Abstract

Purpose:

Intimate partner victimization (IPV) during the perinatal period is associated with adverse outcomes for the woman, her developing fetus, and any children in her care. Maternal mental health concerns, including depression and anxiety, are prevalent during the perinatal period particularly among women experiencing IPV. Screening and interventions for IPV targeting women seeking mental health treatment are lacking. In the current study, we examine the feasibility, acceptability, and the preliminary efficacy of a brief, motivational computer-based intervention, SURE (Strength for U in Relationship Empowerment), for perinatal women with IPV seeking mental health treatment.

Method:

The study design was a two-group, randomized controlled trial with 53 currently pregnant or within 6-months postpartum women seeking mental health treatment at a large urban hospital-based behavioral health clinic for perinatal women.

Results:

Findings support the acceptability and feasibility of the SURE across a number of domains including content, delivery, and retention. All participants (100%) found the information and resources in SURE to be helpful. Our preliminary results found the degree of IPV decreased significantly from baseline to the 4-month follow-up for the SURE condition (paired T-test, p<0.001), while the control group was essentially unchanged. Moreover, there was a significant reduction in emotional abuse for SURE participants (p=0.023) relative to participants in the control condition. There were also reductions in physical abuse although nonsignificant (p=0.060).

Conclusions:

Future work will test SURE in a larger, more diverse sample.

Keywords: Perinatal, intimate partner violence, computer intervention

Introduction

Rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) involving physical abuse within the past year prior to pregnancy are 5.3% and 3.6% during pregnancy (Chu et al. 2010). For postpartum women, research has found that rates for physical and emotional abuse within the past year are 7.4% (Certain et al. 2007). Although there is no conclusive evidence that perinatal women are at higher risk for IPV than non-perinatal women, IPV during the perinatal period presents unique challenges. In addition to health risks for the woman (Gottlieb 2008), perinatal IPV can compromise the health of the developing fetus (e.g., preterm delivery, low birthweight (Shah and Shah 2010; Sarkar 2008) and the infant (e.g., poor infant general health, difficult temperament (Burke et al. 2008), and disturbed attachment relations (Boris and Zeanah 1999)).

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support universal screening of IPV (Machisa et al. 2017). The World Health Organization (2013) recommends screening when factors known to be associated with IPV are present, such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Given the high rates of maternal mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and PTSD found among perinatal women with IPV (Cerulli et al. 2011), that a staggering 30% of patients seeking mental health treatment disclose IPV (Oram et al. 2013), and that IPV is a significant predictor of mental health symptoms, reduces the likelihood of engaging with treatment, and increases premature termination of mental health care (Johnson and Zlotnick 2007; Wilson et al. 2007; Creech et al. 2012), screening and interventions for IPV should target perinatal women seeking mental health treatment. Furthermore, untreated psychiatric disorders are associated with partner revictimization (Chang et al. 2008; Iverson et al. 2011). Thus, mental health clinics compared to other medical settings (e.g. primary care) could be more effective sites for focused case finding and intervention.

There are several obstacles that contribute to low rates of IPV screening and intervention among female patients seeking mental health treatment. For example, compared to other physicians, psychiatrists exhibit less supportive attitudes towards victims of IPV (Garimella et al. 2000), IPV training and knowledge of resources is limited among psychiatric residents (Currier et al. 1996), and 60% of mental health professionals report that they lack adequate knowledge of IPV (Nyame et al. 2013). Thus, there are much needed but inadequate systems in place for mental health clinics or providers to respond to women with IPV.

Currently, there are only three IPV-focused interventions that have demonstrated efficacy in reducing IPV by a RCT, two of which were conducted with pregnant women in the US (Kiely et al. 2010; Sharps et al. 2016) and the other in China (Tiwari et al. 2010). These studies included health care professionals and the interventions consisted of 4, 6 or 12 sessions, raising concerns regarding costs and sustainability of these interventions. Computer-delivered screening and intervention could overcome a number of barriers and may facilitate the disclosure of IPV. In a recent qualitative study of 26 perinatal women, a computer tablet was found to be a safe, confidential and non-judgmental mode of disclosing IPV (Bacchus et al. 2016). A systematic review of methods of screening for IPV found that self-administered computer screening outperformed other screening methods (Hussain et al. 2015), including face-to-face by 37%, and self-administered, paper and pencil screeners by 23%.

