Abstract

Background

Human-assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are a widely accepted treatment for infertile couples. At the same time, many studies have suggested the correlation between ART and increased incidences of normally rare imprinting disorders such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), Angelman syndrome (AS), Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), and Silver-Russell syndrome (SRS). Major methylation dynamics take place during cell development and the preimplantation stages of embryonic development. ART may prevent the proper erasure, establishment, and maintenance of DNA methylation. However, the causes and ART risk factors for these disorders are not well understood.

Results

A nationwide epidemiological study in Japan in 2015 in which 2777 pediatrics departments were contacted and a total of 931 patients with imprinting disorders including 117 BWS, 227 AS, 520 PWS, and 67 SRS patients, were recruited. We found 4.46- and 8.91-fold increased frequencies of BWS and SRS associated with ART, respectively. Most of these patients were conceived via in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and showed aberrant imprinted DNA methylation. We also found that ART-conceived SRS (ART-SRS) patients had incomplete and more widespread DNA methylation variations than spontaneously conceived SRS patients, especially in sperm-specific methylated regions using reduced representation bisulfite sequencing to compare DNA methylomes. In addition, we found that the ART patients with one of three imprinting disorders, PWS, AS, and SRS, displayed additional minor phenotypes and lack of the phenotypes. The frequency of ART-conceived Prader-Willi syndrome (ART-PWS) was 3.44-fold higher than anticipated. When maternal age was 37 years or less, the rate of DNA methylation errors in ART-PWS patients was significantly increased compared with spontaneously conceived PWS patients.

Conclusions

We reconfirmed the association between ART and imprinting disorders. In addition, we found unique methylation patterns in ART-SRS patients, therefore, concluded that the imprinting disorders related to ART might tend to take place just after fertilization at a time when the epigenome is most vulnerable and might be affected by the techniques of manipulation used for IVF or ICSI and the culture medium of the fertilized egg.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13148-019-0623-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Imprinting disorders, Assisted reproductive technologies (ART), Silver-Russell syndrome (SRS), Nationwide epidemiological study, DNA methylome, DNA methylation variations (DMVs)

Background

Human-assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are becoming increasingly common due to late marriage and improvements in medical technology in developed countries, including Japan [1]. The majority of studies published previously have suggested that babies conceived after ART have increased incidences of normally rare imprinting disorders such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), Angelman syndrome (AS), Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), and Silver-Russell syndrome (SRS) [2–7]. On the other hand, some studies found no relation between ART and imprinting disorders [8, 9]. Imprinting disorders are caused by genetic defects or epigenetic mutations (DNA methylation); i.e., aberrant DNA methylation of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) that regulate allele-specific expression of imprinted genes [10]. The relationship between ART and aberrant genomic imprinting is still unclear. However, many studies have suggested that ovarian stimulation, culture media used for gametes and early embryos, in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) manipulations, and the freezing and thawing of embryos may prevent the proper establishment and maintenance of genomic imprinting and cause imprinting disorders [11, 12].

In 2009, we performed a nationwide epidemiological study in Japan to determine the frequencies of four imprinting disorders (BWS, AS, PWS, and SRS) and found that the frequencies of ART-conceived BWS (ART-BWS) and ART-SRS patients were nearly tenfold higher than anticipated [13]. In addition, the majority of ART-SRS and ART-BWS patients showed aberrant methylation not only in domains responsible for imprinting disorders but also in additional multiple imprinted loci. Other reports have also described multi-locus imprinting disturbances after ART, supporting our hypothesis [14–16]. Furthermore, in addition to aberrant DNA methylation patterns at multiple imprinted loci, there are also mosaic methylation errors. We assumed that the imprinting errors occurred after fertilization rather than in the gametes. However, it is unknown who is predisposed to the imprinting disorders and which factor(s) of ART cause them.

In this study, we conducted another Japanese nationwide epidemiological study of the imprinting disorders in 2015 and reconfirmed the tight association between ART and imprinting disorders. Next, we studied new patients with SRS and found significant differences in the genome-wide DNA methylation between the ART patients and spontaneously conceived (Sp) patients.

Results

Relationship between the imprinting disorders and ART

We conducted a Japanese nationwide epidemiological study of four imprinting disorders to determine associations with ART. We contacted a total of 2777 pediatric departments of all hospitals that were identified based on a hospital lists. In all, 1957 departments (70.5%) responded to the first-stage survey questionnaire. We inquired about detailed clinical information and examined the relationship with ART using a second-stage survey ensuring the exclusion of duplicates and a total of 931 patients with imprinting disorders were recruited. The number, age, and gender distributions of patients are given in Additional file 1. The numbers of patients with the four imprinting disorders slightly increased year by year, especially for BWS and SRS. However, there were no differences in the gender ratios of the imprinting disorders. We ascertained the frequencies of ART-BWS, ART-AS, ART-PWS, and ART-SRS via a questionnaire sent to doctors (Table 1). The observed/expected ratios for four ART-imprinting disorders were calculated by considering the live birth rate after ART (1.34%) from 1985 through 2015 in Japan (http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jsog-art/). For BWS and SRS, the number of ART patients were 4.46- and 8.91-fold higher than anticipated, accounting for 6.0% (7/117) of BWS and 11.9% (8/67) of SRS patients, respectively. These proportions were similar to those we found in 2009 [13]. The number of ART-PWS patients was 3.44-fold higher than anticipated, but no increase in ART-AS patients was observed compared with that anticipated (1.8%, 4/227).

Table 1.

Frequency of ART in children with four imprinting disorders and observed/expected ratios of ART in the same groups

| The percentage of patients after ART/total: % (n) (2015) | Observed/expected ratios of ART | |

|---|---|---|

| BWS | 6.0% (7/117) | 4.46 |

| AS | 1.8% (4/227) | 1.32 |

| PWS | 4.6% (24/520) | 3.44 |

| SRS | 11.9% (8/67) | 8.91 |

Results of a nationwide epidemiological investigation of four imprinting disorders in Japan, under the governance of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of the Japanese government. Whether the patient was born after ART treatment was confirmed in a questionnaire. The number of patients was expected by multiplying the total number of disease patients by the live birth rate after ART (1.34%) from 1985 through 2015 in Japan (http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~jsog-art/)

In the second questionnaire, we examined the results of genetic and DNA methylation tests (Table 2 and Additional file 2). In both ART-BWS and ART-SRS patients, DNA methylation error rates were 100% (4/4 and 5/5, respectively). Additionally, that in ART-BWS was significantly higher than in spontaneously conceived BWS (Sp-BWS) patients (p = 0.027). Nearly one-half of ART-BWS (42.9%, 3/7) and the majority of ART-SRS (75%, 6/8) patients received IVF or ICSI treatment (Additional file 3). The rate of maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 (UPD(15)mat) in ART-PWS patients was significantly increased compared with that of Sp-PWS patients (p = 0.001). Next, we classified PWS patients into two categories based on maternal ages ≤ 37 years and ≥ 38 years and compared ART patients with Sp patients since the aneuploidy rate in the human embryo dramatically increases when the maternal age ≥ 38 years [17]. The rate of DNA methylation errors in ART-PWS patients was significantly increased compared with that in Sp-PWS patients for maternal age ≤ 37 years, whereas the rate of UPD(15)mat in ART-PWS patients was significantly increased compared with that in Sp-PWS patients with maternal age ≥ 38 years (p = 0.021, Table 3 and Additional file 4). There was no correlation between maternal age and UPD in BWS, AS, and SRS patients (Additional file 5).

Table 2.

