Abstract

Background:

Image-guided fine-needle aspiration has emerged as an effective diagnostic tool for precise diagnosis of deep-seated lesions. Although occasional studies have made an attempt to classify the gallbladder carcinoma on cytology, literature lacks the standardized cytological nomenclature system used for it. The present study was conducted to study the role of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in diagnosis of gallbladder lesions with an attempt of cytomorphological classification.

Methods:

The study included cases of image-guided FNAC of the gallbladder over a period of 3½ years. An attempt was made to categorize gallbladder lesions on basis of architectural and cytomorphological features along with analysis of management.

Results:

The study included 433 cases and lesions were categorized on FNAC into five categories ranging from Category 1 (inadequate), Category 2 (negative for malignancy), Category 3 (atypical cells), Category 4 (highly atypical cells suggestive of malignancy), and Category 5 (positive for malignancy). The most common architectural pattern observed on FNAC of neoplasm was sheets and acini with predominance of columnar cells and adenocarcinoma being the most common malignancy. The histopathological diagnosis was available in 93 cases with cytohistopathological concordance of 94.4% in malignant cases.

Conclusions:

Image-guided FNAC plays an important role in diagnosis of gallbladder lesions with minimal complications. The cytomorphological classification of gallbladder lesions provides an effective base for accurate diagnosis and management. Category 3 and 4 are the most ambiguous category on FNAC which should be managed by either repeat FNAC or surgery in the light of worrisome radiological features. The vigilant examination of architectural pattern and cytomorphological features of the smears may be helpful in clinching the diagnosis and precisely subtyping malignant tumors along with prognostication of these tumors.

Keywords: Architectural pattern, categorization, cytomorphological features, fine-needle aspiration cytology, gallbladder

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder diseases are common worldwide with gallbladder carcinoma being the most common malignant tumor of the biliary tract.[1] Worldwide, its incidence is 1.3% with age-standardized rate of 22/100,000 person per year and mortality of 1.7%.[2] This carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis which may not only be related to its aggressive behavior but also due to delayed diagnosis.[3] This delay in diagnosis may be due to the nonspecific symptoms, absence of clinical suspicion, or specific markers for diagnosis.[4] In addition, the biopsy is also comparatively inaccessible due to the deep-seated position of this organ. Although radiological examination including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in diagnosing gallbladder lesions, differentiation of some benign conditions such as adenomyomatosis and xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis may also pose problem in differentiation from gallbladder carcinoma radiologically.[5] Recently, US- or CT-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has emerged as an easy and effective diagnostic tool for precise diagnosis of gallbladder lesions.[6,7] Although occasional studies have made an attempt to classify the gallbladder carcinoma on cytology, the literature search lacks the standardized cytological terminology and nomenclature system used for gallbladder lesions on FNAC.[7] The standard system may not only be helpful in clinching accurate diagnosis of gallbladder lesions but also be useful in avoiding interinstitutional bias across the world.

The present study was, therefore, conducted to study the role of FNAC in diagnosis of gallbladder lesions. In addition, an attempt was also made for cytomorphological classification of these lesions.

METHODS

The retrospective study included all the cases of gallbladder which underwent FNAC examination over a period of 3½ years from January 2014 to June 2017. The cytological smears were retrieved from the archives of the department of pathology and blindly reviewed by two cytopathologists. FNAC was performed under image guidance (ultrasonography [USG] or CT guided), and rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) was performed for all cases. The 22-gauge lumbar puncture (needle) was used for FNA in which localization of the needle was done by radiologist under image guidance and aspiration was done by cytopathologist. Maximum two passes were done for any lesion and at least 5–6 slides were prepared. The on-site adequacy of the smears was assessed by rapid staining using toluidine blue, and smears of cases which were considered inadequate on aspiration were re-aspirated instantaneously. Air-dried smears were stained by May Grunwald Giemsa, and wet-fixed smears were stained by hematoxylin and eosin and Papanicolaou stains. The relevant clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings were noted for all the cases. All the smears were assessed for the adequacy of the smears, cellularity, and arrangement of the cells. The smears were considered inadequate which showed either only blood, necrosis, mucous, or only occasional epithelial cells where cytological opinion was not possible. The cellularity of the smears was graded as paucicellular, moderately cellular, or cellular, while arrangement of the cells was noted according to the formation of sheets, papillae, acini, cluster, or dispersed singly. The detailed cellular features with pleomorphism (mild, moderate, or severe) and the presence of columnar cells, squamous cells, clear cells, signet ring cells, giant cells, spindle cells, and intra- and extracellular mucin were also evaluated. The severity and type of inflammation with the presence or absence of necrosis were also assessed for all lesions. An attempt was made to categorize and subcategorize gallbladder lesions on FNAC on the basis of above features. Histopathological and immunochemical diagnosis was noted for cases in which it was available and correlated with cytomorphological diagnosis.

