Second generation Latina adolescents experience increases in severity while immigrant Latinas experience decreases in severity for a syndemic comprised of substance use, intimate partner violence and depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Keywords: Substance use, Intimate partner violence, Depression, Health disparities, Adolescents

Abstract

Background

Syndemics are co-occurring epidemics that synergistically contribute to specific risks or health outcomes. Although there is substantial evidence demonstrating their existence, little is known about their change over time in adolescents.

Purpose

The objectives of this paper were to identify longitudinal changes in a syndemic of substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression and determine whether immigration/cultural factors moderate this syndemic over time.

Methods

In a cohort of 772 pregnant Latina adolescents (ages 14–21) in New York City, we examined substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression as a syndemic. We used longitudinal mixed-effect modeling to evaluate whether higher syndemic score predicted higher syndemic severity, from pregnancy through 1 year postpartum. Interaction terms were used to determine whether immigrant generation and separated orientation were significant moderators of change over time.

Results

We found a significant increasing linear effect for syndemic severity over time (β = 0.0413, P = 0.005). Syndemic score significantly predicted syndemic severity (β = –0.1390, P ≤ 0.0001), as did immigrant generation (βImmigrant = –0.1348, P ≤ 0.0001; β1stGen = –0.1932, P = 0.0005). Both immigrant generation (βImmigrant = –0.1125, P = 0.0035; β1stGen = –0.0135, P = 0.7279) and separated orientation (β = 0.0946, P = 0.0299) were significantly associated with change in severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum.

Conclusion

Pregnancy provides an opportunity for reducing syndemic risk among Latina adolescents. Future research should explore syndemic changes over time, particularly among high-risk adolescents. Prevention should target syndemic risk reduction in the postpartum period to ensure that risk factors do not increase after pregnancy.

Introduction

Risk behaviors are higher among adolescents and young adults, impacting numerous health outcomes [1,2]. The younger an individual is when becoming burdened by poor health, the greater the potential for disability, lower quality of life, and years of life lost [3–5]. Such risk factors and disease burdens subsequently feed health disparities in the population, exacerbating health inequalities among vulnerable groups and making disparities much more intractable.

Young Latina women and adolescents are at particular risk for adverse health outcomes, often perpetuated by structural and environmental factors that exacerbate inequalities. For example, research with Latina populations has shown substantial disparities in sexually transmitted infections, teenage pregnancy, and other health effects, many of which have a long-term impact on quality of life and health [6, 7]. Understanding cultural factors that may be driving differences in health disparities within Latina populations is an important area of study.

For example, pregnant adolescents may be a particularly vulnerable sub-group. Pregnancy in adolescence is associated with reports of unprotected sex, raising additional risks associated with sexually transmitted infections and HIV among pregnant youth. Additionally, pregnancy and early parenthood is a time of transition and increased stress that could make Latina adolescents susceptible to other risks [8]. Depression, substance use, and partner violence may be factors affecting adolescent mothers during this new transition period. More research is needed to understand if psychosocial and behavioral risks (e.g., depression, intimate partner violence, and substance use) increase or change over the pregnancy to parenthood transition. And, if so, whether pregnancy provides a window of opportunity for prevention for these young women and their families.

Syndemics

Although there are several factors known to impact pregnant, Latina adolescents, one particular type of risk are syndemics where risk factors cluster or co-occur. These clusters lead to an aggregate level of risk in the population, which is greater than the risk caused by any individual factor [9, 10]. Although many groups report the same risk factors, groups impacted by syndemics experience a risk profile that is much greater than that seen in other populations [9, 10]. Syndemics often overburden highly vulnerable groups like racial/ethnic minorities and women [10–13]. Latina women have been particularly affected by syndemics [14–16]. Latina adolescents have increased burden of depression [17, 18], intimate partner violence [19, 20], and substance use [21–23] which have been linked to numerous negative health behaviors and outcomes [24–26]. Recent studies have shown that these risk factors form a syndemic for Latina adolescents [12, 27] and pregnant Latina adolescents. Although there is substantial evidence documenting the impact and burden of syndemics on Latina women’s health, relatively little is known regarding their development over time. Specifically, no studies have evaluated when they first manifest or how they change during a time of stress and transition (e.g., adolescent pregnancy).

