Abstract

Background:

Homelessness significantly affects health and well-being. Homeless adults often experience co-occurring and debilitating physical, psychological, and social conditions. These determinants are associated with disproportionate rates of infectious disease among homeless adults, including tuberculosis, HIV, and hepatitis. Less is known about sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevalence among homeless adults.

Methods:

We systematically searched 3 databases and reviewed the 2000–2016 literature on STI prevalence among homeless adults in the United States. We found 59 articles of US studies on STIs that included homeless adults. Of the 59 articles, 8 met the inclusion criteria of US-based, English-language, peer-reviewed articles, published in 2000 to 2016, with homeless adults in the sample. Descriptive and qualitative analyses were used to report STI prevalence rates and associated risk factors.

Results:

Overall, STI prevalence ranged from 2.1% to 52.5%. A composite STI prevalence was most often reported (n = 7), with rates ranging from 7.3% to 39.9%. Reported prevalence of chlamydia/gonorrhea (7.8%) was highest among younger homeless adult women. Highest reported prevalence was hepatitis C (52.5%) among older homeless men. Intimate partner violence, injection and noninjection substance use, incarceration history, and homelessness severity are associated with higher STI prevalence.

Conclusions:

Homeless adults are a vulnerable population. Factors found to be associated with sexual risk were concurrently associated with housing instability and homelessness severity. Addressing STI prevention needs of homeless adults can be enhanced by integrating sexual health, and other health services where homeless adults seek or receive housing and other support services.

Homelessness and housing instability are significant social and public health issues that adversely affect overall population health and well-being. According to the 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, in January 2015, 564,708 people were homeless on a given night.1 Most were in residential programs for homeless people, but 31% were unsheltered. Although one third were children and unaccompanied youth, most (68%) were adults 25 years or older. Evidence indicates the median age of the homeless adults is approaching 50 years, and those born between 1954 and 1965 experience higher rates of homelessness.2 Poor living conditions and limited access to health care systems are key factors that place homeless persons at an increased risk for communicable infections.3,4 Commonly reported individual and structural reasons for homelessness include lack of employment and money, drug and/or alcohol use, mental health problems, and early adverse childhood experiences.2,5 Histories of imprisonment and homelessness have shared risk factors that are associated with repeat episodes of homelessness (i.e., difficulty securing housing and employment and drug use).6 In a study of homeless and marginally housed adults, a lifetime history of having more than 100 sex partners was also associated with a history of imprisonment.6

The social determinants of health literature highlights how health outcomes are impacted by socioeconomic factors and how declines in health status are observed with lower levels of socioeconomic status.7 With the contributors to homelessness not solely being socioeconomic, the social, health, and human costs, as well as long-term solutions are complex. Compared with the general population, homeless persons experience increased disease morbidity and premature mortality that are associated with untreated or unmonitored chronic conditions, violence, or substance use.8–10 Higher rates of infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV, and hepatitis) are also reported.11 Life expectancy for homeless persons is reportedly 45 years,12 which is more than 30 years less than the life expectancy of the average American.13 In addition, homeless adults also experience significant disparate rates in dental problems, mental illness, and noninfectious chronic conditions.14

Research that has examined associations between infectious diseases such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and sexual or behavioral risk factors among homeless persons has often highlighted youth, who are at high risk for STIs.15–18 However, less is known about STI rates and the associated risks among homeless adults, or the extent to which STIs play a role in the health issues facing homeless adults.

We conducted a systematic review of literature specific to STI outcomes among homeless adults. We build upon previous work by focusing on STIs other than HIV (e.g., chlamydia [CT], gonorrhea [GC], syphilis, as well as hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus [HCV], and human papillomavirus [HPV]). We had 2 objectives with this review. First, we aimed to report the range of prevalence estimates for STIs among homeless adults. Second, we aimed to report the factors associated with STIs prevalence among homeless adults.

METHODS

Literature Search

The approach for this systematic review was informed by the PRISMA statement.19 The review was completed December 28, 2016. We initiated this review by searching PubMed, OVID, and Google Scholar for studies on STIs and homeless adults. Specific search terms used included the following: homeless (homeless, homelessness, transient living, street people), STIs/infections (syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, HPV, herpes, hepatitis), and rates (prevalence, incidence). Studies were included in the data set if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) English language, (2) published in a peer-reviewed journal, (3) conducted in the United States, (4) published between 2000 and 2016, (5) included homeless adults in the sample, and (6) reported STI prevalence rates among homeless adults. Forty-two articles that had study populations of adolescent youth (age <18 or 19–24 years) were analyzed and published separately.18 There was overlap among the age ranges between the studies of younger persons who are homeless (adolescent/youth, age <18 or 19–24 years) and studies of primarily older persons who are homeless (adults, age >18 years). To minimize possible duplication of results, studies with ages 18 to 24 years in their sample were included, if the mean sample age was greater than 25 years. Application of this ad hoc check resulted in 7 of the 8 studies in this data set having a mean age of greater than 30 years, which eliminated overlap and confirmed that the data set’s populations were primarily adults.

