Abstract

Ventricular Arrhythmias (VAs) may present with a wide spectrum of clinical manifesta-tions ranging from mildly symptomatic frequent premature ventricular contractions to life-threatening events such as sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death. Myocardial scar plays a central role in the genesis and maintenance of re-entrant arrhythmias which are commonly associated with Structural Heart Diseases (SHD) such as ischemic heart disease, healed myocarditis and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. However, the arrhythmogenic substrate may remain unclear in up to 50% of the cases after a routine diagnostic workup, comprehensive of 12-lead surface ECG, transthoracic echocardiography and coronary angiography/computed tomography. Whenever any abnormality cannot be identified, VAs are referred as to “idiopathic”. In the last dec-ade, Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) imaging has acquired a growing role in the identification and characterization of myocardial arrhythmogenic substrate, not only being able to accurately and re-producibly quantify biventricular function, but, more importantly, providing information about the presence of myocardial structural abnormalities such as myocardial fatty replacement, myocardial oe-dema, and necrosis/ fibrosis, which may otherwise remain unrecognized. Moreover, CMR has recent-ly demonstrated to be of great value in guiding interventional treatments, such as radiofrequency abla-tion, by reliably identifying VA sites of origin and improving long-term outcomes. In the present manuscript, we review the available data regarding the utility of CMR in the workup of apparently “idiopathic” VAs with a special focus on its prognostic relevance and its application in planning and guiding interventional treatments.

Keywords: Cardiac magnetic resonance, idiopathic, late gadolinium enhancement, structural heart disease, tissue characterization, ventricular arrhythmias

1. INTRODUCTION

Ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) are frequently associated with Structural Heart Diseases (SHD) such as healed myocardial infarction, chronic myocarditis and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. Traditionally, in the absence of cardiac abnormalities on routine ECG or trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE), VAs are defined as “idiopathic”. The distinction between truly idiopathic VAs and those related to myocardial structural abnormalities is essential, as the latter are associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) [1]. Patients with apparently idiopathic VAs are usually screened for the presence of heart disease with a 12-lead surface electrocardiogram (ECG), TTE and exercise stress test. In selected, high-risk patients, non-invasive (i.e. computed tomography of the coronary arteries) or invasive (i.e. coronary angiography) imaging techniques are used to rule out the presence of significant coronary artery disease. However, subtle structural abnormalities may occasionally remain concealed to routine diagnostic workup. In this setting, Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) imaging may be of great value, being able to accurately define biventricular function and to characterize myocardial tissue by detecting focal fatty infiltration, tissue oedema related to inflammatory processes and areas of necrosis/fibrosis that could be related to early stage cardiomyopathies and could otherwise remain unrecognized [2]. Beyond diagnosis and risk stratification, in the last few years, CMR has also progressively established its role in guiding interventional treatments such as catheter ablation (CA) procedures [3]. In the present manuscript, we review the potential applications of CMR in the evaluation and management of patients with apparently idiopathic VAs and the evidence supporting them.

2. GENERAL CONCEPTS

Ventricular arrhythmias in patients with structurally normal heart are referred to as “idiopathic” VAs. Frequent Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs) account for approximately 90% of all idiopathic VAs, while sustained Ventricular Tachycardia (VT) and Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) are far less common [4]. Idiopathic VAs usually originate from the Right/Left Ventricular Outflow Tract (R/LVOT), His-Purkinje system, papillary muscles, right moderator band and epicardial foci, are commonly linked to triggered cAMP-mediated afterdepolarizations or automaticity and typically share a favourable prognosis [5, 6]. Conversely, VAs in the context of SHD are usually determined by scar-related reentry and are associated with increased mortality. The presence of surviving myocardial fibres within fibrous tissue leads to the formation of slow conduction pathways as well as to a dispersion of activation and refractoriness that constitute the milieu for reentrant circuits (Fig. 1) [7]. The identification of this arrhythmogenic substrate by CMR tissue characterization techniques is of great value in stratifying the risk of developing malignant VAs as well as in guiding therapeutic strategies [8].

Fig. (1).

Schematic representation of a reentry circuit as originally described by Stevenson et al. in 1993. In this “figure of eight” model, two activation wavefronts propagate around two lines of conduction block sharing a common pathway (central isthmus). Areas of dense scar (blue) cannot be excitable during tachycardia. Bystander pathways can be attached to any point in the circuit and represent areas of tissue activated by the wavefront but not playing an active role in the reentrant circuit.

In the specific setting of frequent PVCs (≥1000 on 24h Holter monitoring), their association with increased mortality among patients with SHD is well established [9, 10]. In contrast, the data linking frequent PVCs in patients with normal hearts to an increased risk of heart failure and cardiovascular mortality are discordant [11-14]. In a study of 73 asymptomatic subjects with an incidental finding of frequent PVCs and structurally normal heart, a single case of SCD occurred during 6.5-years follow-up [13]. Similarly, in another study including 61 subjects with isolated PVCs of right ventricular origin, no SCD events or progression to overt forms of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) was observed during a median follow-up of 15-years [14]. Conversely, in a large study of 1731 healthy individuals, the presence of frequent PVCs was correlated with a 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular mortality with a trend towards an even higher risk in patients with polymorphic PVC [15]. This trend has subsequently been confirmed by a series analyzing 222 patients with frequent PVCs and normal heart in which patients with polymorphic PVCs showed a 4-fold higher risk of Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) compared to patients with monomorphic PVCs [16]. In another large cohort of 11158 patients with structurally normal heart followed for a mean of 12-years, the occurrence of frequent PVCs was associated with a 4-fold increase risk of SCD among male subjects while no significant increase was documented among females [17]. Recently, an observational study involving more than 1000 healthy subjects, correlated the presence of PVCs with an increased risk of death and heart failure proportional to the arrhythmic burden. Specifically, subjects with a PVC burden in the third tertile of the distribution (>0.1% of ectopic beats during 24 hours), showed 48% increase in the relative risk of developing systolic dysfunction and 31% increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death during a median follow-up of 13-years [11]. Finally, a metanalysis of 11 studies involving a total of 106195 subjects found a 3-fold increased risk of SCD among subjects with frequent PVCs [12].

Unfortunately, none of the above investigations can definitely prove a direct relationship between frequent PVCs and increased cardiovascular risk due to the intrinsic selection bias of population-based studies. Indeed, even if high-risk patients like those with a known history of heart disease were excluded, the subjects were not systematically screened for SHD, making it impossible to distinguish between patients with truly idiopathic PVCs and those with PVCs being the epiphenomenon of an underlying cardiomyopathy. In most of the cases, the presence of heart disease was ruled out on the basis of medical history and physical examination; a more accurate screening, usually limited to ECG and TTE, was more rarely performed [2, 18-20]. These initial studies represented the background of further investigations applying advanced imaging techniques to clarify the real prevalence and prognostic implication of concealed structural abnormalities in patients with apparently idiopathic VAs. In particular, CMR tissue characterization techniques have demonstrated a high sensitivity in identifying concealed myocardial abnormalities missed by routine diagnostic workup [2, 21].