Pathogeneses of four imprinting disorders

| UPD | Gene mutations | Deletions | DNA methylation errors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWS (n = 43) | ART (n = 4) | – | – | – | 100% (4/4)* |

| Sp (n = 39) | 46.2% (18/39) | 2.6% (1/39) | 7.7% (3/39) | 43.6% (17/39) | |

| AS (n = 147) | ART (n = 4) | – | – | 100% (4/4) | – |

| Sp (n = 143) | 2.1% (3/143) | 3.5% (5/143) | 92.3% (132/143) | 2.1% (3/143) | |

| PWS (n = 366) | ART (n = 21) | 42.9% (9/21)* | – | 28.6% (6/21) | 28.6% (6/21) |

| Sp (n = 345) | 13.3% (46/345) | – | 73.6% (254/345)* | 13.0% (45/345) | |

| SRS (n = 22) | ART (n = 5) | – | – | – | 100% (5/5) |

| Sp (n = 17) | 23.5% (4/17) | – | – | 76.5% (13/17) |

The numbers and percentages of patients with chromosomal abnormalities, gene mutations, and methylation abnormalities were obtained from a questionnaire. An asterisk indicates a significant difference between ART-patients and Sp-patients (p < 0.05). For BWS, UPD, and gene indicate paternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 11 and CDKN1C, and methylation errors include both gain of methylation at H19/IGF2 IG-DMR and loss of methylation at KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR, respectively. For AS, UPD, gene, and methylation error indicate paternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 15, UBE3A and loss of methylation at SNRPN-DMR, respectively. For PWS, UPD, and methylation error indicate maternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 and gain of methylation at SNRPN-DMR, respectively. For SRS, UPD, and methylation error indicate maternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 7 and loss of methylation at H19/IGF2 IG-DMR, respectively. UPD uniparental disomy

Table 3.

Frequency of different pathogeneses in ART patients and Sp patients with PWS stratified according to maternal age

| Maternal age ≤ 37 years | Maternal age ≥ 38 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART patients (n = 12) | Sp patients (n = 215) | P value | ART patients (n = 9) | Sp patients (n = 44) | P value | |

| UPD(15)mat | 16.7% (2/12) | 9.8% (21/215) | 0.348 | 77.8% (7/9) | 31.8% (14/44) | 0.021 |

| Microdeletion at chromosome15q11.5 region | 50.0% (6/12) | 79.5% (171/215) | 0.027 | 0% (0/9) | 36.4% (16/44) | 0.044 |

| DNA methylation error | 33.3% (4/12) | 10.7% (23/215) | 0.041 | 22.2% (2/9) | 31.8% (14/44) | 0.706 |

All data were obtained from the questionnaire. DNA methylation error indicates gain of methylation at SNRPN-DMR. UPD(15)mat, maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15

Phenotypic differences in patients conceived with ART

To investigate whether disease phenotypes in patients could be altered by ART, we compared the clinical features in detail. There were no major differences overall between ART patients and Sp patients for the four diseases, but there were some significant phenotypic differences (Table 4). For ART-SRS patients, the frequency of heart malformation was significantly higher (25.0%, 2/8; 3.4%, 2/59, p = 0.036) than in Sp-SRS patients. In addition, the frequency of mental retardation in ART-SRS was higher (62.5%, 5/8; 32.2%, 19/59, p = 0.124) than in Sp-SRS patients. Tumorigenesis and diabetes occurred in only one ART-SRS patient. For ART-AS patients, the frequencies of hyposomnia and ataxic gait were significantly higher (100%, 4/4; 46.2%, 103/223, p = 0.048) and lower (0%, 0/4; 60.1%, 134/223, p = 0.027), respectively, than in Sp-AS patients. For ART-PWS patients, the frequencies of dyschromatosis (91.7%, 22/24; 69.0%, 342/496, p = 0.020) and acromicria (87.5%, 21/24; 58.3%, 289/496, p = 0.005) were significantly higher and the frequency of obesity was lower (14.3%, 2/14; 49.4%, 205/415, p = 0.012) than in Sp-PWS patients. For BWS, there were some phenotypical differences between ART-BWS and Sp-BWS patients, but these were not significant.

Table 4.

