Abstract

Background

In South Asia, the epidemiology of malaria is complex, and transmission mainly occurs in remote areas near international borders. Vector control has been implemented as a key strategy in malaria prevention for decades. A rising threat to the efficacy of vector control efforts is the development of insecticide resistance, thus it is important to monitor the type and frequency of insecticide resistant alleles in the disease vectors such as An. sinensis along the China-Vietnam border. Such information is needed to synthesize effective malaria vector control strategies.

Methods

A total of 208 adults of An. sinensis, collected from seven sites in southwest Guangxi along the China-Vietnam border, were inspected for the resistance-conferring G119S mutation in acetylcholinesterase (AChE) by PCR-RFLP (polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism) and kdr mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) by sequencing. In addition, the evolutionary origin of An. sinensis vgsc gene haplotypes was analyzed using Network 5.0.

Results

The frequencies of mutant 119S of AChE were between 0.61–0.85 in the seven An. sinensis populations. No susceptible homozygote (119GG) was detected in three of the seven sites (DXEC, LZSK and FCGDX). Very low frequencies of kdr (0.00–0.01) were detected in the seven populations, with most individuals being susceptible homozygote (1014LL). The 1014F mutation was detected only in the southeast part (FCGDX) at a low frequency of 0.03. The 1014S mutation was distributed in six of the seven populations with frequencies ranging from 0.04 to 0.08, but absent in JXXW. Diverse haplotypes of 1014L and 1014S were found in An. sinensis along the China-Vietnam border, while only one 1014F haplotype was detected in this study. Consistent with a previous report, resistant 1014S haplotypes did not have a single origin.

Conclusions

The G119S mutation of AChE was present at high frequencies (0.61–0.85) in the An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border, suggesting that the vector control authorities should be cautious when considering carbamates and organophosphates as chemicals for vector control. The low frequencies (0.00–0.11) of kdr in these populations suggest that pyrethroids remain suitable for use against An. sinensis in these regions.

Keywords: Anopheles sinensis, Haplotype, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China-Vietnam border, G119S, Knockdown resistance (kdr), Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), Voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC)

Background

Malaria is a deadly vector-borne disease in tropical and subtropical regions, with 216 million malaria cases and 445,000 deaths reported in 2016 worldwide [1]. In Vietnam, 14,941 confirmed malaria cases were recorded in 2014 [2], while neighboring China is on-track to eliminate malaria by 2020 [3]. One major obstacle to elimination is the importation of malaria parasites in infected travelers which was seen in returning workers from Africa and Southeast Asia [3]. Furthermore, frequent population movement across the China-Vietnam border is a factor that poses a risk of malaria transmission and re-emergence, particularly in the adjacent Province of Guangxi. Considering that vector control remains a key strategy in malaria prevention and that its efficacy is threatened by the increasing resistance of vectors to available insecticides, there is a need to assess the actual occurrence of insecticide resistance-associated genetic mutations in Guangxi An. sinensis along the China-Vietnam border.

Carbamate (CM) and organophosphorate (OP) insecticides target insect acetylcholinesterases (AChEs). These insecticides interfere in the normal neurotransmission of insects through inhibiting the activity of AChE [4–6]. Related studies have demonstrated that G119S substitution in AChE (AChE-G119S) is associated with insect resistance to OP and CM [7–11]. Recent surveys have revealed that the G119S occurs at high frequencies in many field populations of An. sinensis in Asia [12, 13].

Insect voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC) are the targets of a variety of insecticides including pyrethroid (PY) and organochlorine (OC) insecticides [14–16]. It has been characterized that point mutations can reduce the sensitivity of VGSCs to insecticides, thus leading to insecticide resistance [15]. Several conserved insecticide resistance-related amino acid substitutions have been documented, such as leucine (L) to phenylalanine (F) at the 1014th amino acid of VGSC [17]. L1014F is the most common mutation in VGSC in anopheline mosquitoes in Africa, Asia and America. In addition to 1014F, other two mutations (1014S and 1014C) were detected in An. sinensis from Asia, including China [16, 18–20]. Interestingly, kdr frequencies in samples from western Guangxi of China were low, while those in samples from northeast Guangxi were high [20]. 1014S was also present in An. sinensis samples from southern Vietnam [21].

