Abstract.

Greece experienced the largest European West Nile virus (WNV) outbreak in 2010 since the 1996 Romania epidemic. West Nile virus reemerged in southern Greece during 2017, after a 2-year hiatus of recorded human cases, and herein laboratory findings, clinical features, and geographic distribution of WNV cases are presented. Clinical specimens from patients with clinically suspected WNV infection were sent from local hospitals to the Microbiology Department of Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and were tested for the presence of specific anti-WNV antibodies and WNV RNA. From July to September 2017, 45 confirmed or probable WNV infection cases were identified; 43 of them with an acute/recent infection, of which 24 (55.8%) experienced WNV neuroinvasive disease (WNND). Risk factors for developing WNND included advanced age, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. A total of four deaths (16.7%) occurred, all in elderly patients aged > 70 years. Thirty-nine cases were identified in regional units that had not been affected before (36 in Argolis and two in Corinth, northeastern Peloponnese, and one in Rethymno, Crete). The remaining four cases were reported from previously affected regional units of northwestern Peloponnese. The reemergence of WNV after a 2-year hiatus of recorded human cases and the spread of the virus in newly affected regions of the country suggests that WNV has been established in Greece and disease transmission will continue in the future. Epidemiological surveillance, intensive mosquito management programs, and public awareness campaigns about personal protective measures are crucial to the prevention of WNV transmission.

INTRODUCTION

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne arbovirus of the Flaviviridae family.1 In nature, WNV is maintained in an enzootic cycle that involves wild and domestic avian species acting as amplifying hosts and ornithophilic mosquitoes, notably of Culex species.2,3 Transmission to humans considered to be incidental or dead-end hosts occurs following a bite from an infected female mosquito.4

Most human WNV infections remain asymptomatic, whereas West Nile fever (WNF), a mild and self-limited febrile illness, develops in about 20% of the infected individuals. Less than 1% of WNV infections present with central nervous system (CNS) inflammation manifested by a wide variety of neurologic symptoms and ending up to severe, sometimes fatal, illnesses (e.g., aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, and acute flaccid paralysis).5,6

Following its first isolation in 1937, from an adult female with febrile illness in the West Nile district of Uganda, WNV expanded geographically and the frequency of recorded WNV outbreaks increased over the past two decades.7,8 In Europe, WNV emerged in the Camargue area of southern France in the 1960s. In 1996, an urban epidemic of West Nile encephalitis/meningitis occurred in Bucharest, Romania, with at least 393 hospitalized cases and 17 deaths.9 Three years later, an outbreak of WNV was recorded in the Volgograd region of Russia with 84 cases of acute meningoencephalitis and 40 fatalities.10 At the same time, WNV moved from the Eastern to the Western Hemisphere and was first identified in the New York City area.11 Within the following decade, WNV became endemic in the United States of America, whereas both sporadic cases and major outbreaks have been reported in the European continent and the Mediterranean basin.12

In the summer of 2010, a WNV infection outbreak in humans was documented for the first time in Greece, particularly in Central Macedonia, near the city of Thessaloniki.13 Among 262 probable and confirmed cases of WNV infection, 197 were neuroinvasive cases and 35 had a fatal outcome.14 Southern Greece also experienced outbreaks of WNV infections for four consecutive years (2011–2014), with 99 WNND cases and 15 deaths (M. Mavrouli, unpublished data). After a 2-year hiatus of reported WNV cases, the virus reemerged in southern Greece and a WNV outbreak among humans occurred not only in regions that had already been affected in previous years but also in new ones that had never reported human cases before. The aim of the present study was to determine the laboratory, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics of WNV infection cases diagnosed during the 2017 outbreak caused by the WNV reemergence in southern Greece.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

Serum and/or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens were collected from individuals originating from southern Greece and considered suspected for WNV infection, especially from late June through September, when other causes of fever are least common. Patients presented with febrile illness with or without rash, and/or neurological manifestations ranging from headache to aseptic meningitis and/or encephalitis. Serum and CSF specimens were sent from local hospitals to the Microbiology Department of Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and were tested for the presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against WNV, whereas CSF samples were also used for the detection of WNV RNA. Of all WNV cases diagnosed in 2017, information regarding clinical manifestations, underlying medical conditions, and demographic characteristics were collected through a national dedicated form provided from the Hellenic Center for Disease Control and Prevention (HCDCP) that accompanied the specimens sent to the diagnosing laboratory. More detailed information was acquired from the treating physician if the patient originated from a region where WNV cases were not previously reported.

