Abstract

Objectives

Syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) omits asymptomatic infections, particularly among women. Accurate point-of-care assays may improve STI care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). We aimed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the Xpert Chlamydia trachomatis/Neisseria gonorrhoeae (CT/NG) and OSOM Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) Test as part of a STI care model for young women in South Africa.

Design

Diagnostic evaluation conducted as part of a prospective cohort study (CAPRISA 083) between May 2016 and January 2017.

Setting

One large public healthcare facility in central Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Participants

247 women, aged 18–40 years, attending for sexual and reproductive services to the clinic. Pregnant and HIV-positive women were excluded.

Outcomes

Diagnostic performance of the Xpert CT/NG and OSOM TV assays against the laboratory-based Anyplex II STI-7 Detection. All discordant results were further tested on the Fast Track Diagnostics (FTD) STD9 assay.

Results

We obtained vaginal swabs from 247 women and found 96.8% (239/247) concordance between Xpert and Anyplex for CT and 100% (247/247) for NG. All eight discrepant CT results were positive on Xpert, but negative on Anyplex. FTD STD9 confirmed three positive and five negative results, giving a confirmed prevalence of CT 15.0% (95% CI 10.5 to 19.4), NG 4.9% (2.2–7.5) and TV 3.2% (1.0–5.4). Sensitivity and specificity of Xpert CT/NG were 100% (100-100) and 97.6% (95.6–99.7) for CT and 100% (100-100) and 100% (100-100) for NG. The sensitivity and specificity of OSOM TV were 75.0% (45.0–100) and 100% (100-100).

Conclusion

The Xpert CT/NG showed high accuracy among young South African women and combined with the OSOM TV proved a useful tool in this high HIV/STI burden setting. Further implementation and cost-effectiveness studies are needed to assess the potential role of this assay for diagnostic STI testing in LMICs.

Trial registration number

NCT03407586; Pre-results.

Keywords: sexually transmitted infections, point-of-care testing, Xpert CT/NG, South Africa

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first evaluation of the diagnostic performance of the Xpert CT/NG point-of-care assay to detect chlamydia and gonorrhoea from a low- and middle-income country.

Study participants were young South African women, who are at highest risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV in Africa, and have been prioritised for diagnostic STI testing and treatment by the WHO.

The limitations of our study were that it was conducted at a single site, only among women, and had a relatively small sample size (n=247).

Introduction

The WHO estimates that 357 million new cases of four curable sexually transmitted infections (STIs), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) and Treponema pallidum occur annually among people aged 15–49 years, with 63 million of them in Africa.1 These STIs are responsible for foetal and neonatal deaths, pelvic inflammatory disease resulting in ectopic pregnancies, chronic pelvic pain and infertility2; and are major risk factors for HIV infection, increasing transmission risk by 2- to 3-fold.3 In addition, among women, up to 80% of STIs are asymptomatic,4 and therefore remain undiagnosed by the standard syndromic management approach adopted by many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Recent WHO and South African guidelines recommend the introduction of diagnostic testing for high-risk populations.1 5 However, the best diagnostic assays to use in LMIC settings like South Africa are unknown.

In high-income countries, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are recommended and widely used for the detection of CT and NG. Cheaper and faster diagnostic technologies are being developed and provide an opportunity to design diagnostic STI care models for LMICs. One of these assays is the point-of-care (POC) Xpert CT/NG performed on the GeneXpert System (Cepheid, Sunnydale, California, US), a real-time PCR test for the rapid detection of CT and NG, which was US FDA cleared in 2012 and received the European CE mark in 2016. This assay may be particularly relevant to the South African setting, because more than 4000 GeneXpert modules have already been placed in public healthcare settings for the rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB).6 Multi-disease testing for HIV viral load monitoring, early infant diagnosis and TB using the GeneXpert platform was found to be feasible in rural Zimbabwe.7 Potentially, the existing infrastructure could be expanded to form pilot sites for diagnostic STI care serving high-risk groups, such as young or pregnant women, sex workers and men who have sex with men. However, while some studies have evaluated the diagnostic performance of Xpert CT/NG in high-income countries,8 9 we are not aware of any studies from LMICs, where the need is greatest.