3. MAGNETIC RESONANCE TISSUE CHARACTERIZATION TECHNIQUES

3.1. Myocardial Fat Imaging

Presence of intramyocardial fat can be seen in healthy adults and in different pathologic conditions, including healed myocardial infarction, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy and, more rarely, idiopathic and post-myocarditic dilated cardiomyopathy [22-24]. CMR imaging permits the detection of intramyocardial fat using different methods [25]. The combination of a Fast or Turbo Spin Echo (FSE or TSE) pulse sequence with a chemically selective fat suppression pulse, the “Fat-Sat” pulse, or with a Short Time-of-inversion triple-Inversion Recovery (STIR) pulse, has been historically considered the gold standard for the clinical diagnosis of intramyocardial fat by CMR. Using this approach, intramyocardial fat in the conventional FSE images appears as a hyperintense myocardial region, while it appears hypointense in the Fat Sat FSE or STIR images. More recently, steady-state free precession (SSFP) imaging, which is the most used cine pulse sequence, has been demonstrated to detect the presence of intramyocardial fat with high accuracy, as well [25]. Tissue contrast in SSFP imaging relies on the ratio of T2/ T1. Therefore, the myocardium presents intermediate signal intensity, while fat and free water (blood pool) have high signal intensity. In SSFP images, when the interface fat–water is included in the same voxel for partial volume effect, the resulting signal is nulled producing the so-called “Indian Ink” artifact (which is a low-signal band surrounding high-signal central component).

3.2. Myocardial Oedema Imaging

Acute myocardial injuries, such as acute myocardial infarction and myocarditis, are commonly characterized by increased myocardial free water content due to intracellular (cytogenic) and extracellular, interstitial (vasogenic) myocardial oedema. T2-weighted CMR imaging permits the non-invasive detection of myocardial oedema in vivo. Standard T2-weighted imaging of myocardial oedema typically involves STIR FSE pulse sequences. The inversion pulses for fat and blood suppression, which determine dual suppression of fat and flowing blood signal, and the inverse T1 weighting properties of these sequences, which increase their sensitivity to free tissue water, provide excellent contrast between the oedematous (hyperintense) myocardium and the normal myocardium [26]. The STIR technique has some intrinsic limitations (e.g. low signal-to-noise ratio, signal loss due to through-plane cardiac motion, slow flow artifacts adjacent to the endocardium and artifacts related to fast heart rate) that may lead to false-positive or false-negative diagnosis; direct assessment of myocardial T2 value by using parametric mapping imaging techniques may overcome such limitations [26].

3.3. Late Gadolinium Enhancement Imaging

The development in the early 1980s and the refinement in the late 1990s of the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) technique, which permits to distinguish between scarred/fibrotic myocardium and normal myocardium, represented an important breakthrough in CMR imaging [27, 28]. The LGE technique relies on peculiar features of gadolinium chelated contrast agents (mainly gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid -Gd-DTPA-). After bolus injection, Gd-DTPA transfers from the intravascular to the extravascular, extracellular space (wash-in); wash-out later occurs with renal clearance. The normal myocardium is characterized by fast wash-in/wash-out contrast agent kinetics. Cardiac diseases causing an increase in the extravascular, extracellular space (i.e. ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathies, through interstitial expansion) or determining myocyte cell membrane rupture (i.e. acute myocardial infarction) promote increased distribution volume of Gd-DTPA and its accumulation in scarred/fibrotic myocardium; poor venous drainage may promote further accumulation of contrast and delay its wash-out. These differences in Gd-DTPA distribution volumes are better appreciated 10 minutes after contrast injection, when equilibrium concentrations in the blood and myocardium have been reached and result in differences in relaxivity rate R1 between normal and scarred/fibrotic myocardium, due to the T1 shortening caused by the contrast agent, which translate into specific differences in signal intensity using T1-weighted imaging techniques [29]. The sequences commonly used for LGE imaging are T1-weighted and rely on the use of a nonselective 180-degree IR preparation pulse followed by a delay (or inversion time [TI]) that allows the magnetization of normal myocardium to reach the zero crossing; at this time point, the differences in signal intensity between normal and scarred/fibrotic myocardium are maximized, because the contribution of normal myocardium to the MR signal is zero or nulled and appears dark, while the pathologic myocardium has a positive magnetization and appears bright or hyper-enhanced. Image acquisition is commonly performed 10-20 minutes after injection of Gd-DTPA at the dose of 0.1-0.2 mmol/kg using a TI between 250 and 350 ms and a Gradient Recalled Echo (GRE) readout, due to its ability to provide images with better contrast-to-noise and contrast-enhancement ratio, and with high spatial resolution [29]. While LGE imaging is not able to distinguish acute (necrosis) from chronic (scar) myocardial infarction, because both are characterized by an increase of the extracellular space, thereby requiring information derived by adjunctive MR imaging techniques which depict the acutely injured myocardium (such as T2-weighted imaging) for the differential diagnosis, it permits the distinction of myocardial necrosis/scarring of ischemic from non-ischemic origin. Enhancement with non-ischemic pattern does not relate to any epicardial coronary artery distribution area and may be midmyocardial, subepicardial, or diffuse subendocardial (Fig. 2) [20, 29, 30].

Fig. (2).

Ischemic and nonischemic patterns of late Gadolinium enhancement. (a) Ischemic enhancement is subendocardial to transmural in a vascular distribution; (b) Nonischemic enhancement may be midmyocardial, subepicardial, or diffuse subendocardial. Midmyocardial enhancement may be linear, patchy, or at the RV insertion points of the interventricular septum. DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy, HE = hyperenhancement. Reprinted with permission from Rajiah et al. [30].

4. PREVALENCE AND CHARACTERIZATION OF MYOCARDIAL STRUCTURAL ABNORMALITIES IN PATIENTS WITH IDIOPATHIC VAS

In the last decade, the widespread use of CMR imaging has represented a major turning point in the physio-pathologic understanding of idiopathic VAs leading to a downgrading of their real incidence. When assessed by CMR imaging, a non-negligible proportion of patients with apparently idiopathic VAs presents indeed focal myocardial abnormalities at the site of origin of VAs that may represent the result of local inflammatory processes (i.e. healed myocarditis or ischemia) or the early onset of a non-ischemic cardiomyopathic process [21, 31, 32].

