Abstract

Objective:

Improving hospital care for older people requires meaningful, valid measures of potentially preventable hospital-associated harm. The aim of this study was to propose a new multi-component measure of hospital-associated complications of older people (HAC-OP) and evaluate its validity in a large hospital sample.

Design:

Observational study using baseline (pre-intervention) data from the CHERISH cluster randomized controlled trial.

Participants:

Four hundred and thirty four patients aged 65 years or older (mean age 76 years, 48% female) with length of stay 72 hours or more on acute medical and surgical wards in four hospitals in Queensland, Australia.

Measurement:

We developed a multi-component measure including five well-recognized hospital-associated complications of older people: hospital-associated delirium, functional decline, incontinence, falls and pressure injuries. To evaluate construct validity, we examined associations with common risk factors (age over 75 years, functional impairment, cognitive impairment and history of falls). To evaluate predictive validity, we examined the association of length of stay, facility discharge and 6 month mortality with any HAC-OP, and with the total number of HAC-OP.

Results:

Overall, 192/434 (44%) of participants had one or more HAC-OP during their admission. Any HAC-OP was strongly associated with the proposed shared risk factors, and there was a strong and graded association between HAC-OP and length of stay (9.1 days [SD 7.4] for any HAC-OP vs 6.8 days [SD 4.1] with none, p<0.001), facility discharge (59/192 [31%] vs 27/242 [11%], p<0.001) and 6 month mortality (26/192 [14%] vs 17/242 [7%], p=0.02).

Conclusion:

This study provides evidence for construct and predictive validity of the proposed measure of HAC-OP as a potential outcome measure for research investigating and improving hospital care for older people.

Keywords: hospitalization, geriatric syndrome, delirium, functional decline, incontinence

INTRODUCTION

Older people admitted to hospital face the combined stress of the precipitating illness or injury, and a challenging hospital environment. Hospitalization may lead to complications which are not specific to the presenting illness, often called geriatric syndromes. Geriatric syndromes are conditions with increased prevalence in older people, multifactorial etiology, shared risk factors, and negative impact on patient outcomes1–3. Many studies reporting geriatric syndromes in hospitalized older people refer to pre-existing issues such as mobility impairment, falls history, and cognitive impairment. These have prognostic implications for older inpatients4–8 and are commonly included in comprehensive geriatric assessment. In contrast, other literature refers to new issues developing during hospitalization, such as delirium and new functional impairments. These are often iatrogenic and related to processes of care, and are therefore potential quality and safety indicators for acute care of older people, consistent with other hospital-acquired complications9.

We propose the term ‘hospital-associated complications of older people’ (HAC-OP) to distinguish new geriatric syndromes related to hospitalization. Based on literature review and clinical experience, we focused on five syndromes (delirium, functional decline, hospital-acquired incontinence, falls, and pressure injuries) which are associated with poorer outcomes (e.g., long hospital stays, more post-acute facility discharge, poorer function and higher mortality)2, 10,11 and are more common in older inpatients11–13. These complications have shared risk factors and are likely to be interdependent2,14,15. For instance, cognitive impairment is a risk factor for delirium, falls, functional decline and hospital-acquired incontinence11,15–21. Mobility impairment, falls and gait disturbance are risk factors for delirium, falls, functional decline, pressure injuries and incontinence13,15–19, while functional impairment is associated with delirium, functional decline, incontinence and pressure injuries11,13,15,19–21. Delirium prevention programs also reduce in-hospital falls22.

Trials aiming to improve hospital care of older people generally focus on a single HAC-OP as an outcome. However, in complex multi-faceted interventions, shared risk factors and interdependency may make it difficult to predict the most important outcome. Designating co-primary outcomes conventionally requires adjusted statistical significance levels, requiring increased sample size and costs. A multi-component outcome measure might help researchers and decision makers identify and maximize the potential benefits of complex interventions addressing multiple risk factors.

The aim of this paper was to evaluate the validity of a multi-component measure of HAC-OP. Using observational data from the pre-intervention phase of a multi-site intervention study in hospitalized older patients (24), we aimed to demonstrate that a multi-component measure is associated with shared risk factors for geriatric syndromes (construct validity), and has a graded exposure-response relationship with adverse outcomes (predictive validity).

