Abstract

Objective

To determine the presence and predictors of depression and anxiety in pet owners after a diagnosis of cancer in their pets.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

A veterinary medical centre specialised in oncology for dogs and cats and two primary veterinary clinics in Japan.

Participants

The participants for analysis were 99 owners of a pet with cancer diagnosis received in the past 1–3 weeks and 94 owners of a healthy pet.

Main outcome measures

Self-reported questionnaires were used to assess depression and anxiety. Depression was assessed using the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and anxiety was measured by using the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form JYZ.

Results

Depression scores were significantly higher in owners of a pet with cancer than owners of a healthy pet, even after adjustment for potential confounders (p<0.001). Within the owners of a pet with cancer, depression was significantly more common in those who were employed than those who were unemployed (p=0.048). State anxiety scores were significantly higher in owners of a pet with cancer than owners of a healthy pet, even after adjustment for potential confounders, including trait–anxiety scores (p<0.001). Furthermore, in owners of a pet with cancer, state anxiety was higher in owners with high trait anxiety (p<0.001) and in owners whose pets had a poor prognosis (p=0.027).

Conclusion

The results indicate that some owners tended to become depressed and anxious after their pets had received a diagnosis of cancer. Employment may be a predictor of depression. High trait anxiety and a pet with a poor prognosis may increase owners’ state anxiety. Including the pet in a family genogram and attention to the pet’s health condition may be important considerations for family practice.

Keywords: family practice, depression, anxiety, pet cancer, family genogram

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first report to investigate the psychological effects of a diagnosis of cancer in pets on owners.

This study is the interdisciplinary research between medicine and veterinary medicine, which has not been studied to date.

The study setting was limited to a referral secondary veterinary medical centre specialised in oncology, so the generalisability of the results is not clear.

Introduction

Since 1973, the birth rate in Japan has continued to decline.1 Meanwhile, a 2015 survey by the Japanese Pet Food Association determined that 19 791 000 dogs and cats are owned in Japan.2 Furthermore, this report found that 14.1% of families own dogs and 10.1% own cats; of these, 78.9% of dogs and 82.0% of cats are raised in the house. Thus, with the declining birth rate, ageing society and a decrease in the number of household members in Japan, it is thought that dogs and cats are becoming treated as companion animals, that is, family members.

Most pet owners regard their companion animals as family members.3 Companion animals often play an important role for individuals, couples and families, and animals that become important family members can make patients comfortable.4 Living with pets can have positive impacts on mental health, such as reducing the feeling of loneliness, depression and anxiety.5 6 Furthermore, companion animals can provide benefits to pet owners with mental health problems through the intensity of connectivity with pet owners.7 Conversely, pet ownership can also have negative effects on the management of mental health disorders, which relate to financial costs, housing situations and mental burden, especially if pets are unruly.8–11 Another negative aspect is the mourning after the loss of a domestic pet.12–14 Furthermore, caregiver burden in owners of a pet with chronic or terminal disease has been reported.15

The roles and responsibilities of family members of human patients with cancer are significant because families are required to support and care for the patient and deal with social problems. Thus, family members can often feel a great burden. A survey of families of human patients with leukaemia found that depression, measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), was higher than the healthy level.16 Another study of families of human cancer patients found that physical symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social activity disorders and depression tendency, measured by the General Health Questionnaire Mental Health Survey, were also above healthy levels.17 In particular, parents of childhood cancer patients experience high levels of anxiety and depression after receiving the diagnosis,18 although their poor mental state may be alleviated by psychosocial support.19

Improvement in veterinary medical care techniques in recent years means that companion animals live longer, and the majority of dogs now die from cancer.20 Studies conducted in the UK and Japan reported that the most common cause of death in dogs was cancer.21–23 Therefore, there is a high likelihood that pet owners will at some point receive a diagnosis of cancer in their pets. However, no study has investigated whether pet owners experience depression or anxiety after such a diagnosis.