Case definition.

Confirmed and probable WNV cases were characterized based on a slightly modified 2008 European Union case definition that had also been used in previous WNV infection outbreaks in Greece.13,15 In detail, a confirmed case was defined as a patient meeting any of the clinical criteria (e.g., meningitis, encephalitis, and/or fever ≥ 38.5°C without specific diagnosis) and at least one of the following laboratory criteria: 1) detection of WNV RNA in whole blood and/or CSF, 2) presence of WNV IgM antibodies in CSF with or without WNV IgG antibodies, and 3) detection of increasing levels of IgM and IgG antibodies against WNV in consecutive serum specimens. A case was considered probable if the patient met the previously described clinical criteria and WNV IgM antibodies, with or without IgG antibodies, were detected in the patient’s serum specimen. The HCDCP was immediately informed for both confirmed and probable WNV cases and performed case investigation within 24 hours after diagnosis, including detailed travel history during the maximum incubation period to confirm the probable place of infection.

Laboratory methods.

West Nile virus IgG and IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA).

West Nile virus IgG DxSelect and IgM capture DxSelect ELISA kits (Focus Diagnostics Inc., Cypress, CA) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and are commercially available for the detection of specific anti-WNV IgG and IgM antibodies.16 Patient sera and CSF samples were diluted in the ratio of 1:101 and 1:2, respectively, in sample diluent.17 Both ELISAs were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) and dengue virus (DENV) antibodies detection.

Specimens found positive for WNV antibodies during the first month (July) of the 2017 WNV outbreak were also tested for specific antibodies against TBEV (TBE/FSME IgM and TBE/FSME IgG ELISA kits; IBL International GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) and DENV (DENV IgM Capture DxSelect and DENV IgG DxSelect ELISA kits; Focus Diagnostics Inc.) to exclude possible cross-reactivity of these viruses with the WNV serologic assays.

Reverse transcriptase real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for WNV RNA detection.

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcription into single-stranded complementary DNA as well as amplification, and detection of WNV genome were performed as described elsewhere.15

Geographic information systems (GIS).

The GIS played an important role as regards the analysis and visualization of the data. The available epidemiological data comprising the age, gender, location of patients’ probable place of infection, underlying medical conditions, the severity of WNV infection were stored and processed in specially designed databases in GIS environment (ArcMap 10.3.1; ESRI, Redlands, CA). Among other results presented herein, the geographical distributions of diagnosed WNV cases (WNND and WNF) during the 2017 WNV outbreak in southern Greece are presented.

RESULTS

From July to September of 2017, 45 confirmed or probable cases of WNV infection were identified and reported to the HCDCP from 180 (25%) patients who presented with signs and symptoms compatible to WNV infection. Forty-three individuals were diagnosed with acute/recent WNV infection, of whom 24 (55.8%) developed severe disease with neurological manifestations and were classified as WNV neuroinvasive disease (WNND) cases, whereas the remaining 19 (44.2%) were characterized as WNF cases.

WNND cases: clinical and laboratory characteristics.

All patients with neurological clinical picture manifested with acute onset of fever associated with neck stiffness, altered level of consciousness (confusion, disorientation, and lethargy), limb weakness, and/or abnormal neuroimaging findings. WNND cases were hospitalized for general supportive care, lumbar puncture, ruling out other possible etiologies, and/or observation of neurological deficits.

