Abstract

PEGylation, the attachment of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), has been adopted to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of oligonucleotide therapeutics for nearly 30 years. Prior efforts mainly focused on the investigation of linear or slightly branched PEG having different molecular weights, terminal functional groups, and possible oligonucleotide sites for functionalization. Recent studies on highly branched PEG (including brush, star, and micellar structures) indicate superior properties in several areas including cellular uptake, gene regulation efficacy, reduction of side effects, and biodistribution. This review focuses on comparing the effects of PEG architecture on the physiochemical and biological properties of the PEGylated oligonucleotide.

Keywords: PEGylation, oligonucleotide, brush polymer, antisense, small interfering RNA, aptamer, phosphorothioate

1. Introduction

Oligonucleotides (ONs), which are short DNA or RNA sequences (typically 15–30 mer), are considered a new class of “informational” therapeutics [1–3]. Unlike traditional small-molecule drugs, in which a change in the chemical structure is inevitably associated with a change in the pharmacokinetic properties, ON-based drugs have drug-like properties by and large independent from the information they carry, which is written into the base sequence. Thus, once an optimized ON formulation is developed for efficient and safe delivery to a specific organ or tissue, a variety of disease targets within the tissue can be addressed simply by changing the sequences of the ONs. This fundamental advantage over small-molecule drugs, combined with rapid advances in molecular-level understanding of disease processes and gene sequencing, promises extremely fast drug development cycles and reduced developmental cost, and can potentially enable personalized treatment at the individual level [4–7].

Despite intense research, the rate of output of ON-based drugs is not nearly as fast as originally anticipated, with only six drugs reaching the market over the last two decades [8]. The slow bench-to-bedside translation reflects the difficulties associated with ON drugs [9, 10]. Unmodified, naked ONs are easily degraded by nucleases, can undergo rapid renal and hepatic clearance, and are hopelessly incapable of cellular entry owing to a combination of hydrophilicity and high molecular weight (MW) [11, 12]. Solutions to these challenges include the use of advanced delivery systems (e.g., polycationic polymers, nanoparticles, or liposomal formulations [13–16]) and direct chemical modification of the ON [17]. Other than liposomes, most carrier systems still need to be proven relevant in a clinical setting [18]. Challenges include toxicity, immunogenicity, consistency in formulation (especially for complex systems with multiple components), chemical and in vivo stability, release control, and problems associated with large-scale manufacturing. Direct chemical modification of the ON is a more successful approach. The first chemical modification applied to ONs remains the most commonly used: the phosphorothioate backbone [19]. This modification increases enzymatic stability of the ON and improves its cellular uptake [20]. Moreover, phosphorothioate allows ONs to associate with plasma proteins, preventing them from rapid renal clearance [21]. Other modifications, predominantly 2′-modifications and conformation prearrangements, increase stability and binding affinity but are effective only when used with phosphorothioates [22]. Chemical modifications are not without drawbacks. For example, phosphorothioates reduce the binding affinity of the ON for its target, sometimes necessitating other modifications to compensate [23]. In addition, phosphorothioates are associated with nonspecific adverse effects including induction of stress responses, prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), thrombocytopenia, and increased serum transaminase activities [24–26]. Therefore, new modifications or strategies to replace or reduce the use of phosphorothioates are still sought after.

ONs may interact with biological systems through a multitude of mechanisms; therefore, several classes of ONs are being explored as therapeutics, including antisense ONs, splice-correcting ONs, small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and aptamers [27–30]. Antisense ONs are called “antisense” because the ON base sequence is complementary to the messenger RNA (mRNA) within the cell, which is called the “sense” sequence. The hybridization of the antisense ON with the mRNA inactivates it by either physically blocking the translation process or by activating RNase H, which cleaves the mRNA at the RNA–DNA duplex, effectively turning off a target gene [31]. Alternatively, the antisense ON can be designed to bind to a splicing site on a pre-mRNA, allowing exon content in the mature mRNA to be modified. The first antisense drug, fomiversen, was approved in 1998 for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients via intraocular injections, but has been discontinued due to poor demand [32, 33]. In 2013, the first systemically administered ON drug, mipomersen, was approved in USA for treating homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Mipomersen is an antisense ON with a full phosphorothioate backbone, which works by controlling the expression of apolipoprotein B-100 (produced in the liver) [34]. Nevertheless, it was rejected by the European Medicines Agency owing to concerns about liver and cardiovascular toxicity [35]. Nonetheless, mipomersen injected greater interest in the development of ON drugs. Two new antisense drugs, nusinersen and eteplirsen, were approved in USA in 2016 for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, respectively [36, 37]. Both drugs are phosphorothioate-modified antisense ONs that edit the exon content of disease-related mRNAs via splice manipulation. Currently, antisense drugs still dominate clinical development, although significant interest is shifting toward RNA interference (RNAi) [8, 33].

RNAi is the biological process in which oligomeric RNA molecules (typically double-stranded) regulate the expression of genes by inhibiting or selectively cleaving the target mRNA [38]. Through a series of processing steps, the “guide” strand of the siRNA separates from the complementary “passenger” strand and is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which can then recognize target mRNA via base pairing with the guide strand. Critical for the RISC is an Argonaute protein, which serves as the catalytic component that can cleave many copies of the target mRNA. RNAi is thought to be more efficient and robust than antisense technology for gene suppression [39]. On the other hand, given the more complex biological processing, siRNA tolerates fewer chemical modifications, and advanced delivery platforms such as lipid nanoparticles are often employed for improved stability and pharmacokinetics [40]. Although as of January 2018, no siRNA-based formulation has received regulatory approval, meaningful clinical productivity is approaching. Patisiran, a lipid particle-formulated siRNA targeting transthyretin for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and is set to become the long-awaited breakthrough in siRNA therapeutics [41, 42]. A number of GalNAc-modified siRNA candidates are following closely in late-stage clinical trials [43].

MiRNAs are a closely related class of ONs involved in gene regulation [44]. MiRNAs play several roles in normal cellular functions as well as initiation and progression of diseases, such as cancers and cardiovascular disease [45]. Although the majority of miRNAs are intracellular, some are found in the circulation system (termed circulating miRNAs), which are important biomarkers [46]. Mechanisms of therapeutic action include supplying depleted miRNA or antagonizing upregulated miRNA, among others. On the translational scene, a mimic of the tumor suppressor miR-34 reached phase I clinical trial for cancer but was terminated due to immune-system-related adverse events [47]. An anti-miR targeting miR-122 for hepatitis treatment underwent a phase II trial with successful results [48].

Aptamers are a unique class of ONs with secondary structure that recognizes endogenous molecules (similar to antibodies) and are thus not limited to base pairing with a complementary strand [49]. As such, aptamer drugs may function extracellularly, unlike antisense ONs or siRNAs. Pegaptanib, which was approved in 2004 for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration, remains the only aptamer drug on the market [50]. Being a PEGylated aptamer, pegaptanib binds to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as an antagonist and blocks ocular angiogenesis, a major pathological process responsible for vision loss.

Pegaptanib set a precedence for PEGylation of ON drugs to improve their biopharmaceutical properties. PEGylation refers to covalent attachment of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) [51]. PEG contains a highly flexible, noncharged, and hydrophilic backbone, with only terminal sites available for functionalization. It has been used to improve the biopharmaceutical properties of protein drugs since the 1990s, and over a dozen PEGylated pharmaceuticals are currently on the market [52]. PEG creates a large hydration shell, which sterically blocks other biomacromolecules from penetrating through the polymer layer and binding with the interior substrate [53, 54]. Binding requires displacing the PEG by the incoming molecule, generally making such binding less thermodynamically favorable. These properties usually result in weaker interactions between the receptor and the conjugated molecule, but increased drug solubility, prolonged blood circulation, and increased drug stability often offset by the reduced binding affinity. Of note, PEGylated ONs can be an exception to this generalization, with increased binding to a complementary sequence compared to unmodified ONs. The effect is attributed to macromolecular volume exclusion (vide infra) [55]. Recently, Wurm et al. discovered that protein absorption is essential for the stealth effect of PEG, which challenges the previously accepted mechanism [56]. It has been shown that PEGylated nanoparticles absorb a large amount of clusterin proteins to form a protein corona, which prevents nonspecific cell uptake.