In this study, insecticide resistance conferring mutations in ace-1 (encoding AChE) and vgsc genes were investigated in An. sinensis adult samples collected from seven sites in Guangxi along the China-Vietnam border. In addition, the possible evolutionary origin of kdr haplotypes was analyzed.

Methods

The seven sample-collecting sites were located in different villages of Guangxi near the Chinese-Vietnamese border (Fig. 1). Rice is the main crop planted in these villages. The large area of rice field provides an excellent environment for mosquito breeding. The local residents usually use mosquito nets and sometimes mosquito coils (containing S-bioallethrin or prallethrin) to prevent mosquito bites. The commonly used insecticides for rice pest control in these areas are diamides (e.g. chlorantraniliprole), neonicotinoids (e.g. imidacloprid) and organophosphorates (e.g. acephate and dimethoate).

Fig. 1.

Distribution and frequency of ace and kdr alleles in An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border. Abbreviations: NPPM, Pingmeng, Napo County; JXXW, Xinwei, Jingxi County; JXTD, Tongde, Jingxi County; DXEC, Encheng, Daxin County; LZSK, Shuikou, Longzhou County; PXSS, Shangshi, Pingxiang County; FCGDX, Dongxing town, Fangchenggang City

Anopheles sinensis adults used in the study were caught by light trap (wave length 365 nm) between April 2015 and August 2017 at seven sites. At each sampling site, three houses were equipped with a light trap (one trap per house). The distance between houses was more than 50 m. The light trap was placed in the bedroom (1.5–2.0 m above the ground). The mosquitoes trapped from 19:00 h to 7:00 h for consecutive three days from each site were pooled, morphologically identified [22], and kept in 100% ethanol at 4 °C. Up to 33 An. sinensis were used for genotyping from each trapping effort.

The genomic DNA of individual mosquitoes was isolated according to the protocol described by Rinkevinch et al. [23]. Genotyping of codon 119 of An. sinensis ace-1 gene was done by PCR-RFLP [12]. The frequency of the G119S mutation in each collection was recorded. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested using the online software GENEPOP v.4.2 [24, 25].

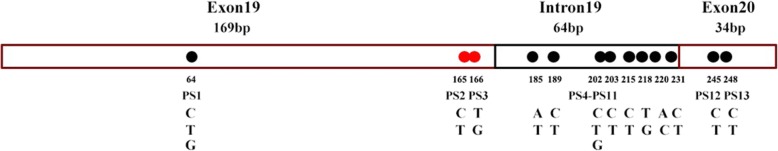

A fragment encompassing nucleotides corresponding to codon 1014 was amplified by PCR [20]. The PCR product from each individual was directly sequenced. Data from each sequencing was checked and cleaned manually. All confirmed DNA sequences were aligned using the Muscle programme in Mega v.6.0 [26], and polymorphic sites were identified (Fig. 2). The haplotypes of heterozygotes were clarified by T-A cloning (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China) followed by clone sequencing (TSINGKE Biotech, Beijing, China). Network v.5.0 was used to analyze the evolutionary origin of An. sinensis vgsc haplotypes [27].

Fig. 2.

The nucleotide region of An. sinensis vgsc gene addressed in this study. Dots indicate the polymorphic sites (PS) in the obtained sequences. The red dots represent sites leading to nonsynonymous mutations. The positions of PS in the 255 bp sequence are numbered below the dots. The nucleotides for each PS are given

Results

The distribution and frequency of ace-1 genotypes

The G119S allele was detected at frequencies ranging from 0.61 to 0.85 in the seven populations (Fig. 1). The three possible individual genotypes were observed, and all genotypes were detected to agree with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (Table 1). Notably, the susceptible homozygotes (119GG) were rare: no susceptible homozygote was detected at DXEC, LZSK and FCGDX, and the frequencies of 119GG were less than 0.10 at the other four sites (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of Ace-1 genotypes in seven An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border

| Site | n | Frequency | Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test (P-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | GS | SS | Probability test | Heterozygote excess | Heterozygote deficiency | ||

| NPPM | 28 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 0.634 | 0.361 | 0.923 |