Clinical phenotypic characterization of patients with ART

| ART (n = 7) | Sp (n = 110) | P value | |

| a. BWS | |||

| Macroglossia (%) | 100 | 82.7 | 0.597 |

| Earlobe creases (%) | 57.1 | 43.6 | 0.698 |

| Umbilical hernia (%) | 57.1 | 44.5 | 0.700 |

| Hemihypertrophy (%) | 28.6 | 34.5 | 1.000 |

| Exomphalos (%) | 42.9 | 22.7 | 0.356 |

| Exophthalmos (%) | 28.6 | 19.1 | 0.622 |

| Hepatomegaly (%) | 42.9 | 16.4 | 0.108 |

| Nephromegaly (%) | 14.3 | 16.4 | 1.000 |

| Ocular hypertelorism (%) | 14.3 | 13.6 | 1.000 |

| Urinary malformation (%) | 0 | 10.9 | 1.000 |

| Cryptorchism (%) | 28.6 | 10.0 | 0.174 |

| Occlusal interference (%) | 14.3 | 10.9 | 0.572 |

| Pancreatic islet hyperplasia (%) | 0 | 8.2 | 1.000 |

| Adrenomegaly (%) | 0 | 4.5 | 1.000 |

| Splenomegaly (%) | 0 | 3.6 | 1.000 |

| ART (n = 4) | Sp (n = 223) | P value | |

| b. AS | |||

| Mental retardation (%) | 100 | 98.7 | 1.000 |

| Epilepsy (%) | 100 | 65.9 | 0.304 |

| Dysphasia (%) | 100 | 89.2 | 1.000 |

| Hyposomnia (%) | 100 | 46.2 | 0.048 |

| Dyschromatosis (%) | 75.0 | 73.5 | 1.000 |

| Prognathism (%) | 50.0 | 50.7 | 1.000 |

| Convulsions (%) | 50.0 | 35.0 | 0.615 |

| Microcephaly (%) | 50.0 | 25.6 | 0.204 |

| Ictal laughter (%) | 25.0 | 57.0 | 0.320 |

| Ataxic gait (%) | 0 | 60.1 | 0.027 |

| Heart malformation (%) | 0 | 2.7 | 1.000 |

| ART (n = 24) | Sp (n = 496) | P value | |

| c. PWS | |||

| Hypotonia (%) | 100 | 86.9 | 0.059 |

| Dyschromatosis (%) | 91.7 | 69.0 | 0.020 |

| Feeding difficulties (%) | 91.7 | 79.9 | 0.194 |

| Almond-shaped eyes (%) | 87.5 | 73.6 | 0.156 |

| Acromicria (%) | 87.5 | 58.3 | 0.005 |

| Mental retardation (%) | 79.2 | 86.1 | 0.365 |

| Short stature (%) | 62.5 | 64.4 | 0.831 |

| Triangular mouth (%) | 66.7 | 61.6 | 0.673 |

| Cryptorchism (%) | 58.3 | 38.6 | 0.085 |

| Hypogonadism (%) | 50.0 | 37.4 | 0.281 |

| Bulimia (%) | 35.7 | 52.3 | 0.281 |

| Obesity (%) | 14.3 | 49.4 | 0.012 |

| Diabetes (%) | 8.3 | 12.7 | 0.755 |

| Gastrointestinal injury (%) | 8.3 | 2.8 | 0.165 |

| Cardiac failure (%) | 4.2 | 2.8 | 0.512 |

| ART (n = 8) | Sp (n = 59) | P value | |

| d. SRS | |||

| Short stature (%) | 100 | 94.9 | 1.000 |

| Failure to thrive (%) | 100 | 94.9 | 1.000 |

| Triangular shaped face (%) | 87.5 | 78.0 | 1.000 |

| Body asymmetry (%) | 87.5 | 57.6 | 0.138 |

| Clinodactyly of the fifth fingers (%) | 62.5 | 47.5 | 0.476 |

| Mental retardation (%) | 62.5 | 32.2 | 0.124 |

| Sweating (%) | 25.0 | 15.3 | 0.609 |

| Heart malformation (%) | 25.0 | 3.4 | 0.036 |

| Hypoglycemia (%) | 0 | 10.2 | 1.000 |

| Gastrointestinal injury (%) | 0 | 6.8 | 1.000 |

| Difficulty in hearing (%) | 0 | 3.4 | 1.000 |

| Ptosis (%) | 0 | 5.1 | 1.000 |

| Renal hypoplasia (%) | 0 | 1.7 | 1.000 |

| Tumorigenesis (%) | 12.5 | 0 | 0.119 |

| Diabetes (%) | 12.5 | 0 | 0.119 |

| Hypertension (%) | 0 | 1.7 | 1.000 |

The percentages of patients presenting each clinical phenotypic in four ART- and Sp-imprinting disorders: (a) BWS, (b) AS, (c) PWS, and (d) SRS. The frequencies of bulimia and obesity were calculated for PWS patients over 3 years old. The total numbers of ART-PWS and Sp-PWS patients over 3 years old were 14 and 415, respectively

Genome-wide methylation in ART-SRS patients

To investigate the genome-wide DNA methylation changes in ART-SRS patients, we performed reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) to produce DNA methylomes derived from the peripheral blood of five ART-SRS patients with H19/IGF2 intergenic (IG)-DMR hypomethylation, five Sp-SRS patients with H19/IGF2 IG-DMR hypomethylation, and ten Sp-normal children (control) who were randomly selected. We obtained an average of 3,242,341 CpG cytosines per sample and analyzed 2,069,685 CpG cytosines covered in the autosomes of all samples (Additional file 6). Global evaluations of the DNA methylation levels of all CpG cytosines in the genome among individuals of the three groups were very similar (R > 0.975), and the correlation coefficients between individuals within the ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups were greater than between individuals within the control group (Additional file 7). Among the mean methylation levels of the various genomic regions, the most methylated was in the ART-SRS group, followed in order by the Sp-SRS and control groups. The mean methylation levels of the gene bodies, exons, introns, intergenic regions, CpG island (CGI) shores, short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), long terminal repeats (LTRs), and DNA repeats in the ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups were significantly increased compared to the control group. In addition, the mean methylation levels of the CGI shelves and simple repeats in the ART-SRS group were significantly increased compared to the control group (Additional file 8).

Characterization of DMVs in ART-SRS patients

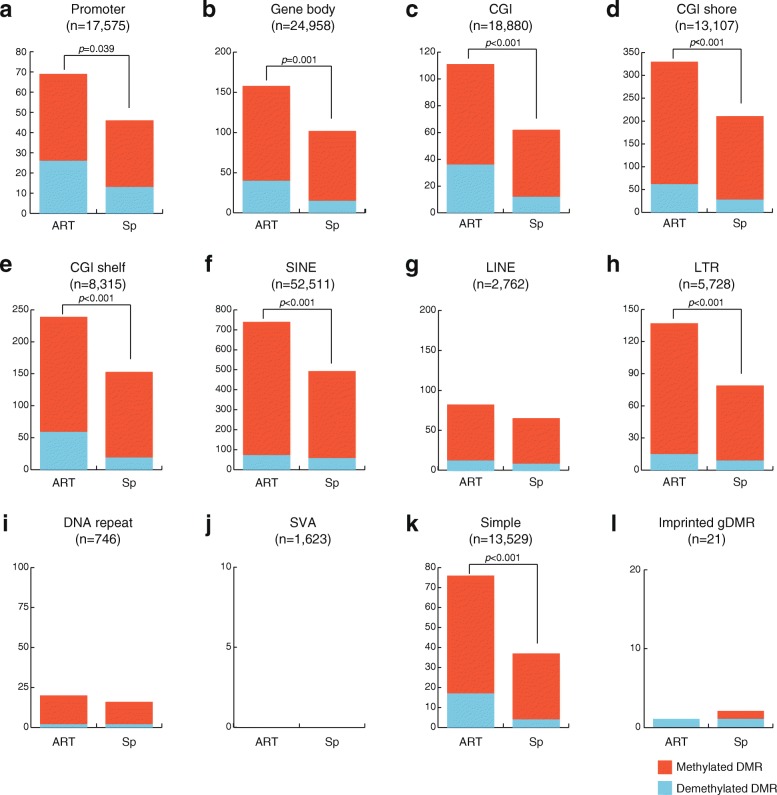

We annotated genomic regions and then identified the DNA methylation variation (DMVs) showing absolute methylation changes ≥ 7.5% and statistically significant differences (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) in the ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups compared with the control group (Fig. 1). The numbers of DMVs in the ART-SRS group were significantly increased compared with those in the Sp-SRS group in the promoter, gene body, CGI, CGI shore, CGI shelf, SINE, LTR, and simple repeat regions. In addition, the number of methylated DMVs was larger than that of demethylated DMVs in all regions. On the other hand, we found that there were no more DMVs in the ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups than in the control group for SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the numbers of DMVs in ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups. a Promoter. b Gene body. c CGI. d CGI shore. e CGI shelf. f SINE. g LINE. h LTR. i DNA repeat. j SVA. k Simple repeat. l Imprinted gDMR. Red and blue bars indicate the numbers of methylated DMVs and demethylated DMVs, respectively. DMV DNA methylation variation, CGI CpG island, SINE short interspersed nuclear element, LINE long interspersed nuclear element, LTR long terminal repeat element, SVA SINE-VNTR-Alu, gDMR germline differentially methylated region

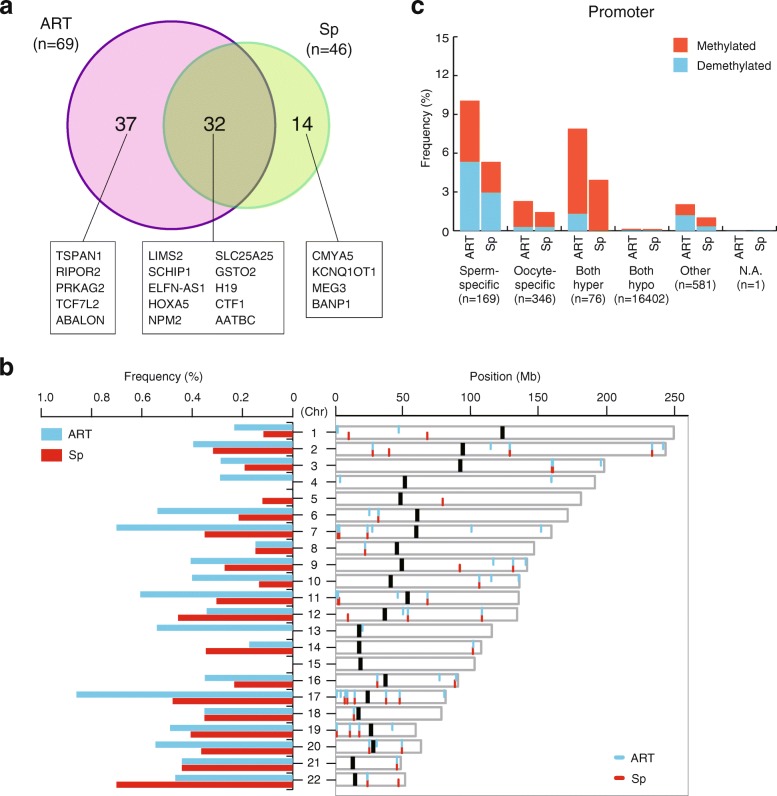

To investigate genes related to the characteristics of SRS, we next focused on promoter regions. A total of 83 promoters (corresponding to 79 genes) showed DMVs; 37 promoters (36 genes) with DMVs only in the ART-SRS group, 14 promoters (13 genes) with DMVs only in the Sp-SRS group, and 32 promoters (30 genes) with DMVs in both the ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups (Fig. 2a and Additional file 9). These promoters with DMVs were distributed in almost all autosomes (Fig. 2b). We used the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) to interpret the biological meanings of lists of ART-SRS-specific, Sp-SRS-specific, and all genes with DMVs but there were no significant gene ontology (GO) terms. However, some genes with DMVs might be associated with clinical phenotypes of SRS; therefore, we describe these genes below (see “Discussion” section).

