Abstract

The Krüppel-like transcription factor 14 (KLF14) is a critical regulator of a wide array of biological processes. However, the role of KLF14 in colorectal cancer (CRC) isn't fully investigated. This study aimed to explore the clinicopathological significance and potential role of KLF14 in the carcinogenesis and progression of CRC. A tissue microarray consisting of 185 samples from stage I-III CRC patients was adopted to analyze the correlation between KLF14 expression and clinicopathological parameters, as well as overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). The underlying mechanisms of altered KLF14 expression on glycolysis were studied using in vitro and patients' samples. The results showed that KLF14 expression was downregulated in CRC than their normal controls. Low KLF14 expression correlated with advanced T stage (P< 0.001) and N stage (P= 0.040), and larger tumor size (P= 0.008). Lost KLF14 expression implied shorter OS and DFS after colectomy in both univariate and multivariate survival analysis (P<0.05). Experimentally, restore KLF14 expression significantly decreased the rate of glycolysis both in vitro and in patients' sample. Mechanically, KLF14 regulated glycolysis by downregulating glycolytic enzyme LDHB. Collectively, KLF14 is a novel prognostic biomarker for survival in CRC, and downregulation of KLF14 in CRC prompts glycolysis by target LDHB. Hence, KLF14 could constitute potential prognostic predictors and therapeutic targets for CRC.

Keywords: Colorectal Cancer, Glycolysis, KLF14, LDHB

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, accounting for approximately 9.7% of total cancer cases and approximately 8.5% of cancer related deaths1, and its incidence is also increasing steadily these years in China2. Despite significant advances in multidisciplinary treatment approaches, such as surgery, chemotherapy, bio-target therapy, and radiotherapy, the improvement in overall survival (OS) in patients with CRC is limited. Consequently, there is an urgent need to explore novel prognostic markers and therapeutic targets, both of which may be realized through a more sophisticated understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in CRC carcinogenesis and metastases.

Krüppel-like transcription factor (KLF) family of transcription factors regulate a wide array of biological processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and invasion 3-6. In mammals, 17 KLF genes families (KLF1-KLF17) have been identified, and both tumor suppressive and oncogenic functions have been defined for different KLFs 3, 7-10. In recent years, KLF14 (also called BTEB5) has got significant attention. Genetic studies have revealed that KLF14 may serve as a master regulator of gene expression in adipose tissue 11, and there appears to be a relationship between KLF14 and hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes 12. Recently, de Assuncao et al. reported that KLF14 functioned as an activator for the generation of lipid signaling molecules13. Importantly, KLF14 transcription is found to be significantly downregulated in multiple types of cancers, and its depletion promotes AOM/DSS-induced colon tumorigenesis10. However, its prognostic value and underline mechanism in CRC is not fully investigated.

In the present study, we first investigated the prognostic value of KLF14 in tissue microarray (TMA) consisting of 185 CRC , and then explored the in vitro effects and underline mechanism of KLF14 expression on the glycolysis of human colon cell lines and CRC tissues.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

A total of 185 primary CRC specimens and their normal control from adjacent colonic tissues were collected from patients who underwent radical surgery from January 2000 to December 2006. These patients included 24 at stage I, 81 at stage II, and 80 at stage III. None of the patients received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and all the patients were treated with routine chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy after surgery according to NCCN guideline for colon or rectal cancer. The mean follow-up period was 62 months. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Use of Human Subjects at Taizhou Municipal Hospital. The clinicopathological findings were determined according to the 8th edition classification of CRC by the World Health Organization and International Union against Cancer Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging system [14]. All tumor tissues were diagnosed histopathologically by at least two trained pathologists.

TMA and Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Construction of the TMA and IHC staining was performed as described previously14. Briefly, sections were incubated with 1:100 dilution of anti-KLF14 (21234-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), or 1:150 dilution of anti-LDHB (19987-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) overnight at 4C, and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit Envision System Plus-HRP (Dako Cytomation) for 30 min at room temperature. After rinsing three times in PBS for 10 min each, the sections were incubated with DAB for 1 min, counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Phosphate-buffered saline was used as a negative control.

