Abstract

Objectives

To introduce serialised medicines into an operational hospital dispensary and assess the technical effectiveness of digital medicine authentication (MA) technology under European Union Falsified Medicines Directive (EU FMD) conditions.

Design

Thirty medicine lines were serialised using 2D data matrix labels and introduced into an operational UK National Health Service (NHS) hospital dispensary. Staff were asked to check medicines for two-dimensional (2D) data matrices and scan those products, in addition to their usual medicine preparation and checking processes. Four per cent of the study medicines were labelled with a 2D barcode which generated a pop-up, identifying the medicine as either authenticated elsewhere (falsified), authenticated here, expired or recalled.

Setting

An NHS teaching hospital based in the UK, the same site as the Naughton et al 2016 study.

Participants

General Pharmaceutical Council registered, accredited accuracy checking technicians and pharmacists.

Primary outcome measures

Average response times, offline issues, instances of incorrect quarantine and workarounds. The EU FMD maximum response time is 300 milliseconds (ms).

Results

During the checking stage of medicine preparation, the average response time for MA in this study was 131 ms. However, 4.67% of attempted authentications experienced offline issues, an increase of 4.23% from the previous study. An increase in offline instances existed alongside an increase in incorrect quarantine.

Conclusions

Digital drug screening has the capability of operating with average response times which are below the maximum EU FMD limit of 300 ms. However, there was an increased incidence of offline errors and cases of incorrect quarantine. The practical and legal implications of supplying a substandard or falsified medicine during offline periods without prior authentication or withholding supply until online status resumes are not yet fully understood.

Keywords: medicine authentication, falsified medicine, substandard medicine, healthcare operations, digital healthcare

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This methodology is the first of its kind to assess medicine authentication (MA) average response times, incorrect quarantine and offline incidents within an active healthcare context.

Evidence of offline issues and their effect on practice is demonstrated in this article.

This study identifies the strengths and limitations of MA technology.

As this study was not conducted at multiple hospitals, it provides case study evidence only.

This research assesses manual MA and does not provide evidence for automated or robotic dispensing systems.

Introduction

The definition of falsified medicine varies internationally.1–3 However, the WHO defines falsified medicines as ‘Medical products that deliberately or fraudulently misrepresent their identity, composition or source’. The WHO defines substandard medicines as ‘Authorised medical products that fail to meet either their quality standards or specifications or both’. Substandard medicines, for example, may be medicines which originated from a legitimate manufacturer, but contain an unintentional ‘Out of specification’ error in their production.4

Instances of substandard and falsified (SF) medicines are usually seen in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), and their administration can lead to side-effects, poor treatment outcomes and death in already life-threatening conditions such as malaria.5–8 However, falsified medicines are not just an issue in LMICs and examples of falsified medicines exist in high-income countries also; for example, a falsified version of an anticancer agent, Avastin®, was discovered, which contained no active ingredient.9 Moreover, there were 11 cases of falsified medicines identified in the UK between 2001 and 2011 and 222 cases of substandard medicines were recalled in the UK during the same period.10

Medicine serialisation regulations are emerging internationally. The US Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA)1 and the EU Falsified Medicines Directive (EU FMD)3 11 are the most widely known of these regulations. The DSCSA relies on a track-and-trace process, where medicines are scanned on transfer of ownership, while the EU FMD has mandated medicine commission at production and digital drug screening or medicine authentication (MA) at the point of supply to the patient, that is, an end-to-end operation. Both regulations aim to identify substandard (recalled or expired) and falsified or counterfeit medicines.

