Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenide (2D TMD) layers present an unusually ideal combination of excellent opto-electrical properties and mechanical tolerance projecting high promise for a wide range of emerging applications, particularly in flexible and stretchable devices. The prerequisite for realizing such opportunities is to reliably integrate large-area 2D TMDs of well-defined dimensions on mechanically pliable materials with targeted functionalities by transferring them from rigid growth substrates. Conventional approaches to overcome this challenge have been limited as they often suffer from the non-scalable integration of 2D TMDs whose structural and chemical integrity are altered through toxic chemicals-involved processes. Herein, we report a generic and reliable strategy to achieve the layer-by-layer integration of large-area 2D TMDs and their heterostructure variations onto a variety of unconventional substrates. This new 2D layer integration method employs water only without involving any other chemicals, thus renders distinguishable advantages over conventional approaches in terms of material property preservation and integration size scalability. We have demonstrated the generality of this method by integrating a variety of 2D TMDs and their heterogeneously-assembled vertical layers on exotic substrates such as plastics and papers. Moreover, we have verified its technological versatility by demonstrating centimeter-scale 2D TMDs-based flexible photodetectors and pressure sensors which are difficult to fabricate with conventional approaches. Fundamental principles for the water-assisted spontaneous separation of 2D TMD layers are also discussed.

Introduction

In pursuit of ever-increasing technological developments in modern electronics, there exists a continued quest for exploring novel electronic materials which can outperform traditional thin film semiconductors as well as offer unprecedented functionalities absent in them. In this regard, two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenide (2D TMD) atomic layers have recently gained enormous interests owing to their near ideal combination of superior electrical and mechanical properties unattainable in any conventional materials1–10. For instance, they can tolerate significant mechanical deformation owing to unusually high in-plane strain limits - i.e. >5 times over covalently-bonded inorganic thin films - while preserving intrinsic semiconductor properties manifested by large ON/OFF current ratios demanded for modern transistors11,12. Such property advantages project unexplored opportunities in a wide range of emerging technologies, particularly in digital electronics of unconventional form factors such as wearable and stretchable devices. Moreover, heterogeneously integrating 2D TMD layers of distinguishable yet tailored components has been predicted to enable even more exotic functionalities impossible with conventional thin film semiconductor growth technologies3,13–25. As 2D TMD layers exert weak van der Waals (vdW) attraction to underlying growth substrates, it is possible to individually assemble them in a layer-by-layer manner achieving targeted electronic structures, implying new venues for 2D heterojunction devices with tailored band offsets22–26. Such atom thick semiconductor heterostructures have been technically challenging to integrate with conventional thin film growth strategies owing to their intrinsic lattice match constraint which imposes the crystallographic limitation for the choice of materials to be integrated. A few critical prerequisites exist in order to realize the aforementioned advantages inherent to 2D TMDs toward their exploration for novel technologies; (1) It is demanded to develop viable strategies to transfer 2D TMD layers from original growth substrates and integrate them on secondary substrates of targeted functionalities, e.g., mechanically flexible substrates. (2) The intrinsic mechanical and electrical properties of the transferred 2D layers should not be compromised throughout their integration process and should be uniformly preserved on a wafer scale. (3) The layer integration process should be generalized to 2D TMDs and substrates of diverse materials without being limited to specific kinds for technological versatility. Presently, the most commonly employed approach for the transfer and integration of 2D TMD layers relies on the chemical etching of underlying growth substrates involving protection polymers (e.g., polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA)) and subsequent chemical lift-off27–29. However, such strategies tend to result in the fragmentation of individual 2D layers as they employ solution-based chemicals to etch away both the protection layer and growth substrates (e.g., silicon dioxide (SiO2) or sapphire wafer)28. Accordingly, they impose scalability limitation in terms of heterogeneously stacking up 2D layers of multiple components in a controlled manner as well as being difficult to be applied to a variety of unconventional substrates. Moreover, the intrinsic material properties of 2D layers are often compromised and damaged by the employed chemicals though their transfer and integration stages.

Herein, we report a generic and reliable strategy to achieve the layer-by-layer integration of 2D TMDs of controlled morphology and component onto arbitrary substrates over a large area. The newly developed 2D layer integration method is intrinsically “green” as it employs water only without involving any other chemicals, thus is free of any chemicals-associated material degradation. We demonstrate the layer-by-layer integration of centimeter-scale (>2 cm2) uniform 2D TMDs and their heterostructures onto virtually arbitrary substrates including, papers, woods, and plastics, which is difficult to achieve with any conventional approaches. The integrated 2D TMD layers and their heterostructures well preserve their original structural and compositional integrity benefiting from the intrinsic cleanness of the water-assisted process, confirmed by extensive spectroscopy and microscopy characterization. The technological versatility of this 2D layer integration method has been demonstrated by developing large-area 2D TMDs-based flexible photodetectors and pressure sensors on plastics and papers, respectively.