The way PEG shields its conjugated payload offers new challenges and opportunities for ON PEGylation. Other than aptamers, the target of most ONs is a complementary sequence, which is a slender molecule (cross-section diameter much smaller than that of proteins) that should experience significantly less steric hindrance entering the PEG hydration layer than proteins. Thus, it is possible to use higher densities of PEG to achieve a greater shielding effect against proteins and degrading enzymes without compromising ON target binding. This recognition has led to the development of a series of brush-, star-, and micelle-type ON conjugates, which increase the local density of PEG [57–63]. The multiarm PEG structure can be made large enough (~ 300 kDa, the size of a typical small nanoparticle or a large protein) to evade renal clearance and achieve relatively long blood circulation without the need for phosphorothioates. Therefore, with these higher-density PEG conjugates, it is possible to employ native phosphodiester ONs for therapeutic applications, bypassing the potential adverse effects associated with chemically modified ONs. In this review, we address the recent advances in PEGylated ONs with a focus on how the PEG architecture affects the physiochemical and biological properties of the ON.

2. PEGylation of ONs using linear or slightly branched PEG

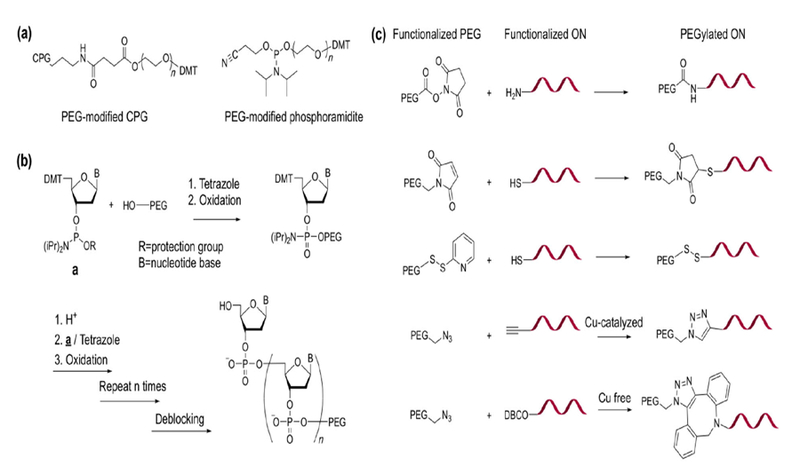

PEGylation of an ON using linear PEG was reported in the 1990s. Jäschke et al. have developed a suite of PEG-modified phosphoramidites and controlled pore glass (CPG) to incorporate PEG into 5′, 3′, or internal positions of ONs through automated DNA synthesis (Fig. 1(a)) [64, 65]. A large library of PEGylated ONs with different PEG MW (400 Da to 4 kDa) and conjugation sites has been successfully prepared. Incorporation of PEG during the synthesis of an ON can achieve the best control over the number and location of PEG conjugation instances. Nonetheless, due to the limited pore size of the CPG and high viscosity of PEG acetonitrile solutions (a high concentration, ~ 0.15 M, is needed for solid-phase coupling) [66], PEG MW is limited, and the PEGylation yield decreases with increasing MW. To obtain higher-MW PEG conjugates, Bonora et al. have developed a solution synthesis method termed high-efficiency liquid-phase (HELP) synthesis, which uses hydroxyl-terminated PEG as a soluble polymer support, onto which phosphoramidites are sequentially added (Fig. 1(b)) [67]. PEGylated ONs with high-MW PEG (5–20 kDa) have been successfully prepared at a medium scale (~ 100 mg) [68]. The HELP synthesis requires precipitation to remove unreacted phosphoramidites and other residues at each synthetic step, making it labor intensive. Livingston et al. later improved the liquid-phase synthesis by developing an organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) strategy, which involves a membrane process capable of separating growing PEG-ONs from small-molecule residues [69–71]. The OSN method has the potential to be automated for very large-scale synthesis (possibly > 100 kg, although not yet attempted). These types of liquid-phase ON synthesis, while ensuring that each product molecule contains a PEG chain, make it difficult if not impossible to purify failed ONs with missing nucleotides because of the high-MW PEG attached.

Figure 1.

Chemical synthesis of PEGylated ONs. (a) Structures of PEG-modified CPG and phosphoramidite. (b) HELP synthesis of PEGylated ON. (c) Commonly used chemical reactions for PEG-ON conjugation.

The more widely adopted method of synthesizing PEGylated ONs involves different conjugation chemistries after ON synthesis (Fig. 1(c)). In these cases, PEG and ONs are separately functionalized with different reactive groups, which can couple with each other to form covalent bonds. A variety of conjugation reactions, including Michael addition, disulfide exchange, amidation chemistries, and copper-catalyzed and copper-free click chemistries for ON PEGylation have been reported [72, 73]. These reactions can be carried out in either the liquid or the solid phase. For liquid-phase coupling, pre-purified ONs can be used, which ensures that all conjugates have the correct ON sequence. Successfully PEGylated ONs can be purified from unreacted ON and PEG by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) due to increased hydrophobicity relative to free ON, thus resulting in extended elution time. Gel electrophoresis and ion exchange chromatography are also utilized to purify PEGylated ONs on the basis of changes in size and charge density [74]. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) is rarely conducted to purify linear PEG-ON conjugates, owing to the limited size increase after PEGylation. Solid-phase coupling of PEG to CPG-supported ONs simplifies the purification by ensuring that there is no unreacted PEG, and also produces conjugates with the correct ON sequence (failed strands are capped during synthesis and therefore cannot be PEGylated) [75]. Nevertheless, as is the case for PEG phosphoramidites, the PEG MW is a limiting factor for solid-phase synthesis, and the synthesis is generally limited to small-to-medium scale. Another possibility to create PEGylated ONs involves enzymatic ligation (e.g., with T4 DNA ligase) to link together a pre-PEGylated double-stranded DNA (donor) with a second double-stranded DNA (acceptor) [76]. This modularized approach has the potential to create a large number of PEG conjugates without needing to perform PEG-ON conjugation and purification each time, thus reducing synthetic cost. Nevertheless, it necessitates extra ON length in the final conjugate owing to the use of the donor sequence, which may reduce the effectiveness of the PEG.

In terms of PEGylation regiochemistry, 5′ and 3′ termini of the ON are the predominant sites for conjugation. It has been recognized that 3′ modifications result in more enzymatically stable conjugates (~ 2–3-fold increase of enzymatic half-life in plasma), because 3′-exonucleases account for the majority of exonucleolytic activity [77, 78]. For siRNA, PEGylation at the 5′ of the guide strand should be avoided because the 5′ end is involved in phosphorylation and interaction with the Argonaute component of the RISC [79]. In contrast, Park et al. have PEGylated double-stranded siRNA at all possible termini (5′ sense/antisense or 3′ sense/antisense), and discovered that gene silencing activity was not affected by the conjugation site [80]. Similarly, Winkler et al. have also reported nearly identical knockdown efficacies using two PEGylated antisense strands at either 5′ or 3′ [81]. Internal positions (often via 2′-O) are also used. Nonetheless, 2′ PEGylation usually involves a very short PEG or even a single methoxyl ethyl (MOE) group, which is incorporated to the nucleotide prior to ON synthesis [82]. Internal positions can also be PEGylated after ON synthesis using modified bases, such as the dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-functionalized thymine (T) base, which reacts with azide-modified PEG. Postconjugation is amenable to high-MW linear PEG and highly branched PEG [62].