Data were assessed by two independent single-blinded pathologists. A semiquantitative scoring system 14 was used to evaluate both staining intensity (0, no staining; 1+, weak staining; 2+, moderate staining; 3+, strong staining) and the percentage of stained cells (0, <5%; 1, 5%-25%; 2, 26%-50%; 3, 51%-75%; and 4, >75%). The scores for staining intensity and percentage of positive cells were then multiplied to generate the immunoreactivity score for each case15, 16. All cases were sorted into two groups according to the immunoreactivity score. High expression of KLF14 or LDHB was defined as detectable immunoreactions in the nucleus or in cytoplasm with an immunoreactivity score of ≥4.

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from colon cancer cells using the TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcription was performed using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time) kit (RR036A, Takara). The cDNA was subjected to quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using the SYBR Green PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and the assay was performed on an ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detector. β-actin was used as an internal control. The relative levels of target genes were quantified and analyzed using SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by normalizing to the β-actin and related to the amount of target gene in control sample. Three independent experiments were performed to analyze the relative gene expression and each sample was tested in triplicate.

Cell culture and transient transfection

The human colon cancer cell lines RKO and HCT116 were used for functional and mechanism study. Colon cancer cell lines were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a humidified 37°C incubator supplemented with 5% CO2. pcDNA3.1-KLF14 or control vector pcDNA3.1 plasmids was transfected into RKO or HCT116 with lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen), respectively.

Western blot assay

Standard Western blotting was carried out using whole-cell protein lysates of colon cancer cells and primary antibodies anti-KLF14 (21234-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), or anti-LDHB (19987-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were used. Equal-amount protein sample loading was monitored using an anti-β-actin antibody.

Glycolysis analysis

Glucose Uptake Colorimetric Assay Kit (Biovision, Milpitas, CA, USA) and Lactate Colorimetric Assay Kit (Biovision, Milpitas, CA, USA) were purchased to examine the glycolysis process in colon cancer cells according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCR was performed to test expression of glycolytic enzymes. All reactions were run in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was conducted with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism v.6 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Chi-square test was used to analyze the relationship between clinicopathological parameters and KLF14 expressions. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression model. The in vitro study results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance or independent sample t test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All confidence intervals (CIs) were stated at the 95% confidence level.

