Abstract

Expression of cytochrome P450s (P450s) is regulated by epigenetic factors, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNAs through different mechanisms. Among these factors, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to play important roles in the regulation of gene expression; however, little is known about the effects of lncRNAs on the regulation of P450 expression. The aim of this study was to explore the role of lncRNAs in the regulation of P450 expression by using human liver tissues and hepatoma Huh7 cells. Through lncRNA microarray analysis and quantitative polymerase chain reaction in human liver tissues, we found that the lncRNA hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha antisense 1 (HNF1α-AS1), an antisense RNA of HNF1α, is positively correlated with the mRNA expression of CYP2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4 as well as pregnane X receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR). Gain- and loss-of-function studies in Huh7 cells transfected with small interfering RNAs or overexpression plasmids showed that HNF1α not only regulated the expression of HNF1α-AS1 and P450s, but also regulated the expression of CAR, PXR, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). In turn, HNF1α-AS1 regulated the expression of PXR and most P450s without affecting the expression of HNF1α, AhR, and CAR. Moreover, the rifampicin-induced expression of P450s was also affected by HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1. In summary, the results of this study suggested that HNF1α-AS1 is involved in the HNF1α-mediated regulation of P450s in the liver at both basal and drug-induced levels.

Introduction

Cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s) are monooxygenases responsible for the metabolism of most clinically used drugs (Nair et al., 2016). Significant interindividual variability in P450-mediated drug metabolism leads to various responses to drugs in clinical practice (Zanger and Schwab, 2013). Factors contributing to changes in P450 expression and function account for the interindividual variability in P450-mediated drug metabolism, including genetic, epigenetic, physiologic, pathologic, and environmental factors (Zhou et al., 2009; Zanger et al., 2014; Tracy et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017). Uncovering the molecular mechanisms in the regulation of P450 expression would therefore be beneficial to making therapies more effective and drugs safer.

Genetic polymorphism constitutes an important mechanism affecting the expression and functions of P450s but can only explain a proportion (15%–30%) of the interindividual differences among global populations (Ingelman-Sundberg et al., 2007; Pinto and Dolan, 2011). Epigenetic mechanisms are also important for the regulation of P450 expression, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNAs (Peng and Zhong, 2015; Tang and Chen, 2015). Both DNA methylation and histone modifications regulate the expression of P450s at a transcriptional level, whereas noncoding RNAs can influence P450 expression at either the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level. Depending on size, a noncoding RNA can be grouped as either small noncoding RNA [<200 nucleotides (nt)], including approximately 22-nt microRNA (miRNA), or long noncoding RNA (lncRNA, >200 nt). Regulation of P450s by miRNAs has been well documented through either direct or indirect interactions between miRNAs and the 3′-untranslated regions of the P450 mRNAs (Tsuchiya et al., 2006; Pan et al., 2009) or their regulatory nuclear receptor mRNAs (Yu et al., 2016); however, the regulation of P450 expression by lncRNAs is still being investigated.

LncRNAs can act as either activators or repressors in the regulation of gene expression by directly binding to transcriptional factors or recruiting chromatin-remodeling complexes. In some cases, lncRNAs recruit histone modification enzymes such as WD repeat domain 5/myeloid-lymphoid leukemia protein complexes to promoter regions and activate the transcription of target genes by driving histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (Wang et al., 2011). In other situations, lncRNAs inactivate the transcription of target genes by recruiting polycomb repressive complex-2 and increasing histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in promoter regions (Kaneko et al., 2014). Moreover, lncRNAs can also affect the post-transcriptional and translational regulation of target genes by influencing the splicing process of mRNA or binding to translation factors and ribosomes (Ma et al., 2013).

Expression of P450s can also be regulated by lncRNAs. Recently, we reported that the lncRNAs hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha antisense 1 (HNF1α-AS1) and HNF4α-AS1, together with nuclear receptors, constitute a regulatory network to control the basal and drug-induced expression of P450s in HepaRG cells (Chen et al., 2018). In the current study, we provide a systematic analysis to determine the role of HNF1α-AS1 as well as its neighbor HNF1α in the regulation of P450 expression in human liver samples and hepatocarcinoma Huh7 cells. We found that HNF1α-AS1 under the control of HNF1α is involved in the regulation of basal and drug-induced expression of numerous P450s as well as the transcriptional regulator pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents.

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Corning Inc. (Armonk, NY). Opti-MEM was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (51985034; Carlsbad, CA). TriPure isolation reagent was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Penicillin and streptomycin mixture, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and other chemical reagents were provided by Solarbio Science & Technology Co. (Beijing, China). Primers, SYBR Select Master Mix, small interfering RNA (siRNAs) for HNF1α (A01003), siRNAs for HNF1α-AS1 (HSS178564), and control siRNAs (A06001) were provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes were purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). HNF1α expression plasmid was purchased from Genecopoeia (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), HNF1α-AS1 plasmid was provided by GeneChem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HNF1α primary antibody (ab174653; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primary antibody (60004-1-Ig; Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and secondary antibodies (SA00001-1, SA00001-2; Proteintech) were used in Western blot analysis.

Human Liver Tissues.

The uses of the liver tissues were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University and written consent was obtained from the participating patients. A total of 43 human liver tissues were collected and prepared as described in our previous studies (He et al., 2016; Nie et al., 2017). Information about the 43 liver samples used in this study is provided in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4, including age, sex, race, and pathologic condition.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

Human hepatoma cell line Huh7 is a commercially available cell line frequently used as an in vitro system for the of study gene regulation. Huh7 cells were provided by the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (cat. no. TcHu182; Shanghai, China) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin mixture. For gene silencing or overexpression experiments, Huh7 cells were transiently transfected with specific siRNAs or expression plasmids using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, Huh7 cells were allowed to grow for up to 24 hour on six-well plates and reached 80%–90% confluence prior to transfection. Then, 40 pmol of siRNAs targeting HNF1α, HNF1α-AS1, or control siRNAs were mixed with RNAiMAX reagent in minimum essential medium and added into the culture medium. In overexpression studies, 2.5 μg of plasmids were used for each well. At 24 hours after transfection, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and incubated for another 24 hours. For drug induction studies, transfected cells were incubated with rifampicin (10 μM) or DMSO (0.1%, v/v) for 24 hours before harvested.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Total RNA from liver tissues or cultured cells was isolated using the TriPure isolation reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Basel, Switzerland). The quality and concentrations of RNAs were analyzed by a Nanodrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For mRNA expression analysis, total RNAs were reversely transcribed using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) reactions were performed by a SYBR method as previously described (Nie et al., 2017). Primers are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

LncRNA Microarray Analysis.