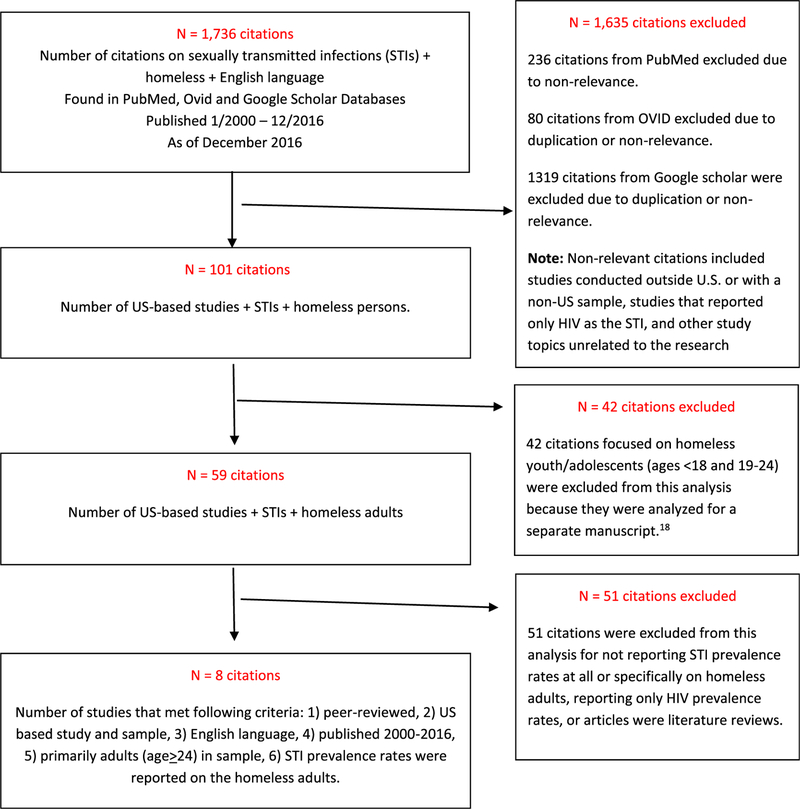

Our initial data set had 1736 citations published in English language that contained terms on STIs and homelessness. Most citations (1635) did not meet the criteria or were on unrelated topics (see Fig. 1). Of the 101 citations that remained, 42 citations were analyzed separately, as previously stated.18 The remaining 59 citations were eligible for full-text review. After full-text review, we excluded 51 articles for failing to meet key eligibility criteria; specifically, they lacked reported STI prevalence rates, reported only HIV prevalence rates, or were literature reviews. We used a data extraction table to record study details of articles that met eligibility criteria. The data extraction table included study population sociodemographics, methods, reported STI rates on homeless sample, homelessness severity, and results related to the studies’ STI findings. Full text review resulted in a final data set of 8 unique studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of a review on the prevalence of STI among homeless adults.

RESULTS

Of the 8 studies in this review, 5 had samples of women only,20–24 1 had men only,25 1 had a mixed-sex sample,26 and 1 study of medical records did not indicate sex.27 Table 1 summarizes the studies’ characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Studies Included in the Systematic Literature Review

| Publication | Study Characteristics | Data/Date Collection | Sample Characteristics | SDOH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canton et al.22 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 329) | Sample size (N = 329) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 28 shelters located in 4 New York City boroughs | Shelter | Type | Shelter | Type | |||

| Eligibility | ||||||||

| - Ages ≥18 y | STI screening | Single (n = 194) | Family (n = 135) | Single (n = 194) | Family (n = 135) | |||

| - Understand English/Spanish | Yes | |||||||

| - Bio specimen | Collection date | Age | Education | 58% | 45% | |||

| - Consent | Mid-2007 to mid-2008 | Mean | 41 y | 31 y | Employment | Not noted | ||

| Sex | Annual income | Not noted | ||||||

| Female | 100% | 100% | Arrest history | 49% | 36% | |||

| Race/ethnicity | Homeless severity/history | |||||||

| AA/black | 45.0% | 46.0% | Sheltered prior | 68% | 57% | |||

| His/Latino | 22.0% | 29.0% | Unsheltered prior | 29% | 20% | |||

| Oth/not rep | 32.0% | 25.0% | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Sing/nev mar | 60.0% | 52.0% | ||||||

| Sep/div/wid | 29.0% | 19.0% | ||||||

| Mar/com law | 11.0% | 28.0% | ||||||

| Orientation | Not noted | |||||||

| Grimley et al.26 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 416) | Sample size (n = 416) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 3 shelters that provided services to homeless | City A (n = 216) | City B (n = 200) | City A (n = 216) | City B (n = 200) | |||

| Eligibility | ||||||||

| - Ages 18–45 y | STI screening | |||||||

| - Bio specimen | Yes | Age, y | Education | |||||

| Collection date | Mean | 34.9% | 34.3% | <HS | 37.9 | 39.4 | ||

| April to June 2004 | Sex | HS | 39.5 | 43.9 | ||||

| Male | 65.5% | 60.2% | >HS | 22.5 | 16.7 | |||

| Female | 34.5% | 39.8% | Employment | Not noted | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | Annual income | |||||||

| Blk | 68.5% | 88.0% | <10,000 | 86.0 | 84.2 | |||

| W | 29.1% | 12.0% | 10,000+ | 9.7 | 13.3 | |||

| Other | 2.4% | — | >20,000 | 4.3 | 2.5 | |||

| Relationship status | Arrest history | Not noted | ||||||

| Mar | 24.0% | 20.0% | Homeless severity/history | Not noted | ||||

| Orientation | ||||||||

| Het. | 90.6% | 91.0% | ||||||

| Hom. | 2.9% | 5.0% | ||||||

| Bi. | 6.6% | 4.0% | ||||||

| Jenness et al.20 | Study design | Location | Sample size (n = 436) | Sample size (n = 436) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | New York City | Homeless | 54.7% (n = 238) | Homeless | 54.7% (n = 238) | |||