The purpose of the current study is to test the feasibility and acceptability of a brief computer-based intervention (Strength for U in Relationship Empowerment; SURE) for perinatal women seeking mental health treatment who report IPV risk within the past year. We also examine IPV outcomes as a preliminary evaluation of potential responses to treatment to inform future larger-scaled trials of the SURE intervention.

Methods

Participants/Procedure

Perinatal women (currently pregnant or within 6-months postpartum) seeking mental health treatment at an urban hospital-based behavioral health clinic for perinatal women were invited to a “Health Survey,” a survey to help moms have healthier pregnancies and be healthy during the postpartum period. The survey was self-administered on a Tablet PC. For safety reasons, only women who were unaccompanied while waiting for their appointment were approached by the research assistant to complete the health survey. Perinatal women who were 18 years of age or older, English-speaking, and reported experiencing IPV in the past 12 months were eligible and recruited into the study. The 8-item Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) (Brown et al. 2000) was used to screen for past year IPV (i.e., physical, sexual, and emotional abuse), and is consistent with the definition of IPV by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Brown et al. 2000). It has correctly classified 100% of non-abused women and 92% of abused women in a known-group analysis (Brown et al. 2000), has adequate psychometrics, even with minorities (Fogarty and Brown, 2002). Consistent with similar studies, IPV status was positive if a woman obtains a score of 4 or more on the WAST.

All women who met study criteria whether they chose to participate in the study or not were offered information and community resources for IPV. Eligible patients who provided informed consent were enrolled in the study. After completion of the baseline assessment, the (computer) narrator “flipped a coin” and participants were randomized into the control or SURE intervention. Participants were given gift certificates for $5.00 for participation in the screening survey and financial incentive $30 for the baseline and 4-month follow-up assessment. The Institutional Review Board of the participating hospital approved all study procedures.

Intervention Condition

SURE is a computerized intervention (30-40 minutes) delivered on a small tablet-computer and was adapted and delivered using an intervention software platform, Computerized Intervention Authoring Software (CIAS, Interva, Inc; Ondersma et al. 2005). The SURE includes a parrot avatar with a female voice that addresses the participant by name, serves as a guide and narrator for the program, and reads all content aloud, allowing low-literacy participants to complete the program. Participants completed the intervention in a private and confidential setting. Feedback from informant interviews and participants of a small open trial of SURE was used to refine SURE’s content and usability. These results are described elsewhere (Hill et al. 2015). Briefly, participants reported that the intervention was educational, interesting, and realistic.

SURE is theory-driven and consistent with motivational interviewing (MI) principles. MI has wide dissemination and demonstrated efficacy for a range of clinical problems (Burke et al. 2003) and different populations, including low-income urban women (Weir et al. 2009; Carey et al. 1997). The MI-based SURE adopts a collaborative and non-confrontational approach and emphasizes increasing participants’ awareness to successful steps towards their own well-being, an approach that is in line with the empowerment model of care for IPV. SURE presents information and education regarding types of IPV, associated risks for the woman, fetus, and offspring; potential health problems associated with relationship abuse; and risks of untreated mental health problems. The SURE emphasizes the bidirectional relationship between mental health and IPV and the narrator assessed the participant’s readiness to utilize resources (e.g., remain in mental health treatment, use IPV hotlines, talk to health care provider/support person about IPV and IPV resources). Participants had the option to create a personalized safety plan that offered tailored advice for decision-making that maximizes their safety. They were given the option of selecting from a menu of potential personal change goals (autonomy) to learn more about specific topics, such as building support for IPV, building self-esteem, safety planning for IPV, breaking up with an abusive partner, how to talk to mental health care provider about seeking IPV resources and/or managing anger towards abuser. These topics were presented as a series of empowerment videos that depicted women presenting on a topic, how they managed (or skills they used for) a specific IPV-related issue, and related positive outcome. All women in the pilot study viewed at least one of these videos, with building self-esteem being the most viewed video (47%) and then building support (46%). Women were provided with optional printouts of related materials from the intervention as a resource as well as empowerment messages reinforcing the video content.

Within one month of the baseline intervention, participants completed a telephone or in-person 10-15-minute booster session to bolster the effects of the intervention. A trained interventionist reviewed goals and motivators, identified any barriers to increasing safety behaviors and achieving goals, problem solve, provide support and resources, and reinforced empowerment concepts and skills.

Control Condition

Participants randomized to the control group also interacted with the computer software and were guided by the same narrator. The content of the control condition included watching brief segments of popular television shows and following up with questions for ratings of their preference. This control condition was matched for time and has been found to be acceptable in previous behavioral trials (Tzilos et al. 2017; Ondersma et al. 2005). There was no follow-up booster session for the control condition. Participants in both conditions received information on IPV and community resources for IPV.