Total RNAs from the selected liver tissues were isolated using TRIzol reagent (10296028; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the expression profiles of lncRNAs were determined by lncRNA microarray chips (4 × 180K; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Data were extracted with Feature Extraction software 10.7 (Agilent Technologies) and raw data were normalized using the Quantile algorithm, GeneSpring Software 11.0 (Agilent Technologies). LncRNA microarray and data analysis were performed by Shanghai Biotechnology Corporation (Shanghai, China).

Western Blot Analysis.

Total proteins of the liver tissues or treated cells were prepared using a RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0), and protein concentrations were determined using a previously described method (Nie et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017). Protein samples were separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes. After being blocked for 2 hours in 5% nonfat milk, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies for HNF1α or GAPDH overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: anti-HNF1α (1:1000; rabbit polyclonal) and anti-GAPDH (1:10000; mouse monoclonal). The membranes were then incubated in horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies in blocking buffer for 2 hours and visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence method. GAPDH protein was used as a loading control.

Statistical Analysis.

All in vitro experiments with Huh7 cells described here were performed as three independent experiments. Data are shown as the means ± S.D. Statistical significances between groups were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test using SPSS version 17.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to assess the correlations of gene expression between HNF1α-AS1 and P450s as well as nuclear receptors in the 43 liver tissue samples using Prism 6 from GraphPad (La Jolla, CA).

Results

LncRNA Expression Profiles in Liver Tissues.

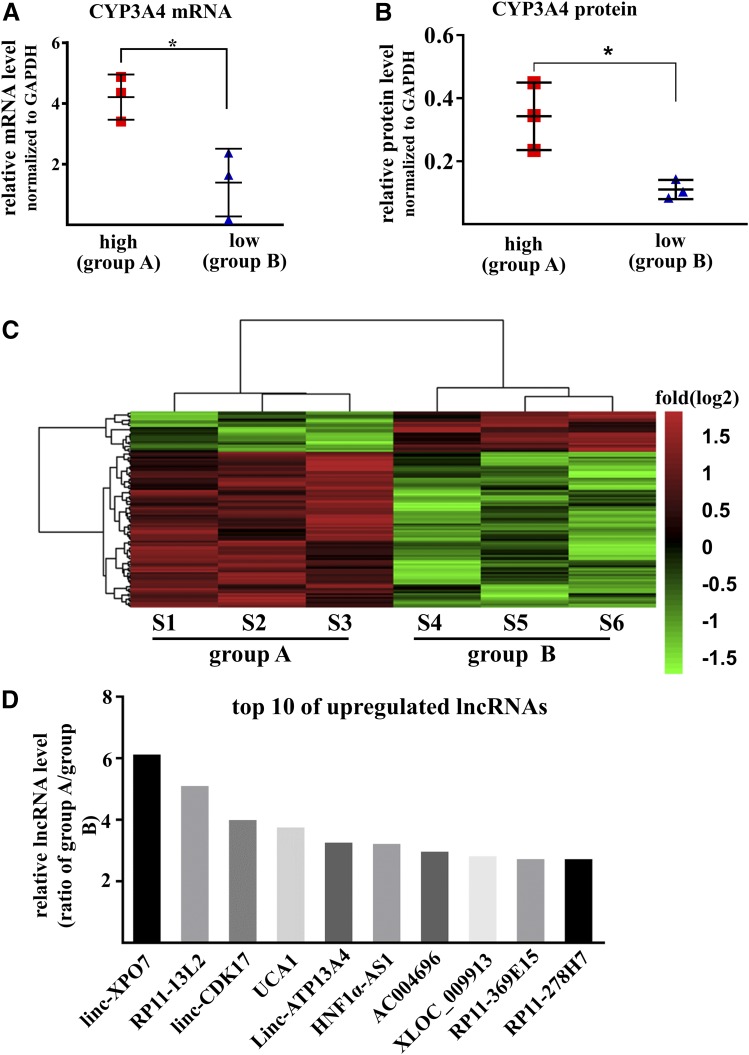

The expression levels of mRNA and protein of CYP3A4 in liver tissues were measured by qPCR and Western blot. Two groups were set according to the expression levels of CYP3A4: Group A contained three samples with a high level of CYP3A4 expression for both mRNA and protein and group B contained three samples with a low level of CYP3A4 (Fig. 1, A and B). The differences in mean mRNA and protein between groups A and B were 3.0- and 3.1-fold, respectively. Expression profiles were then analyzed in each group using a microarray assay specific for lncRNAs. A total of 112 lncRNA transcripts were identified as differently expressed between the two groups (fold difference >2.0, P< 0.05, Fig. 1C). Among these, 89 lncRNA transcripts were higher in group A than in group B, whereas 23 transcripts were lower. Among the top 10 increased lncRNAs in group A, lncRNA HNF1α-AS1 was ranked at sixth with a 3.3-fold difference (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

LncRNA expression profiles in liver tissues. (A) The mRNA levels of CYP3A4 in six liver tissues subjected to lncRNA microarray. (B) The protein levels of CYP3A4 in six liver tissues subjected to lncRNA microarray. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D., *P < 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. (C) Heat map of the expression profiles of lncRNAs in six liver tissues with fold changes in log2 scale. Colors represent the higher (red) or lower (green) expression of lncRNAs. (D) The top 10 upregulated lncRNAs in group A, which contained three samples with high levels of CYP3A4.

Evolutionary Conservation of HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1 DNA Sequences.