Considering the relatively high cost of the Xpert TV cartridge (~USD 19.00), we decided to complement the Xpert CT/NG with the OSOM TV antigen detection assay (Sekisui, Lexington, MA, US) and Gram stain microscopy, in order to offer the participants a comprehensive 2-hour STI testing alternative to syndromic management.10 The advantage of the OSOM TV assay is that it is relatively cheap (~USD 8.00), has a rapid processing time (~10 min) and has shown higher accuracy than wet mount microscopy, especially in women.11 12

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the POC Xpert CT/NG and OSOM TV assays in young women presenting to an urban primary healthcare clinic in South Africa.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

The CAPRISA 083 prospective cohort study was conducted at a large public healthcare clinic in Durban, South Africa between May 2016 and January 2017 and was previously described in detail.10 Briefly, the study evaluated a clinic-based STI care model composed of POC STI testing, immediate treatment and expedited partner therapy (EPT) for young women at high HIV risk. Non-pregnant, HIV-negative women, aged 18–40 years, attending for sexual and reproductive services were eligible, and once consented, were enrolled consecutively into the study. Women diagnosed with CT, NG or TV based on POC testing were offered immediate supervised treatment with single dose antibiotics on the same visit. Treatment regimens followed international guidelines, and were compatible with national guidelines: ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscular and azithromycin 1 g oral for NG, azithromycin 1 g oral for CT, and metronidazole 2 g oral for TV.13 14

Evaluation of POC STI assays

At enrolment, a nurse with experience in sexual health collected two vaginal swabs for POC testing on the Xpert CT/NG and the OSOM TV assays, and one Eswab (Copan, Brescia, Italy) specimen, which was sent to the regional National Health Laboratory Services reference laboratory for DNA extraction and parallel testing on the Anyplex II STI-7 Detection assay (Seegene, Seoul, Korea) within 24 hours of sample collection, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute requirements. Considering that all participants received their results during the same visit and the tests were performed in the clinic, we used the term ‘point-of-care’ for both assays, in line with the following consensus definition: ‘a point-of-care test…is a test to support clinical decision making, which is performed by a qualified…staff nearby the patient…during or very close to the time of consultation, to help the patient and physician to decide upon the best suited approach, and of which the results should be known at the time of the clinical decision making’.15 All POC tests were processed according to manufacturers’ specification (www.sekisuidiagnostics.com/products/130-osom-trichomonas-test and www.cepheid.com/us/cepheid-solutions/clinical-ivd-tests/sexual-health/xpert-ct-ng) by laboratory technologists with experience using the GeneXpert platform at the clinic laboratory, but no access to participant clinical data. Reference laboratory staff were blinded to the POC test results and had no access to participant clinical data. Any discordant results comparing the Xpert CT/NG and OSOM TV against the Anyplex II STI-7 assay were retested on a third multiplex real-time PCR assay, the FTD STD9 (Fast Track Diagnostics, Silema, Malta). The Anyplex II STI-7 and FTD STD9 were chosen as confirmatory tests, because they are both CE marked and are commercially available in South Africa. For epidemiological purposes, these assays also provided the opportunity to determine the prevalence of sexually transmitted organisms not routinely screened for in surveillance studies. Positive result cut-offs for all assays were prespecified by the manufacturers.

Data analysis

Clinic laboratory data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA), checked for internal validity and analysed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, US). The sample size was predetermined to assess the primary outcome of the CAPRISA 083 cohort study, which assessed the reduction in genital tract proinflammatory cytokines after POC testing, immediate treatment and EPT among women diagnosed with STIs. Reference laboratory results were imported and analysed at the end of the CAPRISA 083 study. Diagnostic accuracy of the assays was measured by calculating sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) and 95% CI using the Wald method.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of and recruitment to the study. However, the syndromic STI management approach in South Africa often leaves women untreated and return to clinics with recurrent symptoms and partner notification and treatment services are inadequate. These experiences by patients led to the study design, and the implementation of POC testing and EPT in the clinic. Patients took part in focus group discussions and were able to provide feedback to the study team on their experiences with the POC STI testing model.9

