Abstract.

According to the World Health Organization, 98% of fatal dengue cases can be prevented; however, endemic countries such as Colombia have recorded higher case fatality rates during recent epidemics. We aimed to identify the predictors of mortality that allow risk stratification and timely intervention in patients with dengue. We conducted a hospital-based, case–control (1:2) study in two endemic areas of Colombia (2009–2015). Fatal cases were defined as having either 1) positive serological test (IgM or NS1), 2) positive virological test (RT-PCR or viral isolation), or 3) autopsy findings compatible with death from dengue. Controls (matched by state and year) were hospitalized nonfatal patients and had a positive serological or virological dengue test. Exposure data were extracted from medical records by trained staff. We used conditional logistic regression (adjusting for age, gender, disease’s duration, and health-care provider) in the context of multiple imputation to estimate exposure to case–control associations. We evaluated 110 cases and 217 controls (mean age: 35.0 versus 18.9; disease’s duration pre-admission: 4.9 versus 5.0 days). In multivariable analysis, retro-ocular pain (odds ratios [OR] = 0.23), nausea (OR = 0.29), and diarrhea (OR = 0.19) were less prevalent among fatal than nonfatal cases, whereas increased age (OR = 2.46 per 10 years), respiratory distress (OR = 16.3), impaired consciousness (OR = 15.9), jaundice (OR = 32.2), and increased heart rate (OR = 2.01 per 10 beats per minute) increased the likelihood of death (AUC: 0.97, 95% confidence interval: 0.96, 0.99). These results provide evidence that features of severe dengue are associated with higher mortality, which strengthens the recommendations related to triaging patients in dengue-endemic areas.

Introduction

Dengue is one of the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral diseases worldwide, with an incidence that has increased by 30-fold in the past 50 years and an estimated occurrence of 50–100 million symptomatic cases each year.1–3 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), early detection and access to timely and proper medical care would decrease dengue case fatality rates (CFR) below 1%.4 Unfortunately, during the last decade the reported number of deaths related to dengue increased and several countries recorded high CFR during recent epidemics.5–7 Moreover, although mortality rates from most infectious diseases have decreased, dengue mortality has increased by about 50% between 2005 and 2015 worldwide.8 This is also the case for Colombia where dengue imposes an enormous social and economic burden and constitutes an important public health problem, especially during the disease outbreaks.9,10

The incidence of dengue has risen during the last decade particularly among adults due to the demographic transitions experienced in regions such as Southeast Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean. These transmission settings set a more complex scenario for risk stratification and clinical decision-making due to a higher burden of chronic noncommunicable comorbidities among these patients.8,11 Studies conducted in populations from these regions have reported high prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and renal failure in severe and fatal dengue cases, and also have proposed that these chronic health conditions might increase the risk of adverse outcomes even in patients undergoing adequate clinical care.12,13 Thus, host-specific health status, secondary infections, and barriers to timely access to health care have been described as potential contributors to fatal outcomes in dengue.14

The WHO has formulated a comprehensive strategy to reduce the burden of dengue. Among the recommendations to lower dengue mortality are the study and implementation of risk assessment tools that prompt an early detection and appropriate management of cases.15 However, the available evidence on this matter has been mainly derived from observational studies focused on the determination of predictors of severe dengue (i.e., transfusion requirement, hypovolemic shock, etc.) but not mortality.13,16–18 Case–control studies, especially if the autopsy reports and tissue specimens are available, might not only complement our knowledge about prediction of mortality in dengue, but also our understanding of its physiopathology; however, such studies are uncommon in the literature and characteristically included small number of fatal cases.19 The aim of this study was to provide evidence that features of severe dengue, including clinical and laboratory parameters that can be easily assessed early during the course of the disease, are actually associated with higher mortality in dengue patients.

Methods

We conducted a hospital-based, matched, case–control study (1:2) in patients who attended any of the reference health-care centers in the two endemic states of Colombia (Santander and Valle del Cauca) between 2009 and 2015 (Table 1). In Colombia, the report of all suspected deaths attributable to dengue infection to the national surveillance system is mandatory. Further evaluation of each fatal case is conducted by a multidisciplinary committee (denominated “unit of analysis”) based on the assessment of epidemiological, clinical, histopathological findings, and laboratory diagnostic data, under the direction of the Instituto Nacional de Salud.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases and controls by year and state of enrollment

| Year | Santander | Valle del Cauca | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | Case | Control | |

| 2009 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 18 |

| 2010 | 14 | 28 | 12 | 24 | 26 | 52 |

| 2011 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 2012 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 14 |

| 2013 | 20 | 39 | 7 | 15 | 27 | 54 |

| 2014 | 23 | 47 | 3 | 6 | 26 | 53 |

| 2015 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| Total | 77 | 152 | 33 | 65 | 110 | 217 |

In this study, all patients had evidence of clinical manifestations of dengue infection documented on their clinical records. Attending physicians at each health-care center also registered patient’s severity using the most current WHO criteria.20,21 Dengue infection was defined if at least one the following criteria were met: 1) positive serological (IgM or NS1) testing for dengue virus (DENV) in a single specimen; 2) laboratory evidence of DENV nucleic acid in serum or DENV antigen in tissue (RT-PCR or viral isolation), and 3) for fatal cases for which autopsy reports were available, presence of macroscopic and microscopic findings compatible with death by dengue (Tables 2 and 3). Medical records from cases and controls as well as autopsy reports (if available) for cases were systematically reviewed and clinical data extracted by trained physicians and nurses using standardized forms. We collected information about potential predictors (exposures) as it was recorded by attending physicians at the time of hospital admission in the following domains: socio-demographics, medical history, symptoms and signs from physical examination, and laboratory data (hemogram) when available. In fatal cases, we additionally collected a subset of clinical findings recorded 48 hours before death (respiratory distress, consciousness impairment, seizures, edema, jaundice, cyanosis, hepatomegaly, and signs of shock).