RESULTS

The study included a total of 433 cases which underwent FNAC of the gallbladder in the study. The male-to-female ratio was 1:2.4, and the mean age was 54.93 years with range of 25–95 years. Histopathological examination was available for 93 cases. Table 1 shows the broad categorization of the gallbladder lesions on FNAC. Category 2 (negative for malignancy) included cases which were either inflammatory or observed reactive/benign epithelium suggestive of benign neoplasm or inflammatory lesion [Figure 1]. Category 3 included cases which showed atypical cells difficult to categorize as benign or malignant lesion, while Category 4 observed highly atypical cells suspicious or suggestive of malignancy. Repeat FNAC was performed in 13 cases within the period of 1 month in cases which were inadequate on first aspirate (3 cases), necrotic (3 cases), or showed atypical cells (3 cases). Four cases which were although showing benign cells on first aspiration were followed by repeat aspiration as there was high clinicoradiological suspicion of carcinoma for them. Of these 13 cases, 10 cases (76.9%) were diagnosed as adenocarcinoma on repeat FNAC. All the cases which showed atypical cells were positive for adenocarcinoma on repeat FNAC. Table 2 shows the architectural patterns and cellular morphology observed on FNAC of the gallbladder. The most common pattern observed was sheets and acini with predominance of columnar cells. Table 3 shows the cytological diagnosis and cytohistopathological correlation in cases in which histopathology was done. The histopathological diagnosis was available in 93 cases, and the cytohistopathological concordance in malignant cases was observed to be 94.4%.

Table 1.

Broad categorization of gallbladder lesions on fine-needle aspiration cytology

| Category | Diagnostic group | Number of cases | Percentage of total cases (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category I | Inadequate | 34 | 7.8 |

| Category II | Benign (reactive/inflammatory/benign neoplasm) | 50 | 11.5 |

| Category III | Atypical cells (equivocal for benign or malignant lesion) | 23 | 5.3 |

| Category IV | Atypical cells suggestive or suspicious of malignancy | 19 | 4.3 |

| Category V | Positive for malignancy | 307 | 70.9 |

| Total | 433 | ||

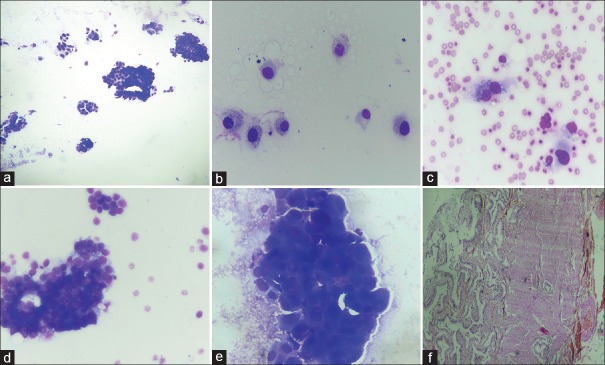

Figure 1.

(a and b) Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with diagnostic Category 1 of benign lesions revealing uniform epithelial sheets. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×40; H and E, ×40). (c and d) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with diagnostic Category 3 of atypical cells showing nuclear overlapping and mild pleomorphism. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×40; H and E, ×40). (e and f) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with diagnostic Category 4 of atypical cells suspicious of malignancy with few cells showing moderate pleomorphism in necrotic background. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×40; H and E, ×40)

Table 2.

