Abstract

Purpose of review

Genetic mosaicism is the presence of a somatic mutation in a subset of cells that differs from the inherited germline genome. Detectable genetic mosaicism is attractive as a potential early biomarker for cancer risk due to its established relationship with aging, introduction of potentially deleterious mutations, and clonal selection and expansion of mutated cells. The aim of this review is to survey shared risk factors associated with genetic mosaicism, aging and cancer risk.

Recent findings

Studies have associated aging, cigarette smoking and several genetic susceptibility loci with increased risk of acquiring genetic mosaicism. Genetic mosaicism has also been associated with numerous outcomes including cancer risk and cancer mortality; however, the level of evidence supporting these associations varies considerably.

Summary

Ample evidence exists for shared risk factors for genetic mosaicism and cancer risk as well as abundant support linking genetic mosaicism in leukocytes to hematologic malignancies. The relationship between genetic mosaicism in circulating leukocytes and solid malignancies remains an active area of research.

Keywords: genetic mosaicism, cancer risk, aging, clonal hematopoiesis, chromosomal alterations

Introduction

Human life depends on accurate maintenance of genetic material for instructions to carry out cellular growth and homeostasis. Despite high-fidelity DNA repair mechanisms, humans acquire multitudes of mutations during development, growth and aging[1]. Each individual is likely a complex mosaic of somatically acquired genetic mutations, with potentially each of the approximately 1013 cells in human body[2] containing unique mutations that differ from inherited germline DNA[3]. Previously these somatic mutations were not well characterized; however, recent advances in genotyping and sequencing technologies have enabled for unprecedented resolution for characterizing genetic mosaicism[4], allowing for detection of somatic events in a small fraction of cells and even down to the single cell level.

Genetic mosaicism, broadly defined, is the presence of a detectable clonal subset of cells that harbors a somatic mutation or mutations that are distinct from inherited germline DNA[5]. Detection of genetic mosaicism requires two fundamental features: (1) the acquisition of a somatic mutation that goes unrepaired and (2) survival and subsequent clonal expansion of the mutated cell[6]. While genetic mosaicism is likely present in all tissue types, the predominant focus of current studies has been on circulating leukocytes due to their relative ease of collection and high turnover rates. Terms such as clonal hematopoiesis (CH), age-related clonal hematopoiesis (ARCH)[7], clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP)[8], and aberrant clonal expansion (ACE)[9] have been used to describe the presence of detectable genetic mosaicism in these cells. Although clonal expansion is a necessary feature of genetic mosaicism, cytopenia or dysplastic morphology as seen in myelodysplastic syndromes is not a necessary feature of genetic mosaicism in leukocytes[8].

While aging is an established risk factor associated with genetic mosaicism, the association between detectable genetic mosaicism and cancer risk remains an active area of research. This review article surveys recent evidence on the relationship between genetic mosaicism, aging and cancer risk with the goal of identifying opportunities in which genetic mosaicism could inform etiologic knowledge of cancer or potentially serve as a predictive biomarker for identifying individuals at elevated cancer risk.

A new lens into the aging genome

The gradual erosion of the human genome with age is a well-known phenomenon that has been recognized in age-related disorders such as cancer and recently hypothesized for neurodegenerative disorders[10]. Current evidence suggests the accumulation of age-related somatic mutations in apparently healthy tissue is more frequent than anticipated[11–13]. Large, population surveys of mosaic chromosomal alterations (mCAs) indicates increasing age is robustly associated with higher population frequencies of large, structural mCAs[12–15], with current estimates of around 6–10% of individuals harboring a detectable mCA in blood or buccal-derived DNA by age 80[16, 17**]. Likewise, structural mosaicism of the sex chromosomes (e.g., female chromosome X mosaicism[18] and mosaic Y loss (mLOY)[19*–21]) is age-related and observed at higher frequencies, with detectable mLOY affecting nearly 20% of men in some elderly populations[20]. Studies of mosaic single nucleotide variants (mSNVs) further demonstrate the increase in frequency of mSNVs with increasing age[11, 22, 23]. These studies detect mSNVs in 10–15% of individuals by age 80. It is important to note that current studies of genetic mosaicism have usually focused on one type of mosaic event (e.g., only mCAs or only mSNVs) in one tissue sample and have not investigated the joint distribution of all forms of genetic mosaicism together (e.g., jointly investigating mCAs and mSNVs) across multiple tissue samples. Such combined studies will likely show higher proportions of individuals harboring at least one form of detectable genetic mosaicism in their cells and could illuminate novel interrelationships between different forms of genetic mosaicism as well as across tissue types. In addition, current population-based studies are limited in their ability to detect mutated clones that affect a small proportion of cells. These studies have limits of detection ranging from approximately 5 to 15% of cells affected, suggesting current studies are likely only observing the tip of the iceberg with respect to genetic mosaicism in apparently healthy tissue[4]. As sequencing technologies advance, sequencing depth expands and detection methods improve, more sensitive surveys of genetic mosaicism in apparently healthy tissue will likely reveal that somatic alterations are the rule rather than the exception[3].

