Abstract

The brain’s astrocytes play key roles in normal and pathological brain processes. Targeting small molecules to astrocytes in the presence of the many other cell types in the brain will provide useful tools for their visualization and manipulation. Here, we explore the functional consequences of synthetic modifications to a recently described astrocyte marker composed of a bright rhodamine-based fluorophore and an astrocyte targeting moiety. We altered the nature of the targeting moiety to probe the dependence of astrocyte targeting on hydrophobicity, charge, and pKa when exposed to astrocytes and neurons isolated from the mouse cortex. We found that an overall molecular charge of +2 and a targeting moiety with a heterocyclic aromatic amine are important requirements for specific and robust astrocyte labeling. These results provide a basis for engineering astrocyte-targeted molecular tools with unique properties, including metabolite sensing or optogenetic control.

Keywords: astrocytes, cationic fluorophore, neuroimaging, brain imaging, glia imaging

Graphical Abstract

The brain requires microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes as well as myriad neuron subtypes to process information and maintain homeostasis. Among the non-neuron cell types in the brain, astrocytes have recently attracted considerable interest among neuroscientists1,2. Once thought of as being only supporters of neurons, astrocytes are now recognized as important participants in information processing3,4. For example, astrocytes can enhance or suppress neuronal signals through the delivery of gliotransmitters to the synapse5,6. They can modulate the formation and strength of neural synapses7, and experience cytosolic Ca2+ spikes upon binding neurotransmitters8, all activities once considered the purview of neurons.

Despite their long-recognized importance in maintaining neuron health, newfound attention as active circuit modulators, and distinction as the most abundant cell type in the brain9, there are relatively few strategies for targeting astrocytes. Existing targeting strategies include promoters, such as the Glial Fibrillary Acid Protein (GFAP)10, Aldh1L111, or S100B12, which can be used to express genetic reporters in astrocytes. Although these promoters are very useful for many applications, they lack applicability to systems not conducive to genetic manipulations.

Several small molecule astrocyte markers have also been reported, including the anionic fluorescent dye sulforhodamine 10113 and a coumarin di-peptide14. Sulforhodamine 101 targets astrocytes by specific uptake through an organic anion transport protein. Although it successfully labels astrocytes in rat hippocampal slice cultures15 and the mouse cortex in vivo16, it also labels oligodendrocytes, another type of glial cell in the brain, by traveling through gap junctions from labeled astrocytes17. Further, there have been no reported analogues of sulforhodamine 101 that improve its astrocyte targeting ability or alter its optical properties.

Similarly, the β-Ala-Lys-Nepsilon-Coumarin marker specifically labels primary rat astrocytes over neurons in culture14. However, this probe has been reported to have some background labeling of oligodendrocyte precursor cells14, and modifications to improve its astrocyte targeting properties are complicated by challenges associated with swapping out the coumarin fluorophore. Indeed, molecules bearing fluorescein, bodipy, or NBD as fluorophores did not function as astrocyte markers in the β-Ala-Lys-Nepsilon system14.

We recently described a class of cationic dyes that take advantage of a pendant pyridinium moiety to promote astrocyte-specific targeting via astrocyte-resident organic cation transporters18 (Figure 1A). This strategy distinguished itself from sulforhodamine 101 and β-Ala-Lys-Nepsilon-Coumarin by its broad accommodation of diverse fluorophore structures. Rhodamines, cyanines, and BODIPYs, tagged with a pyridinium moiety, produced strong labeling of primary mouse and rat astrocytes and were excluded from neurons as well as other brain-resident cells like microglia or oligodendrocyte precursor cells. This strategy extended into other vertebrate glia as well, marking GFAP-positive cells in the brains of zebrafish larvae but not neurons, other glial cell types, or other organ systems in zebrafish18.

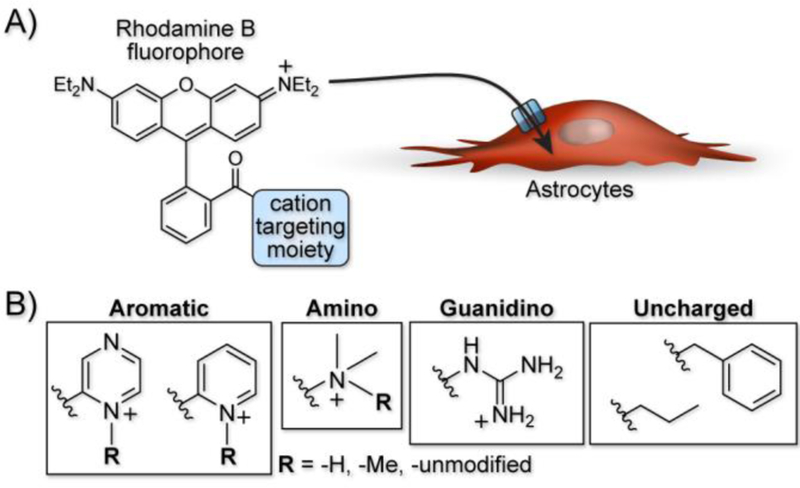

Figure 1.