| Eligibility | STI screening | Age | Education | Not noted | ||||

| - Ages 18–50 y | No | 18–29 | 34.4% | Annual income | 76.9% | |||

| - Understand English/Spanish | Other: Questionnaire on STI diagnosis in the past year | 30–39 | 20.1% | <10 K | 24.6% | |||

| - Consent | 40–50 | 45.5% | ||||||

| - Opposite-sex vaginal or anal sex in the past year | Collection date | Sex | Arrest history | |||||

| 2006 – 2007 | Female | 100% | Homeless severity/history | Not noted | ||||

| - New York City residence | Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| AA/Blk | 70% | |||||||

| White | 9% | |||||||

| Hispanic | 19.2% | |||||||

| Other | 1.5% | |||||||

| Marital status | Not noted | |||||||

| Orientation | Not noted | |||||||

| Notoro et al.27 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 2279) | Sample size (n = 2279) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | Champaign County Christian Health Care Center in east central Illinois | Homeless (n = 122) | General (n = 2157) | Homeless (n = 122) | General (n = 2157) | |||

| Eligibility | ||||||||

| - Ages <18 y | ||||||||

| - Identified as homeless in medical record | STI screening | |||||||

| No | Age | Not noted | Education | Not noted | ||||

| Other: Medical records search | Sex | Not noted | Employment | Not noted | ||||

| Collection date | Race/ethnicity | Not noted | Annual income | Not noted | ||||

| Patient visits from 2004 to 2009 | Relationship status | Not noted | Arrest history | Not noted | ||||

| Marital status | Not noted | Homeless severity/history | Not noted | |||||

| Orientation | Not noted | |||||||

| Nyamathi at al.24 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 621) | Sample size (n = 621) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | Shelters, and outreach areas in southwest Los Angeles, CA | Age | Education | |||||

| Eligibility | ||||||||

| - Ages ≥18 y | STI screening | Range | 15–65 y | Mean | 11.2 y | |||

| - Homeless | Yes* | Mean | 34.3 y | <HS | 43.8% | |||

| - Consent | Participants were referred post-HCV screening by CHMC | Sex | HS | 34.8% | ||||

| >HS | 21.4% | |||||||

| Collection date | Female | 100% | Employment | |||||

| 1995–1997 | Race/ethnicity | Unemployed | 88.0% | |||||

| AA/black | 53.5% | Veterans | 35.0% | |||||

| White | 22.1% | Annual income | ||||||

| Latina/Hispanic | 23.0% | SSI/SSDI | 90.6% | |||||

| Marital status | AFDC | 72.8% | ||||||

| Sing/nev mar | 43.3% | Food Stamps | 40.5% | |||||

| Sep/div/wid | 30.0% | WIC | 89.7% | |||||

| Mar/com law | 25.4% | Family/friends | 14.2% | |||||

| Orientation | Not noted | Jail/prison history | Not noted | |||||

| Homeless severity/history | Not noted | |||||||

| Stein and Nyamathi25 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 198) | Sample size (n = 198) | ||||

| Case-control | Skid Row area of Downtown Los Angeles County, CA | Age | Education | |||||

| Range | 18–63 y | Range | 4–12 y | |||||

| Eligibility | STI screening | Mean | 43.8 y | Median | 12 y | |||

| - Ages 18–65 y | Yes* | Sex | Employment | |||||

| - Live in Skid Row | Participants were referred post-HCV screening by CHMC | Male | 100% | Full/part time | 16.3% | |||

| - Tested for HCV by identified CHMC | Race/ethnicity | Unemployed | 77.1% | |||||

| Collection date | AA/Blk | 70% | In school | 8.4% | ||||

| 2002–2003 | W | 19% | Annual income | Not noted | ||||

| L/H | 11% | Jail/prison history | ||||||

| Marital status | # of times: Range, 1–2; μ = 1.83 | |||||||

| Sing/nev mar | 59% | Homeless severity/history | ||||||

| Sep/div/wid | 36% | # of times Range, 0–60; mean, 4.63 | ||||||

| Mar/com law | 3% | # of years Range, 0–23; mean, 4.85 | ||||||

| Intimate relation | 29% | |||||||

| Orientation | ||||||||

| MSM | 4% | |||||||

| Teruya et al.23 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 1331) | Sample size (n = 1331) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 63 shelters, and outreach areas in southwest Los Angeles county, San Fernando Valley and Pasadena, CA | Age | Education | |||||

| Eligibility | STI screening | Mean | 33.0 y | Mean | 11.2 y | |||

| - Ages ≥18 y | No | Sex | Employment | |||||

| - Homeless | Collection date | Female | 100% | Full/part time | 10.0% | |||

| -Consent | 1994–1996 | Race/ethnicity | Annual income | |||||

| AA/Blk | 48.7% | Public assistance | 72.0% | |||||

| W | 20.9% | From family/friends | 10.0% | |||||

| L/H | 30.4% | Incarceration history | 45.0% | |||||

| Marital status | Homeless severity/history | |||||||

| Mar/partnered | 28% | Multiple homeless episodes | 42.0% | |||||

| Orientation | Not noted | |||||||

| Vijayaraghavan et al.21 | Study design | Locations | Sample size (n = 329) | Sample size (n = 329) | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 28 shelters located in 4 New York City boroughs | IPV | IPV (n = 147) | No IPV (n = 169) | IPV (n = 147) | No IPV (n = 169) | ||