Results

Procedure for water-assisted 2D layer integration

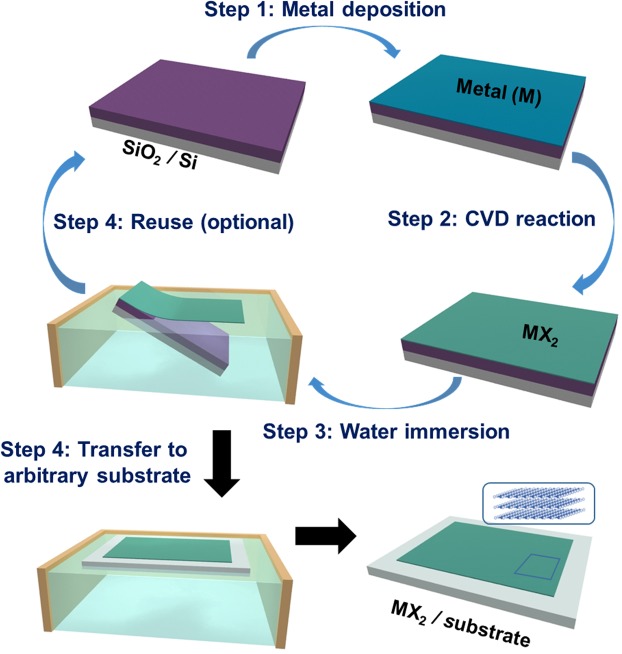

Figure 1 schematically depicts the integration of large-area 2D TMDs onto a variety of substrates via the water-assisted 2D layer transfer. The process is carried out in following steps: (1) Deposition of transition metals on the surface of growth substrates (i.e., SiO2/Si) followed by their conversion to 2D TMD layers via chemical vapor deposition (CVD). (2) Immersion of the 2D TMDs-grown SiO2/Si substrates inside water followed by spontaneous 2D layer separation. (3) Transfer and integration of the delaminated 2D TMD layers onto secondary substrates inside water. (4) Recycling of the original growth substrates for additional 2D TMDs growth (optional). Details for the CVD growth of 2D TMDs are described in Methods section. The water-assisted 2D layer separation can be carried out in following two slightly different manners. The first method is to slowly immerse the entire 2D TMDs-grown substrate inside water (See the video in Supplementary Information, S1) while the second method is to deposit water droplet only on the sample surface to leverage its buoyancy (See the video in Supplementary Information, S2). We emphasize that the whole process utilizes water only without involving any kinds of additional chemicals for the separation, transfer, and integration of 2D TMD layers. Previous approaches generally employed the combined use of polymeric protective materials (e.g., PMMA or Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)) and chemical etchants for the removal of SiO228,29. In addition to the operational complexity inherent to these conventional approaches, 2D TMDs are susceptible to chemical degradation owing to the corrosive nature of hydrogen fluoride (HF) or strong bases (sodium or potassium hydroxide (NaOH or KOH)) involved in the processes27,29. Moreover, their structural integrity can be significantly altered by the solution-based chemicals (e.g. acetone) employed to rinse away the protective polymers as well as being affected by the polymer residuals. On the other hand, our water-assisted approach yields the completely clean and homogenous integration of a variety of 2D TMDs on a large centimeter scale (to be demonstrated below). As this approach is intrinsically free of introducing chemicals-associated structural damage, the original SiO2/Si substrates after 2D layer separation can be reused for the subsequent growth of additional 2D TMD materials (step (4) in Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic to illustrate the water-assisted green integration of CVD-grown 2D TMD layers on arbitrary substrates.

Demonstration of water-assisted 2D layer transfer and integration

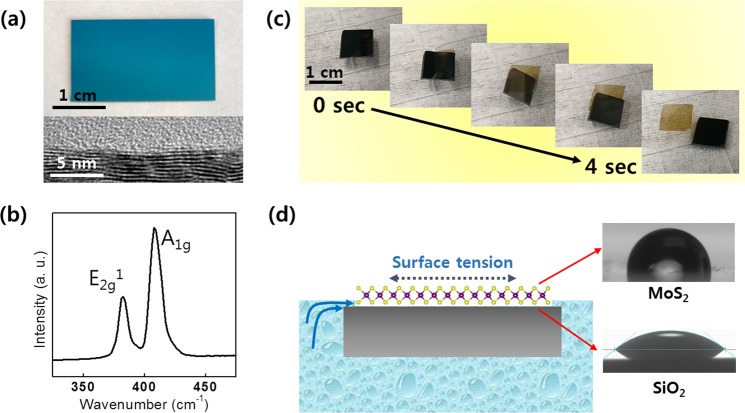

Figure 2 is the experimental demonstration of the water-assisted 2D TMD layer transfer and integration utilizing 2D molybdenum disulfide (2D MoS2) as a representative case. Figure 2(a) shows the representative images of as-grown 2D MoS2 layers on SiO2/Si on a dimension of ~ 2 × 3 cm2 (top image). In optimizing 2D MoS2 layers growth conditions, we have considered the previous studies which report the transition of horizontal-to-vertical 2D layer orientation in the CVD thermal sulfurization of Mo30–32. In order to ensure the growth of horizontally-oriented layers only, we have typically deposited Mo of small and uniform thickness (<3 nm) and carried out the CVD sulfurization using the previously developed recipe33–35. The cross-sectional transmission electron microscope (TEM) characterization (bottom image) of the same sample represents well resolved, all horizontally-oriented 2D MoS2 layers. Figure 2(b) shows the Raman spectroscopy characterization of the same sample, revealing two distinguishable peaks corresponding to their in-plane and out-of-plane E12g and A1g oscillation modes36,37. Figure 2(c) shows the time-lapsed representative images to demonstrate the sequential delamination of 2D MoS2 layers inside water recorded for ~4 sec (corresponding to the video in Supplementary Information, S2). As shown in the images, 2D MoS2 layers become spontaneously separated from the underlying SiO2/Si substrate and subsequently float on the water surface maintaining their original size and shape. The success of this facile water-assisted delamination of 2D layers is attributed to the surface energy imbalance between 2D MoS2 basal planes and SiO2 surfaces, as depicted in Fig. 2(d). Upon exposure to water droplet, our CVD-grown 2D MoS2 layers exhibit significantly larger hydrophobicity compared to the underlying SiO2, as demonstrated by the water contact angle measurement results. The observation is consistent with the previous studies on the surface wettability of 2D MoS2 layers exposing their basal planes for water adsorption38–40. Accordingly, upon the onset of water penetration into any opened interfaces of 2D MoS2/SiO2, mechanical tension is to occur and propagate underneath the weakly vdW-bound 2D basal planes. In other words, the distinct surface wettability of 2D MoS2 vs. SiO2 indicates a strong tendency for water repulsion from 2D MoS2 vs. water attraction to SiO2, respectively27,41,42. Moreover, it has been well known that the surface energy of 2D MoS2 layers is also sensitive to air exposure and its duration period. 2D MoS2 layers exhibit more pronounced hydrophobicity after elongated air exposure, confirmed by the water contact angle measurements in various studies40,43,44. In fact, we note that our CVD-grown 2D MoS2 layers also tend to become more easily separable inside water once they were exposed in air for a few days after growth. Such enhanced hydrophobicity in slightly aged 2D MoS2 layers has been attributed to a few factors, e.g., accumulation of hydrocarbons on their surface obtained from ambient air43,45. More detailed discussion regarding the influence of the surface properties of 2D MoS2 layers on the efficacy of water-assisted spontaneous layer separation is presented in the Discussion section.