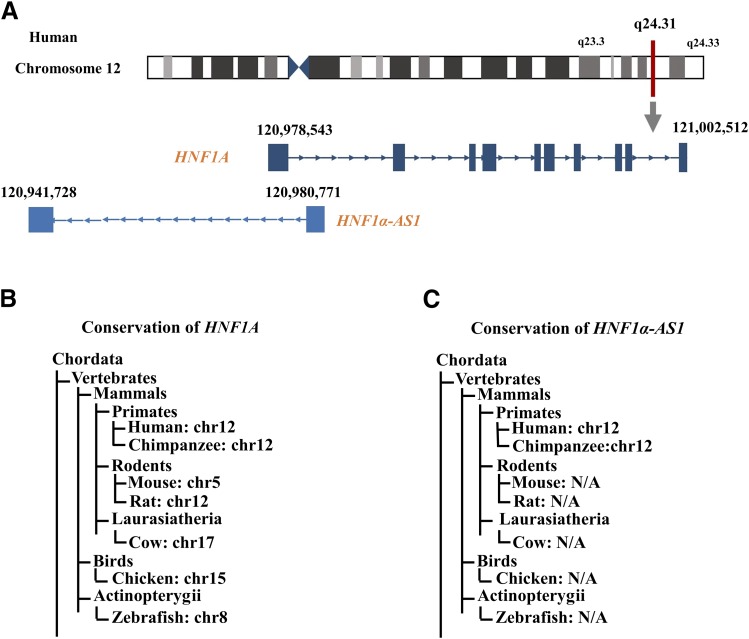

The HNF1α-AS1 gene is located at chromosome 12 between 120,941,728 and 120,980,771 in the annotated Human GRCh38/hg38 Genome and has a genomic sequence of 39.04 kb spanning two exons and 1 intron on the antisense strand (Fig. 2A). In the 3′-direction, the next gene encodes HNF1A at chromosome 12 between 120,978,543 and 121,002,512 in the Human GRCh38/hg38 Genome and has a genomic sequence of 23.97 kb spanning 10 exons and 9 introns on the sense strand. The genomic locus of HNF1A and HNF1α-AS1 genes forms a typical pair of sense coding genes and neighbor antisense noncoding gene. Analysis of the conservation levels of the DNA sequences of HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1 was performed using HomoloGene from NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene/459), UCSC genomic browser (www.genome.ucsc.edu), and NONCODE (www.noncode.org). The results indicated that the human DNA sequences of HNF1α are highly conserved with those of other mammals (approximately 90%) and birds (approximately 75%) as well as fish (zebrafish, approximately 60%) (Fig. 2, B and C), indicating its probable importance in physiologic processes across the species. However, the human HNF1α-AS1 sequence showed a much lower level of conservation, having been conserved only within mammals (>60%) and showing no conservation in birds and fish (Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 2.

DNA sequence conservation of HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1 across various species. (A) Genomic location of the HNF1A and HNF1α-AS1 genes in the Human GRCh38/h38 Genome. (B and C) Conservation levels (% identity) of the entire gene sequences of HNF1A (B) and HNF1α-AS1 (C) among species in comparison with human. The sequences are derived from the NCBI and NONCODE databases. NA, not available.

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of HNF1A and HNF1α-AS1 RNAs.

The protein encoded by the HNF1A gene is a well-studied transcription factor controlling the expression of numerous liver-specific genes. A specific tissue distribution pattern of HNF1A mRNA was retrieved from the RNA-Seq Expression Data GTEx in 53 tissues from 570 donors (GTEx Consortium, 2013), which showed relatively high expression levels in the stomach, liver, pancreas, small intestine, colon, and kidney, the major organs in the gastrointestinal tract (Supplemental Fig. S1A). A very similar tissue distribution pattern in the gastrointestinal tract organs was also found for HNF1α-AS1 (Supplemental Fig. S1B), indicating that HNF1α-AS1 is expressed in the same organs as HNF1α. These results suggested that HNF1α may control general physiologic processes for gastrointestinal functions, whereas HNF1α-AS1 is possibly involved in physiologic processes for gastrointestinal functions in a more species-specific manner in mammals. These results further supported the value of examining the roles of HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1 in the regulation of drug-metabolizing P450 enzymes.

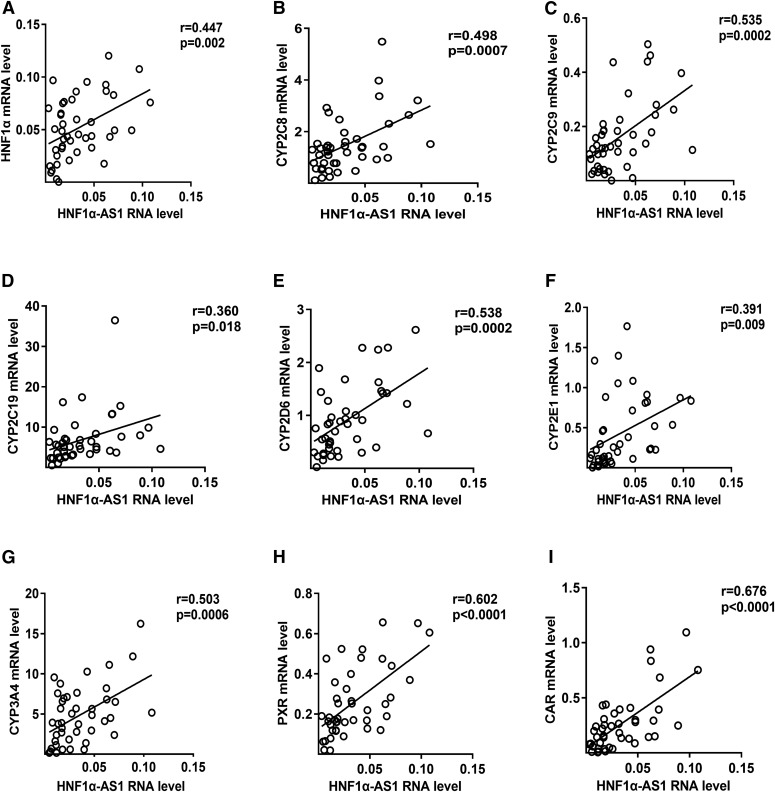

Correlations between HNF1α-AS1 and P450s as well as Transcriptional Regulators in Liver Tissues.

To further study the relationships between HNF1α-AS1 and P450s as well as transcriptional regulators in human liver, the RNA levels of HNF1α-AS1, HNF1α, P450s (CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4), and transcriptional regulators (PXR, CAR, and AhR) were measured in 43 liver tissues using qPCR, and the correlations between them were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Fig. 3; Supplemental Fig. S2; Supplemental Table S2). The results indicated that the RNA levels of the target genes presented considerable individual differences among the 43 samples (Supplemental Fig. S2) and the correlations between different mRNAs were varied (Supplemental Table S2). Specifically, the expression of HNF1α-AS1 RNA showed a statistically significant correlation with the expression of HNF1A mRNA (Fig. 3A, r = 0.447, P = 0.002) and major P450s examined, including CYP2C8 (Fig. 3B, r = 0.498, P = 0.0007), 2C9 (Fig. 3C, r = 0.535, P = 0.0002), 2C19 (Fig. 3D, r = 0.360, P = 0.018), 2D6 (Fig. 3E, r = 0.538, P = 0.0002), 2E1 (Fig. 3F, r = 0.391, P = 0.009), and 3A4 (Fig. 3G, r = 0.503, P = 0.0006) as well as PXR (Fig. 3H, r = 0.602, P < 0.0001) and CAR (Fig. 3I, r = 0.676, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 3.

Correlations of the RNA level of HNF1α-AS1 with that of HNF1α (A), CYP2C8 (B), 2C9 (C), 2C19 (D), 2D6 (E), 2E1 (F), 3A4 (G), PXR (H), and CAR (I) in 43 human liver tissue samples. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were calculated by two-tailed Pearson’s correlation analysis.