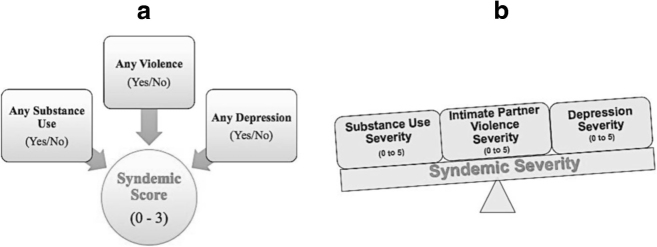

Our previous research has expanded the concept of syndemics to explore two facets of syndemics and their impact on participants of a bundled HIV and prenatal care intervention study: syndemic score and severity (see Fig. 1) [12, 27]. Syndemic score is defined as the number of factors (substance use—including smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, hard drug use and injection drug use; intimate partner violence victimization; and depression) an individual reports experiencing (e.g., 0, 1,2, or 3 syndemic factors present). Syndemic score does not take into account the intensity or severity of any of the syndemic factors, but rather functions as a tally or count of the number of factors. Previous studies on syndemics have utilized this measure to evaluate syndemic risk [11, 28]. Syndemic severity is a new measure developed to represent the overall level/intensity of syndemic factors. Severity provides an average level of syndemic factors reported. For example, individuals who report high levels of depression, intimate partner violence victimization, and substance use behaviors will have higher severity scores than individuals with moderate levels of depression, intimate partner violence, and substance use behaviors. As compared to syndemic score, syndemic severity would differ by these high and low levels, whereas syndemic score would be the same because the number of behaviors reported is the same.

Fig. 1.

Syndemic score (a number of behaviors reported) and syndemic severity (b average degree of behaviors reported)

Previous research found that syndemic severity was more predictive of future risk behavior than syndemic score, suggesting the importance of understanding how syndemic severity and the factors that may relate to syndemic severity over time [27]. Further, limited research has explored how syndemic score and severity interact, and how syndemic score may relate to changes in syndemic severity over time.

Adolescence may provide an opportune time for reducing and preventing syndemics at their inception, rather than targeting them later in life. Particularly among pregnant adolescents participating in an intervention study to reduce their HIV risk during pregnancy, understanding how syndemics change longitudinally can not only inform prevention efforts but may also serve as an opportunity to reduce syndemic risk alongside HIV risk reduction. This period from pregnancy through postpartum may be an ideal time to target high-risk Latina adolescents, while understanding how syndemics change over time.

The Role of Immigration and Culture in Syndemics

There are certain structural factors that may be relevant to or more likely to affect phenomena like syndemics among pregnant Latina adolescents. Immigrant generation, for instance, tells us whether an individual was born in another country (immigrant), whether they were born in the USA and their parents were foreign born (first generation), or whether both that individual and their parents are US born (second generation). Certain cultural variations and practices may differ between immigrant and first-generation individuals, as well as immigrant and first-generation parents. Also particularly relevant among Latinas are aspects of acculturation, like separated orientation which indicates an individual’s orientation to a foreign culture. Acculturation is used to measure various practices, habits, and customs of an individual. If an individual is oriented to a foreign country rather than the USA, this indicates different culture, practices, and possibly norms that guide that individual’s behaviors [29].

In a previous study of syndemics, both immigrant generation and acculturation moderated syndemic risk factors in pregnant Latina adolescents participating in an HIV cluster randomized trial for HIV prevention [27]. Complex in their effects, we found immigrants to have higher risk for multiple sex partners with higher severity. We also found conflicting effects for condom use, with higher severity leading to more condom use among immigrants but less condom use among individuals with a separated orientation. There may be change between cohorts of immigrants and later generations for syndemics that must be identified and explored to better understand such variations in the population. Evaluating immigrant generation and separated orientation longitudinally may inform how changes occur over time, helping us to better understand these moderated associations. Understanding how risk varies by cultural traits might help us to understand the extent of the burden in this population and target prevention efforts. Focusing on our objectives of (1) identify longitudinal changes in syndemic severity over time and (2) determining whether immigration/cultural factors moderate syndemic change, the current study had three aims:

-

Describe the trajectory of syndemic severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum among Latina adolescents.

Hypotheses 1: Syndemic severity will increase from pregnancy to postpartum time period, much like individual risk factors of substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression [20, 30–32].

-

Assess whether syndemic score predicts syndemic severity and changes in syndemic severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum.

Hypothesis 2a: Higher syndemic scores would be associated with higher syndemic severity (syndemic score main effect).

Hypothesis 2b: Higher syndemic scores would be associated with more change in syndemic severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum (syndemic score × time interaction).

-

Determine whether acculturation (immigration generation and separated orientation) predicts syndemic severity and changes in syndemic severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum.

Hypothesis 3a: First- and second-generation women would have higher syndemic severity than immigrant women (immigrant generation main effect).

Hypothesis 3b: First- and second-generation women would have more change in syndemic severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum than immigrant women (immigrant generation × time interaction).

Hypothesis 3c: Women with a separated orientation would have higher syndemic severity than women with a non-separated orientation (separated orientation main effect). We base this hypothesis on structural barriers that may arise for individuals with low acculturation to the USA (e.g., language barriers), and also are associated with reduced health care access and poor health [33, 34]. Hypothesis 3d: Women with a separated orientation would have more change in syndemic severity from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum than women with a non-separated orientation (separated orientation × time interaction).

Methods

Using data from the Centering Pregnancy Plus (CP+) study, a subset of 772 Latina participants were selected for these analyses. The sub-sample was comprised of all participants in the CP+ study who self-identified as Latina. This is a cluster randomized controlled trial at 14 community hospitals and health centers in New York City [8, 35]. The original study was designed to evaluate perinatal and reproductive health impacts of an innovative model of group prenatal care [36]. Participants were interviewed at four time points across the perinatal period: second and third trimesters of pregnancy as well as 6 and 12 months postpartum.