The EU FMD is a pan-European regulation which mandates MA, also known as medicine decommissioning, at the point of supply to the patient and involves the scanning of a two-dimensional (2D) barcode. Manufacturers are currently preparing for prescription only medicine serialisation and are at different stages of preparedness. Manufacturers must serialise products which are manufactured after 9 February 2019 and dispensers must have operations in place to authenticate (scan) the 2D barcode on each pack (medicine container) dispensed after the February deadline.12 The data contained within this 2D data matrix is then digitally cross-checked against a national database to determine whether or not a medicine is recalled, expired or potentially falsified. The FMD mandated MA approach is an entirely new process for much of Europe and will affect every pharmacy throughout the EU. Each European hospital or community pharmacy must be compliant by 9 February 2019. Although, this regulation has been anticipated since 2011, there are low-levels of awareness and understanding among practitioners and a publication by Naughton et al 201613 identified issues regarding the relatively poor operational authentication and detection rate of this approach. Naughton et al 201613 identified accuracy-checking technicians and pharmacists at the checking stage of medicine supply as the best-placed personnel within dispensary operations to carry out the decommissioning process based on the scanning compliance data. The Naughton et al 201613 study did not discuss offline episodes or incorrect quarantine, but did report an average response time of less than 300 milliseconds (ms). These results demonstrated a significant operational quality concern with the digital MA approach.13 If poorly implemented, the EU FMD has the potential to be disruptive to healthcare providers. This paper aims to inform healthcare providers about the potential technical disruptions caused by the incoming legislation.

Methods

Data from the Naughton et al 201613 study was re-examined to identify the incidence of offline errors and incorrect quarantine. The Naughton et al 201613 study methodology was then repeated under near-identical conditions with one alteration to the MA technology. This change involved the inclusion of an audio alert which was suggested by study participants as part of a Delphi-method study.14 This audio alert sounded upon the authentication of a falsified medicine (authenticated elsewhere) or a substandard medicine (expired or recalled). This study generated a large data set which relate to the incoming digital drug screening approach. The objective of this paper is to assess the technical data gathered in the wider study and compare it with previously published and unpublished data from the Naughton et al study in 2016.13. This paper focuses on some of the key technical FMD parameters, that is, offline issues, incorrect quarantine and average response times and observes the workarounds associated with the proposed MA operation. Although, the wider study included multiple objectives, only the three technical objectives below are explored in this paper.

Objectives

To establish MA technology offline frequency (ie, how often the system failed to connect to the medicine verification database) and incorrect quarantine in the repeat study and compare it with previously unpublished data collected as part of the Naughton et al 201613 study.

To identify MA average response times in the repeat study (ie, how long it took for the technology to communicate with the database and return a response) and compare this with the published results in Naughton et al 2016.13

To observe and discuss workarounds associated with the MA approach in the repeat study and to acknowledge the effect of the audio alert on the technical parameters measured in this study.

Study site

This study was performed at the same National Service Hospital (NHS) hospital site that hosted the study by Naughton et al in 2016,13 namely Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Product serialisation method

Medicine product lines were labelled with a pre-programmed 2D barcode sticker (30 product lines in total), twice a week, in the morning and early afternoon for an 8-week period to ensure that medicine lines remained serialised throughout the duration of the 8-week study as per the Naughton et al study in 2016.13 The pre-programmed 2D barcode sticker identified each product as being ’Authenticated', ’Already authenticated here', ’Authenticated elsewhere' (falsified), ’Product recalled', ’Batch recalled' or ’Expired' at frequencies described in table 1.

Table 1.

A description of each pop-up alert and corresponding frequency throughout the investigated sample

| Pop-up message (colour) | Frequency as a percentage of serialised products entered into the study (n=2188) |

| Authenticated (purple symbol requiring no action) | 96% |

| Already authenticated here (amber) | Naturally occurring* |

| Authenticated elsewhere/falsified (amber) | 1% |

| Product recalled (red) | 1% |

| Pack recalled (red) | 1% |

| Pack expired (red) | 1% |

*If a medicine were scanned twice, the second scan would generate a pop-up which stated that the medicine was ‘Already authenticated here'. Therefore, these alerts were ‘Naturally occurring’ and not introduced by the principal investigator.

Medicines with serialised stickers attached were recorded in a database maintained by the principal investigator (PI); these medicine packs were then compared with the medicines quarantined by NHS staff members and those recorded as scanned by the MA provider’s database. Not all medicines within the dispensary were serialised. This simulated initial FMD decommissioning in a live environment, that is, an environment which contains a mix of serialised and non-serialised medicines.