Architectural pattern and cytomorphological features observed on fine-needle aspiration cytology of gallbladder carcinoma

| Cytological features | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Architectural pattern | |

| Papillae | 22 (7.1) |

| Acini | 220 (71.6) |

| Sheets | 235 (76.5) |

| Rosettes | 5 (1.6) |

| Nuclear molding | 5 (1.6) |

| Cellular morphology | |

| Columnar cells | 120 (39) |

| Signet ring cells | 3 (0.9) |

| Squamous cells | 19 (6.1) |

| Small cells | 5 (1.6) |

| Clear cells | 2 (0.6) |

| Spindle cells | 1 (0.3) |

| Giant cells | 1 (0.3) |

| Intracellular mucin | 19 (6.1) |

| Nuclear pleomorphism | |

| Mild | 59 (19.2) |

| Moderate | 147 (47.8) |

| Severe | 101 (32.8) |

| Nuclear chromatin | |

| Fine chromatin | 20 (6.5) |

| Vesicular chromatin | 182 (59.2) |

| Coarse chromatin | 100 (32.5) |

| Salt and pepper chromatin | 5 (1.6) |

| Mitotic figures | |

| <5/high-power field | 74 (24.1) |

| 5-10/high-power field | 144 (46.9) |

| >10/high-power field | 89 (28.9) |

| Background | |

| Necrosis | 192 (62.5) |

| Mucin | 22 (7.1) |

| Inflammatory | 139 (45.2) |

| Keratinous material | 17 (5.5) |

Table 3.

Cytological diagnosis and cytohistopathological correlation in diagnosis of gallbladder lesions

| Cytological diagnosis | Number of cases | Histopathological diagnosis available | Histopathological diagnosis | Cyto-histo concordance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate (Category I) | 34 | 16 | Chronic cholecystitis-4 | - |

| Adenocarcinoma-12 | ||||

| Benign/reactive (Category II) | 50 | 26 | Chronic cholecystitis-21 | 96.1 |

| Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis-4 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma-1 | ||||

| Atypical cells (Category III) | 23 | 18 | Chronic cholecystitis-4 | - |

| Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis-8 | ||||

| Adenomatous hyperplasia-2 | ||||

| Adenoma-1 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma-3 | ||||

| Atypical suspicious or suggestive of carcinoma (Category IV) | 19 | 15 | Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis-1 | 80 |

| Adenomatous hyperplasia-1 | ||||

| Adenoma-1 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma-10 | ||||

| Small-cell carcinoma-1 | ||||

| Adenosquamous carcinoma-1 | ||||

| Malignant neoplasms (Category V) |

307 | 18 | 17 | 94.4 |

| 220 | 6 | Adenoma-1 | 83.3 | |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | Moderately differentiated Adenocarcinoma-3 | |||

| Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma-2 | ||||

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 19 | 1 | Mucinous adenocarcinoma-1 | 100 |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 22 | 0 | ||

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 33 | 8 | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma-6 | 100 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma-2 | ||||

| Undifferentiated tumor | 2 | 1 | Giant cell tumor-1 | 100 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 6 | 0 | ||

| Small-cell carcinoma | 2 | 1 | Small-cell carcinoma-1 | 100 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 3 | 1 | Carcinoid tumor-1 | 100 |