Altogether, studies analyzing the role of CMR imaging among survivors of sudden cardiac arrest with an inconclusive diagnosis found CMR abnormalities in 358 out of 537 (67%) patients and LGE in 314 (58%) cases. Overall the use of CMR led to a new or alternate diagnosis in 151 out of 400 (38%) patients compared to routine diagnostic workup (Table 1) [33-38]. A large study including 157 patients presenting with sustained VT (88, 56%), non-sustained VT (52, 33%) or resuscitated VF (17, 11%) confirmed the incremental diagnostic role of CMR compared to a standard work-up based on ECG, TTE and coronary angiography especially in patients without prior history of SHD. The implementation of CMR determined a new diagnosis or a diagnostic change in 48 patients (31% of all and 43% of those without prior history of SHD). More importantly, evidence of SHD was found in 32 out of 84 (38%) of those with negative standard diagnostic work-up [39]. In line with these findings, concealed myocardial inflammation related to granulomatous disease (i.e. cardiac sarcoid and tuberculosis) has been detected by CMR and 18FDG-PET in 14 out of 22 (64%) patients presenting with sustained VT and no evidence of SHD on the basis of TTE [40]. Diagnostic refinement by CMR in patients presenting with sustained VAs/aborted SCD has important practical consequences both in terms of therapeutic approach to VAs and risk stratification. Current guidelines recommend family screening in cases of (aborted) SCD [41]. A retrospective study found that the addition of CMR to conventional diagnostic approach in 79 patients admitted for aborted SCD, sustained VT or unexplained syncope determined a diagnostic reclassification in 42 (53%) cases thus reducing the indication for family screening from 53 (67%) probands to 43 (54%) [42]. Recently, a CMR protocol comprehensive of T2-weighted (oedema imaging) and LGE (scar imaging) has been applied in 25 patients presenting with sustained VT, family history of SCD, normal biventricular function assessed by TTE and absence of coronary artery disease assessed by coronary angiography. Presence of LGE was found in 22 (88%) cases and abnormal T2 signal in 4 (16%) of them even if normal biventricular function was confirmed by CMR in all the patients [43]. In another study, a similar CMR protocol was applied to 110 patients presenting with frequent PVCs and normal heart by TTE [44]. Overall, no differences in T2 signal intensity were found in the patient group compared to 41 healthy controls while areas of LGE were found in 61 (55%) patients compared to only 8 (20%) controls; in all cases LGE showed a non-ischemic pattern with one or several foci more frequently located within the septum or the LV lateral wall [44]. Unfortunately, none of those studies provided information on the morphology of VAs on ECG or electrophysiological data confirmatory of a relationship between the abnormalities seen on CMR and the VA site of origin. In this regard, the prevalence of CMR abnormalities has been investigated among patients with apparently idiopathic VAs of RV origin with discordant findings [14, 45-53]. Some of the studies described the presence of focal CMR abnormalities like wall thinning, fatty infiltration and wall motion abnormalities, in up to 73% of the patients [14, 45-47]; whereas others showed only the presence of focal RV wall motion abnormalities without signal alterations [48, 49], or even absence of any CMR abnormality at all [50-52]. Some of these concepts were confirmed and extended by our group: we reported myocardial structural abnormalities in 23 out of 120 (19%) patients with apparently idiopathic VAs with a prevalence of only 4/74 (5%) among those with VAs of RV origin compared to 19/46 (41%) of those with VAs of LV origin [2, 18, 19]. Other than VA morphology, the presence of CMR abnormalities was associated with family history of SCD, presentation with sustained VT, male gender and age over 40-years (Figs. 3 and 4) [2]. These findings were subsequently confirmed in a series of 101 patients with frequent PVCs referred for CA. Pre-procedural CMR detected areas of LGE in 21 (21%) of the patients. At univariable analysis both PVCs of RBBB morphology (OR 10.04; p=0.002) and polymorphic PVCs (OR 4.25; p=0.03) were significantly associated with presence of LGE [54]. Presence of exercise-induced VAs has been recently pointed out as another clinical predictor of CMR myocardial abnormalities in a study involving 162 patients with exercise-induced PVCs but no history or evidence of SHD on routine diagnostic workup [55]. In this study elevated T2-weighted values consistent with myocardial oedema were found in 60 (37%) patients while LGE was present in 110 (68%) of the them, showing a subepicardial or mid-wall distribution mainly involving the septum (54% of the cases) and the lateral wall (36%), consistent with acute or previous myocarditis (Table 2) [55]. In our study CMR abnormalities included wall motion abnormalities (8% in the LV and 10% in the RV), intramyocardial fat signal (7% in the LV and 2% in the RV), focal myocardial oedema (a single case in the LV) and presence of LGE (18% in the LV and 1% in the RV) with a non-ischemic distribution pattern in all the cases. LGE areas were mainly localized within the inferior and inferior-lateral walls of the LV (46% of the cases) [2]. In a recent series of 321 patients with frequent PVCs who underwent CMR before a CA procedure, 64 (20%) had structural abnormalities, 94% of which having LGE [56]. The LGE pattern was consistent with previous myocardial infarction in 35% of the cases while a non-ischemic pattern was demonstrated in the remaining 65%. In 7 patients, structural abnormalities other than LGE were observed, including RV dysfunction in 3 patients, LV non-compaction in other 3 and a congenital LV aneurysm in 1. Consistently with previous reports, male gender, older age and baseline reduced LVEF were all correlated with the presence of SHD [56].

Table 1.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging findings among survivors of sudden cardiac arrest.

| Study | White et al. [ 33 ] | Neilan et al. [ 34 ] | Baritussio et al. [ 35 ] | Rodrigues et al. [ 36 ] | Zorzi et al. [ 37 ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of patients | 82 | 137 | 110 | 164 | 44 |

| CMR abnormalities, n (%) | 61 (74) | 104 (76) | 76 (69) | 80 (49) | 37 (84) |

| Wall motion abnormalities, n (%) | 61 (74) | NA | 55 (50) | 46 (28) | 22 (50) |

| Fat infiltration (T1-weighted imaging), n (%) | 3/42 (7) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Myocardial edema (T2-weighted imaging), n (%) | 14/82 (17) | NA | 18/58 (31) | 10/80 (13) | 18/44 (41) |

| Areas of LGE, n (%) | 46 (56) | 98 (71) | 72 (65) | 61 (37) | 37 (84) |

| LGE pattern, n (%) | Ischemic, 28 (34) Non-ischemic, 26 (32) Mixed, 9 (11) |

Ischemic, 66 (67) Non-ischemic, 32 (33) |

Ischemic, 42 (39) Non-ischemic, 26 (24) Mixed, 4 (3) |

Ischemic, 21 (13) Non-ischemic, 28 (17) Mixed, 5 (3) |

Ischemic, 20 (45) Non-ischemic, 17 (39) |

| New/alternate diagnosis compared to non-CMR imaging, n (%) | 41 (50) | NA | 45 (41) | 50 (30) | 15 (34) |

| Final diagnosis based on CMR findings, n (%) | Unexplained LV dysfunction, 5 (6) Ischemic heart disease, 29 (35) Myocarditis, 14 (17) Cardiac sarcoid, 3 (4) Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, 6 (7) Midwall fibrosis, 2 (2) Left ventricular non- compaction, 1 (1) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 1 (1) |