METHODS

Setting, participants and assessments

We used data from the pre-intervention cohort of the CHERISH trial, a multi-site cluster randomized controlled trial of the Eat Walk Engage intervention, designed to reduce hospital-associated complications in older inpatients. The trial’s methods have been published23. In brief, during this observational phase, we enrolled consecutive consenting inpatients aged 65 years and older with length of stay 3 days or more, on eight medical or surgical wards in four hospitals October 2015 -April 2016. Patients were excluded if they were unable to be reviewed within 72 hours, discharged within 72 hours, or terminally ill. The study was approved by the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent provided by all participants or their statutory health authority.

Outcomes and measures.

Standardized comprehensive assessments were undertaken by four trained research assistants at admission, day 5, and discharge from the study ward. Self-report measures included functional status (activities of daily living [ADL]) and continence two weeks prior to admission and at each assessment; cognitive status (Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire [SPMSQ]24 and the 3 minute diagnostic interview for Confusion Assessment Method-defined delirium [3D-CAM]25) at each assessment; falls in 6 months prior to hospitalization and during hospitalization; and presence of pressure injuries at each assessment. Clinical records were reviewed using a structured abstraction tool, including demographic and disease variables; documentation of delirium26, pressure injuries or falls; length of stay under the treating team; and discharge destination, defined as usual living situation (including return to home or usual nursing home) or new facility discharge (continuing acute care, convalescent or rehabilitation care or new nursing home discharge). Death within 6 months of admission was obtained from the Queensland Health Statistics Branch.

Each HAC-OP was defined to capture complications developing during hospitalization with recognized significance for patients10,27,28. Hospital-associated functional decline was an increase in self-reported requirement for human assistance in any ADL (bathing, dressing, toileting, transfers, mobility or feeding) at hospital discharge compared to baseline function two weeks prior to admission. Hospital-associated incontinence was any self-reported urinary and/or fecal incontinence at discharge that was not present two weeks prior to admission. Hospital-associated delirium was identified either by direct assessment25 or documented in the clinical record26, excluding delirium identified within 24 hours of admission. Hospital-associated falls and pressure injuries were identified by patient report or documentation in the record, excluding pressure injuries present on admission.

The multi-component outcome ‘any HAC-OP’ was defined as presence of one or more of these five syndromes. ‘Count of HAC-OP’ (ranging from 0 to maximum of 5) was constructed to explore exposure-response effect for outcomes.

Statistical Analyses

To evaluate construct validity, we measured the association of each individual HAC-OP and any HAC-OP with four shared risk factors identified in previous studies11–21: older age (75 years or older), functional impairment (any ADL impairment at admission), cognitive impairment (admission SPMSQ under 8) and falls in the previous 6 months. Two-by-two tables were used and the odds of developing each syndrome in the presence of the risk factor calculated, using MedCalc software (https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php).

To clarify overlap between the different HAC-OP, a correlation matrix was constructed to measure within-patient associations between the complications, using Pearson’s coefficient, which indicates the direction and relative strength of correlation for binary data. Because we anticipated the complications to represent related but distinct clinical outcomes, we hypothesized a low level of correlation.

To evaluate predictive validity of the multicomponent measure, we investigated the association between HAC-OP and facility discharge and 6 month mortality using a chi-square test, and length of stay using one-way analysis of variance with log-transformation of length of stay. We examined whether there was a graded exposure-response relationship between count of HAC-OP and hospital outcomes. Analyses were made in SPSS version 22 with p<0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

We screened 2,042 older inpatients in 8 wards (general medicine, general surgery, orthopedics and respiratory medicine) between October 2015 and April 2016, of whom 862 (42%) were eligible (838 discharged within 72 hours, 183 admitted to different team/ward, 115 not screened within 72 hours, 36 terminally ill) and 474 (55%) participated (258 declined/withdrew, 112 unable to obtain consent). Discharge assessments were missing on 40 cases (8%; 9 critically ill or died, 9 declined, 22 transferred/discharged), so HAC-OP measures were calculated for 434 participants with complete data. Mean age was 76 years (SD 7), 206 (48%) were female, 18 (4%) were from nursing home, 115 (27%) had SPMSQ score less than 8, 106 (24%) were dependent in one or more ADL, and 153 (35%) reported falls in the previous 6 months. Proxy respondents were required for 31 (7%) participants.

Hospital-associated functional decline occurred in 114/434 (26%), delirium in 66 (15%), incontinence in 54 (12%), falls in 30 (7%) and pressure injuries in 18 (4%). Overall, 192/434 (44%) of participants had ‘any HAC-OP’, with 115 (26%) having one, 64 (15%) having two, and 13 (3%) having 3 or more.