Results

Relationship between KLF14 Expression and clinicopathological characteristics

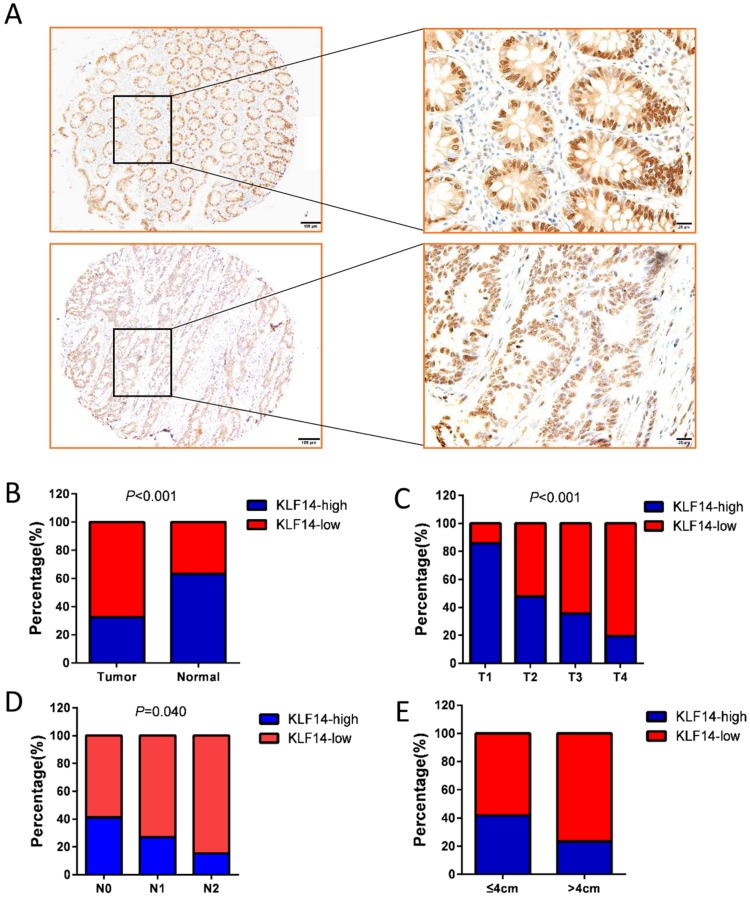

KLF14 protein was found to be mainly nucleus staining. Examples of KLF14 staining are shown in Fig. 1A. High KLF14 expression was detected in 60 (32.42%) cases, which was significantly lower than their normal control (63.25%) (P<0.001) (Fig. 1B). KLF14 expression and the clinicopathological characteristics were shown in Table 1. KLF14 expression was found to be inversely correlated with T stage (P< 0.001), N stage (P= 0.040), and tumor size (P= 0.008) (Fig. 1C-E).

Figure 1.

KLF14 expression in colorectal cancer. (A) Examples of immunohistochemical staining of the expression of KLF14 expression in normal colon tissues (up panel) and colorectal cancer (down panel). As visualized in a 100× (left panels) and 400×magnifications (right panels). (B)KLF14 expression was significantly decreased in cancer tissues than their normal control (32.42% vs 63.25%, P<0.001) KLF14 expression was inversely correlated with T stage (P< 0.001) (C), N stage (P= 0.040) (D), and tumor size (P= 0.008) (E).

Table 1.

Association between KLF14 expression and clinicpathological factors in colorectal cancers (n = 185)

| Variable | n | KLF14 Expression | χ2 Value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Gender | 3.129 | 0.077 | |||

| Male | 82 | 61 | 21 | ||

| Female | 103 | 64 | 39 | ||

| Age | 0.165 | 0.685 | |||

| ≤60 | 61 | 40 | 21 | ||

| >60 | 124 | 85 | 39 | ||

| T category | 19.743 | <0.001a | |||

| T1 | 7 | 1 | 6 | ||

| T2 | 23 | 11 | 12 | ||

| T3 | 73 | 47 | 26 | ||

| T4 | 82 | 66 | 16 | ||

| N stage | 6.439 | 0.040 | |||

| N0 | 107 | 65 | 42 | ||

| N1 | 52 | 38 | 14 | ||

| N2 | 26 | 22 | 4 | ||

| Tumor size | 7.108 | 0.008 | |||

| ≤4cm | 91 | 53 | 38 | ||

| >4cm | 94 | 72 | 22 | ||

| Pathological grading | 1.251 | 0.263 | |||

| High/ Moderate | 166 | 110 | 56 | ||

| Poor/ undifferentiation | 19 | 15 | 4 | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | 2.908 | 0.088a | |||

| Negative | 174 | 115 | 59 | ||

| Positive | 11 | 10 | 1 | ||

| Ki67 | 3.219 | 0.073 | |||

| Negative | 52 | 30 | 22 | ||

| Positive | 133 | 95 | 38 | ||

a Fisher's exact test

Prognostic value of KLF14 in CRC

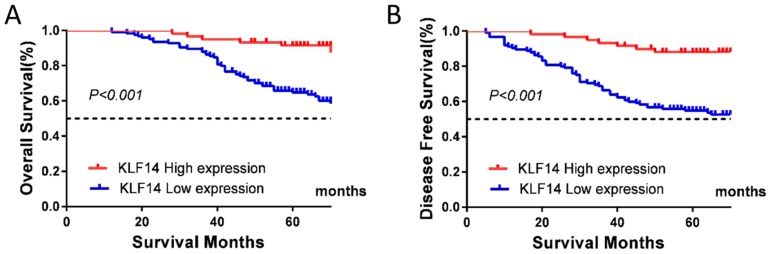

At the end of follow-up, tumor relapse was observed in 65 (35.1 %) of 185 samples, and 57 patients (30.8%) died of the disease. Low KLF14 expression was significantly associated with worse OS (P< 0.001; Fig. 2A) and disease-free survival (DFS) (P< 0.001; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Low KLF14 expression predicts poor prognosis for CRC. KLF14 expression levels was investigated in TMA consisting of 185 CRC patients. (A, B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the correlation of KLF14 expression with OS (A) and DFS (B) in the cohort. Log-rank tests were used to determine statistical significance (P < 0.001).