Measures

All assessments consisted of self-report measures, which were computer-delivered. Demographic information included education level, employment status, income level, number of weeks of gestation or delivery date, and marital status. The following measures assessed the acceptability of the computer software and of the SURE intervention: The Satisfaction with CIAS software scale (Ondersma et al. 2005) was administered to both conditions to assess for participant satisfaction on items tapping likeability, ease of use, level of interest, and respectfulness. The 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-Revised (CSQ-8-R) was administered to assess satisfaction with the SURE intervention.

The Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) (Hegarty and Valpied 2013) was administered to assess for IPV. The CAS is a widely used, 30-item self-report of behaviors that assesses the frequency of psychological, physical, sexual, and combined severe victimization within an intimate relationship over a specified period of time (i.e., previous 3 months at baseline, and 4 months since baseline). The items are presented in a six point format requiring respondents to answer “never”, “only once”, “several times”, “monthly”, “weekly” or “daily” in a twelve month period (Hegarty et al. 2005). The CAS has demonstrated face, content, criterion, and construct validity. The scale as a whole and its 4 subscales have all demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (Hegarty and Valpied 2013).

Results

Participant flow

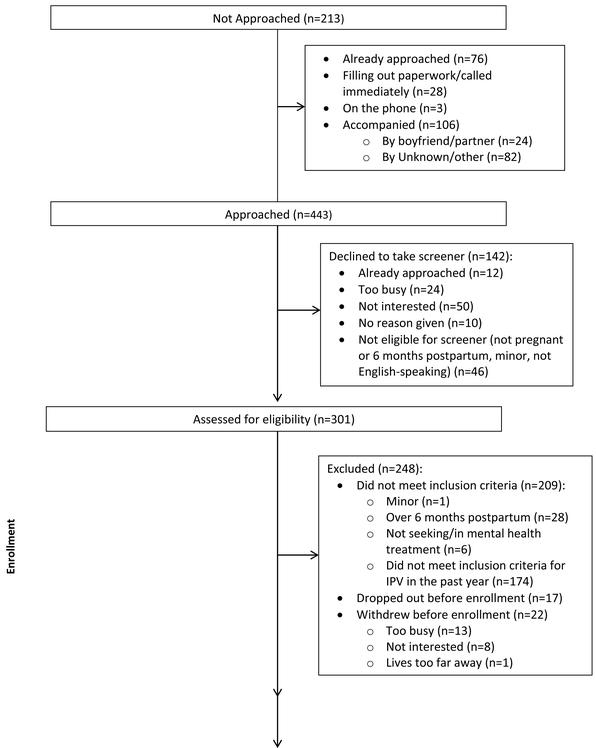

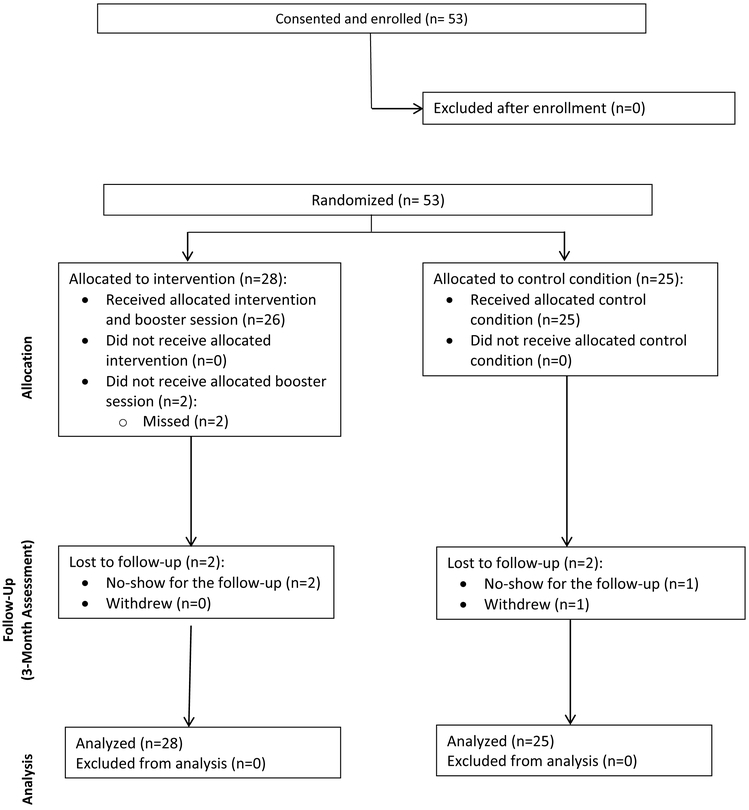

A total of 443 women were approached during recruitment for the screening phase of the study. Of those approached, 142 women (32%) declined the screener for reasons including being previously approached, too busy, not interested, or not eligible based on study criteria (see Figure 1, CONSORT diagram). An additional 213 women were not approached, the majority of which were not approached for safety reasons as they were accompanied by a partner or unknown adult. Overall, 53 women were enrolled for the randomized trial (18% of the women who were assessed for eligibility), and all 53 women (100%) completed a baseline assessment and intervention session. Of the 28 women randomized to the intervention condition, 26 (93%) completed a booster session. Forty-nine women (92%) completed the follow up assessment. Of the 28 women randomized to the intervention condition, 26 (93%) completed a follow up session. Of the 25 women randomized to the control condition, 23 (92%) completed a follow up session. One woman (2%) withdrew from the study after enrollment, and 3 women (6%) dropped out of the study and did not complete the follow up assessment. There were a total of 22 serious adverse events that were classified as unrelated to the study.