DISCUSSION

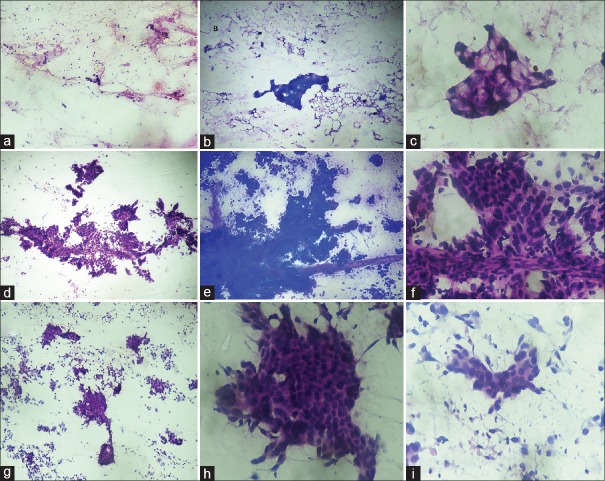

The gallbladder lesions including carcinoma show variable geographical distribution and are more commonly seen in Northern India, Ecuador, Chile, and Poland with female preponderance.[4] The present study also showed increased female-to-male ratio with maximum number of cases being malignant (70.9%). FNAC under USG/CT guidance has emerged as an easy, cost-effective, and useful diagnostic tool to evaluate deep-seated lesions. FNAC of the gallbladder is especially important as the lesions not only lack specific symptoms and clinical presentation but also biopsy is also difficult due to its inaccessibility and association with more complications. The use of standardized terminology classification has been recommended in cytological diagnosis of various organs including thyroid, pancreatobiliary, urine, and cervicovaginal smears so as to avoid interlaboratory diagnostic bias and also helping in management of these cases.[8,9] Although FNAC of the gallbladder is commonly done, only a few large studies have described the cytomorphological categorization of gallbladder lesions.[6,7] The present study categorized the gallbladder lesions in five basic categories ranging from Category 1 (inadequate) to Category 5 of malignant tumors. The rate of inadequacy was 7.8%, which is almost comparable to other studies in which inadequacy rate ranged from 9.2 to 10.2%.[6,7,9] The rate of inadequacy is comparatively low in the present setting as ROSE was performed in all the cases which underwent FNAC. Category 3 is the most heterogeneous category which included cases showing equivocal features of both benign and malignant lesions. The smears in this category were hypercellular, showed cellular overlapping, mild pleomorphism, and had pale cytoplasm with enlarged nuclei but with mostly uniform chromatin and occasional mitotic figures [Figure 1]. It was difficult to categorize these lesions as either reactive gallbladder lesions including xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis and adenomatous hyperplasia or malignancy. The study observed that definite diagnosis was possible in 91.3% of total cases showing atypical cells (21/23 cases) by either repeat FNAC or surgery. Category 4 included cases which were mostly hemorrhagic or necrotic and showed occasional acini with mild to moderately pleomorphic cells and nuclei with coarse chromatin. The cytological features were suspicious or suggestive of carcinoma, but the cytological material was not enough to give definite diagnosis of carcinoma [Figure 1]. Surgery was performed in 15/19 cases of Category 4, and carcinoma was diagnosed in 80% of these cases. The institutional policy for management of Category 3 was either repeat FNAC or surgery in the light of worrisome radiological features, while surgery was recommended for Category 4 lesions. It was also observed that xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis was the most common lesion (44.4%) which was histopathologically diagnosed in cases of Category 3. The histiocytes and macrophages with foamy cytoplasm and large nucleus mimicked adenocarcinoma cells, and thus, diagnosis of equivocal atypical cells was rendered. Rana et al. also observed that cases which were diagnosed as suspicious of malignancy on FNAC showed either false positive or false negative involving xanthogranulomatous changes.[6] An important clue to avoid false-positive diagnosis is nuclei showing minimal anisonucleosis, bland chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and background of inflammatory and foam cells and thus favoring xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis [Figure 2]. The present study suggests that cytological examination of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis may lead to false-positive diagnosis, and therefore, cells showing such changes may be placed in Category 3 if definitive diagnosis is not possible. It is even more important because radiologically also, it is difficult to differentiate between xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis and carcinoma.[5] The diagnostic confusion increases further as adenocarcinoma may be associated with coexisting xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, and thus, careful examination of the smears is required to avoid any pitfall resulting in false-negative diagnosis.[10] Adenomatous hyperplasia and adenoma are other entities which led to the false-positive diagnosis in our study. The confusion arose as both these entities show increased cellularity with mild-to-moderate nuclear atypia and worrisome radiological features. The authors preferred to keep them in either Category 3 or 4, but the final histopathological diagnosis confirmed them to be benign lesions. It is, therefore, suggested that cellular smears showing monolayered sheets with mostly uniform nuclear chromatin and small nucleoli which may show some nuclear atypia may be finally diagnosed as benign lesions of either adenomatous hyperplasia or adenoma [Figure 2]. Gallbladder tuberculosis, although rare, is another lesion which may be misdiagnosed as carcinoma and it should always be kept in mind in providing cytological diagnosis, especially in endemic regions.[11] A vigilant examination of the smear may help in identifying occasional epithelioid cell granuloma in necrotic background and clinching the correct diagnosis. However, in the present study, none of the cases of gallbladder tuberculosis was observed.