Demographic information included age (14–21 years old), education (less than high school graduate, high school graduate, more than high school), income source (self, parents, partner, other), and relationship status (single, other). Intervention arm (intervention, control) was controlled in all analyses.

Syndemic Measures

Risk factors included substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression. All behaviors were measured during baseline (around 16-week gestation), third trimester of pregnancy (around 32-week gestation), 6 months postpartum, and 1 year postpartum. For baseline measures, these included reported risk factors in the previous 12 months and since pregnant. These variables were coded to create our two syndemic measures (Fig. 1). The first, syndemic score, is a measure of the number of reported behaviors (range = 0 to 3). To create this variable, we created a dichotomous measure for each individual behavior (yes/no; substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression) that was summed to measure the number of experiences each participant reported.

Syndemic severity measured the severity of each risk behavior (substance use, intimate partner violence, depression) ranging from 0 to 5. For substance use, severity accounted for the number of substance use behaviors reported by the participant: tobacco, alcohol use, marijuana use, injection drug use (reported injecting drugs), and/or hard drug use (crack, cocaine, heroin, and other hard drugs—not injected). For violence, victimization responses from the Conflicts and Tactic Scale were used to measure level of experienced violence [37]. Individuals not experiencing any victimization received a severity score of 0. Severity was operationalized using quintiles of responses from among study participants (range = 1 to 5). Clinical guidelines were used to identify individuals experiencing depression using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [38]. Individuals reporting no depressive symptoms received a depression severity score of 0. Individuals receiving scores lower than 12 were either categorized as have little to no depressive symptoms or experiencing pre-depression symptoms following the CES-D classifications [38]. Individuals with scores greater than or equal to 12 were divided into tertiles for severity of depressive symptoms. Combining these categories, individuals could receive a severity level of 1 to 5 for depression.

An overall syndemic severity was calculated by summing severities across the three individual factors—substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression—and dividing by syndemic score. Thus, a participant’s syndemic severity is the average score across all syndemic factors reported.

Analyses

To address Aim 1, we examined time trends predicting syndemic severity from pregnancy to postpartum (across all four time points). We used PROC MIXED to model severity across time. To address Aim 2, we used syndemic score (range 0–3) to model severity across time. We evaluated bivariate and multivariate associations to determine whether score predicted severity (Aim 2a) and used interactions to identify significant change over time (Aim 2b). A significance value of P ≤ 0.05 was used to determine both the appropriate effect of time and significant covariates to include in the full model. For Aim 3, we used both immigrant generation (immigrant, first generation, second generation) and separated orientation (separated, not separated) to predict syndemic severity. For Aim 3 a, we included immigrant generation as a primary predictor of syndemic severity (range 0–5) along with syndemic score. We tested bivariate and multivariate associations to see if immigrant generation predicted syndemic score (Aim 3a). We also tested interaction terms for immigrant generation × time to identify differences by generation across time (Aim 3b). For Aim 3c, we evaluated separated orientation as a primary predictor of severity in bivariate and multivariate models. We also tested the interaction between separated orientation × time to determine whether or not differences in severity change exist over time (Aim 3d). Individual time points were also evaluated to compare treatment arms for any significant difference throughout the study. We also compared participants who completed the study with those who dropped out. There were no significant differences by treatment arm at any time point, and no significant difference between participants retained compared to those who dropped out of the study (n = 115; 14.9%) or missed a follow-up interview. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 statistical analysis software.

Results

Syndemic and demographic information for this sample is provided in Table 1. Overall, 20.1% of participants reported engaging in all three syndemic factors. There were no significant differences in age, income, relationship status, or treatment arm in the sample and only 115 (14.9%) of participants dropped out of the study. A total of 0.26% at time 1, 25.5% at time 2, 44.3% at time 3, and 33.7% at time 4 were missing. However, most participants participated in two or more assessments. T tests were used to compare those who participated at each interview with those who did not, as well as those who dropped out of the study with those who remained. There were no significant differences between groups. Intervention arm was further evaluated at each time, with no significant differences in syndemic severity at any time point between intervention and control groups. All participants, regardless of missing an interview, were included in the study. Differences in education by syndemic score were found, with a majority of individuals reporting a score of 3 not having graduated from high school (67.7%). The mean syndemic severity for the entire cohort was 1.66 (SD = 0.73). Mean severity also increased by level of syndemic score in the sample indicating that as a participant reported more than one syndemic factor (substance use, intimate partner violence, depression), the average level or intensity of those factors also increased (e.g., more substance use, violence, depression reported).

Table 1.