The univariate Cox regression model demonstrated that T stage (P =0.029), N stage (P < 0.001), tumor grade (P < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion(P < 0.001), Ki67 index (P =0.011), and KLF14 expression (P < 0.001) were correlated with OS (Table 2), whereas T stage (P =0.014), N stage (P < 0.001), tumor grade (P < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion(P < 0.001), Ki67 index (P =0.004), and KLF14 expression (P < 0.001) were correlated with DFS (Table 2). Multivariate analysis after adjustment revealed that N stage (P< 0.001) and KLF14 expression (P= 0.006) were independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 2), while N stage (P<0.001), Ki67 index (P= 0.047), and KLF14 expression (P= 0.001) were independent prognostic factor for DFS for CRC patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of survival in CRC

| Overall Survival | Disease Free Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Univariate analysis | ||||

| Gender | 1.039(0.613-1.761) | 0.887 | 1.100(0.671-1.802) | 0.705 |

| Age | 1.024(0.585-1.792) | 0.934 | 1.007(0.599-1.694) | 0.978 |

| T category | 3.104(1.122-8.589) | 0.029 | 3.537(1.285-9.732) | 0.014 |

| N stage | 5.352(2.974-9.633) | <0.001 | 4.102(2.430-6.920) | <0.001 |

| Pathological grading | 3.604(1.936-6.712) | <0.001 | 3.014(1.636-5.551) | <0.001 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 5.821(2.910-11.644) | <0.001 | 5.152(2.604-10.194) | <0.001 |

| Ki67 | 2.543(1.244-5.199) | 0.011 | 2.836(1.402-5.736) | 0.004 |

| KLF14 | 0.205(0.088-0.477) | <0.001 | 0.200(0.091-0.437) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| T category | 1.339(0.830-2.159) | 0.232 | 1.299(0.843-2.002) | 0.235 |

| N stage | 3.150(2.146-4.625) | <0.001 | 2.770(1.939-3.956) | <0.001 |

| Pathological grading | 1.289(0.901-1.843) | 0.165 | 1.198(0.842-1.705) | 0.316 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 1.340(0.599-2.997) | 0.476 | 1.258(0.570-2.774) | 0.569 |

| Ki67 | 1.940(0.900-4.182) | 0.091 | 2.108 (1.009-4.401) | 0.047 |

| KLF14 | 0.297(0.125-0.708) | 0.006 | 0.265(0.119-0.590) | 0.001 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