Table 2.

Criteria to classify fatal cases according with diagnostic test and autopsy

| Case | Clinic | NS1 | IgM | PCR | Autopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (+) | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 2 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 3 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (−) |

| 4 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| 5 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 6 | (+) | NR | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| 7 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 8 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 9 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 10 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 11 | (+) | NR | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| 12 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 13 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 14 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 15 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (−) |

| 16 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (−) |

| 17 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 18 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 19 | (+) | NR | NR | NR | (+) |

| 20 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 21 | (+) | NR | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| 22 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 23 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 24 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (+) |

| 25 | (+) | NR | NR | NR | (+) |

| 26 | (+) | (+) | NR | NR | (+) |

| 27 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 28 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 29 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (+) |

| 30 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (−) |

| 31 | (+) | NR | NR | (−) | (+) |

| 32 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (−) |

| 33 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| 34 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 35 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| 36 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 37 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 38 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 39 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 40 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 41 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 42 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 43 | (+) | NR | NR | (−) | (+) |

| 44 | (+) | NR | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| 45 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 46 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (−) |

| 47 | (+) | NR | NR | (−) | (+) |

| 48 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (−) |

| 49 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 50 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 51 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | NR |

| 52 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| 53 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 54 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 55 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | NR |

| 56 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | NR |

| 57 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (+) |

| 58 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (−) |

| 59 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (−) |

| 60 | (+) | NR | (−) | NR | (+) |

| 61 | (+) | NR | NR | (−) | (+) |

| 62 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (+) |

| 63 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (−) |

| 64 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| 65 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| 66 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 67 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | (−) |

| 68 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| 69 | (+) | NR | NR | (−) | (+) |

| 70 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 71 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 72 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | NR |

| 73 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 74 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 75 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 76 | (+) | NR | NR | NR | (+) |

| 77 | (+) | NR | NR | NR | (+) |

| 78 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 79 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 80 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 81 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 82 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 83 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 84 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 85 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 86 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | NR |

| 87 | (+) | (+) | NR | NR | NR |

| 88 | (+) | (+) | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 89 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | (+) |

| 90 | (+) | NR | (+) | NR | NR |

| 91 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 92 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| 93 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 94 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 95 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | NR |

| 96 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 97 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 98 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 99 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | NR |

| 100 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 101 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 102 | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| 103 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 104 | (+) | (+) | NR | (+) | (+) |

| 105 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| 106 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | NR |

| 107 | (+) | NR | NR | (+) | NR |

| 108 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | NR |

| 109 | (+) | NR | (−) | (+) | NR |

| 110 | (+) | NR | (+) | (−) | (−) |

(+) = positive result; (−) = negative result; NR = no report (not done/not available).

Table 3.

Distribution of cases and controls according to dengue confirmation method

| Method | Fatal cases | Controls |

|---|---|---|

| NS1 positive | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| IgM positive | 26 (23.6) | 217 (100.0) |

| PCR positive | 20 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Autopsy findings | 14 (12.7) | – |

| Combination ≥ 2 criteria | 49 (44.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 110 (100.0) | 217 (100) |

Figures in each cell correspond to counts (percentage).

Cases were patients admitted to a hospital, who died as result of an acute dengue infection. Fatal cases were comprehensively identified according to the definition of case study mentioned before, from at least one of the following sources: the official registries from the surveillance system of Instituto Nacional de Salud or local health authorities from the states of Santander and Valle del Cauca. Serum samples obtained at hospital admission and tissues from autopsies were processed and analyzed by one of the following institutions: Arbovirus Laboratory of the Instituto Nacional de Salud or the Health Sciences Faculty Laboratories of the Universidad Industrial de Santander or the Universidad del Valle and Pathology Departments of Instituto Nacional de Salud, Universidad del Valle and Universidad Industrial de Santander.

Controls were hospitalized patients, who recovered from an acute dengue infection according to the criteria 1 and 2 (see previously mentioned), identified and selected from two different sources, independently of their medical history, clinical or laboratory information. For the years 2009, 2010, and 2011, controls were randomly selected from a dataset of a multicenter hospital-based cohort study conducted by our group during that period, aimed at identifying risk factors of progression to severe dengue. For the period between 2012 and 2015, controls were randomly selected from all nonfatal, dengue-positive patients hospitalized in reference health-care centers. We matched controls to cases by year and state in which care occurred (Santander or Valle del Cauca) to control by design for seasonality of the infection and temporal (endemic versus epidemic periods) and geographical heterogeneity of clinical practice.

Ethics

The Institutional Review Board of the Universidad Industrial de Santander granted ethics approval of the study with a waiver of informed consent for collection of anonymized case data. Access to medical records was authorized by each participating hospital. The staff of the study was trained in good clinical practices for data collection and management. The use of medical records was made according to the legislation regarding private documents in Colombia and the recommendations of national and international regulatory authorities.