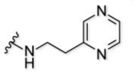

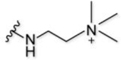

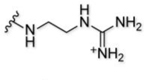

A cation targeting moiety specifically localizes fluorophores to astrocytes. A) General strategy of a rhodamine B fluorophore tagged with a cation targeting moiety for uptake through an astrocyte-resident organic cation transporter. B) Example cation targeting moieties with varying structures and charge to evaluate their dependence on astrocyte labeling.

Here, we explore the dependence of astrocyte-specific labeling with modified rhodamines on the nature of the targeting moiety (Figure 1B). Using the most successful fluorescent dye scaffold, rhodamine B, we systematically altered and tested the targeting group, exploring astrocyte labelling’s dependence on overall molecular charge and structure. Importantly, we did not explore anionic species a because model compound did not label astrocytes in a previous report18, which is expected given that the uptake mechanism relies on an organic cation transporter. The scaffolds tested are broken down into four structural classes of targeting moiety and are shown in Table 1. The first category is based on heterocyclic aromatic amines, consisting of the original methyl pyridinium (1), a methyl pyrazinium (4), the non-methylated pyridine (3) and pyrazine (5), a coupled bi-pyridinium (2), and a control non-nitrogen containing phenyl (6). The second category of compounds is amine based, consisting of a tri- and di-methylated alkyl amine (7 and 8). The third category explores labeling with a cationic alkyl guanidine (9), and the last category is composed of a simple control alkyl chain (10).

Table 1.

General synthesis scheme for library of targeting moiety scaffolds

| ||||

| Compound | Targeting molety | Yield | Pka* | Charge** |

| 1 |  |

13%‡ | n.a. | 2+ |

| 2 |  |

78% | n.a. | 3+ |

| 3 |  |

69% | 5.9 | 1+ |

| 4 |  |

62% | −5.8 | 2+ |

| 5 |  |

61% | 0.7 −5.8 |

1+ |

| 6 |  |

31% | n.a. | 1+ |

| 7 |  |

26% | n.a. | 2+ |

| 8 |  |

35% | 9.8 | 2+ |

| 9 |  |

33% | 14 | 2+ |

| 10 |  |

36% | n.a. | 1+ |

Estimated pKa based on theoretical calculations

At pH 7.4

Where possible, each class of test compounds contains functional groups with one of three key properties: (1) functional groups that are permanently positively charged (i.e., methyl pyridinium (1) and tri-methylated amine (7)); (2) functional groups with moieties whose charge is pH dependent (i.e., pyridine (3) and di-methylated amine (8)); and (3) non-ionizable functional groups (i.e., benzyl- and alkyl-modified compounds 6 and 10).

Synthesis of these compounds followed a general HATU amide coupling procedure shown in Table 1 and described in detail in Supporting Information. In brief, we bestowed each targeting moiety with a primary amine to enable coupling with the rhodamine B component. Except for the methyl pyrazinium (compound 4) and the control alkyl chain (compound 10), this strategy was successful for creating all the target compounds in yields ranging from 25 to 78%.

In the case of compound 4, we found that the 4-(2-aminoethyl) methylpyrazinium intermediate (Compound S1c, SI Scheme 1) was not stable at the basic pH required for HATU coupling. Thus, to synthesize methylpyrazinium-tagged rhodamine (compound 4), we methylated the pyrazine moiety on compound 5 after its attachment to the fluorophore with methyl iodide to provide the desired methyl pyrazinium targeting moiety in good yield of 62% (SI Scheme 2). In the case of compound 10, we followed the previous NHS-activated ester strategy that was used to synthesize compound 1, to attach the alkyl targeting moiety in a yield of 36% (SI Scheme 3).

After successful synthesis of the library, we explored astrocyte labeling, beginning with a rhodamine that possesses no targeting moiety (i.e., a free carboxylic acid). Primary mouse cortical astrocytes were bathed for 20 min at 37 °C in 1 μM of the free acid compound followed by analysis of labeling by confocal microscopy. In these experiments, lack of a targeting moiety led to minimal labeling of the astrocytes due to its net neutral molecular charge (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 1 for brightfield and individual channel images, quantified in Fig. 2B), consistent with results we observed with pyridinium-containing fluorophores bearing a net negative charge, like sulfo-cy3 and fluorescein18.