Regarding whether PEGylation stabilizes or destabilizes ON hybridization, opposing data exist in the literature. For example, Deiters et al. have shown that the melting temperature (Tm) of an antisense ON modified with 5, 20, or 40 kDa PEG decreased sharply by 6, 13, or 19 °C as compared with unmodified control [83]. Winkler et al. have also reported that a 500 Da short PEG yielded a minor destabilizing effect (−1 °C in Tm) for a phosphodiester ON, but a minor stabilizing effect (+1 °C) for a full-phosphorothioate ON [81]. On the other hand, Kawaguchi et al. have observed that a Y-shaped 10 kDa PEG increases the Tm of a phosphodiester ON by 2.4 °C [84]. Besides, Jäschke et al. have observed an increase of ~ 3 °C in Tm for mono- and bis-PEGylated ON with 1 kDa PEG [65]. Our group has systematically compared the hybridization thermodynamics of several PEG-ON conjugates involving linear (2, 5, 20, and 40 kDa) and Y-shaped (40 kDa) PEG by analyzing the thermal denaturation profiles of double-stranded DNA via the Van’t Hoff equation [59]. Our results suggest that PEGylation generally has a net stabilizing effect on a duplex ON, and the strength of the effect is dependent on the MW and the architecture of the PEG. The stabilizing effect is attributed to macromolecular volume exclusion, which increases the effective concentration of the ON, leading to more favorable binding [85]. The phenomenon is well documented for PEG-DNA cosolutions (usually observable at [PEG] > 50 g/L, and increases with PEG MW), but not for conjugates [86]. In a conjugate system, the volume exclusion effect is localized. Within the gyration radius of the conjugate, the weight% of PEG is constant, making the increased binding affinity concentration-independent (observable even when [conjugate] < 0.005 g/L). When the local PEG density is high, e.g., in brush-type PEG-ON conjugates, PEG begins to negatively affect hybridization, possibly by displacing water molecules that would otherwise stabilize the Watson–Crick base pairing. This destabilizing factor partially offsets the stabilizing volume exclusion effect, resulting in smaller net stabilization of the duplex. Of note, these effects are minor, causing a ~ 1–3 °C change in Tm; PEGylated ONs remain strong binders to target sequences despite the type and MW of PEG.

After systemic administration, unmodified ONs are rapidly cleared from the blood stream primarily via kidneys because MW is less than the renal filtration limit (~ 65 kDa), with distribution half-life in plasma (t1/2α) of several minutes (Table 1) [87–89]. PEGylation slightly improves t1/2α, which is, however, still generally < 1 h. The majority of injected ONs are quickly removed from blood circulation despite their PEGylation status or whether phosphorothioates are used [90]. PEGylation is known to prolong elimination half-life (t1/2β) to several hours [84, 91, 92]. For example, oblimersen, a full-phosphorothioate antisense strand targeting antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, shows t1/2α and t1/2β of 5 and 38 min, respectively, after intravenous injection in a mouse model [93]. After PEGylation with a linear 20 kDa PEG, t1/2β got extended to ~ 15 h [94]. Similarly, ARC122, a 40 kDa PEG-modified aptamer having 2′-fluorine- and 2′-O- MOE modifications, showed increased t1/2α and t1/2β of 0.6 and 11.7 h respectively from 0.4 and 4.9 h for the non-PEGylated version (ARC83). Despite the increased t1/2β, PEGylation does not significantly alter the biodistribution profile of these ONs, which primarily accumulate in the liver and kidneys because of low blood concentration after rapid initial distribution into tissues [95]. As such, PEGylated ONs are often more beneficial for local administration. McCauley et al. have studied a subconjunctivally injected PEGylated aptamer in rat and rabbit models. It was shown that the PEGylated aptamer with 20 and 40 kDa PEG had prolonged residential periods in the eye (tmax in plasma: 6 and 12 h, respectively), compared to non-PEGylated aptamer (tmax: 1 h). The increase in plasma tmax with increasing PEG MW suggests that PEG is responsible for the reduced diffusion into plasma [96]. Overall, linear can effectively prolong elimination half-life but is unlikely to significantly enhance ON blood circulation time and blood availability [97].

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic studies comparing free ONs and PEGylated ONs with linear or slightly branched PEG

| Oligonucleotide | PEG | T1/2α(h)a | T1/2β (h)a | Species | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO, aptamer | N/A | N/A | 0.15 | Rat | [89] |

| PS/2’-MOE, antisense (mipomerson) | N/A | 0.33 | N/A | Mouse | [88] |

| 0.39 | 4.7 | Rat | |||

| 0.68 | 16 | Monkey | |||

| 1.26 | 31.1 | Human | |||

| PO/2’-MOE, antisense (eteplirsen) | N/A | N/A | ~ 3–4 | Human | [37] |

| PS, antisense (oblimerson) | N/A | 0.08 | 0.63–0.80 | Mouse | [93] |

| Linear, 20 kDa | N/A | 15.0 | Mouse | [94] | |

| PO/2’-fluorine/2’-OMe, aptamer | N/A | 0.42 | 4.88 | Rat | [95] |

| Linear, 20 kDa | 1.47 | 7.23 | |||

| Y-Shaped, 40 kDa | 0.60 | 11.68 | |||

| PO/2’-fluorine/2’-OMe, aptamer | 2-Arm, 40 kDa | N/A | 4.3 | Mouse | [103] |

| 4-Arm, 40 kDa | N/A | 5.0 | |||

| 2-Arm, 80 kDa | N/A | 7.5 | |||

| 4-Arm, 80 kDa | N/A | 10.5 | |||

| PO+PS/2’-OMe, aptamer | Linear, 20 kDa | N/A | ~ 2 | Human | [92] |

Plasma half-life.

In the literature and clinical trials, there is a growing number of PEGylated ONs with slightly branched PEG [98–101]. Slightly branched PEG is defined as loosely distributed PEG side chains connected to a central core, including Y-shaped PEG and three- to six-armed stars. The reactive moieties of slightly branched PEG are typically located at the core instead of at the terminus, allowing the conjugated ON to experience a higher-density PEG environment. Pegaptanib contains a 40 kDa Y-shaped PEG, which causes the binding affinity to decrease fourfold compared with the parent aptamer [102]. Nonetheless, the inhibition of VEGF-induced permeability (Miles assay) is increased to 83% from 48%. This phenomenon is attributed to prolonged tissue residence [50]. Haruta et al. have compared several PEG-aptamer conjugates with 80 kDa (two or one arms) and 40 kDa (two or four arms) PEG [103]. It was found that increasing the number of arms (each arm having the same MW) positively affected plasma t1/2β. Given the same total PEG MW (equals the number of arms times the MW of each arm), longer t1/2β was achieved with higher arm numbers, although each arm is shorter. Moreover, it was found that the branched PEG increased the aptamer’s ability to bind to interleukin 17A (IL-17A) twofold, instead of decreasing it. These results suggest that branched PEG structures with multiple side chains may provide higher local PEG densities that can improve the protective efficacy of PEG beyond what linear, high-MW PEG can achieve. Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate the limits of increasing local PEG densities by means of multiarm architectures.

3. Highly branched PEG-ON architectures

Brush-type polymers are structures with a linear backbone, from which multiple side chains emanate [104]. Brush architecture PEG (bPEG) consists of PEG side chains attached to the main backbone and can be made by grafting side chains to the backbone (graft-onto), by forming side chains via polymerization from a backbone containing initiators (graft-from), or by direct polymerization of side chain macromonomers having a polymerizable end group (graft-through) [105–107]. The number of PEG chains and their MW dictate the local density of the PEG, and thus the level of macromolecular shielding. Thus, it is possible to tune the density by controlling the degree of polymerization (DP) of the backbone and the length of the side chains.