Figure 2.

(a) Image of 2D MoS2 layers as-grown on SiO2/Si and the corresponding cross-sectional HRTEM image. (b) Raman spectrum obtained from the 2D MoS2 layers denoting their characteristic peaks. (c) Time-lapsed snapshot images to demonstrate the water-assisted spontaneous separation of 2D MoS2 layers inside water. (d) Illustration of the water penetration process at the 2D MoS2/SiO2 interface along with the representative images of water contact angle measurements for 2D MoS2 layers and SiO2.

Layer-by-layer integration of various 2D TMDs onto unconventional substrates

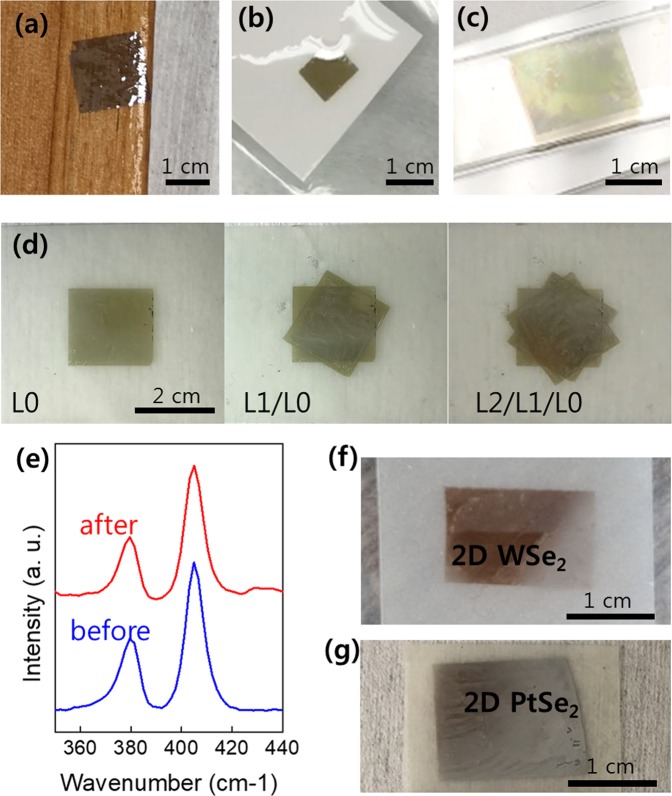

Figure 3 shows the successful demonstration of the water-assisted integration of 2D TMDs onto a variety of unconventional substrates which would be difficult to achieve otherwise. Figure 3(a–c) shows the images of centimeter-scale 2D MoS2 layers integrated on a piece of (a) wood, (b) paper, and (c) cured polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), respectively. The results highlight the strength and generality of our water-assisted integration approach which is insensitive to the kind of acceptor substrates as the entire process is chemically benign. Figure 3(d) demonstrates the “layer-by-layer” integration of 2D MoS2 layers on a piece of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate achieved over an area of ~2 cm2. After the initial integration of original 2D MoS2 layers (denoted, L0), additional layers prepared from the identical substrate were subsequently stacked on them, denoted as (L1) and (L2), solely via the water-assisted layer transfer. Details for the sequential procedures of this layer-by-layer integration are presented in Supplementary Information, S3. Figure 3(e) compares the Raman spectroscopy profiles of the corresponding sample, L0, before (blue) and after (red) its transfer from the original SiO2/Si growth substrate. It is evident that the 2D MoS2 layers integrated on PET exhibit Raman characteristics highly comparable to those obtained from their as-grown state. The result evidences the well-retained structural and chemical integrity of 2D MoS2 layers even integrated on exotic substrates, strongly emphasizing the high reliability, versatility, and cleanness of the water-assisted transfer method. Moreover, we demonstrate the generality of this layer transfer approach by extending it to a variety of 2D TMDs beyond MoS2, including 2D tungsten (W) or platinum (P) diselenides (2D WSe2 and 2D PtSe2). Figure 3(f,g) show the images of centimeter-scale CVD-grown 2D WSe2 and 2D PtSe2 layers transferred and integrated on PET substrates, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a–c) Demonstration of the water-assisted integration of 2D MoS2 layers onto a variety of unconventional substrates, including (a) wood, (b) paper, and (c) PDMS. (d) Demonstration of the layer-by-layer integration of 2D MoS2 layers onto a PET substrate. (e) Raman spectra obtained from 2D MoS2 layers before and after their water-assisted transfer. (f,g) Integration of 2D WSe2 layers (f) and and 2D PtSe2 layers (g) onto PET substrates.