According to the WNV case definition, nine of the 24 WNND cases (37.5%) were characterized as confirmed, whereas the remaining 15 (62.5%) as probable. All WNND cases met the aforementioned clinical criteria characteristic of WNV neurological syndrome. In detail, two WNND cases (C1 and C2) were confirmed because only anti-WNV IgM antibodies were detected in the only available CSF specimens. In cases C3–C9, anti-WNV IgM with or without IgG antibodies were detected in both serum and CSF. Cases C10–C18 provided only serum samples with WNV IgM and IgG antibodies and were first defined as probable. However, taking into account that high titers of both WNV IgM and IgG antibodies were detected and patients originated from regions that had never reported WNV cases before, groups C10–C18 could be considered confirmed. Regarding the probable WNND cases (C19–C23), only WNV IgM antibodies were detected in serum samples. Ten WNND cases (41.7%) presented with encephalitis, eight (33.3%) with meningoencephalitis, and six (25%) with meningitis. Of the seven CSF specimen tested, two were found positive for the presence of the WNV genome.

WNND cases: demographic data and underlying diseases.

The median age of WNND cases was 64.5 years, ranging from 15 to 91 years, whereas that of WNF cases was 53 years (range: 20–83 years). The distribution of WNND and WNF cases according to the patient’s age is shown (Figure 1). Individuals older than 60 years had almost five times higher risk for developing WNND than younger individuals (relative risk [RR] = 4.9, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.16–11.26). Four patients (16.7%) aged more than 70 years with neurological manifestations had a fatal outcome. The incidence of WNND was higher among males (more than 2.5-fold of the WNND incidence among females) and the male-to-female ratio was 2.4:1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the 43 West Nile virus infection cases (WNND and WNF) diagnosed in Southern Greece, 2017, by age group. WNF = West Nile fever.

Fifteen of the 24 WNND cases (62.5%) had at least one underlying medical condition that usually renders patients vulnerable to the development of severe neuroinvasive disease. The most common underlying disorders were hypertension (N = 13) and diabetes mellitus (N = 9), followed by dyslipidemia (N = 3), cancer (N = 1), stroke (N = 1), rheumatoid arthritis (N = 1), and chronic depressive syndrome (N = 1). In addition, two patients were immunosuppressed.

West Nile fever cases: clinical and laboratory characteristics.

West Nile fever was most commonly characterized by an abrupt onset of moderate to high fever, followed by headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and intense fatigue. A centrally and peripherally distributed maculopapular rash (chest, bilateral upper extremities, and/or back) occurred in approximately 21.1% of WNF cases. In addition, 12 patients (63.2%) presented gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. All the non-neuroinvasive cases of WNV infection were considered probable because patients C25–C43 provided only serum samples with WNV IgM antibodies with or without WNV IgG antibodies. The presence of anti-WNV IgG antibodies but not IgM in serum samples from two clinically compatible cases was the only evidence of previous infection. Although these patients originated from Argolis regional unit, the time course of WNV infection could not be accurately estimated and were not further included in the study.

The review of the patients’ reporting forms concerning the exposure to other flaviviruses through vaccination or natural contact revealed that none of the patients had been vaccinated against yellow fever virus (YFV), TBEV, and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) or had recently traveled to other flaviviruses endemic areas. All WNV-positive specimens were found negative for TBEV IgG and IgM and DENV IgM antibodies. IgG cross-reactivity was seen with DENV in a small percentage (8.9%) of the aforementioned samples; however, the DENV IgG titers were always lower than those against WNV.

Geographic distribution of WNV infection cases.