Results

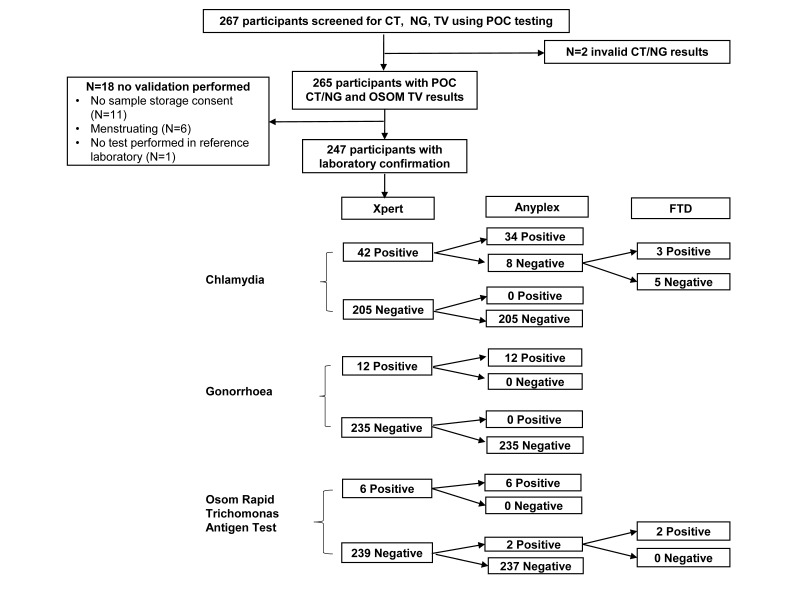

A total of 267 women with median age 23 years (IQR 21–26) enrolled into the CAPRISA 083 study, and 23.6% (63/267) were diagnosed with at least one of the three STIs (CT, NG or TV) using Xpert CT/NG and OSOM TV POC testing at the clinic. We obtained vaginal Eswab specimen from 247/267 (92.5%) women for the diagnostic evaluation at the reference laboratory. The 20 women not included in the evaluation either did not provide consent for sample storage (n=11), were menstruating (n=6), had an invalid Xpert CT/NG result (n=2) or did not have a test processed in the reference laboratory (n=1). The study flow is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow and results of the diagnostic evaluation of the Xpert CT/NG and Osom TV assays.

The confirmed prevalence among the 247 women evaluated was 15.0% (95% CI 10.5 to 19.4) for CT, 4.9% (2.2–7.5) for NG and 3.2% (1.0–5.4) for TV. In addition, Anyplex testing revealed a 4.9% (2.2–7.5) prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium, 33.6% (27.7–39.5) Mycoplasma hominis, 51.8% (45.6-58.1) Ureaplasma parvum and 19.0% (14.1–23.9) Ureaplasma urealyticum. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of Xpert CT/NG and OSOM TV assays are shown in table 1. Overall we found 96.8% (239/247) concordance between the Xpert and Anyplex for CT and 100% (247/247) concordance for NG. All eight discrepant CT results were positive on Xpert, but negative on Anyplex. Testing on FTD STD9 confirmed three positive and five negative results. The Xpert cycle thresholds of the five discordant results reached 26.3 to 38.6 cycles, with two values greater than 38 cycles, indicating potential sampling or testing variation. The concordance between OSOM TV and Anyplex was 99.2% (245/247) with two discordant cases undetected on the OSOM TV assay, but positive on confirmatory testing. Most participants (265/267, 99.3%) received their POC results on the day of sampling, and were offered immediate treatment, if indicated.

Table 1.

Evaluation of the Xpert CT/NG and OSOM TV against the Anyplex II STI-7 Detection and FTD STD9 assays (n=247)

| POC assay | Anyplex II STI-7 Detection +/- FTD STD9 | Accuracy with 95% CI | ||

| Positive | Negative | |||

| Xpert CT | Positive | 37 | 5 | Sensitivity=100% (100% to 100%) Specificity=97.6% (95.6% to 99.7%) PPV=88.1% (78.3% to 97.9%) NPV=100% (100% to 100%) |

| Negative | 0 | 205 | ||

| Xpert NG | Positive | 12 | 0 | Sensitivity=100% (100% to 100%) Specificity=100% (100% to 100%) PPV=100% (100% to 100%) NPV=100% (100% to 100%) |

| Negative | 0 | 235 | ||

| OSOM TV | Positive | 6 | 0 | Sensitivity=75.0% (45.0% to 100%) Specificity=100% (100% to 100%) PPV=100% (100% to 100%) NPV=99.2% (98.0% to 100%) |