Integration of vertically-stacked heterogeneous 2D TMD layers

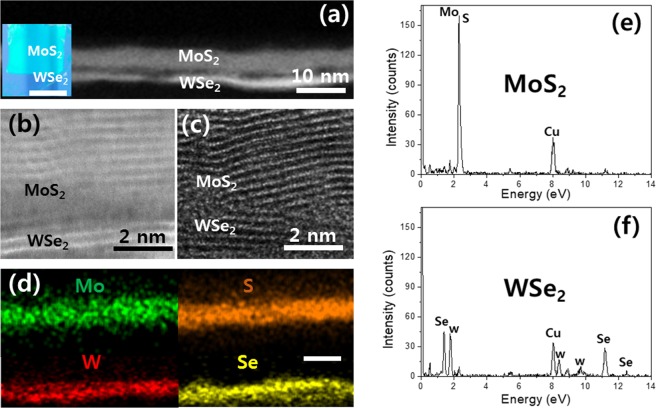

In addition to the demonstration of single-component 2D layer integration, the water-assisted transfer approach can be utilized to fabricate large-area 2D TMD vertical hetero-stacks composed of mixed chemical components, which are difficult to achieve otherwise. Most of the previously developed CVD-grown 2D TMD vertical hetero-stacks share chalcogen anions in each layer, e.g., S in 2D MoS2/WS246–49 or Se in 2D MoSe2/WSe250–52 while their lateral sizes are generally limited to nano-to-micrometer dimensions48–52. It has been difficult to grow large-area 2D TMD vertical hetero-stacks composed of “mixed” cation/anion components (e.g., 2D MoS2/WSe2) with conventional CVD approaches. The major limitation stems from that the conventional methods employ the sequential growth of one material (e.g., 2D MoS2) on top of the other (e.g., 2D WSe2) via step-wise selenization/sulfurization, which often introduces undesired thermal degradation in the pre-grown layers. For example, it has been known that the sequential thermal sulfurization of pre-grown selenides-based 2D TMDs (e.g., MoSe2 or WSe2) leads to their spontaneous conversion to sulfides-based ones (e.g., MoS2 or WS2) instead of retaining the original stoichiometry53,54. Motivated by this challenge, we explored large-area 2D/2D vertical hetero-stacks of “mixed” cation/anion components, i.e., 2D MoS2/WSe2, by integrating 2D MoS2 layers on top of pre-grown 2D WSe2 layers by applying the water-assisted layer transfer. The structural and chemical quality of the 2D MoS2/WSe2 vertical hetero-stacks was assessed by extensive TEM characterization. The cross-sectional annular dark-field (ADF) scanning TEM (STEM) image in Fig. 4(a) reveals the interfacial morphology of 2D MoS2/WSe2 vertical hetero-stacks (inset) prepared by integrating 2D MoS2 layers on top of pre-grown 2D WSe2 layers. Each sample of 2D MoS2 layers and 2D WSe2 layers was prepared by the CVD sulfurization of Mo (thickness ~2.5 nm) and selenization of W (thickness ~1 nm), respectively. The distinguishable ADF STEM image contrast across the interface indicates the atomic mass (Z-contrast) difference of the constituent materials in each stack region. The enlarged views of the 2D MoS2/WSe2 hetero-interface are provided in ADF-STEM (Fig. 4(b)) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images (Fig. 4(c)). Both the images clearly reveal that 2D layers are vertically-stacked in a layer-by-layer manner with well-resolved vdW gaps. The brighter image contrast for the bottom stack (WSe2) over the top one (MoS2) in ADF-STEM reflects the heavier mass of W over Mo. The chemical compositions of the 2D MoS2/WSe2 vertical hetero-stacks were characterized by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)-STEM (Fig. 4(d–f)). Figure 4(d) shows EDS elemental map images of the corresponding hetero-interface, revealing the spatial distribution of constituent atomic elements, Mo, W, S, and Se. The images confirm the spatially and chemically localized presence of 2D MoS2 and 2D WSe2, consistent with the observation in ADF-STEM. Figure 4(e,f) show the EDS spectrum profiles separately collected from each 2D MoS2 and 2D WSe2 stack, respectively. The results indeed confirm the stoichiometric presence of 2D MoS2 and 2D WSe2 in each vertical stack, consistent with all other TEM characterization results. It is worth mentioning that the EDS profiles do not exhibit additional peaks from any unintentionally introduced elements excepts for the Cu peaks which are from the TEM grid, further supporting the intrinsic cleanness of our water-assisted layer transfer process.

Figure 4.

(a) Cross-sectional ADF STEM image of a 2D MoS2/WSe2 hetero vertical-stack. The inset shows the corresponding sample where 2D MoS2 layers were integrated on top of 2D WSe2 layers. The scale bar is 1 cm. (b,c) High-resolution ADF-STEM (b) and TEM (c) images of the corresponding 2D MoS2/WSe2 hetero-interface. (d) STEM-EDS elemental maps to show the spatial distribution of constituent elements in the hetero vertical-stack. The scale bar is 10 nm. (e,f) EDS profiles obtained from each stack of (e) 2D MoS2 and (f) 2D WSe2.