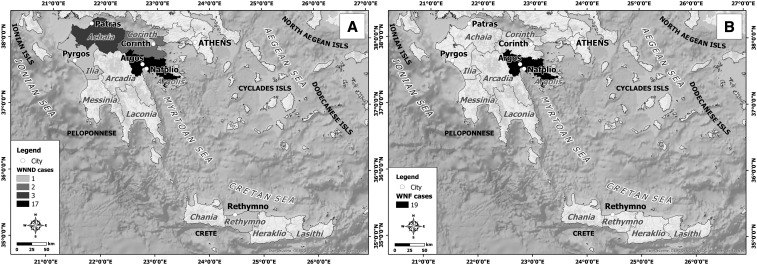

Patients’ demographic data and a detailed travel history during the incubation period (2–14 days before symptoms onset) led to the identification of the suspected place of exposure. Forty-two WNV cases originated from Peloponnese peninsula and one from Crete, the largest Greek island (Figure 2). Thirty-nine cases were detected in new affected areas. In detail, most of them (36 cases, 85.7%) were identified in Argos–Mycenae (N = 24; 13 WNND and 11 WNF), Nafplio (N = 11; four WNND and seven WNF), and Epidavros (N = 1; one WNF) municipalities of eastern Peloponnese (Figure 3), which are located almost 95 km from the metropolitan area of Athens, where WNV outbreaks in humans were recorded for four consecutive years, 2011–2014. A 6-km waterfront zone connects Nea Kios and Nafplio cities and is used as a corridor on the migratory voyage of some avifauna species (Figure 4A). In addition, two WNND cases were detected in Corinth regional unit of northeastern Peloponnese, located about 78 km west of Athens. One WNND case originated from Rethymno regional unit, Crete, within a distance of 185 miles from the capital of Greece (Figure 3). The remaining four WNND cases were reported from Achaia (N = 3) and Ilia (N = 1) regional units of northwestern Peloponnese (Figure 3A). The western part of these areas presents wetlands and marches that serve as stopping areas of water birds during their migration from breeding sites in Northern Europe to overwintering areas in Africa and vice versa.18 In particular, Kotychi Lagoon is located in the forest of Strofilia, northern to the Achaia prefecture, and along with Prokopos Lagoon and Marsh Lamia are protected by the Ramsar Convention (Legislative Decree 191/1974) because they have been designated as wetlands of international significance (https://www.ramsar.org/) (Figure 4B).

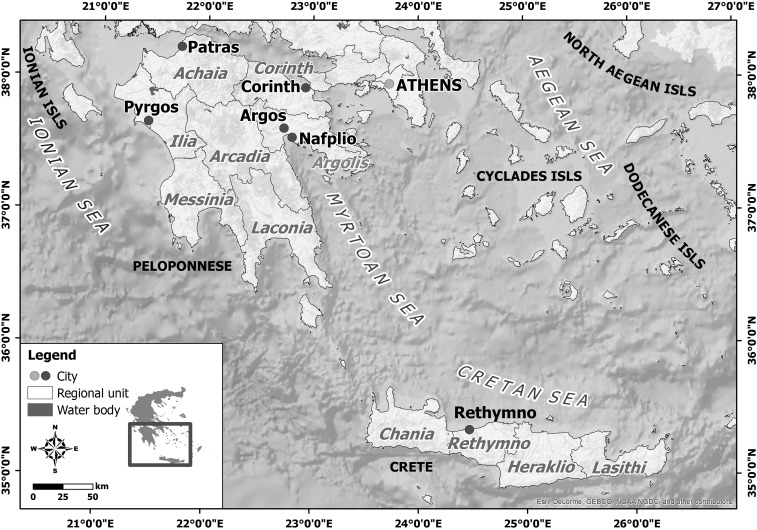

Figure 2.

Regional units of Southern Greece with diagnosed West Nile virus (WNV) infections during the 2017 WNV outbreak.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of diagnosed (A) WNND cases and (B) West Nile fever cases during the 2017 West Nile virus outbreak in southern Greece.

Figure 4.