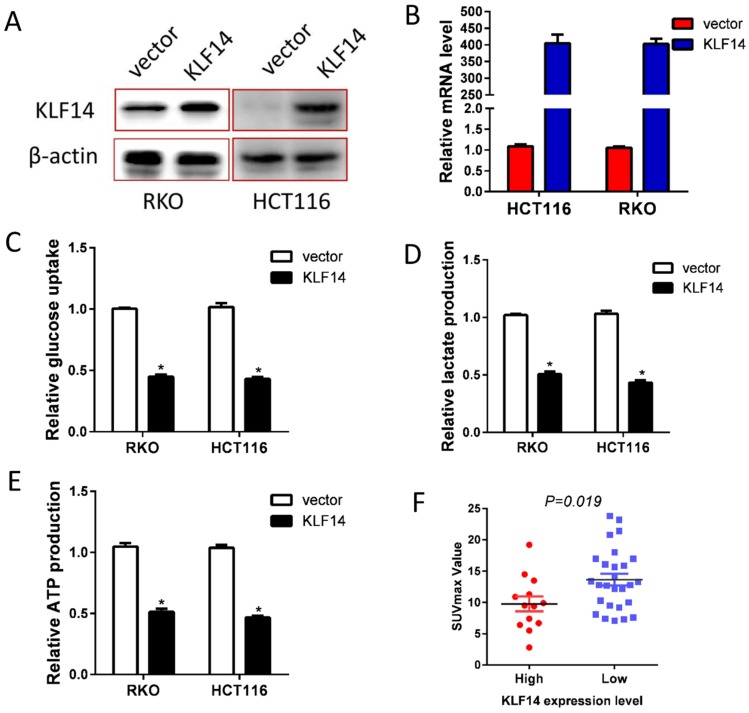

Restore KLF14 expression impaired glycolysis

Glucose metabolism reprogram is one of the fundamental for tumor growth and metastases. Hence, we explored the impact of KLF14 expression on CRC glycolysis. KLF14 expression was restored in RKO and HCT116 cells by transient transfected pcDNA3.1-KLF14 or control vector, and overexpression efficiency were determined by RT-PCR and western blotting (Fig. 3A, 3B). As anticipated, restore KLF14 expression significantly decreased the glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP production in RKO and HCT116 cells (Fig. 3C-3E). SUVmax in PET/CT scan is a reflection of the glycolysis rate in vivo. In a series of 40 patients with CRC who received PET/CT scan before surgery, we found significantly lower SUVmax value in patients with high KLF14 expression than those with low expression (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Restore KLF14 expression impaired glycolysis. KLF14 expression was restored in RKO and HCT116 cells by transient transfected pcDNA3.1-KLF14 or control vector, and overexpression efficiency were determined by Western blotting (A) and RT-PCR (B). Overexpression of KLF14 significantly decreased the glucose uptake(C), lactate production (D), and ATP production (E) in RKO and HCT116 cells. SUVmax in PET/CT scan is a reflection of the glycolysis rate in vivo. There was significantly lower SUVmax value in patients with high KLF14 expression than those with low expression in a series of 40 patients with CRC who received PET/CT scan before surgery (F). All in vitro experiments were carried out in triplicate.

