Abstract

Phytobezoars are a rare cause of small bowel obstruction (SBO), which consists of vegetable matter such as seeds, skins, fibres of fruit and vegetables that have solidified. We present the case of a 61-year-old man with no previous surgery who presented with central abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. An abdominal CT scan demonstrated SBO with a transition point in the left anterior abdomen. He proceeded to a laparoscopy, which revealed multiple perforations throughout the small bowel, from the proximal jejunum to the terminal ileum. Laparotomy was performed, and undigested chestnuts were milked out through the largest perforation and the perforations were oversewn. While obstruction due to phytobezoars is rare, this case demonstrates the importance of considering small bowel trauma and perforation due to phytobezoars and highlights the need for close inspection of the entire gastrointestinal tract for complications in the setting of phytobezoar-related bowel obstruction.

Keywords: general surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, surgery

Background

Phytobezoars are a rare cause of small bowel obstructions (SBOs). They are vegetable matter such as seeds, skins, fibres of fruit and vegetables that have solidified in the gut. We present a 61-year-old man who presented with SBO with multiple perforations throughout the small bowel after consuming a large quantity of chestnuts. To date, there have only been two documented cases of chestnut consumption causing SBO and one resulting in gastric perforation, none of which resulted in multiple small bowel perforations. This is the first case reported of phytobezoar causing multiple small bowel perforations and highlights the challenges in management.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 12-hour history of sudden onset central abdominal pain after eating a large quantity of chestnuts. The pain was colicky, radiated to the epigastrium and associated with nausea and vomiting. His last bowel movement was on the morning of admission. He was well prior to this and denied having any fevers, sweats, loss of appetite, weight loss or urinary symptoms. He had recently lost his dentures. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease, hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension. He had no previous abdominal surgery or endoscopy.

On physical examination, he was in mild discomfort. His observations were stable, with a regular heart rate of 80 bpm, blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg, body temperature of 35.5°C, respiratory rate of 16 and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. Abdominal examination revealed a soft abdomen which was mildly distended. He was tender at the supraumbilical and epigastric regions without guarding, percussion or rebound tenderness, and had high-pitched tinkling bowel sounds.

Investigations

All initial blood tests were within normal limits, including full blood examination, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests and lipase. D-dimer and cardiac function tests were also performed and were normal. Urinalysis was normal. Given that his symptoms did not improve despite analgesia and the physical examination findings above, the patient underwent an abdominal CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast. The CT scan (figures 1 and 2) demonstrated changes suggestive of SBO, with a transition point at the left anterior abdomen just deep to the ventral abdominal wall at the mid-small bowel, and colonic wall thickening at the distal sigmoid colon.

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan (axial view; dilated small bowel with small bowel faeces sign shown by an arrow and transition point shown by a circle).

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT scan (coronal view; arrow shows dilated small bowel and transition point).

Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of SBO was made and given that the patient had a virgin abdomen, we considered underlying processes such as small bowel tumours, congenital adhesions, Meckel’s diverticulum, internal hernia and mesenteric volvulus. However, given the history of consumption of a large amount of chestnuts, suspicion of an intraluminal bezoar causing obstruction was high.

Treatment

A nasogastric tube was inserted, and the patient was expediently taken to the operating theatre for an emergency laparoscopy. In contrast to the CT scan findings, the laparoscopy showed multilevel small bowel perforations with minimal contamination (figure 3). A small midline laparotomy was performed, which identified 10 small bowel perforations between 2 and 30 mm in size, extending from the proximal jejunum to the terminal ileum. Through the largest perforation in the mid-jejunum, small bowel content of primarily undigested chestnuts was milked out (figure 4). The small bowel perforations were oversewn with interrupted 3–0 polydioxanone sutures.