Statistical analysis

Estimation in the presence of missing data might yield biased measures of association under a case-wise deletion approach. In addition, dropped observations due to missing data undermine the statistical power of any regression model, a critical consideration in the analysis of small samples as in the present study of fatal cases due to dengue. We conducted multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE)22 to fill in missing values of exposure variables ranging from 0.6% (for vomiting) to 32.7% (for hematuria) (Supplemental Table 1). More specifically, 39 (63%), 5 (8%), 13 (21%), and 5 (8%) of exposures had missing values in < 5%, 5–10%, 10–20%, and > 20% of patients, respectively. First, we built an imputation model that included all the variables assessed at hospital admission (socio-demographics, medical history, physical examination, and hemogram) for both cases and controls, and a subset of variables determined 48 hours before death using conditional imputation. Then, we assessed convergence of the MICE algorithm by evaluating trace plots of summaries of distributions (means and standard deviations) of imputed values over 100 iteration cycles and determined that a burn-in period of 10 iterations was appropriate to reach stationarity of chains, that is, absence of trend and regular fluctuations of the estimates parameters (Supplemental Figure 1). Finally, on acceptance of the final imputation model, we generated 40 imputed data sets (burn-in period of 10 iteration cycles), a number corresponding to the maximum percentage of missing data. Imputation was performed using the statistical software Stata/MP 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

We estimated mean differences and odds ratios (OR) contrasting cases and controls using univariate linear and conditional (by year-state strata) logistic regression for continuous and dichotomous variables measured at hospitalization, respectively. Those variables reaching a significance level less than or equal to 0.20 (P-value ≤ 0.20) were considered as candidate predictors for multivariate conditional logistic regression model building using a backward selection approach (retention criterion: P < 0.05; forcing the adjustment of all models by age, gender, disease’s duration at hospital admission, and health-care plan) with sequential reintroduction and testing of discarded candidates. Following this general approach, we built models for different sets of candidate predictors grouped according to the progressive steps that a physician follows during a standard clinical evaluation (from the anamnesis and physical examination to laboratory testing) and a composite model based on all clinical and laboratory data taken together. Furthermore, we evaluated the predictive accuracy of each model by estimating the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC). We additionally conducted a sensitivity analysis for the composite model implementing a case-wise deletion approach to check for consistency of main results. In the fatal cases, we estimated the proportion of clinical findings determined 48 hours before death. All estimation procedures based on imputed data, corrected counts, means, coefficients, and standard errors for the variability between imputations according to Rubin’s rules for combination.23

Results

We evaluated 110 fatal cases and 217 controls, in an approximated 1:2 ratio, matched by year and state of enrollment (Table 1). On average, cases were older than controls (35.0 versus 18.9 years; P < 0.001) and more likely to have access to a contributory (nonsubsidized) health-care plan (37.1% versus 11.9%; P < 0.001); however, cases and controls did not differ in the duration of the disease at hospital admission (4.9 versus 5.0 days; P = 0.706), time from hospitalization to death or length of hospital stay (2.4 versus 2.7 days; P = 0.554), or gender distribution (63.6% versus 57.1% male; P = 0.259). In addition, during hospitalization cases were more likely to receive more than 1 L of intravenous fluids (41% versus 29%, P = 0.049) and be prescribed with heparin (11.0% versus 1.8%), steroids (45.4% versus 5.7%), antibiotics (66.6% versus 14.8%), and vasopressors (85.3% versus 9.2%) than controls.

Cases were more likely to have a diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes or obesity, and to report a previous hospitalization, as compared with controls (Table 4). Furthermore, the burden of comorbidities was consistently higher among patients who referred to have been previously hospitalized compared with those without a previous hospitalization: 29.5% versus 15.2% for diabetes, 40.4% versus 13.8% for hypertension, and 27.2% versus 14.9% for obesity. At hospital admission the prevalence of rash, retro-ocular pain, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and minor hemorrhage was lower among cases than controls. On the other hand, cases were more likely to have major hemorrhage and clinical signs of cardiorespiratory and central nervous system involvement. Also, at admission, cases had lower hematocrit and higher white blood cells (WBCs) count but comparable platelet count than controls.

Table 4.

Main findings of the clinical examination and the hemogram at hospitalization, by case–control status

| Finding | Case (n = 110) | Control (n = 217) | OR/∆ (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 19.1 (17.4) | 3.0 (1.4) | 14.9 (4.30, 51.7) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 6.1 (5.5) | 3.0 (1.4) | 4.17 (1.02, 17.0) | 0.047 |

| Obesity | 11.3 (10.3) | 7.1 (3.3) | 3.38 (1.27, 9.00) | 0.015 |

| Asthma | 5.3 (4.8) | 11.1 (5.1) | 0.94 (0.32, 2.78) | 0.910 |

| Allergic disease | 6.6 (6.0) | 11.0 (5.1) | 1.19 (0.43, 3.31) | 0.741 |

| COPD | 3.1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0.989 |

| Hematologic disease | 2.0 (1.8) | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.39 (0.24, 24.4) | 0.461 |

| Previous surgery | 25.5 (23.2) | 33.3 (15.4) | 1.67 (0.90, 3.10) | 0.105 |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Any | 26.6 (24.1) | 24.5 (11.3) | 2.50 (1.32, 4.73) | 0.005 |

| Dengue related | 2.3 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.13 (0.29, 15.4) | 0.455 |