Figure 1:

CONSORT Diagram

Participant characteristics

Demographics of participants are described in Table 1. Participants enrolled in the study (N=53) were an average age of 28 years old (SD=5.3; range 18-37 years). Of the 53 women enrolled in the randomized trial, 17 women (32%) identified themselves as Hispanic/Latina. Six women (11%) identified themselves as Black or African American, 27 women (51%) identified as White, 5 (9%) identified as Bi-Racial or Multi-Ethnic, and 15 women (28%) identified as “Other”

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variable | All randomized | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=53) |

Intervention (n=28) |

Control (n=25) |

|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 27.64 (5.30) | 27.04 (5.76) | 28.32 (4.75) |

| Range | 18 – 37 | 18 – 37 | 18 – 36 |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 17 (32.08) | 8 (28.57) | 9 (36.00) |

| No | 36 (67.92) | 20 (71.43) | 16 (64.00) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian/White | 27 (50.94) | 17 (60.71) | 10 (40.00) |

| Black | 6 (11.32) | 2 (7.14) | 4 (16.00) |

| Bi-Racial | 5 (9.43) | 1 (3.57) | 4 (16.00) |

| Other | 15 (28.30) | 8 (28.57) | 7 (28.00) |

| Currently pregnant, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 22 (41.51) | 15 (53.57) | 7 (28.00) |

| No | 31 (58.49) | 13 (46.43) | 18 (72.00) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 8 (15.09) | 5 (17.86) | 3 (12.00) |

| Separated | 5 (9.43) | 2 (7.14) | 3 (12.00) |

| Divorced | 2 (3.77) | 1 (3.57) | 1 (4.00) |

| Single, no relationship | 15 (28.30) | 8 (28.57) | 7 (28.00) |

| Single, in a relationship | 21 (39.62) | 10 (35.71) | 11 (44.00) |

| Single, same-sex partner | 2 (3.77) | 2 (7.14) | 0 (0) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Didn’t graduate high school | 6 (11.32) | 4 (14.29) | 2 (8.00) |

| High school graduate | 17 (32.08) | 9 (32.14) | 8 (32.00) |

| Technical /trade school | 3 (5.66) | 2 (7.14) | 1 (4.00) |

| Some college | 17 (32.08) | 6 (21.43) | 11 (44.00) |

| College graduate | 8 (15.09) | 6 (21.43) | 2 (8.00) |

| Postgraduate | 2 (3.77) | 1 (3.57) | 1 (4.00) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Full-time | 15 (28.30) | 7 (25.00) | 8 (32.00) |

| Part-time | 9 (16.98) | 6 (21.43) | 3 (12.00) |

| Student | 3 (5.66) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.00) |

| Housewife | 10 (18.87) | 6 (21.43) | 4 (16.00) |

| Unemployed | 16 (30.19) | 9 (32.14) | 7 (28.00) |

| Any public aid, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 46 (86.79) | 24 (85.71) | 22 (88.00) |