An interesting feature of detectable genetic mosaicism is that mosaic alterations are infrequently observed in individuals under the age of 50. This seems to be the case for most forms of genetic mosaicism, including mCAs[15], mLOY[19*] and mSNVs[22, 23]. However, after 50 years of age, detected mosaic alterations rapidly increase in population frequency. Furthermore, a recent publication suggests the relationship between age and mLOY may not be a linear relationship, but rather a relationship where the population frequency of mosaicism increases exponentially with age[19*].

An outstanding question with respect to the relationship between genetic mosaicism and aging is whether mutations are acquired early in development during rapid cellular expansion and remain quiescent for years or decades before detection[6] or whether mutations are acquired with the aging process and soon after clonally expend to a detectable proportion of cells. One theory for the observed higher accumulation of clonal somatic mutations with age is the aging process may usher in new selective mechanisms that allow for clones with somatic alterations acquired years or decades beforehand, which were previously selectively neutral, to become positively selected and expand in relative frequency[3]. An alternate theory hypothesizes that genomic repair mechanisms increasingly lose efficiency with age[4]. Under this hypothesis, detected somatic mosaicism serves as fingerprints of the underlying erosion of the human genome with the aging process. The actual mechanisms leading to detectable genetic mosaicism observed in current studies is likely a combination of both processes.

Fuel for phenotypic evolution

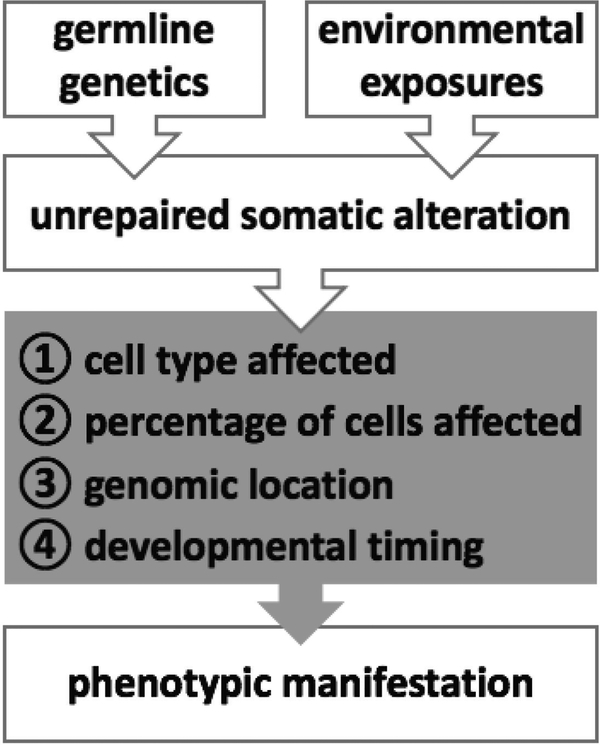

The diversity of clones introduced by genetic mosaicism and the fluid nature of these clones competing in the human body is likely important for overall health of an individual. The phenotypic manifestation of genetic mosaicism is determined by a host of features, with the predominant determinants being the cell type affected, the percentage of cells affected, the genomic location of the mutation and the developmental timing of the mutation[4, 9, 24] (Figure 1). A spectrum of mosaicism-associated phenotypic manifestations has been observed from no apparent change in phenotypic affect, to minor changes in pigmentation and nevi formation, to potentially life-threatening manifestations such as cancer[6, 24].

Figure 1.

Genetic mosaicism is due to a complex interplay of inherited susceptibility and environmental exposures. The phenotypic manifestations of a mosaic alteration vary widely depending on the underlying characteristics (gray box) of each mosaic event.