Table 1 examines the association between shared risk factors and each individual HAC-OP as well as any HAC-OP. Age over 75 years increased the odds of delirium, functional decline and incontinence. Functional impairment increased odds for all syndromes. Cognitive impairment and a history of falls increased the odds of delirium, functional decline, incontinence and falls. All risk factors were significantly associated with the multi-component outcome ‘any HAC-OP’.

Table 1.

Association between each hospital-associated complication and shared risk factors, reported as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals).

| Age 75+ | Dependent ≥1 ADL at admission | SPMSQ < 8 | Falls in previous 6 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional decline (n=114) |

3.0 (1.9–4. 8) p<0.0001 |

3.5 (2.2–5.6) p<0.0001 |

2.0 (1.3–3.2) p=0.004 |

2.1 (1.4–3.3) p=0.0008 |

| Delirium (n=66) |

2.6 (1.5–4.4) p=0.0008 |

1.6 (1.0–2.7) p=0.06 |

2.9 (1.7–4.8) p<0.0001 |

1.8 (1.1–2.9) p=0.03 |

| New incontinence (n=54) |

1.7 (0.9–3.0) p=0.09 |

1.7 (0.9–3.0) p=0.08 |

2.1 (1.2–3.8) p=0.01 |

2.0 (1.1–3.6) p=0.02 |

| Fall (n=30) |

0.8 (0.4–1.7) p=0.62 |

1.4 (0.7–2.9) p=0.36 |

2.1 (1.0–4.4) p=0.04 |

2.2 (1.1–4.6) p=0.03 |

| Pressure injury (n=18) |

1.2 (0.5–2.7) p=0.68 |

1.9 (0.8–4.6) p=0.13 |

0.9 (0.4–2.4) p=0.85 |

1.1 (0.5–2.6) p=0.79 |

| Any HAC-OP (n=192) |

2.4 (1.6–3.5) p<0.0001 |

2.2 (1.5–3.3) p<0.0001 |

2.8 (1.8–4.3) p<0.0001 |

2.1 (1.4–3.2) p=0.0002 |

ADL activities of daily living; SPMSQ Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; HAC-OP hospital associated complications of older people

Table 2 shows the correlation between the five complications. There were weak although statistically significant associations between several complications: delirium was significantly associated with functional decline and falls; and functional decline was significantly associated with delirium, incontinence and pressure injuries. This pattern supports shared risk factors and/or interdependence as hypothesized, but the weak associations (correlation coefficients under 0.20) shows that these HAC-OP represent distinct domains. This means that combining them into a multi-component outcome should not exaggerate the contribution of any particular component.

Table 2:

Within-patient correlations between hospital-associated complications of older people. Cells report the Pearson correlation co-efficient (and associated p value) between each pair of complications.

| Delirium | Functional decline | New incontinence | Pressure injury | Fall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium | 1 | 0.17 (p<0.001) |