The aim of this study was to examine the psychological effects of a cancer diagnosis in pets on pet owners. We therefore investigated the presence of anxiety and depression after diagnosis and explored their predictors. Our hypothesis was that owners of a dog or a cat diagnosed with cancer suffer from depression and anxiety that is similar to that experienced by family members of human cancer patients.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

The study design was a cross-sectional survey. Anxiety and depression scores in owners of a pet diagnosed with cancer were compared with those of owners of a healthy pet. The survey was conducted between August 2013 and November 2016 at three veterinary clinics in Japan. Owners of a pet with cancer were recruited from the Japan Small Animal Cancer Center (JSACC) and owners of a healthy pet were recruited from the Minamino Veterinary Clinic and Aster Animal Hospital. JSACC is a referral veterinary medical centre specialised in oncology for dogs and cats located in Tokorozawa City, Saitama Prefecture, next to Tokyo. A psychological counsellor with a veterinarian license (AN) interviewed the pet owners at their first visit to the JSACC. The Minamino Veterinary Clinic and Aster Animal Hospital are primary veterinary clinics. When dogs and cats are diagnosed with cancer or suspected to have cancer at these two clinics, their owners can receive a referral to the JSACC if they wish. The Minamino Veterinary Clinic is located in Hachioji, Tokyo, and the Aster Animal Hospital is in Kawaguchi City, Saitama Prefecture, and they are located approximately 25 km and 20 km from the JSACC, respectively. This study was designed and reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.24

Participants

Owners of a pet with cancer

Pet owners were asked to participate in the study 1–3 weeks after their pets had received a cancer diagnosis at the JSACC. As a procedure, we set in advance the survey date when the counsellor/veterinarian (AN) or veterinarian (YN) could investigate without affecting daily veterinary practice, depending on the number of patients reserved. Owners of a pet with cancer were consecutively recruited on the survey date. YN and AN informed the owners of a pet with cancer of the purpose and methods of the study and assured them that their privacy would be protected and that they would not be disadvantaged if they did not agree to participate. Those who agreed to participate provided signed consent. Questionnaires were completed by the pet owners and collected in an envelope. All personal information was anonymised and questionnaires were labelled with an identification code.

The attending veterinarian predicted the survival time, and, for ethical reasons, cases in which the pet was unlikely to survive for more than a week were excluded. Namely, we considered it too invasive for owners notified of imminent death of their pets to be asked to participate.

Owners of a healthy pet

Pet owners who visited the Minamino Veterinary Clinic or Aster Animal Hospital for preventive medicines such as vaccination, heartworm prevention or health promotion were asked to participate in the study on days when the survey could be conducted. The participants were intermittently recruited at both veterinary clinics as a convenient sample. Pet owners that agreed to take part in the survey were provided with details of the research in a written document. Completion of the questionnaire was considered as consent to participate in the study. Questionnaires were collected in an envelope in the same way as for owners of a pet with cancer.

Owners whose dog or cat had suffered from malignant tumour in the past or were currently suffering from malignant tumour were excluded. We also excluded owners whose pet had a disease that was deemed to be severe or life threatening by the attending veterinarian, which could have affected the psychological state of pet owners.

In both groups, pet owners were over 20 years old.

Measurement and variables

Main outcome: depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Japanese version of the CES-D.25 CES-D is a self-report questionnaire developed by the National Institute of Mental Health for the purposes of identifying depressive disorder in people aged over 15 years.26 The frequency of depressive symptoms in the week before the examination was assessed by 20 items. In scoring the CES-D, a value of 0, 1, 2 or 3 was assigned to the answer depending on whether the item had a positive or negative context. Total scores range from 0 to 60 and higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. CES-D score of 16 or higher was considered to indicate probable depression.25 26

CES-D questionnaires that contained more than five items with missing data were excluded from the data analysis. If the number of unanswered items was four items or less, the average value of the answered items was assigned to the missing items.