Cancer is an example of genetic mosaicism because mutated tumor DNA differs substantially from DNA of the surrounding normal tissue; but not all detected instances of genetic mosaicism is cancer related. Since cancer is a potential outcome of genetic mosaicism, studying genetic mosaicism can provide insights into cancer etiology and as well as provide clues about early manifestations of cancer. Most mSNVs are usually benign, occurring outside of protein-coding genes and have no functional consequence; however, in some cases driver mutations may occur in vital conserved functional locations of genes and could lead to substantial dysfunction of normal cellular processes and, in a short period of time, result in the onset of disease. Mosaic CNVs and large mosaic structural alterations, on the other hand, span a larger genomic footprint and as such impact a large number of genes. While an increase or decrease in gene copy number in a fraction of cells may not in and of itself be sufficient to cause disease, the changes in gene dosages over years or decades and the potential induced loss of homozygosity may manifest in phenotypic changes that favor the development of disease when further mutations are acquired.

Another form of mosaicism, referred to as revertant mosaicism, may act as a form of “purifying selection” that removes potentially deleterious inherited alleles from an individual’s genome. Revertant mosaicism occurs by acquiring mosaic alterations that in some manner correct inherited deleterious alleles, leading to functional copies of a gene. A recent example is in cases of mosaic copy number neutral loss of heterozygosity involving MPL in the UK Biobank[17**]. In instances where phase could be assigned, a variant that reduced MPL function was preferentially lost and replaced by the normal functioning allele, suggesting that mCAs removing variation that reduces MPL function can have a proliferative advantage which can lead to the recovery of normal MPL levels.

An underappreciated characteristic of genetic mosaicism is the dynamic nature in which expansion and contraction of mosaic clones occurs over time[9]. Studies of serial samples from the same mosaic individual sampled years apart indicate the percentage of circulating leukocytes with a mosaic alteration can change significantly over time[14, 15, 25]. This suggests cells affected by genetic mosaicism are in a continual state of flux where clonal expansions and contractions are common and governed by changing selective forces. Mosaicism-related imbalances in gene dosage or dysfunctional copies of a gene that expand in cellular fraction could affect a substantial proportion of cells resulting in altered tissue function, that when combined with the acquisition of further mutations could lead down a trajectory of disease pathogenesis. It is noteworthy that in some instances selective forces act against a mosaic clone and reduce the fraction of affected cells or altogether eliminate the mosaic mutation from the tissue resulting in a spontaneous reversion of genetic mosaicism back to a normal non-mutated state.

The hands of nature and nurture on genome maintenance

A key question of genetic mosaicism is the underlying forces that lead to the acquisition of mosaic alterations. Genetic mosaicism results from a complex interplay between genetic and environmental contributors that predisposes an individual to acquire mosaic alterations as well as an inability to clear these mutated cells from normal tissue. An example of studies investigating the contribution of inherited germline genetics to risk of developing genetic mosaicism is genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of mLOY, the most common observed mosaic chromosomal alteration in circulating leukocytes. An initial study identified an association with germline variation around TCL1A and increased risk of mLOY[20]. TCL1A functions as a coactivator of the cell survival kinase AKT and overexpression of this gene has been associated with development of mature T cell leukemia[26, 27]. A subsequent GWAS confirmed the association of mLOY with TCL1A and discovered 18 additional loci associated with mLOY[28**]. Many of these loci are in or near genes involved in cell cycle regulation and DNA repair as well as in cancer susceptibility genes. This evidence suggests that in some instances detectable genetic mosaicism may share molecular mechanisms important in cancer development and may serve as a proxy marker of poor inherited genomic maintenance. Larger studies are underway to further uncover associations between mLOY and inherited germline variation. GWAS of individuals with clonal hematopoiesis have also identified germline variation associated with carriers of JAK2 V617F clonal hematopoiesis[29]. In particular, germline variants in or near TERT, SH2B3, TET2, CHEK2, ATM, PINT, and GFI1B were associated with JAK2 V617F clonal hematopoiesis as well as risk of developing a myeloproliferative neoplasm. Furthermore, a recent investigation on mCAs identified 6 germline susceptibility loci that acted in cis with the nearby acquisition of mosaic deletions and of loss of heterozygosity[17**]. Identified loci include variants near MPL, TM2D3–TARSL2, and FRA10B, all for which putatively functional variants have been identified with associated high penetrance. While there is mounting evidence for an inherited predisposition to genetic mosaicism, future studies are needed to identify additional germline genetic susceptibility loci associated with risk and to determine the specific functional mechanisms of these variants that lead to increased risk of genetic mosaicism.

