In his insightful letter (1), Jeff Duyn discusses different mechanisms that might affect gradient echo MRI signal from white matter (WM) and is trying to reconcile experimental data with our recently developed theoretical model (2) as well as those of Wharton and Bowtell (3) and Sati et al (4). Duyn focuses attention mostly on anisotropic properties of myelin layers that might create a rather peculiar MR signal frequency dependence on the orientation of the external magnetic field with respect to the direction of WM fibers. The anisotropy of such a behavior was first predicted by He and Yablonskiy (5) who introduced a generalized Lorentzian approach that takes into account the effects of the structure anisotropy of WM fibers. The possibility of WM magnetic susceptibility anisotropy was then suggested by Lee et al (6) and Liu (7). A multicompartment-based theory of the influence of the anisotropic structure of myelin layers on signal frequency was proposed by Wharton and Bowtell (3) by introducing a hollow cylinder model and predicting a very interesting effect of MR signal frequency shift in the hollow (intracellular axonal) space due to the radial distribution of long lipoprotein chains in the body of the cylinder (myelin layer). A similar model was also explored by Sati et al (4) by means of numerical computer simulations.

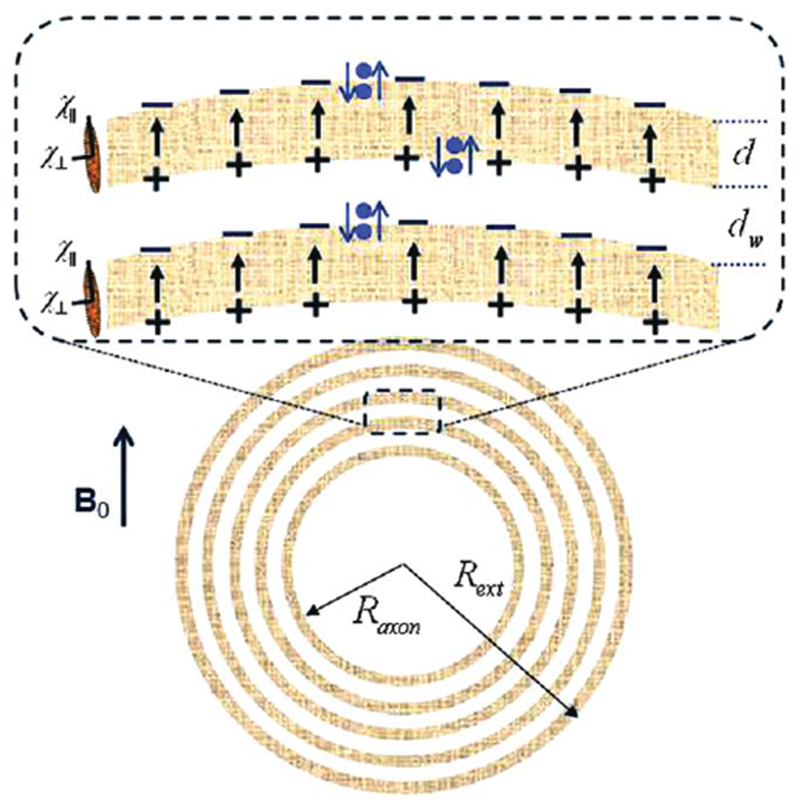

In our paper (2), we also took into account the radial distribution of long lipoprotein chains and arrived at the following expressions for the myelin-induced frequency shifts of the MR signal from the water in the axon and myelin sheath with respect to the extracellular space (see Fig. 1 and notations therein):

| [1] |

| [2] |

Here, Δχ = χ∥ − χ⊥ is the difference between longitudinal (radial) and transverse (tangential) components of magnetic susceptibility of lipoprotein chains in myelin sheath, g = Raxon/Rext, and α is the angle between the axonal and external magnetic field B0 directions.

FIG. 1.

Schematic structure of an axon with radius Raxon surrounded by a myelin sheath of the external radius Rext, consisting of lipid layers of thickness d (marked in gray) separated by aqueous phases (layers) of thickness dw. Each lipid layer is formed by highly organized, radially oriented long molecules (shown as an ellipsoids at left) with anisotropic magnetic susceptibility. In the presence of magnetic field B0, the lipid layers become magnetized and create an additional magnetic field that can be described as a result of magnetostatic charges ρ = −div M formed on the layers’ surfaces (surface charges) and inside the lipid layers (volume charges). The surface magnetostatic charges (which are of interest for the proposed “hop in, hop out” mechanism and are shown as + and − signs) are equal to ρS = ±H0 sin α ⋅ cosφ ⋅ χ∥, where α and φ are the polar and azimuthal angles (Z-direction is along the axon). The signs of the surface charges and the direction of the field H within the lipid layers correspond to χ∥ < 0. Blue dots represent water molecules performing a “Hokey Pokey”–like dance from aqueous to lipid layers. When a water molecule jumps from water layer to lipid layer, it experiences an additional field H (shown as arrows) induced by the surface charges. The projection of this field on B0 is equal to H = −H0 ⋅ χ∥ ⋅ sin2 α ⋅ cos2 φ.

