Abstract

In the intense, cure-oriented setting of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), delivery of high-quality palliative and end-of-life care is a unique challenge. Although HSCT affords patients a chance for cure, it carries a significant risk of morbidity and mortality. During HSCT, patients usually experience high symptom burden and a significant decrease in quality of life that can persist for long periods. When morbidity is high and the chance of cure remote, the tendency after HSCT is to continue intensive medical interventions with curative intent. The nature of the complications and overall condition of some patients may render survival an unrealistic goal and, as such, continuation of artificial life-sustaining measures in these patients may prolong suffering and preclude patient and family preparation for end of life. Palliative care focuses on the well-being of patients with life-threatening conditions and their families, irrespective of the goals of care or anticipated outcome. Although not inherently at odds with HSCT, palliative care historically has been rarely offered to HSCT recipients. Recent evidence suggests that HSCT recipients would benefit from collaborative efforts between HSCT and palliative care services, particularly when initiated early in the transplantation course. We review palliative and end-of-life care in HSCT and present models for integrating palliative care into HSCT care. With open communication, respect for roles, and a spirit of collaboration, HSCT and palliative care can effectively join forces to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary care for these highly vulnerable patients and their families.

INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) offers a curative option for some patients with high-risk malignancies and other life-threatening conditions. Although outcomes are improving,1 this opportunity for cure continues to involve intensive, prolonged therapy and confers a significant risk of morbidity and mortality. Patients who undergo HSCT can expect burdensome symptoms; a decrease in quality of life during the treatment2,3; and for a period thereafter, a risk for toxicity and/or death. For patients who proceed with allogeneic HSCT and do not survive, death often is a result of HSCT toxicity or complications, such as organ failure, graft-versus-host disease, and infection.1 Death usually follows a period of prolonged treatment and frequently occurs in the context of intensive cure-oriented care.4,5 Hematologic malignancy and HSCT physicians have ascribed this to sudden, rapidly changing, and unpredictable illness trajectories; a strong focus on cure; a reluctance to forego curative or restorative care; and availability of additional potentially curative treatments.6

The impact of these intensive end-of-life care patterns is significant, with HSCT recipients at high risk for suffering.7,8 Patients often lack the opportunity to prepare for end of life9 and cannot choose their preferred location of death. End-of-life care in the home setting usually is not feasible at this juncture, and hospice care is unlikely in this scenario.

By collaborating with HSCT clinicians, palliative care teams can play an important longitudinal role in helping HSCT recipients to live as well as possible throughout the transplantation trajectory through symptom management, supportive goal-concordant care, care coordination, and planning. For patients who survive and experience graft-versus-host disease or other long-term or late effects, palliative care can continue to play an active role in supporting well-being. For those who do not survive, palliative care can play an active role in ameliorating suffering, identifying priorities, and ensuring goal-concordant care at end of life.

PATTERNS OF END-OF-LIFE CARE AND THE NATURE OF HSCT

To understand how such collaboration can improve end-of-life care, the factors that underlie patterns of end-of-life care in HSCT are helpful to consider. HSCT is characterized by a strong focus on cure and survival. The primary goal is to cure the underlying condition that would otherwise prove fatal, even when the cost is high. When HSCT complications occur, a strong desire to reverse these iatrogenic conditions tends to exist. This cure-oriented focus both extends the lengths to which we might go to prolong life and supplants attention to other important outcomes, such as symptom control and preparation for end of life.