| No | 7 (13.21) | 4 (14.29) | 3 (12.00) |

Acceptability of SURE

Participant self-reported ratings of both the computer software as well as aspects of the SURE intervention were consistently high. With regard to the overall utility of the intervention, 100% of the women reported that information and resources presented were helpful. Mean ratings of individual questions tapping satisfaction with the computer software ranged from a low of 3.2 (out of 5) to a high of 3.9. Mean ratings of the specific components of the SURE content ranged from a low of 5.7 (out of 7) (for the parrot avatar) to a high of 6.8 for the component that provided information on partner abuse and a high of 6.4 for the component on steps to increase your safety (See Table 2). With respect to the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-Revised (CSQ-8-R), the total score mean was 26.2 (SD=3.29). All women (100%) found that the SURE helped them to deal more effectively with problems, and 96% rated the quality of the SURE as excellent or good (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean ratings on satisfaction questions, N = 52

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Ratings of computer softwarea | |

| How much did you like working with the computer? | 3.48 (0.85) |

| How easy was it to use? | 3.87 (0.44) |

| How interesting was it? | 3.19 (0.89) |

| How respectful of you was it? | 3.87 (0.49) |

| How much did it bother you? | 1.35 (1.2) |

| Ratings of SURE interventionb | |

| Overall Intervention | 6.14 (1.04) |

| Videos of testimonials | 6.46 (0.74) |

| Information about women and abuse | 6.75 (0.52) |

| Information to increase safety | 6.39 (0.83) |

| Safety planning | 6.32 (0.82) |

| Ratings on Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8)c | |

| How would you rate the quality of the service you received? | 3.43 (0.57) |

| Did you get the kind of services you wanted? | 3.29 (0.60) |

| To what extent has our program met your needs? | 3.07 (0.66) |

| If a friend were in need of similar help, would you recommend our program? | 3.43 (0.57) |

| How satisfied are you with the amount of help you received? | 3.25 (0.59) |

| Have the services you received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems? | 3.25 (0.44) |

| In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the services you received? | 3.32 (0.67) |

| If you were to seek help again, would you come back to our program? | 3.14 (0.65) |

Ratings were based on a 1-5 Likert scale, where 1 = not at all, and 5 = very much

Ratings were based on a 1-7 Likert scale, where 1 = not at all helpful, and 7 = very helpful

Ratings were based on a 1-4 Likert scale, where higher scores indicate greater satisfaction

During the in-person/telephone booster session 22 women (out of 26 who completed a booster) noted that they used techniques mentioned in the intervention in working on making changes and found these techniques to be helpful (e.g., reminding themselves of their reasons for change, speaking to counselor or relative/close friend about their safety plan, reminding themselves that change is difficult but possible, etc.). Twenty-three of the 26 women reported in the booster session that they were still in counseling and 18 of those reported that they had shared aspects of the SURE intervention and their IPV experiences with their counselor. The remaining women reported that they planned to share their IPV experiences with their counselor.

IPV Outcomes

There were no significant differences between the two conditions on the IPV at risk scores (i.e., WAST scores) at screening with SURE participants obtaining a mean of 6.18 (SD = 1.79) and the control a mean score of 6.04 (SD = 2.05) (T-test p = 0.794). Total CAS victimization scores for women in the intervention condition decreased by 14.8 points at 4-month follow up assessment, which was significant (paired T-test p < 0.001), while scores for women in the control group were essentially unchanged (paired T-test p = 0.933; see Table 3). The change in total CAS scores from baseline to follow-up assessment was significant for women in the SURE condition as compared to women in the control condition (T-test p < 0.01). This change score was still significant when controlling for pregnancy status.

Table 3.

Main outcomes of Composite Abuse Scale (CAS), N = 49

| Score | Intervention | Control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N | 26 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 27.2 (18.1) | 16.8 (12.1) | 0.025 |

| Follow up | |||

| N | 26 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.4 (12.4) | 16.5 (20.2) | 0.402 |

| Change score | |||

| N | 26 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.8 (18.6) | 0.30 (17.2) | 0.007 |

| Paired T-Test | p = 0.0004 | p = 0.933 | |

| Baseline – Excluding outlier | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 25.1 (15.1) | 16.8 (12.1) | 0.043 |

| Follow up – Excluding outlier | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.9 (12.4) | 16.5 (20.2) | 0.462 |

| Change score – Excluding outlier | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.2 (13.5) | 0.30 (17.2) | 0.010 |

| Paired T-Test | p = 0.0001 | p = 0.933 | |

| Subscale Scores – Excluding outlier | |||

| Severe Combine Abuse | |||

| Baseline | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.84 (1.34) | 0.70 (1.11) | 0.833 |