Main outcome: state anxiety

Anxiety was assessed using the Japanese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form JYZ (STAI-JYZ).27 STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures anxiety as an emotional state (state anxiety) and as individual characteristics (trait anxiety).28 It consists of 40 questions with 20 items per category and scores range from 20 to 80. Responses are given on a four-point Likert scale. State anxiety items measure the respondent’s anxiety level over the past 2 weeks, whereas trait anxiety items measure the respondent’s characteristic anxiety level. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety. The state- anxiety score is classified into five grades (20≤35= very low, 35≤45= low, 45≤55= moderate, 55≤65= high, 65–80=very high). Respondents who scored over 55 were defined as the high anxiety group.27 28

Missing responses to the 20 questions used to calculate the state anxiety scores in the STAI questionnaire were dealt with in two ways, as follows: (1) the questionnaire was excluded from the data analysis; and (2) missing responses were assigned a score of 1 (low anxiety) for owners of a pet with cancer and 4 (high anxiety) for owners of a healthy pet.

Predictor variables: characteristics of participants and pets

Age, gender, employment (employed or unemployed), animal species (dog or cat), caregiver (main or not main), number of people per household, number of animals per household and bereavement experience with pets were obtained from a self-report questionnaire for all participants. ‘Employed’ included either full-time or part-time workers. ‘Unemployed’ also included retired persons, full-time housewives, those without an occupation and those with temporary leave from their job.

The owners of a pet with cancer were also asked about the pet’s prognosis (curable, survival for more than a year, from a few months to less than a year or several weeks) and presence of pet’s symptoms (anorexia, pain and neurological conditions including convulsion and respiratory distress).

Study size

Based on the hypothesis that pet owners have high levels of depression and state anxiety after their pets had received a diagnosis of cancer, the number of participants required was calculated in advance. Assuming state anxiety scores of 50 and 40 for owners of a pet with cancer and owners with a healthy pet, respectively, both each with an SD of 11, we calculated the number of participants required to identify a statistically significant difference as 26 in each group (α=0.05, β=0.10). In a multiple regression model, 20 samples are required for one variable.29 This study included nine explanatory variables, so 180 participants were required.

Analysis and statistical methods

For comparisons in demographic characteristics between owners of a pet with cancer and owners of a healthy pet, Student’s t - test for parametric data or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-parametric data was used for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables.

Student’s t-test was used for between-group comparisons of parametric CES-D score and state and trait anxiety (STAI) scores and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for between-group comparisons of non-parametric CES-D score and state and trait anxiety (STAI) scores. Fisher’s exact test was used for between-group comparisons of the proportion of participants with a CES-D score of 16 or more for depression and the proportion of those with a STAI score of 55 or more for state anxiety.

Model 1: To evaluate the independent effects of cancer diagnosis on the CES-D (model 1-CES-D) and state anxiety (model 1-STAI) scores, the regression model included gender, age, employment, animal species (dog or cat), caregiver, number of people/animals per household, bereavement experience with pets and trait anxiety (model 1-STAI only) as potential confounders. The variance inflation factor was calculated to check multicollinearity.

Model 2: To identify factors associated with the CES-D (model 2-CESD) and state anxiety (model 2-STAI) scores in owners of a pet with cancer, the regression model included pet’s prognosis (life expectancy from a few months to less than a year, or several weeks), presence of clinical symptoms and factors that had a p value of less than 0.2 in model 1.

A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA/SE V.13.30

Ethical considerations

The research protocol was approved. A psychological counsellor with a veterinarian license (AN) interviewed the pet owners at their first visit to the JSACC. In owners of a pet with cancer, counselling and/or medical consultation were supposed to be recommended for owners with high levels of depression and anxiety which were based on an attending veterinarian’s decision at consultation.

Patient and public involvement

No participants were involved in the development of the research question, outcome measures or design or implementation of the study. No participants were involved in the analysis or write up of the study. There are no plans to disseminate our overall results to the study participants.