In a study of children whose last cancer-directed treatment was HSCT, 31% of physicians reported that the primary treatment goal at the time of death was cure/life extension; in contrast, for children whose last cancer-directed therapy was not HSCT, only 5% of physicians reported cure/life extension to be the primary treatment goal at the time of death.7 A goal of cure/life extension that persists to end of life may explain why HSCT recipients as well as the overlapping population of patients with hematologic malignancy receive more-intense care, with later resuscitation status discussions, more frequent deaths in the intensive care unit (ICU), and less opportunity for location of death to be planned or for hospice enrollment.5,7,10-15

Another key factor in HSCT end-of-life care patterns is that prognostication is particularly complex. Relapse after HSCT is complicated by the use of a second unplanned treatment and new targeted therapies with unproven outcomes in this setting. For nonrelapse mortality, prognostication is also complex. The clinical course can shift suddenly and rapidly when toxicity or complications arise. In addition, although indicators of a poor outcome (transfer to ICU, mechanical ventilation, failure of more than two organ systems) exist,16,17 the dying point often is difficult to discern,18 with recognition that the patient will not survive occurring late in the transplantation trajectory.6

The inability to communicate prognosis in a timely manner has important implications that lead to intense care and a high risk for suffering in HSCT recipients at end of life.7 Perception of impaired patient quality of life at end of life as well as late recognition of impending death have been associated with worse post-traumatic grief and depression outcomes in bereaved caregivers.19-21 Compared with the general oncology population, bereaved parents of pediatric HSCT recipients have a higher incidence of traumatic grief22 and higher rates of depression, stress, and anxiety.20,22

PALLIATIVE CARE AND HSCT

Evidence for the benefit of early palliative care in oncology23 has led to a call for enhanced palliative care services to begin early in the disease trajectory for high-risk patients.24 Given this recommendation and the high-risk nature and complexity of HSCT, patients who undergo HSCT could benefit from integrated palliative care. However, several factors prevail that can prevent palliative care integration in practice. As has been demonstrated in hematologic oncology, which crosses over with and is similar to HSCT, oncologists are less likely to consult palliative care for their patients9,25 and have negative perceptions of palliative care teams and involvement.10,26 A perception exists that HSCT and palliative care are mutually exclusive wherein palliative care teams are seen as death squads with no place in the cure-oriented realm of HSCT.26,27 Furthermore, some HSCT providers may believe that patients and families suspend their desire for quality of life during HSCT and that no intervention could improve the expected symptom burden and decline in quality of life after HSCT. However, recent evidence has shown that patients and families prioritize quality of life even while pursuing intense curative therapy.28 In addition, evidence supports successful integration of palliative care with HSCT29-31 and, contrary to previous notions, that early palliative care integration in HSCT leads to improved patient and caregiver outcomes.32 Although HSCT presents a particularly complex challenge in establishing integrated palliative care services, the unique challenges also present opportunities to develop novel models of care and partnerships with other disciplines to address these needs. Next, we present models of palliative care integration as well as considerations for their broad application.