| Transfusion | 1.1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0.979 |

| Symptoms/signs | ||||

| Fever | 102.0 (92.7) | 205.6 (94.8) | 0.69 (0.25, 1.92) | 0.480 |

| Shivering | 30.9 (28.1) | 75.7 (34.9) | 0.73 (0.43, 1.22) | 0.229 |

| Rash | 22.6 (20.5) | 70.2 (32.3) | 0.54 (0.31, 0.96) | 0.035 |

| Retro-ocular pain | 8.3 (7.5) | 61.8 (28.5) | 0.20 (0.09, 0.46) | < 0.001 |

| Headache | 44.0 (40.0) | 131.8 (60.7) | 0.43 (0.27, 0.69) | 0.001 |

| Myalgia | 58.0 (52.7) | 154.9 (71.4) | 0.45 (0.27, 0.73) | 0.001 |

| Arthralgia | 51.6 (46.9) | 133.3 (61.4) | 0.55 (0.35, 0.89) | 0.015 |

| Hyporexia | 36.2 (32.9) | 65.1 (30.0) | 1.14 (0.69, 1.90) | 0.609 |

| Odynophagia | 8.2 (7.4) | 13.3 (6.1) | 1.23 (0.49, 3.06) | 0.661 |

| Asthenia | 58.2 (52.9) | 99.6 (45.9) | 1.33 (0.80, 2.19) | 0.269 |

| Adynamia | 62.0 (56.3) | 100.2 (46.2) | 1.51 (0.92, 2.46) | 0.104 |

| Physical discomfort | 70.8 (64.4) | 113.8 (52.4) | 1.64 (0.99, 2.69) | 0.051 |

| Nausea | 20.9 (19.0) | 68.1 (31.4) | 0.51 (0.29, 0.92) | 0.024 |

| Vomiting | 46.6 (42.3) | 124.5 (57.4) | 0.55 (0.34, 0.87) | 0.011 |

| Diarrhea | 23.4 (21.3) | 65.3 (30.1) | 0.63 (0.36, 1.09) | 0.098 |

| Abdominal pain | 48.4 (44.0) | 150.8 (70.0) | 0.35 (0.21, 0.56) | < 0.001 |

| Hemorrhage | ||||

| Minor | 38.0 (34.5) | 108 (50.0) | 0.53 (0.33, 0.86) | 0.010 |

| Major | 27.9 (25.4) | 32.0 (14.7) | 1.97 (1.09, 3.57) | 0.025 |

| Respiratory distress | 42.2 (38.4) | 11.6 (5.4) | 11.0 (5.39, 22.6) | < 0.001 |

| Edema (lower limbs) | 14.6 (13.3) | 10.3 (4.7) | 3.09 (1.33, 7.22) | 0.009 |

| Impaired consciousness | 71.7 (65.2) | 53.5 (24.6) | 5.72 (3.44, 9.53) | < 0.001 |

| Seizures | 9.1 (8.2) | 4.0 (1.8) | 4.77 (1.44, 15.9) | 0.011 |

| Wheezing | 7.1 (6.4) | 2.9 (1.3) | 5.91 (0.82, 42.6) | 0.078 |

| Rattles | 16.0 (14.6) | 7.5 (3.4) | 5.02 (1.61, 15.7) | 0.006 |

| Attenuated respiratory sounds | 28.3 (25.7) | 32.5 (15.0) | 1.96 (1.11, 3.48) | 0.020 |

| Basal dullness | 1.2 (1.1) | 4.1 (1.9) | 0.54 (0.06, 4.88) | 0.585 |

| Abdominal pain | 55.2 (50.1) | 123.5 (56.9) | 0.76 (0.48, 1.22) | 0.253 |

| Hepatomegaly | 21.4 (19.4) | 79.2 (36.5) | 0.42 (0.24, 0.75) | 0.003 |

| Splenomegaly | 5.1 (4.6) | 7.2 (3.3) | 1.44 (0.41, 5.05) | 0.568 |

| Plasma leakage | 42.4 (38.6) | 71.4 (32.9) | 1.28 (0.78, 2.09) | 0.324 |

| Jaundice | 17.6 (14.9) | 3.2 (1.5) | 12.7 (3.62, 44.8) | < 0.001 |

| Cyanosis | 22.4 (20.3) | 2.3 (1.1) | 24.2 (5.7, 103.7) | < 0.001 |

| Vital signs | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.0 (0.11) | 36.9 (0.06) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) | 0.458 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 120.8 (3.4) | 90.8 (1.4) | 30.0 (23.8, 36.3) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (rpm) | 30.2 (1.5) | 22.7 (0.6) | 7.5 (4.9, 10.1) | < 0.001 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | – | – | – | – |

| Systolic | 94.2 (2.8) | 102.1 (1.0) | −7.9 (−12.8, −3.1) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic | 55.6 (1.8) | 64.0 (0.8) | −8.4 (−11.8, −5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hemogram | ||||

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.5 (1.0) | 41.4 (0.6) | −3.9 (−5.9, −1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Log-platelet (count/mL) | 10.6 (0.1) | 10.5 (0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) | 0.344 |

| Platelet count < 100,000/mL | 15.0 (13.6) | 18.5 (8.5) | 1.70 (0.77, 3.73) | 0.186 |

| Log-WBC (count/mL) | 8.9 (0.1) | 8.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) | < 0.001 |

| WBC count < 4,000/mL | 21.5 (19.5) | 89.7 (41.3) | 0.34 (0.18, 0.65) | 0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR = odds ratio; WBC = white blood cells; ∆ = mean difference between cases and controls. Minor hemorrhage = petechiae, ecchymosis, gingivorrhagia, or epistaxis; major hemorrhage = hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, or hematuria; Consciousness impairment = lethargy, somnolence, irritability or agitation; Plasma leakage = clinical evidence of pleural effusion, ascites, or edema (facial, lower extremities, or generalized). Figures in each cell correspond to counts (percentage) and means (standard error) estimated using Rubin’s rules for combination.