Comparability of studies

The methodologies used in the repeat study were identical to those in stage one of the Naughton et al 2016 study13 (medicine decommissioning performed by pharmacists and accuracy-checking technicians at the checking stage). However, the technology included an audio alert which sounded on the attempted authentication of a medicine requiring quarantine. The same portfolio of 30 medicine lines was used over an 8-week period and the participants were given the same presentation and demonstration of the authentication technology as per the study protocol. Despite the best efforts of the PI, there may have been some perceived differences between both studies and these are noted in table 2.

Table 2.

Potential differences between Naughton et al 201613 and the repeat study

| Naughton et al 201613 (stage one) | Repeat study | Considerations |

| No previous exposure to medicine authentication (MA) technology | Previous exposure to MA technology | Previous results have not identified an association between technology exposure and increased compliance. There was a greater than 1-year interval between the studies |

| Conducted as a service evaluation study | Conducted as a research study | The repeat study involved ethical approval and written consent |

| This study was proposed by the principal investigator | This study was based on a consensus improvement (audio alarm) suggested by the participants | Compliance may have been affected by the motivation to implement an idea that was suggested by the participants |

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in study design or data collection as the research question regarded health information technology within a hospital setting. In this study MA had limited impact on healthcare provision to patients.

Results

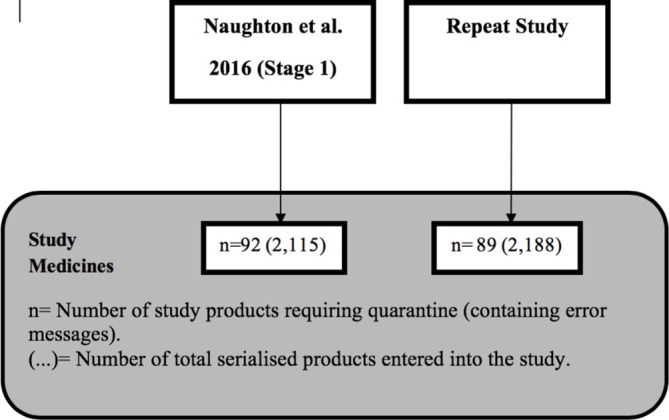

This repeat study involved a total of 2188 medicines and, of these, 89 generated a pop-up identifying the medicine as requiring quarantine (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A diagram identifying the total number of medicines included in both studies.

The EU FMD has mandated a maximum data round-trip (from scanning to external database and back) response time of less than 300 ms. Across both studies, this has been achieved with a quicker response time observed in the repeat study (table 3). Offline issues appear to have been more frequent in the repeat study with a 4.23% increase when compared with the unpublished data collected as part of the Naughton et al 2016 study13. The response times and frequency of offline issues recorded in Naughton et al 201613 and the repeat study are outlined in table 3 below.

Table 3.

The average response times and frequency of offline issues recorded in Naughton et al 201613 and the repeat study

| Parameter | Naughton et al 201613 | Repeat study | Expected standard |

| Medicine authentication (MA) technology average response times |

152 milliseconds (ms) (n=1604*) | 131 ms (n=2503*) | 300 ms |

| MA technology offline frequency |

0.44% (n=1604) | 4.67% (n=2503) | Undefined |

*These numbers represent total scans in each study which include decommissions, verifications, duplicate scans and re-commissioning.

The offline incidents and incorrect quarantine figures were extracted from unpublished data which was collected as part of the Naughton et al 2016 study.13

Incorrect quarantine

Incorrect quarantine was recorded in both studies. An incorrect quarantine occurs when a staff member quarantines a medicine that does not generate a pop-up alert. The number of incorrect quarantine incidents from the Naughton et al 201613 study and the repeat study are displayed in table 4. There were 11 cases in the 2016 study (of which three occurred during an offline period). However, there were 37 cases of incorrect quarantine in the repeat study (of which 17 occurred during an offline period) (table 4).

Table 4.

Incorrect quarantine

| Naughton et al 201613 | Repeat study | |

| Incorrect quarantine | 11 (of which three were during an offline episode) |

37 (of which 17 were during an offline episode) |

Workarounds

It was observed during this study that staff created workarounds. In instances where medicines would not scan due to an offline issue or otherwise, staff tended to quarantine the product. This workaround demonstrates that the staff erred on the side of caution when faced with offline incidents. It was also observed that after the staff had authenticated a product that was opened and partially used, they would use a pen to place a cross through the 2D data matrix to identify the part-pack medicine as authenticated.