MODELS OF INTEGRATION

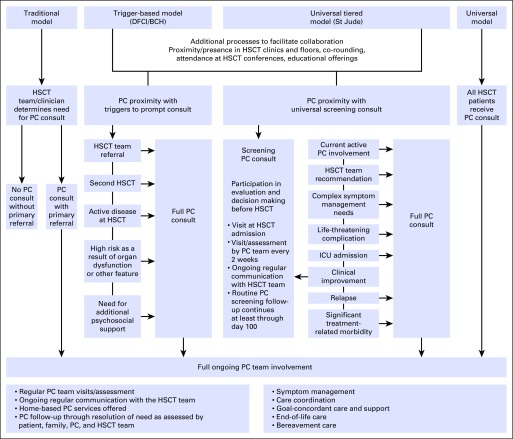

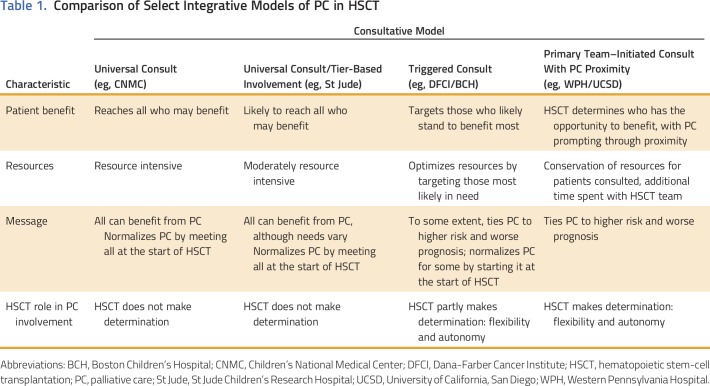

Multiple models of palliative care integration in oncology have been proposed that range from oncologist-delivered primary palliative care with referral for specialty palliative care in a consultative model, to systems-based trigger-prompted involvement, to embedded and fully integrated models of care.29-31,33,34 With consideration of diversity in oncology practice and across disparate settings, no one model exists as a paradigm for all. We discuss a few models of palliative care integration in HSCT for various clinical settings, including novel models implemented at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St Jude) and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital (DFCI/BCH; Fig 1) and models previously described at Children’s National Medical Center (CNMC)30; the University of California, San Diego31; and Western Pennsylvania Hospital29 (Table 1).

Fig 1.

Schematic of select models of palliative care (PC) integration in hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT). BCH, Boston Children’s Hospital; DFCI, Dana-Faber Cancer Institute; ICU, intensive care unit; St Jude, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Table 1.

Comparison of Select Integrative Models of PC in HSCT

A primary oncologist–driven, consult-based model with palliative care provider proximity for integration of palliative care in HSCT, as used at Western Pennsylvania Hospital and the University of California, San Diego, is characterized by the physical presence of the palliative care team at weekly team meetings and daily on the units.29,31 Such proximity can lead to successful integration with education, relationship building, and collaboration as well as to prompt identification of patients on the HSCT service who may benefit from palliative care services. This model augments a traditional consultative model by fostering collaboration between services, but because consultation is at the discretion of the primary team, this model carries the risk of missing some patients who could benefit from a palliative care consult and have not been referred. Furthermore, palliative care consultation typically occurs after the start of HSCT, often when already complex symptoms or complications exist. The DFCI/BCH model combines this approach with a systems-based trigger that prompts primary HSCT teams to initiate a palliative care consult when the trigger conditions are met. This model not only maintains primary HSCT team control in consultation but also, with collaborative efforts, provides guidelines for when palliative care consultation may be of benefit.

The St Jude model of palliative care integration offers near-universal consultation in HSCT at a basic level with triggers for escalating levels of involvement, which effectively delivers individualized titrated palliative care services to patients. In this way, the palliative care team aims to reach the majority of HSCT patients early in their course of treatment but reserves full team resources for those who would benefit most. A fully integrated model in which palliative care consultation is embedded in HSCT and provides full consultative services to all patients is one that has great potential benefits but would require significant dedicated resources. A pilot study in all HSCT patients at CNMC found that palliative care consultation was feasible and received positively by families and clinicians alike but was noted to be time intensive30 and likely to require additional palliative care consultants.

For preemptively integrated models, the initial consult occurs before the start of transplantation, usually before admission. The aim of the initial consult is to introduce the service and learn about the goals, values, hopes, and fears of each individual patient and family. Through these means, the team begins to establish a relationship with the patient and family that can guide individualized care planning and coordination.35 Throughout the transplantation course, palliative care interventions include symptom assessment and recommendations, goal-directed supportive care, team collaboration, and care coordination. Additional in-depth analysis of the novel models of integration described here will help to highlight the benefits and challenges of integrative model implementation.

The clinical palliative care service at St Jude began as a full-scale consultative service in 2008. The HSCT service accounted for a small percentage of referred patients in the early years of the program, but the number of referrals tripled by year 5.33 By 2015, the HSCT service recognized the potential benefit of the broad application of early palliative care integration, and after careful planning, an integrated systems-based model36 of palliative care in HSCT was implemented in 2016.