| JXXW | 23 | 2 | 14 | 7 | 0.377 | 0.212 | 0.957 |

| JXTD | 26 | 1 | 15 | 10 | 0.197 | 0.148 | 0.980 |

| DXEC | 31 | 0 | 11 | 20 | 0.553 | 0.342 | 1.000 |

| LZSK | 29 | 0 | 9 | 20 | 1.000 | 0.479 | 1.000 |

| PXSS | 32 | 2 | 19 | 11 | 0.148 | 0.119 | 0.978 |

| FCGDX | 33 | 0 | 14 | 19 | 0.300 | 0.175 | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: NPPM Pingmeng, Napo County, JXXW Xinwei, Jingxi County, JXTD Tongde, Jingxi County, DXEC Encheng, Daxin County, LZSK Shuikou, Longzhou County, PXSS Shangshi, Pingxiang County, FCGDX Dongxing town, Fangchenggang City

Sequence polymorphisms of An. sinensis vgsc gene

Thirteen nucleotide polymorphic sites (PS) were identified from the 255 bp DNA fragments individually amplified from a total of 208 mosquitoes (Fig. 2). The 1st to 3rd PSs were located on exon 19, the 4th to 11th PSs on intron 19, and the 12th and 13th PSs on exon 20. The polymorphisms in 2nd and 3rd PSs resulted in amino acid substitutions (L/F/S) at codon 1014, and the nucleotide variations in 1st, 12th and 13th PSs represented synonymous mutations (Fig. 2).

The distribution and frequency of kdr genotypes

Three kdr genotypes (1014LL, 1014LF and 1014LS) were identified from the samples (Table 2). The frequencies of the susceptible homozygotes (1014LL) ranged from 0.79 (FCGDX) to 1.00 (JXXW). The resistant heterozygote 1014LS was detected at six sites at frequencies ranging from 0.07 to 0.16, while the other resistant heterozygote 1014LF was found only at FCGDX at a frequency of 0.06 (Fig. 1). No significant deviation from HWE for the 1014 genotypes was observed in all the seven populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of kdr genotypes in seven An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border

| Site | n | Frequency | Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test (P-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | LF | LS | Probability test | Heterozygote excess | Heterozygote deficiency | ||

| NPPM | 28 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 1.000 | 0.947 | 1.000 |

| JXXW | 26 | 26 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| JXTD | 27 | 25 | 0 | 2 | 1.000 | 0.981 | 1.000 |

| DXEC | 31 | 28 | 0 | 3 | 1.000 | 0.952 | 1.000 |

| LZSK | 31 | 26 | 0 | 5 | 1.000 | 0.839 | 1.000 |

| PXSS | 32 | 29 | 0 | 3 | 1.000 | 0.949 | 1.000 |

| FCGDX | 33 | 26 | 2 | 5 | 1.000 | 0.708 | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: NPPM Pingmeng, Napo County, JXXW Xinwei, Jingxi County, JXTD Tongde, Jingxi County, DXEC Encheng, Daxin County, LZSK Shuikou, Longzhou County, PXSS Shangshi, Pingxiang County, FCGDX Dongxing town, Fangchenggang City

Diversity and frequency of kdr haplotypes

Eighteen kdr haplotypes were identified from the 208 An. sinensis individuals (Table 3). Among them, six haplotypes (i.e. 1014L15, 1014L16, 1014L17, 1014L18, 1014S5 and 1014S6) were new records.

Table 3.

kdr haplotypes and their frequencies in seven An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border

| Haplotype | Polymorphic sites | GenBank ID | Frequency | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPPM | JXXW | JXTD | DXEC | LZSK | PXSS | FCGDX | |||

| 1014L1 | CTGACGCTGCTCC | KY014584.1 | 0.214 | 0.173 | 0.333 | 0.274 | 0.194 | 0.156 | 0.273 |

| 1014L2 | CTGACGCCGCCTC | KY014585.1 | 0.482 | 0.519 | 0.389 | 0.435 | 0.210 | 0.313 | 0.242 |

| 1014L3 | CTGACTCCGCCTC | KY014586.1 | 0.089 | 0.192 | 0.111 | 0.081 | 0.355 | 0.250 | 0.061 |

| 1014L4 | CTGACTCTGCCTC | KY014587.1 | 0.018 | 0.048 | 0.016 | 0.063 | 0.045 | ||

| 1014L5 | GTGACGCCGCCTC | KY014588.1 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.032 | 0.078 | 0.015 | |

| 1014L6 | CTGTCGCCGCCTC | KY014589.1 | 0.036 | 0.058 | 0.037 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.076 |