| Eligibility | STI screening | |||||||

| - Ages ≥18 y | Yes | Age | Education | |||||

| - Understand English/Spanish | Collection date | Mean | 39.9 y | 36.1 y | <HS | 46.9% | 48.5% | |

| - Bio specimen | Mid-2007 to mid-2008 | Sex | HS | 20.7% | 27.8% | |||

| - Consent | Female | 100% | 100% | >HS | 23.7% | 32.4% | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 4.1% | 5.9% | ||||||

| AA/black | 41.5% | 50.3% | ||||||

| His/Latino | 26.5% | 23.1% | ||||||

| Oth/not rep | 27.9% | 20.7% | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Mar/com law | 19.2% | 17.3% | ||||||

| Orientation | Not noted | |||||||

AA indicates African American; Bi, bisexual; Blk, black; Com, common; Div, divorced; Het, heterosexual; Hom, homosexual; His, Hispanic; HS, high school; Oth, other; L/H, Latino/Hispanic; Mar, married; MSM, men who had sex with men; Rep, represented; SDOH, Social Determinants of Health; Sep, separated; Sing, single; W, white; WIC, Women, Infants, and Children; Wid, widow/er.

Study Locations

Reported locations included one study of 2 unidentified cities in Alabama (n = 1); areas of Los Angeles County, San Fernando Valley, and Pasadena, California (n = 3); Champagne, Illinois (n = 1); and areas in New York City boroughs (n = 3). None were from the Census Mountain, West North or South Central, South Atlantic, or New England regions. All studies were conducted in urban areas.

Setting, Recruitment, and Inclusion Criteria

Most studies were conducted at homeless shelters and outreach venues (n = 6). One study recruited from a clinical health care center. The medical record study used data from a free health care clinic. Recruitment was primarily accomplished by study staff approaching participants at the settings (n = 6). In one study, potential participants were referred to the study by a specified community health medical clinic (CHMC). Recruitment was conducted in English, and 3 studies recruited in Spanish and English. Core eligibility across studies were age (≥18 years), homelessness (per study definition), and a consent. Provision of a biological specimen was the next most common eligibility criterion across the studies (n = 4), followed by geographic location (n = 2).

Data Collection Methods and Incentives

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews by study staff using a survey or questionnaire (n = 6) that ranged from 5 to 60 minutes. One study used audio computer-assisted self-interview survey in addition to the face-to-face interview. Incentives for participation, when provided, ranged from a $12 food coupon to $50 cash.

Participant Demographics

Participants across the studies were 18 to 65 years old. The reported mean ages ranged from 31 to 43.8 years. Studies with a younger mean age sample tended to have women only and women staying in shelters (see Table 1). The study with men only had the oldest mean age (43.8 years; range, 18–63 years). Most participants across the studies were African American/black, with proportions ranging from 45% to 88%. Studies (n = 2) with the most African American/black participants had men only or higher proportions of men (68.5%–88%). Studies (n = 2) that had men only or higher proportions of men also had more white participants (12%–29.1%). Studies that reported on women in single and family shelters, and those who experienced intimate partner violence (IPV; n = 2) had the largest proportions of Hispanic/Latina (22%–29%) and “Oth/not rep” identified (20.7%–32%) women. Education was reported by most studies (n = 6), with approximately half of participants across the studies completing high school/12 or more years of education. Six studies reported on marital status, with marriage/common law rates ranging from 20% to 25%. Marriage and partnerships were more often reported for women (11%–28%) than for men (3%), and for younger than older women. More women living in family shelters (28%) or who experienced IPV reported being married or common law married (19.2%). Most of the studies did not report on sexual orientation. Of the 2 that did, one study with a mix-sex sample reported approximately 9% of their sample identified as homosexual or bisexual. The second study of all men reported that 4% of their sample were men who had sex with men.

STI Prevalence

The STI prevalence estimates of studies are in Table 2. Four studies included biological STI testing as part of their assessment protocol.21,22,25,26 One study reported diagnosed STIs identified in medical records.27 Three studies reported participants’ self-reported diagnosed STIs.20,23,24 Overall, STI prevalence across the studies ranged from 2.1% to 52.5%. A composite variable representing multiple STIs or any STI diagnosed was the most frequent way prevalence was reported (n = 7), with rates ranging from 7.3% to 39.9%. Chlamydia (n = 2), GC (n = 2), and hepatitis (HCV and nonspecified; n = 2) were the most frequently reported infections. Rates of HCV were the highest and ranged from 9.8% to 52.5%. Rates of CT ranged from 6.4% to 6.7%, and rates of GC ranged from 0.3% to 3.2%. Syphilis prevalence was lowest (1.1%) and reported by one study.

TABLE 2.