Fig. 2.

Promoters with DMVs in SRS patients. a A Venn diagram showing 83 promoters with DMVs in SRS patients. b Autosomal chromosome frequency (left) and distribution (right) of the promoters with DMVs. Blue bars represent DMVs in ART-SRS patients and red bars represent DMVs in Sp-SRS patients. N.A. indicates that data was not available. c DMVs of promoters in ART-SRS and Sp-SRS patients classified based on methylation of gametes. Sperm-specific methylated regions were ≥ 80% methylated in sperm and ≤ 20% methylated in oocytes, oocyte-specific methylated regions were ≤ 20% methylated in sperm and ≥ 80% methylated in oocytes, both hypermethylated regions were ≥ 80% methylated in both sperm and oocytes, both hypomethylated regions were ≤ 20% methylated in both sperm and oocytes according to our previously reported data [18]

Germline-specific methylation patterns of identified DMVs in ART-SRS patients

To investigate the characteristics of DMVs identified in ART-SRS patients, we classified the DMVs into four categories: sperm-specific methylated regions ≥ 80% methylated in sperm and ≤ 20% methylated in oocytes, oocyte-specific methylated regions ≤ 20% methylated in sperm and ≥ 80% methylated in oocytes, both hypermethylated regions ≥ 80% methylated in both sperm and oocytes, and both hypomethylated regions ≤ 20% methylated in both sperm and oocytes, according to our previously reported data [18]. The proportion of DMVs occupying sperm-specific methylated regions was the highest in the promoter, gene body, CGI, CGI shelf, SINE, LTR, DNA repeat, and simple repeat regions (Fig. 2c and Additional file 10). The proportion of DMVs occupying both hypermethylated regions often followed the proportion of DMVs occupying sperm-specific methylated regions. In addition, these DMVs were incompletely (mosaic) methylated. These data suggested that the sperm-specific methylated regions were more likely to show DMVs just after fertilization in ART. Therefore, we concluded that DMVs might be affected by the techniques of the manipulation used for IVF or ICSI and the culture medium of the fertilized egg.

Discussion

Using a genome-wide approach, we demonstrated the characteristics of the DNA methylation in ART-SRS patients. They were as follows: (1) the numbers and locations of DMVs were larger and more widespread, respectively. However, some domains such as imprinted regions, SVAs, and retrotransposons had few DMVs. (2) The DMVs tended to more frequently be methylated than demethylated events. (3) The DMVs occurred more frequently in sperm-specific methylated regions. These results may suggest that ART caused the DNA methylation alterations. Major methylation dynamics take place during cell development and the preimplantation stages of embryonic development [19]. ART may prevent the proper erasure, establishment, and maintenance of DNA methylation. Recently, we and others reported that the human paternal genome is globally demethylated after fertilization, which is due to ten–eleven translocation (TET)-mediated active demethylation [18, 20–22]. On the other hand, the maternal genome is demethylated to a much lesser extent in human blastocysts, which was different from the mouse. The pattern of incomplete DMVs we observed in ART-SRS patients might indicate that the changes occurred after fertilization rather than in the gamete. Furthermore, the increased frequency of DMVs in the paternal-specific methylation domain suggested that they occurred just after fertilization.

Previously, we examined the DNA methylation status of 22 germline DMRs (gDMRs) located within the imprinted loci in an ART-BWS and five ART-SRS patients compared to those of Sp-SRS patients [13]. We observed aberrant DNA methylation patterns in the majority of ART patients (1) at multiple imprinted loci, (2) with both maternal and paternal gDMRs, (3) with both hypermethylation and hypomethylation events, and (4) mosaic methylation errors. These aberrant methylation patterns suggested that imprinting defects caused by the global demethylation after fertilization rather than in the gamete might be involved. Others also reported similar results [23, 24]. In this study, we hypothesized that the demethylation and maintenance mechanisms in the preimplantation stage might fail in ART and lead to DMVs and imprinting disorders such as BWS and SRS. Many reports have demonstrated the possibility that the process of ART might affect epigenetic alterations. For example, the phenome of large offspring syndrome has been described in bovine and sheep IVF [25]. Use of sheep embryo cultures in vitro has led to the birth of overweight male offspring with phenotypic similarity to BWS and associated with loss of imprinted methylation at IGF2R [26]. Some studies have shown that exposure of mouse embryos to different culture conditions can alter the gene expression and DNA methylation, which could result in abnormal development [27, 28]. Most recent studies have shown an association of human preimplantation embryos after ART with incorrect DNA methylation at gDMRs [29–31]. Surprisingly, day 3 embryos (76%) and blastocysts (50%) after ART had a high frequency of imprinted methylation errors at three gDMRs [31].

In this study, the frequencies of ART-BWS and ART-SRS were still high and the frequency of ART-PWS patients increased more than threefold compared to our 2009 survey [13]. Mussa et al. reported that ART entails a tenfold increased risk of BWS [6]. We reconfirmed that ART increases risk of not only BWS but also SRS and PWS. The frequency of paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 11 (UPD(11)pat) in Sp-BWS increased approximately two times compared with previous data [32]. Sasaki et al. reported that the frequency of hypomethylation in KCNQ1OT1:transcriptional start site (TTS)-DMR in Japanese BWS patients was lower than that in North American/European BWS patients [33]. In addition, we compared the frequency of UPD(11)pat in Sp-BWS patients stratified according to maternal age but there was no correlation between UPD(11)pat and maternal age. Based on the above, the increased frequency of UPD(11)pat in Sp-BWS might be due to race rather than maternal age. Matsubara et al. reported that advanced maternal age affected the onset of PWS through UPD(15)mat, resulting from a disjunction error during meiosis I in oocytes [34]. In stratified analyses of the pathogenesis of PWS according to maternal age, the rate of DNA methylation errors in ART-PWS patients was significantly increased compared with Sp-PWS patients when maternal age was ≤ 37 years, while the rate of UPD(15)mat in ART-PWS patients was significantly increased compared with that in Sp-PWS patients with maternal age ≥ 38 years. These results suggested that the increasing incidence of ART-PWS might be affected not only by maternal age but also DNA methylation altered by ART. The major pathogenesis of AS is deletion or mutation of the UBA3A gene on chromosome 15q11.2-q13 and in total the paternal UPD and imprinting defects, which might be associated with maternal age and ART, are less than 5% of the pathogenesis of AS [35]. Therefore, it may not be possible to observe the increased frequency of ART-AS in this study.

We showed that phenotypic differences between ART patients and Sp patients were largely unreported, while changes to phenotypes might be altered by the frequency and the degree of epimutations caused by ART. Lim et al. reported that ART-BWS patients had a significantly lower frequency of exomphalos and higher risk of non-Wilms’ tumor neoplasia [14]. However, we found no major differences in clinical features between the ART-BWS and Sp-BWS patients. The ART-SRS patients having defects at additional loci and DMVs other than at the domain responsible for that disorder displayed additional minor phenotypes, heart malformation, tumorigenesis, diabetes, and mental retardation. For mental retardation, Zhu et al. reported that children born after ART had a slight delay in motor and cognitive development compared with children born to infertile couples who conceived naturally, and it suggested that ART may increase the risk of mental retardation [36]. The higher frequency of mental retardation in ART-SRS patients compared with Sp-SRS patients may be affected by the risk of ART being added to the risk of SRS itself. Since it is unlikely that methylomes in peripheral blood precisely reflect phenotypes of imprinting disorders, we might not be able to clarify the relationship between phenotypes and epimutations. In addition, it may be that DMVs alone have not reached the threshold for the appearance of clinical phenotypes.