| Follow up | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.28 (0.89) | 0.74 (1.36) | 0.127 |

| Change score | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.56 (1.45) | −0.04 (1.58) | 0.161 |

| Wilcoxon signed rank | p = 0.056 | p = 0.957 | |

| Physical Abuse | |||

| Baseline | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.80 (5.02) | 2.96 (4.41) | 0.511 |

| Follow up | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.28 (3.23) | 2.57 (4.61) | 0.655 |

| Change score | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.52 (3.50) | 0.39 (4.90) | 0.061 |

| Wilcoxon signed rank | p = 0.004 | p = 0.836 | |

| Emotional Abuse | |||

| Baseline | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 17.4 (10.5) | 10.3 (6.68) | 0.007 |

| Follow up | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.64 (8.92) | 10.3 (11.7) | 0.814 |

| Change score | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.80 (10.0) | −0.09 (8.67) | 0.006 |

| Paired T-Test | p = 0.0007 | p = 0.962 | |

| Harassment | |||

| Baseline | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.00 (3.12) | 2.91 (3.00) | 0.925 |

| Follow up | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.68 (2.50) | 2.87 (4.35) | 0.701 |

| Change score | |||

| N | 25 | 23 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.32 (3.35) | 0.04 (4.52) | 0.253 |

| Wilcoxon signed rank | p = 0.089 | p = 0.963 | |

NOTE: The outlier was one patient in the intervention condition with a baseline score of 79 and follow-up score of 0. All subscale change scores, except for Emotional Abuse, exhibited skewed distributions and were compared by nonparametric statistical tests.

Each subscale score of the CAS showed the same pattern of greater decrease in score (improvement) for the intervention group and nearly no change for the control as the total CAS scores. The emotional abuse subscale scores for women in the SURE condition, as compared to women in the control condition, were significantly reduced from baseline to the 4-month follow-up There was a strong trend for the SURE condition demonstrating greater changes, as compared to the control condition, in scores on the physical abuse subscale (see Table 3).

Discussion

The current study demonstrated the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a brief computer-delivered intervention, SURE, targeting IPV reduction among perinatal women who sought mental health treatment. All participants (100%) found the information and resources presented in SURE to be helpful. These high satisfaction scores are also reflected in our high completion rate of the intervention and booster session. Given the obstacles that women with IPV face, such as their abuser sabotaging access to care, resources, and support (Warshaw and Sullivan 2013), as well as their difficulty in utilizing mental health treatment (Johnson and Zlotnick 2007; Wilson et al. 2007), the high completion rate for SURE and our finding that 92% of our sample returned to complete the 4-month follow-up assessment suggests that our intervention was feasible to conduct in a mental health setting with women with IPV seeking mental health treatment.

One aim of pilot studies is to determine if the effects of treatment appear promising (Kistin and Silverstein 2015). Our results are encouraging with regard to the effect of SURE on the reduction of IPV victimization, with significant changes in scores reflecting the degree of emotional abuse over a 4-month follow up period, and a trend toward significance in scores reflecting the degree of physical abuse. The physical abuse scores contributed to the difference overall in IPV scores but by itself, the difference was not large enough to be significant. Thus the effect size for physical abuse was smaller than for emotional abuse. Since the power was too low in the current sample to detect differences between the two conditions, future studies will need a larger sample to determine if SURE significantly reduces physical abuse. The lack of significant findings for the harassment subscale may have been due to the low variability in scores, given that this subscale had only 4 items (compared to the CAS emotional abuse subscale that has 11 items). Another explanation is that unless the woman had left the relationship some items in this CAS subscale may not necessarily be considered as harassment by participants (e.g., hung around outside my house). Future studies should include a comprehensive measure of harassment by an intimate partner.

Another finding of the current study is that women randomized to the SURE had significant changes in overall IPV over a 4 month period, whereas the control group remained for the most part unchanged. Even though the present study had a relatively short follow-up period (i.e., 4 months), any reduction of IPV during the perinatal period has the potential to be significant in its impact on the health and functioning of the fetus and infant.

There are a number of strengths in the current study. Our completion and retention rates were very high – 92% of the women completed the 4-month follow up assessment – demonstrating our ability to recruit and retain a high-risk, and racially and ethnically diverse sample. Compared to US intervention studies that reduced IPV among perinatal women, participants were only modestly invested in attending the intervention or the intervention attendance was unknown. In our study, women reported high ratings of acceptability with the specific intervention components, which may have been due to the iterative design of SURE and that SURE is theoretically driven and supported by the literature. We included a well-validated and reliable outcome measure, the CAS and the use of computer-delivered assessment may have facilitated disclosure.