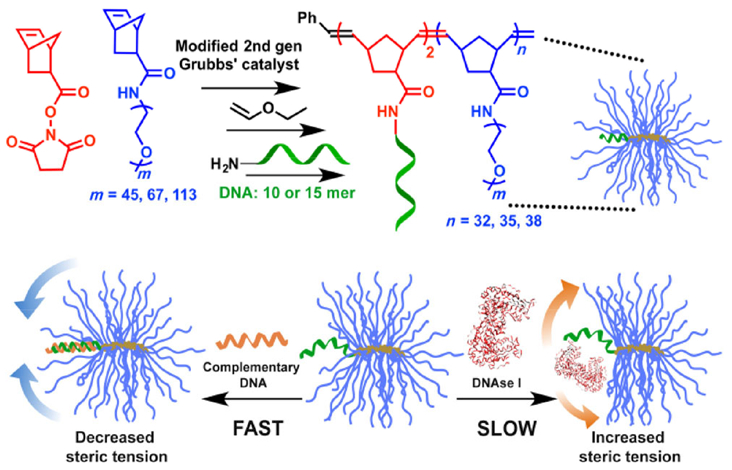

Our group has developed a new form of PEGylated ON, termed polymer-assisted compaction of ON (pacON), which consists of a small number of ONs (typically 1–5) tethered to the backbone of the bPEG via 3′, 5′, or an internal position of the ON (Fig. 2) [57, 62]. The bPEG of pacON hides the ON within an intermediate-density local PEG environment, which is much higher compared with linear PEG-ON conjugates, but well below the saturation concentration of PEG in an aqueous solution. This unique density range provides the pacON with nanoscale binding selectivity: ON hybridization with a slender, complementary strand is unaffected, but access for proteins, which are much larger in cross-section diameter, is significantly hindered. Such selectivity is important for ON-based therapeutics because enzymatic degradation and most of unwanted clinical side effects stem from specific and non-specific ON-protein interactions. Therefore, with the pacON, it is possible to apply native, unmodified phosphodiesters for effective therapy with sufficient plasma stability and fewer side effects. In addition, the bPEG structure is sufficiently large to avoid renal clearance. Due to the “stealth” property of PEG, blood circulation time is expected to be significantly improved, allowing for targeting of additional tissues and organs (e.g., tumor) other than the liver, which is the primary target of current systemically administered ON drugs. It is also observed that the pacONs enter cells and regulate cellular gene expression without the use of additional transfection agents much more effectively than linear PEG-ON conjugates and free ONs. These properties make the pacON a potential alternative to phosphorothioates. It may also be beneficial to combine bPEG and phosphorothioates to take advantage of the favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics of the former and the physiological stability of the latter in certain use cases.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of pacDNA and mechanism of its steric selectivity (reprinted with permission from Ref. [57], © American Chemical Society 2015).

To achieve desired selectivity, the backbone DP and the MW of the PEG side chains must be sufficiently high, so that the radius of the PEG environment can shelter the entire length of the ON. We have synthesized a small library of pacDNAs with 2–10 kDa PEG side chains and two DNA lengths (10- and 15-mers) to systematically investigate the structure–property relation. All pacDNAs hybridize immediately with complementary strands upon mixing with similar kinetics to free DNA, suggesting that bPEG does not create noticeable steric barrier against linear ONs. When an enzyme (DNase I, which nonspecifically degrades double-stranded DNA) is added to prehybridized free DNA or pacDNA, free strands are rapidly degraded with half-life < 10 min. On the other hand, pacDNA improves the half-life by up to twentyfold. Longer PEG side chains generally lead to better protection. To achieve a ~ 20× increase in nuclease half-life for the 10- and 15-mer DNAs, PEG side chain MW of 5 and 10 kDa is needed, respectively. On the other hand, a low-density, Y-shape PEG-ON conjugate (20 kDa each arm) manifests only 2× longer half-life. The bPEG with lower backbone DP values has properties similar to those of Y-shaped PEG because the limited local PEG density cannot create the necessary steric congestion. For a 5 kDa bPEG, the shielding capacity reaches a plateau when backbone DP = 26, which coincides with the structural transition of the brush from spherical to cylindrical, suggesting that steric congestion can be maximized and further increases of the DP cannot provide additional protective benefits.

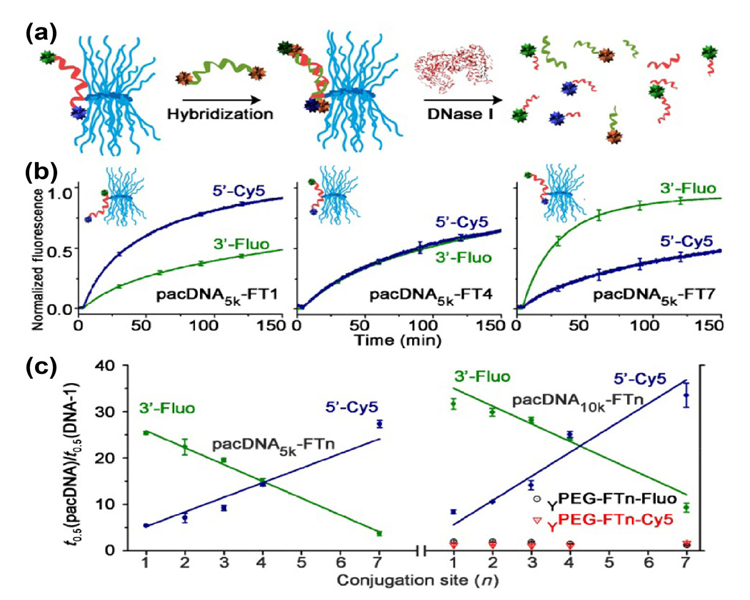

Although these studies indicate that a longer PEG side chain and brush backbone lengths yield better protection, the picture is still rough. To obtain a higher-resolution understanding of the degree of protein shielding as a function of depth towards the brush core, a series of 21-mer probes were designed and synthesized (Fig. 3) [62]. Each probe contains two different fluorophores (one at the 5′ end and the other at the 3′ end), and an anchor point located on a base within the sequence, which is used to conjugate with the bPEG. By adjusting the position of the anchor point, the degree of exposure of the ON termini can be fine-tuned with depth resolution of a single nucleotide. Using these probes, an enzymatic stability “depth-profile” was created, showing that, for each nucleotide’s distance towards the backbone, an increase of 1.0–1.5× in the half-life of naked ON can be expected. These results also indicate that, when a mid-ON anchor point is used, a smaller brush can be used to protect a longer ON without a loss of protection. Thus, with a bPEG having 10 kDa PEG side chains, an ON as long as a 30-mer can be properly protected (with a > 15× increase in nuclease half-life).

Figure 3.

(a) Schematics of PEG-DNA probes and FRET-based nuclease stability assay. (b) Representative degradation kinetics of pacDNAs. (c) Enzyme half-life as a function of DNA conjugation position. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [62]. © American Chemical Society 2017.

To test the protein-shielding ability of pacONs in a more complex biological fluid, pacONs consisting of an antithrombin aptamer was compared with free aptamer in human plasma for their ability to prolong blood coagulation. The interaction between ON and proteins involved in the coagulation pathway contributes to coagulopathy (observed with certain ON formulations in clinical trials), which can increase patients’ risk of bleeding [108, 109]. Although free aptamer is found to significantly increase the aPTT and prothrombin time (PT) upon introduction of a coagulation-inducing agent, pacDNA shows nearly no prolongation in both tests. The ability of pacONs to evade protein binding in plasma is translated to a more favorable pharmacokinetic behavior in vivo in a mouse model. Both pacDNA and pac-siRNA (unpublished) were found to circulate in the blood stream for an extended period and to passively accumulate in tumor tissues (subcutaneous xenograft), likely through the enhanced permeation and retention effect [110]. In contrast, a small bPEG with 2 kDa side chains (overall MW: 76 kDa) was still found to clear via kidneys. These data indicate that systemic delivery does not necessarily rely upon the use of phosphorothioates, which adheres to plasma proteins to avoid renal clearance; pacONs can be sufficiently large on their own to bypass glomerular filtration and can offer better blood retention times, and thus target nonliver tissues [57, 111, 112].