Of the 79 genes with DMVs, 19 candidate genes might be involved in clinical symptoms of SRS. TSPAN1, LIMS2, SCHIP1, HOXA5, ABALON, and AATBC genes might be involved in the growth restriction phenotype of SRS. The SCHIP1 gene is associated with facial size and shape in African children [37] and Schip1-knockout mice have skeletal, craniofacial, and digestive problems [38]. HOXA5 regulates gene expression, morphogenesis and differentiation, and upregulates the tumor suppressor p53 [39]. ABALON and AATBC are involved in apoptosis, which plays an important role in embryonic development [40]. ELEN-AS1, NPM2, GSTO2, H19, KCNQ1OT1, MEG3, and BANP might be involved in tumorigenesis. H19, KCNQ1OT1, and MEG3 are also known imprinted genes that function as tumor suppressors. The main clinical phenotype of SRS is growth retardation. A tumor is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of cells. These are opposite growth disturbances. Nevertheless, we observed tumorigenesis in ART-SRS patients in our epidemiological study. In addition, at least three papers have reported tumorigenesis in SRS patients [41–43]. Therefore, we focused on genes related to tumorigenesis. SLC25A25 and TCF7L2 might be involved in hypoglycemia. SLC25A25 encodes an ATP-Mg/Pi inner mitochondrial membrane solute transporter and Slc25a25-knockout mice are metabolically inefficient [44]. The Wnt signaling pathway regulator TCF7L2 is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and negative regulators of hepatic gluconeogenesis [45]. RIPOR2 might be involved in defective hearing since it encodes a plasma membrane-associated protein of hair cell stereocilia that is essential for hearing [46]. CMYA5, PRKAG2, and CTF1 might be involved in heart malformation. CMYA5 is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy [47]. PRKAG2 is associated with glycogen-storage cardiomyopathy [48] and CTF1 induces cardiac myocyte hypertrophy in vitro [49].

There are some limitations in this study. First, we could not recruit a sufficient number of ART patients with four imprinting disorders to compare with Sp patients for clinical phenotypes and pathogeneses and find any novel appearance for the imprinting disorders in the ART patients. However, there might be differences between the two groups that were not dealt with in our questionnaires. Second, there may be additional strong associations with imprinting disorders and ART because the details about whether or not ART treatments were employed are unknown for half of the patients with imprinting disorders. Third, we cannot provide the reasons for the use of ART for ART-associated patients because we did not inquire about the reason for using ART in the questionnaire. Fourth, we analyzed genome-wide methylation levels in peripheral blood using RRBS technology, which can only cover approximately 10% of genomic CpG cytosines. However, a strength of our study is that the sample group consisted of only Japanese subjects. The Japanese are a relatively homogeneous people geographically and traditionally, because Japan is a small island country and due to the Japanese temperament. Furthermore, genetic differences might affect clinical phenotypes and pathogeneses of imprinting disorders because they are present in the gene-specific DNA methylation levels at birth [50].

Conclusions

We demonstrated increased frequencies of ART-BWS, ART-SRS, and ART-PWS compared with the live birth rate after ART from 1985 through 2015 in Japan and the characteristics of incomplete and broader DMVs in ART-SRS patients. We reconfirmed the association between ART and three imprinting disorders (BWS, PWS, and SRS). This is perhaps not surprising given the major epigenetic events that take place during early development at a time when the epigenome is most vulnerable. The numbers of children with imprinting disorders born after ART treatment remain limited and the vast majority of children born after such treatments are healthy. On the other hand, it is also well known that epigenetic alterations can increase the risks for various diseases later in life such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension [51]. Further large-scale, long-term studies will be needed to determine the associations with epimutations and phenotypes of children conceived after ART.

Materials and methods

Nationwide search of four congenital imprinting disorders

The protocol was almost the same as that we used previously and was established by the Research Committee on the Epidemiology of Intractable Diseases. The nationwide survey used a two-stage postal method [13]. First, a survey was conducted to estimate the number of individuals with any of the four imprinting diseases: BWS, SRS, PWS, and AS. In the following stage, a second survey was used to identify the clinico-epidemiological features of these syndromes. We previously reported the questionnaires in detail [13].

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing

Genomic DNA was obtained from whole blood using the standard extraction protocol and treated with PureLink RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The DNA was used for reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) library construction as previously described with modifications [52]. Briefly, 20 ng of genomic DNA was digested with 20 units of MspI enzymes (NEB, Beverly, MA, USA) in 15 μl reactions with 1x NEBuffer 2 at 37 °C for 16 h and 80 °C for 20 min. The digested products were filled in, and an adenosine was added with 10 units of Klenow Fragment (3′ → 5′ exo−, NEB), 4 μM dGTP, 4 μM dCTP, 40 μM dATP, and 1× NEBuffer 2 to a final volume of 17 μl. The end-repaired/dA-tailing reaction was incubated at 30 °C for 20 min, 37 °C for 20 min, and 75 °C for 20 min. The end-repaired fragments were immediately ligated to 1 μM pre-annealed methylated adaptors using 2000 cohesive end units of T4 DNA Ligase (NEB) in 20 μl reactions with 1× Ligase Reaction Buffer. The ligation reactions were incubated at 16 °C for 16 h and 65 °C for 20 min. The ligated products were separated on 3% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel (Lonza Japan, Tokyo, Japan) by electrophoresis to isolate 150–350 bp fragments and size-selected fragments were extracted and purified using a MinElute Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and 20 μl of warmed EB buffer. Then bisulfite conversion was performed using an EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen). To incorporate the sample-specific index and amplify the library, PCR was performed with KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA). The PCR amplification was carried out as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 14 cycles of 98 °C for 20 s, 65 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final 1-min extension at 72 °C. The RRBS libraries were purified twice using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), quantified with KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Kapa Biosystems), and sequenced on an HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina, CA, USA) with 101-bp single-end reads using a TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS and TruSeq SBS Kit v3-HS (Illumina). Sequenced reads were processed using an Illumina standard base-calling pipeline (v1.8.2) and the index and adapter sequences were removed. After trimming the first and last four bases, the reads were aligned to Human Genome assembly (GrCh37/hg19) using Bismark (v.0.9.0) with default parameters [53]. Reads that showed < 90% bisulfite conversion were filtered to remove those that resulted from incomplete bisulfite-converted molecules. The methylation level of each cytosine was calculated using the Bismark methylation extractor. We analyzed only CpG cytosines covered with ≥ 5 reads.

Annotations of genomic regions

Annotations of Refseq genes and repeat sequences were downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/). Refseq genes shorter than 300 bp (encoding microRNAs or small nucleolar RNAs) were excluded from our analyses. Promoters were defined as regions 500 bp upstream and downstream from the transcription start sites of the Refseq transcripts. For calculation of the mean methylation levels, we analyzed the genomic regions (promoters, exons, introns, intergenic regions, imprinted gDMRs, CGIs, CGI shores, and CGI shelves) containing ≥ 10 CpG cytosines and SINEs, LINEs, LTRs, DNA repeats, SVAs, and simple repeats containing ≥ 3 CpG cytosines with sufficient coverage for calculation of the methylation levels. Regions and names of the 21 imprinted gDMRs were defined as previously reported [54].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R or JMP Pro 13.1.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance among the clinical characteristics was determined using Fisher’s exact test or the Mann–Whitney U test at p < 0.05. Correlations of all CpG cytosines among individual ART-SRS patients, Sp-SRS patients, and ten spontaneously conceived normal children (control) were calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical significance in the mean methylation levels of various genomic regions among the three groups was determined using Steel’s test at p < 0.05. Using the Mann–Whitney U test with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction, we selected the DNA methylation variations (DMVs) showing absolute methylation changes ≥ 7.5% and a FDR < 0.05. Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the p values for the number of DMVs. Fisher’s exact test with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to calculate the p values for enriched GO terms in DAVID analysis [55].