In a multivariate model restricted to evaluate variables related to the medical history, (model 1) only the report of a previous hospitalization was independently associated to mortality (Table 5). In an alternative model that only considered clinical signs and symptoms (model 2), cases were less likely to report myalgia and abdominal pain but more likely to have respiratory distress, jaundice, and impaired consciousness than controls. In addition, higher heart rate and lower systolic blood pressure were independently associated with mortality in a model based exclusively on vital signs (model 3), whereas in a fourth model restricted to hemogram parameters, lower hematocrit and higher WBC count increased the likelihood of death.

Table 5.

Multivariate prediction models for mortality based on medical history, physical examination, and hemogram data at hospitalization

| Model* | OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Medical history | ||

| Previous hospitalization | 2.10 (1.03, 4.25) | 0.74 (0.67, 0.80) |

| Model 2: Signs/symptoms | ||

| Myalgia | 0.20 (0.08, 0.50) | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) |

| Abdominal pain | 0.36 (0.16, 0.79) | |

| Respiratory distress | 8.00 (2.58, 24.6) | |

| Impaired consciousness | 10.2 (3.81, 27.1) | |

| Jaundice | 8.85 (1.67, 46.9) | |

| Cyanosis | 20.5 (2.04, 205.2) | |

| Model 3: Vital signs | ||

| HR (per 10 bpm increment) | 1.79 (1.51, 2.12) | 0.91 (0.87, 0.94) |

| SBP (per 10 mmHg decrement) | 1.28 (1.06, 1.56) | |

| Model 4: Hemogram | ||

| Hematocrit (per 1% increment) | 0.92 (0.88, 0.96) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.89) |

| WBC (per 1,000/mL increment) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.21) | |

| Model 5: Composite | ||

| Age (per 10 year increment) | 2.45 (1.77, 3.41) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) |

| Retro-ocular pain | 0.23 (0.06, 0.96) | |

| Nausea | 0.29 (0.09, 0.94) | |

| Diarrhea | 0.19 (0.05, 0.68) | |

| Respiratory distress | 16.3 (4.11, 64.4) | |

| Impaired consciousness | 15.9 (4.22, 59.6) | |

| Jaundice | 32.2 (2.50, 414.1) | |

| HR (per 10 bpm increment) | 2.01 (1.55, 2.61) | |

AUC = area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve; CI = confidence interval; HR = heart rate (beats per minute); OR = odds ratio; SBP = systolic blood pressure (mmHg); WBC = white blood cells.

* All models adjusted by age, gender, duration of disease at hospital admission, and health-care plan.

To determine the joint contribution of clinical and laboratory data, candidate variables from medical history, physical examination, and hemogram were considered altogether for model building. From this selection process emerged a composite model (model 5) that retained retro-ocular pain, nausea and diarrhea as variables associated with a lower likelihood of mortality, and respiratory distress, impaired consciousness, jaundice, and higher heart rate as predictors of death (Table 5). In addition, age and affiliation to a contributory health plan were independently associated with mortality but these covariates did not modify the effect of any other predictor. This model had the highest predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.96, 0.99), being marginally better than the model based on signs and symptoms (AUC = 0.93; 95% CI: 0.90, 0.96) and significantly superior compared with the models based on medical history, vital signs, and hemogram parameters (AUC = 0.74, 0.91, and 0.84, respectively). The results from a complete case analysis (n = 245; 74 cases and 171 controls) applied to the composite model were consistent but less precise compared with those obtained from multiple imputation with the exception of retro-ocular pain that did not reach statistical significance.

Clinical findings in fatal cases 48 hours before death.

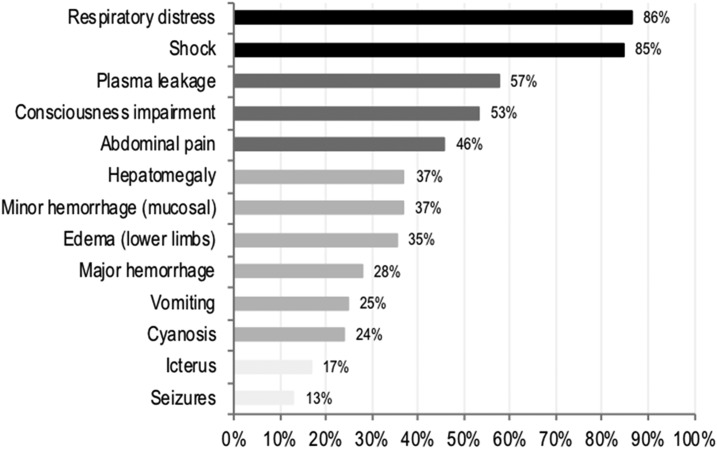

Respiratory distress and shock were the most frequently observed clinical findings 48 hours before death (86% and 85%, respectively), followed by signs of plasma leakage (57.0%), impaired consciousness (53.0%), and abdominal pain (46%) (Figure 1). Furthermore, the prevalence of respiratory distress and hypovolemic shock markedly increased among fatal cases during hospitalization from 38% to 86% and from 33% to 85%, respectively. Finally, respiratory distress and shock, if present at the time of hospitalization, tracked in most of the patients up to 48 hours before death (98% and 92%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Distribution of clinical findings 48 hours before death (n = 110).