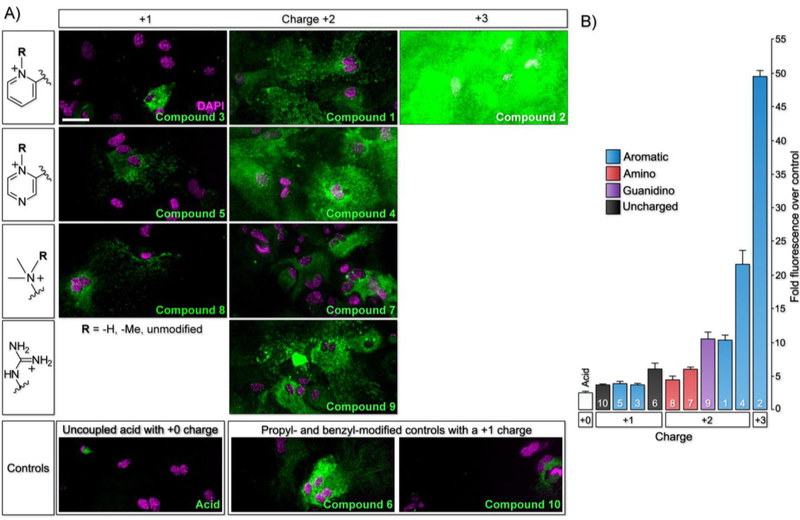

Figure 2.

Library compounds label astrocytes to varying abilities based on cation targeting moiety. A) Labeling of mouse cortical astrocytes by rhodamine B fluorophore with no targeting moiety and compounds 1 – 10. Scale bar = 25 µm. B) Measurement of mean astrocyte fluorescence for each library compound. Error bars represent SEM and n = 20.

We then bathed astrocytes with compounds 1–6 from the heterocyclic aromatic amine-based structural class, starting with the bi-pyridinium moiety that has a net +3 charge (compound 2) (SI Scheme 4). With the highest positive overall charge, we hypothesized this molecule would most readily target the organic cation transporters and robustly label astrocytes. As expected, this molecule produced the most intense astrocyte labeling (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 1), although its background adhesion to cell culture dishes was higher than most of the other compounds.

With a +2 overall charge for targeting the organic cation transporter, the methyl pyridinium (compound 1) and methyl pyrazinium (compound 4) targeting moieties strongly labeled astrocytes (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 1). Interestingly, the difference of a single nitrogen atom between the methyl pyrazinium (compound 4) and the methyl pyridinium (compound 1) targeting moiety led to a 2-fold increase in astrocyte labeling by compound 4 over the original compound 1, providing the best combination of labeling intensity and low background among the molecules tested.

After bathing with the permanently +2 charged molecules in the heterocyclic aromatic class, we moved to their non-methylated versions, pyridine (compound 3) and pyrazine (compound 5). The pyridine (compound 3) and pyrazine (compound 5) targeting moieties showed 3-fold and 5.5-fold less intense astrocyte labeling, respectively, versus their methylated counterparts (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 1). This was expected because their overall charge is dependent on their pKa, and these targeting moieties are expected to be de-protonated at physiological pH. Lastly, astrocytes bathed with the control non-nitrogen phenyl targeting moiety (compound 6) led to more intensely labeled astrocytes than either the pyridine (compound 3) or pyrazine (compound 5) targeting moieties. From the heterocyclic aromatic-based structural class, we were able to determine that a permanently, positively charged targeting moiety, giving an overall +2 molecular charge, leads to the most intense astrocyte labeling.

Moving to the alkyl-based targeting moieties, we bathed astrocytes with compound 7, containing the positively charged tri-methyl targeting moiety. Surprisingly, this compound led to minimal astrocyte labeling even though it contains a permanently, positively charged amine (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 2). In contrast, compound 9 with a guanidine targeting moiety, robustly labeled the astrocytes (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 2). Although this compound does not contain a permanent, positive charge, at physiological pH it will mostly exist in its protonated form and act as a compound with an overall +2 charge. As expected, astrocytes bathed with the di-methyl targeting moiety (compound 8) led to ~1.4-fold less intense labeling versus the tri-methyl targeting moiety (compound 9); a small difference for a large change in molecular charge (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 2). The propyl targeting moiety (compound 10) produced minimal labeling of astrocytes that was only slightly higher in intensity than the free-acid-containing compound (Fig. 2A and SI Fig. 2). From the alkyl-based structural class, we were able to confirm that a permanently, positively charged targeting moiety, giving an overall +2 molecular charge, leads to the most intense astrocyte labeling, even though the tri-methyl targeting moiety (compound 9) does not follow this general trend.