Ischemic heart disease, 60 (44) Myocarditis, 14 (10) Cardiac sarcoid, 3 (2) Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, 3 (2) Midwall fibrosis, 21 (15) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 3 (2) |

Non-specific findings, 9 (8) Ischemic heart disease, 45 (41) Non-ischemic heart disease not otherwise specified, 31 (28) |

Non-specific findings, 30 (18) Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, 27 (17) Myocarditis or cardiac sarcoid, 22 (13) Ischemic heart disease, 13 (8) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 9 (6) Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, 3 (2) Non-ischemic heart disease not otherwise specified, 2 (1) |

Ischemic heart disease, 20 (45) Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, 19 (43) Myocarditis, 4 (9) Mitral valve prolapse associated with LGE, 3 (7) Non-ischemic heart disease not otherwise specified, 2 (5) Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, 1 (2) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 1 (2) Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy, 1(2) |

Fig. (3).

Example of a 48-year old man without known cardiovascular risk factors and no previous history of heart disease presenting with sustained ventricular tachycardia of right bundle branch block morphology (A). His 12-Lead ECG obtained after electric cardioversion appeared to be normal (B). Cardiac magnetic resonance late gadolinium enhancement imaging demonstrated non-ischemic myocardial scar involving the basal inferolateral wall, with a subepicardial distribution (C - white arrow); reprinted with permission from Muser et al. [18].

Fig. (4).

Example of a 40-year-old man with family history of cardiomyopathy and apparently idiopathic frequent premature ventricular beats with RBBB morphology and superior QRS axis (A). Cardiac magnetic resonance T1-weighted imaging demonstrated signal abnormalities suggestive of myocardial fatty replacement of the lateral left ventricular wall (B). Late gadolinium enhancement with nonischemic pattern of the lateral left ventricular wall was also present (C-D); reprinted with permission from Nucifora et al. [2].

Table 2.

Clinical predictors and relative odds ratios of concealed myocardial structural abnormalities in patients with ventricular arrhythmias, normal biventricular function and no coronary artery disease.

| Predictor | OR |

|---|---|

| Family history of sudden cardiac death [2] | 5.0 |

| Male Gender [2] | 8.7 |

| Age ≥40 years [2] | 4.5 |

| Presentation with isolated premature ventricular contractions [44] | 2.8 |

| Presentation with sustained ventricular arrhythmias [2] | 7.9 |

| Exercise-Induced ventricular arrhythmias [55] | 7.9 |

| RBBB and superior QRS axis [2] | 21.2 |

5. PROGNOSTIC RELEVANCE OF CMR FINDINGS

The ability of CMR to identify patients at risk of malignant arrhythmic events in several overt heart diseases including ischemic LV dysfunction or Ischemic Heart Disease, nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and myocarditis has been convincingly proven [57]. Traditionally, LVEF played a significant role in defining the SCD risk in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, but in the last few years, a growing evidence highlighting the presence of LGE on CMR as an independent risk marker to LVEF has emerged. In a large study evaluating 373 patients presenting either with sustained VT (204, 55%) or non-sustained VT (169, 45%), the presence of LGE on CMR was the only independent predictor of the composite endpoint of SCD, sustained VT and appropriate Implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy at follow up (HR 3.26; p<0.001) regardless of baseline LVEF [58]. A very recent meta-analysis including 36 studies and 7882 patients has pointed out how LGE was strongly associated with all-cause mortality (HR 2.3), cardiovascular mortality (HR 3.3) and occurrence of VAs and SCD (HR 3.8) with an overall HR for MACE of 3.2 regardless of LVEF and aetiology [59]. The prognostic relevance of myocardial structural abnormalities detected in patients with apparently idiopathic VAs seems to move in the same direction with several reports showing an increased risk of major arrhythmic events in such patients compared to those without any CMR abnormalities [2, 34, 56, 60]. In the above-mentioned study from Neilan et al., the only independent predictors of the composite endpoint of all-cause death and appropriate ICD therapy during a median follow-up of 29 months among 137 survivors of sudden cardiac arrest were the presence of LGE (HR 6.7) and its extent (HR 1.2) [34]. In particular, an extent of LGE ≥8% was able to identify patients at risk of MACE with 90% sensitivity and 80% specificity [34]. In our previous report, we similarly found that the presence of myocardial structural abnormalities detected by CMR, together with the family history of SCD and clinical presentation with sustained VT, were significantly related to the occurrence of major arrhythmic events during a median follow-up of 14 months (Fig. 5) [2]. A recent study from the University of Padua, comparing 35 athletes presenting with complex VAs and evidence of subepicardial/mid-myocardial LGE to 38 athletes with VAs and no LGE and 40 healthy control athletes, found the presence of LGE being strongly associated with the risk of malignant arrhythmic events during follow-up: 4 athletes had appropriate ICD shocks, 1 had sustained VT and 1 had SCD during a mean follow-up of 38±25 months, and all of them had evidence of LGE. On the counterpart, no events at follow-up were observed in the group with VAs and no LGE and in the control group [60]. Comparable results have been found also in the specific setting of frequent PVCs. Aquaro et al. has reported a 32-fold increased risk of major arrhythmic events among patients with evidence of structural RV abnormalities on CMR in a cohort of 400 patients with RVOT PVCs [61], while a prospective study involving 239 patients with frequent RVOT/LVOT PVCs and normal CMR did not show any MACE during a median follow-up of 5.6 years further confirming the importance of abnormal CMR findings as predictor of risk [62]. In a recent series of 321 patients undergoing CA for frequent PVCs, the combination of pre-procedural CMR with programmed electrical stimulation (PES) has demonstrated to further improve patient risk stratification compared to CMR alone [56]. Specifically, the combination of SHD on CMR and VT inducibility on PES independently conferred a 26-fold increased risk of MACE during a median of 20-months follow-up regardless of baseline LVEF, while the presence of SHD alone was associated with only a 2-fold increased risk [56] (Fig. 6).

Fig. (5).