HNF1α Regulates the Expression of HNF1α-AS1, P450s, and Nuclear Receptors in Huh7 Cells.

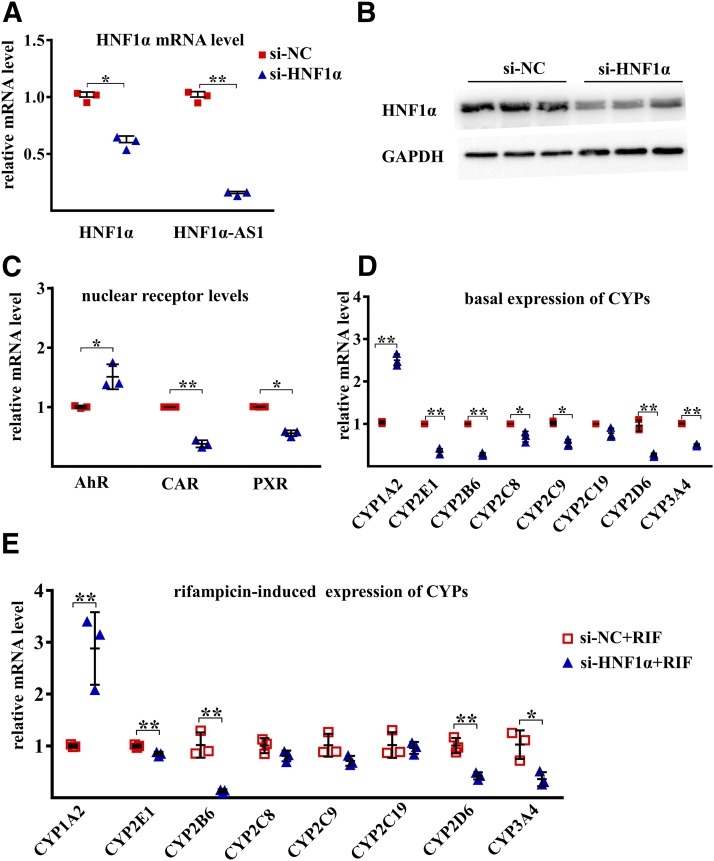

To uncover the impact of HNF1α on the transcriptional expression of HNF1α-AS1, P450s, as well as transcriptional regulators, silencing and overexpression of HNF1α were performed in Huh7 cells. A decrease in HNF1α mRNA and protein was confirmed after siRNA knockdown of HNF1α (Fig. 4, A and B). A decrease in HNF1α-AS1 (10% of the control) was also observed after knocking down the expression of HNF1α (Fig. 4A). In addition, the mRNA levels of CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4, as well as CAR and PXR, were also decreased in the HNF1α knockdown cells, whereas the expression of CYP1A2 and AhR was increased (Fig. 4, C and D). Moreover, knockdown of the expression of HNF1α also reduced the induction fold of CYP2B6, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4 by rifampicin but increased the induction of CYP1A2 (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Effects of HNF1α knockdown on the mRNA expression of the studied genes. (A) mRNA expression of HNF1α and RNA level of HNF1α-AS1 in siRNA negative control (si-NC) and siRNA HNF1α (si-HNF1α) transfected Huh7 cells. (B) Protein level of HNF1α in control si-NC- and si-HNF1α-transfected Huh7 cells. (C) Impact of HNF1α knockdown on the expression of AHR, CAR, and PXR mRNAs. (D) Impact of HNF1α knockdown on the basal expression of P450 mRNAs. (E) Impact of HNF1α knockdown on the rifampicin-induced expression of P450 mRNAs. Data points from three independent experiments are shown as dots along with the mean ± S.D., *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 in comparison of si-HNF1α with the si-NC group by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

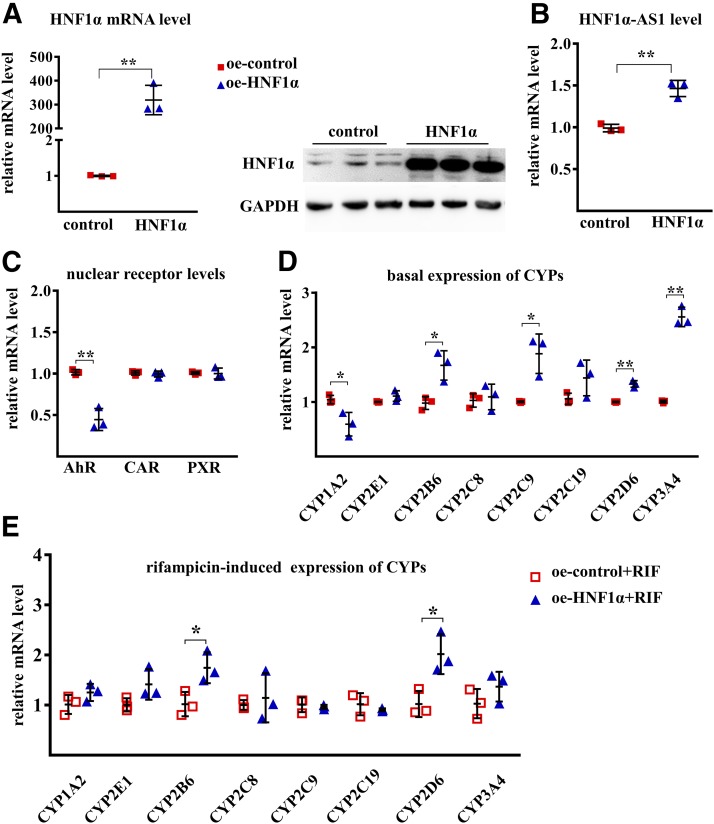

Overexpression of HNF1α mRNA and protein levels was confirmed by transfection of an expression plasmid containing the HNF1A gene (Fig. 5A). An increase in HNF1α-AS1 (Fig. 5B), as well as CYP2B6, 2C9, 2D6, and 3A4 (Fig. 5D), was found in the cells with overexpression of HNF1α in comparison with the control plasmid, whereas a decrease in CYP1A2 and AHR mRNA expression was observed (Fig. 5, C and D). The induction of CYP2B6 and 2D6 by rifampicin was also increased by HNF1α overexpression (Fig. 5E). These findings suggested that the alterations of HNF1α expression resulted in changes of basal and rifampicin-induced expression of major P450s via changes of HNF1α-AS1 and the transcriptional regulators PXR, CAR, and AhR.

Fig. 5.