Demographics stratified by syndemic score (N = 772)

| Number of syndemic factorsa | Score = 0 (n = 165), 21.4% | Score = 1 (n = 237), 30.7% | Score = 2 (n = 215), 27.9% | Score = 3 (n = 155), 20.1% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 18.47(1.75) | 18.47(1.73) | 18.68(1.85) | 18.68 (1.85) | P = 0.4832 |

| Education (n, %) | P = 0.0255 | ||||

| Less than high school | 118(73.8%) | 156(66.1%) | 121 (56.5%) | 105 (67.7%) | |

| High school graduate | 21 (13.1%) | 44 (18.6%) | 44 (20.6%) | 28(18.1%) | |

| Some college or more | 21 (13.1%) | 36 (15.3%) | 49 (22.9%) | 22 (14.2%) | |

| Relationship status (n, %) | P = 0.3542 | ||||

| Single | 68 (63.8%) | 114(57.6%) | 99 (54.7%) | 90 (63.8%) | |

| Other | 51 (36.2%) | 84 (42.4%) | 82 (45.3%) | 51 (36.2%) | |

| Income source (n, %) | P = 0.1053 | ||||

| Self | 25 (15.2%) | 41 (17.3%) | 39(18.1%) | 24 (15.5%) | |

| Partner | 69(42.1%) | 90 (38.0%) | 79 (36.7%) | 44 (28.4%) | |

| Parents | 56 (34.2%) | 80 (33.8%) | 64 (29.8%) | 58 (37.4%) | |

| Other | 14 (8.6%) | 26(11.0%) | 33(15.4%) | 29 (18.7%) | |

| Study condition (n, %) | P = 0.4071 | ||||

| Control | 73 (44.2%) | 124 (52.3%) | 109 (50.7%) | 80 (51.6%) | |

| Intervention | 92 (55.8%) | 113 (47.7%) | 106 (49.36%) | 75 (48.4%) | |

| Syndemic severity, range 1—5 (mean, SD) | n/a | 1.49(0.82) | 1.67 (0.67) | 1.88(0.60) | P≤ 0.0001 |

Presence of syndemic factors: substance use, intimate partner violence, and/or depression

Aim 1: Changes in Syndemic Severity over Time

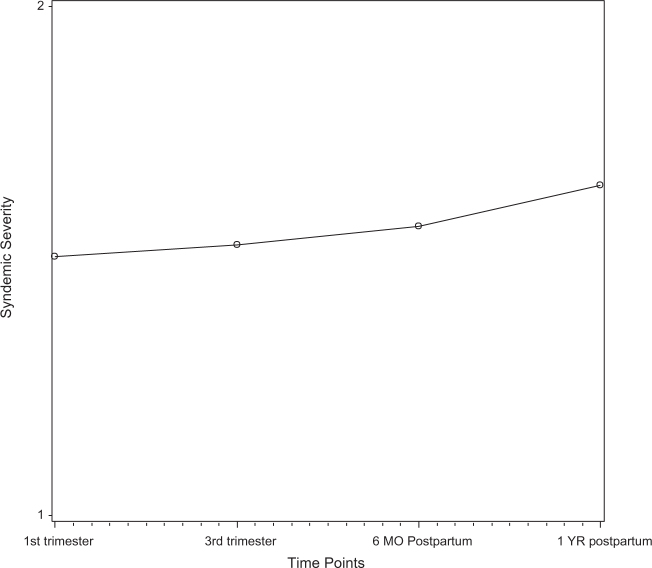

To test whether syndemic severity changed longitudinally among pregnant Latina adolescents (Aim 1), we evaluated the effect of time. We first tested for cubic effect (β = –0.8159, P = 0.8159) and then quadratic effect (β = –0.0201, P = 0.208), but both were not significant in predicting syndemic severity. We then tested and found a linear effect for time predicting syndemic severity (β = 0.0413, P = 0.005), showing a slow but steady increase from pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. This confirmed our first hypothesis. Figure 2 shows the overall change in syndemic severity over time.

Fig. 2.

Overall syndemic severity across time

We tested all individual covariates in bivariate analyses to determine which should be included in final models (P < 0.05). Keeping time as a random effect, only education was significantly associated with syndemic severity over time (β<HS Grad = 0.2701, P ≤ 0.001; β = HSGrad = 0.1030, P = 0.051). Treatment arm (β = 0.0672, P = 0.4124), participant’s age (β = –0.0363, P = 0.104), income source (βself = –0.0966, P = 0.502; βpartner = –0.0244, P = 0.849; βparents = –0.2227, P = 0.076), and relationship status (β = 0.1075, P = 0.194) were not associated with syndemic severity.

Aim 2: Syndemic Score as a Predictor of Severity Across Time

To test whether syndemic score predicted severity overall and across time (Aim 2) among these pregnant adolescents, we began by testing the effect of syndemic score (β = –0.1494, P = 0.0101) as a predictor of severity in bivariate analyses. Syndemic score was significantly and positively associated with syndemic severity across time. We then controlled for important covariates in multivariate analyses. This model included linear time as a random effect, education as a covariate (fixed effect), and syndemic score as the main predictors of syndemic severity across time (fixed effects). Syndemic score remained a significant predictor of syndemic severity in this full model (β = –0.1390, P ≤ 0.0001). There was no significant interaction between syndemic score and severity across time (βtime*score = –0.0015, P = 0.9402). Therefore, hypothesis 2b was not confirmed.