The St Jude integrated model includes initial screening consultation during the pre-evaluation period for every patient planned to undergo allogeneic HSCT. This consult is structured as a 30-minute targeted encounter with, at a minimum, a physician and nurse practitioner and involves an exploration of the patient’s and family’s values, goals, hopes, and fears through a series of five prompts: Tell us about yourself. What is a good day for you? What are you hoping for? What are you worried about? How do you define a good parent?37 The palliative care team then follows each patient weekly from admission for HSCT through inpatient discharge and then every 2 to 3 weeks until at least day 100. Triggers for increased levels of involvement include development of refractory symptoms, life-threatening complications, ICU admission, or team recommendation (Fig 1).

The integration of palliative care in HSCT at St Jude has enabled earlier identification of patients who may benefit from palliative care services as well as facilitated palliative care service delivery. The potential benefit has not been limited to individual patient management because integration in the team has led to universal practice changes, such as incorporation of a novel antiemetic regimen into standard HSCT practice. Although the service has had to respond to increased consultative needs, staffing has not been affected because of the controlled nature of consultation and positive downstream effects.

The pediatric palliative care program at DFCI/BCH, the oldest continuously running program in the United States that has been serving children with advanced illness since 1997,38 implemented an integrated palliative care consultation model in HSCT in 2009. In this model, children who meet any of the following criteria are referred to palliative care: second planned HSCT, evidence of active disease at the time of HSCT, significant organ impairment or other high-risk feature, anticipated need for significant psychosocial support, or perceived need for an additional layer of support for themselves or their family as deemed by the HSCT clinician (Fig 1). These criteria and the presence of a palliative care faculty member at intake meetings prompt HSCT clinicians to consider palliative care consultation by identifying patients and families who would be most in need of support allowing for flexibility.

A recent comparison of children who underwent HSCT at DFCI/BCH who did and did not receive palliative care suggests that palliative care involvement affects some end-of-life outcomes.4 Children with palliative care involvement had earlier communication about prognosis and resuscitation status as well as less-intensive treatment at end of life, including fewer deaths in the ICU, fewer intubations, and no cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Few patients died at home or with hospice services, irrespective of palliative care involvement. Among those who received palliative care, a trend toward greater hospice use with longer palliative care involvement (> 1 week) was observed, which suggests that earlier involvement of palliative care concurrent with HSCT care affords more opportunity for planning for end of life.

SOME CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INTEGRATING PALLIATIVE CARE

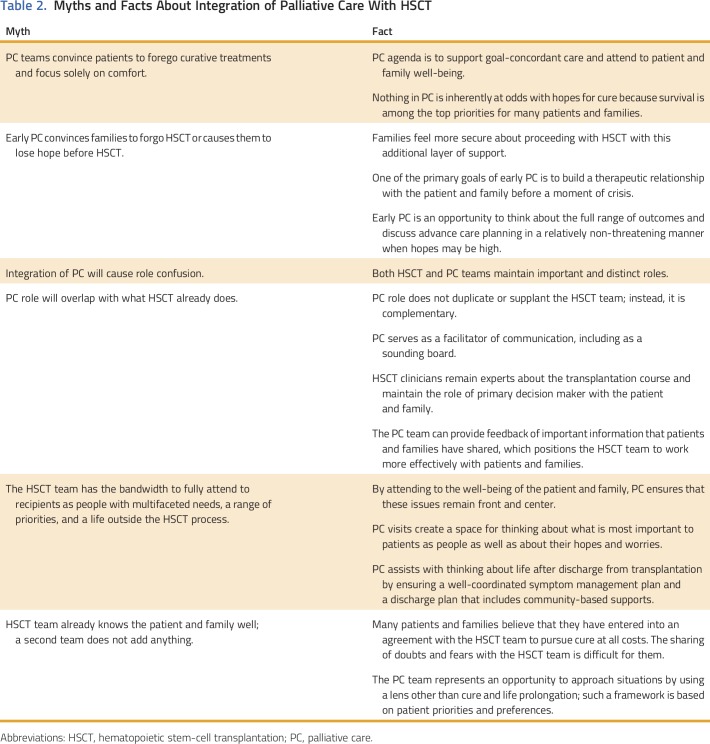

Table 2 lists important considerations in the development of an integrated palliative care program. First, a misconception exists that that involvement of palliative care convinces families to forgo HSCT. Palliative care approaches families with no agenda other than to offer support. In addition, many patients and families who consider HSCT do not consider the procession to transplantation to be an actual decision.39 For example, at DFCI/BCH, only three of 244 initial palliative care consultations included a discussion of the HSCT decision-making process, and of these patients and families, all proceeded to HSCT. In fact, families may feel more secure about proceeding with HSCT with palliative care as an additional layer of support in place.