Device applications of water-assisted 2D layer transfer and integration

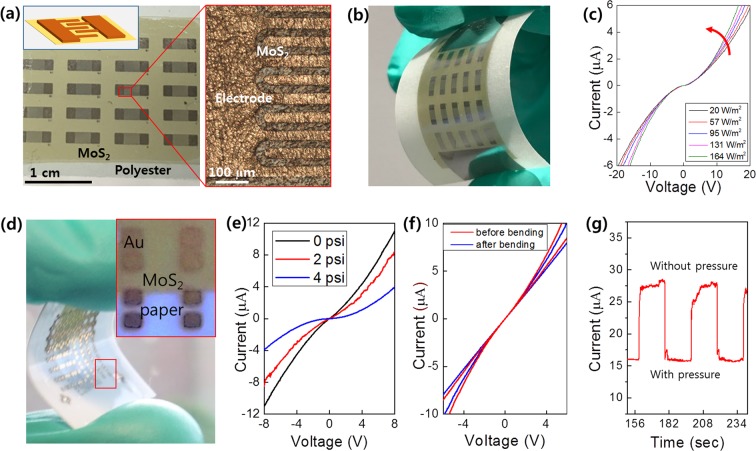

We demonstrate the versatility of this water-assisted layer integration method for realizing a variety of large-area 2D MoS2 layer devices assembled on unconventional substrates. Specifically, we showcase two examples of 2D MoS2-based photodetectors integrated on plastic substrates (Fig. 5(a–c)) and pressure sensors integrated on paper substrates (Fig. 5(d–g)). The photodetectors were fabricated by integrating 2D MoS2 layers on polyester substrates followed by depositing an array of interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) on the surface using a shadow mask. Figure 5(a) presents an image of a fabricated 2D MoS2 layers/polyester device showing multi-fingered IDEs (zoomed-in image) containing 20 individual device units. Figure 5(b) shows a camera image of the same device under bending, demonstrating its mechanical flexibility. We tested the photo-responsiveness of the device by characterizing its two-terminal current-voltage (I–V) transfer characteristics under an optical microscopy illumination of varying intensity. Figure 5(c) shows that the device exhibits systematically increasing current values with increasing illumination intensity, revealing its excellent photo-sensitivity. The pressure sensor devices were fabricated by integrating large-area 2D MoS2 layers on PMMA-coated paper substrates followed by depositing an array of metal electrodes. Figure 5(d) shows an image of a completed device confirming its excellent flexibility under mechanical bending. Figure 5(e) exhibits I–V characteristics with varying pressure levels exerted by the blow of argon (Ar) gas onto the surface of 2D MoS2 layers, revealing decreasing current with increasing pressure. Figure 5(f) presents the well-retained pressure sensitivity of a device, which was obtained before and after its slight mechanical bending. Figure 5(g) shows time-current characteristics from a device under the periodic application of Ar pressure, confirming its highly reversible sensitivity.

Figure 5.

(a–c) Large-area 2D MoS2 layers-based photodetectors integrated on polyester substrates. (a) Image of 2D MoS2 layers integrated on a flexible polyester substrate with IDEs (schematic in the inset) fabricated on the surface. The zoom-in optical microscopy image (right) shows the array of IDEs (50 μm spacing) on 2D MoS2 layers. (b) The same device under mechanical bending. (c) I–V characteristics obtained at various illumination intensities. (d–g) Large-area 2D MoS2 layers-based pressure sensors integrated on paper substrates. (d) Image of a device with metal (gold, Au) contacts under mechanical bending. (e) I–V characteristics obtained with varying pressure levels. (f) I–V characteristics for a pressure sensing of 3 psi with a device before/after slight mechanical bending. This device is different from the one used for (e). (g) Time-current characteristics from a pristine unbent device under a periodic pressure application of 5 psi.

Discussion

Principle for water-assisted spontaneous 2D layer separation

Lastly, we discuss about the fundamental principle behind the facile delamination of 2D layers inside water. We identify followings as two major factors; i.e., crystallographic layer orientation and surface wetting property of 2D MoS2 layers.