Effects of HNF1α overexpression on the mRNA levels of the studied genes. (A) mRNA and protein levels of HNF1α in control and HNF1α-overexpressing (oe) Huh7 cells. (B) Impact of HNF1α overexpression on the expression of HNF1α-AS1 RNA in control and HNF1α-overexpressing Huh7 cells. (C) Impact of HNF1α overexpression on the expression of AHR, CAR, and PXR mRNAs. (D) Impact of HNF1α overexpression on the basal expression of P450 mRNAs. (E) Impact of HNF1α overexpression on the rifampicin-induced expression of P450 mRNAs. Data points from three independent experiments are shown as dots along with the mean ± S.D., *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 in comparison of overexpressing HNF1α with the control group by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

HNF1α-AS1 Regulates the Expression of P450s and PXR, but Not HNF1α, CAR, and AhR.

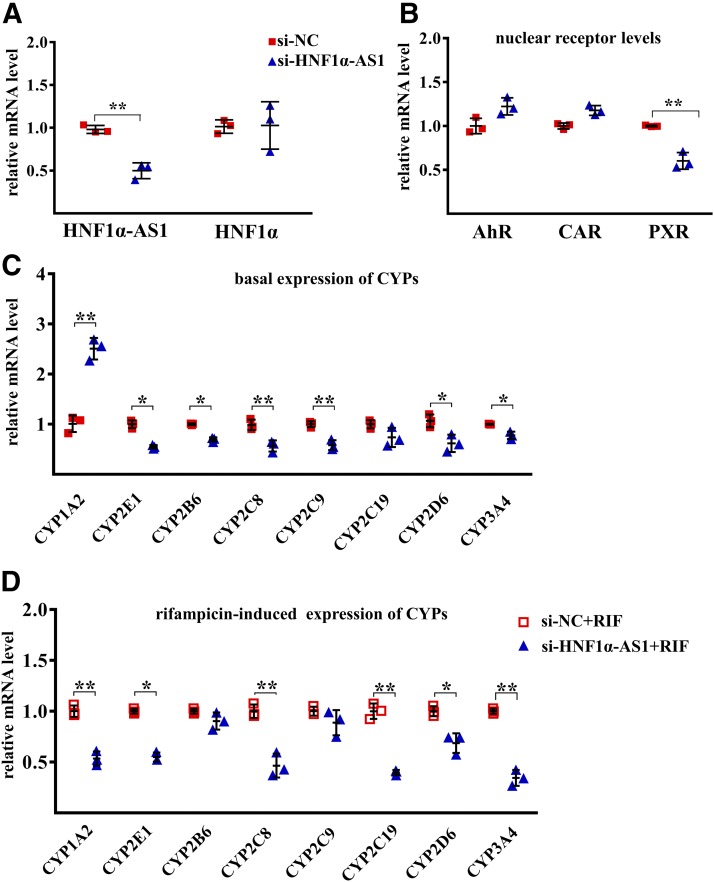

To explore the role of HNF1α-AS1 in the regulation of P450s and transcriptional regulators, RNA interference and overexpression were performed in Huh7 cells by using transient transfection of siRNAs or expression plasmids of HNF1α-AS1. SiRNA treatment showed the knockdown of HNF1α-AS1 to approximately 50% of siRNA control (Fig. 6A). After knockdown of HNF1α-AS1 expression, no alteration was observed for the mRNA levels of HNF1α, AhR, or CAR (Fig. 6, A and B), whereas the expression of PXR mRNA as well as the mRNAs of CYP2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4 was reduced, whereas that of CYP1A2 was increased (Fig. 6, B and C). The induction of most CYPs by rifampicin was also decreased after knockdown of HNF1α-AS1, including CYP1A2, 2C8, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4 (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Effects of HNF1α-AS1 knockdown on the mRNA expression of the studied genes. (A) Expression levels of HNF1α-AS1 and HNF1α in siRNA negative control (si-NC) and siRNA HNF1α-AS1(si-HNF1α-AS1)-transfected Huh7 cells. (B) Impact of HNF1α-AS1 knockdown on the expression of AHR, CAR, and PXR mRNAs. (C) Impact of HNF1α-AS1 knockdown on the basal expression of P450 mRNAs. (D) Impact of HNF1α-AS1 knockdown on the rifampicin-induced expression of P450 mRNAs. Data points from three independent experiments are shown as dots along with the mean ± S.D., *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 in comparison of si-HNF1α-AS1 with the control si-NC by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

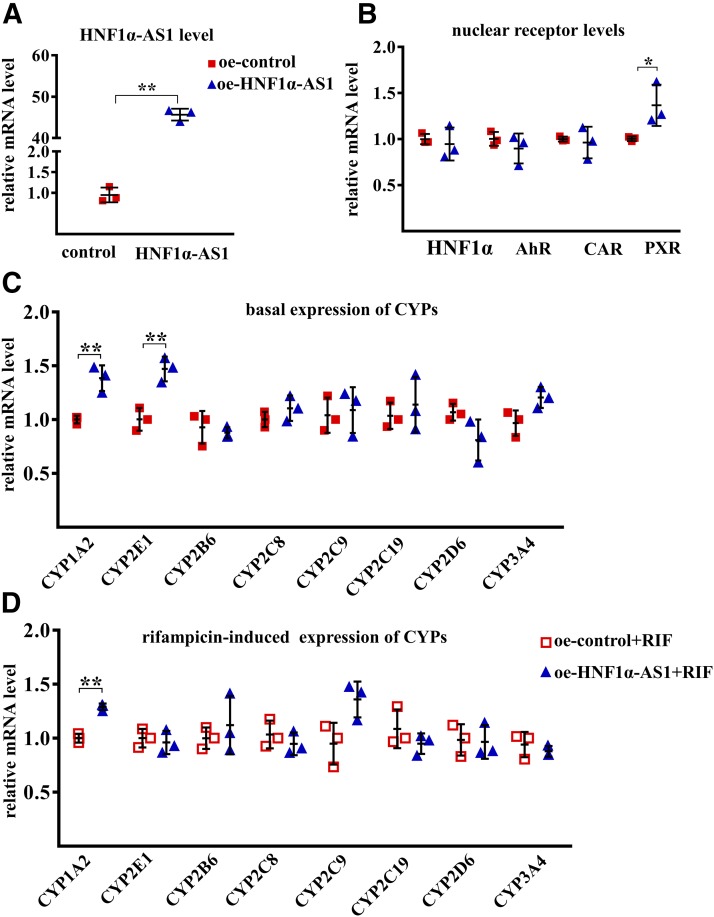

Overexpression of HNF1α-AS1 by transfection with an HNF1α-AS1 plasmid in Huh7 cells showed a 30-fold increase in HNF1α-AS1 in comparison with that from a control plasmid (Fig. 7A). An increase in PXR mRNA without an effect on the expression of AHR and CAR mRNA was observed (Fig. 7B). However, the basal expression levels of most P450 mRNAs remained unchanged except for CYP1A2 and 2E1 (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, no effect of HNF1α-AS1 overexpression was observed on rifampicin-induced expression of P450s except for an increase in CYP1A2 induction (Fig. 7D). These results suggested that endogenous expression of HNF1α-AS1 is needed in the regulation of PXR as well as most P450s, and the regulation of the transcription of P450s by HNF1α may be mediated by alteration of both HNF1α-AS1 and transcriptional regulators.