Discussion

To knowingly introduce expired, recalled or potentially falsified medicine into the legitimate pharmaceutical supply chain would be disruptive, unethical and compromise patient safety. This study safely assessed the average response times, the frequency of incorrect quarantine and offline frequency in a controlled, operating closed-loop system without compromising patient safety and is, therefore, uniquely positioned. although, the addition of the audio alert did not appear to affect the technical parameters measured in this paper, that is, technology response times, false quarantine or offline instances. Further research is required to understand the effect of this user-instigated alteration on overall technology use and compliance.

MA has been researched in part in studies in Belgium where authentication of medicines has been commonplace.15 However, there is little evidence which identifies the technical performance of the approach beyond this study. Naughton et al 201613 and the repeat study refer to studies carried out in 2015 and 2016, respectively, and each was conducted over the same duration using the same 30 serialised medicines, which explains the similar number of products serialised in each study in figure 1.

Average response times

Medicine dispensing within a large university hospital occurs in stages. Broadly speaking, the prescription is clinically screened, labelled, dispensed and checked. An additional step, such as MA could have an impact on prescription processing operations and, more specifically, the prescription turn-around time. However, in this case, we identify that, on average, communication from a terminal to a national database will not necessarily be a rate-limiting step. Throughout the Naughton et al 201613 study and the present repeat study, average response times of 152 ms and 131 ms, respectively, were observed. These two studies provide evidence that the MA operation can be performed comfortably within the EU FMD limit of 300 ms which may reassure UK stakeholders. Although the response times in this study are positive, MA is not a microprocess which exists in isolation. Instead, it should be considered as an additional step which impacts adjacent processes. Therefore, the key to success is not a sub-300 ms response time but a well thought out reconsideration of current operations in the light of this additional step.

Workarounds

Work by Debono et al 16 explains that workarounds are employed to deliver service promptly and that localised workarounds affect other microsystems.16 It is important to be aware of and to report workarounds. Reporting ensures that ‘What is happening’ and ‘What should be happening’ are understood when making operational decisions which affect microsystems. Awareness of workarounds generating positive outcomes facilitates their incorporation into local policy and standard operating procedures (SOPs), while awareness of workarounds with negative outcomes facilitates their documentation and appropriate management. If a culture of reporting workarounds exists within a workplace, workarounds can be acknowledged and decisions regarding microsystems and related processes can be made based on a complete understanding of current practice.

Bypassing health information systems is common in the medical context17 and may become more common if digital healthcare systems are not responsibly designed. Kobayashi et al explain that ‘Workarounds are a common technique for dealing with the inherent uncertainty of dynamic work environments’.18 The introduction of MA technology and associated operations in the hospital pharmacy environment brings about this level of inherent uncertainty and, in this study this uncertainty has demonstrated a specific workaround which involves the crossing through of a 2D barcode rendering it unreadable, a new phenomenon which was observed consistently across the study. According to FMD regulations, a medicine pack requires decommissioning only once and subsequent supplies from the same pack do not require further verification which makes this workaround a useful approach. However, the destruction of the 2D data matrix removes the opportunity for the hospital to scan that barcode for other practices such as stock taking or medicine verification at the bedside. Hospitals may wish to consider what extra value, if any, beyond FMD compliance, they aim to achieve from serialised medicine packs before allowing or prohibiting a policy of striking through a 2D data matrix.