0.07 (p=0.13) |

0.01 (p=0.86) |

0.12 (p=0.01) |

| Functional decline | 0.17 (p<0.001) |

1 | 0.17 (p <0.001) |

0.14 (p=0.004) |

0.02 (p=0.63) |

| New incontinence | 0.07 (p=0.13) |

0.17 (p<0.001) |

1 | 0.08 (p=0.10) |

0.02 (p=0.68) |

| Pressure injury | 0.01 (p=0.86) |

0.14 (p=0.004) |

0.08 (p=0.10) |

1 | 0.02 (p=0.75) |

| Fall | 0.12 (p=0.01) |

0.02 (p=0.63) |

0.02 (p=0.68) |

0.02 (p=0.75) |

1 |

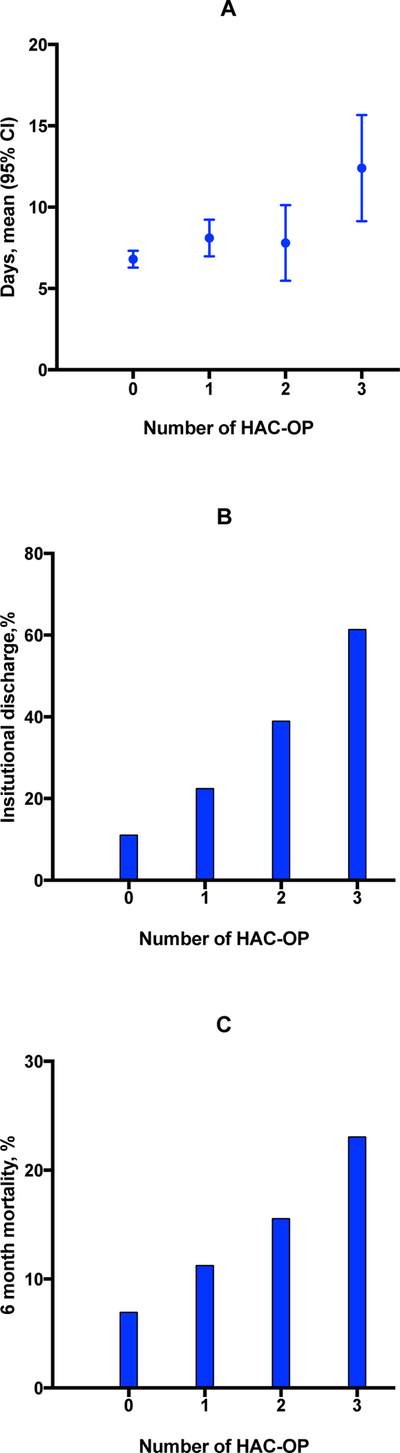

Supplementary Appendix S1 shows the association between HAC-OP and adverse outcomes. Participants with any HAC-OP had a significantly longer length of stay [mean 9.1 days (SD 7.4) vs 6.8 days (SD 4.1), p<0.001], were more likely to be discharged to a facility [59/192 (31%) vs 27/242 (11%), p<0.001], and were more likely to die within 6 months [26/192 (14%) vs 17/242 (7%), p=0.02). There was a graded and highly significant association between increasing count of HAC-OP and length of stay (p<0.001), facility discharge (p<0.001 for linear trend) and 6 month mortality (p=0.007 for linear trend) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes according to number of hospital-associated complications of older people (HAC-OP). A. Mean length of stay in days (error bars show 95% confidence intervals). B. Percentage of participants discharged to facility (continuing, rehabilitation, post-acute or new nursing home care). C. Percentage of participants who died within 6 months of admission

DISCUSSION

Using data from older inpatients admitted to eight wards, we identified several distinct hospital-associated complications prevalent in hospitalized older adults and associated with important shared risk factors. Combining these five HAC-OP provided a multi-component end-point strongly associated with the shared risk factors, and with poor outcomes. Importantly, there was a significant exposure-response effect whereby patients experiencing higher number of HAC-OP had substantially poorer outcomes in a graded fashion. Our analyses demonstrate construct and predictive validity of this proposed outcome of ‘any HAC-OP’ for use in clinical trials of complex interventions targeting shared risk factors. Advantages of this measure include higher prevalence than individual syndromes, which may make adequately powered trials more feasible, and potential to compare outcomes across different interventions.

Composite outcomes usually combine relatively uncommon events (e.g., death, myocardial infarction or revascularization) to optimize power. Identified problems include differential effects on different outcomes, competing risks, and assumptions about patient preferences for the composite outcomes29. Our proposal differs in some important respects. Firstly, the components are not rare events; however, collecting them is labor-intensive as routine screening and measurement of geriatric syndromes in clinical practice remains under-developed. Secondly, shared risk factors and interdependence make it more plausible that they will be affected to a similar extent and direction by a multicomponent intervention. Thirdly, they are outcomes recognized as important to patients as well as to the health service30; serious new functional, cognitive and continence impairments have similar disutility for seriously ill hospitalized patients28. Like other composite outcomes, we recommend reporting the individual HAC-OP and their measurement methods.

We recognize some limitations. The observed association between greater number of HAC-OP and length of stay may reflect reverse causality, i.e. those with longer stays accrued more complications. Careful time-sensitive methods would be required to explore this in more detail. The multi-component measure did not weight different components. Discharge data were missing for 40 patients (8%) who were excluded from the analysis, and consent requirements excluded some high-risk patients (e.g. those with severe illness or cognitive impairment), which may reduce generalizability of the findings. Relatively small numbers of falls and pressure injuries compared to the other HAC-OP reduce reliability of estimates for these outcomes. Misclassification of delirium as prevalent rather than incident may have underestimated the delirium outcome. The 3D-CAM was administered at admission, day 5 and discharge, and although this was supplemented with detailed chart review to improve sensitivity, some cases may have been missed. However the incidence rate is similar to rates reported in other general medical samples (11–14%)11. Prevalent delirium (with reduced SPMSQ score) might confound the associations of HAC-OP with cognitive impairment; however sensitivity analysis removing prevalent cases (n=87) did not significantly impact the strength of these associations. Strengths of our study include multiple sites, and carefully defined clinically meaningful measures including both patient reporting and record review to maximize sensitivity. This may have led to relatively high rates of complications reported, along with only sampling older patients in hospital for 3 days or more.