Discussion

Dengue is one of the most rapidly spreading arbovirus globally and its incidence has increased dramatically in the last decades. In this study, the fatal cases were older, and they also had higher prevalence of comorbidities and history of prior hospitalization along with a higher incidence of manifestations of cardiorespiratory and central nervous system involvement compared with controls. Although cases and controls had different hemogram profiles at enrollment, these differences did not improve the prediction of dengue mortality once main clinical findings had been taken into account. Finally, among fatal cases the most frequent clinical findings observed 48 hours before death were respiratory distress, shock, plasma leakage, and impaired consciousness, which suggest that these markers of severe dengue are a good proxy for mortality.

We observed that fatal cases were on average older than controls and that a difference of 1 year of age increased independently the likelihood of mortality by about 10%. Often considered more frequent in children, dengue hemorrhage fever, severe dengue, and mortality are becoming more common among older adults as a consequence of the shifting patterns of infection and immunity.19,24–27 In a descriptive study of dengue mortality conducted in Colombia between 1985 and 2012, researchers reported the highest CFR among patients 65 years and older.10 This observation is consistent with the results of other case–control studies conducted in Asian and Latin American populations, in which older patients were at higher odds of death independent of socioeconomic status and severity of dengue.6,7,28 This age–mortality relationship might be explained by the larger number of coexistent diseases among older patients, result of both demographic and epidemiologic transitions in low- and middle-income countries.24–27

Past medical history of hospitalization and coexistent diseases were also associated with mortality before any clinical examination data were considered. Hypertension and diabetes but no other chronic comorbidities were more likely among fatal cases than controls in the crude analysis; however, after multivariate adjustment, only the history of a nonsurgery-related hospitalization independently increased the odds of death among patients. Hypertension but not diabetes has been previously reported to increase the likelihood of death in a small case–control study, although the authors provided no details about statistical adjustment.29 Two more case–control studies also conducted on Asian hospitalized patients did not find associations between hypertension, diabetes, or any other comorbidity and death,28,30 with the exception of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) being more prevalent among cases than controls in the elderly.28 Kuo et al.31 reported that chronic renal failure and pulmonary disease, but no hypertension or diabetes, increased the likelihood of mortality, independently of age, gender, and past history of dengue fever.

Our results seem to be at odds with those from Lee et al.28 and Kuo et al.,31 specifically regarding pulmonary disease; however, this discrepancy might be only apparent as long as previous hospitalization is a reasonable surrogate of an individual’s health status (as shown by our data) and therefore of risk for dengue complications and death. Underreporting of comorbidities due to lack of awareness is not uncommon in chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes32 and might be larger for less prevalent conditions or those not included in screening programs such as COPD. In this scenario, under the likely assumption of non-differential reporting of comorbidities among cases and controls at the time of hospitalization, the underestimation of any association with death would be less probable as awareness of diseases or health events such as hospitalization increase.

Regarding symptoms and clinical signs collected at the time of hospitalization, we observed that retro-ocular pain, nausea, and diarrhea were less prevalent among cases than controls, after adjustment for demographics and signs of severity. This finding coincides with other studies such as those from Thein in Singapore24 and Moraes in Brazil.6 The last author referred to those findings as “early signs of severity,” which might constitute proxies of a timely diagnosis, and therefore, their recognition could modify the course of the disease.

Respiratory distress independently and markedly increased the likelihood of death among dengue patients in our study. Pleural effusion and pulmonary edema have been previously associated with mortality in unadjusted case–control studies that exclusively included patients with severe dengue28,30 and acute respiratory failure, although relatively infrequent, is strongly related to mortality.33 Furthermore, nonspecific signs of severe plasma leakage have been reported more often among fatal than nonfatal cases.6,7,34 In our study, respiratory distress not only increased the likelihood of fatal outcomes when evaluated at enrollment, but also constituted the most prevalent finding 48 hours before death, which highlights the importance of systematically assessing and tracking early respiratory abnormalities during hospitalization.

Impaired consciousness and jaundice, signs of central nervous system and hepatic compromise, respectively, were also more prevalent in cases than controls at the time of hospitalization; however, because of the high uncertainty around the estimates of effect, the interpretation of their association with mortality should be conservative. Pang et al.35 found that in hospitalized patients, the evidence of severe organ involvement increased the likelihood of admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and specifically that concentrations of aminotransferases independently and significantly predicted death among ICU patients. Consistently, high bilirubin concentrations24 and hepatic failure have been reported as factors increasing the likelihood of death.6,30 Furthermore, neurologic abnormalities, ranging from restlessness to lethargy, have been associated with fatal outcomes in dengue,6,7,29,30 which confirms the previously described role of impaired consciousness as a predictor of progression to severity in patients with dengue infection.36

Blood pressure and heart rate at the time of hospitalization allowed discriminating fatal from nonfatal cases; however, in the composite model, after the inclusion of medical history, symptoms, and signs, only heart rate remained associated with mortality. An abnormal hemodynamic status not only identified dengue patients at a higher risk of admission to an ICU,35 but also has been associated with mortality.6,24,28,30,34 Hypovolemic shock at any time of hospitalization, whether or not related to massive hemorrhage, was more prevalent among fatal cases than controls in an unadjusted analysis by Lee et al.30 In a hospital-based case–control study, Thein et al.24 reported that at the time of hospital presentation fatal cases had higher heart rate than controls; however, no differences were observed in terms of blood pressure or the prevalence of dengue shock syndrome, and in multivariable analysis no hemodynamic parameter discriminated cases from controls. On the other hand, two studies using the Brazilian national surveillance system suggested that hemodynamic abnormalities increase the likelihood of death; however, from these reports is not possible to disentangle specific associations of hemodynamic parameters from other clinical findings on mortality.6,34 In this context, our results contribute to the understanding of the important and independent role of early hemodynamic status determination on mortality.