In addition to inherited variation, environmental exposures are key contributors to the development of genetic mosaicism. The association between aging and genetic mosaicism serves, to some extent, as a proxy for associations with genetic mosaicism and cumulative environmental exposures such as background radiation, air pollution and UV light. Recent developments in tumor sequencing studies have identified mutational signatures that are associated with mutagens such as tobacco smoke, UV light, and chemotherapeutic agents[30]. Likewise, there are reports of associations between environmental exposures and genetic mosaicism. The association between genetic mosaicism and smoking is the best characterized. Studies have observed associations between higher frequencies of mLOY and smoking across all age ranges and have noted this association attenuates with number of years of smoking cessation[19*, 20, 31]. Smoking has also been associated with increased frequency of mSNVs in clonal hematopoiesis[22]. These associations between genetic mosaicism and smoking suggests at least some forms of genetic mosaicism may be preventable. In addition to smoking, a recent study suggests air pollution also predisposes to risk of mLOY, although future studies are needed to confirm this relationship[32]. No current evidence suggests a link between alcohol consumption and genetic mosaicism[19*]. A recent sequencing study of normal skin tissue observed a surprising load of mSNVs in normal skin biopsies that closely match the UV-related mutational signature[33], suggesting UV exposure is another modifiable exposure related to increased risk of genetic mosaicism. Finally, a study of mosaic PPM1D mutations in ovarian cancer patients observed an association between chemotherapy exposure and PPM1D mutations in blood-derived DNA suggesting that chemotherapy, a vital treatment for several malignancies, may inadvertently predispose to the development of mosaicism[34]. Future studies in well characterized special exposure populations are needed for further explore and identify important environmental contributors to risk of acquiring or selecting for a genetic mosaic event.

Etiologic clues and confounders of cancer risk

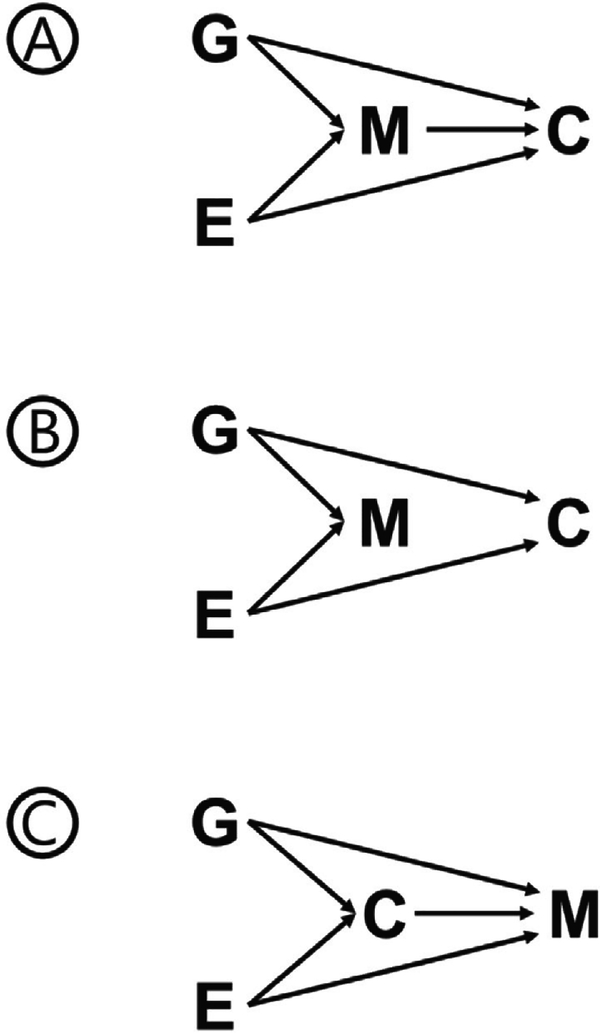

The relationship of detectable genetic mosaicism and cancer risk remains an active area of research. Varying levels of evidence suggest at least three hypothetical scenarios could potentially describe the mechanisms of action for the reported associations between genetic mosaicism and cancer risk (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Potential scenarios describing the observed associations between genetic mosaicism and cancer. (A) Intermediate: genetic mosaicism (M) is an intermediate between genetic (G) and environmental (E) contributors that mediates their effect on cancer risk (C). (B) Confounder: genetic mosaicism is associated with genetic and environmental contributors to cancer risk but is not by itself a contributor to cancer risk. (C) Reverse causation: genetic mosaicism is an outcome of genetic and environmental exposures and is also a potential outcome of cancer or cancer related treatments.