Aim 3: Immigrant Generation and Acculturation as Moderators of Severity

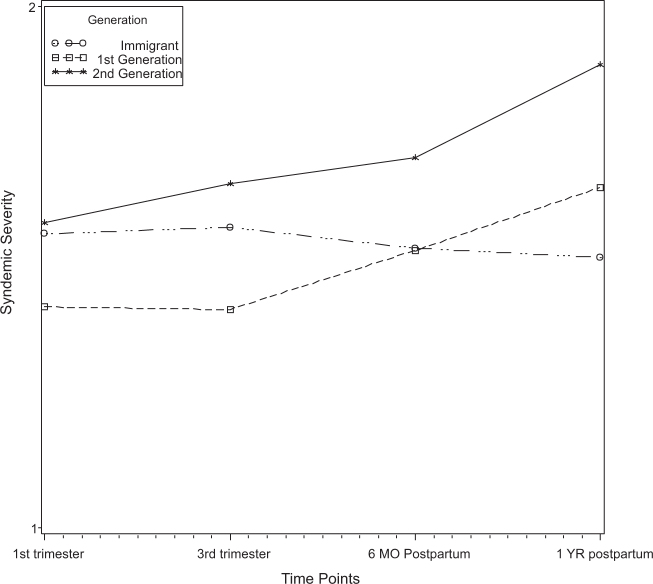

Next, we sought to evaluate two potential moderators of this association: immigrant generation and separated orientation, a measure of acculturation (Aim 3). We did not find a significant effect for immigrant generation in bivariate analyses (βimmigrant = –0.1396, P = 0.2056; β1stGen = –0.1702, P = 0.1237). However, in the full model including the effect of time, syndemic score, and covariates, immigrant generation was significantly associated with syndemic severity (βimmigrant = –0.1348, P ≤ 0.0001; β1stGen = –0.1932, P = 0.0005), indicating a protective effect for syndemic severity for immigrants and first-generation individuals compared to second-generation individuals. In other words, second-generation individuals have a higher rate of syndemic severity than other generational groups, consistent with hypothesis 3a.

We then tested interactions for time and immigrant generation to determine whether immigrant generation moderated syndemic score across time. We found a significant interaction for immigrants, indicating differences by immigrant generation for change in syndemic severity across time (βtime*immigrant = –0.1125, P = 0.0035; β1stgen = –0.0135, P = 0.7279). There were significant differences in change in syndemic severity for immigrants compared to second-generation individuals, consistent with our hypothesis 3b (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Syndemic severity over time by immigrant generation

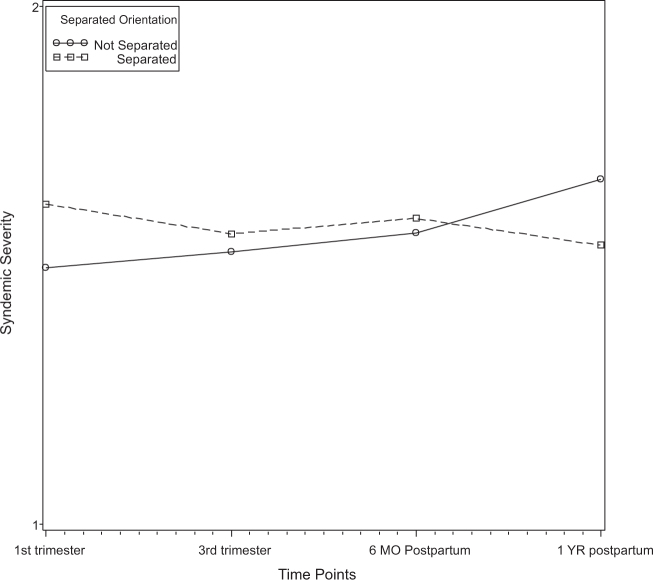

Next, we tested separated orientation as a predictor of syndemic severity (Aim 3c). Pregnant Latina adolescents with a separated orientation have higher syndemic severity than those who are not separated in bivariate analyses (β = –0.2513, P = 0.045). In multivariate analyses, the association was no longer significant (β = –0.0054, P = 0.9267), failing to support hypothesis 3c and indicating that no differences exist in syndemic severity by separated orientation.