We also evaluated hemogram parameters in our study. Fatal cases had lower hematocrit and higher total WBC counts during the first day of hospitalization compared with controls; however, these parameters did not contribute to the discriminatory capability of clinical findings. In fact, a minimally adjusted model that included hematocrit and WBC performed as well as another that only considered self-reported previous hospitalization. Although widely evaluated in other studies,6,24,28–30,35 hemogram parameters measured early during the course of hospitalization did not consistently improve discrimination of fatal from nonfatal cases. For instance, Thein et al.24 reported that high WBC measured at the time of hospitalization increased threefold the likelihood of death, whereas Moraes et al.6 showed that a platelet count between 50,000 and 100,000 per mL but not lower than 50,000 per mL increased the likelihood of death. Although WBC was not independently associated with mortality in our study, the difference in WBC between cases and controls might be partially explained by a difference in the proportion of concurrent or superimposed bacterial infection as inferred from a higher prescription of antibiotics in cases than controls.

Our study has a number of strengths. First, we evaluated one of the largest series of dengue fatal cases that allowed us to test associations between early clinical findings and mortality with higher accuracy than other studies in the context of hospitalization. This was possible because death attributable to dengue is an event of mandatory notification to the national surveillance system, which allowed a comprehensive case ascertainment, particularly from highly endemic areas of Colombia, during a period in which the country experienced two large outbreaks of the disease. Second, dengue was diagnosed using the same serological criteria (IgM testing) for all controls and among cases, a high rate of laboratory positivity was achieved: nearly 87% were confirmed by RT-PCR or serology (NS1 or IgM) and the remaining were diagnosed based on autopsy findings highly compatible with the infection. It is worth noting that in a study of postmortem diagnosis of dengue, approximately, 62% of the cases defined based on clinical and pathology findings tested positive,37 which implies that nearly five fatal cases in our study (4.5%) might not have been certainly attributable to dengue, misclassification that might produce bias in either direction.

A case–control study design such as ours imposes additional limitations to causal inference because of selection bias, considering that controls (nonfatal cases of dengue) should have been ill enough to be admitted for hospitalization, that is, their probability of selection was related to the level of exposure (clinical and laboratory findings). In this circumstance, the estimates of the effect should be considered conservative because of the underestimation of the strength of the relationship between exposures and mortality. Furthermore, the determination of exposures based on medical records might introduce bias due to differential ascertainment and completeness of clinical and laboratory parameters at hospital admission between cases and controls. We approached this problem using multiple imputation under the missing-at-random (MAR) assumption that from a causal structure perspective is tenable considering the dependence of missing data of the exposures on a fully observed outcome.37 In addition, although the assumption that clinical and laboratory data that are MAR cannot be empirically tested, missingness on exposures (whether or not at random) would not result in biased estimates of effect under a complete case analysis. These considerations have direct implications to our results: First, that a complete case analysis would yield unbiased estimates of effect (specifically those based on ORs), and second, that the MAR assumption on which multiple imputation relies would be reasonably satisfied.37 The consistency of our results obtained from complete case and multiple imputation analyses suggests that our findings are robust to departures from the MAR assumption. Finally, although the relationship between early clinical and laboratory findings and dengue mortality might be prospectively assessed, such a design will not only require a longer period of data collection, but also might introduce additional bias to the extent that the systematic follow-up of patients influences decision-making in the clinical setting where the study is conducted.

In conclusion, older age, past medical history with emphasis on previous hospitalization, along with basic physical examination measurements such as heart rate and blood pressure determined early on the course of dengue infection might be used in the stratification of hospitalized patients regarding their risk of death. Our study reinforces the value of assessing relatively simple clinical variables during the initial evaluation and follow-up of dengue patients in clinical settings, and reconfirms the value of detecting syndromes compatible with severe dengue such as respiratory distress, shock, plasma leakage as appropriate proxies for lethality. Altogether, this study provides evidence to support the design of recommendations that might be easily adapted to current clinical guidelines in endemic countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to the staff of the nursing and epidemiology units supporting the study across sites, especially, from the Hospital Universitario del Valle and Hospital Universitario de Santander, as well as from all other health-care institutions of the Colombian health system that provided access to medical records. We also want to thank all the staff that supported data collection and handling, in particular, nurses Janeth Florez and Marinella Vanegas members of the Centro de Investigaciones Epidemiológicas (Universidad Industrial de Santander) and the AEDES Program (BPIN 2013000100011). This work would not have been possible without the support of the staff from the Pathology Departments of the Universidad Industrial de Santander and National Health Institute. This study was funded by the Colciencias thought grant No. 110256934490 (contract No. 606 of 2013) and the Universidad Industrial de Santander.

Note: Supplemental figure and table appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatt S, et al. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496: 504–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qian M-B, Zhou X-N, 2016. Global burden on neglected tropical diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 16: 1113–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson ME, Chen LH, 2015. Dengue: update on epidemiology. Curr Infect Dis Rep 17: 457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Dengue and Severe Dengue. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/index.html. Accessed March 7, 2017.