We also acknowledge limitations of the study. Our sample size is small (N = 53) yet adequate for a pilot feasibility trial (Rounsaville et al., 2001). Women in our sample were recruited from a hospital in the Northeast and our results may not be generalizable to all perinatal women. Our sample was also a select sample of perinatal women in that the majority of women who were not approached for the study were accompanied. It is possible that these women were with a partner who was particularly controlling and abusive. Further, 58% of the women screened reported no IPV experiences. It is unknown as to what percent of these women may have had IPV experiences and if participants in the study were representative of women with IPV seeking mental health treatment. Another limitation was that our booster session was conducted either by telephone or in person, rather than completed on the computer, which may have led to biased responses. Moreover, because our control condition did not include a booster session, we cannot be certain that the significant reduction in IPV outcomes for women in the SURE condition was not associated with the additional contact of the booster session. We did not include a measure of mental health outcomes.

While 28% of our sample endorsed being single and not currently in a relationship, the literature suggests (Kuipers et al., 2012) that these women are still at high risk for IPV victimization based on their endorsement of IPV during the past 12 months (i.e., WAST score in the screener). This places them at risk for revictimization in the future, regardless of current partner status, thus making the SURE a relevant preventive intervention.

The findings of the current pilot study are encouraging and represent the first study to develop and test an intervention specifically for perinatal women with IPV seeking mental health treatment, a vulnerable group of women. In addition, few, if any, interventions incorporate content on IPV and linkages to IPV services and resources along with mental health services. Our study is also unique in its brevity for an IPV intervention. A larger trial with a longer follow-up period is necessary in order to determine if our findings are robust and can be sustained over time. Future studies should include a cost estimate of SURE in a real-life clinical setting to inform the feasibility of disseminating and implementing it on a large scale.

Acknowledgments

Grant funding: This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) HD077358.

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) R21 HD077358 (PI: Zlotnick; Co-Is: Tzilos Wernette). The authors gratefully acknowledge the women who participated in this study, as well as the research staff at Women and Infant Hospital (Ms. Sarah Hill and Ms. Michelle Scully) for their assistance with data collection and computer programming. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02370394).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No competing financial interests exist for authors Golfo Tzilos Wernette and Christina Raker. Caron Zlotnick’s husband is a consultant for Soberlink