One should also keep in mind a possible contribution of a water–macromolecule exchange effect proposed by Zhong et al (8). This effect was studied in detail by Luo et al (9), who demonstrated that in protein solutions, contribution of exchange effect is twice as small and of a sign opposite to that of susceptibility shifts.

In addition to the myelin-induced frequency shifts, all the compartments (axon, myelin, and extracellular) have frequency shifts due to the presence of “other” structures forming cellular matrix (eg, neurofilaments):

| [3] |

where describes magnetic susceptibility of isotropically distributed structures within the axon (a), myelin (m), and extracellular space (e), respectively. Importantly, the longitudinally arranged part of these structures is “invisible” in local frequency shifts, though it contributes to the frequency shifts outside these structures. This effect, which was predicted by He and Yablonskiy (10) and proved by computer simulations in a study by Yablonskiy et al (11), was experimentally demonstrated by Luo et al (12) in a carefully designed experiment in an optic nerve.

In this response to Dr. Duyn’s letter, we focus only on the effects created by myelin on water MR signal. The first term in Eq. [1] is similar to the result reported by Wharton and Bowtell (3). Equation 1 allows comparison with experimental data. The frequency shift (~30–35 ppb) between axonal and extracellular water signals was first measured by He and Yablonskiy (13) and Bender and Klose (14) in human brain and by He et al (15) in rat brain. Sati et al (4) reported frequency shifts of axonal water of approximately −23 ppb in human and −29 ppb in marmoset brains. Assuming Δχ = −200 ppb (16), d = 4.5 nm, dw = 2.5 nm (17), and g is in the range of 0.55–0.9 [as suggested by Duyn (1)], we get from Eq. [1] the axonal water frequency shift from −38 ppb to −7 ppb. These values are in agreement with experimental data even without considering the role of and exchange effects.

The situation is more complicated for the myelin water signal frequency shift. Indeed, Eq. [2] is substantially different from that proposed by Wharton and Bowtell (3). The problem is that in Wharton and Bowtell’s study [as well as in the study of Sati et al (4)], myelin water was assumed to be homogeneously distributed within the entire myelin sheath and the signal frequency shift was described in the framework of the Lorentzian sphere approximation—whereas in our study (2), the myelin sheath was considered in a more realistic model consisting of lipid layers separated by aqueous layers [eg, (17–19)] as illustrated in Fig. 1 in our study (2) and Fig. 1 in the current paper. The frequency shifts in Eqs. [1] and [2] were derived in our study based on the calculations of magnetic fields induced by this system in all the compartments.

If we were to assume a Lorentzian sphere approximation (for comparison with the studies of Wharton and Bowtell (3) and Sati et al (4) only), we should add the Lorentzian term

and the shape term to our Eq. [2]. In addition, the orientation-independent exchange term E was added in Wharton and Bowtell’s study. The combined result would be:

| [4] |

This expression can also be obtained by integrating the position-dependent frequency shifts provided in Table 1 in Wharton and Bowtell’s study.

There are two major differences between Eqs. [2] and [4]. First, Eq. [2] predicts no frequency shift for parallel orientation (α = 0), which is in agreement with experimental data [see Fig. 2B in Wharton and Bowtell (3) and Fig. 2b in Sati et al (4)]. At the same time, Eq. [4] [and corresponding equations in Wharton and Bowtell (3)] predict the non-zero frequency shift at α = 0

which can only be in agreement with experimental data if the exchange term compensates the susceptibility term exactly. Such a compensation that is related to two different physical mechanisms is unlikely. Besides, it is difficult to justify the Lorentzian sphere approximation (3,4) for myelin water signal, as water is located in a highly anisotropic environment of alternating lipid and aqueous layers. Second, as pointed out by Duyn (1), our Eq. [2] predicts the negative frequency shift for α = 90° (assuming Δχ < 0), whereas experimental data (3,4) suggest a positive shift. In both studies (3,4), the positive shift was explained by a reasonable assumption χ∥ < 0 in Eq. [4].

To resolve this discrepancy between experimental data and our approach, we propose a modification of our theory that is based on a simple and realistic physical mechanism described below.

Hop-in Hop-out Mechanism

In the presence of a magnetic field, the lipid layers become magnetized and create an additional magnetic field. This field can be described as a result of magnetostatic charges ρ = −div M formed on the layers’ surfaces (surface charges) and inside the lipid layers (volume charges). The volume charges are solely due to the anisotropy of magnetic susceptibility (2), whereas the surface charges exist even in the case of isotropic susceptibility. Only the surface charges (see Fig. 1) are of interest for the proposed “hop in, hop out” mechanism. The magnetic field induced by these charges is similar to the electric field of a capacitor. To experience this induced magnetic field, the water molecules do not need to delve deep into the lipid layer, because magnetostatic charges are located right on the layer’s surface; rather, the molecules simply need to perform a “Hokey Pokey”–like dance from aqueous phase to just beyond the lipid surface. A typical width of the aqueous phase between lipid layers is approximately 2.5 nm (17). Given that the water diffusion coefficient in the tissue is approximately 1 μm2/ms, it takes only about 3 ns to diffuse across this width. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that all water molecules in the aqueous space can rapidly hop in and out of the superficial areas of the lipid layers. Such rapid exchange would lead to an additional term in the myelin-associated water frequency shift:

| [5] |

where the parameter ζ defines the apparent fraction of time that a water molecule resides in the lipid layer. The coefficient ½ appears due to averaging over the azimuthal angle. By combining Eqs. [2] and [5], the total frequency shift of myelin water due to the presence of lipid layers can be presented as:

| [6] |

This equation explains both major features of myelin signal frequency shift: the absence of the shift for the fibers parallel to B0 and the positive shift in the perpendicular case. Importantly, it explains these features without requirement χ⊥ = 0 or additional exchange terms as in Eq. [4]. Even more importantly, Eq. [6] is consistent with the axial symmetry of the axonal structure.

Of course, the values of parameters entering Eq. [6] are unknown, and a variety of their combinations can match experimental data. For example, the frequency shift of +100 ppb reported by Sati et al (4) can be obtained assuming Δχ = −0.2 ppm, g = 0.7, and ζ ⋅ χ⊥ = −0.34 ppm.

In conclusion, the interesting controversy described by Duyn (1) can be explained by adding the “hop in, hop out” mechanism into our theory. The proposed modification allows explaining both of the characteristic experimental features of myelin water signal: no frequency shift for α = 0 and positive frequency shift for α = 90°.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Drs. Joseph Ackerman and Anne Cross for discussion. We also thank Dr. Jeff Duyn, who alerted us to an error in the arithmetical evaluation of Eq. [39] for frequency shift in our paper (3) that was subsequently corrected in the final publication.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: R01NS055963; Grant sponsor: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; Grant number: RG 4463A18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duyn JH. Frequency shifts in the myelin water compartment. Magn Reson Med 2014;71:1953–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sukstanskii AL, Yablonskiy DA. On the role of neuronal magnetic susceptibility and structure symmetry on gradient echo MR signal formation. Magn Reson Med 2014;71:345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wharton S, Bowtell R. Fiber orientation-dependent white matter contrast in gradient echo MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:18559–18564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sati P, van Gelderen P, Silva AC, Reich DS, Merkle H, de Zwart JA, Duyn JH. Micro-compartment specific T2* relaxation in the brain. Neuroimage 2013;77:268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He X, Yablonskiy DA. Biophysical mechanisms of phase contrast in gradient echo MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:13558–13563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J, Shmueli K, Fukunaga M, van Gelderen P, Merkle H, Silva AC, Duyn JH. Sensitivity of MRI resonance frequency to the orientation of brain tissue microstructure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:5130–5135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu CL. Susceptibility tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med 2010;63: 1471–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong K, Leupold J, von Elverfeldt D, Speck O. The molecular basis for gray and white matter contrast in phase imaging. Neuroimage 2008;40:1561–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo J, He X, d’Avignon DA, Ackerman JJH, Yablonskiy DA. Proteininduced water H-1 MR frequency shifts: contributions from magnetic susceptibility and exchange effects. J Magn Reson 2010;202: 102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He X, Yablonskiy DA. Biophysical mechanisms of phase contrast in gradient echo MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:13558–13563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yablonskiy DA, Luo J, Sukstanskii AL, Iyer A, Cross AH. Biophysical mechanisms of MRI signal frequency contrast in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:14212–14217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo J, He X, Yablonskiy DA. Magnetic susceptibility induced white matter MR signal frequency shifts-experimental comparison between Lorentzian sphere and generalized Lorentzian approaches. Magn Reson Med 2014;71:1251–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Yablonskiy DA. Quantitative BOLD: mapping of human cerebral deoxygenated blood volume and oxygen extraction fraction: default state. Magn Reson Med 2007;57:115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender B, Klose U. Cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid volume measurements in the human brain at 3T with EPI. Magn Reson Med 2009;61:834–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He X, Zhu M, Yablonskiy DA. Validation of oxygen extraction fraction measurement by qBOLD technique. Magn Reson Med 2008;60: 882–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lounila J, Ala-Korpela M, Jokisaari J, Savolainen MJ, Kesaniemi YA. Effects of orientational order and particle size on the NMR line positions of lipoproteins. Phys Rev Lett 1994;72:4049–4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min Y, Kristiansen K, Boggs JM, Husted C, Zasadzinski JA, Israelachvili J. Interaction forces and adhesion of supported myelin lipid bilayers modulated by myelin basic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:3154–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raine CS. Morphology of myelin and myelination. In: Morell P, editor. Myelin. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. p. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inouye H, Kirschner DA. Membrane interactions in nerve myelin. I. Determination of surface charge from effects of pH and ionic strength on period. Biophys J 1988;53:235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]