Additional files

The numbers and age distributions of patients with the four imprinting diseases. (a) BWS. (b) AS. (c) PWS. (d) SRS. The vertical axis shows the number of patients and the horizontal axis shows age. (JPG 1026 kb)

Flowchart showing the molecular testing in four imprinted disorders. (a) BWS. (b) AS. (c) PWS. (d) SRS. The new BWS consensus score [32] and the Netchine-Harbison clinical scoring system (NH-CSS) were used for the diagnoses of BWS and SRS, respectively. NH-CSS, Netchine-Harbison clinical scoring system; UPD, uniparental disomy; GOM, gain of methylation; LOM, loss of methylation. (JPG 1285 kb)

Clinical characterization of ART-patients. OI/TI, ovulation induction/timed intercourse; IUI, intrauterine insemination; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection. N.A. indicates that data was not available. Clinical features were as follows, 1. Macroglossia, 2. Earlobe creases, 3. Umbilical hernia, 4. Hemihypertrophy, 5. Exomphalos, 6. Exophthalmos, 7. Hepatomegaly, 8. Nephromegaly, 9. Ocular hypertelorism, 10. Cryptorchism, 11. Occlusal interference, 12. Mental retardation, 13. Epilepsy, 14. Dysphasia, 15. Dyschromatosis, 16. Ictal laughter, 17. Prognathism, 18. Hyposomnia, 19. Convulsions, 20. Microcephaly, 21. Hypotonia, 22. Feeding difficulties, 23. Almond-shaped eyes, 24. Short stature, 25. Triangular mouse, 26. Acromicria, 27. Bulimia, 28. Obesity, 29. Hypogonadism, 30. Diabetes, 31. Gastrointestinal injury, 32. Cardiac failure, 33. Failure to thrive, 34. Triangular-shaped face, 35. Body asymmetry, 36. Clinodactyly of the fifth fingers, 37. Sweating, 38. Heart malformation. 39. Tumorigenesis. (XLSX 12 kb)

Frequency of different prevalence of UPD(15)mat and DNA methylation error in ART-patients and Sp-patients with PWS according to maternal age. All data were obtained from the questionnaire. DNA methylation error indicates gain of methylation at SNRPN-DMR. UPD(15)mat, maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15. (XLSX 11 kb)

Frequency of different pathogeneses in ART-patients and Sp-patients with BWS, AS and SRS stratified according to maternal age. (a) BWS. (b) AS. (c) SRS. The numbers and percentages of patients with chromosomal abnormalities, gene mutations and methylation abnormalities were obtained from a questionnaire. For BWS, UPD and gene indicate paternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 11 and CDKN1C, and methylation errors include both gain of methylation at H19/IGF2 IG-DMR and loss of methylation (LOM) at KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR, respectively. For AS, UPD and gene indicate paternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 and UBE3A, respectively. For SRS, UPD and methylation error indicate maternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 7 and LOM at H19/IGF2 IG-DMR, respectively. UPD, uniparental disomy; LOM, loss of methylation. (XLSX 11 kb)

Sequencing information. (XLSX 10 kb)

Correlations of the methylation levels of all CpG cytosines covered in all samples. (JPG 832 kb)

Methylation levels of various genomic features in autosomes. Mean methylation levels (%) of CpG cytosines in the promoter, gene body, exon, intron, intergenic region, CGI, CGI shore, CGI shelf, SINE, LINE, LTR, DNA repeat element, SVA and simple repeat. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Since the numbers of ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups were small, we did not calculate p-values between two groups. SINE, short interspersed nuclear element; LINE, long interspersed nuclear element; LTR, long terminal repeat element; SVA, SINE-VNTR-Alu. (XLSX 11 kb)

Lists of DMVs in various genomic regions. N.A. indicates that data was not available. (XLSX 1005 kb)

DMVs in ART-SRS and Sp-SRS patients classified based on methylation of gametes. Sperm-specific methylated regions were ≥ 80% methylated in sperm and ≤ 20% methylated in oocytes, oocyte-specific methylated regions were ≤ 20% methylated in sperm and ≥ 80% methylated in oocytes, both hypermethylated regions were ≥ 80% methylated in both sperm and oocytes, both hypomethylated regions were ≤ 20% methylated in both sperm and oocytes according to our previously reported data [18]. N.A. indicates that data was not available. (JPG 1269 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the individuals, their families, and medical doctors who participated in this study. We would also like to thank Dr. K. Nakayama, Dr. R. Funayama, Ms. M. Tsuda, Ms. M. Kikuchi, Ms. M. Nakagawa, and Mr. K. Kuroda for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED: JP17ek0109132h0003 to TA) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI: 17H04335 to TA).

Availability of data and materials

All sequence data have been deposited in the DDBJ Japanese Genotype-phenotype Archive under the accession number DRA007187.

Abbreviations

- ART

Assisted reproductive technologies

- AS

Angelman syndrome

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BWS

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

- CGI

CpG island

- DAVID

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- DDBJ

DNA Data Bank of Japan

- DMR

Differentially methylated region

- DMV

DNA methylation variation

- FDR

False discovery rate

- gDMR

Germline differentially methylated region

- GO

Gene ontology

- ICSI

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- IG

Intergenic

- IVF

In vitro fertilization

- LINE

Long interspersed nuclear element

- LTR

Long terminal repeat

- N.A.