One concern about ON-based therapies is the adverse events associated with unwanted activation of the innate immune system, e.g., by the CpG motifs that are present in certain ON sequences (e.g., oblimersen) [113, 114]. In fact, grade I or II flulike symptoms (pyrexia and fatigue) are the most commonly reported side effects in clinical trials for nucleic acid-based therapies [115]. The phase I clinical trial of TKM-ApoB, an siRNA-based therapy for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, was terminated due to adverse events associated with immune system activation [116, 117]. ONs can initiate immune responses by binding with toll-like receptors (TLRs), which then trigger the production of inflammatory cytokines [118]. We studied pacDNAs carrying a CpG-rich sequence in a macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7) [61]. The production of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-β, and IL-6) at both RNA and protein levels was significantly reduced compared with Lipofectamine-transfected free ON. On a per-strand-internalized basis, the pacON also exhibited much less TLR9 activation compared with Y-shape PEG-ON conjugates (40 kDa), which cannot effectively shield the ON from receptor recognition. Of note, a much higher concentration of the Y-shaped conjugate was employed for this comparison because pacONs enters macrophage cells much more readily than free ON and linear or slightly branched PEG-ON conjugates.

As for macrophage cells, pacONs enter a variety of cancer cell lines to a greater extent (10–20×) than free phosphodiester ONs, including breast cells (SKBR3, 4T1), ovarian cells (SKOV3), and cervical cells (HeLa). The uptake is size-dependent, with larger bPEG particles leading to greater uptake. On average, ~ 0.5–1 million pacON particles having 10 kDa PEG side chains are internalized by a single SKOV3 cell (incubated for 6 h with 1 μM pacON). PacDNAs enter cells through caveolae- and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Intracellular trafficking studies indicate that pacDNAs originate in early endosomes and progress to late endosomes, but not to lysosomes (likely exocytosed after late endosome). The extent of endosomal escape to cytosol is unclear. On the other hand, biochemical readout (mRNA levels and protein levels) using pacDNA carrying anti-HER2 antisense strands indicates an effective knockdown in SKOV3 cells, even at low concentrations (10 nM, with no transfection agent used), suggesting some level of endosomal escape [58]. The antisense activity of pacDNA is significantly higher than that of linear or slightly branched PEG-ON conjugates and is comparable with that involving polycationic carriers. The superior antisense efficacy of the pacON is attributed to a combination of enhanced cellular uptake and improved stability. A series of antisense pacONs targeting Bcl-2 with the same overall size (and thus cellular uptake) but varying enzymatic stability, achieved via different anchor points along the antisense sequence, showed a positive correlation between enzymatic stability and antisense activity. Given that pacONs consist primarily of nucleic acids and PEG, which is “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) by regulatory agencies [119], pacONs are found to be noncytotoxic in several cell lines even at high concentrations.

The unique properties of the pacON stem from increased PEG steric hindrance, which is not limited to brush architectures and may be generated by other nanostructures such as polymeric micelles. To demonstrate, we have prepared block copolymer comicelles consisting of DNA-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), PEG-b-PCL, and the homopolymer PCL [60]. The homopolymer allows for fine-tuning of the spacing of micelle surface moieties through dilution of the micellar core. The results indicated that the accessibility of the ON by a complementary DNA and enzyme (DNase I) can both be affected by the surface PEG density. Enzyme accessibility becomes affected only at intermediate and high densities, which explains why ONs conjugated to linear PEG are typically not adequately shielded from degradation. At the highest PEG densities (no PCL dilution), accessibility by a complementary ON also becomes reduced, both in extent and kinetics. These studies demonstrate that an optimal, intermediate PEG density is required to maximize the availability of ONs for hybridization while offering sufficient protein shielding. Among several factors, including cellular uptake, hybridization readiness, and nuclease resistance, the last factor has the strongest correlation with the overall in vitro antisense activity, consistent with previous bPEG-based results. These findings reveal a series of fundamental, nonmonotonic structure–activity relations for PEGylated ONs and define a promising new path for exploring ON therapeutics that does not involve cationic vectors.

4. Conclusions and perspectives

The development of PEGylated ONs has spread into a span of more than 30 years. Research efforts have been focused on the use of linear or slightly branched PEG in the synthesis of PEG-ON conjugates. A plethora of information has been obtained regarding the influence of PEG MW, of the conjugation site of the ON, and of PEG terminal group on the pharmacokinetics, cellular uptake, and overall efficacy of the conjugate. Many forms of ONs, including antisense, aptamer, siRNA, and miRNA have been PEGylated, and one PEGylated aptamer has received regulatory approval. It is recognized that PEGylation alone may not achieve the necessary biopharmaceutical improvement for ON drugs, and a combination with another chemical modification is needed. With the popular use of phosphorothioate ONs, which show improvement in bioavailability, enzyme stability, and efficacy, PEGylation is oftentimes not carried out due to the lack of significant additional benefits. Nonetheless, phosphorothioates are imperfect, showing reduced binding affinity and nonspecific stress and toxic responses, and alternatives are still sought after.

Brush-type PEG-ON conjugates have recently emerged as a new class of ON material intended as therapeutic agents. Termed pacON, the conjugate exhibits selective binding with complementary sequence over proteins, which originates from the increased local PEG density of the brush architecture relative to linear or slightly branched PEG. The pacON shows significantly improved nuclease resistance, cellular uptake, and gene knockdown efficiency when an antisense sequence is used. Due to the reduction of protein−ON interactions, side effects including unwanted inflammatory responses and prolongation of blood coagulation can be greatly reduced. The pacON also manifests enhanced blood circulation time and ability to passively target tumor tissues via the enhanced permeation and retention effect. These data suggest that the pacON may be used to enhance the biopharmaceutical properties of both unmodified phosphodiester ONs and phosphorothioates and allow for the targeting of nonliver tissues via systemic delivery. Further in vivo studies are needed to validate these ideas. An area of concern with regard to PEGylated ONs is pre-existing anti-PEG immunity due to the widespread use of PEG in nonpharmaceutical applications [120, 121]. Pegnivacogin, a 31-mer RNA aptamer with 40 kDa Y-shaped PEG modification, was terminated in Phase IIb trial due to three cases of severe allergic reactions [122]. The three patients were later found to have elevated levels of IgG anti-PEG antibodies. Possible work-arounds include screening of patients for existing anti-PEG immunity and adoption of other biocompatible “stealth” materials, e.g., zwitterionic polymers, to replace PEG in brushes and other types of elevated-density architectures [123, 124]. The pacONs highlight the importance of local density for macromolecular shielding and represent a departure from traditional liposome- and polycationic-carrier-based approaches.

Linear and highly branched PEG each have their own areas of applicability (Table 2). Linear or slightly branched PEG is broadly applicable because the modification can be designed to minimize negative impact on RNase H activity (antisense), the loading or function of RISC (siRNA), and interaction with target proteins (aptamers). Nonetheless, linear PEG is not widely employed for antisense, miRNA, and siRNA applications owing to reduced cellular uptake and the fact that phosphorothioates often offer better results. Currently, the best use case for linear or slightly branched PEG is the PEGylation of aptamers. Phosphorothioates may not be as appropriate for aptamers because the modification promotes nonspecific plasma protein binding. Although PEGylation may reduce the binding affinity of the aptamer for its target, the drawback can be outweighed by the pharmacokinetic benefits.

Table 2.

Comparison of linear or slightly branched PEG and highly branched PEG

| Linear and slightly branched PEG | Highly branched PEG | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular size | Small (typically < 80 kDa); cannot bypass renal clearance; phosphorothioate ON needed | Large (typically 150–300 kDa); can avoid renal clearance without phosphorothioate ON | [57, 87] |

| Local PEG densitya | Low (110–130 g/L) | Intermediate (140–160 g/L) | [54, 55, 59, 60, 86] |

| ON hybridization thermodynamics | Increased binding affinity than free ON | Similar binding affinity to free ON | [57, 59, 65, 84] |

| Protein shielding | Low | High | [57, 60, 61, 62, 65, 72, 84] |

| -Enzymatic stability | Similar to unmodified ON | 10–30× longer half-life than unmodified ON | |

| -TLR activation | Similar to unmodified ONb | Significantly reduced | |

| -Coagulopathy | Lower compared with unmodified ON | Lower compared with unmodified ON | |

| Cell uptake | Similar to phosphodiester ON; much lower compared with phosphorothioate ON | 10–20× higher than phosphodiester ON; lower compared with phosphorothioate ON | [20, 58, 60 62, 87] |

| Plasma PK | Rapid clearance from plasma (< 1% in minutes); t1/2β ~ 10–20 h; 2–5× higher area under the curve (AUC) than free ONc | Significantly improved blood circulation and AUC than free ONd | [57, 92–95, 103] |

| Biodistribution | Rapid distribution into kidney and liverc | Distributes to permeable tissues including tumor | [57, 95] |

| Target tissue | Primarily liver | Possibly non-liver tissues | [57] |

| Use case | Best for aptamers. Phosphorothioates and other chemical modifications are required/preferred for non-aptamer conjugates | Non-releasable: antisense gene regulation (RNase H-independent) and antagonizing excess miRNA Releasable: siRNA, supply of depleted miRNA, aptamer |

[50, 58, 80, 83] |

Densities of PEG are estimated from MW and number-average hydrodynamic volume of the polymer, as determined by dynamic light scattering.