References

- Bacchus LJ, Bullock L, Sharps P, Burnett C, Schminkey DL, Maria Buller A, Campbell J (2016). Infusing technology into perinatal home visitation in the United States for women experiencing intimate partner violence: exploring the interpretive flexibility of an mHealth intervention. J Med Internet Res 18(11): e302 doi: 10.2196/jmir.6251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boris N, Zeanah C (1999) Disturbances and disorders of attachment in infancy. Infant Ment Health J 20:1–9 [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, Sas G (2000) Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and the WAST-Short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract 49:896–903 doi:doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M (2003) The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:843–861 doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Lee L, O’Campo P (2008) An exploration of maternal intimate partner violence experiences and infant general health and temperament. Matern Child Health J 12:172–179 doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0218-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Maisto SA, Kalichman SC, Forsyth AD, Wright EM, Johnson BT (1997) Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. J Consult Clin Psychol 65:531–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certain HE, Mueller M, Jagodzinski T, Fleming MF (2007) Intimate partner violence in postpartum women. Abstracts/Contraception 76:168 [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli C, Talbot NL, Tang W, Chaudron LH (2011) Co-occurring intimate partner violence and mental health diagnoses in perinatal women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 20:1797–1803 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Theodore AD, Martin SL, Runyan DK (2008) Psychological abuse between parents: associations with child maltreatment from a population-based sample. Child Abuse Negl 32:819–829 doi:S0145-2134(08)00131-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu SY, Goodwin MM, D'Angelo DV (2010) Physical violence against U.S. women around the time of pregnancy, 2004–2007. Am J Prev Med 38:317–322 doi: 10.1016/j.amerpre.2009.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creech S, Davis KE, Howard M, Pearlstein T, Zlotnick C (2012) Psychological/verbal abuse and utilization of mental health care in perinatal women seeking treatment for depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 15:361–365 doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0294-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier GW, Barthauer LM, Begier E, Bruce ML (1996) Training and experience of psychiatric residents in identifying domestic violence. Psychiatr Serv 47:529–530 doi: 10.1176/ps.47.5.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienemann J, Boyle E, Baker D, Resnick W, Wiederhorn N, Campbell J (2000) Intimate partner abuse among women diagnosed with depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs 21:499–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty CT, Brown JB (2002) Screening for abuse in Spanish-speaking women. J Am Board Fam Pract 15:101–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garimella R, Plichta SB, Houseman C, Garzon L (2000) Physician beliefs about victims of spouse abuse and about the physician role. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 9:405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb AS (2008) Intimate partner violence: a clinical review of screening and intervention. Womens Health (Lond) 4:529–539 doi: 10.2217/17455057.4.5.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheahan M (2005) The composite abuse scale: Further development and assessment of reliability in two clinical settings. Violence Vict 20:529–547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K, Valpied J (2013) Composite Abuse Scale Manual: Version December 2013 [Assessment Instrument] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S, Schonbrun YC, Zlotnick C (2015) Perinatal women’s interest in a brief computer-based intervention for intimate partner violence. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the New England Psychological Association, Fitchburg, MA, October, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Hussain N, Sprague S, Madden K, Hussain FN, Pindiprolu B, Bhandari M (2015) A comparison of the types of screening tool administration methods used for the detection of intimate partner violence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, &Abuse 16:60–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Gradus JL, Resick PA, Suvak MK, Smith KF, Monson CM (2011) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. J Consult Clinical Psychol 79:193–202 doi: 10.1037/a0022512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C (2007) Utilization of mental health treatment and other services in sheltered battered women. Psychiatric Services 58:1595–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlijn K, van der Knapp L, Winkel F (20012). Risk of revictimization of intimate partner violence: The role attachment, anger and violent behavior of the victim. J Fam Violence 27(1):33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely M, El-Mohandes AAE, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG (2010) An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynaecol 115:273–283 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistin C, Silverstein M (2015) Pilot studies: A critical but potentially misused component of interventional research. JAMA 314:1561–1562 doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machisa MT, Christofides N, Jewkes R (2017) Mental ill health in structural pathways to women's experiences of intimate partner violence. PLoS One 12 doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.4733020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyame S, Howard LM, Feder G, Trevillion K (2013) A survey of mental health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and preparedness to respond to domestic violence. J Ment Health 22:536–543 doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.841871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Chase SK, Svikis DS, Lee JH, Haug NA, Stitzer ML, Schuster CR (2005) Computer-based brief motivational intervention for perinatal drug use. J Subst Abuse Treat 28:305–312 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram S, Trevillion K, Feder G, Howard LM (2013) Prevalence of experiences of domestic violence among psychiatric patients: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 202:94–99 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.109934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WHO (2013) Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241548595/en/. [PubMed]

- Rounsaville B, Carroll K, & Onken L (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: getting started and moving from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice,, 8, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar NN (2008) The impact of intimate partner violence on women's reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol 28:266–271 doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PS, Shah J (2010) Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 19:2017–2031 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharps PW, Bullock LF, Campbell JC, Alhusen JL, Ghazarian SR, Bhandari SS, Schminkey DL (2016) Domestic violence enhanced perinatal home visits: The DOVE randomized clinical trial. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 25:1129–1138 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DE et al. (2017) Current Reports on Perinatal Intimate Partner Violence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19 doi:https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11920-017-0778-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2011) Domestic violence: frequently asked questions. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari AF, Salili F, Chan RY, Chan EK, Tang D (2010) Effectiveness of an empowerment intervention in abused Chinese women. Hong Kong Med J 16 Suppl 3:25–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzilos Wernette GK, Plegue M, Kahler CW, Sen A, Zlotnick C (inpress; ). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a computer-delivered brief intervention for substance use and risky sex during pregnancy J Womens Health (Larchmt) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw C, Sullivan CM (2013) A systematic review of trauma-focused interventions for domestic violence survivors. U. S. Dept. of Health & Human Services [Google Scholar]

- Weir BW et al. (2009) Reducing HIV and partner violence risk among women with criminal justice system involvement: a randomized controlled trial of two motivational interviewing-based interventions. AIDS Behav 13:509–522 doi: 10.1007/s10461-008.9422-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KS, Silberberg MR, Brown AJ, Yaggy SD (2007) Health needs and barriers to healthcare of women who have experienced intimate partner violence. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 16:1485–1498 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]