Summary of STI Prevalence Estimates Across Studies Included in the Systematic Review

| Publication | STI Screening | STI Prevalence | Associated Risk Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canton et al.22 | Laboratory test/method | STI prevalence rate | Sexual risk | |||

| Urine | Shelter Type | IPV | ||||

| Blood | Total (n = 329) | Single (n = 194) | Family (n = 135) | Substance use disorder | ||

| Oral swab | HIV | 1.8% (6) | 3.3% | — | Posttraumatic stress disorder | |

| STIs screened for in the study | GC | 0.3% (1) | — | — | Childhood trauma | |

| CT | CT | 4.6% (15) | — | — | Psychiatric conditions | |

| GC | Any | 6.4% (21) | 2.1% | 7.8% | Arrest history | |

| HIV | ||||||

| Single (n = 194) | Family (n = 135) | |||||

| Prior STI testing | 95% | 99% | ||||

| Self-reported STI history | ||||||

| 33.7% (111/329) | ||||||

| Grimley et al.26 | Laboratory test/method | Sample size (n = 416) | Alcohol use before sex | |||

| Urine | STI prevalence rate of sexually active participants | Drug use before sex | ||||

| Blood | Overall rate = 16.4% (49/296) | Sex exchange for drug, money, shelter | ||||

| Oral swab | City A (n = 140) | City B (n = 156) | Condom use, always inconsistent and never | |||

| STIs screened for in the study | Rate | 12.9% (18) | 19.9% (31) | Sex with main and other partner(s) | ||

| CT | CT | 6.4% (9/140) | 15% (23/156) | |||

| GC | GC | 5.0% (7/140) | 3.2% (5/156) | |||

| Syp | Syp | 0.08% (1/133) | 1.4% (2/142) | |||

| HIV | HIV | 0.07% (1/136) | 0.06% (1/149) | |||

| STI prevalence rate of participants not sexually active | ||||||

| Overall rate = 5.2% (6/114) | ||||||

| City A (n = 71) | City B (n = 43) | |||||

| Rate | 7% (5) | 2.3% (1) | ||||

| CT | 4.2% (3/71) | 2.3% (1/43) | ||||

| GC | 2.8% (2/71) | — | ||||

| Self-reported STI history | ||||||

| City A | City B | |||||

| 32.6% (69/216) | 36.1% (72/200) | |||||

| Jenness et al.20 | Laboratory test/method | Sample size (n = 436) | Noninjection and injection substance use | |||

| Blood | Homeless (n = 238) | Binge alcohol history | ||||

| STIs screened for in the study | Self-reported STI history | 39.9% (95/238) | Unprotected vaginal or anal sex, 5+ partners | |||

| HIV | Sex exchange | |||||

| Arrest history | ||||||

| Incarceration history of partner | ||||||

| Notoro et al.27 | Laboratory test/method | Sample size (n = 2279) | Psychiatric conditions | |||

| Not noted | Homeless (n = 122) | General (n = 2157) | Other health conditions | |||

| Medical records | STIs | 8.4% (10) | 5.8% (126) | |||

| STIs screened for in the study | Hep | 9.8% (12) | 2.5% (54) | |||

| Not noted | ||||||

| Diagnosed STIs | ||||||

| Any STIs, unspecified Hep | ||||||

| Nyamathi at al.24 | Laboratory test/method | Sample size (n = 621) | Sexual risk | |||

| Not noted | Self-reported STI history | IPV | ||||

| STIs screened for in the study | 6 mo prior: range 1–2; µ = 1.50 | Substance, alcohol, injection drug use, history | ||||

| Not noted | STI prevalence not noted | Physical and sexual abuse history | ||||

| Reproductive health and care history | ||||||

| HIV test and return | ||||||

| Health status and health care service assessment | ||||||

| Mental health assessment and hospitalization history | ||||||

| Emotional and problem-focused coping | ||||||

| Stein and Nyamathi25 | Laboratory test/method | Sample size (n = 198) | Non-IDU substance use and alcohol history | |||

| Blood | STI prevalence rate | IDU substance use behaviors | ||||

| STIs screened for in the study | HCV positive = 52.5% (104/198) | Risky sexual behaviors | ||||

| HCV | HCV negative = 47.5% (94/198) | Incarceration | ||||

| Self-reported STI history | STI history | |||||

| 6 mo prior: range, 0–4; μ = 0.50 | ||||||

| Teruya et al.23 | Laboratory test/method | Sample size (n = 1331) | IPV | |||

| Not noted | STI Prevalence via self-reported STI history by race/ethnicity | Substance, alcohol, injection drug use, history | ||||

| STIs screened for in the study | n | % | Physical and sexual abuse history | |||

| Not noted | AA/Blk | 648 | 37 | Reproductive health and care history | ||

| W | 278 | 32 | Mental health assessment and hospitalization history | |||

| L/H | 405 | 13 | Health status and health care service assessment | |||

| Total | 1331 | 29 | ||||

| Vijayaraghavan et al.21 | Laboratory test/method | Prevalence Rate of one or more Diagnosed STIs | Sexual risk | |||

| Urine | Total: 31.6% (104/329) | IPV | ||||

| Blood | IPV (n = 147) | Lifetime history of substance and alcohol use | ||||

| Oral swab | 40.7% (59) | Foster care and juvenile detention history | ||||

| STIs screened for in the study | No IPV (n = 169) | Childhood trauma | ||||

| CT | 1 < STIs | 25.9% (45) | Psychiatric conditions | |||

| GC | ||||||

| HIV | ||||||

AA indicates African American; Blk, black; Hep, hepatitis; IDU, injection drug user; L/H, Latin(a/o)/Hispanic; Syp, syphilis; W, white.