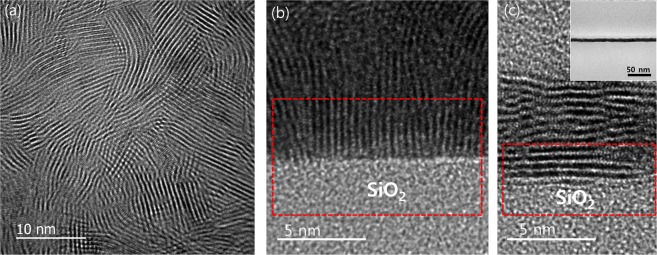

Influence of 2D layer orientation: We have observed that the spontaneous delamination of 2D layers inside water happens with 2D TMDs obtained from the sulfurization of thin metal seeds (typically <3 nm). 2D TMDs obtained in this manner exhibit horizontally-aligned basal planes of well-resolved layers; for example, horizontally-aligned 2D MoS2 layers of ~7–8 nm thickness obtained from the sulfurization of ~2.5 nm thick Mo have been confirmed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and cross-sectional TEM characterization (Supplementary Information, S4). Maintaining the small thickness of metal seeds is critically important to ensure that 2D TMD layers grow in horizontal orientation as identified in our previous studies32,34. In this case, weak molecular vdW attraction will be responsible for holding the 2D basal planes of diminished defect density to the SiO2 substrate surface, enabling facile water penetration in between them. Meanwhile, we have identified that the CVD sulfurization of thick (typically ~6–7 nm) metal seeds tends to grow 2D TMD layers in vertical alignment. Figure 6(a,b) presents the plane-view and cross-sectional HRTEM images of vertically-aligned 2D MoS2 layers prepared with the CVD sulfurization of ~7 nm thick Mo. It is noted that their 2D edge sites are predominantly exposed on the top surface (Fig. 6(a)) while 2D layers are vertically “rooted” in the SiO2 growth substrate (Fig. 6(b). This morphology is in sharp contrast to that of horizontally-aligned layers (Fig. 6(c)) and is believed to result from the actual chemical bonding of 2D MoS2 edges and SiO2 instead of weak vdW attraction. Accordingly, it has been identified that the water-assisted spontaneous separation of vertically-aligned 2D layers is much more difficult in terms of retaining their original shape and dimension on a large area. We have previously identified that 2D TMDs tend to rearrange their layer orientation with increasing physical confinement (increasing metal thickness) in a way to release the accumulating in-plane strain exerted by interconnecting 2D layers32. Moreover, we considered the theoretical condition to satisfy the water-assisted spontaneous separation of 2D layers by considering its associated surface energy contributions. The work of adhesion, W, required for the spontaneous 2D layer separation is expressed as , where γSW, γWL, and γSL are interfacial tension between substrate and water, water and 2D layer, substrate and 2D layer, respectively. In comparing the 2D MoS2 layers of horizontal vs. vertical orientation, we note that vertically-aligned 2D MoS2 layers exhibit significantly higher adhesion energy with respect to the SiO2 surface owing to the exposure of energetically reactive 2D edge sites; i.e., order-of-magnitude higher binding energy of 2D edges with dangling bonds over 2D basal panes with saturated bonds55,56. Accordingly, the value of γSL for vertically-aligned 2D MoS2 layers should be much smaller than that for horizontally-aligned ones, which further justifies the observed difficulty with their spontaneous separation inside water. Meanwhile, water can easily penetrate into the vdW gaps exposed in between horizontally-aligned 2D MoS2 layers assisted by their large γSL values. Specific values for these interfacial energy terms are currently unavailable in literature, which makes more precise quantification and elucidation difficult at present.

Figure 6.

(a) Plane-view and (b) cross-sectional HRTEM images of vertically-aligned 2D MoS2 layers grown on SiO2. 2D MoS2 layers are rooted in the SiO2 surface (red highlight in (b)). (c) Cross-sectional HRTEM image of horizontally-aligned 2D MoS2 layers grown on SiO2. 2D basal planes are in contact with the SiO2 surface. The inset shows a low magnification TEM image of the corresponding sample.

Influence of surface wetting property: As above mentioned, we have observed that 2D MoS2 layers aged for a few days after their growth typically exhibit better performance in terms of spontaneous layer separation inside water. In fact, it has been known that the water-wettability of 2D MoS2 layers increases with elongated air exposure owing to the lowered surface energy43,45, similar to the observation with graphene57,58. Accordingly, the surface of 2D MoS2 layers becomes more hydrophobic reflected by increasing water contact angle values, which becomes another determining factor for the water-assisted 2D layer separation. The separation efficacy of hydrophobic thin layers inside water has been recently studied59, which confirms a presence of strong capillary-induced “peeling” force exerted at their edges interfaced with water. A smaller amount of the capillary force is required to separate the thin layers of higher hydrophobicity while hydrophilic layers tend to get submerged inside water rather than being peeled off59. We believe that the identical principle should apply to the water-assisted spontaneous separation of 2D layers presented in this study. Indeed, we have observed that our as-grown 2D MoS2 layers of diminished hydrophobicity immersed into water immediately following their growth tend to get submerged without yielding the desired layer separation. This behavior is in sharp contrast to the facile and spontaneous layer separation typically observed with slightly-aged 2D MoS2 layers (Supplementary Information, S5).

In summary, we report a novel approach to reliably transfer a variety of 2D TMD layers and heterogeneously integrate them onto virtually arbitrary yet unconventional substrates. The presented method benefits from the water-assisted spontaneous separation of 2D layers, exhibiting distinguishable advantages over conventional approaches in terms of property preservation and size scalability. The intrinsic generality and versatility of this integration method has been verified with 2D TMDs of various kinds as well as their multi-component heterostructures. Moreover, its potential for device applications has been confirmed by demonstrating centimeter-scale 2D MoS2-based flexible photodetectors and pressure sensors integrated on exotic substrates, which are difficult to fabricate with any other conventional approaches.

Methods

Synthesis of 2D TMDs films

Various 2D TMD layers were grown via the sulfurization or seleneziation of transition metals deposited on SiO2/Si substrates using a home-built CVD chamber (Lindberg/Blue M Mini-Mite). High-quality transition metals (e.g., Mo, W, Pt) were deposited on cleaned SiO2/Si wafers (typical dimension: ~1 × 3 cm2) using an e-beam evaporation system (Thermionics VE-100). The metal-deposited SiO2/Si substrates were placed at the center zone of the CVD furnace while alumina boats containing S or Se powders were located at the upstream side. After the furnace was evacuated to the base pressure of ~1 mTorr, high purity Ar gas was flushed for ~10 min to remove any residuals in the chamber. The CVD furnace was gradually ramped up to reach the targeted growth temperatures, i.e., 800 °C for MoS2 and WSe2, and 400 °C for PtSe2, while the S and Se powders were vaporized at ~200 °C. The reaction was maintained for ~45 min under a constant supply of Ar gas at a flow rate of 100 sccm (standard cubic centimeter per minute) followed by natural cooling.