| 1014L7 | CTGACGCTGCCCC | KY014590.1 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | ||||

| 1014L8 | CTGATGCCGCCTC | KY014591.1 | 0.054 | 0.019 | 0.037 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.152 |

| 1014L10 | CTGACGCTGCCTC | KP763768.1 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.016 | ||||

| 1014L15a | CTGACGCTGATCC | This study | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.015 | ||

| 1014L16a | CTGACTTCGCCTC | This study | 0.019 | 0.016 | |||||

| 1014L17a | TTGACGCTGCCCT | This study | 0.015 | ||||||

| 1014L18a | CTGACGCCTCCTC | This study | 0.018 | ||||||

| 1014F1 | CTTACGCTGCTCC | KY014598.1 | 0.030 | ||||||

| 1014S2 | CCGACGCCGCCTC | KY014594.1 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 0.032 | 0.081 | 0.047 | 0.045 | |

| 1014S3 | CCGACTCCGCCTC | KY014595.1 | 0.018 | 0.016 | |||||

| 1014S5a | CCGACGCTGCTCC | This study | 0.015 | ||||||

| 1014S6a | CCGTCGCCGCCTC | This study | 0.015 | ||||||

Haplotypes with a GenBank number were previously described in Yang et al. [20]

aNewly identified haplotypes

The geographical distribution of kdr haplotypes was varied in the An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border (Table 3). Seven (JXXW) to 13 (FCGDG) haplotypes were detected within these populations. Of the 13 susceptible haplotypes, 1014L1, 1014L2, 1014L3, 1014L6 and 1014L8 were widely distributed at the seven sites, and 1014L1, 1014L2 and 1014L3 represented the most prevalent haplotypes. Interestingly, the newly identified susceptible haplotypes, 1014L17 and 1014L18, were uniquely distributed at FCGDX and NPPM, respectively, at a low frequency (0.02).

Four 1014S (1014S2, 1014S3, 1014S5 and 1014S6) haplotypes were identified in this study (Table 3). The haplotype 1014S2 had higher frequencies and was more widely distributed than other 1014S haplotypes. The two newly identified 1014S haplotypes (1014S5 and 1014S6) and 1014F1 were only detected at FCGDX.

Evolutionary origin of 1014S haplotypes

Network analysis showed that 1014S2, 1014S3 and 1014S6 were derived from 1014L2, 1014L3 and 1014L6, respectively, while both 1014S5 and 1014F1 evolved from 1014L1 through only one mutational step (Fig. 3). Notably, both 1014F1 and 1014S5 were detected only at FCGDX (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

The network of kdr haplotypes identified in An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border. White solid, black and grey circles represent 1014L, 1014F and 1014S haplotypes, respectively. The size of each circle is proportional to its corresponding frequencies. The number in brackets represents intron type

Discussion

For all seven field populations of An. sinensis collected in Guangxi along the China-Vietnam border, the frequencies of the resistant 119S allele were high. This result supports the published literature indicating that the G119S mutation is widely distributed in Guangxi [12]. The high frequency of the 119S allele indicates a strong risk of resistance to OP and CM in these regions (unfortunately no OP or CM bioassay data are available to test this indication). Historically, OPs have been used for pest control in China since 1950s and, as such, the high occurrence of the G119S may be a consequence of the long-term use of OP in agriculture. The observations that all ace-1 genotypes did not deviate from HWE (Table 1) and that the resistant allele was present at a high frequency within the seven populations imply that mosquitoes carrying the G119S mutation may suffer no fitness cost under current natural conditions, or the cost mediated by G119S substitution may possibly be offset by unknown fitness modifiers.

Two different kdr mutations (1014S and 1014F) were identified in this study (Table 2, Fig. 1). These insecticide resistance-associated mutations occurred in heterozygous forms and at very low frequencies in these areas. Interestingly, the 1014C mutation, which is widespread and present at relatively high frequencies in northeast Guangxi [20], was not detected in this survey. In addition, 1014F1, which is widely distributed in several provinces of China including Guangxi [20], was detected only at FCGDX. By contrast, the 1014S allele was widely distributed along the border. The distinct distribution of the 1014S allele is likely a consequence of independent mutational events in different geographical locations. The distribution pattern observed in this study is consistent with previous observations showing that the frequency of kdr mutations decreases towards south and west from northeast [18–20, 28–30].