Not available

- PWS

Prader-Willi syndrome

- RRBS

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing

- SINE

Short interspersed nuclear element

- Sp

Spontaneously conceived

- SRS

Silver-Russell syndrome

- SVA

SINE-VNTR-Alu

- TET

Ten–eleven translocation

- TSS

Transcriptional start site

- UPD

Uniparental disomy

- UPD(11)pat

Paternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 11

- UPD(15)mat

Maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15

- VNTR

Variable number of tandem repeat

Authors’ contributions

HHa, HHi, and NM performed data analysis of epidemiological study. HHi, HO, NK, AK, and NM performed the DNA methylation analyses. AK, NM, ST, MK, TO, and TA collected the samples of the patients. HHi, HHa, and NK did the statistical analyses. HHa, HHi, KK, and TA wrote this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tohoku University School of Medicine (2015-1-130, 2015-1-735, 2017-1-880, 2018-1-81). All samples were obtained after receiving written informed consent. All experiments handling human blood cells were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dyer S, Chambers GM, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG, Zegers-Hochschild F, Mansour R, Ishihara O, Banker M, Adamson GD. International committee for monitoring assisted Reproductive technologies world report: assisted reproductive technology 2008, 2009 and 2010. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(7):1588–1609. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucifero D, Chaillet JR, Trasler JM. Potential significance of genomic imprinting defects for reproduction and assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(1):3–18. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiba H, Hiura H, Okae H, Miyauchi N, Sato F, Sato A, Arima T. DNA methylation errors in imprinting disorders and assisted reproductive technology. Pediatr Int. 2013;55(5):542–549. doi: 10.1111/ped.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsubara K, Murakami N, Fukami M, Kagami M, Nagai T, Ogata T. Risk assessment of medically assisted reproduction and advanced maternal ages in the development of Prader-Willi syndrome due to UPD(15)mat. Clin Genet. 2016;89(5):614–619. doi: 10.1111/cge.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortessis VK, Azadian M, Buxbaum J, Sanogo F, Song AY, Sriprasert I, Wei PC, Yu J, Chung K, Siegmund KD. Comprehensive meta-analysis reveals association between multiple imprinting disorders and conception by assisted reproductive technology. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(6):943–952. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mussa A, Molinatto C, Cerrato F, Palumbo O, Carella M, Baldassarre G, Carli D, Peris C, Riccio A, Ferrero GB. Assisted Reproductive Techniques and Risk of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20164311. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Uk A, Collardeau-Frachon S, Scanvion Q, Michon L, Amar E. Assisted reproductive technologies and imprinting disorders: results of a study from a French congenital malformations registry. Eur J Med Genet. 2018;61(9):518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lidegaard O, Pinborg A, Andersen AN. Imprinting diseases and IVF: Danish national IVF cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):950–954. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doornbos ME, Maas SM, McDonnell J, Vermeiden JP, Hennekam RC. Infertility, assisted reproduction technologies and imprinting disturbances: a Dutch study. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(9):2476–2480. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler MG. Genomic imprinting disorders in humans: a mini-review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26(9–10):477–486. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9353-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiura H, Okae H, Chiba H, Miyauchi N, Sato F, Sato A, Arima T. Imprinting methylation errors in ART. Reproductive Med Biol. 2014;13(4):193–202. doi: 10.1007/s12522-014-0183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uyar A, Seli E. The impact of assisted reproductive technologies on genomic imprinting and imprinting disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26(3):210–221. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiura H, Okae H, Miyauchi N, Sato F, Sato A, Van De Pette M, John RM, Kagami M, Nakai K, Soejima H, et al. Characterization of DNA methylation errors in patients with imprinting disorders conceived by assisted reproduction technologies. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2541–2548. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim D, Bowdin SC, Tee L, Kirby GA, Blair E, Fryer A, Lam W, Oley C, Cole T, Brueton LA, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic features of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome associated with assisted reproductive technologies. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(3):741–747. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tee L, Lim DH, Dias RP, Baudement MO, Slater AA, Kirby G, Hancocks T, Stewart H, Hardy C, Macdonald F, et al. Epimutation profiling in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: relationship with assisted reproductive technology. Clin Epigenetics. 2013;5(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eggermann T, Heilsberg AK, Bens S, Siebert R, Beygo J, Buiting K, Begemann M, Soellner L. Additional molecular findings in 11p15-associated imprinting disorders: an urgent need for multi-locus testing. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92(7):769–777. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fragouli E, Alfarawati S, Spath K, Jaroudi S, Sarasa J, Enciso M, Wells D. The origin and impact of embryonic aneuploidy. Hum Genet. 2013;132(9):1001–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okae H, Chiba H, Hiura H, Hamada H, Sato A, Utsunomiya T, Kikuchi H, Yoshida H, Tanaka A, Suyama M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation dynamics during early human development. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(12):e1004868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messerschmidt DM, Knowles BB, Solter D. DNA methylation dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the germline and preimplantation embryos. Genes Dev. 2014;28(8):812–828. doi: 10.1101/gad.234294.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo H, Zhu P, Yan L, Li R, Hu B, Lian Y, Yan J, Ren X, Lin S, Li J, et al. The DNA methylation landscape of human early embryos. Nature. 2014;511(7511):606–610. doi: 10.1038/nature13544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith ZD, Chan MM, Humm KC, Karnik R, Mekhoubad S, Regev A, Eggan K, Meissner A. DNA methylation dynamics of the human preimplantation embryo. Nature. 2014;511(7511):611–615. doi: 10.1038/nature13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu P, Guo H, Ren Y, Hou Y, Dong J, Li R, Lian Y, Fan X, Hu B, Gao Y, et al. Single-cell DNA methylome sequencing of human preimplantation embryos. Nat Genet. 2018;50(1):12–19. doi: 10.1038/s41588-017-0007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossignol S, Steunou V, Chalas C, Kerjean A, Rigolet M, Viegas-Pequignot E, Jouannet P, Le Bouc Y, Gicquel C. The epigenetic imprinting defect of patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome born after assisted reproductive technology is not restricted to the 11p15 region. J Med Genet. 2006;43(12):902–907. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.042135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bliek J, Verde G, Callaway J, Maas SM, De Crescenzo A, Sparago A, Cerrato F, Russo S, Ferraiuolo S, Rinaldi MM, et al. Hypomethylation at multiple maternally methylated imprinted regions including PLAGL1 and GNAS loci in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Human Genet. 2009;17(5):611–619. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young LE, Sinclair KD, Wilmut I. Large offspring syndrome in cattle and sheep. Rev Reprod. 1998;3(3):155–163. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0030155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young LE, Fernandes K, McEvoy TG, Butterwith SC, Gutierrez CG, Carolan C, Broadbent PJ, Robinson JJ, Wilmut I, Sinclair KD. Epigenetic change in IGF2R is associated with fetal overgrowth after sheep embryo culture. Nat Genet. 2001;27(2):153–154. doi: 10.1038/84769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doherty AS, Mann MR, Tremblay KD, Bartolomei MS, Schultz RM. Differential effects of culture on imprinted H19 expression in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Biol Reprod. 2000;62(6):1526–1535. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khosla S, Dean W, Brown D, Reik W, Feil R. Culture of preimplantation mouse embryos affects fetal development and the expression of imprinted genes. Biol Reprod. 2001;64(3):918–926. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.3.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen SL, Shi XY, Zheng HY, Wu FR, Luo C. Aberrant DNA methylation of imprinted H19 gene in human preimplantation embryos. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2356–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi X, Chen S, Zheng H, Wang L, Wu Y. Abnormal DNA methylation of imprinted loci in human preimplantation embryos. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(8):978–983. doi: 10.1177/1933719113519173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White CR, Denomme MM, Tekpetey FR, Feyles V, Power SG, Mann MR. High frequency of imprinted methylation errors in human preimplantation embryos. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17311. doi: 10.1038/srep17311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brioude F, Kalish JM, Mussa A, Foster AC, Bliek J, Ferrero GB, Boonen SE, Cole T, Baker R, Bertoletti M, et al. Expert consensus document: clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: an international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):229–249. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki K, Soejima H, Higashimoto K, Yatsuki H, Ohashi H, Yakabe S, Joh K, Niikawa N, Mukai T. Japanese and North American/European patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome have different frequencies of some epigenetic and genetic alterations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15(12):1205–1210. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsubara K, Murakami N, Nagai T, Ogata T. Maternal age effect on the development of Prader-Willi syndrome resulting from upd(15)mat through meiosis 1 errors. J Hum Genet. 2011;56(8):566–571. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buiting K, Williams C, Horsthemke B. Angelman syndrome—insights into a rare neurogenetic disorder. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(10):584–593. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu JL, Basso O, Obel C, Hvidtjorn D, Olsen J. Infertility, infertility treatment and psychomotor development: the Danish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(2):98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole JB, Manyama M, Kimwaga E, Mathayo J, Larson JR, Liberton DK, Lukowiak K, Ferrara TM, Riccardi SL, Li M, et al. Genomewide association study of African children identifies association of SCHIP1 and PDE8A with facial size and shape. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(8):e1006174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmahl J, Raymond CS, Soriano P. PDGF signaling specificity is mediated through multiple immediate early genes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):52–60. doi: 10.1038/ng1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeannotte L, Gotti F, Landry-Truchon K. Hoxa5: a key player in development and disease. J Dev Biol. 2016;4(2):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Brill A, Torchinsky A, Carp H, Toder V. The role of apoptosis in normal and abnormal embryonic development. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1999;16(10):512–519. doi: 10.1023/A:1020541019347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Draznin MB, Stelling MW, Johanson AJ. Silver-Russell syndrome and craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr. 1980;96(5):887–889. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(80)80570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss GR, Garnick MB. Testicular cancer in a Russell-Silver dwarf. J Urol. 1981;126(6):836–837. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)54773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chitayat D, Friedman JM, Anderson L, Dimmick JE. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a child with familial Russell-Silver syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1988;31(4):909–914. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320310425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anunciado-Koza RP, Zhang J, Ukropec J, Bajpeyi S, Koza RA, Rogers RC, Cefalu WT, Mynatt RL, Kozak LP. Inactivation of the mitochondrial carrier SLC25A25 (ATP-Mg2+/Pi transporter) reduces physical endurance and metabolic efficiency in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):11659–11671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ip W, Shao W, Chiang YT, Jin T. The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 is upregulated by insulin and represses hepatic gluconeogenesis. Am J Phys Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(9):E1166–E1176. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00249.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz-Horta O, Subasioglu-Uzak A, Grati M, DeSmidt A, Foster J, 2nd, Cao L, Bademci G, Tokgoz-Yilmaz S, Duman D, Cengiz FB, et al. FAM65B is a membrane-associated protein of hair cell stereocilia required for hearing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(27):9864–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401950111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagami H, Kikuchi Y, Katsuya T, Morishita R, Akasaka H, Saitoh S, Rakugi H, Kaneda Y, Shimamoto K, Ogihara T. Gene polymorphism of myospryn (cardiomyopathy-associated 5) is associated with left ventricular wall thickness in patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2007;30(12):1239–1246. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arad M, Maron BJ, Gorham JM, Johnson WH, Jr, Saul JP, Perez-Atayde AR, Spirito P, Wright GB, Kanter RJ, Seidman CE, et al. Glycogen storage diseases presenting as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(4):362–372. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pennica D, King KL, Shaw KJ, Luis E, Rullamas J, Luoh SM, Darbonne WC, Knutzon DS, Yen R, Chien KR, et al. Expression cloning of cardiotrophin 1, a cytokine that induces cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(4):1142–1146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adkins RM, Krushkal J, Tylavsky FA, Thomas F. Racial differences in gene-specific DNA methylation levels are present at birth. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91(8):728–736. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bateson P, Barker D, Clutton-Brock T, Deb D, D'Udine B, Foley RA, Gluckman P, Godfrey K, Kirkwood T, Lahr MM, et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature. 2004;430(6998):419–421. doi: 10.1038/nature02725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi N, Okae H, Hiura H, Chiba H, Shirakata Y, Hara K, Tanemura K, Arima T. Genome-scale assessment of age-related DNA methylation changes in mouse spermatozoa. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0167127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krueger F, Andrews SR. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(11):1571–1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Court F, Tayama C, Romanelli V, Martin-Trujillo A, Iglesias-Platas I, Okamura K, Sugahara N, Simon C, Moore H, Harness JV, et al. Genome-wide parent-of-origin DNA methylation analysis reveals the intricacies of human imprinting and suggests a germline methylation-independent mechanism of establishment. Genome Res. 2014;24(4):554–569. doi: 10.1101/gr.164913.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang d W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The numbers and age distributions of patients with the four imprinting diseases. (a) BWS. (b) AS. (c) PWS. (d) SRS. The vertical axis shows the number of patients and the horizontal axis shows age. (JPG 1026 kb)