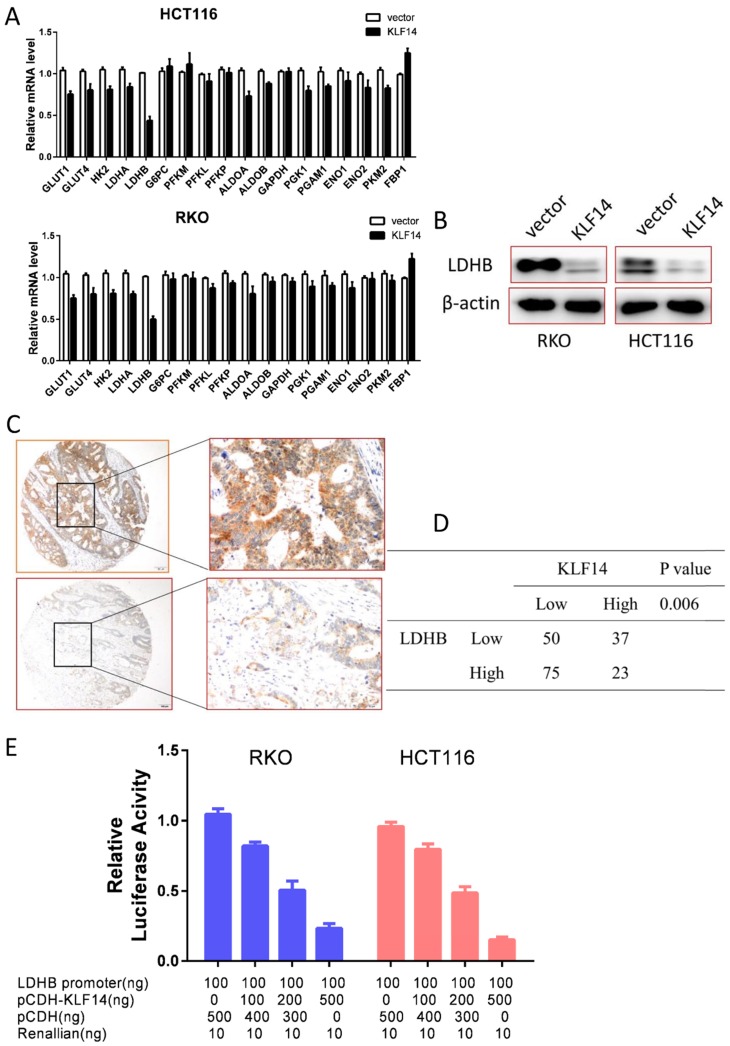

KLF14 regulates glycolysis by target LDHB

Glycolysis is a multi-step enzymatic reaction involved with a series of glycolytic enzymes. To explore the underline mechanism of KLF14 on glycolysis in CRC, we performed RT-PCR to determine the transcriptional levels of these enzymes in RKO and HCT116 cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, overexpression KLF14 upregulated or downregulated several glycolytic enzymes in glycolysis process, with the most significantly decreased was LDHB in both RKO and HCT116 cells. Western blot analysis further confirmed that overexpression KLF14 expression could also decrease LDHB expression at protein level in these two cells (Fig. 4B). Importantly, there was a negative relationship between KLF14 and LDHB expression in TMA (P<0.001) (Fig. 4C and 4D). As KLF14 belongs to classic KLF transcriptional factor family, we then obtained a luciferase reporter construct (pGL3-LDHB-Luc) containing a segment of the human LDHB promoter and examined the effect of KLF14 on the promoter activity. Dual luciferase assay demonstrated that KLF14 decreased the LDHB promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

KLF14 regulates glycolysis by target LDHB. (A) Overexpression KLF14 upregulated or downregulated several glycolytic enzymes in glycolysis process, with the most significantly decreased was LDHB in both RKO and HCT116 cells. (B)Western blot analysis further confirmed that overexpression KLF14 expression could also decrease LDHB expression at protein level in these two cells. (C) Examples of immunohistochemical staining of high (up panel) and low (down panel) LDHB expression in colorectal cancer. As visualized in a 100× (left panels) and 400×magnifications (right panels). (D) There was a negative relationship between KLF14 and LDHB expression in TMA (P<0.001) (E) Dual luciferase assay demonstrated that KLF14 decreased the LDHB promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner. All in vitro experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Discussion

The development and progress of CRC is a multistep process involving the accumulation of multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations that lead to the activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor. In present study, we explored the character of KLF14 in the pathogenesis and progression of CRC. KLF14 is downregulated in CRC, and it could only be detected in 32.42% tumor tissues, while it is highly expressed in 63.25% of their normal control. Decreased KLF14 expression is correlated with T stage, N stage, and tumor size. More importantly, KLF14 expression is validated as an independent prognostic factor in CRC after radical resection. Taken together, these data strongly suggested that KLF14 as a tumor suppressor that played an important role in CRC progression.

Tumor cells growth with unrestricted division and proliferation. Relentless biosynthesis of macromolecules that are needed for the growth of newly divided cells requires the uptake of glucose and other carbon sources in excess of energetic needs17-19. The tumor cell has to modify their metabolism to adapt the circumstance20. Aerobic glycolysis, also named as the Warburg effect, is a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, a feature of which is increased lactate production even at normal oxygen concentrations, and is considered to be one of the hallmarks of cancer development and progression19, 21, 22. Our functional studies indicated that KLF14 had strong tumor suppressor characters, with overexpression of KLF14 significantly decreased glycolysis rate in vitro. The role of KLF14 in glycolysis was further supported by the in vivo study that KLF14 expression was negatively associated with SUVmax, which is an indication of glycolysis rate in vivo. Because glycolysis is a process involved a series of glycolytic enzymes and KLF14 is a classic transcriptional factor, we tested whether the effect of KLF14 on glycolysis was by regulating target glycolytic enzyme. As expected, KLF14 expression led to the decreased or overexpressed RNA levels of some glycolytic enzymes. In additional, the expression level of LDHB, which catalyzes the interconversion of pyruvate and lactate with concomitant interconversion of NADH and NAD+ in a post-glycolysis process, was dramatically modulated by KLF14 expression. Further study found that KLF14 was able to inactivate KLF14 promoter activities at dose dependent. It has been reported that KLF14 is associated with type 2 diabetes12, forced expression of KLF14 in the livers of normal mice impaired glucose tolerance23. Thus, it is not surprise that KLF14 regulate glycolysis process in CRC.

There are some limitations in our study. First, no in vivo experiments using animals were performed to observe the effects of KLF14 on progression and metastases from mouse models. Thus, further in vivo animal studies are warranted to confirm our findings. Second, some glycolytic enzymes may be regulated by post-translational modification, we did not explore such mechanism in present study.