(A) Detailed geographic distribution of diagnosed West Nile virus (WNND and WNF) cases in Argolis regional unit. The wetland of Nafplio–Nea Kios in Argolis regional unit is also depicted. (B) Wetlands in Achaia and Ilia regional units: Araxos Lagoon is situated at the northwestern edge of Peloponnese. It is separated from the Gulf of Patras by an elongated sandy islet and extensive sand dune formations from the Ionian Sea. Kotychi Lagoon, the largest lagoon in the Peloponnese, is situated to the north of the Lehaina region, Ilia regional unit, and is separated from the Ionian Sea on the west side by a narrow 5-km length sand strip. Kotychi Lagoon, Prokopos Lagoon, and Marsh Lamia form a wetland network protected by the Ramsar Convention (Legislative Decree 191/1974). WNF = West Nile fever.

DISCUSSION

West Nile virus is a reemerging zoonotic pathogen posing a significant threat to humans because of its rapid geographical expansion and ability to cause severe neuroinvasive disease with various presentations, including meningitis and/or encephalitis. It is endemic in Africa, Eurasia, America, Australia, and the Middle East. Outbreaks in humans and equines have been reported in the following European and neighboring countries: Romania (1996–1997; 2003–2009), the Czech Republic (1997), Russia (1999), France (2000, 2003, 2004, 2006), Italy (1998, 2008, 2009), Hungary (2000–2009), Spain (2004), and Portugal (2004).19 During 2010, an outbreak of WNV infection in humans occurred for the first time in Central Macedonia, northern Greece and was considered the second largest WNV epidemic in Europe since the 1996 Romania outbreak.14 In the same year, large outbreaks occurred in other countries of southeastern Europe (e.g., Romania, Hungary, Italy, and Spain) as well as in Russia, Turkey, and Israel.19 Most outbreaks in Western Europe have been caused by WNV lineage 1.20 In Eastern Europe, however, lineage 2, which emerged in Hungary in 2004, has been responsible for human mortality, particularly in Greece.21,22 Both in 2011 and 2012, Greece reported the highest number of cases in comparison to other European countries. West Nile virus transmission was no longer limited to northern Greece but dispersed southward to newly affected areas of Attica that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece.15,23 The number of Greek WNV cases declined gradually in 2013 and 2014 until no human cases were identified in 2015. However, the virus continued to circulate in Greek territories as it was demonstrated by serological testing of birds in 2015,24 whereas WNV infections were recorded in a number of European cities (e.g., Milan, Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, and Sofia).25 The dramatic reduction of WNV cases may have resulted from the mosquito management strategy, that is, the timely and proper use of larvicides directly to mosquito-breeding sites in late spring and early summer that reduced the number of emerging mosquitoes, and the preventive measures taken by the community to limit their exposure to WNV-infected mosquitoes. In addition, the development of immune response against WNV may have reduced human WNV cases by depleting the susceptible human population. Nur et al.26 analyzed the characteristics of an outbreak of WNF among migrants in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo, and demonstrated that human WNV outbreaks could result from the introduction of the virus into immunologically naive populations with insufficient levels of immunity against the virus. It is also possible that WNV caused infections that were asymptomatic, as occurs in approximately 80% of cases or remained undetected even including neuroinvasive cases.

In July 2017, after a 2-year period without reported cases, WNV reemerged in southern Greece, particularly in the Peloponnese peninsula. A new geographical pattern of virus circulation was observed with a more dispersed distribution of cases mainly in new previously unaffected regions in southern Greece. The reoccurrence of WNV infection cases may be explained by not only the WNV reintroduction by migratory birds but also overwintering cycles supported by indigenous avian species and infected mosquitoes surviving the winter. The 2017 WNV outbreak peaked in the second half of July and most of WNV cases were recorded in Argos–Mycenae and Nafplio municipalities of Argolis regional unit. WNND cases were also reported in Achaia and Ilia regional units of northwestern Peloponnesus that had been previously affected during the 2012–2013 WNV transmission periods (M. Mavrouli, unpublished data). One WNND case originated from Rethymno regional unit on the island of Crete and reflected not only the complex epidemiology of the virus but also the inability to predict the areas of WNV circulation.