The present study demonstrates the geographical heterogeneities of kdr haplotypes and the presence of location-specific haplotypes (Table 3). For example, the haplotypes 1014S5 and 1014S6 were only detected in FCGDX. Furthermore, the genealogical analysis of vgsc haplotypes suggests that the 1014S2, 1014S3 and 1014S6 may have evolved from 1014L2, 1014L3 and 1014L6, respectively, adding support to the hypothesis that kdr mutations do not have a single origin [20]. Multiple origins of kdr mutations have also been documented in several other insect species [31, 32].

In the remote villages studied, no regular vector control programme has been implemented. The lack of pyrethroid selection pressure on the mosquito populations may explain why all vgsc alleles exhibit HWE, and why kdr is rare (Table 2). A recent preliminary survey indicated no loss of susceptibility to deltamethrin in An. sinensis adults collected from sampling sites same as in this study (conducted in June to August 2018 using the contact bioassay protocol recommended by China CDC, Dr. Fengxia Meng; personal communications). Based on the findings in this study, we suggest that pyrethroids remain suitable for use against An. sinensis. Noting that a strong insecticide resistance management programme should be implemented to maintain the susceptibility of vgsc alleles, it is recommended that the application of pyrethroids should not be taken as the sole measure for vector control and should be used in rotation or alongside insecticides with alternative modes of action.

Conclusions

High frequencies (0.61–0.85) of the G119S mutation in AChE and low frequencies of kdr mutations (0.00–0.11) were detected in An. sinensis populations along the China-Vietnam border. 1014S was the most common kdr mutation in these areas. Network analysis revealed that the 1014S mutation did not have a single origin. The data suggest that the vector control authorities should be cautious when considering carbamates and organophosphates as control agents. Instead, pyrethroids are suitable for An. sinensis control in these regions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would thank Ms Hui Yan (Guangxi CDC) for help in collecting samples. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their excellent comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant 2017ZX10303404002004. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets are presented in this published article. Representative sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers MH384262-MH384267.

Abbreviations

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- CM

Carbamate insecticides

- Guangxi

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- kdr

Knockdown resistance

- OC

Organochlorine insecticides

- OP

Organophosphorus insecticides

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PY

Pyrethroid insecticides

- RFLP

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

- VGSC

Voltage-gated sodium channel

Authors’ contributions

XHQ and XYF conceived the study. CY and NL performed the experiment. CY, NL and XHQ analyzed the data. XHQ, CY and XYF wrote the paper. XYF and ML contributed to sample collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chan Yang, Email: yangchan@ioz.ac.cn.

Xiangyang Feng, Email: 13077712341@163.com.

Nian Liu, Email: nianliu95@163.com.

Mei Li, Email: limei@ioz.ac.cn.

Xinghui Qiu, Email: qiuxh@ioz.ac.cn.