Table 2.

Myths and Facts About Integration of Palliative Care With HSCT

Second, early and universal involvement of palliative care before the start of HSCT reinforces the message that palliative care should not be equated with end of life or a poor prognosis, which in turn obviates the reluctance to engage with palliative care that this notion fosters. Furthermore, the ability to begin to build a therapeutic alliance with the patient and family before a moment of crisis is invaluable. Early involvement of palliative care is especially important for patients who experience significant morbidity after HSCT and for those who are approaching end of life. In such instances, the palliative care team can build upon this relationship and is better positioned to aid with complex symptom management, decision-making support, advance care planning, and anticipatory bereavement.

Third, the HSCT and palliative care teams should each maintain important and distinct roles. Palliative care should not duplicate or supplant the role of the HSCT team; rather, it should play a complementary role, with HSCT remaining the primary team and maintaining the role of primary decision maker with the patient and family. The palliative care team often takes on a crucial role as facilitator of communication by processing information provided by the HSCT team, serving as a sounding board for patient and family thoughts, and creating a space for thinking about what is most important to the patient and family and what brings them joy and strength in the midst of a trying time. The HSCT team, which is focused on the important task of attending to the patient’s medical needs, may not have the time or so-called bandwidth to take up these issues. Instead, with permission, the palliative care team can provide important feedback that patients and families have shared.

Additional considerations include other key palliative care functions. A primary palliative care role is attendance to the well-being of the patient and family, and palliative care involvement helps to ensure that this issue remains front and center in the midst of this intense, cure-oriented setting. Fulfillment of this role involves meticulous symptom management, which sometimes involves thinking outside the box, and consideration of nonpharmacologic approaches that might not have otherwise been considered. The palliative care team also should collaborate with HSCT psychosocial clinicians to support patient and family coping during this challenging and high-stakes time. Palliative care teams are frequently involved in discharge planning and coordination of care by helping families to think about life after discharge from the HSCT unit, ensuring a well-coordinated symptom management plan, and creating a discharge plan that includes community-based supports. By attending to these issues, particularly those related to end-of-life care, the palliative care team can also attend to staff moral distress, which is common in HSCT,40 and may be a mechanism to alleviate work-related stress and burnout.41

Another critical role of the palliative care team is to provide a space in which patients and families can share their hopes, worries, and doubts. Many believe that they have entered into an agreement with the HSCT team to pursue cure at all cost, and they experience pressure, however unintended, to maintain a positive outlook.42 Sometimes, patients and families find it difficult to share their worries or doubts with the HSCT team, but the palliative care team represents an opportunity to voice their concerns and share what is most important to them through a different framework while still maintaining hope. This role is especially important when the patient has life-threatening complications, when the chance for cure is waning, and as the patient approaches end of life.

Finally, the palliative care team can provide much-needed bereavement support for the families of HSCT patients who do not survive. This critical role has great potential benefit given that caregivers of HSCT recipients have been shown to have worse bereavement outcomes with higher rates of traumatic grief, depression, stress, and anxiety.20,22 Early palliative care team involvement can enhance support for patients and families throughout the HSCT course, including preemptive anticipatory bereavement and comprehensive bereavement follow-up.

WHICH MODEL?