Finally, we tested the interaction between separated orientation and time to determine whether separated orientation moderated change in syndemic severity over time (Aim 3d). We found a significant association for non-separated individuals confirming our hypothesis 3d (β = 0.0946, P = 0.0299). Syndemic severity significantly increased over time for women with non-separated orientation compared to women with separated orientation, contrary to hypothesis 3d (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Syndemic severity over time by separated orientation

Discussion

Overall, our study showed the impact of syndemic severity for Latina adolescents during an important time of transition: from pregnancy to becoming young parents. Results confirmed our hypotheses that syndemic severity increases from pregnancy through the postpartum period. This highlights the need for prevention services across the perinatal period, particularly with syndemic severity increasing during this time. The reduction in risk behaviors during pregnancy serves as an opportune time for targeting syndemics before their severity increases in the postpartum period. A reduction in syndemic risk factors could also serve to reduce sexual risk and HIV risk in the population. Risk behaviors may have an impact on parenting and child health outcomes, with substance use, violence, and depression impacting the health and well-being of both mothers and their infants. Given an increasing trend in “bundled” prevention services (i.e., integrated care), it may be useful to use the prenatal care period and postpartum visits to target syndemic reduction and prevent increase in syndemic risk factors from occurring [36].

Syndemic score was a significant predictor of severity. However, score was not associated with change over time. Contrary to our hypothesis, syndemic score was not associated with increased syndemic severity over time. Perhaps pregnancy impacts our ability to observe such increases over time, particularly if behavioral risks are reduced during and after pregnancy.

Future research should continue to evaluate changes in syndemic severity in the postpartum period, as well as outside of the pregnancy framework to understand trajectories of change in similar high-risk groups. Results highlight the need for concentrated prevention among adolescents experiencing multiple syndemic factors, particularly during pregnancy. Pregnancy may be a window for prevention of risk factors that increase in the postpartum period. Targeting such behaviors during pregnancy when risk is lower may help to support primary prevention efforts and reduce the risk of syndemic severity from increasing postpartum.

We found higher and increasing levels of syndemic severity among second-generation adolescents. This suggests that a particular focus is needed for those with a family history of immigration. This may highlight differences in social support, familism, and other resources reported in immigrant communities, which may not be available for second-generation women [39–41]. This may also be indicative of a Latina health paradox like we see for other reproductive/maternal health outcomes and even mortality [42–44]. If so, immigrant and less acculturated women may be at reduced risk because of cultural factors, a protective effect that dissipates as women become more acculturated and integrated into the USA.

This is supported by our evaluation of separated orientation, which indicates a decrease in syndemic severity over time among separated women and an increase in severity among non-separated women. This was contrary to our initial hypothesis that separated women would have higher severity compared to women who are not separated. Our findings also suggest that higher severity is seen among separated women compared to non-separated women at the beginning of pregnancy, which may be tied to other risk factors (e.g., sexual risk) in this group of women. Consistent with previous research, it may be the case that a Latina health paradox exists for syndemic risk, where better health is seen in immigrant populations despite facing higher risk. Regardless, non-separated (e.g., acculturated) Latina women should be targeted for their syndemic behaviors from both an individual and structural standpoint to prevent increases in syndemic severity from occurring after pregnancy.

Overall, we confirmed that differences exist by immigrant generation and separated orientation for syndemic severity. Given the generational cohort differences, it may be the case that intergenerational risk creates higher levels of burden for older generations (e.g., more risk is introduced between generations). Future research should explore intergenerational patterns of syndemic risk to determine whether this is the case. This also highlights the potential detrimental effect of acculturation often seen for sexual risk behaviors and reproductive health outcomes among Latina populations, although differences by separated orientation were not substantial [45, 46]. Future research should continue to explore cultural factors such as acculturation and generation to better understand how these syndemics develop longitudinally. Future research must also take into consideration the implications syndemics have for sexual risk and HIV risk. If factors like immigration and acculturation account for differences within Latina populations for syndemics, similar patterns could be occurring for HIV risk and sexual risk outcomes that could be utilized to improve and tailor programming in diverse communities. Differences in effect by immigrant generation and changes across time by separated orientation may serve as indicators of health paradoxes within syndemics and both sexual risk and HIV risk, which have been reported among immigrant and Latina populations for various health outcomes [47, 48].

Findings identify the opportunity to reduce risk by focusing on intergenerational prevention efforts (i.e., between parents and their adolescent children). Among second-generation women, we saw a steeper increase in syndemic severity indicating greater risk among this group. As such, first-generation immigrants may be a population to target to raise awareness on syndemics. Health education with parents can help raise awareness and emphasize the increased risk that their second-generation children may face. Finally, targeting parents is critically important given that teenage pregnancy often “repeats” in later generations. Targeting teen mothers may be an avenue for reducing syndemic burden given the risk associated with unintended pregnancies (e.g., unprotected sex). Exploring factors known to buffer risk in immigrant Latino communities (e.g., social support) may reduce burden and/or improve resiliency among older generations. Structural determinants should be integrated into prevention to help target syndemics from both an individual and structural level. Further exploration of structural determinants of health will be valuable for syndemic research, as these phenomena seem to be perpetuated by such factors. Other factors that explore resiliency must also be integrated for syndemic studies.