The analysis of environmental data related to the affected areas in GIS environment revealed that landscape features, such as natural and constructed wetlands, seem to influence WNV transmission and disease incidence. Most WNV outbreaks in Europe have occurred near river deltas such as the Rhone Delta in southern France, the Danube Delta in Romania, and the Volga Delta in southern Russia.19 The combination of specific ecologic environments and large numbers of migratory and indigenous bird species with high population densities of ornithophilic mosquitoes provides optimal conditions for mosquito-transmitted diseases. Except from rural areas, large human outbreaks were also reported in densely populated urban European countries (e.g., Bucharest in Romania, Volgograd in Russia, and Thessaloniki and Athens in Greece) and the United States, indicating that urbanization combined with vegetative landscaping and surface water bodies may evolve to a high risk factor for emergence of human WNV infection.19

From July to September 2017, clinical specimens were obtained from patients presenting with fever and/or meningoencephalitis during the WNV transmission season. Of the 43 detected acute/recent WNV cases, 24 experienced severe neurological manifestations, of whom four died. The number of 2017 WNND cases diagnosed in Argolis regional unit was slightly smaller than that in Attica regional unit during 2011 or 2013 WNV outbreak. However, the WNND cases detected in 2011 or 2013 were dispersed in larger and more densely populated urban areas. The increased awareness regarding the clinical presentation of human WNV disease due to previous years’ WNV epidemics led to rapid recognition of patients with mild or severe clinical picture compatible with WNV infection. Apart from WNND cases, 19 WNF cases were also detected during the 2017 WNV transmission period. The true incidence of WNV fever was probably underestimated because most cases are asymptomatic and self-limited. In addition, clinicians were mainly interested in collecting samples from individuals experiencing neuroinvasive disease and being in greater need of supportive care. During 2017, in the European Union, 156 human WNV cases were reported in Romania (66 cases), Italy (57), Hungary (21), Austria (5), Croatia (5), France (1), and Bulgaria (1). In the neighboring countries, 84 cases were reported: Serbia (49), Israel (28), and Turkey (7). In addition, 21 deaths were recorded in Romania (14 deaths), Hungary (2), Serbia (2), Italy (1), Croatia (1), and Turkey (1).27

Given that many patients presented to the clinician a few days after onset of illness, WNV isolation from the blood of WNND patients was not fruitful because of low-level viremia, and serological diagnosis was the only option available. An IgM antibody capture ELISA, detecting anti-WNV IgM antibodies in the serum or CSF, provided a strong evidence of recent WNV infection. In this study, the TaqMan assay positive results were obtained from CSF specimens acquired too early after the onset of clinical illness. Because IgM antibodies do not cross the blood–brain barrier, their presence in CSF strongly indicated CNS infection.

The overall data of both the present study and previous seroprevalence surveys conducted in Greece or in other countries indicated that elderly people are more susceptible to be infected and develop WNND.14,15,18,28–30 The increased probability of WNND occurrence and high mortality rates observed in the elderly may result from the decreased capacity of these individuals to develop a protective immune response that contributes to infection control. For the aforementioned reason, increased risk in the development and severity of WNND is more often observed in immunosuppressed patients rather than in immunocompetent individuals.15 Apart from advanced age, hypertension followed by diabetes mellitus were identified as possible risk factors for increased susceptibility to WNND occurrence. Hypertension may increase the permeability of the blood–brain barrier facilitating WNV entry into the CNS, whereas diabetes may raise the level and duration of WNV viremia.31,32 The higher incidence of WNND cases among male patients probably reflected behavioral factors associated with outdoor activities leading to increased exposure to mosquitoes, especially in rural areas and near surface water bodies.33