The first scenario is the relationship is causal and that studies of genetic mosaicism are detecting early, potentially preclinical aberrant cellular states that directly lead to elevated risk of cancer (Figure 2A). This is likely the case for the association between mosaicism seen in circulating leukocytes and hematologic malignancies. Studies of mCAs[12, 13, 17**] and mSNVs[22, 23] of blood-derived DNA have reported elevated risks of future hematologic malignancies. In fact, several mCAs such as mosaic 13q14 and 20q deletions overlap with common chromosome alterations seen in hematologic malignancies and can be detected as many as 15 years prior to diagnosis of a malignancy[35, 36]. This evidence suggests studies of mCAs in circulating leukocytes are detecting pre-malignant clones that may progress on to a future hematologic malignancy; although, the frequencies of these mCA events surpass the age-related prevalence of hematologic malignancies indicating that not all individuals with these mCAs will develop a leukemia. As genetic mosaicism studies expand to other tissues, similar relationships between mosaicism in these tissues and future cancer risk may be observed. A similar theory in line with this first scenario that the relationship is causal is that mCAs may also alter the ability of immune cells to identify and clear neoantigens in pre-malignant lesions in other tissues, therefore, impacting the ability of the immune system to eliminate pre-neoplastic cells or lesions that could lead to solid tumors.

A second scenario is that observed associations between genetic mosaicism and cancer may reflect confounding by shared risk factors (Figure 2B). Under this scenario genetic mosaicism is not mechanistically related to increased cancer risk but is a measure of genomic maintenance resulting from an individual’s inherited ability to maintain the genome as well as the individual’s past environmental exposure history. Two of the strongest factors associated with genetic mosaicism, aging[12, 23] and smoking[22, 31], are risk factors for several malignancies. Smoking, in particular, is difficult to get accurate self-reported measures of exposure as well as statistically model in analyses that investigate associations with genetic mosaicism[19*]. Age is also important to model correctly in statistical analyses as linear models may not completely adjust for quadratic relationships with age[19*]. Furthermore, several germline genetic susceptibility loci are shared between genetic mosaicism and cancer risk, suggesting these two conditions are potentially both outcomes of an inherited predisposition for poor genomic maintenance[20, 28**]. A failure to account for shared genetic or environmental risk factors in analyses of genetic mosaicism and cancer risk may lead to biases in analytical conclusions.

Finally, the third scenario is reverse causation in which cancer or cancer-related treatment leads to elevated levels of genetic mosaicism, rather than genetic mosaicism leading to increased cancer risk (Figure 2C). This hypothetical scenario is particularly important when examining associations in cancer case-control studies in which samples were collected post diagnosis and post treatment. A potential example of this scenario is mosaic PPM1D truncating variants and ovarian cancer in which treatment has been hypothesized to increase levels of detectable mosaicism in PPM1D[34]. Currently, it is unclear if ovarian cancer treatment increases the number of mutations that lead to mosaicism or if in some manner treatment selects for pre-existing clones with PPM1D mSNVs. While studies with samples collected after treatment may be useful for discovering potentially novel associations between genetic mosaicism and cancer risk, replication of these findings in prospective studies with samples collected at least 1–2 years prior to cancer diagnosis is essential.

Conclusion

Advances in genotyping and sequencing technologies have led to a greater awareness of the unanticipated high frequency of genetic mosaicism in normal “healthy” tissue. While recent studies have been successful at identifying contributors to and outcomes of genetic mosaicism, much remains to be learned about the initiation, clonal selection, and potential phenotypic manifestations of genetic mosaicism. As future functional studies examine the spectrum of molecular alterations resulting from genetic mosaicism, a more complete mechanistic understanding of how genetic mosaicism relates to the aging process and cancer risk will be established.

Key points.

Genetic mosaicism and cancer share several key contributing factors, including aging, smoking and shared genetic susceptibility loci.

There is a clear relationship between genetic mosaicism detected in circulating leukocytes and risk of future hematologic malignancies.