Fig. 7.

Effects of HNF1α-AS1 overexpression on mRNA levels of the studies genes. (A) Expression levels of HNF1α-AS1 in control and HNF1α-AS1-overexpressing (oe) Huh7 cells. (B) Impact of HNF1α-AS1 overexpression on the expression of HNF1A, AHR, CAR, and PXR mRNAs. (C) Impact of HNF1α-AS1 overexpression on the basal expression of P450 mRNAs. (D) Impact of HNF1α-AS1 overexpression on the rifampicin-induced expression of P450 mRNAs. Data points from three independent experiments are shown as dots along with the mean ± S.D., *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 in comparison of HNF1α-AS1 overexpression with the control group by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

Discussion

Expression of P450s in liver cells is largely regulated at transcriptional levels by nuclear receptors. HNF1α and HNF4α are two key transcription factors in the regulation of basal expression of P450s (Liu and Gonzalez, 1995; Jover et al., 2001; Cheung et al., 2003; Kamiyama et al., 2007), whereas PXR and CAR are two key transcription factors in the control of drug-induced expression of P450s (Goodwin et al., 1999; Waxman, 1999; Tompkins and Wallace, 2007). PXR and CAR often require crosstalk with HNF1α and HNF4α as coactivators (Tirona et al., 2003; Li and Chiang, 2006). HNF1α is a liver-enriched transcription factor, the overexpression of which in HepG2 cells enhances the expression of CYP3A4, 1A1, and 2C9 (Chiang et al., 2014). In the current study, strong correlations between the mRNA level of HNF1α and transcriptional regulators PXR, CAR, and AhR, as well as several P450s in human liver tissues, were observed (Supplemental Table S2). Loss- and gain-of-function studies showed that alteration of the HNF1α expression directly resulted in changes to the mRNA levels of PXR, CAR, and AhR (Fig. 4C; Fig. 5C). The regulatory mechanisms may be associated with direct binding of HNF1α on the target promoters, as it has been reported that an HNF1α-binding site is located in the PXR promoter (Uno et al., 2003; Aouabdi et al., 2006). More importantly, the expression of HNF1α also showed obvious impact on the basal and rifampicin-induced expression of several P450s (Fig. 4, D and E; Fig. 5, D and E). These results were in accordance with our recently published study in HepaRG cells (Chen et al., 2018).Together with previous studies, the current findings support HNF1α as a key regulator of both the transcriptional regulators and P450s.

However, the regulatory mechanisms behind the impact of HNF1α on the expression of transcriptional regulators and P450s are far from being well understood. In this study, the role of lncRNA HNF1α-AS1 in the HNF1α-mediated regulation of P450 expression in liver cells was determined. LncRNAs have attracted much more attentions owing to their irreplaceable functions in the regulation of many physiologic processes (Khorkova et al., 2015). LncRNAs can interact with a wide range of biologic molecules to regulate gene expression, such as proteins, DNAs, and RNAs (Villegas and Zaphiropoulos, 2015). In particular, a large group of proteins that interact with lncRNAs are transcriptional factors. For example, the lncRNA long-intergenic noncoding Linc-YY1, derived from the promoter of transcriptional factor YY1, interacts with YY1 to remove the YY1/polycomb repressive complex from target promoters, which leads to activation of downstream genes and promotes muscle regeneration (Zhou et al., 2015). Interactions of transcription factors with their genomic neighboring lncRNAs, particularly for sense-antisense pairs, have been considered as a general biologic phenomenon (Kung et al., 2013; Herriges et al., 2014). Transcriptional factor-derived lncRNAs often participate in the regulatory activities of their paired transcriptional factors (Zhou et al., 2015). Therefore, it is logical to speculate that the HNF1α-mediated transcription regulation of P450s and transcriptional regulators may require involvement of its neighboring antisense lncRNAs.

The involvement of lncRNA HNF1α-AS1 in HNF1α regulatory function was first determined in an initial study wherein we screened differently expressed lncRNAs associated with differential expression of CYP3A4. Differentially expressed lncRNAs determined via microarray analysis identified a set of candidate lncRNAs (Fig. 1C), which included lncRNA HNF1α-AS1 in a list of the top associated lncRNAs (Fig. 1D). The HNF1α-AS1 gene is located next to the HNF1A gene on the antisense strand in chromosome 12 (Fig. 2A). Compared with the HNF1A DNA sequence, the HNF1α-AS1 sequence is much less frequently conserved outside of mammals (Fig. 2, B and C), implying a certain extent of involvement of HNF1α-AS1 in HNF1α regulatory function in the mammalian liver.

The involvement of HNF1α-AS1 in HNF1α regulatory function was further demonstrated in a correlation study with 43 human liver tissue samples (Fig. 3). Expression of HNF1α-AS1 was found to be statistically significantly correlated with the mRNA expression levels of most selected P450s as well as that of HNF1α, CAR, and PXR in the human liver tissues (Fig. 3, P < 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001 in Pearson correlation analysis).