Results

Participants

The questionnaires from 100 owners of a pet with cancer and 100 owners of a healthy pet were obtained. One owner of a pet with cancer was excluded for analysis due to missing data of some demographic variables. Six owners of a healthy pet were excluded for analysis due to the presence of past cancer history of pet (n=2), no information on past cancer history of pet (n=2), no response to CES-D/STAI (n=1) or exclusion criteria of age (n=1, we asked the mother to respond to questionnaires: however, her son responded). Data from a total of 193 participants were analysed (99 owners of a pet with cancer and 94 owners of a healthy pet). The participants’ characteristics are shown in table 1. Except for the number of animals per household, there were no significant differences between the two groups in demographic variables as shown in table 1. The median period between notification of the cancer diagnosis and completion of the questionnaire survey in the owners of a pet with cancer was 14 days (range, 7–21 days).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Owners of a pet with cancer | Owners of a healthy pet | P value | |

| Number of participants | 99 | 94 | |

| Age, mean (range), year | 48.9 (21–75) | 46.5 (22–70) | 0.144 |

| Gender | |||

| Male, no. (%) | 26 (26.3) | 15 (16.0) | 0.112 |

| Female, no. (%) | 73 (73.7) | 79 (84.0) | |

| Animal species | |||

| Dog, no. (%) | 83 (83.8) | 84 (89.4) | 0.297 |

| Cat, no. (%) | 16 (16.2) | 10 (10.6) | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed, no. (%) | 68 (68.7) | 67 (71.3) | 0.754 |

| Unemployed, no. (%) | 31 (31.3) | 27 (28.7) | |

| Caregiver | |||

| Main caregiver, no. (%) | 83 (83.8) | 84 (89.4) | 0.297 |

| Not main caregiver, no. (%) | 16 (16.2) | 10 (10.6) | |

| Number of people per household | |||

| 1, no. (%) | 7 (7.1) | 5 (5.3) | 0.768 |

| 2+, no. (%) | 92 (92.9) | 89 (94.7) | |

| Number of animals per household, | |||

| 1, no. (%) | 57 (57.6) | 69 (73.4) | 0.024 |

| 2+, no. (%) | 42 (42.4) | 25 (26.6) | |

| Bereavement experience with pets | |||

| Yes, no. (%) | 76 (76.8) | 68 (72.3) | 0.511 |

Student’s t-test was used for comparison in age between two groups.

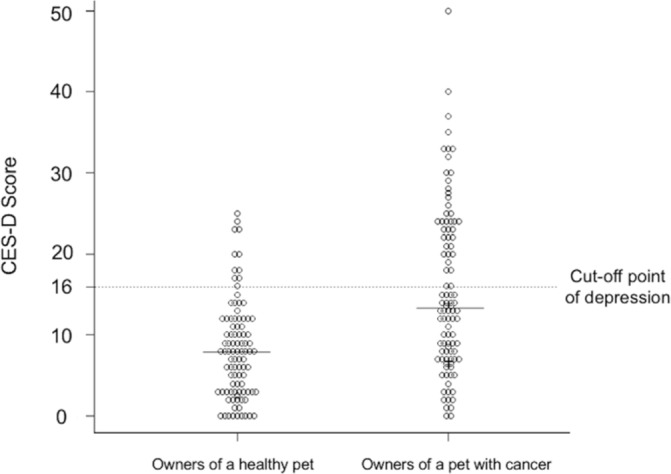

Depression

Figure 1 shows the CES-D scores of the two groups. The median CES-D score was 13.34 (25–75 percentile: 7–23) in the owners of a pet with cancer (n=98) and 8 (25–75 percentile: 3–12) in the owners of a healthy pet (n=94). The distribution of the two groups was significantly different (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: p<0.001). In addition, 39.8% (39/98) of the owners of a pet with cancer scored 16 or higher on the CES-D, which was significantly higher than the proportion in the owners of a healthy pet (11.7% (11/94), Fisher’s exact test: p<0.001). In the multiple regression analysis (model 1-CES-D), CES-D scores were significantly higher in the owners of a pet with cancer even after adjustment for potential confounders (p<0.001, table 2). Among the owners of a pet with cancer, owners who were employed had significantly higher depression scores than those who were unemployed (model 2-CES-D) (p=0.048, table 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) scores in the owners of a health pet and the owners of a pet with cancer. The solid line shows the median CES-D score in each group. The dotted line shows the cut-off point for depression.

Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) scores (model 1-CES-D)

| Coefficient | (95% CI) | P value | |

| Pet with cancer | 7.948 | (5.493 to 10.403) | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.038 | (−0.149 to 0.072) | 0.495 |

| Female | 2.601 | (−0.722 to 5.925) | 0.124 |

| Dog | 1.577 | (−2.034 to 5.188) | 0.390 |

| Employed | 3.045 | (0.310 to 5.779) | 0.029 |

| Main caregiver | −0.786 | (−4.663 to 3.091) | 0.690 |

| 2+ persons per household | 0.980 | (−4.113 to 6.074) | 0.705 |

| 2+ animals per household | −1.246 | (−3.911 to 1.418) | 0.357 |

| Bereavement of a pet | −0.674 | (−3.522 to 2.172) | 0.641 |

Table 3.

Analysis of predictors associated with depression among the cancer group (model 2-Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale)

| Coefficient | (95% CI) | P value | |

| Female | 3.799 | (−0.602 to 8.200) | 0.090 |

| Employed | 4.224 | (0.029 to 8.419) | 0.048 |

| Prognosis | 3.499 | (−0.446 to 7.445) | 0.081 |

| Symptoms | −0.927 | (−4.993 to 3.139) | 0.652 |

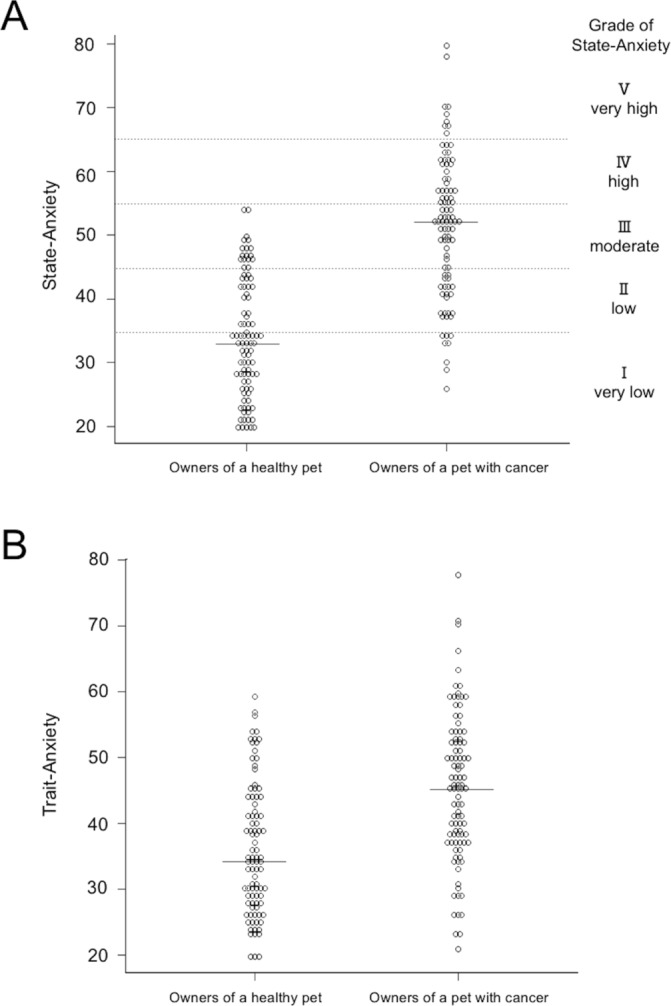

State anxiety (STAI scores)