The model that works best in any given setting depends on multiple factors, including the size and scope of the HSCT and palliative care programs, the resources available, and the institutional culture. The critical first step to any clinical partnership is support from the leadership of each division or department. A successful collaboration between HSCT and palliative care begins with establishing mutual respect, delineating roles and responsibilities, and having a willingness to learn from each other. Staff from both HSCT and palliative care should receive education in the other field to enrich perspectives and clinical expertise in context. Integration of the palliative care and HCST services can also be more seamless when the palliative care faculty maintains a presence at HSCT divisional meetings, educational lectures, and clinical conferences. A cooperative needs assessment can aid in determining which model of collaboration best fits each unique setting.

In developing new HSCT palliative care collaborations, the unique features of HSCT that once rendered this type of partnership unlikely are important to keep in mind. HSCT remains a culture of intense curative and restorative therapy where palliative care delivered concurrently can be elusive. Of note, incorporation of palliative care in HSCT does not change the focus of therapy or detract from the goal to cure and restore. In fact, patients with serious illness and their families often hold concurrent goals of cure and quality of life and maintain both hopes for restoration or cure alongside hopes to live as well as possible.43,44 Furthermore, HSCT patients experience a high burden of physical and emotional symptom suffering,2,3 and patient and caregiver outcomes can be improved with early palliative care involvement.32 A reframing in this way reveals that palliative care and HSCT are not mutually exclusive but, rather, are ideally suited for a clinical partnership to offer optimal comprehensive care for HSCT patients and families.

In conclusion, the practice of reserving palliative care for end of life is a key impediment to timely palliative care consultation, especially in HSCT where identification of the end-of-life phase is especially challenging. This intense, high-stakes setting, fraught with uncertainty, is where patients and families should receive extraordinary HSCT and palliative care. The model of palliative care integration may vary across care settings, yet all models have a common goal of improving quality care for patients throughout the HSCT trajectory through clinical partnership. Promotion of a culture that embraces concurrent palliative care and HSCT could ensure comprehensive quality care for HSCT patients and their families.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (to D.R.L.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant 1K23HL107452 (to C.U.), and Gloria Spivak Faculty Career Development Fund (to C.U.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Administrative support: Leslie E. Lehmann

Provision of study materials or patients: Leslie E. Lehmann

Collection and assembly of data: Deena R. Levine, Christina Ullrich

Data analysis and interpretation: Deena R. Levine, Christina Ullrich

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Strange Bedfellows No More: How Integrated Stem-Cell Transplantation and Palliative Care Programs Can Together Improve End-of-Life Care