In summary, the concept of HAC-OP could promote greater clarity and consistency for researchers and clinicians working to understand and improve care of hospitalized older patients. Testing this outcome in trials of complex interventions targeting multiple risk factors in a variety of acute settings will inform its usefulness for researchers, clinicians, patients and families and policy-makers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix S1. Clinical outcomes (length of stay, facility discharge, and 30 day mortality) associated with each HAC-OP and the composite measure of any HAC-OP

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the CHERISH investigator team, data collection team and the staff and patients of participating wards.

Study funding: The CHERISH study is funded by a Queensland Accelerate Partnership Grant with contributions from the Queensland Government, Queensland University of Technology, and Metro North and Sunshine Coast Hospitals and Health Services. Dr Mudge was supported by a Queensland Health and Medical Research Fellowship. Dr Inouye’s time is partly supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging #R01AG044518, R24AG054259, K07AG041835, P01AG031720, and she also holds the Milton and Shirley F Levy Family Chair at Hebrew SeniorLife/Harvard Medical School.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

REFERENCES

- 1.Flacker JM. What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):574–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olde Rikkert M, Rigaud A, van Hoeyweghen R, de Graaf J. Geriatric syndromes: medical misnomer or progress in geriatrics? Neth J Med. 2003;61(3):83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J. 2008;38(1):16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang HH, Tsai SL, Chen CY, Liu WJ. Outcomes of hospitalized elderly patients with geriatric syndromes: report of a community hospital reform plan in Taiwan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50 Suppl 1:S30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flood KL, Carroll MB, Le CV, Ball L, Esker DA, Carr DB. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an oncology-acute care for elders unit. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2298–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flood KL, Rohlfing A, Le CV, Carr DB, Rich MW. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient cardiology ward. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(6):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wald HL. Prevention of hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes: applying lessons learned from infection control. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):364–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd CM. Landefeld CS, Counsell SR et al. recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56 (12):2171–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, de Rooij SE, Grypdonck MF. A systematic review of predictors and screening intruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(1):46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman S, Gorecki C, Nelson EA, et al. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development: systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(7):974–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CC, Dai YT, Yen CJ, Huang GH, Wang C. Shared risk factors for distinct geriatric syndromes in older Taiwanese inpatients. Nurs Res. 2010;59(5):340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mecocci P, von Strauss E, Cherubini A, et al. Cognitive impairment is the major risk factor for development of geriatric syndromes during hospitalization: results from the GIFA study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20(4):262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deandrea S, Bravi F, Turati F, Lucenteforte E, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(3):407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, McMurdo ME. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer MH, Baumgarten M, Langenberg P, Carson JL. Risk factors for hospital-acquired incontinence in elderly female hip fracture patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(10):M672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Saint-Hubert M, Schoevaerdts D, Poulain G, Cornette P, Swine C. Risk factors predicting later functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Acta Clin Belg. 2009;64(3):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43(3):326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watt J, Tricco AC, Talbot-Hamon C, et al. Identifying older adults at risk of delirium following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, et al. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):512–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mudge AM, Banks MD, Barnett AG, et al. CHERISH (collaboration for hospitalised elders reducing the impact of stays in hospital): protocol for a multi-site improvement program to reduce geriatric syndromes in older inpatients. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeiffer E A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in eldrly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcantonio E, Ngo L, O’Connor M, et al. 3D-CAM: Derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):554–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inouye S, Leo-Summers L, Zhang Y, Bogardus S, Leslie D, Agostini J. A chart-based method for identification of delirium: validation compared with interviewer ratings using the confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin EB, Buehler AE, Halpern SD. States worse than death among hospitalized patients with serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1557–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irony TZ. The “utility” in composite outcome measures: measuring what is important to patients. JAMA. 2017;318(18):1820–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1. Clinical outcomes (length of stay, facility discharge, and 30 day mortality) associated with each HAC-OP and the composite measure of any HAC-OP