STI Prevalence, Demographics, and Risk Factors

Sex and Age.

Homeless women in single (individual) shelters had the lowest STI rates (2.1%) when compared with women in family shelters (7.8%),22 and when their STI rates were compared with the those of homeless women in other studies.20,21,23 Women in single shelters were older compared with women in the family shelters of the same study (41 vs. 33 years)22 and older compared with women in other studies.20,21,23 Incidentally, more women in family shelters reported sexual activity in the 3 months before the assessment compared with women in the single shelter (63% vs. 44%). Hepatitis, when reported,25,27 more frequently affected homeless men. In the medical record study, prevalence estimates of nonspecified hepatitis among homeless men was 9.8%.27 In a study that screened homeless men living on skid row, HCV prevalence was 52.5% and highest among the older men.25

Race/Ethnicity.

All studies reported participants’ race/ethnicity except for one,27 and 2 studies reported STI rates by participants’ race/ethnicity. In one study, STI rates were highest among African American/black (37%) and white (32%) women, and lowest among Hispanic/Latina women (13%).23 In another study, STI history was highest and not significantly different among Hispanic/Latina (39.8%), African American/black (33.3%), and “other” identified women (30%) compared with white women (14.7%).23 On the contrary, another study indicated that white women were more likely to have had a recent STI and an HIV test compared with African American/black and Hispanic/Latina women.24 However, the finding did not include an STI rate, and it was in the study’s discussion section.

Place/Location.

One study screened sexually active patrons of homeless shelters in 2 unidentified cities (A and B) in Alabama for CT, GC, syphilis, and HIV.26 The authors examined STI prevalence by “city” after controlling for 3 background variables, which differed (e.g., race/ethnicity, sexual activity in prior 2 months, and drug use before sex). Overall STI prevalence for sexually active adults was 16.4%, but it was significantly higher in city B (19.9%) than in city A (12.9%). No additional significant differences were reported; however, more men in city B (14.3%) than in city A (4.18%) tested CT positive. Interestingly, among the participants who reported not having sex in the 2 months before the study (22%), the overall STI prevalence was 5.2%, with more participants testing positive in city A (7%) than in city B (2.3%).

Sexual Activity and Sexual Risk.

Three of the 5 studies that examined sexually activity or sexual risk reported associations with STIs among homeless persons. In the study of women in shelters, more women in the family shelters (63%) reported sexual activity than those in single shelters (44%). Women in the family shelters also had higher rates of STIs (7.8 vs. 2.1).22 In the city comparison study (B, 19.9%; A, 12.9%), participants in city B engaged in more sexual activity (P < 0.05), and participants in city A reported higher rates of drug use before engaging in sex (P < 0.001). Incidentally, 22% of participants reported not engaging in sexual activity in the 2 months before the study. However, the STI rate was 5.2% (6/114).26 In a study that examined predictors of STIs and testing among homeless women, risky sexual behaviors were predictive of a recent STI history.24 Although not specific to the homeless subpopulation, a study that examined unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) as a risk factor found that STI diagnoses were significantly associated with sex exchange (P < 0.01) and multiple sex partnerships (P < 0.01).20

IPV and Childhood or Adult Physical/Sexual Abuse.

Two of the 3 studies assessed histories of IPV and childhood or adult physical/sexual assault and examined associations with STI prevalence.21–23 In a study that examined health outcomes of homeless women, higher rates of STIs were found among women with an IPV history (40.7%) compared with women with no IPV history (26.9%).21 In the study of women in shelters, more than 40% of women reported an IPV history. Although no associations were found between STI prevalence and IPV history, self-reported STI history was associated with a history of childhood sexual abuse.22 Associations between STIs and abuse or assault were not reported in a study that examined health disparities among ethnically diverse women. However, approximately one third of women experienced child sexual assault (30%) or adult physical assault (34%), and a greater proportion of white women reported experiencing both forms of assault (41% and 47%, respectively).23

Mental Health/Psychiatric.

Four studies assessed mental health history or symptoms.21–24 Two studies examined associations between mental health problems and STIs. More women in the single shelters compared with women in the family shelters reported lifetime histories of psychotic symptoms (25% vs. 3%) and Axis I disorders (63% vs. 46%). More women in single shelters also reported active (e.g., current) psychotic symptoms (20% vs. 0%) and Axis I disorders (40% vs. 16%) at the time of the interview. Also, both mental health indicators were associated with having a history of STIs.22 In a different study, emotion-focused coping was associated with reported STIs in the 6 months before assessment, and problem-focused coping was associated with HIV testing.24

Substance Use.