| Negative | 2 | 239 | ||

FTD, Fast Track Diagnostics; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; POC, Point-of-care; TV, Trichomonas vaginalis.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to evaluate the performance of the Xpert CT/NG, as well as the OSOM TV, within a clinic-based diagnostic care model to rapidly detect CT, NG and TV in a high STI/HIV burden setting in South Africa. The Xpert CT/NG performed well with a high sensitivity and specificity to diagnose CT and NG, while the OSOM TV showed lower sensitivity, but high specificity. Taken together, these assays could allow diagnosis and management of STIs in one clinical visit.

Our findings are consistent with a study of 1722 women and 1387 men from the US, which found a consistently high diagnostic performance of the Xpert CT/NG testing cervical and vaginal swabs from women, and urine from men and women.8 Sensitivity and specificity of the assay using vaginal swabs was 98.7% and 99.4% for CT and 100% and 99.9% for NG, which was only marginally superior to urine testing in women (97.6%, 99.8% for CT and 95.6%, 99.9% for NG). Similar to our evaluation, this study found a lower PPV of the assay for both CT (88.6%) and NG (91.7%) when using vaginal swabs in their population, while PPVs for urine testing were higher (96.4% and 95.6%). This could indicate that urine samples may be adequate for Xpert CT/NG testing in women, and may prevent unnecessary treatment, especially in populations with lower CT prevalence.

In our study, two out of five ‘false positive’ Xpert CT results had a high cycle threshold above 38 cycles. A validation of 50 randomly selected vulvovaginal samples from a study of pregnant women in Pretoria, South Africa16 also found two positive Xpert CT/NG results with high cycle thresholds that were confirmed negative after testing on the PrestoPlus CT/NG/TV (Microbiome, Ltd., Houten, The Netherlands) and Anyplex assays. This highlights that some caution is needed when interpreting high cycle threshold results, and while retesting may be considered, it also highlights the limitations of comparing two or more highly accurate molecular based assays, that challenge the threshold limits of each other.

Recently, the POC Xpert CT/NG was evaluated as part of a large cluster randomised study in remote community health services in Australia. In keeping with our findings, the assay demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity when performed by nurses and community health workers compared with conventional NAATs for both CT (98.6%, 99.5%) and NG (100%, 99.9%) using either urine samples or vaginal swabs. The authors concluded that this POC STI assay may be particularly suitable for LMICs, where resources are limited and infrastructure is often poor.9

We decided to complement the Xpert CT/NG testing with the OSOM TV antigen detection assay in order to provide the participants with a comprehensive 2-hour STI testing alternative to syndromic management.10 Previous evaluations11 12 of the OSOM TV concur with our finding of a slightly lower sensitivity (92%–98%) than PCR technology, but a consistently high specificity to detect TV (99%). The advantage of this assay is that it is relatively cheap, has a rapid processing time and higher accuracy than wet-prep microscopy, especially in women.12 It is important to note that the decision to use the OSOM TV rather than the Xpert TV was driven by the direct cost of the test. However, the relative costs of scaling up a STI screening programme, including the costs and logistics of a quality assurance and training framework may make the Xpert TV assay still a reasonable addition in the future, even more so, if the company Cepheid decided to launch a CT/NG/TV multiplex cartridge.

The limitations of our study were that it was conducted at one site, only among young women, and had a relatively low sample size. We excluded pregnant women from the CAPRISA 083 cohort study, because they were referred for antenatal care, and were not an appropriate population to pilot the EPT intervention in. However, pregnant women may be an important population to offer POC testing to in the future,16 17 and perhaps combine the testing model with a POC syphilis assay.18 A further limitation of our study was that specimens were not available to repeat discordant results on the Xpert CT/NG platform. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, we report the first clinic evaluation of the diagnostic performance of the Xpert CT/NG assay from a LMIC. Furthermore, we decided to focus on young women, because this population group has been prioritised for diagnostic STI care in WHO and South African guidelines,1 5 and remains at highest risk of HIV acquisition in LMICs.

