice services than patients with advanced solid tumors. Patients who undergo HSCT are more seriously ill at admission to hospice, with worse functional status, and shorter hospice lengths of stays.21 Our data support these findings and add to the growing body of literature about ACP, PC integration, and hospice use within HSCT.

ACP is an ongoing process. It should start early and be routinely revisited throughout the transplantation course. Prior studies in HSCT have demonstrated that early pretransplantation, ACP does not negatively impact hope and correlates with improved survival after transplantation.3,6 Ideally, patients who undergo HSCT and their selected medical surrogates will engage in informative discussions with their clinicians that lead to the completion of ADs and/or POLSTs. However, code status documentation and/or AD/POLST completion in itself is not the end-all. Informative ACP discussions are the real key, but conversations are difficult to measure retrospectively. In measuring surrogate markers of ACP, including code status documentation and AD/POLST completion, our data suggest that ACP for patients who undergo HSCT occurs primarily in the inpatient setting. The trigger for code status documentation in the patients who undergo HSCT seems to be hospital admission, which requires a code status order. Required code status orders for hospitalization may not be reflective of an in-depth ACP discussion, especially when code status orders were most frequently completed by members of the inpatient SCT team and/or hospitalists/clinicians least familiar with the patient. In this study, rates of outpatient initial and final code status documentation were low, at 3% and 25%, respectively. These results support previous studies22,23 that reported low rates of code status documentation in the outpatient setting. These findings highlight not just the importance of documentation, but the need to encourage such ACP discussions in the nonemergent outpatient setting.

In this study, age and allogeneic transplantation type were associated with an increase in the rate of AD/POLST completion. The observation that age had an impact on AD/POLST completion is not surprising, given that in the noncancer, primary care setting, older patients are more likely to complete an AD.24 To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies reporting rates of AD/POLST completion, as well as PC consultation completion, on the basis of transplantation type. However, caution is warranted when generalizing these findings given that this is a retrospective study at a single academic cancer center. Future studies with patients who undergo HSCT receiving care at different institutions and/or practice models are needed to confirm this study's findings.

Despite our active and growing PC service and unprecedented access to patients who undergo HSCT,13 we found that PC referrals were low and only occurred for 19% of these patients. The majority of PC consultations were completed in the inpatient setting, with few PC consultations occurring in the outpatient setting, paralleling a national trend.25 HSCT can be an arduous process, with substantial physical and psychological symptoms starting at hospitalization. Emerging data demonstrate that effective collaboration between the HSCT and PC teams may improve patient care and outcomes. Most recently, El-Jawahri et al18 presented data from a single-center, randomized controlled trial, demonstrating that early inpatient PC integration with standard care for patients with hematologic malignancy improved QoL and decreased physical and psychological symptoms compared with patients who received usual care. Most notable, it was the first study to evaluate PC integration within the curative setting.18 At our institution, we are identifying the challenges and barriers in accessing PC for patients undergoing HSCT, especially in the outpatient setting.

In support of prior studies indicating a quality gap in end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies, we also found that a minority (15%) of decedent patients who underwent HSCT received hospice care.19,20 Causative factors remain unclear and may include lack of ACP, PC integration, hospice utilization, unique treatment timelines, prognostic uncertainty, culture of care, and/or practical limitations. Consequently, patients who undergo HSCT do not enroll in hospice and die in the hospital.

As our understanding of treatment modalities for hematologic malignancies improves, so too must our ability to effectively incorporate methods and services to maximize QoL. We recognize that although data regarding PC integration demonstrate improved QoL and survival, as well as decreased health care–related costs in patients with advanced solid tumor malignancies, these findings may not extrapolate to hematologic malignancies. However, a growing body of evidence regarding PC integration with hematologic malignancies has spurred renewed interest.18 Ideally, data will lead to changes in models of care delivery and ultimately improve the care of patients undergoing HSCT and their loved ones. We hope that our findings highlight opportunities for earlier and improved integration of PC for patients undergoing HSCT and incite continued research focusing on early integrative models of PC delivery, especially within the outpatient setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

E.J.R. is supported by an Alliance Cancer Control Program Junior Faculty Award (UG1CA189823); University of California, San Diego Clinical Translational Research Institute KL2 Career Development Award (KL2TR001444); and Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholars Leadership Program. We thank our patients and colleagues. Presented at ASCO Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, San Francisco, CA, September 9-10, 2016.