The state anxiety and trait anxiety scores of the two groups are shown in figure 2A,B. For the cases in which all 20 questions for state anxiety were answered, the median state anxiety score was 52 (25–75 percentile: 43–59) in the owners of a pet with cancer (n=93) and 33 (25–75 percentile: 27–42) in the owners of a healthy pet (n=91). The distribution of the two groups was significantly different (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: p<0.001). The proportion of owners with levels of high anxiety in the owners of a pet with cancer was 39.8% (37/93), which was significantly higher than 0% (0/91) in the owners of a healthy pet (Fisher’s exact test: p<0.001). Similarly, when missing values were imputed, the median state anxiety score was 52 (25–75 percentile: 43–58) in the owners of a pet with cancer (n=98), which was significantly higher than 33.5 (25–75 percentile: 27–42) in the owners of a healthy pet (n=92) (p<0.001). The median trait anxiety score was 45 (25–75 percentile: 37–52.5) in the owners of a pet with cancer (n=96) and 34.5 (25–75 percentile: 27–42) in the owners of a healthy pet (n=90). The distribution of the two groups was significantly different (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Distribution of state anxiety (A) and trait anxiety (B) scores in the owners of a healthy pet and the owners of a pet with cancer. The solid lines show the median anxiety score in each group. (A) The median state anxiety score was moderate in the owners of a pet with cancer, but very low in the owners of a healthy pet. (B) The median trait anxiety score in the owners of a pet with cancer was higher than in the owners of a healthy pet.

In the multiple regression model, after adjustment for potential confounders including trait anxiety scores, state anxiety scores were significantly higher in the owners of a pet with cancer than in owners of a healthy pet (model 1-STAI) (p<0.001, table 4). Furthermore, in the owners of a pet with cancer, state anxiety scores were higher in owners with high trait anxiety (p<0.001) and in those with pets with a life expectancy of several months (model 2-STAI) (p=0.027, table 5).

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of state anxiety scores (model 1-State–Trait Anxiety Inventory)

| Coefficient | (95% CI) | P value | |

| Pet with cancer | 11.056 | (8.510 to 13.601) | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.043 | (−0.148 to 0.060) | 0.409 |

| Female | −0.511 | (−3.544 to 2.522) | 0.740 |

| Dog | −0.849 | (−4.160 to 2.461) | 0.613 |

| Employed | 1.495 | (−1.041 to 4.032) | 0.246 |

| Main caregiver | −0.387 | (−3.939 to 3.164) | 0.830 |

| 2+ persons per household | 3.676 | (−0.886 to 8.238) | 0.114 |

| 2+ animals per household | 0.463 | (−2.050 to 2.976) | 0.717 |

| Bereavement of a pet | 1.388 | (−1.216 to 3.993) | 0.294 |

| Trait anxiety | 0.654 | (0.546 to 0.761) | <0.001 |

Table 5.

Analysis of predictors associated with state anxiety within the cancer group (model 2-State–Trait Anxiety Inventory)

| Coefficient | (95% CI) | P value | |

| 2+ persons per household | 3.614 | (−3.089 to 10.319) | 0.287 |

| Trait anxiety | 0.570 | (0.405 to 0.734) | <0.001 |

| Prognosis | 4.318 | (0.508 to 8.128) | 0.027 |

| Symptoms | 3.307 | (−0.543 to 7.157) | 0.091 |

Discussion

The present study revealed high levels of anxiety and depression among owners of pets that had received a diagnosis of cancer. Within the owners of a pet with cancer, depression was significantly more common in those who were employed than those who were unemployed. The state anxiety was higher in owners with high trait anxiety and in owners of a pet with a poor prognosis. This is the first report to investigate the psychological effects of pet cancer on their owners.

After being notified that their dog or cat had cancer, 39.8% of owners reported symptoms of depression. Two previous studies that investigated depression among family members of patients with cancer using the CES-D found that 52.9% and 66.4% of families reported symptoms of depression, respectively.31 32 Although pet owners were less likely to suffer depression than the family members of cancer patients, almost 40% were affected.

Owners who were employed were more likely to report depression symptoms than those who were unemployed. Insufficient time available to care for their pets and visit a veterinary clinic due to working hours may have led to a sense of guilt. This feeling is likely similar to guilt felt when a pet owner with mental health problems cannot manage unruly pets.8–11 Furthermore, a previous study reported that the median CES-D score of owners of a pet with chronic or terminal diseases was 19.87,15 which was higher than the median of 13.34 in this study, which was measured 1–3 weeks after the notification of pet cancer. Owners’ depression may be sustained or increased by the need to provide long-term nursing care for their pets. Therefore, psychosocial support from the early stage after notification is necessary so that these owners do not develop maladjustment or mood disorder.