Example of a 24-years old men with frequent premature ventricular contractions and significant family history for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death (SCD) as demonstrated by his family pedigree (A, arrowhead: proband, red: subjects affected by cardiomyopathy, yellow: subjects who died from SCD, blue: subjects affected by breast cancer, males and females are represented by squares and circles, respectively, figures marked by slash: dead patients, number below squares and circles: age of the patients). Proband's 12-lead ECG showed PVC of right bundle branch block morphology and sinus beats within normality (B). Cardiomyopathy-related myocardial morphological changes are shown in histological sections of the explanted heart of the proband's father (C-E). A spectrum of changes is seen: focal degeneration and necrosis of cardiomyocytes with no or minimal cellular response, myocyte loss and replacement fibrosis. Low magnification shows intra-myocardial (C) and sub-epicardial (D) areas of dense fibrotic scar with a patchy distribution (blue with Mallory trichromic stain). Higher magnification reveals foci of myocardial degeneration with vacuolization of cardiomyocytes (E-F, arrows, Hematoxylin and Eosin stain). Necrotic cardiomyocytes exhibit homogeneously brightly eosinophilic sarcoplasm with pyknotic or karyorrhectic nuclei (panels E-F, arrows). Proband's LGE-CMR demonstrated diffuse myocardial scar with a non-ischemic pattern (sub-epicardial and intra-myocardial) involving the interventricular septum and LV lateral wall evident in both three-chamber (G, arrows) and short-axis cross sections (H, arrows). Reprinted with permission from Muser et al. [19].

Fig. (6).

Forest plot showing the results of principal studies investigating the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events associated with the presence of myocardial structural abnormalities detected by cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with apparently idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias.

6. FUTURE PERSPECTIVES: T1 Mapping & Diffusion tensor Imaging

The use of classic CMR tissue characterization techniques such as LGE imaging has been demonstrated to significantly improve the detection and characterization of the arrhythmogenic substrate in patients with apparently idiopathic VAs. However, LGE imaging is unable to identify abnormal electrophysiologic findings at the site of origin of VAs in about one third of the cases [63-65]. This phenomenon may be related to the presence of interstitial fibrosis, which is undetectable by LGE imaging. The LGE technique, that relies on the difference in signal intensity between pathologic and normal myocardium, is indeed useful to identify focal areas of myocardial necrosis or replacement fibrosis; conversely, it fails when dealing with diseases (particularly non-ischemic cardiomyopathies) leading to interstitial myocardial fibrosis only, as the amount of fibrotic tissue may not reach the critical amount needed to be detected by LGE imaging [66, 67]. Some emerging techniques like T1-mapping and diffusion tensor imaging may overcome this limitation and lead to a better characterization of the arrhythmic substrate [68].

The T1 mapping technique allows the measurement of native (i.e. pre-contrast) and post gadolinium-based contrast media injection myocardial T1 value, and enables the calculation of the myocardial extracellular volume fraction, which represents the amount of interstitial fibrosis [69]. Among the several MRI sequences proposed for T1 mapping, the Modified Look-Locker Inversion-recovery (MOLLI), is currently the most widely used; originally described by Messroghli et al. [70]. It consists of a single shot TrueFISP image with acquisitions over different inversion time readouts allowing for magnetization recovery of a few seconds after 3 to 5 readouts. After pre-contrast and post-contrast image acquisition, T1 parametric maps are generated, which are used for the measurement of myocardial T1 values; patients affected by cardiac diseases leading to increased extracellular space have longer native T1 values and shorter T1 values after gadolinium administration with delayed normalization with contrast wash-out. The few experiences reported so far on the potential application of T1-mapping in VT substrate characterization in patients without clear evidence of LGE have shown consistency between increased native T1 values, low-voltage areas on EAM and VT sites of origin (Fig. 7) [64, 71].

Fig. (7).

Example of a patient with frequent premature ventricular contractions and left ventricular non- compaction as seen with cardiac magnetic resonance (A - black arrows). Non- compacted walls do not show evidence of late gadolinium enhancement (B). Endocardial bipolar voltage map did not show any abnormality (C) while a region of low unipolar voltage was present on the inferior and lateral wall in a location consistent with the non-compacted segments (D). Native T1 mapping revealed increased T1 relaxation time (E – red colour indicated by arrows), and post contrast T1 mapping revealed decreased T1 relaxation time (F - white arrows) consistent with interstitial fibrosis. This matched the region of unipolar voltage abnormality (reprinted with permission from Muser et al. [64]).

Diffusion-weighted CMR imaging is a technique initially applied to neuroimaging to study the course and spatial orientation of white matter fibres by mapping the diffusion process of water molecules. Diffusion of water molecules within tissues does not happen freely but is influenced by many obstacles, such as macromolecules, fibres, and biological membranes. Therefore, water diffusion patterns can reveal details about tissue architecture. Diffusion tensor imaging can be applied to the heart to study the 3D architecture of myocardial fibres without the need for contrast agents [72]. Scarred areas of the myocardium may present a fibre disarray potentially detectable by CMR-tractography. Preliminary reports have shown good correlation between areas of altered propagation angle and low voltage on EAM [73]. In the future, this technique can possibly improve interventional treatments of VT by better characterizing the complex architectural interaction between normal myocardium and scar.

7. ROLE OF CMR IN INTERVENTIONAL STRATEGIES

Recent advances in the field of CMR imaging have made possible to characterize the arrhythmogenic substrate in patients with VT with a high degree of precision; this allowed expanding the role of CMR imaging from a predominantly diagnostic tool to a tool able to guide interventional procedures by integrating anatomic and functional substrate information and therefore improving procedural efficacy [3, 74]. Since the late 1990s, VT ablation procedures rely on Electroanatomical Mapping (EAM) systems which invasively provide an integration of electrogram recordings with anatomic location by creating a 3-dimensional voltage map of the ventricle [75]. The use of EAM alone has several limitations mostly related to catheter electrode-tissue contact inconsistencies, electrodes size and interelectrode distances that may limit the field of view and therefore underestimate or miss deep intramural or sub-epicardial substrates [76]. In this setting, integration of imaging data with EAM may allow a more accurate definition of the arrhythmogenic substrate, a precise characterization of the anatomy of cardiac chambers, the course of coronary vessels and phrenic nerve, and identifying the presence of endocardial thrombi that may obstacle the procedure [74]. Several studies have consistently proven the correlation between areas of scar detected by LGE imaging and EAM low-voltage areas both in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies [66, 77-81]. Moreover, CMR-derived substrate has shown to be able to reliably identify up to 90% of critical VT isthmuses and abnormal electrograms which represent a potential target for substrate-based ablation approaches [82]. In a recent study by Yamashita et al., image integration has shown to significantly impact the procedural strategy in up to 60% of VT CA cases by leading to additional mapping/ablation focused on scar areas, addressing towards the need for epicardial access and modifying the ablation approach accordingly to difficult anatomy [82-84]. Finally, even if it requires being proven by larger studies, there is initial evidence that image integration may also improve the long-term outcome by reducing VT recurrence rates after CA procedures [82, 85].