On a per-strand-internalized basis.

With phosphorothioate ON.

With phosphodiester ON.

On the other hand, ON PEGylation via highly branched PEG (e.g., brushes, stars, and PEG micelles) appears to be limited to a smaller number of use cases because bPEG inhibits the access of all proteins to the ON, including those intended for interaction with the ON. An obvious application is antisense gene regulation because RNase H activity is not necessary; physical blockage of the translation process alone can be effective. Another possibility is to use a pacON to antagonize upregulated miRNA or a pac-aptamer to capture small-molecule targets. To expand the usability range of pacONs, a releasable mechanism, such as those activated by the reductive cellular environment, reactive oxygen species, pH differences, or externally delivered light, can be used [125]. For example, a releasable pac-siRNA may allow a native RNA duplex to engage with the RNAi after circulating in blood and reaching a target tissue. The supply of depleted miRNA and delivery of aptamers are also possible. Therefore, the full range of applications of highly branched PEG in ON therapeutics remains to be explored.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Award Number 1R01GM121612-01, the National Science Foundation (CAREER Award Number 1453255), and the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (No. PRF 54905-DNI5), is acknowledged.

References

- [1].Khvorova A; Watts JK The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility. Nat. Biotechnol 2017, 35, 238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cohen JS Informational drugs: A new concept in pharmacology. Antisense Res. Dev 1991, 1, 191–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Crooke ST Therapeutic applications of oligonucleotides. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 1992, 32, 329–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].DiMasi JA; Hansen RW; Grabowski HG The price of innovation: New estimates of drug development costs. J. Health Econ 2003, 22, 151–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jain KK Personalized medicine. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther 2002, 4, 548–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Powledge TM Human genome project completed. Genome Biol. 2003, 4, spotlight-20030415–01. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Metzker ML Sequencing technologies—The next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet 2010, 11, 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stein CA; Castanotto D FDA-approved oligonucleotide therapies in 2017. Mol. Ther 2017, 25, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Friedmann T Human gene therapy—An immature genie, but certainly out of the bottle. Nat. Med 1996, 2, 144–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Verma IM; Somia N Gene therapy-promises, problems and prospects. Nature 1997, 389, 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Abdelhady HG; Allen S; Davies MC; Roberts CJ; Tendler SJB; Williams PM Direct real-time molecular scale visualisation of the degradation of condensed DNA complexes exposed to DNase I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 4001–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Geary RS Antisense oligonucleotide pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol 2009, 5, 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang K; Fang HF; Wang ZH; Taylor J-SA; Wooley KL Cationic shell-crosslinked knedel-like nano-particles for highly efficient gene and oligonucleotide transfection of mammalian cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 968–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lächelt U; Wagner E Nucleic acid therapeutics using polyplexes: A journey of 50 years (and beyond). Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 11043–11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu G; Swierczewska M; Lee S; Chen XY Functional nanoparticles for molecular imaging guided gene delivery. Nano Today 2010, 5, 524–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Akinc A; Zumbuehl A; Goldberg M; Leshchiner ES; Busini V; Hossain N; Bacallado SA; Nguyen DN; Fuller J; Alvarez R et al. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol 2008, 26, 561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Deleavey GF; Damha MJ Designing chemically modified oligonucleotides for targeted gene silencing. Chem. Biol 2012, 19, 937–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yin H; Kanasty RL; Eltoukhy AA; Vegas AJ; Dorkin JR; Anderson DG Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet 2014, 15, 541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Taylor WJ; Ott J; Eckstein F The rapid generation of oligonucleotide-directed mutations at high frequency using phosphorothioate-modified DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985, 13, 8765–8785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Beltinger C; Saragovi HU; Smith RM; LeSauteur L; Shah N; DeDionisio L; Christensen L; Raible A; Jarett L; Gewirtz AM Binding, uptake, and intracellular trafficking of phosphorothioate-modified oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Clin. Invest 1995, 95, 1814–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sands H; Gorey-Feret LJ; Cocuzza AJ; Hobbs FW; Chidester D; Trainor GL Biodistribution and metabolism of internally 3h-labeled oligonucleotides. I. Comparison of a phosphodiester and a phosphorothioate. Mol. Pharmacol 1994, 45, 932–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Prakash TP; Bhat B 2’-Modified oligonucleotides for antisense therapeutics. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2007, 7, 641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schmidt K; Prakash TP; Donner AJ; Kinberger GA; Gaus HJ; Low A; Østergaard ME; Bell M; Swayze EE; Seth PP Characterizing the effect of galnac and phosphorothioate backbone on binding of antisense oligonucleotides to the asialoglycoprotein receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 2294–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schechter PJ; Martin RR Safety and tolerance of phosphorothioates in humans In Antisense Research and Application. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Crooke ST, Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1998; Vol. 131, pp 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Henry SP; Templin MV; Gillett N; Rojko J; Levin AA Correlation of toxicity and pharmacokinetic properties of a phosphorothioate oligonucleotide designed to inhibit ICAM-1. Toxicol. Pathol 1999, 27, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ho SP; Livanov V; Zhang W; Li J-H; Lesher T Modification of phosphorothioate oligonucleotides yields potent analogs with minimal toxicity for antisense experiments in the CNS. Mol. Brain Res 1998, 62, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gleave ME; Monia BP Antisense therapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 468–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sharma VK; Rungta P; Prasad AK Nucleic acid therapeutics: Basic concepts and recent developments. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 16618–16631. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fang XH; Tan WH Aptamers generated from cell-SELEX for molecular medicine: A chemical biology approach. Acc. Chem. Res 2010, 43, 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bestas B; Moreno PM; Blomberg KEM; Mohammad DK; Saleh AF; Sutlu T; Nordin JZ; Guterstam P; Gustafsson MO; Kharazi S et al. Splice-correcting oligonucleotides restore BTK function in X-linked agammaglobulinemia model. J. Clin. Invest 2014, 124, 4067–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pelechano V; Steinmetz LM Gene regulation by antisense transcription. Nat. Rev. Genet 2013, 14, 880–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Crooke ST Vitravene™—Another piece in the mosaic. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1998, 8, vii–viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sridharan K; Gogtay NJ Therapeutic nucleic acids: Current clinical status. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 2016, 82, 659–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Santos RD; Raal FJ; Catapano AL; Witztum JL; Steinhagen-Thiessen E; Tsimikas S Mipomersen, an antisense oligonucleotide to apolipoprotein B-100, reduces lipoprotein(a) in various populations with hypercholesterolemia: Results of 4 phase III trials. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 2015, 35, 689–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gouni-Berthold I; Berthold HK Mipomersen and lomitapide: Two new drugs for the treatment of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis Suppl. 2015, 18, 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Corey DR Nusinersen, an antisense oligonucleotide drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Neurosci 2017, 20, 497–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Aartsma-Rus A; Krieg AM FDA approves eteplirsen for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: The next chapter in the eteplirsen saga. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2017, 27, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hannon GJ RNA interference. Nature 2002, 418, 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kole R; Krainer AR; Altman S RNA therapeutics: Beyond RNA interference and antisense oligonucleotides. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2012, 11, 125–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Whitehead KA; Dorkin JR; Vegas AJ; Chang PH; Veiseh O; Matthews J; Fenton OS; Zhang YL; Olejnik KT; Yesilyurt V et al. Degradable lipid nanoparticles with predictable in vivo siRNA delivery activity. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Suhr OB; Coelho T; Buades J; Pouget J; Conceicao I; Berk J; Schmidt H; Waddington-Cruz M; Campistol JM; Bettencourt BR et al. Efficacy and safety of patisiran for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: A phase II multi-dose study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 2015, 10, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rizk M; Tüzmen Ş Update on the clinical utility of an RNA interference-based treatment: Focus on Patisiran. Pharmacogenomics Pers. Med 2017, 10, 267–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Huang YY Preclinical and clinical advances of GalNAC-decorated nucleic acid therapeutics. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 6, 116–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].He L; Hannon GJ MicroRNAs: Small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet 2004, 5, 522–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jazbutyte V; Thum T MicroRNA-21: From cancer to cardiovascular disease. Curr. Drug Targets 2010, 11, 926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kosaka N; Iguchi H; Ochiya T Circulating microRNA in body fluid: A new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2010, 101, 2087–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Agostini M; Knight RA miR-34: From bench to bedside. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 872–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Thakral S; Ghoshal K miR-122 is a unique molecule with great potential in diagnosis, prognosis of liver disease, and therapy both as miRNA mimic and antimir. Curr. Gene Ther. 2015, 15, 142–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tuerk C; Gold L Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ng EWM; Shima DT; Calias P; Cunningham ET Jr.; Guyer DR; Adamis AP Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Li WJ; Zhan P; De Clercq E; Lou HX; Liu XY Current drug research on PEGylation with small molecular agents. Prog. Polym. Sci 2013, 38, 421–444. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Harris JM; Chess RB Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2003, 2, 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Harris JM; Martin NE; Modi M Pegylation. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2001, 40, 539–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Plesner B; Fee CJ; Westh P; Nielsen AD Effects of PEG size on structure, function and stability of PEGylated BSA. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2011, 79, 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Nakano S-I; Karimata H; Ohmichi T; Kawakami J; Sugimoto N The effect of molecular crowding with nucleotide length and cosolute structure on DNA duplex stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 14330–14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schöttler S; Becker G; Winzen S; Steinbach T; Mohr K; Landfester K; Mailänder V; Wurm FR Protein adsorption is required for stealth effect of poly (ethylene glycol)-and poly (phosphoester)-coated nanocarriers. Nat. Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lu XG; Tran T-H; Jia F; Tan XY; Davis S; Krishnan S; Amiji MM; Zhang K Providing oligonucleotides with steric selectivity by brush-polymer-assisted compaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 12466–12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lu XG; Jia F; Tan XY; Wang DL; Cao XY; Zheng JM; Zhang K Effective antisense gene regulation via noncationic, polyethylene glycol brushes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 9097–9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Jia F; Lu XG; Tan XY; Wang DL; Cao XY; Zhang K Effect of peg architecture on the hybridization thermodynamics and protein accessibility of PEGylated oligonucleotides. Angew. Chem 2017, 129, 1259–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wang DL; Lu XG; Jia F; Tan XY; Sun XY; Cao XY; Wai F; Zhang C; Zhang K Precision tuning of DNA- and poly(ethylene glycol)-based nanoparticles via coassembly for effective antisense gene regulation. Chem. Mater 2017, 29, 9882–9886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cao XY; Lu XG; Wang DL; Jia F; Tan XY; Corley M; Chen XY; Zhang K Modulating the cellular immune response of oligonucleotides by brush polymer-assisted compaction. Small 2017, 13, 1701432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Jia F; Lu XG; Wang DL; Cao XY; Tan XY; Lu H; Zhang K Depth-profiling the nuclease stability and the gene silencing efficacy of brush-architectured poly(ethylene glycol)–DNA conjugates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 10605–10608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Prencipe G; Tabakman SM; Welsher K; Liu Z; Goodwin AP; Zhang L; Henry J; Dai HJ PEG branched polymer for functionalization of nanomaterials with ultralong blood circulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 4783–4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jäschke A; Fürste JP; Cech D; Erdmann VA Automated incorporation of polyethylene glycol into synthetic oligonucleotides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jäschke A; Fürste JP; Nordhoff E; Hillenkamp F; Cech D; Erdmann VA Synthesis and properties of oligodeoxyribonucleotide—Polyethylene glycol conjugates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4810–4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Jia F; Lu XG; Tan XY; Zhang K Facile synthesis of nucleic acid–polymer amphiphiles and their self-assembly. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 7843–7846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bonora GM; Ivanova E; Zarytova V; Burcovich B; Veronese FM Synthesis and characterization of high-molecular mass polyethylene glycol-conjugated oligonucleotides. Bioconjugate Chem. 1997, 8, 793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Boora GM Polyethylene glycol: A high-efficiency liquid phase (HELP) for the large-scale synthesis of the oligonucleotides. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 1995, 54, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Livingston AG; Peeva LG; Silva P Organic solvent nanofiltration. In Membrane Technology: In the Chemical Industry, 2nd ed.; Nunes SP; Peinemann KV, Eds.; Wiley: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kim JF; Gaffney PR; Valtcheva IB; Williams G; Buswell AM; Anson MS; Livingston AG Organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN): A new technology platform for liquid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis (LPOS). Org. Process Res. Dev 2016, 20, 1439–1452. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Gaffney PRJ; Kim JF; Valtcheva IB; Williams GD; Anson MS; Buswell AM; Livingston AG Liquid-phase synthesis of 2′-methyl-RNA on a homostar support through organic-solvent nanofiltration. Chem.—Eur. J 2015, 21, 9535–9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Elsabahy M; Zhang MZ; Gan S-M; Waldron KC; Leroux J-C Synthesis and enzymatic stability of PEGylated oligonucleotide duplexes and their self-assemblies with polyamidoamine dendrimers. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ikeda Y; Nagasaki Y Impacts of PEGylation on the gene and oligonucleotide delivery system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 2014, 131, 40293. [Google Scholar]