Figure 2.

(a-c) A case of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis which on fine-needle aspiration cytology was kept in diagnostic Category 3 showed cellular smears with cells having nuclei with minimal anisonucleosis, bland chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and foamy cytoplasm. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×10, ×40). (d-f) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder led to false-positive diagnosis of Category 4 in a case which later histopathologically proved to be adenomatous hyperplasia (f). The smears were cellular, showed moderate pleomorphism but close examination of nuclei showed mostly uniform chromatin (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×40; H and E, ×20)

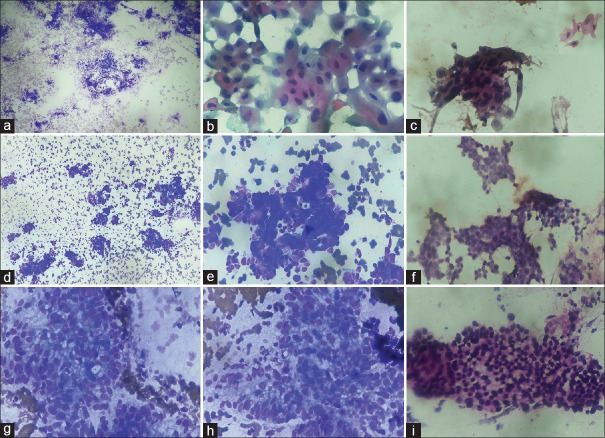

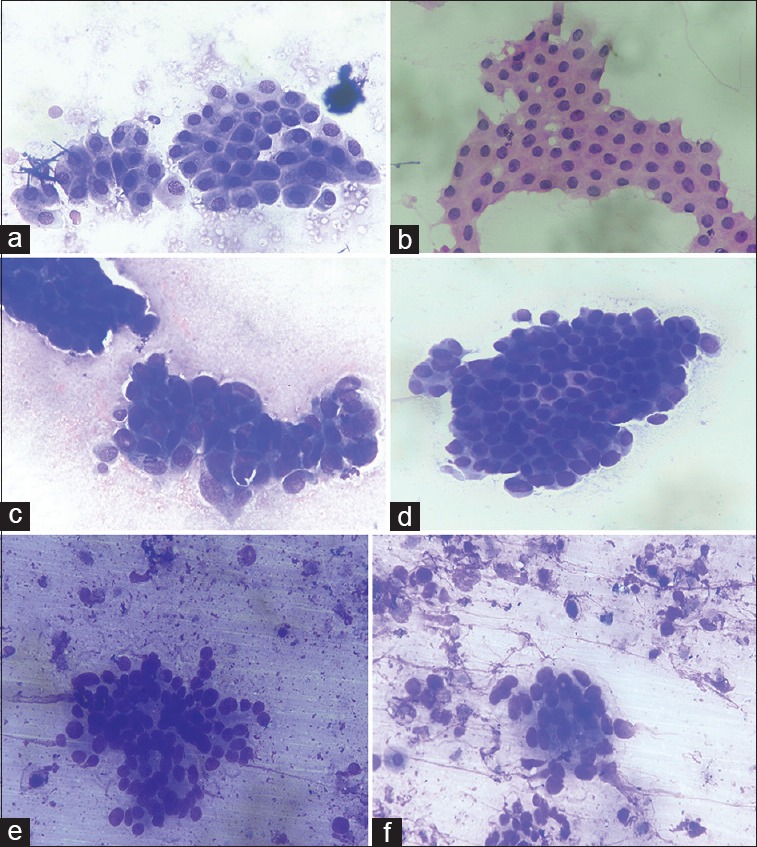

The most common cytological diagnosis in the present study was Category 5 or positive for malignancy which constituted 70.9% of total cases. The histological subtype of gallbladder carcinoma is considered to be an important prognostic factor, and therefore, the typing of gallbladder carcinomas is required for appropriate management of these cases.[4,12] An attempt to classify gallbladder carcinoma according to architectural pattern and cellular features was done in this study so that it may guide the clinician to assess the prognosis of these cases. Previously, Yadav et al. also attempted the WHO histological classification on FNA material of gallbladder carcinoma.[7] The adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified was the most common carcinoma in the present study and was diagnosed when the smears revealed mostly acini and sheets with columnar to rounded cells showing nuclei with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli in either inflammatory or necrotic background. Papillary carcinoma is considered to have better prognosis, and we also found that cytological smears showing preponderance of true papillae with fibrovascular cores showed mild cytological atypical with fewer mitotic figures [Figure 2].[4,13] Mucinous adenocarcinoma is another variant of gallbladder carcinoma which is poorly described in literature and comprises 2.5% of all gallbladder carcinomas with poor prognosis.[4,14] The criterion for diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma is the presence of >50% of extracellular mucin.