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Deena R. Levine

No relationship to disclose

Justin N. Baker

No relationship to disclose

Joanne Wolfe

No relationship to disclose

Leslie E. Lehmann

No relationship to disclose

Christina Ullrich

Consulting or Advisory Role: Schulman IRB

REFERENCES

- 1. D'Souza A, Zhu X: Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT): CIBMTR summary slides, 2016. http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 2.Roeland E, Mitchell W, Elia G, et al. Symptom control in stem cell transplantation: A multidisciplinary palliative care team approach. Part 1: Physical symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:100–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roeland E, Mitchell W, Elia G, et al. Symptom control in stem cell transplantation: A multidisciplinary palliative care team approach. Part 2: Psychosocial concerns. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullrich CK, Lehmann L, London WB, et al. End-of-life care patterns associated with pediatric palliative care among children who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D, Didwaniya N, Vidal M, et al. Quality of end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2014;120:1572–1578. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odejide OO, Salas Coronado DY, Watts CD, et al. End-of-life care for blood cancers: A series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e396–e403. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ullrich CK, Dussel V, Hilden JM, et al. End-of-life experience of children undergoing stem cell transplantation for malignancy: Parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. Blood. 2010;115:3879–3885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Button EB, Gavin NC, Keogh SJ. Exploring palliative care provision for recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation who relapsed. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:370–381. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.370-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, et al. Differences in end-of-life communication for children with advanced cancer who were referred to a palliative care team. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1409–1413. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Casarett DJ. What is different about patients with hematologic malignancies? A retrospective cohort study of cancer patients referred to a hospice research network. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, et al. Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: Impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108:djv280. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock KE, Steineck A, Twist CJ. Trends in end-of-life care in pediatric hematology, oncology, and stem cell transplant patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:516–522. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jalmsell L, Forslund M, Hansson MG, et al. Transition to noncurative end-of-life care in paediatric oncology—A nationwide follow-up in Sweden. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:744–748. doi: 10.1111/apa.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, et al. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: Independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3184–3189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brück P, Pierzchlewska M, Kaluzna-Oleksy M, et al. Dying of hematologic patients—Treatment characteristics in a German university hospital. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2895–2902. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saillard C, Blaise D, Mokart D. Critically ill allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients in the intensive care unit: Reappraisal of actual prognosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1050–1061. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balit CR, Horan R, Dorofaeff T, et al. Pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant and intensive care: Have things changed? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:e109–e116. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Docherty SL, Miles MS, Brandon D. Searching for “the dying point”: Providers’ experiences with palliative care in pediatric acute care. Pediatr Nurs. 2007;33:335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surkan PJ, Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, et al. Perceptions of inadequate health care and feelings of guilt in parents after the death of a child to a malignancy: A population-based long-term follow-up. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:317–331. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalmsell L, Onelöv E, Steineck G, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with cancer and the risk of long-term psychological morbidity in the bereaved parents. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy MC, Clarke NE, Ting CL, et al. Prevalence and predictors of parental grief and depression after the death of a child from cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1321–1326. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drew D, Goodenough B, Maurice L, et al. Parental grieving after a child dies from cancer: Is stress from stem cell transplant a factor? Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11:266–273. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.6.18293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al. Health care utilization and end-of-life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2015;121:2840–2848. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morikawa M, Shirai Y, Ochiai R, et al. Barriers to the collaboration between hematologists and palliative care teams on relapse or refractory leukemia and malignant lymphoma patients’ care: A qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:977–984. doi: 10.1177/1049909115611081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung HM, Lyckholm LJ, Smith TJ. Palliative care in BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:265–273. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, et al. Patients’ and parents’ needs, attitudes, and perceptions about early palliative care integration in pediatric oncology. JAMA Oncol. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0368. [epub ahead of print on March 9, 2017] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selvaggi KJ, Vick JB, Jessell SA, et al. Bridging the gap: A palliative care consultation service in a hematological malignancy-bone marrow transplant unit. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12:50–55. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafond DA, Kelly KP, Hinds PS, et al. Establishing feasibility of early palliative care consultation in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2015;32:265–277. doi: 10.1177/1043454214563411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roeland E, Ku G. Spanning the canyon between stem cell transplantation and palliative care. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:484–489. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2094–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine DR, Johnson LM, Snyder A, et al. Integrating palliative care in pediatric oncology: Evidence for an evolving paradigm for comprehensive cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:741–748. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:89–98. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker JN, Barfield R, Hinds PS, et al. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: The individualized care planning and coordination model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaye EC, Friebert S, Baker JN. Early integration of palliative care for children with high-risk cancer and their families. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:593–597. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5979–5985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duncan J, Spengler E, Wolfe J. Providing pediatric palliative care: PACT in action. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32:279–287. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000287997.97931.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pentz RD, Pelletier W, Alderfer MA, et al. Shared decision-making in pediatric allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation: What if there is no decision to make? Oncologist. 2012;17:881–885. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly D, Ross S, Gray B, et al. Death, dying and emotional labour: Problematic dimensions of the bone marrow transplant nursing role? J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:952–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallagher R, Gormley DK. Perceptions of stress, burnout, and support systems in pediatric bone marrow transplantation nursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:681–685. doi: 10.1188/09.CJON.681-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrath P. Are we making progress? Not in haematology! Omega (Westport) 2002;45:331–348. doi: 10.2190/KU5Q-LL8M-FPPA-LT3W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: Impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinze KE, Nolan MT. Parental decision making for children with cancer at the end of life: A meta-ethnography. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29:337–345. doi: 10.1177/1043454212456905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]