West Nile virus exhibits close antigenic relationships with members of the JEV serocomplex as well as with YFV, DENV, and TBEV that belong to the Flaviviridae family.34 Vaccination against YFV or previous infection with another flavivirus must be considered when interpreting the laboratory findings because cross-reactive antibodies against WNV may be detected in individuals recently vaccinated against or infected with another flavivirus.31 One limitation of the present study was that WNV-positive specimens were not confirmed by serologic assays to rule out possible cross-reactions with Usutu virus (USUV). Up to now, few sporadic human USUV infections have been reported in Italy (2009–2011), Croatia (2013), and Germany (2016).35 On the contrary, USUV infection cases have not been detected in Greece, except for one serum sample of a domestic pigeon found positive for USUV neutralizing antibodies in northern Greece, 2010.36

The risk of WNV transmission is complex and multifactorial; it concerns the virus, the vectors, the animal reservoirs, the environmental conditions, and human behavior. Prevention or reduction of WNV transmission depends on successful control of vector abundance or interruption of human–vector contact. Targeted WNV surveillance within mosquito populations may contribute to the well-timed detection of the virus before its emergence in equine species or human populations and thus to proper adjustment of integrated vector management approaches and enhancement of disease awareness.

In conclusion, the reoccurrence of human WNV infection cases after 2 years of apparent silence and the subsequent geographic expansion of the virus in newly affected areas demonstrate that Greece provides the appropriate ecological and climatic conditions for WNV circulation. Laboratory test results should be interpreted accurately based on clinical manifestations, recent travel history, flaviviral vaccine administration, and evidence of WNV activity in the area of interest. Taking into account the limited treatment and prevention options against WNV and the unpredictable mode of virus emergence, vigilant epidemiological surveillance, intensive mosquito management programs, and public awareness campaigns about personal protective measures are crucial to the prevention of WNV transmission, especially among susceptible population groups, during the period of mosquitoes’ maximum annual activity.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank all physicians and health professionals from the local hospitals who sent samples for testing WNV-suspected cases and contributed to the diagnosis of the cases, and especially Maria Pavlaki from the General Hospital of Argos.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mavrouli M, Vrioni G, Vlahakis A, Kapsimali V, Mavroulis S, Antypas A, Tsakris A, 2015. West Nile virus: biology, transmission, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, therapeutic approaches, climatic correlates and prevention. Acta Microbiol Hellenica 60: 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komar N, Langevin S, Hinten S, Nemeth N, Edwards E, Hettler D, Davis B, Bowen R, Bunning M, 2003. Experimental infection of North American birds with the New York 1999 strain of West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis 9: 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molaei G, Andreadis TG, Armstrong PM, Anderson JF, Vossbrinck CR, 2006. Host feeding patterns of Culex mosquitoes and West Nile virus transmission, northeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 468–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marka A, et al. 2013. West Nile virus state of the art report of MALWEST project. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10: 6534–6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colpitts TM, Conway MJ, Montgomery RR, Fikrig E, 2012. West Nile virus: biology, transmission, and human infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 25: 635–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen LR, Marfin AA, 2002. West Nile virus: a primer for the clinician. Ann Intern Med 137: 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smithburn KC, Hughes TP, Burke AW, Paul JH, 1940. A neurotropic virus isolated from the blood of a native of Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 20: 471–473. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubler DJ, 2007. The continuing spread of West Nile virus in the western hemisphere. Clin Infect Dis 45: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai TF, Popovici F, Cernescu C, Campbell GL, Nedelcu NI, 1998. West Nile encephalitis epidemic in southeastern Romania. Lancet 352: 767–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platonov AE, et al. 2001. Outbreak of West Nile virus infection, Volgograd region, Russia, 1999. Emerg Infect Dis 7: 128–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nash D, et al. 2001. The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med 344: 1807–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calistri P, Giovannini A, Hubalek Z, Ionescu A, Monaco F, Savini G, Lelli R, 2010. Epidemiology of West Nile in Europe and in the Mediterranean basin. Open Virol J 4: 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papa A, et al. 2010. Ongoing outbreak of West Nile virus infections in humans in Greece, July–August 2010. Euro Surveill 15: 1–5, pii: 19644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danis K, et al. 2011. Outbreak of West Nile virus infection in Greece, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis 17: 1868–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vrioni G, Mavrouli M, Kapsimali V, Stavropoulou A, Detsis M, Danis K, Tsakris A, 2014. Laboratory and clinical characteristics of human West Nile virus infections during 2011 outbreak in southern Greece. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 14: 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogrefe WR, Moore R, Lape-Nixon M, Wagner M, Prince HE, 2004. Performance of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using a West Nile virus recombinant antigen (preM/E) for detection of West Nile virus- and other flavivirus-specific antibodies. J Clin Microbiol 42: 4641–4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prince HE, Lape’-Nixon M, Moore RJ, Hogrefe WR, 2004. Utility of the focus technologies West Nile virus immunoglobulin M capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for testing cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol 42: 12–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadjichristodoulou C, et al. 2015. West Nile Virus seroprevalence in the Greek population in 2013: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 10: e0143803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paz S, Semenza JC, 2013. Environmental drivers of West Nile fever epidemiology in Europe and western Asia—a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10: 3543–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanciotti RS, et al. 1999. Origin of West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science 286: 2333–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papa A, Bakonyi T, Xanthopoulou K, Vazquez A, Tenorio A, Nowotny N, 2011. Genetic characterization of West Nile virus lineage 2, Greece 2010. Emerg Infect Dis 17: 920–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barzon L, et al. 2013. Genome sequencing of West Nile virus from human cases in Greece, 2012. Viruses 5: 2311–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danis K, et al. 2011. Ongoing outbreak of West Nile virus infection in humans, Greece, July to August 2011. Euro Surveill 16: 1–5, pii: 19951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaintoutis SC, Gewehr S, Mourelatos S, Dovas CI, 2016. Serological monitoring of backyard chickens in central Macedonia-Greece can detect low transmission of West Nile virus in the absence of human neuroinvasive disease cases. Acta Trop 163: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ECDC , 2017. West Nile Fever—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2015 Available at: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/AER_for_2015-West-Nile-fever.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 26.Nur YA, Groen J, Heuvelmans H, Tuynman W, Copra C, Osterhaus AD, 1999. An outbreak of West Nile fever among migrants in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg 61: 885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ECDC , 2018. Epidemiological Update: West Nile Virus Transmission Season in Europe, 2017 Available at: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2017. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 28.Anis E, Grotto I, Mendelson E, Bin H, Orshan L, Gandacu D, Warshavsky B, Shinar E, Slater PE, Lev B, 2014. West Nile fever in Israel: the reemergence of an endemic disease. J Infect 68: 170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernabeu-Wittel M, Ruiz-Perez M, del Toro MD, Aznar J, Muniain A, de Ory F, Domingo C, Pachon J, 2007. West Nile virus past infections in the general population of southern Spain. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 25: 561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pervanidou D, et al. 2014. West Nile virus outbreak in humans, Greece, 2012: third consecutive year of local transmission. Euro Surveill 19: 1–11, pii: 20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell GL, Marfin AA, Lanciotti RS, Gubler DJ, 2002. West Nile virus. Lancet Infect Dis 2: 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray K, et al. 2006. Risk factors for encephalitis and death from West Nile virus infection. Epidemiol Infect 134: 1325–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pezzotti P, et al. 2011. Prevalence of IgM and IgG antibodies to West Nile virus among blood donors in an affected area of north-eastern Italy, summer 2009. Euro Surveill 16: 1–5, pii: 19814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansfield KL, Horton DL, Johnson N, Li L, Barrett AD, Smith DJ, Galbraith SE, Solomon T, Fooks AR, 2011. Flavivirus-induced antibody cross-reactivity. J Gen Virol 92: 2821–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaibani P, Rossini G, 2017. An overview of Usutu virus. Microbes Infect 19: 382–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaintoutis SC, et al. 2014. Evaluation of a West Nile virus surveillance and early warning system in Greece, based on domestic pigeons. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 37: 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]