[1] The present study observed 6.1% of this variant with moderately pleomorphic cells floating in lakes of extracellular mucin [Figure 3]. Gallbladder neuroendocrine tumor was rare in the present study (0.9%), and the cytological diagnosis was based on the presence of rosettes, stippled nuclear chromatin, and absent or occasional mitotic figures. Increased necrosis, mitotic activity, apoptosis, nuclear molding, and coarse chromatin with inconspicuous nucleoli favored small-cell carcinoma which constituted only 0.6% of all malignancies [Figure 4]. Neuroendocrine tumors and small-cell carcinoma are also rare tumor and carry poor prognosis, and cytology plays an important role in their diagnosis and thus necessary for prognostication of these tumors.[15] Pure squamous cell carcinoma constituted 1.9% in the present study which was characterized by keratinized cells, tadpole cells in background of keratinous debris, or inflammation [Figure 4]. The squamous cell carcinoma may be associated with adenocarcinoma component for diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma, but in our study, none of the cases showed cytological feature of adenosquamous carcinoma. Roa et al. also observed only 1% of pure squamous cell carcinoma in series of 34 squamous and adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder.[16] This carcinoma commonly extends to the liver and other neighboring structures and is diagnosed at advanced stage and thus has poor prognosis.[16,17] Thus, it is suggested that close cytological examination of smears is essential to precisely subtype the malignant tumors of the gallbladder which may thus be helpful in prognostication of these tumor. The authors also suggest that larger studies across different institutions may be done so that uniform reporting system is made for FNAC of gallbladder lesions.

Figure 3.

(a-c) Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with mucinous adenocarcinoma revealing abundant intra- and extracellular mucin (Papanicolaou, ×10 and ×40; May Grunwald Giemsa, ×10). (d-f) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with papillary adenocarcinoma showing true papillae with mild cytological atypia (H and E, ×10 and ×40; May Grunwald Giemsa, ×10). (g-i) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with adenocarcinoma showing predominance of columnar cells (Papanicolaou, ×10 and ×40)

Figure 4.

(a-c) Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with squamous cell carcinoma showing tadpole cells with keratinization and ink dot nuclei. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×10; Papanicolaou, ×40). (d-f) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with neuroendocrine tumor showing cells arranged in rosettes with nuclear molding and having stippled chromatin. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×10 and ×40; Papanicolaou; ×40). (g-i) fine-needle aspiration cytology of the gallbladder with clear cell carcinoma showing mild to moderately pleomorphic cells having pale to clear cytoplasm. (May Grunwald Giemsa, ×40; H and E, ×40)