After assaying our library in astrocytes, we were interested in determining the specificity of the successful targeting moieties to astrocytes. Here, only compounds with permanently charged targeting moieties that successfully labeled astrocytes were tested in neurons. To do this, we bathed primary mouse cortical neurons for 20 min at 37 °C in 1 μM of each library compound. As expected from our previous results with the methyl pyridinium targeting moiety (compound 1), it did not label neurons (Fig. 3A and SI Fig. 3, quantified in Fig. 3B). Additionally, the structurally similar methyl pyrazinium (compound 4) also did not label neurons (Fig. 3A and SI Fig. 3). However, the trimethylamine (compound 7) and guanidine (compound 9) targeting moieties did label neurons leading us to conclude that, although these compounds label astrocytes, they lack the specificity required for an astrocyte-specific molecular probe (Fig. 3A and SI Fig. 3). When testing the control phenyl (compound 6) and propyl (compound 10) targeting moieties, we observed robust neuron labeling, leading us to believe these compounds are cell permeable (SI Fig. 4). Indeed, after bathing HEK293T cells for 20 min in 1 μM of either control compound at 37 °C, labeling was observed, confirming that these compounds are likely non-specifically taken up by many cell types (SI Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Lack of neuron labeling only visualized for heterocyclic aromatic-based compounds. A) Labeling of mouse cortical neurons with compounds 1, 2, 4, 7, and 9. Scale bar = 25 μM. B) Measurement of mean neuron fluorescence for each compound. Error bars represent SEM and n = 20.

In conclusion, astrocyte-specific molecular probes have two requirements for an organic cation transporter targeting moiety: 1) a permanent, positive charge and 2) a heterocyclic aromatic amine. Based on our results, targeting moieties with a permanent, positive charge such as a methyl pyrazinium will more readily target the astrocyte-resident organic cation transporter over a neutral moiety such as pyrazinium. Additionally, compounds from either of the heterocyclic aromatic or alkyl structural class can target astrocytes if the targeting moiety contains a positive charge. However, to guarantee specificity for astrocytes over neurons, the targeting moiety should contain heterocyclic aromatic amine, as compounds with an alkyl amine are able to label neurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Kumar, and T. Jiang for helpful discussions, B. Ruzsicska and the Stony Brook University Institute of Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery for high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis, and K. Thompson and S. Tsirka for assistance with mouse cortical astrocyte culture.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Experimental Section

For experimental details, please see supporting information.

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Ransom B; Behar T; Nedergaard M Trends Neurosci 2003, 26, 520–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haydon PG Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2001, 2, 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Araque A Neuron Glia Biol 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [4].Halassa MM; Fellin T; Haydon PG

- [5].Harada K; Kamiya T; Tsuboi T Front. Neurosci 2015, 9, 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Savtchouk I; Volterra AJ Neurosci 2018, 38, 14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chung W-S; Allen NJ; Eroglu C Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2015, 7, a020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Perea G; Navarrete M; Araque A Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ben Achour S; Pascual O Neurochem. Int 2010, 57, 440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brenner M; Kisseberth WC; Su Y; Besnard F; Messing AJ Neurosci 1994, 14, 1030–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cahoy JD; Emery B; Kaushal A; Foo LC; Zamanian JL; Christopherson KS; Xing Y; Lubischer JL; Krieg PA; Krupenko SA; Thompson WJ; Barres BA J. Neurosci 2008, 28, 264–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Raponi E; Agenes F; Delphin C; Assard N; Baudier J; Legraverend C; Deloulme J-C Glia 2007, 55, 165–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nimmerjahn A; Kirchhoff F; Kerr JND; Helmchen F Nat. Methods 2004, 1, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dieck ST; Heuer H; Ehrchen J; Otto C; Bauer K Glia 1999, 25, 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kafitz KW; Meier SD; Stephan J; Rose CR J. Neurosci. Methods 2008, 169, 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nimmerjahn A; Helmchen F Cold Spring Harb. Protoc 2012, 2012, pdb.prot068155-pdb.prot068155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [17].Hagos L; Hülsmann S Neurosci. Lett 2016, 631, 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Preston AN; Farr JD; O’Neill BK; Thompson KK; Tsirka SE; Laughlin ST ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 1493–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.