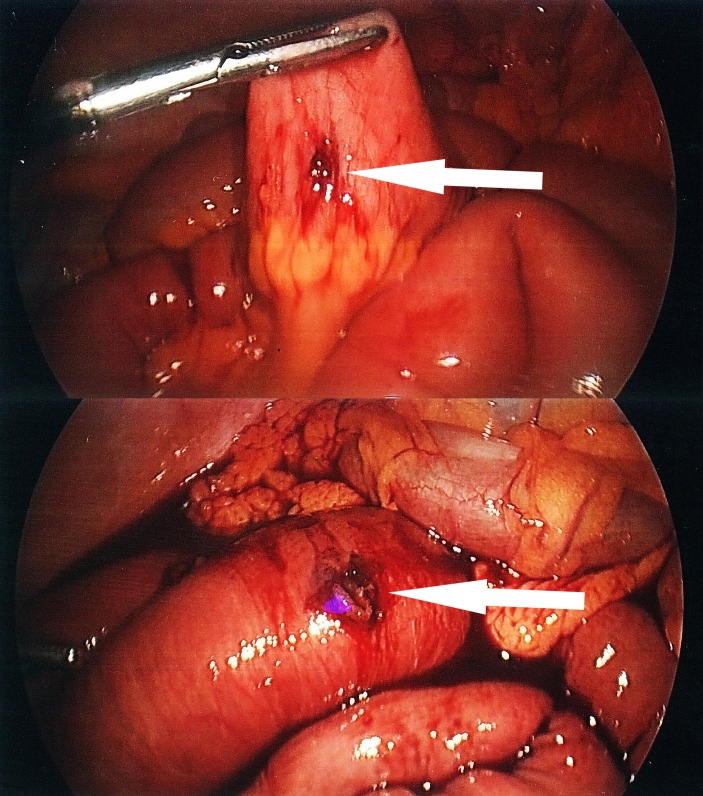

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic images of small bowel perforations.

Figure 4.

Image showing undigested chestnut expressed from the largest small bowel perforation at the mid jejunum.

Outcome and follow-up

Following the operation, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and subsequently to the surgical ward. He had prolonged hospital stay due to ileus requiring 12 days of total parenteral nutrition. He was also found to have a collection in the left paracolic gutter which was successfully drained percutaneously with CT guidance at day 19 postoperatively. He was discharged home well after a 4-week inpatient stay.

Discussion

Bezoars are a rare cause of SBO, accounting for only 0.4%–4% of all mechanical bowel obstructions. There are four types of bezoar: phytobezoars, trichobezoars, lactobezoar and pharmacobezoar. The most common type of bezoar that causes SBO is the phytobezoar, with an incidence rate of 60%.1 2 Phytobezoars are vegetable matters such as seeds, skins, fibres of fruit and vegetables that have solidified.3 Predisposing factors to bezoars include previous gastric surgery, high fibre food intake, abnormal mastication, reduced gastric secretion and motility, autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes and myotonic dystrophy.4 In this case, our patient lost his dentures and is diabetic, thus increasing his risk of bezoar formation. Bezoar SBOs commonly occur within 50–70 cm from the ileocaecal valve as the diameter of the lumen and motility decreases distally, and there is also decreased mobility of bezoars secondary to increased water absorption at the distal end.1 5

There are only a minimal number of cases whereby SBOs have been caused by chestnuts. Satake et al described a 63-year-old woman with mental retardation who presented with two episodes of SBOs almost a year apart after ingesting whole chestnuts. She required open surgery on both occasions to retrieve the intact chestnut which was impacted at the jejunum.6 Chen et al presented a 68-year-old woman with a history of pyloroplasty for a perforated peptic ulcer who had SBO secondary to a chestnut bezoar impacted at the jejunum.7 There has only been one case reported whereby a 65-year-old man presented with gastric perforation secondary to chestnut consumption.8

Multiple reports have identified previous gastric ulcer surgery as a contributing factor for bezoar formation. Dikicier et al state that surgery for ulcer treatment such as a vagotomy accompanied by a partial gastrectomy is the most significant factor in bezoar formation.9 In 2012, De Toledo et al described a case whereby a 66-year-old man with a history of diabetes and Billroth II hemigastrectomy associated with truncal vagotomy presented with a small bowel perforation 15 cm from the ileocaecal valve after excessive intake of persimmons.10 Abbas reported a 68-year-old man with SBO secondary to a phytobezoar following truncal vagotomy and gastrojejunostomy.11 Oktar et al presented a 69-year-old man with a history of Billroth II partial gastroenterostomy who presented with closed small bowel perforation with a large pouch secondary to a phytobezoar.12 There have also been cases where phytobezoars cause SBOs in patients with no significant medical history. Mortezavi et al discussed a 66-year-old man with no significant medical history who presented with SBO from an undigested whole cherry tomato.13

While bezoars are already a rare cause of mechanical SBOs, the rate of small bowel perforation due to bezoars are even less described in the current literature.12 There is only one case of multiple small bowel perforations described in 1990 by Salim whereby a 69-year-old woman presented with SBO with multiple perforations secondary to an enterolith approximately 25 cm from the ileocaecal valve.14 There were three necrotic points at the distal ileum which was resected, and an end-to-end anastomosis was performed. In our case, the 10 perforations from the chestnuts were scattered throughout the small bowel which made resection less preferable; however, they were adequately managed with primary repair and oversewing.