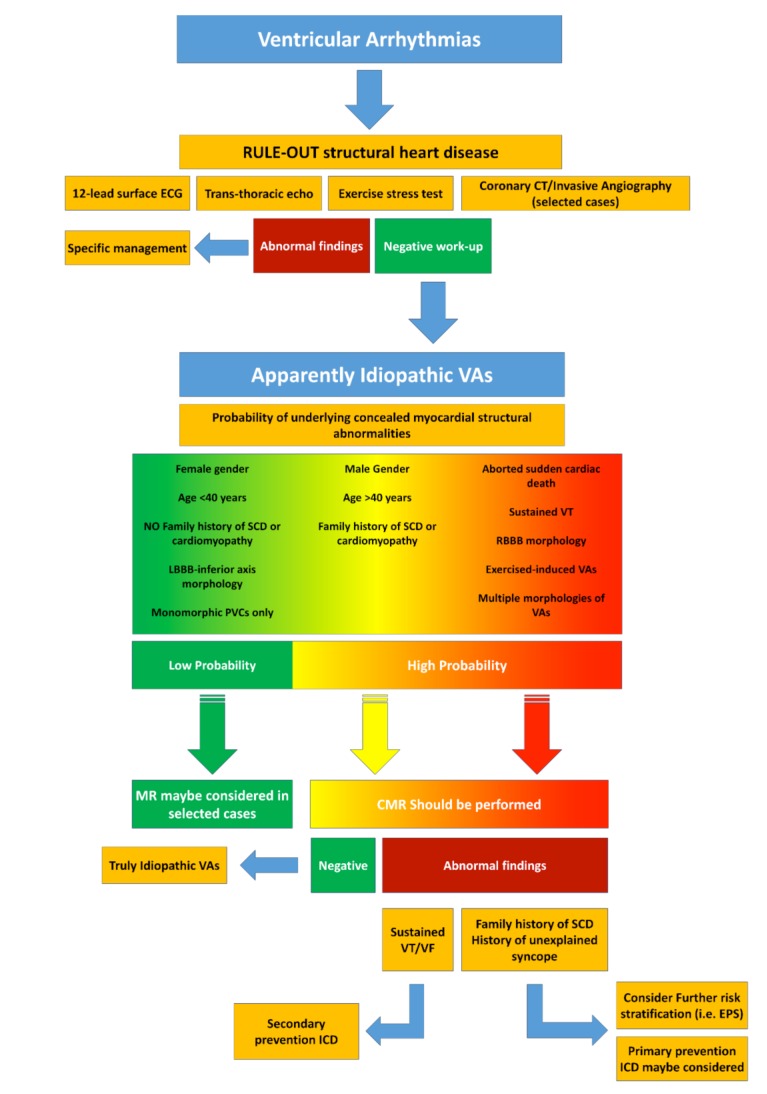

8. SUGGESTED APPROACH TO PATIENTS WITH APPARENTLY IDIOPATHIC VENTRICULAR ARRHYTHMIAS

The clinical approach to patients with apparently idiopathic VAs should aim to rule out the presence of underlying SHD and to define the consequent risk of SCD. In this regard, the routine diagnostic workup includes 12-lead surface ECG, TTE, 24-hours Holter monitoring and stress test (to rule out myocardial ischemia and determine the presence and burden of VAs during physical activity). In presence of abnormal baseline investigations or clinical features potentially linked to the presence of structural abnormalities (e.g. VAs with right bundle branch block morphology or polymorphic VAs, exercise-induced VAs, sustained VT or aborted sudden cardiac arrest at presentation, male gender, age > 40, family history of SCD), further CMR imaging should always be considered. When myocardial structural abnormalities are detected, further risk stratification may be necessary (i.e. by invasive electrophysiological study) while patients with documented sustained VT or aborted sudden cardiac arrest should always be protected from malignant arrhythmic events by ICD implantation, in accordance to current guidelines [41]. ICD implantation should be considered also for primary prevention in patients with high-risk features such as the history of unexplained syncope or the presence of a family history of SCD [86]. A close clinical follow-up should conversely be pursued in patients with evidence of CMR-abnormalities without other clinical high-risk features (Fig. 8).

Fig. (8).

Diagram representing the proposed algorithm for the diagnostic work-up and management of patients presenting with apparently idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. VAs: Ventricular Arrhythmias, VT: Ventricular Tachycardia; SCD: Sudden Cardiac Death; LBBB: Left bundle branch block; RBBB: Right Bundle Branch Block; PVCs: Premature Ventricular Contractions; CMR: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance; VF: Ventricular Fibrillation; ICD: Implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator; EPS: Electrophysiological Study.