Structural characterization

TEM characterization was performed using a JEOL ARM200F Cs-corrected TEM at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. TEM samples were prepared by transferring 2D TMD films from SiO2/Si substrates to TEM grids by using water without compromising their intrinsic material quality of as-grown states. Cross-sectional TEM samples (2D MoS2 in Fig. 2 and 2D MoS2/WSe2 vertical-stack in Fig. 4) were prepared by focused ion beam (FIB)-based milling and lift-out techniques. Raman characterization was performed using a Renishaw system with a solid-state laser (spot size: 1 µm) at the excitation wavelength of 532 nm. Optical microscopy images were recorded in an Olympus BX60M optical microscope.

Device fabrication and characterization

Flexible photodetector devices were fabricating by depositing contact metals through an IDE shadow mask (Ossila) on the pre-integrated 2D MoS2 layers on polyester substrates. Photocurrent measurements were performed using a white LED light illumination of controlled intensity and I–V transfer characteristics were recorded by a semiconductor parameter analyzer (HP 4156 A) connected with a home-built probe station. Flexible pressure sensor devices were fabricated by integrating 2D MoS2 layers onto PMMA-coated cellulose papers followed by the deposition of top contact metals. Pressure sensing measurements were performed by introducing Ar gas of controlled pressure levels through a quarter-inch vacuum tubing using a flow controller.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CMMI-1728390) (M.S.S. and Y.J.). H.-S.C. was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Government (MSIP) (No. 2015R1C1A1A01052727). The work was supported in part by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20173010013340) (Y.J.).

Author Contributions

Y.J. conceived the idea and led the project. J.H.K., T.-J.K. and E.O. developed the water-assisted layer transfer method and prepared for the 2D layers-integrated samples under the guidance of Y.J. J.H.K. fabricated the flexible photo-responsive devices and performed the electrical, Raman, and water contact angle measurements under the guidance of Y.J. T.-J.K. investigated the mechanism for the water-assisted 2D layer separation under the guidance of Y.J. S.S.H. participated in the 2D materials growth and integration as well as the TEM characterization under the guidance of Y.J. K.H.O. and H.-S.C. M.S.S. participated in the materials growth and transfer under the guidance of Y.J. M.G.K. fabricated the pressure sensing devices and carried out their measurements under the guidance of Y.J. H.-S.C. performed the TEM characterization and analyzed the data. All authors participated in writing the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jung Han Kim and Tae-Jun Ko contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-37219-w.