Collectively, our findings identify KLF14 as a tumor suppressor that plays an important role in the development and progression of CRC by regulating glycolysis process. Further characterization of KLF14 may lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets for better clinical management of CRC.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Medical and Health Program of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant No. 2018KY905) and National Science Foundation of China (No. 81802374). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66:115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu G, Wu F, Wang E. KLF8 Promotes Temozolomide Resistance in Glioma Cells via beta-Catenin Activation. Cellular physiology and biochemistry: international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2016;38:1596–604. doi: 10.1159/000443100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun H, Peng Z, Tang H, Xie D, Jia Z, Zhong L, Loss of KLF4 and consequential downregulation of Smad7 exacerbate oncogenic TGF-beta signaling in and promote progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue Y, Gao S, Liu F. Genome-wide analysis of the zebrafish Klf family identifies two genes important for erythroid maturation. Developmental biology. 2015;403:115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nuez B, Michalovich D, Bygrave A, Ploemacher R, Grosveld F. Defective haematopoiesis in fetal liver resulting from inactivation of the EKLF gene. Nature. 1995;375:316–8. doi: 10.1038/375316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiwari N, Meyer-Schaller N, Arnold P, Antoniadis H, Pachkov M, van Nimwegen E. et al. Klf4 is a transcriptional regulator of genes critical for EMT, including Jnk1 (Mapk8) PloS one. 2013;8:e57329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan Y, Li Z, Kong X, Jia Z, Zuo X, Gagea M, KLF4-mediated Suppression of CD44 Signaling Negatively Impacts Pancreatic Cancer Stemness and Metastasis. Cancer research; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li D, Peng Z, Tang H, Wei P, Kong X, Yan D. et al. KLF4-mediated negative regulation of IFITM3 expression plays a critical role in colon cancer pathogenesis. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:3558–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan G, Sun L, Shan P, Zhang X, Huan J, Zhang X. et al. Loss of KLF14 triggers centrosome amplification and tumorigenesis. Nature communications. 2015;6:8450. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Small KS, Hedman AK, Grundberg E, Nica AC, Thorleifsson G, Kong A. et al. Identification of an imprinted master trans regulator at the KLF14 locus related to multiple metabolic phenotypes. Nature genetics. 2011;43:561–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Dina C, Welch RP. et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nature genetics. 2010;42:579–89. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Assuncao TM, Lomberk G, Cao S, Yaqoob U, Mathison A, Simonetto DA. et al. New role for Kruppel-like factor 14 as a transcriptional activator involved in the generation of signaling lipids. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:15798–809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.544346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Q, Wu J, Wei P, Xu Y, Zhuo C, Wang Y. et al. Overexpression of forkhead Box C2 promotes tumor metastasis and indicates poor prognosis in colon cancer via regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. American journal of cancer research. 2015;5:2022–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Jiang Z, Zhang Y, Wang X, Liu L, Fan Z. RNA sequencing analysis reveals protective role of kruppel-like factor 3 in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:21984–93. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu S, Ma C, Shan S, Zhou L, Li W. High expression of matrix metalloproteinases 16 is associated with the aggressive malignant behavior and poor survival outcome in colorectal carcinoma. Scientific reports. 2017;7:46531. doi: 10.1038/srep46531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer DE, Harris MH, Plas DR, Lum JJ, Hammerman PS, Rathmell JC. et al. Cytokine stimulation of aerobic glycolysis in hematopoietic cells exceeds proliferative demand. FASEB J. 2004;18:1303–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1001fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell metabolism. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Li Y, Xu J, Wang S, Xu Y, Li X. et al. Aldolase B Overexpression is Associated with Poor Prognosis and Promotes Tumor Progression by Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Cellular physiology and biochemistry: international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2017;42:397–406. doi: 10.1159/000477484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno-Sanchez R, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Marin-Hernandez A, Saavedra E. Energy metabolism in tumor cells. The FEBS journal. 2007;274:1393–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garber K. Energy deregulation: licensing tumors to grow. Science. 2006;312:1158–9. doi: 10.1126/science.312.5777.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Tong X, Gu F, Zhang L, Chen W, Cheng X. et al. The KLF14 transcription factor regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2017;292:21631–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]