Incorrect quarantine and offline incidents

An effective diagnostic test relies on its sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity, or true positive rate, measures the proportion of positives identified as such by the test.19–21 Specificity, or true negative, reports the proportion of negatives that are correctly identified by the test.19–21 However, this approach is not entirely technical and relies on the interpretation of alerts from the user in a busy environment and the patience of staff to deal with offline issues. The MA technology was tested before use in each study and ad hoc testing was also performed by the PI, which aimed to identify instances of false negatives and ensure that medicines with preprogrammed alerts were being identified to the staff as such. False negatives were not identified during the testing period; therefore, the sensitivity and specificity were deemed to be 100% when the technology was online. However, there may have been cases where the technology gave no result, for example, during offline periods. The number of incidences of incorrect quarantine was compared with offline incidents and it is anticipated that the increase in offline issues resulted in multiple attempts to scan the same medicine which contributed to a higher number of scans in the repeat study (table 3). Staff observations and feedback identified that offline issues resulted in confusion, leading to a higher number of inappropriate product quarantines in the repeat study (n=37, of which 17 were during an offline episode). The effect of offline instances (when the scan from the terminal cannot communicate with the national database) on healthcare institutions may, therefore, cause a delay in the supply of medicines to patients. This study suggests that the increase in offline issues is responsible for the increased incorrect quarantine rate and confusion at the point of decommissioning which is likely to be augmented by inadequately designed information technology alerts. An option permitted by the FMD during an offline episode is to supply a medicine and manually enter the product details to evaluate the provenance of the product when online status resumes or halting medicine supply until the system is again online. Offline issues have a legal and practical impact. Supply without authentication from a professional, litigation perspective is not yet apparent; it is currently unclear what would happen in the instance where the technology is offline, resulting in the supply of an SF medicine. Considering there were 222 cases of substandard, recalled medicines and 11 cases of falsified medicine in the UK between 2001 and 2011, this scenario is likely to occur sooner rather than later.10 From a practical perspective, the offline issues seen in this study may result in the cessation of medicine dispensing until online MA processes resume for fear of dispensing an SF medicine. This may cause a delay in medicine supply and a backlog of dispensing in pharmacy departments. Pharmacy organisations are suggested to write SOPs which cover their stance on the supply of medicines during offline periods. Supply without decommissioning could result in a patient receiving an SF medicine, and withholding supply could delay patient treatment or hospital discharge.

This study was carried out using a technology provider that had been operating in Greece, Italy and Belgium for approximately 10 years. At the time, the offline issues experienced in this study were reported as having affected European clients also. This company is no longer in existence and national databases will be provided by other companies with less experience in this niche area. There is concern that this level of offline disruption may recur and mimic the disruption presented in this study on an international scale.

Conclusions and recommendations

Average response times below 300 ms are realistic and achievable under EU FMD conditions.13 Therefore, average response times should not undermine MA effectiveness. However, offline issues may be linked to incorrect quarantine and are likely to cause significant delays and confusion during offline periods. Hospitals and pharmacies are suggested to review their dispensing SOPs to include guidance regarding medicine dispensing operations during offline periods and record offline periods as a risk on their organisations risk registers. They could also mandate that their technology providers build in explicitly clear alerts that describe precisely what is required during offline periods and match those alerts with clear internal guidance, SOPs and training. Although this technological approach has proven its ability to operate at average response times well below the FMD mandated limit of 300 ms, it is suggested from this study that offline issues may have an effect on incorrect quarantine and that offline issues are likely to disrupt the delivery of medicines to patients. One way to reduce offline issues would be to penalise MA technology providers and the National Medicines Verification System (NMVS) provider for offline instances beyond an agreed contracted level. With appropriate incentives, these providers may be more likely to prioritise and rectify offline incidents.

It is important to be aware of the value of medicine serialisation and decide if an organisation wishes to grasp additional value or settle for the minimum level of legal compliance. It is also suggested that pharmacy regulatory bodies in countries with medicine serialisation legislation, should provide clear guidance concerning the sanctions associated with failure to decommission a medicine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge my mentors Professor Steve Chapman at Keele University and Professor Sue Dopson at the University of Oxford. I would like to acknowledge Dr Lindsey Roberts for her review and input into this publication. Finally I would like to thank Bhulesh Vadher for facilitating this study at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and the pharmacy department staff for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Twitter: @bernardnaughton

Contributors: BN was the principal investigator (PI) on this study, BN collected data, BN analysed the data and BN wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Keele University Internal Funds

Competing interests: BN is a consultant for Solfen Healthcare Limited and conducts consultancy which aims to generate impact from research.