References

- 1.Mak KF, Lee C, Hone J, Shan J, Heinz TF. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:136805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhimanapati GR, et al. Recent Advances in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano. 2015;9:11509–11539. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, et al. Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nature Reviews Materials. 2016;1:16042. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak KF, Shan J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics. 2016;10:216. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2015.282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhowalla M, et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nature Chem. 2013;5:263. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu Y, et al. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanomaterials for biosensing applications. Materials Chemistry Frontiers. 2017;1:24–36. doi: 10.1039/C6QM00195E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Yuan H, Sae Hong S, Li Y, Cui Y. Physical and chemical tuning of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:2664–2680. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00287C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan C, Zhang H. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheet-based composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:2713–2731. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00182F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan X, Wang C, Pan A, Yu R, Duan X. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides as atomically thin semiconductors: opportunities and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:8859–8876. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00507H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choudhary N, et al. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide hybrid materials for energy applications. Nano Today. 2018;19:16–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2018.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akinwande D, Petrone N, Hone J. Two-dimensional flexible nanoelectronics. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5678. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao L. Flexible device applications of 2D semiconductors. Small. 2017;13:1603994–n/a. doi: 10.1002/smll.201603994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novoselov KS, Mishchenko A, Carvalho A, Castro Neto AH. 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science. 2016;353:461. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Z, et al. 2D materials advances: from large scale synthesis and controlled heterostructures to improved characterization techniques, defects and applications. 2D Mater. 2016;3:042001. doi: 10.1088/2053-1583/3/4/042001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang K, et al. Layer-by-layer assembly of two-dimensional materials into wafer-scale heterostructures. Nature. 2017;550:229. doi: 10.1038/nature23905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhary N, et al. Two-dimensional lateral heterojunction through bandgap engineering of MoS2 via oxygen plasma. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2016;28:364002. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/28/36/364002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazyev OV, Kis A. MoS2 and semiconductors in the flatland. Mater. Today. 2015;18:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2014.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ling X, et al. Parallel Stitching of 2D Materials. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:2322–2329. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu M-H, et al. Determination of band alignment in the single-layer MoS2/WSe2 heterojunction. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7666. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu M-H, et al. Band alignment of 2D transition metal dichalcogenide heterojunctions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27:1603756. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201603756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duesberg GS. A perfect match. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:1075. doi: 10.1038/nmat4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pant A, et al. Fundamentals of lateral and vertical heterojunctions of atomically thin materials. Nanoscale. 2016;8:3870. doi: 10.1039/C5NR08982D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li M-Y, Chen C-H, Shi Y, Li L-J. Heterostructures based on two-dimensional layered materials and their potential applications. Mater. Today. 2016;19:322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das S, Robinson JA, Dubey M, Terrones H, Terrones M. Beyond graphene: progress in novel two-dimensional materials and van der Waals solids. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2015;45:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-matsci-070214-021034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geim AK, Grigorieva IV. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature. 2013;499:419. doi: 10.1038/nature12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang J, Tongay S, Zhou J, Li J, Wu J. Band offsets and heterostructures of two-dimensional semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;102:012111. doi: 10.1063/1.4774090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurarslan A, et al. Surface energy-assisted perfect transfer of centimeter-scale monolayer and few-layer MoS2 films onto arbitrary substrates. ACS Nano. 2014;8:11522–11528. doi: 10.1021/nn5057673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin Y-C, et al. Wafer-scale MoS2 thin layers prepared by MoO3 sulfurization. Nanoscale. 2012;4:6637–6641. doi: 10.1039/c2nr31833d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu K-K, et al. Growth of large-area and highly crystalline MoS2 thin layers on insulating substrates. Nano Lett. 2012;12:1538–1544. doi: 10.1021/nl2043612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung Y, et al. Metal seed layer thickness-induced transition from vertical to horizontal growth of MoS2 and WS2. Nano Lett. 2014;14:6842–6849. doi: 10.1021/nl502570f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong D, et al. Synthesis of MoS2 and MoSe2 films with vertically aligned layers. Nano Lett. 2013;13:1341–1347. doi: 10.1021/nl400258t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choudhary N, et al. Strain-driven and layer number-dependent crossover of growth mode in van der Waals heterostructures: 2D/2D layer-by-layer horizontal epitaxy to 2D/3D vertical reorientation. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;5:1800382. doi: 10.1002/admi.201800382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choudhary N, et al. Centimeter scale patterned growth of vertically stacked few layer only 2D MoS2/WS2 van der Waals heterostructure. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25456. doi: 10.1038/srep25456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam MA, et al. Noble metal-coated MoS2 nanofilms with vertically-aligned 2D layers for visible light-driven photocatalytic degradation of emerging water contaminants. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14944. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14816-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung Y, Shen J, Sun Y, Cha JJ. Chemically synthesized heterostructures of two-dimensional molybdenum/tungsten-based dichalcogenides with vertically aligned layers. ACS Nano. 2014;8:9550–9557. doi: 10.1021/nn503853a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, et al. From bulk to monolayer MoS2: evolution of Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22:1385–1390. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201102111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verble JL, Wietling TJ, Reed PR. Rigid-layer lattice vibrations and van der waals bonding in hexagonal MoS2. Solid State Commun. 1972;11:941–944. doi: 10.1016/0038-1098(72)90294-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaur APS, et al. Surface energy engineering for tunable wettability through controlled synthesis of MoS2. Nano Lett. 2014;14:4314–4321. doi: 10.1021/nl501106v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi J, et al. Hierarchical, dual-scale structures of atomically thin MoS2 for tunable wetting. Nano Lett. 2017;17:1756–1761. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b05066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow PK, et al. Wetting of mono and few-Layered WS2 and MoS2 films supported on Si/SiO2 substrates. ACS Nano. 2015;9:3023–3031. doi: 10.1021/nn5072073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai S, Jeon J, Song Y-J, Lee S. Water-penetration-assisted mechanical transfer of large-scale molybdenum disulfide onto arbitrary substrates. RSC Adv. 2016;6:57497–57501. doi: 10.1039/C6RA09681F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Islam MA, et al. Centimeter-scale 2D van der Waals vertical heterostructures integrated on deformable substrates enabled by gold sacrificial layer-assisted growth. Nano Lett. 2017;17:6157–6165. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozbial A, Gong X, Liu H, Li L. Understanding the intrinsic water wettability of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) Langmuir. 2015;31:8429–8435. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Annamalai M, et al. Surface energy and wettability of van der Waals structures. Nanoscale. 2016;8:5764–5770. doi: 10.1039/C5NR06705G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao, et al. Aging of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2628–2635. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tongay S, et al. Tuning interlayer coupling in large-area heterostructures with CVD-grown MoS2 and WS2 monolayers. Nano Lett. 2014;14:3185–3190. doi: 10.1021/nl500515q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu C-R, Chang X-R, Wu C-H, Lin S-Y. The growth mechanism of transition metal dichalcogenides by using sulfurization of pre-deposited transition metals and the 2D crystal hetero-structure establishment. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42146. doi: 10.1038/srep42146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong Y, et al. Vertical and in-plane heterostructures from WS2/MoS2 monolayers. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:1135. doi: 10.1038/nmat4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue Y, et al. Scalable production of a few-layer MoS2/WS2 vertical heterojunction array and its application for photodetectors. ACS Nano. 2016;10:573–580. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong Y, et al. Two-step growth of two-dimensional WSe2/MoSe2 heterostructures. Nano Lett. 2015;15:6135–6141. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu H, et al. A vertical WSe2–MoSe2 p–n heterostructure with tunable gate rectification. RSC Adv. 2018;8:25514. doi: 10.1039/C8RA03398F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin Y-C, et al. Atomically thin resonant tunnel diodes built from synthetic van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7311. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahjouri-Samani M, et al. Patterned arrays of lateral heterojunctions within monolayer two-dimensional semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7749. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghosh R, et al. Large area chemical vapor deposition growth of monolayer MoSe2 and its controlled sulfurization to MoS2. J. Mater. Res. 2016;31:917–922. doi: 10.1557/jmr.2016.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho S-Y, et al. Highly Enhanced Gas Adsorption Properties in Vertically Aligned MoS2Layers. ACS Nano, 2015. 2015;9:9314–9321. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Islam MA, et al. Three dimensionally-ordered 2D MoS2 vertical layers integrated on flexible substrates with stretch-tunable functionality and improved sensing capability. Nanoscale. 2018;10:17525–17533. doi: 10.1039/C8NR05362F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kozbial A, et al. Study on the Surface Energy of Graphene by Contact Angle Measurements. Langmuir. 2014;30:8598–8606. doi: 10.1021/la5018328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, et al. Effect of airborne contaminants on the wettability of supported graphene and graphite. Nature Materials. 2013;12:925–931. doi: 10.1038/nmat3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khodaparast S, Boulogne F, Poulard C, Stone HA. Water-Based Peeling of Thin Hydrophobic Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:154502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.154502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.