Seven of the 8 studies used diverse methods to analyze and report substance use (alcohol, injection and noninjection drugs) history, and activity. Three studies examined associations between substance use and STIs. Among homeless men, HCV status correlated with noninjection substance use history, injection behaviors, and non–needle-sharing behaviors (e.g., sharing straws for cocaine inhalation, razors, and toothbrushes).25 In the single/family shelter study, confirmed STI testing was associated with active (e.g., current) substance use disorder, which more women in the single shelter experienced (11% vs. 9%).22 Among women in the STI predictor study, crack cocaine use and risky sexual behaviors were predictive of having an STI in the 6 months before study participation.24

The remaining 4 studies reported linkages between substance use and other factors or risks behaviors. In a study that examined ethnically different homeless women, African American/black women reported more drug/alcohol problems and higher STI rates. However, no associations between reported drug/alcohol problems and STI rates were reported.23 Women with IPV histories compared with women with no IPV histories were more likely to report histories of substance use (49.3% vs. 26.8%), STIs (40.7% vs. 25.9), and a history of homelessness (75.9% vs. 61.3%).21 In the UAI study, women who reported UAI were more likely to report being homeless, using drugs/binge use alcohol, and exchanging sex for money/drugs.20 In the city comparison study, “drug use before sex” was 1 of the 3 variables that differed across cities A and B. However, none of the variables were confounders, and the city that had more participants who reported drug use before sex had fewer STIs.26

Incarceration/Jails/Prison.

Two of the 4 studies that measured incarceration history (i.e., arrest, jail, prison), also examined the associations with STIs. Among women in single and family shelters, self-reported STI history was more common among women in the sample who had an arrest history. Also, more women in the single shelters (49%) reported an arrest history compared with women in the family shelters (36%).22 In the study of homeless men on skid row, 83% of the men had an incarceration history, which was 1 of 5 factors associated with HCV infection.25

In 2 studies that measured incarceration history, one reported on a sexual risk that was associated with STI prevalence and the other reported ethnic differences in arrest history. Specifically, in the study of high-risk heterosexual women, homelessness and having a last sex partner who was incarcerated were 2 of several factors associated with UAI.20 In the second study, African American/black (53%) and white women (51%) were more likely to have had a history of incarceration compared with Hispanic/Latinas (27%).23

Homelessness Severity.

Four studies measured homeless severity by assessing number episodes of homelessness, number of years homeless, or prior shelter stays. A single study of homeless men specifically examined the relationship between homeless severity and prevalence. The study of men only reported homelessness severity; specifically, more and longer episodes of homelessness were associated with HCV infection.25 The findings of the other studies were not as clearly linked or reported. Women with IPV history (75.9%) compared with those without (61.3%) were more likely to have had a history of homelessness. As noted earlier, higher rates of STIs were reported among women with IPV histories.21 In a study that examined health disparities among women, 42% of the women experienced multiple episodes of homelessness, with more white women affected (46%) compared with African American/black (41%) and Hispanic/Latinas (42%). In addition, more white women (33%) reported living on the streets in the 30 days before study participation compared with African American/black (10%) and Hispanic/Latinas (9%) women. However, STIs were highest for African American/black women (37%), though similar to white women (32%), and both were twice that of Hispanic/Latinas (13%).23 In the shelter study, more women in the single shelters (68%) reported a history homelessness compared with women in the family shelters (57%). However, women in single shelter (2.1%) had the lowest STI prevalence compared with women in the family shelters (7.8%).22

DISCUSSION

This literature review reports STI prevalence rates found among homeless adults in the United States, as determined by biological testing or self-reported STI history. Consistent with US surveillance data,28 CT (6.4%–6.7%) and GC (0.3%–3.2%) were the most frequently reported STIs. Rates of HCV were the highest, affected older adults, and ranged from 9.8% to 52.5%. Lowest STI prevalence was for syphilis (1.1%), reported by one study. None of the other STIs (i.e., herpes, HPV, genital warts, trichomoniasis) were reported among the 8 studies in this review.

Consistent with previous literature,4,6,9,10,13 substance use/abuse history, incarceration, trauma, and negative health outcomes associations were found among homeless adults. This review of literature focused on homeless adults, sought to describe associations between STIs and risk factors. Homeless women who experience IPV had the highest prevalence of one or more STI diagnoses, and STIs were also associated with any histories of abuse and assault. With regard to substance use, all but one study measured and reported substance use as a contributing factor to homelessness or STI prevalence. For women, IPV histories increased the likelihood of having a substance use history, and both IPV and substance use histories were associated with STI prevalence. For men with HCV, substance use history seems to be a primary risk for STIs. Mental health symptoms or disorders are also associated with STI risk and outcomes for women, but the indicators were not reported for men. Four studies reported incarceration as a risk factor for STI rates or STI history among women, and predictive of HCV for homeless men.

Findings also indicate differences in risk behaviors and STI outcomes among homeless women with children. Compared with women in family shelters, women in single shelters were older, less sexually active, and more likely to have experienced lifetime and active mental health symptoms, as well as lifetime and active substance use disorder. In contrast, the high prevalence of confirmed STIs among women in family shelters, patrons who use homeless shelters, and unsheltered adults highlights “settings” where STI preventive efforts can also be beneficial. The factors associated with reported STI prevalence among homeless single adult men and women, and homeless adults with families indicate a need for sensitively tailored prevention interventions that address specific vulnerabilities.