Ethics approval: This study was classified as research according to NIHR guidelines. Keele University provided ethical approvals. Health Research Authority approvals and Trust R&D approvals were required and provided by both organisations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Please contact the corresponding author for access to original data.

Collaborators: Mr Bhulesh Vadher, Pharmacy Department, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

References

- 1. Research C for DE and. Drug Supply Chain Security Act - Title II of the Drug Quality and Security Act [Internet]. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugIntegrityandSupplyChainSecurity/DrugSupplyChainSecurityAct/ucm376829.htm (cited 24 Feb 2017).

- 2. European Medicines Agency - Human regulatory - Falsified medicines [Internet]. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/special_topics/general/general_content_000186.jsp (cited 20 Sep 2016).

- 3. Directive 2011/62/. EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 amending Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use, as regards the prevention of the entry into the legal supply chain of falsified medicinal productsText with EEA relevance - dir_2011_62_en.pdf [Internet. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2011_62/dir_2011_62_en.pdf (cited 9 Jun 2016).

- 4. WHO. Definitions of Substandard and Falsified (SF) Medical Products [Internet]. WHO. [ http://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/definitions/en/ (cited 2017 Jun 27). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newton PN, Hanson K, Goodman C. ACTwatch Group. Do anti-malarials in Africa meet quality standards? The market penetration of non quality-assured artemisinin combination therapy in eight African countries. Malar J 2017;16:204 10.1186/s12936-017-1818-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Newton PN, et al. . Poor-quality antimalarial drugs in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:488–96. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70064-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanif M, Mobarak MR, Ronan A, et al. . Fatal renal failure caused by diethylene glycol in paracetamol elixir: the Bangladesh epidemic. BMJ 1995;311:88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Renschler JP, Walters KM, Newton PN, et al. . Estimated under-five deaths associated with poor-quality antimalarials in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92(6 Suppl):119–26. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mackey TK, Cuomo R, Guerra C, et al. . After counterfeit Avastin®--what have we learned and what can be done? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015;12:302–8. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Almuzaini T, Sammons H, Choonara I. Substandard and falsified medicines in the UK: a retrospective review of drug alerts (2001-2011). BMJ Open 2013;3:e002924 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Union PO of the E. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/161 of 2 October 2015 supplementing Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council by laying down detailed rules for the safety features appearing on the packaging of medicinal products for human use (Text with EEA relevance) [Internet. 2015. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/645fa920-cef8-11e5-a4b5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (cited 19 Dec 2017).

- 12. Naughton BD, Smith JA, Brindley DA. Establishing good authentication practice (GAP) in secondary care to protect against falsified medicines and improve patient safety. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 2016;23:118–20. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2015-000750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naughton B, Roberts L, Dopson S, et al. . Effectiveness of medicines authentication technology to detect counterfeit, recalled and expired medicines: a two-stage quantitative secondary care study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013837 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naughton B, Roberts L, Dopson S, et al. . Medicine authentication technology as a counterfeit medicine-detection tool: a Delphi method study to establish expert opinion on manual medicine authentication technology in secondary care. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013838 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simoens S. Analysis of drug authentication at the point of dispensing in Belgian and Greek community pharmacies. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:1701–6. 10.1345/aph.1M215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Debono D, Greenfield D, Black D, et al. . Workarounds: straddling or widening gaps in the safe delivery of healthcare. In: Proceedings of 7th international conference in organisational behaviour in health care, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koppel R, Wetterneck T, Telles JL, et al. . Workarounds to barcode medication administration systems: their occurrences, causes, and threats to patient safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:408–23. 10.1197/jamia.M2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kobayashi M, Fussell SR, Xiao Y, et al. . Workflow, and Workarounds in a Medical Context. In: CHI’ 05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2005:1561–4. Available from http://doi.acm.org/ (cited 9 Aug 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lalkhen AG, McCluskey A. Clinical tests: sensitivity and specificity. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain 2008;8:221–3. 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkn041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests. 1: Sensitivity and specificity. BMJ 1994;308:1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akobeng AK. Understanding diagnostic tests 1: sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:338–41. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00180.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.