- [74].Jäschke A Oligonucleotide-poly (ethylene glycol) conjugates: Synthesis, properties, and applications In ACS Symposium Series; ACS Publications: American, 1997; Vol. 680, pp 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- [75].D’Onofrio J; Montesarchio D; De Napoli L; Di Fabio G An efficient and versatile solid-phase synthesis of 5’- and 3’-conjugated oligonucleotides. Org. Lett 2005, 7, 4927–4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sosic A; Pasqualin M; Pasut G; Gatto B Enzymatic formation of PEGylated oligonucleotides. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Shaw J-P; Kent K; Bird J; Fishback J; Froehler B Modified deoxyoligonucleotides stable to exonuclease degradation in serum. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 747–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Graham MJ; Crooke ST; Monteith DK; Cooper SR; Lemonidis KM; Stecker KK; Martin MJ; Crooke RM In vivo distribution and metabolism of a phosphorothioate oligonucleotide within rat liver after intravenous administration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1998, 286, 447–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Czauderna F; Fechtner M; Dames S; Aygün H; Klippel A; Pronk GJ; Giese K; Kaufmann J Structural variations and stabilising modifications of synthetic siRNAs in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 2705–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Jung S; Lee SH; Mok H; Chung HJ; Park TG Gene silencing efficiency of siRNA-PEG conjugates: Effect of PEGylation site and PEG molecular weight. J. Control. Release 2010, 144, 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Shokrzadeh N; Winkler A-M; Dirin M; Winkler J Oligonucleotides conjugated with short chemically defined polyethylene glycol chains are efficient antisense agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24, 5758–5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Manoharan M 2′-Carbohydrate modifications in antisense oligonucleotide therapy: Importance of conformation, configuration and conjugation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1489, 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Govan JM; McIver AL; Deiters A Stabilization and photochemical regulation of antisense agents through PEGylation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22, 2136–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Kawaguchi T; Asakawa H; Tashiro Y; Juni K; Sueishi T Stability, specific binding activity, and plasma concentration in mice of an oligodeoxynucleotide modified at 5’-terminal with poly (ethylene glycol). Biol. Pharm. Bull 1995, 18, 474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Miyoshi D; Sugimoto N Molecular crowding effects on structure and stability of DNA. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1040–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Nakano S-I; Miyoshi D; Sugimoto N Effects of molecular crowding on the structures, interactions, and functions of nucleic acids. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 2733–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Geary RS; Norris D; Yu R; Bennett CF Pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and cell uptake of antisense oligonucleotides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2015, 87, 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Geary RS; Baker BF; Crooke ST Clinical and preclinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of mipomersen (kynamro®): A second-generation antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of apolipoprotein B. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2015, 54, 133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Reyderman L; Stavchansky S Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of a nucleotide-based thrombin inhibitor in rats. Pharm. Res 1998, 15, 904–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Zhao H; Greenwald RB; Reddy P; Xia J; Peng P A new platform for oligonucleotide delivery utilizing the peg prodrug approach. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005, 16, 758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Tucker CE; Chen L-S; Judkins MB; J. A; Gill SC; Drolet DW Detection and plasma pharmacokinetics of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor oligonucleotide-aptamer (NX1838) in rhesus monkeys. J. Chromatogr. B 1999, 732, 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Gilbert JC; DeFeo-Fraulini T; Hutabarat RM; Horvath CJ; Merlino PG; Marsh HN; Healy JM; BouFakhreddine S; Holohan TV; Schaub RG First-in-human evaluation of anti-von willebrand factor therapeutic aptamer ARC1779 in healthy volunteers. Circulation 2007, 116, 2678–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Raynaud FI; Orr RM; Goddard PM; Lacey HA; Lancashire H; Judson IR; Beck T; Bryan B; Cotter FE Pharmacokinetics of G3139, a phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotide antisense to bcl-2, after intravenous administration or continuous subcutaneous infusion to mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1997, 281, 420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Zhao H; Peng P; Longley C; Zhang Y; Borowski V; Mehlig M; Reddy P; Xia J; Borchard G; Lipman J et al. Delivery of G3139 using releasable PEG-linkers: Impact on pharmacokinetic profile and anti-tumor efficacy.J. Control. Release 2007, 119, 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Healy JM; Lewis SD; Kurz M; Boomer RM; Thompson KM; Wilson C; McCauley TG Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of novel aptamer compositions. Pharm. Res 2004, 21, 2234–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].McCauley TG; Kurz JC; Merlino PG; Lewis SD; Gilbert M; Epstein DM; Marsh HN Pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic assessment of anti-TGFβ2 aptamers in rabbit plasma and aqueous humor. Pharm. Res 2006, 23, 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Yamaoka T; Tabata Y; Ikada Y Distribution and tissue uptake of poly (ethylene glycol) with different molecular weights after intravenous administration to mice. J. Pharm. Sci 1994, 83, 601–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Kang HG; Park JK; Seu YB; Hahn SK A novel branch-type PEGylation of aptamer therapeutics. Key Eng. Mater 2007, 342–343, 529–532. [Google Scholar]