In conclusion, we found the Xpert CT/NG to be accurate when used at the point of care in a LMIC clinic, and it was complemented well by the OSOM TV assay. Larger implementation studies are required to assess whether the introduction of POC STI testing could be cost effective, and eventually replace the syndromic management approach in South Africa. In the meantime, it seems prudent to prioritise diagnostic STI care for high-risk populations as part of HIV prevention efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all CAPRISA 083 study participants for their contributions to this research. We thank the Ethekwini Municipality Health staff for granting access to the Prince Cyril Zulu Communicable Diseases Centre patients, and the CAPRISA 083 study team for collecting clinical data and specimen.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: NG, AR and AM are the coprincipal investigators, conceived the study and wrote the study protocol. NG, JD, HN recruited the cohort. NG, NM, JN, RS and KM conducted the laboratory evaluation. NG, FO, JD, AM performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript and consented to final publication.

Funding: This study was funded by a United States – South African Program for Collaborative Biomedical Research grant through the South African Medical Research Council and the National Institute of Health (AI116759).

Competing interests: Cepheid Inc loaned two 4-module GeneXpert machines to the study team free-of-charge, but had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa (BFC410/15).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data of this study are available to interested parties on request from the corresponding author: nigel.garrett@caprisa.org.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Sexually Transmitted Infections 2016-2021. Geneva, Switzerland. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246296/1/WHO-RHR-16.09-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 26 Nov 2018).

- 2. Romoren M, Hussein F, Steen TW, et al. Costs and health consequences of chlamydia management strategies among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:558–66. 10.1136/sti.2007.026930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M, et al. Non-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort study. AIDS 1993;7:95–102. 10.1097/00002030-199301000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawkes S, Morison L, Foster S, et al. Reproductive-tract infections in women in low-income, low-prevalence situations: assessment of syndromic management in Matlab, Bangladesh. Lancet 1999;354:1776–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02463-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. South African National AIDS Council. Let our actions count, South Africa’s National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017-2022. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Annual number of GeneXpert modules procured under concessional pricing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/laboratory/status_xpert_rollout_dec_2016.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 26 Nov 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ndlovu Z, Fajardo E, Mbofana E, et al. Multidisease testing for HIV and TB using the GeneXpert platform: A feasibility study in rural Zimbabwe. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193577 10.1371/journal.pone.0193577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaydos CA, Van Der Pol B, Jett-Goheen M, et al. CT/NG Study Group. Performance of the Cepheid CT/NG Xpert Rapid PCR Test for Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1666–72. 10.1128/JCM.03461-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Causer LM, Guy RJ, Tabrizi SN, et al. Molecular test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea used at point of care in remote primary healthcare settings: a diagnostic test evaluation. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:340–5. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garrett NJ, Osman F, Maharaj B, et al. Beyond syndromic management: Opportunities for diagnosis-based treatment of sexually transmitted infections in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One 2018;13:e0196209 10.1371/journal.pone.0196209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegazy MM, El-Tantawy NL, Soliman MM, et al. Performance of rapid immunochromatographic assay in the diagnosis of Trichomoniasis vaginalis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;74:49–53. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nathan B, Appiah J, Saunders P, et al. Microscopy outperformed in a comparison of five methods for detecting Trichomonas vaginalis in symptomatic women. Int J STD AIDS 2015;26:251–6. 10.1177/0956462414534833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health of South Africa. Sexually transmitted infections management guidelines 2015. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health of South Africa, 2015:1–28. https://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/STIguidelines3-31-15cmyk.pdf (accessed 26 Nov 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Atlanta, United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm (accessed 26 Nov 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schols AMR, Dinant GJ, Hopstaken R, et al. International definition of a point-of-care test in family practice: a modified e-Delphi procedure. Fam Pract 2018;35:475–80. 10.1093/fampra/cmx134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peters RPH, de Vos L, Maduna L, et al. Laboratory Validation of Xpert Chlamydia trachomatis/Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Trichomonas vaginalis Testing as Performed by Nurses at Three Primary Health Care Facilities in South Africa. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:3563–5. 10.1128/JCM.01430-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mayanja Y, Mukose AD, Nakubulwa S, et al. Acceptance of treatment of sexually transmitted infections for stable sexual partners by female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155383 10.1371/journal.pone.0155383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phang Romero Casas C, Martyn-St James M, Hamilton J, et al. Rapid diagnostic test for antenatal syphilis screening in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018132 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.