In terms of initial operative management, Sheikh et al presented a 60-year-old woman with diabetes with SBO secondary to phytobezoar and state that laparoscopy is a safe and effective procedure for managing the condition. While their patient did not have a perforation, they had performed the procedure laparoscopically and subsequently made a small incision in the right iliac fossa to perform an external stricturoplasty and repair.15 In our case, we had also opted to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy initially but proceeded to a minilaparotomy given the number of perforations and their location.

Interestingly, Conzo et al described a 75-year-old man who presented similarly with abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and constipation with no history of abdominal surgery.16 Preoperative imaging identified gallstone ileus as the cause of the mechanical bowel obstruction. Laparotomy showed a cholecystotransverse colon fistula, and this was managed with enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and fistula repair.

Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case reported whereby chestnut ingestion resulted in SBO with multiple perforations all throughout the length of the small bowel.

Learning points.

Phytobezoars should always be considered in patients with small bowel obstruction (SBO), especially in a virgin abdomen and if other risk factors such as prior gastric surgery or autonomic neuropathy are present.

Comprehensive history taking including recent dietary intake is important in establishing the cause of SBOs.

Early identification of small bowel perforation is essential, as patients can rapidly deteriorate, requiring intensive care unit, total parenteral nutrition and prolonged admissions.

Patient education to chew their food and have adequate hydration is advisable in this cohort.

Footnotes

Contributors: RKR: drafted, edited and finalised the manuscript; liaised with other authors and was responsible for collating the images. AD: identified the case and edited the manuscript. GLC: edited, proofread and finalised the manuscript as well as contributed in submission to the journal. ED: edited, proofread and finalised the manuscript

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1. Erzurumlu K, Malazgirt Z, Bektas A, et al. Gastrointestinal bezoars: a retrospective analysis of 34 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1813–7. 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buchholz RR, Haisten AS. Phytobezoars following gastric surgery for duodenal ulcer. Surg Clin North Am 1972;52:341–52. 10.1016/S0039-6109(16)39686-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chisholm EM, Leong HT, Chung SC, et al. Phytobezoar: an uncommon cause of small bowel obstruction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1992;74:342–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yildirim T, Yildirim S, Barutcu O, et al. Small bowel obstruction due to phytobezoar: CT diagnosis. Eur Radiol 2002;12:2659–61. 10.1007/s00330-001-1267-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koulas SG, Zikos N, Charalampous C, et al. Management of gastrointestinal bezoars: an analysis of 23 cases. Int Surg 2008;93:95–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Satake R, Chinda D, Shimoyama T, et al. Repeated small bowel obstruction caused by chestnut ingestion without the formation of phytobezoars. Intern Med 2016;55:1565–8. 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen WT, Suk FM. Abdominal pain after consuming a chestnut. Diagnosis: chestnut bezoar in the jejunum. Gastroenterology 2011;140:e9–10. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okagawa Y, Takada K, Arihara Y, et al. A case of gastric perforation caused by chestnut bezoars. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 2017;114:1830–5. 10.11405/nisshoshi.114.1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dikicier E, Altintoprak F, Ozkan OV, et al. Intestinal obstruction due to phytobezoars: an update. World J Clin Cases 2015;3:721–6. 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i8.721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Toledo AP, Rodrigues FH, Rodrigues MR, et al. Diospyrobezoar as a cause of small bowel obstruction. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2012;6:596–603. 10.1159/000343161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abbas TO. An unusual cause of gastrointestinal obstruction: bezoar. Oman Med J 2011;26:127–8. 10.5001/omj.2011.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oktar SO, Erbaş G, Yücel C, et al. Closed perforation of the small bowel secondary to a phytobezoar: imaging findings. Diagn Interv Radiol 2007;13:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mortezavi A, Schneider PM, Lurje G. An undigested cherry tomato as a rare cause of small bowel obstruction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015;97:e83–e84. 10.1308/rcsann.2015.0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salim AS. Small bowel obstruction with multiple perforations due to enterolith (bezoar) formed without gastrointestinal pathology. Postgrad Med J 1990;66:872–3. 10.1136/pgmj.66.780.872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheikh AB, Akhtar A, Nasrullah A, et al. Role of laparoscopy in the management of acute surgical abdomen secondary to Phytobezoars. Cureus 2017;9:e1363 10.7759/cureus.1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conzo G, Mauriello C, Gambardella C, et al. Gallstone ileus: one-stage surgery in an elderly patient: One-stage surgery in gallstone ileus. Int J Surg Case Rep 2013;4:316–8. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]