The involvement of HNF1α-AS1 in HNF1α regulatory function on P450 expression is supported by loss- or gain-of-function studies in human Huh7 cells. Alterations of HNF1α-AS1 expression by either siRNA knockdown or plasmid overexpression directly resulted in significant changes to the mRNA levels of numerous P450s tested as well as transcriptional regulators (Figs. 6 and 7) without a concomitant change of HNF1α, suggesting that a network composed of HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1 is the upstream regulator of nuclear receptors, which then further mediate the basal and drug-induced P450 expression. Knockdown of the endogenous expression of HNF1α-AS1 showed similar effects on the basal expression of P450s compared with that obtained from silencing the expression of HNF1α (Fig. 4D; Fig. 6C). However, among the three transcriptional regulators, only PXR mRNA was affected by knockdown of HNF1α-AS1 (Fig. 6B).We found that knockdown of HNF1α-AS1 in Huh7 cells did not affect the AhR mRNA level but significantly increased the CYP1A2 mRNA level, inconsistently with the result in liver tissue in Supplemental Fig. 2. Functional experiments may not be sufficient to detect CAR and AhR effects, because the basal expression level of CAR and AhR is lower in huh7 cells (data not shown). There may be other differences in expression of transcription factors between different cell types. We have previously reported that lncRNA transcription factors and receptors form a complex regulatory network that regulates P450 enzyme expression (Chen et al., 2018). Therefore, we speculate that the regulation of CYP1A2 is a complex process that requires additional in-depth study. In addition, the impact of HNF1α-AS1 knockdown on rifampicin-induced expression of P450s was also not identical to that obtained with HNF1α knockdown. Specifically, the impact on the induction of CYP1A2, 2C8, and 2C19 by HNF1α-AS1 knockdown was different compared with that from knockdown of HNF1α (Fig. 4E; Fig. 6D). Moreover, exogenous expression of HNF1α-AS1 also showed different effects on the basal and rifampicin-induced expression of P450s compared with that consequent to HNF1α overexpression (Fig. 5, D and E; Fig. 7, C and D), although the same effect on the transcription of PXR was observed (Fig. 7B). We have not yet found a reasonable explanation for these data and will continue to determine the underlying mechanisms for the induction of CYP1A2 in the HNF1α-AS1 overexpression experiment. However, it could be concluded that the HNF1α and HNF1α-AS1 pair is involved in PXR-mediated basal expression of P450 genes but may function in different ways with regard to their induced expression.

A detailed determination of the mechanisms by which HNF1α-AS1 is involved in the HNF1α-mediated regulatory function in liver cells will require further analyses. The physiologic functions of HNF1α-AS1 were first identified in the regulation of cell proliferation and migration in esophageal adenocarcinoma cells (Yang et al., 2014). The role of HNF1α-AS1 in the promotion of cancer progression and metastasis in gastrointestinal tract organs has been reported, including in pancreatic cancer (Muller et al., 2015), gastric cancer (Dang et al., 2015), and hepatocellular carcinoma (Liu et al., 2016). HNF1α-AS1 has been considered an oncogene (Liu et al., 2016) and may serve as a biomarker for cancer prognosis (Zhang et al., 2017). Mechanistically, HNF1α-AS1 may function as a competing endogenous RNA to repress miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation in cancer progression (Fang et al., 2017). Transcriptional regulation of HNF1α-AS1 by HNF1α has also been reported in hepatocellular carcinoma (Ding et al., 2018). HNF1α-AS1 was further shown to directly bind to the C terminus of Scr homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 and increase the phosphatase activity of this protein, which can reverse the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma (Ding et al., 2018).

Given that we have found that HNF1α and lncRNA HNF1α-AS1 constitute a regulatory network involved in receptor-mediated regulation of P450 enzyme expression, it therefore appears, based on current reports, that HNF1α-AS1 acts at the core of this regulatory mechanism. Moreover, such studies have provided potential future directions to further illustrate the molecular mechanisms of HNF1α-AS1 in the involvement of the HNF1α-mediated regulatory function in liver cells. A clear understanding of these mechanisms from the perspective of regulatory networks is necessary to support the clinical application of epigenetic regulation of drug metabolism and to facilitate the discovery of novel targets and strategies for the development of new drugs. For example, future research may reveal that lncRNAs regulate the expression of P450s by acting as a bridge, although the detailed mechanisms have not been established and should be explored further.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that lncRNA HNF1α-AS1, an antisense RNA of HNF1α, is involved in the HNF1α-mediated regulation of the expression of P450s and nuclear receptors in human liver cells.

Abbreviations

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HNF1α

hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha

- HNF1α-AS1

hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha antisense 1

- HNF4α

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha

- HNF4α-AS1

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha antisense 1

- lncRNA

long noncoding RNA

- miRNA

microRNA

- P450s

cytochrome P450s

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Yan, Zhong, Han, Zhang.

Conducted experiments: Y. Wang, Yan, J. Liu, S. Chen, G. Liu, Nie, P. Wang, Yang.

Performed data analysis: Y. Wang, Yan, L. Chen, Zhong, Zhang.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Yan, Zhong, Zhang.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant 81773815 and U1604163 (L.Z.)] and the US National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R01GM-118367 (X.Z)].