Overall, this study informs scientific knowledge regarding syndemics among Latina immigrant populations. Health professionals and clinicians serving high-risk Latinas should look to behaviors not yet reported to mitigate any development prior to its inception. It might be useful to develop “bundled” HIV prevention programs that incorporate substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression resources for Latina adolescents to prevent an increase in syndemic severity and help individuals only engaging in one or two risk factors navigate away safely from remaining syndemic factors. This could buffer adverse effects of syndemics in this population. Targeting pregnant adolescents, particularly those reporting all three risk factors, should be a public health priority to reduce burden and reduce intergenerational cycles of syndemic risk. Incorporating both parents and adolescents will address multiple avenues and may be more effective than traditional health education programs.

Limitations and Strengths

This study only included data from pregnant Latina adolescents. The high-risk nature of this population does help us identify trends in the population. However, additional research is needed to fully understand how non-pregnant adolescents are affected by this syndemic. Additionally, participants from this study were enrolled in an intervention trial to reduce HIV risk during pregnancy. Given the nature of their enrollment, this particular cohort of individuals may be proactive in obtaining and navigating health care services which may be associated with their syndemic risk. It is possible that a stronger syndemic effect exists for pregnant adolescents who have less access to health care and were not represented in this study. Second, the current study only included information on generation ranging from immigrant to second-generation groups. This category could be confounded by individuals with older family histories of immigration (e.g., third generation, fourth), who could experience syndemics in varying ways. Future research should continue exploring immigrant generation in the context of syndemics and include information beyond second generation to understand how third-generation adolescents and beyond differ from immigrants, first generations, and distinguish the effects of second-generation adolescents. Although we focused on substance use, intimate partner violence, and depression as a syndemic among Latina adolescents, other syndemics should be explored in adolescent populations (e.g., adult men who have sex with men vs adolescents). Finally, the current study was limited in that only two cultural variables were included in analyses. Future studies should explore additional cultural factors such as language, acculturation, and other important information to distinguish differences in syndemic effects and how other factors might serve to reduce risk. Importantly, understanding how these factors interact with the surrounding environment and social determinants of health (e.g., poverty, language barriers, citizenship) will be pertinent to a comprehensive understanding of the diversity of risk and resilience in Latina populations. Resiliency factors such as family support, community support, and culture should also be included and explored to identify how to simultaneously reduce risk and promote health within syndemic studies. Even so, this study does provide a unique outlook on the impact syndemics have in this population and across time.

Conclusions

This study provides a platform for informing syndemic research. Adopting this syndemic framework for adolescents enhances our understanding of the development of syndemics, and informs program development aimed at eliminating these high-burden, complex phenomena altogether. Bundled interventions that target all syndemic factors must be integrated into prevention, specifically with young pregnant adolescents and other high-risk groups to eliminate any detrimental effects and improve longevity and quality of life in these groups. Future research should continue to explore syndemics among young populations to identify how best to reduce these public health problems and provide services to address such phenomena in young, highly vulnerable populations.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Author’s Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