- [99].Burcovich B; Veronese FM; Zarytova V; Bonora GM Branched polyethylene glycol (bPEG) conjugated antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleos. Nucleot 1998, 17, 1567–1570. [Google Scholar]

- [100].Hoellenriegel J; Zboralski D; Maasch C; Rosin NY; Wierda WG; Keating MJ; Kruschinski A; Burger JA The spiegelmer NOX-A12, a novel CXCL12 inhibitor, interferes with chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell motility and causes chemosensitization. Blood 2014, 123, 1032–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Vater A; Klussmann S Turning mirror-image oligonucleotides into drugs: The evolution of Spiegelmer® therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Ruckman J; Green LS; Beeson J; Waugh S; Gillette WL; Henninger DD; Claesson-Welsh L; Janjic N 2′-Fluoropyrimidine RNA-based aptamers to the 165-amino acid form of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165): Inhibition of receptor binding and VEGF-induced vascular permeability through interactions requiring the exon 7-encoded domain. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 20556–20567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Haruta K; Otaki N; Nagamine M; Kayo T; Sasaki A; Hiramoto S; Takahashi M; Hota K; Sato H; Yamazaki H A novel PEGylation method for improving the pharmacokinetic properties of anti-interleukin-17A RNA aptamers. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2017, 27, 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Milner ST Polymer brushes. Science 1991, 251, 905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Zdyrko B; Luzinov I Polymer brushes by the “grafting to” method. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Johnson JA; Lu YY; Burts AO; Lim Y-H; Finn MG; Koberstein JT; Turro NJ; Tirrell DA; Grubbs RH Core-clickable PEG-branch-azide bivalent-bottle-brush polymers by ROMP: Grafting-through and clicking-to. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 559–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Zhang MF; Müller AHE Cylindrical polymer brushes. J. Polym. Sci. A: Polym. Chem 2005, 43, 3461–3481. [Google Scholar]

- [108].Henry SP; Novotny W; Leeds J; Auletta C; Kornbrust DJ Inhibition of coagulation by a phosphorothioate oligonucleotide. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997, 7, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Stevenson JP; Yao K-S; Gallagher M; Friedland D; Mitchell EP; Cassella A; Monia B; Kwoh TJ; Yu R; Holmlund J et al. Phase I clinical/pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic trial of the c-raf-1 antisense oligonucleotide ISIS 5132 (CGP 69846A). J. Clin. Oncol 1999, 17, 2227–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Maeda H; Wu J; Sawa T; Matsumura Y; Hori K Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: A review. J. Control. Release 2000, 65, 271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Li SD; Huang L Stealth nanoparticles: High density but sheddable PEG is a key for tumor targeting. J. Control. Release 2010, 145, 178–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Perry JL; Reuter KG; Kai MP; Jones WS; Luft JC; Napier M; Bear JE; DeSimone JM PEGylated PRINT nanoparticles: The impact of PEG density on protein binding, macrophage association, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 5304–5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Hemmi H; Takeuchi O; Kawai T; Kaisho T; Sato S; Sanjo H; Matsumoto M; Hoshino K; Wagner H; Takeda K et al. Erratum a toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 2001, 409, 646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Stetson DB; Medzhitov R Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity 2006, 24, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Barar J; Omidi Y Translational approaches towards cancer gene therapy: Hurdles and hopes. BioImpacts 2012, 2, 127–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Xu C-F; Wang J Delivery systems for siRNA drug development in cancer therapy. Asian J. Pharm. Sci 2015, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- [117].Zatsepin TS; Kotelevtsev YV; Koteliansky V Lipid nanoparticles for targeted siRNA delivery—Going from bench to bedside. Int. J. Nanomed 2016, 11, 3077–3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Bode C; Zhao G; Steinhagen F; Kinjo T; Klinman DM CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2011, 10, 499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Working PK; Newman MS; Johnson J; Cornacoff JB Safety of poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(ethylene glycol) derivatives In ACS Symposium Series; ACS Publications: American, 1997; Vol. 680, pp 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- [120].Garay RP; El-Gewely R; Armstrong JK; Garratty G; Richette P Antibodies against polyethylene glycol in healthy subjects and in patients treated with PEG-conjugated agents. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012, 9, 1319–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Yang Q; Lai SK Anti-PEG immunity: Emergence, characteristics, and unaddressed questions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol 2015, 7, 655–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Povsic TJ; Lawrence MG; Lincoff AM; Mehran R; Rusconi CP; Zelenkofske SL; Huang Z; Sailstad J; Armstrong PW; Steg PG et al. Pre-existing anti-PEG antibodies are associated with severe immediate allergic reactions to pegnivacogin, a PEGylated aptamer.J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 2016, 138, 1712–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Ladd J; Zhang Z; Chen SF; Hower JC; Jiang SY Zwitterionic polymers exhibiting high resistance to nonspecific protein adsorption from human serum and plasma. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1357–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Jiang SY; Cao ZQ Ultralow-fouling, functionalizable, and hydrolyzable zwitterionic materials and their derivatives for biological applications. Adv. Mater 2010, 22, 920–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Kamaly N; Yameen B; Wu J; Farokhzad OC Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: Mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 2602–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]