Appendix

Table A1.

Summary of Variables to Predict Advance Directive (AD)/Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Completion and Palliative Care Consultation via Univariable Logistic Regression

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Joseph D. Ma, Carolyn Revta, Gary T. Buckholz, Carolyn M. Mulroney, Eric J. Roeland

Collection and assembly of data: Winnie S. Wang

Data analysis and interpretation: Winnie S. Wang, Joseph D. Ma, Sandahl H. Nelson, Carolyn M. Mulroney, Eric J. Roeland

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Advance Care Planning and Palliative Care Integration for Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Winnie S. Wang

No relationship to disclose

Joseph D. Ma

Stock or Other Ownership: Amgen

Sandahl H. Nelson

No relationship to disclose

Carolyn Revta

No relationship to disclose

Gary T. Buckholz

No relationship to disclose

Carolyn M. Mulroney

Stock or Other Ownership: Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pharmacyclics

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pharmacyclics

Eric J. Roeland

Honoraria: Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eisai (Inst), Helsinn Healthcare (Inst), HERON

Speakers’ Bureau: Eisai, Depomed

Research Funding: AstraZeneca (Inst), Merck (Inst), Depomed (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eisai, Helsinn Healthcare

REFERENCES

- 1.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron N, et al. : Timeliness of end-of-life discussions for blood cancers: A national survey of hematologic oncologists. JAMA Intern Med 176:263-265, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novik AA, Manikhas G, Ionova T, et al. : Comparison of symptom severity and prevalence between hematological malignancies and solid tumors among Russian oncology patients. Blood 100:496B, 2002. (abstr 5570) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganti AK, Lee SJ, Vose JM, et al. : Outcomes after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies in patients with or without advance care planning. J Clin Oncol 25:5643-5648, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joffe S, Mello MM, Cook EF, et al. : Advance care planning in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 13:65-73, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D, Didwaniya N, Vidal M, et al. : Quality of end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer 120:1572-1578, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loggers ET, Lee S, Chilson K, et al. : Advance care planning among hematopoietic cell transplant patients and bereaved caregivers. Bone Marrow Transplant 49:1317-1322, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odejide OO, Salas Coronado DY, Watts CD, et al. : End-of-life care for blood cancers: A series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract 10:e396-e403, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selvaggi KJ, Vick JB, Jessell SA, et al. : Bridging the gap: A palliative care consultation service in a hematological malignancy-bone marrow transplant unit. J Community Support Oncol 12:50-55, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, et al. : Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med 17:195-199, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. : Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer 121:951-959, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeBlanc TW, O’Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. : Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: A mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract 11:e230-e238, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29430. El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al: Health care utilization and end-of-life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 121:2840-2848, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roeland E, Ku G: Spanning the canyon between stem cell transplantation and palliative care. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2015:484-489, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loggers ET, LeBlanc TW, El-Jawahri A, et al. : Pretransplantation supportive and palliative care consultation for high-risk hematopoietic cell transplantation patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22:1299-1305, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1438-1445, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein AS, Goldberg GR, Meier DE: Palliative care and hematologic oncology: The promise of collaboration. Blood Rev 26:233-239, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, VanDusen H, et al: Randomized trial of an inpatient palliative care intervention in patients hospitalized for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT). J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr 10004) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell DA, Shellens R, Roman E, et al. : Haematological malignancy: Are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliat Med 25:630-641, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Casarett DJ: What is different about patients with hematologic malignancies? A retrospective cohort study of cancer patients referred to a hospice research network. J Pain Symptom Manage 49:505-512, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron NB, et al. : Barriers to quality end-of-life care for patients with blood cancers. J Clin Oncol 34:3126-3132, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Temel JS, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, et al. : Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 31:710-715, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. : Code status documentation in the outpatient electronic medical records of patients with metastatic cancer. J Gen Intern Med 25:150-153, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffield P, Podzamsky JE: The completion of advance directives in primary care. J Fam Pract 42:378-384, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roeland EJ, Triplett DP, Matsuno RK, et al. : Patterns of palliative care consultation among elderly patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 14:439-445, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]