There are limitations to this review, including the exclusion of unpublished evaluative and practice-based reports. We used specific criteria and relied on peer-reviewed publications, which may have limited the findings. Methods of assessing STI prevalence varied (e.g., biological sample, self-report, and medical records), adding to limited comparability. Prevalence reporting varied from individual STI rates to STI composite variables, again adding to limited comparability. Self-reporting is vulnerable to underreporting or over reporting, and it is unknown if the STIs diagnosed in the medical records were acute or lifetime. There is limited geographical diversity among the studies. Although the studies spanned from the East (Alabama) to the West coasts (California), there were no studies from the Mountain, West North and South Central, South Atlantic, or New England census regions, and none of the studies were conducted in rural or suburban areas where homelessness is also noted.29

Challenges to health and well-being such as infectious and chronic diseases morbidity, partner violence, past trauma, substance use, and mental health are exacerbated by lack of stable housing.3,4,10 The findings of this review highlight the limited data on the topic of STIs and homeless adults, as well as the risks and co-occurring conditions associated with STI rates among homeless adults. Screening for STIs offered as part of services for homeless adults would assist in identifying new and repeat infections. Health Care for the Homeless clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers that address the needs of homeless persons already incorporate HIV and HCV screening as part of their standard of care services. Testing for STIs may be more symptom based, and incorporating STI screening with other health and social services could minimize missed opportunities. Testing for STIs, treatment, and medical management can be challenging when housing instability is a primary concern, and even more with complex comorbid conditions. These findings are limited to STI estimates and correlates with those estimates. Data are needed regarding optimal strategies for STI prevention service provision for homeless adults with diverse interpersonal and family configurations, shelter circumstances, and homeless severity, as well as recovery or harm reductive, and physical and mental health needs. Prevention efforts informed with such data can enhance the likelihood of improved health outcomes, whereas efforts to support, stabilize, and rapidly and permanently house vulnerable adults are in progress.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Sources of Funding: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henry M, Shivji A, de Sousa T, et al. The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Report, (2015). Available at: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf. Accessed 2016

- 2.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in highincome countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014; 384:1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. Can Med Assoc J 2001; 164: 229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang SW, Aubry T, Palepu A, et al. The health and housing in transition study: A longitudinal study of the health of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. Inter J Public Health 2011; 56:609–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Toole TP, Conde-Martel A, Gibbon JL, et al. Where do people go when they first become homeless? A survey of homeless adults in the USA. Health Soc Care Community 2007; 15:446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL. Revolving doors: Imprisonment among the homeless and marginally housed population. Am J Public Health 2005; 95:1747–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakefield SE, Baxter J. Linking health inequality and environmental justice: Articulating a precautionary framework for research and action. Environ Justice 2010; 3:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrow S, Zimmer R. Transitional housing and services: A synthesis. Paper presented at: The I998 National Symposium on Homelessness Research; October 29, 1998; Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O’Connell JJ, et al. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126:625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, et al. Mortality among homeless adults in Boston: Shifts in causes of death over a 15-year period. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:189–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang SW, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian FG, et al. Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2005; 29:311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connell JJ. Premature mortality in homeless populations: A review of the literature, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc. Report, (2005). Available at: http://sbdww.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/PrematureMortalityFinal.pdf. Accessed 2016.

- 13.Xu L, Carpenter-Aeby T, Aeby VG, et al. A systematic review of the literature: Exploring correlates of sexual assault and homelessness. Trop Med Surgery 2016; 4:212 Available at: http://www.esciencecentral.org/journals/a-systematic-review-of-the-literature-exploring-correlatesof-sexual-assault-and-homelessness-2329-9088-1000212.php?aid=77404. Accessed 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggett TP, Singer DE, Rao SR, et al. Food insufficiency and health services utilization in a national sample of homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26:627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyamathi AM, Christiani A, Windokun F, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection, substance use and mental illness among homeless youth: A review. AIDS 2005; 19(suppl 3):S34–S40. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Abstract/2005/10003/Hepatitis_C_virus_infection,_substance_use_and.7.aspx. Accessed 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall BD, Kerr T, Shoveller JA, et al. Homelessness and unstable housing associated with an increased risk of HIVand STI transmission among street-involved youth. Health Place 2009; 15: 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beharry MS. Health issues in the homeless youth population. Pediatr Ann 2012; 41:154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caccamo A, Kachur R, Willams SP. Narrative review: STDs and homeless youth—what do we know about STD prevalence and risk? Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44:466–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenness SM, Begier EM, Neaigus A, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and sexually transmitted diseases in high-risk heterosexual women. Am J Public Health 2011; 101:745–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayaraghavan M, Tochterman A, Hsu E, et al. Health, access to health care, and health care use among homeless women with a history of intimate partner violence. J Comm Health 2011; 37:1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caton CL, El-Bassel N, Gelman A, et al. Rates and correlates of HIVand STI infection among homeless women. AIDS Behav 2012; 17:856–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teruya C, Longshore D, Andersen RM, et al. Health and health care disparities among homeless women. Women Health 2010; 50:719–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyamathi AM, Stein JA, Swanson JM. Personal, cognitive, behavioral, and demographic predictors of HIV testing and STDs in homeless women. J Behav Med 2000; 23:123–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein JA, Nyamathi A. Correlates of hepatitis C virus infection in homeless men: A latent variable approach. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004; 75: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimley DM, Annang L, Lewis I, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among urban shelter clients. Sex Transm Dis 2006; 33: 666–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Notaro SJ, Khan M, Kim C, et al. Analysis of the health status of the homeless clients utilizing a free clinic. J Comm Health 2012; 38: 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2015 Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Alliance to End Homelessness. Fact sheet: questions and answers on homelessness policy and research—Rural homelessness 2010. Available at: http://www.endhomelessness.org/library/entry/fact-sheet-rural-homelessness. Accessed May 19, 2017.