CONCLUSIONS

Thus, image-guided FNAC plays an important role in diagnosis of gallbladder lesions with minimal complications. The cytomorphological classification of gallbladder lesions provides an effective base for accurate diagnosis and management of these cases. Category 3 and 4 are the most ambiguous category on FNAC of the gallbladder which should be managed by either repeat FNAC or surgery in the light of worrisome radiological features. The vigilant examination of architectural pattern and cytomorphological features of the smears may be helpful in clinching the diagnosis and precisely subtyping the malignant tumors of the gallbladder which is essential to assess the prognostication of these tumors. It is further suggested that larger studies across different institutions may be done on FNAC gallbladder so that uniform reporting system is formulated for gallbladder cytology.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

SC: Conception and design of study, collection and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript

HC: Collection and interpretation of data, literature search, intellectual input in drafting of manuscript

SKS: Collection and interpretation of data and input in drafting manuscript

SS: Clinical interpretation of data and intellectual input in drafting of manuscript

All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors collectively take the responsibility of the research work and mantainence of relevant documentation. The work was ethically approved by the institutional research committee.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

Adenocarcinoma NOS - Adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified

CT guided - Computed tomography guided

FNAC - Fine needle aspiration cytology

USG guided - Ultrasonography guided

WHO - World Health Organization.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Smita Chandra, Email: smita_harish@yahoo.com.

Harish Chandra, Email: drharishbudakoti31@yahoo.co.in.

Sushil Kumar Shukla, Email: sushilshukla1387@gmail.com.

Shantanu Sahu, Email: skshau@srhu.edu.in.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albores-Saavedra J, Kloppel G, Adsay NV, Sripa B, Crawford JM, Tsui WM, et al. Carcinoma of the gall bladder and extra hepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010. pp. 263–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soorjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11. 1.0. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 02]. GLOBOCAN 2012. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutta U. Gallbladder cancer: Can newer insights improve the outcome? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:642–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanthan R, Senger JL, Ahmed S, Kanthan SC. Gallbladder cancer in the 21st century. J Oncol. 2015;2015:967472. doi: 10.1155/2015/967472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshmukh SD, Johnson PT, Sheth S, Hruban R, Fishman EK. CT of gallbladder cancer and its mimics: A pattern-based approach. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:527–36. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9907-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rana C, Krishnani N, Kumari N. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of gallbladder lesions: A study of 596 cases. Cytopathology. 2016;27:398–406. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav R, Jain D, Mathur SR, Sharma A, Iyer VK. Gallbladder carcinoma: An attempt of WHO histological classification on fine needle aspiration material. Cytojournal. 2013;10:12. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.113627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cibas ES, Ali SZ. NCI Thyroid FNA State of the Science Conference. The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658–65. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPHLWMI3JV4LA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Ali SZ, Genevay M, Stelow E, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Standardized terminology and nomenclature for pancreatobiliary cytology: The papanicolaou society of cytopathology guidelines. Cytojournal. 2014;11:3. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.133343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnani N, Shukla S, Jain M, Pandey R, Gupta RK. Fine needle aspiration cytology in xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, gallbladder adenocarcinoma and coexistent lesions. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:508–14. doi: 10.1159/000328522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandey M, Pathak AK, Gautam A, Aryya NC, Shukla VK. Carcinoma of the gallbladder: A retrospective review of 99 cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1145–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1010652105532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer. 1992;70:1493–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1493::aid-cncr2820700608>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1986. Tumors of the gallbladder and extra hepatic bile ducts. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 2nd ser. Fascicle 22; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dursun N, Escalona OT, Roa JC, Basturk O, Bagci P, Cakir A, et al. Mucinous carcinomas of the gallbladder: Clinicopathologic analysis of 15 cases identified in 606 carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1347–58. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2011-0447-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav R, Jain D, Mathur SR, Iyer VK. Cytomorphology of neuroendocrine tumours of the gallbladder. Cytopathology. 2016;27:97–102. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roa JC, Tapia O, Cakir A, Basturk O, Dursun N, Akdemir D, et al. Squamous cell and adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder: Clinicopathological analysis of 34 cases identified in 606 carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1069–78. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta P, Gupta RK. Preoperative diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the gallbladder by ultrasound-guided aspiration cytology: Clinical and cytological findings of nine cases. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:638–41. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]