CONCLUSION

CMR has a pivotal role in the management of patients with VAs of uncertain origin. Combination of CMR findings with clinical characteristics and electrophysiologic data may significantly improve risk stratification, accurately identifying those patients with high-risk characteristics that may benefit from ICD implantation. Moreover, CMR represents a valuable tool to guide interventional treatments, potentially improving long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Declared none.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- 1.Tan A.Y., Ellenbogen K. Ventricular arrhythmias in apparently normal hearts. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2016;8:613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nucifora G., Muser D., Masci P.G., et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of concealed structural abnormalities in patients with apparently idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias of left versus right ventricular origin A magnetic resonance imaging study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:456–462. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.001172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahida S., Sacher F., Dubois R., et al. Cardiac imaging in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2017;136:2491–2507. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latif S., Dixit S., Callans D.J. Ventricular arrhythmias in normal hearts. Cardiol. Clin. 2008;26:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saksena S., Camm A.J. Electrophysiological disorders of the heart: Expert consult. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerman B.B. Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment of outflow tract tachycardia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015;12:597–608. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson W.G., Khan H., Sager P., et al. Identification of reentry circuit sites during catheter mapping and radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia late after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993;88:1647–1670. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marchlinski F.E., Callans D.J., Gottlieb C.D., Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;101:1288–1296. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruberman W., Weinblatt E., Goldberg J.D., Frank C.W., Shapiro S. Ventricular premature beats and mortality after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1977;297:750–757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197710062971404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiang B.N., Perlman L.V., Ostrander L.D., Epstein F.H. Relationship of premature systoles to coronary heart disease and sudden death in the Tecumseh epidemiologic study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1969;70:1159–1166. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-70-6-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dukes J.W., Dewland T.A., Vittinghoff E., et al. Ventricular ectopy as a predictor of heart failure and death. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;66:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ataklte F., Erqou S., Laukkanen J., Kaptoge S. Meta-analysis of ventricular premature complexes and their relation to cardiac mortality in general populations. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013;112:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy H.L., Whitlock J.A., Sprague M.K., Kennedy L.J., Buckingham T.A., Goldberg R.J. Long-term follow-up of asymptomatic healthy subjects with frequent and complex ventricular ectopy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985;312:193–197. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501243120401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaita F., Giustetto C., Di Donna P., et al. Long-term follow-up of right ventricular monomorphic extrasystoles. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001;38:364–370. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel G., Cho S., Ghayoumi A., et al. Prognostic significance of PVCs and resting heart rate. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2007;12:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2007.00150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ephrem G., Levine M., Friedmann P., Schweitzer P. The prognostic significance of frequency and morphology of premature ventricular complexes during ambulatory holter monitoring: Prognostic significance of multiform PVCs. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2013;18:118–125. doi: 10.1111/anec.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirose H., Ishikawa S., Gotoh T., Kabutoya T., Kayaba K., Kajii E. Cardiac mortality of premature ventricular complexes in healthy people in Japan. J. Cardiol. 2010;56:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muser D., Piccoli G., Puppato M., Proclemer A., Nucifora G. Incremental value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnostic work-up of patients with apparently idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias of left ventricular origin. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015;180:142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muser D., Puppato M., Proclemer A., Nucifora G. Value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the setting of familiar cardiomyopathy: A step toward pre-clinical diagnosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;203:43–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee V., Hemingway H., Harb R., Crake T., Lambiase P. The prognostic significance of premature ventricular complexes in adults without clinically apparent heart disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Heart. 2012;98:1290–1298. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dello Russo A., Pieroni M., Santangeli P., et al. Concealed cardiomyopathies in competitive athletes with ventricular arrhythmias and an apparently normal heart: Role of cardiac electroanatomical mapping and biopsy. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1915–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nucifora G., Aquaro G.D., Masci P.G., et al. Lipomatous metaplasia in ischemic cardiomyopathy: Current knowledge and clinical perspective. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011;146:120–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannavale G., Francone M., Galea N., et al. Fatty images of the heart: Spectrum of normal and pathological findings by computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. BioMed Res. Int. 2018;2018:5610347. doi: 10.1155/2018/5610347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tandri H., Castillo E., Ferrari V.A., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: Sensitivity, specificity, and observer variability of fat detection versus functional analysis of the right ventricle. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;48:2277–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aquaro G.D., Nucifora G., Pederzoli L., et al. Fat in left ventricular myocardium assessed by steady-state free precession pulse sequences. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2012;28:813–821. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eitel I., Friedrich M.G. T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute cardiac disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson Off J Soc Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:13. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim R.J., Chen E.L., Lima J.A.C., Judd R.M. Myocardial Gd-DTPA kinetics determine MRI contrast enhancement and reflect the extent and severity of myocardial injury after acute reperfused infarction. Circulation. 1996;94:3318–3326. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simonetti O.P., Kim R.J., Fieno D.S., et al. An improved MR imaging technique for the visualization of myocardial infarction. Radiology. 2001;218:215–223. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja50215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selvanayagam J., Nucifora G.G. Early and late gadolinium enhancement. The EACVI Textbook of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajiah P., Desai M.Y., Kwon D., Flamm S.D. MR imaging of myocardial infarction. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc. 2013;33:1383–1412. doi: 10.1148/rg.335125722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santangeli P., Pieroni M., Dello Russo A., et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of electroanatomic abnormalities in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:632–638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.958116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casella M., Pizzamiglio F., Dello Russo A., et al. Feasibility of combined unipolar and bipolar voltage maps to improve sensitivity of endomyocardial biopsy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:625–632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White J.A., Fine N.M., Gula L., et al. Utility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in identifying substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:12–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.966085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neilan T.G., Farhad H., Mayrhofer T., et al. Late gadolinium enhancement among survivors of sudden cardiac arrest. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015;8:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baritussio A., Zorzi A., Ghosh Dastidar A., et al. Out of hospital cardiac arrest survivors with inconclusive coronary angiogram: Impact of cardiovascular magnetic resonance on clinical management and decision-making. Resuscitation. 2017;116:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigues P., Joshi A., Williams H., et al. Diagnosis and prognosis in sudden cardiac arrest survivors without coronary artery disease CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE: Utility of a clinical approach using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:e006709. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.006709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zorzi A., Susana A., De Lazzari M., et al. Diagnostic value and prognostic implications of early cardiac magnetic resonance in survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15(7):1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krahn A.D., Healey J.S., Chauhan V., et al. Systematic assessment of patients with unexplained cardiac arrest: cardiac arrest survivors with preserved ejection fraction registry (CASPER). Circulation. 2009;120:278–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.853143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennig A., Salel M., Sacher F., et al. High-resolution three-dimensional late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to identify the underlying substrate of ventricular arrhythmia. Europace. 2018;20(FI2):f179–f191. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thachil A., Christopher J., Sastry B.K.S., et al. Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia and mediastinal adenopathy due to granulomatous infiltration in patients with preserved ventricular function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Khatib S.M., Stevenson W.G., Ackerman M.J., et al. AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017:2017. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000549. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marstrand P., Axelsson A., Thune J.J., Vejlstrup N., Bundgaard H., Theilade J. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging after ventricular tachyarrhythmias increases diagnostic precision and reduces the need for family screening for inherited cardiac disease. Europace. 2016;18(12):1860–1865. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mavrogeni S., Anastasakis A., Sfendouraki E., et al. Ventricular tachycardia in patients with family history of sudden cardiac death, normal coronaries and normal ventricular function. Can cardiac magnetic resonance add to diagnosis? Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;168:1532–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeserich M., Friedrich M.G., Olschewski M., et al. Evidence for non-ischemic scarring in patients with ventricular ectopy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011;147:482–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Globits S., Kreiner G., Frank H., et al. Significance of morphological abnormalities detected by MRI in patients undergoing successful ablation of right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. Circulation. 1997;96:2633–2640. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markowitz S.M., Litvak B.L., Ramirez de Arellano E.A., Markisz J.A., Stein K.M., Lerman B.B. Adenosine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia: Right ventricular abnormalities delineated by magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 1997;96:1192–1200. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White R.D., Trohman R.G., Flamm S.D., et al. Right ventricular arrhythmia in the absence of arrhythmogenic dysplasia: MR imaging of myocardial abnormalities. Radiology. 1998;207:743–751. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.3.9609899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carlson M.D., White R.D., Trohman R.G., et al. Right ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia: detection of previously unrecognized anatomic abnormalities using cine magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994;24:720–727. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kayser H.W., Schalij M.J., van der Wall E.E., Stoel B.C., de Roos A. Biventricular function in patients with nonischemic right ventricle tachyarrhythmias assessed with MR imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1997;169:995–999. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimm W., Wig E.H., Hoffmann J., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and signal-averaged electrocardiography in patients with repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia and otherwise normal electrocardiogram. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1997;20:1826–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tandri H., Bluemke D.A., Ferrari V.A., et al. Findings on magnetic resonance imaging of idiopathic right ventricular outflow tachycardia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004;94:1441–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tandri H., Saranathan M., Rodriguez E.R., et al. Noninvasive detection of myocardial fibrosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;45:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markowitz S.M., Weinsaft J.W., Waldman L., et al. Reappraisal of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in idiopathic outflow tract arrhythmias. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2014;25:1328–1335. doi: 10.1111/jce.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oebel S., Dinov B., Arya A., et al. ECG morphology of premature ventricular contractions predicts the presence of myocardial fibrotic substrate on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients undergoing ablation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2017;28:1316–1323. doi: 10.1111/jce.13309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeserich M., Merkely B., Olschewski M., Kimmel S., Pavlik G., Bode C. Patients with exercise-associated ventricular ectopy present evidence of myocarditis. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2015;17:100. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0204-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokokawa M., Siontis K.C., Kim H.M., et al. Value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and programmed ventricular stimulation in patients with frequent premature ventricular complexes undergoing radiofrequency ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:1695–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aljaroudi W.A., Flamm S.D., Saliba W., Wilkoff B.L., Kwon D. Role of CMR imaging in risk stratification for sudden cardiac death. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2013;6:392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dawson D.K., Hawlisch K., Prescott G., et al. Prognostic role of CMR in patients presenting with ventricular arrhythmias. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2013;6:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganesan A.N., Gunton J., Nucifora G., McGavigan A.D., Selvanayagam J.B. Impact of late gadolinium enhancement on mortality, sudden death and major adverse cardiovascular events in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018;254:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.10.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zorzi A., Marra M.P., Rigato I., et al. Nonischemic left ventricular scar as a substrate of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in competitive athletes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e004229. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aquaro G.D., Pingitore A., Strata E., Di Bella G., Molinaro S., Lombardi M. Cardiac magnetic resonance predicts outcome in patients with premature ventricular complexes of left bundle branch block morphology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56:1235–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Niwano S., Wakisaka Y., Niwano H., et al. Prognostic significance of frequent premature ventricular contractions originating from the ventricular outflow tract in patients with normal left ventricular function. Heart. 2009;95:1230–1237. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.159558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Betensky B.P., Dong W., D’Souza B.A., Zado E.S., Han Y., Marchlinski F.E. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and electroanatomic voltage discordance in non-ischemic left ventricle ventricular tachycardia and premature ventricular depolarizations. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2017;49(1):11–19. doi: 10.1007/s10840-017-0228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muser D., Liang J.J., Witschey W.R., et al. Ventricular arrhythmias associated with left ventricular noncompaction: Electrophysiologic characteristics, mapping, and ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Castro S.A., Pathak R.K., Muser D., et al. Incremental value of electroanatomical mapping for the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in a patient with sustained ventricular tachycardia. Hear Case Rep. 2016;2(6):469–472. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perin E.C., Silva G.V., Sarmento-Leite R., et al. Assessing myocardial viability and infarct transmurality with left ventricular electromechanical mapping in patients with stable coronary artery disease: Validation by delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2002;106:957–961. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000026394.01888.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gulati A., Jabbour A., Ismail T.F., et al. Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2013;309:896–908. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haaf P., Garg P., Messroghli D.R., Broadbent D.A., Greenwood J.P., Plein S. Cardiac T1 mapping and extracellular volume (ECV) in clinical practice: A comprehensive review. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2017;18(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moon J.C., Messroghli D.R., Kellman P., et al. Myocardial T1 mapping and extracellular volume quantification: A Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) and CMR working group of the European Society of Cardiology consensus statement. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson Off J Soc Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:92. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Messroghli D.R., Radjenovic A., Kozerke S., Higgins D.M., Sivananthan M.U., Ridgway J.P. Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;52:141–146. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakamori S., Bui A.H., Jang J., et al. Increased myocardial native T1 relaxation time in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy with complex ventricular arrhythmia. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2018;47(3):779–786. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mekkaoui C., Reese T.G., Jackowski M.P., Bhat H., Sosnovik D.E. Diffusion MRI in the heart: Diffusion MRI of the heart. NMR Biomed. 2017;30:e3426. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mekkaoui C., Jackowski M.P., Thiagalingam A., et al. Correlation of DTI tractography with electroanatomic mapping in normal and infarcted myocardium. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2014;16:1. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Muser D., Liang J.J., Santangeli P. Off-line analysis of electro-anatomical mapping in ventricular arrhythmias. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2017;65:369–379. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4725.17.04402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gepstein L., Goldin A., Lessick J., et al. Electromechanical characterization of chronic myocardial infarction in the canine coronary occlusion model. Circulation. 1998;98:2055–2064. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.19.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hutchinson M.D., Gerstenfeld E.P., Desjardins B., et al. Endocardial unipolar voltage mapping to detect epicardial ventricular tachycardia substrate in patients with nonischemic left ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:49–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Codreanu A., Odille F., Aliot E., et al. Electroanatomic characterization of post-infarct scars. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52:839–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Desjardins B., Crawford T., Good E., et al. Infarct architecture and characteristics on delayed enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and electroanatomic mapping in patients with post-infarction ventricular arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm Off J Heart Rhythm Soc. 2009;6:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nazarian S. Magnetic resonance assessment of the substrate for inducible ventricular tachycardia in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:2821–2825. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.549659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bogun F.M., Desjardins B., Good E., et al. Delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: Utility for identifying the ventricular arrhythmia substrate. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53:1138–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sasaki T., Miller C.F., Hansford R., et al. Impact of nonischemic scar features on local ventricular electrograms and scar-related ventricular tachycardia circuits in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6(6):1139–1147. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamashita S., Sacher F., Mahida S., et al. Image integration to guide catheter ablation in scar-related ventricular tachycardia. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2016;27(6):699–708. doi: 10.1111/jce.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andreu D., Ortiz-Pérez J.T., Boussy T., et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance in identifying the ventricular arrhythmia substrate and the approach needed for ablation. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:1316–1326. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ilg K., Baman T.S., Gupta S.K., et al. Assessment of radiofrequency ablation lesions by CMR imaging after ablation of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2010;3:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Siontis K.C., Kim H.M., Sharaf Dabbagh G., et al. Association of preprocedural cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with outcomes of ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brignole M., Moya A., de Lange F.J., et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur. Heart J. 2018;76(8):1119–8. doi: 10.5603/KP.2018.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]