The research presented in this manuscript has not been previously published. This research is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30MH062294. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The data used in analyses were obtained from the Centering Pregnancy Plus study, which is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT00628771). Procedures for this study were approved by the human investigation committees at site (Yale #0408026962). The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30MH062294. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- HIV/AIDS surveillance in adolescents and young adults (through 2005). CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/ppt/statistics_surveillance_Adolescents.ppt. Published April 27, 2016. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- Costello E. J., Copeland W., & Angold A.Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: what changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults?. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011; 52(10): 1015–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey J. M., Chang J. J., & Kotch J. B.Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006; 118(3):933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T. E., Caspi A., Harrington H., & Milne B. J.Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol. 2002; 14(01):179–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K., Egeland B., Dulmen M. H., & Alan Sroufe L.When more is not better: the role of cumulative risk in child behaveior outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005; 46(3):235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnis A. M., Marchi K., Ralph L. et al. Limited socioeconomic opportunities and Latina teen childbearing: a qualitative study of family and structural factors affecting future expectations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013; 15(2): 334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doğan-Ateş A., & Carrión-Basham C. Y.Teenage pregnancy among Latinas examining risk and protective factors. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2007; 29(4):554–569. [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R., Reed E., Magriples U., Westdahl C., Schindler Rising S., & Kershaw T. S.Effects of group prenatal care on psychosocial risk in pregnancy: results from a randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health. 2011; 26(2):235–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inq Creat Sociol. 1996; 24(2):99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. C., Erickson P. I., Badiane L. et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med. 2006; 63(8):2010–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B., Garofalo R., Herrick A., & Donenberg G.Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007; 34(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illangasekare S. L., Burke J G., Chander G., & Gielen A. C.Depression and social support among women living with the substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS syndemic: a qualitative exploration. Women’s health issues. 2014; 24(5):551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. P., Springer S. A., & Altice F. L.Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt).2011; 20(7): 991–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT., Vasquez EP, Mitrani VB.. HIV risks, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic women and their intimate partners. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008; 19(4): 252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda R. M., McCabe B.E., Florom-Smith A., Cianelli R., and Peragallo N.. Substance abuse, violence, HIV, and depression: an underlying syndemic factor among Latinas. Nurs Res. 2011; 60(3): 182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda RM., Florom-Smith AL., Thomas T.. A syndemic model of substance abuse, intimate partner violence, HIV infection, and mental health among Hispanics. Public Health Nurs. 2011; 28(4): 366–378. Doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Céspedes YM, Huey SJ. Depression in Latino adolescents: a cultural discrepancy perspective. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008; 14(2):168–172. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarté-Vélez Y M., & Bernal G.Suicide behavior among Latino and Latina adolescents: conceptual and methodological issues. Death Stud. 2007; 31(5): 435–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman B. S., & Campbell C.Intimate partner violence among pregnant and parenting Latina adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 2011; 26(13): 2635–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M. A., Valentine J., Ahmed S. R. et al. Intimate partner violence and maternal depression during the perinatal period: a longitudinal investigation of Latinas. Violence Against Women. 2010; 16(5): 543–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C. R. Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Fam Relat. 2006; 55(3): 306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Peña J. B., Wyman P. A., Brown C. H. et al. Immigration generation status and its association with suicide attempts, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the USA. Prev Sci. 2008; 9(4):299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J B., Ritt-Olson A., Soto D. W., & Baezconde-Garbanati L.Parent—child acculturation discrepancies as a risk factor for sub stance use among Hispanic adolescents in Southern California. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009; 11(3):149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. L., Elliott M. N., Fuligni A. J., Morales L. S., Hambarsoomian K., & Schuster M. A.The relationship between Spanish language use and substance use behaviors among Latino youth: a social network approach. J Adolesc Health. 2008; 43(4):372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granillo T., Jones-Rodriguez G., & Carvajal S. C.Prevalence of eating disorders in Latina adolescents: associations with substance use and other correlates. J Adolesc Health. 2005; 36(3):214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl A. M. G., & Eitle T. M.Gender, acculturation and alcohol use among Latina/o adolescents: a multi-ethnic comparison. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010; 12(2): 153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I., Kershaw T.S., Lewis J.B., Stasko E.C., Tobin J.N., and Ickovics J.R.. Between synergy and travesty. A sexual risk syndemic among Latina immigrant and non-immigrant adolescents. AIDS and Behavior. 2017; 21(3): 858–869. DOI: 10.1007/s10461-016-1461-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan E. V., Kalichman S. C., Eaton L. A. et al. Co-occurring psychosocial problems and HIV risk among women attending drinking venues in a South African township: a syndemic approach. Ann Behav Med. 2013; 45(2): 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B., Gallaher P., Shakib S., et al. The AHIMSA Acculturation Scale: a new measure of acculturation for adolescents in a multicultural society. J Early Adolesc. 2002; 22(1): 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Davila M., McFall S. L., & Cheng D.Acculturation and depres sive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum Latinas. Matern Child Health J. 2009; 13(3): 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears G. V., Stein J. A., & Koniak-Griffin D.Latent growth trajectories of substance use among pregnant and parenting adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010; 24(2): 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine J. M., Rodriguez M. A., Lapeyrouse L. M., & Zhang M.Recent intimate partner violence as a prenatal predictor of maternal depression in the first year postpartum among Latinas. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011; 14(2): 135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmins C. L. (2002). The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 47(2), 80–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBard C. A., & Gizlice Z. (2008). Language spoken and differ ences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. American Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2021–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw T. S., Magriples U., Westdahl C., Rising S. S., & Ickovics J.Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99(11): 2079–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R. “Bundling” HIV prevention: integrating services to promote synergistic gain. Prev Med. 2008; 46(3): 222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979; 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day N.E., Alegria M, Sribney W.. Social cohesion, social support and health among Latinos in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64(2): 477–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M. G., & O’Brien K M.Psychological health and meaning in life stress, social support, and religious coping in Latina/Latino immigrants. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2009; 31(2): 204–227. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett L. J., Iturbide M. I., Torres Stone R. A., McGinley M., Raffaelli M., & Carlo G.Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007; 13(4): 347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D., & Bates L. M.Latino health paradoxes: empirical evidence, explanations, future research, and implications. In Latinas/os in the United States: Changing the face of America. 2008; 101–113. Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer R. A., Powers D. A., Pullum S. G., Gossman G. L., & Frisbie W. P.Paradox found (again): infant mortality among the Mexican-origin population in the United States. Demography. 2007; 44(3): 441–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingate M. S., & Alexander G. R.The healthy migrant theory: variations in pregnancy outcomes among US-born migrants. Soc Sci Med. 2006; 62(2):491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman R, Eng E, Simán F, Rhodes SD. Exploring the sexual health priorities and needs of immigrant Latinas in the southeastern US: a community-based participatory research approach. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011; 23(3): 236–248. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedlin M. G., Decena C. U., & Oliver-Velez D.Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005; 97(7 Suppl): 32S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraido-Lanza A. F., Chao M. T., & Florez K. R.Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation?: Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005; 61(6): 1243–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B., Bridges M., Bein E. et al. The health and cognitive growth of Latino toddlers: at risk or immigrant paradox?. Matern Child Health J. 2009; 13(6): 755–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]