Future large efforts are needed to accurately measure and disentangle correlations between shared risk factors when assessing the relationship between genetic mosaicism in leukocyte-derived DNA and solid tumor risk.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Stephen Chanock, Meredith Yeager and Leandro Machado Colli for their critical review and substantive feedback.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 2000; 408:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianconi E, Piovesan A, Facchin F, et al. An estimation of the number of cells in the human body. Ann Hum Biol 2013; 40:463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez LC, Torres M, Real FX. Somatic mosaicism: on the road to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016; 16:43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. Detectable clonal mosaicism in the human genome. Semin Hematol 2013; 50:348–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strachan T, Read AP, Strachan T. Human molecular genetics, 4th edn. New York: Garland Science; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. The ageing genome, clonal mosaicism and chronic disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2017; 42:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlush LI. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis. Blood 2018; 131:496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2015; 126:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsberg LA, Gisselsson D, Dumanski JP. Mosaicism in health and disease - clones picking up speed. Nat Rev Genet 2017; 18:128–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank SA. Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Somatic evolutionary genomics: mutations during development cause highly variable genetic mosaicism with risk of cancer and neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107 Suppl 1:1725–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med 2014; 20:1472–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Zhou W, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism and its relationship to aging and cancer. Nat Genet 2012; 44:651–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurie CC, Laurie CA, Rice K, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism from birth to old age and its relationship to cancer. Nat Genet 2012; 44:642–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsberg LA, Rasi C, Razzaghian HR, et al. Age-related somatic structural changes in the nuclear genome of human blood cells. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machiela MJ, Zhou W, Sampson JN, et al. Characterization of large structural genetic mosaicism in human autosomes. Am J Hum Genet 2015; 96:487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vattathil S, Scheet P. Extensive Hidden Genomic Mosaicism Revealed in Normal Tissue. Am J Hum Genet 2016; 98:571–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.**.Loh PR, Genovese G, Handsaker RE, et al. Insights into clonal haematopoiesis from 8,342 mosaic chromosomal alterations. Nature 2018; 559:350–355.The largest study of autosomal mosaicism to date, showing cis relationships between germline variants and mosaic chromosomal alterations.

- 18.Machiela MJ, Zhou W, Karlins E, et al. Female chromosome X mosaicism is age-related and preferentially affects the inactivated X chromosome. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.*.Loftfield E, Zhou W, Graubard BI, et al. Predictors of mosaic chromosome Y loss and associations with mortality in the UK Biobank. Sci Rep 2018; 8:12316.Large, epidemiologic study in the UK Biobank that illustrates the importance of careful covariate adjustment when investigating associations with mosaic chromosome Y loss.

- 20.Zhou W, Machiela MJ, Freedman ND, et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y is associated with common variation near TCL1A. Nat Genet 2016; 48:563–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forsberg LA. Loss of chromosome Y (LOY) in blood cells is associated with increased risk for disease and mortality in aging men. Hum Genet 2017; 136:657–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genovese G, Kahler AK, Handsaker RE, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2477–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2488–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youssoufian H, Pyeritz RE. Mechanisms and consequences of somatic mosaicism in humans. Nat Rev Genet 2002; 3:748–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonnefond A, Skrobek B, Lobbens S, et al. Association between large detectable clonal mosaicism and type 2 diabetes with vascular complications. Nat Genet 2013; 45:1040–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virgilio L, Lazzeri C, Bichi R, et al. Deregulated expression of TCL1 causes T cell leukemia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:3885–3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laine J, Kunstle G, Obata T, et al. The protooncogene TCL1 is an Akt kinase coactivator. Mol Cell 2000; 6:395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.**.Wright DJ, Day FR, Kerrison ND, et al. Genetic variants associated with mosaic Y chromosome loss highlight cell cycle genes and overlap with cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet 2017; 49:674–679.Key genome-wide association study of mosaic chromosome Y loss demonstrating the importance of susceptivility variants in regulating cell cycle and cancer susceptibility genes.

- 29.Hinds DA, Barnholt KE, Mesa RA, et al. Germ line variants predispose to both JAK2 V617F clonal hematopoiesis and myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2016; 128:1121–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013; 500:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dumanski JP, Rasi C, Lonn M, et al. Mutagenesis. Smoking is associated with mosaic loss of chromosome Y. Science 2015; 347:81–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong JYY, Margolis HG, Machiela M, et al. Outdoor air pollution and mosaic loss of chromosome Y in older men from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Environ Int 2018; 116:239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 2015; 348:880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pharoah PDP, Song H, Dicks E, et al. PPM1D Mosaic Truncating Variants in Ovarian Cancer Cases May Be Treatment-Related Somatic Mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016; 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machiela MJ, Zhou W, Caporaso N, et al. Mosaic chromosome 20q deletions are more frequent in the aging population. Blood Adv 2017; 1:380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machiela MJ, Zhou W, Caporaso N, et al. Mosaic 13q14 deletions in peripheral leukocytes of non-hematologic cancer cases and healthy controls. J Hum Genet 2016; 61:411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]