Flowchart showing the molecular testing in four imprinted disorders. (a) BWS. (b) AS. (c) PWS. (d) SRS. The new BWS consensus score [32] and the Netchine-Harbison clinical scoring system (NH-CSS) were used for the diagnoses of BWS and SRS, respectively. NH-CSS, Netchine-Harbison clinical scoring system; UPD, uniparental disomy; GOM, gain of methylation; LOM, loss of methylation. (JPG 1285 kb)

Clinical characterization of ART-patients. OI/TI, ovulation induction/timed intercourse; IUI, intrauterine insemination; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection. N.A. indicates that data was not available. Clinical features were as follows, 1. Macroglossia, 2. Earlobe creases, 3. Umbilical hernia, 4. Hemihypertrophy, 5. Exomphalos, 6. Exophthalmos, 7. Hepatomegaly, 8. Nephromegaly, 9. Ocular hypertelorism, 10. Cryptorchism, 11. Occlusal interference, 12. Mental retardation, 13. Epilepsy, 14. Dysphasia, 15. Dyschromatosis, 16. Ictal laughter, 17. Prognathism, 18. Hyposomnia, 19. Convulsions, 20. Microcephaly, 21. Hypotonia, 22. Feeding difficulties, 23. Almond-shaped eyes, 24. Short stature, 25. Triangular mouse, 26. Acromicria, 27. Bulimia, 28. Obesity, 29. Hypogonadism, 30. Diabetes, 31. Gastrointestinal injury, 32. Cardiac failure, 33. Failure to thrive, 34. Triangular-shaped face, 35. Body asymmetry, 36. Clinodactyly of the fifth fingers, 37. Sweating, 38. Heart malformation. 39. Tumorigenesis. (XLSX 12 kb)

Frequency of different prevalence of UPD(15)mat and DNA methylation error in ART-patients and Sp-patients with PWS according to maternal age. All data were obtained from the questionnaire. DNA methylation error indicates gain of methylation at SNRPN-DMR. UPD(15)mat, maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15. (XLSX 11 kb)

Frequency of different pathogeneses in ART-patients and Sp-patients with BWS, AS and SRS stratified according to maternal age. (a) BWS. (b) AS. (c) SRS. The numbers and percentages of patients with chromosomal abnormalities, gene mutations and methylation abnormalities were obtained from a questionnaire. For BWS, UPD and gene indicate paternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 11 and CDKN1C, and methylation errors include both gain of methylation at H19/IGF2 IG-DMR and loss of methylation (LOM) at KCNQ1OT1:TSS-DMR, respectively. For AS, UPD and gene indicate paternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 and UBE3A, respectively. For SRS, UPD and methylation error indicate maternally uniparental disomy of chromosome 7 and LOM at H19/IGF2 IG-DMR, respectively. UPD, uniparental disomy; LOM, loss of methylation. (XLSX 11 kb)

Sequencing information. (XLSX 10 kb)

Correlations of the methylation levels of all CpG cytosines covered in all samples. (JPG 832 kb)

Methylation levels of various genomic features in autosomes. Mean methylation levels (%) of CpG cytosines in the promoter, gene body, exon, intron, intergenic region, CGI, CGI shore, CGI shelf, SINE, LINE, LTR, DNA repeat element, SVA and simple repeat. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Since the numbers of ART-SRS and Sp-SRS groups were small, we did not calculate p-values between two groups. SINE, short interspersed nuclear element; LINE, long interspersed nuclear element; LTR, long terminal repeat element; SVA, SINE-VNTR-Alu. (XLSX 11 kb)

Lists of DMVs in various genomic regions. N.A. indicates that data was not available. (XLSX 1005 kb)

DMVs in ART-SRS and Sp-SRS patients classified based on methylation of gametes. Sperm-specific methylated regions were ≥ 80% methylated in sperm and ≤ 20% methylated in oocytes, oocyte-specific methylated regions were ≤ 20% methylated in sperm and ≥ 80% methylated in oocytes, both hypermethylated regions were ≥ 80% methylated in both sperm and oocytes, both hypomethylated regions were ≤ 20% methylated in both sperm and oocytes according to our previously reported data [18]. N.A. indicates that data was not available. (JPG 1269 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All sequence data have been deposited in the DDBJ Japanese Genotype-phenotype Archive under the accession number DRA007187.