- 5.Tomashek KM, et al. 2016. Enhanced surveillance for fatal dengue-like acute febrile illness in Puerto Rico, 2010–2012. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10: e0005025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moraes GH, de Fátima Duarte E, Duarte EC, 2013. Determinants of mortality from severe dengue in Brazil: a population-based case-control study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 88: 670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liew SM, et al. 2016. Dengue in Malaysia: factors associated with dengue mortality from a national registry. PLoS One 11: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators , 2016. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388: 1459–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosso F, Vanegas S, Rodríguez S, Pacheco R, 2016. Prevalencia y curso clínico de la infección por dengue en adultos mayores con cuadro febril agudo en un hospital de alta complejidad en Cali, Colombia. Biomédica 36: 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaparro P, León W, Castañeda CA, 2016. Comportamiento de la mortalidad por dengue en Colombia entre 1985 y 2012. Biomédica 36: 125.27622802 [Google Scholar]

- 11.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators , 2016. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388: 1545–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamakaranage C, Rodrigo C, Samarawickrama S, Wijayaratne D, Jayawardane M, Karunanayake P, Jayasinghe S, 2012. Dengue hemorrhagic fever and severe thrombocytopenia in a patient on mandatory anticoagulation; balancing two life threatening conditions; a case report. BMC Infect Dis 12: 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pang J, Hsu JP, Yeo TW, Leo YS, Lye DC, 2017. Diabetes, cardiac disorders and asthma as risk factors for severe organ involvement among adult dengue patients: a matched case-control study. Sci Rep 7: 39872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carabali M, Hernandez LM, Arauz MJ, Villar LA, Ridde V, 2015. Why are people with dengue dying? A scoping review of determinants for dengue mortality. BMC Infect Dis 15: 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization , 2012. Global Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control 2012–2020. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan MIH, Anwar E, Agha A, Hassanien NSM, Ullah E, Syed IA, Raja A, 2013. Factors predicting severe dengue in patients with dengue fever. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 5: e2013014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yacoub S, Wills B, 2014. Predicting outcome from dengue. BMC Med 12: 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhaskar E, Sowmya G, Moorthy S, Sundar V, 2015. Prevalence, patterns, and factors associated with bleeding tendencies in dengue. J Infect Dev Ctries 9: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong A, Sandar M, Chen MI, Sin LY, 2007. Fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever in adults during a dengue epidemic in Singapore. Int J Infect Dis 11: 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization, Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases , 2009. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention, and Control. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organisation , 1997. Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever: Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control, 2nd edition, Vol. 40 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Buuren S, 2007. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 16: 219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin DB, 1987. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thein TL, Leo YS, Fisher DA, Low JG, Oh HML, Gan VC, Wong JGX, Lye DC, 2013. Risk factors for fatality among confirmed adult dengue inpatients in Singapore: a matched case-control study. PLoS One 8: e81060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ooi EE, Goh KT, Chee Wang DN, 2003. Effect of increasing age on the trend of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in Singapore. Int J Infect Dis 7: 231–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzmán MG, Alvarez M, Rodríguez R, Rosario D, Vázquez S, Valdés L, Cabrera MV, Kourí G, 1999. Fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba, 1997. Int J Infect Dis 3: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zagne SMO, Alves VGF, Nogueira RMR, Miagostovich MP, Lampe E, Tavares W, 1994. Dengue haemorrhagic fever in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a study of 56 confirmed cases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 88: 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee IK, Liu JW, Yang KD, 2008. Clinical and laboratory characteristics and risk factors for fatality in elderly patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg 79: 149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karunakaran A, Ilyas WM, Sheen SF, Jose NK, Nujum ZT, 2014. Risk factors of mortality among dengue patients admitted to a tertiary care setting in Kerala, India. J Infect Public Health 7: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee IK, Liu JW, Yang KD, 2012. Fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever in adults: emphasizing the evolutionary pre-fatal clinical and laboratory manifestations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo MC, Lu PL, Chang JM, Lin MY, Tsai JJ, Chen YH, Chang K, Chen HC, Hwang SJ, 2008. Impact of renal failure on the outcome of dengue viral infection. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva H, Hernandez-Hernandez R, Vinueza R, Velasco M, Boissonnet CP, Escobedo J, Silva HE, Pramparo P, Wilson E; CARMELA Study Investigators , 2010. Cardiovascular risk awareness, treatment, and control in urban Latin America. Am J Ther 17: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang CC, Liu SF, Liao SC, Lee IK, Liu JW, Lin AS, Wu CC, Chung YH, Lin MC, 2007. Acute respiratory failure in adult patients with dengue virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77: 151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campos KB, Amâncio FF, de Araújo VEM, Carneiro M, 2015. Factors associated with death from dengue in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil: historical cohort study. Trop Med Int Health 20: 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pang J, Thein TL, Leo YS, Lye DC, 2014. Early clinical and laboratory risk factors of intensive care unit requirement during 2004–2008 dengue epidemics in Singapore: a matched case-control study. BMC Infect Dis 14: 649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexander N, et al. European Union, World Health Organization (WHO–TDR) supported DENCO Study Group , 2011. Multicentre prospective study on dengue classification in four south-east Asian and three Latin American countries. Trop Med Int Health 16: 936–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westreich D, 2012. Berkson’s bias, selection bias, and missing data. Epidemiology 23: 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.