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Aouabdi S, Gibson G, Plant N. (2006) Transcriptional regulation of the PXR gene: identification and characterization of a functional peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha binding site within the proximal promoter of PXR. Drug Metab Dispos 34:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Bao Y, Piekos SC, Zhu K, Zhang L, Zhong XB. (2018) A transcriptional regulatory network containing nuclear receptors and long noncoding RNAs controls basal and drug-induced expression of cytochrome P450s in HepaRG cells. Mol Pharmacol 94:749–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C, Akiyama TE, Kudo G, Gonzalez FJ. (2003) Hepatic expression of cytochrome P450s in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-alpha (HNF1alpha)-deficient mice. Biochem Pharmacol 66:2011–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang TS, Yang KC, Chiou LL, Huang GT, Lee HS. (2014) Enhancement of CYP3A4 activity in Hep G2 cells by lentiviral transfection of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha. PLoS One 9:e94885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y, Lan F, Ouyang X, Wang K, Lin Y, Yu Y, Wang L, Wang Y, Huang Q. (2015) Expression and clinical significance of long non-coding RNA HNF1A-AS1 in human gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol 13:302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding CH, Yin C, Chen SJ, Wen LZ, Ding K, Lei SJ, Liu JP, Wang J, Chen KX, Jiang HL, et al. (2018) The HNF1α-regulated lncRNA HNF1A-AS1 reverses the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma by enhancing the phosphatase activity of SHP-1. Mol Cancer 17:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C, Qiu S, Sun F, Li W, Wang Z, Yue B, Wu X, Yan D. (2017) Long non-coding RNA HNF1A-AS1 mediated repression of miR-34a/SIRT1/p53 feedback loop promotes the metastatic progression of colon cancer by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cancer Lett 410:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin B, Hodgson E, Liddle C. (1999) The orphan human pregnane X receptor mediates the transcriptional activation of CYP3A4 by rifampicin through a distal enhancer module. Mol Pharmacol 56:1329–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTEx Consortium (2013) The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 45:580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Nie YL, Li JF, Meng XG, Yang WH, Chen YL, Wang SJ, Ma X, Kan QC, Zhang LR. (2016) Developmental regulation of CYP3A4 and CYP3A7 in Chinese Han population. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 31:433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herriges MJ, Swarr DT, Morley MP, Rathi KS, Peng T, Stewart KM, Morrisey EE. (2014) Long noncoding RNAs are spatially correlated with transcription factors and regulate lung development. Genes Dev 28:1363–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelman-Sundberg M, Sim SC, Gomez A, Rodriguez-Antona C. (2007) Influence of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on drug therapies: pharmacogenetic, pharmacoepigenetic and clinical aspects. Pharmacol Ther 116:496–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jover R, Bort R, Gómez-Lechón MJ, Castell JV. (2001) Cytochrome P450 regulation by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 in human hepatocytes: a study using adenovirus-mediated antisense targeting. Hepatology 33:668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama Y, Matsubara T, Yoshinari K, Nagata K, Kamimura H, Yamazoe Y. (2007) Role of human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in human hepatocytes assessed by use of small interfering RNA. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 22:287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Bonasio R, Saldaña-Meyer R, Yoshida T, Son J, Nishino K, Umezawa A, Reinberg D. (2014) Interactions between JARID2 and noncoding RNAs regulate PRC2 recruitment to chromatin. Mol Cell 53:290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorkova O, Hsiao J, Wahlestedt C. (2015) Basic biology and therapeutic implications of lncRNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 87:15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung JT, Colognori D, Lee JT. (2013) Long noncoding RNAs: past, present, and future. Genetics 193:651–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Chiang JY. (2006) Rifampicin induction of CYP3A4 requires pregnane X receptor cross talk with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha and coactivators, and suppression of small heterodimer partner gene expression. Drug Metab Dispos 34:756–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SY, Gonzalez FJ. (1995) Role of the liver-enriched transcription factor HNF-1 alpha in expression of the CYP2E1 gene. DNA Cell Biol 14:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Wei X, Zhang A, Li C, Bai J, Dong J. (2016) Long non-coding RNA HNF1A-AS1 functioned as an oncogene and autophagy promoter in hepatocellular carcinoma through sponging hsa-miR-30b-5p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 473:1268–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Bajic VB, Zhang Z. (2013) On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol 10:925–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller S, Raulefs S, Bruns P, Afonso-Grunz F, Plötner A, Thermann R, Jäger C, Schlitter AM, Kong B, Regel I, et al. (2015) Next-generation sequencing reveals novel differentially regulated mRNAs, lncRNAs, miRNAs, sdRNAs and a piRNA in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer 14:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair PC, McKinnon RA, Miners JO. (2016) Cytochrome P450 structure-function: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Drug Metab Rev 48:434–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie YL, He H, Li JF, Meng XG, Yan L, Wang P, Wang SJ, Bi HZ, Zhang LR, Kan QC. (2017) Hepatic expression of transcription factors affecting developmental regulation of UGT1A1 in the Han Chinese population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 73:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YZ, Gao W, Yu AM. (2009) MicroRNAs regulate CYP3A4 expression via direct and indirect targeting. Drug Metab Dispos 37:2112–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Zhong X. (2015) Epigenetic regulation of drug metabolism and transport. Acta Pharm Sin B 5:106–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto N, Dolan ME. (2011) Clinically relevant genetic variations in drug metabolizing enzymes. Curr Drug Metab 12:487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Chen S. (2015) Epigenetic regulation of cytochrome P450 enzymes and clinical implication. Curr Drug Metab 16:86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirona RG, Lee W, Leake BF, Lan LB, Cline CB, Lamba V, Parviz F, Duncan SA, Inoue Y, Gonzalez FJ, et al. (2003) The orphan nuclear receptor HNF4alpha determines PXR- and CAR-mediated xenobiotic induction of CYP3A4. Nat Med 9:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins LM, Wallace AD. (2007) Mechanisms of cytochrome P450 induction. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 21:176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy TS, Chaudhry AS, Prasad B, Thummel KE, Schuetz EG, Zhong XB, Tien YC, Jeong H, Pan X, Shireman LM, et al. (2016) Interindividual variability in cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 44:343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y, Nakajima M, Takagi S, Taniya T, Yokoi T. (2006) MicroRNA regulates the expression of human cytochrome P450 1B1. Cancer Res 66:9090–9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno Y, Sakamoto Y, Yoshida K, Hasegawa T, Hasegawa Y, Koshino T, Inoue I. (2003) Characterization of six base pair deletion in the putative HNF1-binding site of human PXR promoter. J Hum Genet 48:594–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas VE, Zaphiropoulos PG. (2015) Neighboring gene regulation by antisense long non-coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci 16:3251–3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, Sanyal A, Corces-Zimmerman R, Chen Y, Lajoie BR, Protacio A, Flynn RA, Gupta RA, et al. (2011) A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature 472:120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman DJ. (1999) P450 gene induction by structurally diverse xenochemicals: central role of nuclear receptors CAR, PXR, and PPAR. Arch Biochem Biophys 369:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Wang Y, Liu J, Nie Y, Zhong XB, Kan Q, Zhang L. (2017) Alterations of histone modifications contribute to pregnane X receptor-mediated induction of CYP3A4 by rifampicin. Mol Pharmacol 92:113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Song JH, Cheng Y, Wu W, Bhagat T, Yu Y, Abraham JM, Ibrahim S, Ravich W, Roland BC, et al. (2014) Long non-coding RNA HNF1A-AS1 regulates proliferation and migration in oesophageal adenocarcinoma cells. Gut 63:881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AM, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Cherrington NJ, Aleksunes LM, Zanger UM, Xie W, Jeong H, Morgan ET, Turnbaugh PJ, Klaassen CD, et al. (2017) Regulation of drug metabolism and toxicity by multiple factors of genetics, epigenetics, lncRNAs, gut microbiota, and diseases: a meeting report of the 21st International Symposium on Microsomes and Drug Oxidations (MDO). Acta Pharm Sin B 7:241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AM, Tian Y, Tu MJ, Ho PY, Jilek JL. (2016) MicroRNA pharmacoepigenetics: posttranscriptional regulation mechanisms behind variable drug disposition and strategy to develop more effective therapy. Drug Metab Dispos 44:308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanger UM, Klein K, Thomas M, Rieger JK, Tremmel R, Kandel BA, Klein M, Magdy T. (2014) Genetics, epigenetics, and regulation of drug-metabolizing cytochrome p450 enzymes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 95:258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanger UM, Schwab M. (2013) Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther 138:103–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Xiong Y, Tang F, Bian Y, Chen Y, Zhang F. (2017) Long noncoding RNA HNF1A-AS1 indicates a poor prognosis of colorectal cancer and promotes carcinogenesis via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 96:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Sun K, Zhao Y, Zhang S, Wang X, Li Y, Lu L, Chen X, Chen F, Bao X, et al. (2015) Linc-YY1 promotes myogenic differentiation and muscle regeneration through an interaction with the transcription factor YY1. Nat Commun 6:10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SF, Liu JP, Chowbay B. (2009) Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact. Drug Metab Rev 41:89–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]