References

- 1.WHO . World Malaria Report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldlust SM, Thuan PD, Giang DDH, Thang ND, Thwaites GE, Farrar J, et al. The decline of malaria in Vietnam, 1991–2014. Malar J. 2018;17:226. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2372-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li JH, Li J, Qin YX, Guo CK, Huang YM, Lin Z, et al. Appraisal of the effect and measures on control malaria for 60 years in Guangxi. J Trop Med. 2014;14:361–364. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajgar J. Organophosphates/nerve agent poisoning: mechanism of action, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment. Adv Clin Chem. 2004;38:151–216. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2423(04)38006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuto TR. Mechanism of action of organophosphorous and carbamate insecticides. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;87:245–254. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9087245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Chen C, Zhao X, Wang Q, Qian Y. Assessing joint toxicity of four organophosphate and carbamate insecticides in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) using acetylcholinesterase activity as an endpoint. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2015;122:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Newcomb R, Forbes E, McKenzie J, Batterham P. The acetylcholinesterase gene and organophosphorus resistance in the Australian sheep blowfly, Lucilia cuprina. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;31:805–816. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong SL, Andrews MC, Li F, Moores GD, Han ZJ, Williamson MS. Acetylcholinesterase genes and insecticide resistance in aphids. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157:373–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khajehali J, Van Leeuwen T, Grispou M, Morou E, Alout H, Weill M, et al. Acetylcholinesterase point mutations in European strains of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) resistant to organophosphates. Pest Manag Sci. 2010;66:220–228. doi: 10.1002/ps.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li CX, Dong YD, Song FL, Zhang XL, Zhao TY. An amino acid substitution on the acetylcholinesterase in the field strains of house mosquito, Culex pipiens pallens (Diptera: Culicidae) in China. Entomol News. 2009;120:464–475. doi: 10.3157/021.120.0502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung IH, Kang S, Kim YR, Kim JH, Jung JW, Lee S, et al. Development of a low-density DNA microarray for diagnosis of target-site mutations of pyrethroid and organophosphate resistance mutations in the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Pest Manag Sci. 2011;67:1541–1548. doi: 10.1002/ps.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng X, Yang C, Yang Y, Li J, Lin K, Li M, et al. Distribution and frequency of G119S mutation in ace-1 gene within Anopheles sinensis populations from Guangxi, China. Malar J. 2015;14:470–474. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-1000-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek JH, Kim HW, Lee WJ, Lee SH. Frequency detection of organophosphate resistance allele in Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae) populations by real-time PCR amplification of specific allele (rtPASA) J Asia Pac Entomol. 2006;9:375–380. doi: 10.1016/S1226-8615(08)60317-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong K. Insect sodium channels and insecticide resistance. Invertebr Neurosci. 2007;7:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s10158-006-0036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong K, Du YZ, Rinkevich F, Nomura Y, Xu P, Wang LX, et al. Molecular biology of insect sodium channels and pyrethroid resistance. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;50:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva APB, Santos JMM, Martins AJ. Mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of anophelines and their association with resistance to pyrethroids - a review. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:450. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinkevich FD, Du YZ, Dong K. Diversity and convergence of sodium channel mutations involved in resistance to pyrethroids. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2013;106:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang X, Zhong D, Lo E, Fang Q, Bonizzoni M, Wang X, et al. Landscape genetic structure and evolutionary genetics of insecticide resistance gene mutations in Anopheles sinensis. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:228. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1513-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Yu W, Shi H, Yang Z, Xu J, Ma Y. Historical survey of the kdr mutations in the populations of Anopheles sinensis in China in 1996–2014. Malar J. 2015;14:120–129. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0644-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang C, Feng X, Huang Z, Li M, Qiu X. Diversity and frequency of kdr mutations within Anopheles sinensis populations from Guangxi, China. Malar J. 2016;15:411–418. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1467-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhaeghen K, Van Bortel W, Ho DT, Sochantha T, Keokenchanh K, Coosemans M. Knockdown resistance in Anopheles vagus, An. sinensis, An. paraliae and An. peditaeniatus populations of the Mekong region. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:59. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu B, Wu H. Classification and identification of important medical insects of China. 1. Zheng Zhou: Henan Science and Technology Publishing House; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinkevich FD, Zhang L, Hamm RL, Brady SG, Lazzaro BP, Scott JG. Frequencies of the pyrethroid resistance alleles of Vssc1 and CYP6D1 in house flies from the eastern United States. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:157–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raymond M, Rousset F. GENEPOP (version 1.2): Population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Hered. 1995;86:248–249. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rousset F. GENEPOP '007: a complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhong D, Chang X, Zhou G, He Z, Fu F, Yan Z, et al. Relationship between knockdown resistance, metabolic detoxification and organismal resistance to pyrethroids in Anopheles sinensis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin Q, Li YJ, Zhong DB, Zhou N, Chang XL, Li C, et al. Insecticide resistance of Anopheles sinensis and An. vagus in Hainan Island, a malaria-endemic area of China. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang XL, Zhong DB, Fang Q, Hartsel J, Zhou GF, Shi LN, et al. Multiple resistances and complex mechanisms of Anopheles sinensis mosquito: a major obstacle to mosquito-borne diseases control and elimination in China. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anstead JA, Williamson MS, Denholm I. Evidence for multiple origins of identical insecticide resistance mutations in the aphid Myzus persicae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rinkevich FD, Hedtke SM, Leichter CA, Harris SA, Su C, Brady SG, et al. Multiple origins of kdr-type resistance in the house fly, Musca domestica. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets are presented in this published article. Representative sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers MH384262-MH384267.