The median state anxiety score among owners of a pet with cancer was 52, which was significantly higher than the median of 33.5 among owners of a healthy pet. Studies that have used STAI to measure anxiety in parents of children diagnosed with cancer reported average state anxiety scores of 56.7 and 52.7 for mothers and fathers, respectively.33 The similarity in the state anxiety scores of owners of a pet with cancer suggests that dogs and cats may play a role as a member of the family. The high anxiety in owners of a pet with cancer could have been caused by the cost of treatment, the burden of taking the pet to the clinic, providing nursing care, anxiety about death of a pet and deterioration of clinical symptoms such as changes in the pet’s appearance or increased pain.

In this study, anxiety was higher among owners who had a pet with a poor prognosis; that is, with a life expectancy from several weeks to less than a year, which suggests that anxiety increases as the prospect of bereavement becomes more immediate. Furthermore, owners with high trait anxiety were more likely to suffer from state anxiety than owners with low trait anxiety. A previous study revealed that cancer patients with high trait anxiety experience stronger psychological distress such as tension and anxiety after a diagnosis of cancer than patients with low trait anxiety.34 Therefore, trait anxiety may be one factor that affects the state anxiety of owners when their pets are diagnosed with cancer. Moreover, trait anxiety scores in owners of a pet with cancer were significantly higher than those in owners of a healthy pet (45 vs 34.5, p<0.001). Although trait anxiety, a personality trait that tends to cause anxiety, is relatively stable, the high trait anxiety seen in owners of a pet with cancer may have been caused by the state anxiety induced by their pet’s cancer diagnosis.

The results of our study are consistent with the idea that companion animals are regarded as important family members, as found by previous studies3 4 35 because there is similarity between the degree of anxiety after notification of pet cancer and that of human cancer. Barker et al reported that the relationships between typical pet owners/dog enthusiasts and companion dogs were similar to relationships with a spouse, child and parents; this research measured the distance between pet owners and pets, and owners and family members, using the Family Life Space Diagram.35 Furthermore, previous studies have noted that pets should be included in the family genogram.36 37 Including pets in a family genogram may be useful for medical treatment in family-oriented care by family physicians. Therefore, we propose that the following information about companion animals should be entered into the family genogram: name, age, animal species, current medical history, animal’s prognosis and relationship with the family. Family physicians should pay attention to the health condition of companion animals. In addition, family physicians should recognise the social environment of pet owners, such as employment status. It is important not only for family physicians but also for psychiatrists to consider the possibility that owners of a pet with cancer may be suffering from depression and anxiety and may need mental healthcare. Our study is the first attempt to describe the psychological impact such as depression and anxiety on the pet owners after notification of pet cancer. This information is necessary for family physicians who see a patient with depressive and/or anxiety feelings as the first encounter. Also, this is an important message for veterinarians because they should pay more attention to tell the bad news more carefully and consider the impact on pet owners.

One limitation of this study is the generalisability of results because the study setting was limited to a referral secondary veterinary medical centre specialised in oncology in an urban area. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that originally enthusiastic owners and owners with a tendency toward depression and high trait anxiety were more likely to visit the referral veterinary medical centre. The proportion of pet owners with depression and anxiety may be lower than that identified in the present study when conducting surveys in all area of Japan, including the countryside, and surveys conducted at a primary care clinic. Second, while our results are valid in Japanese culture, they remain to be replicated in other cultures. Similar results may be obtained in countries in which pets are treated as family members. Third, we used convenience sampling rather than consecutive sampling, which may have led to a selection bias. In addition, because a screening test for depression was used in this study, it was uncertain whether the participants had developed an actual mental disorder. The progression of depression and anxiety over the long term is also unknown, as the investigation took place 1–3 weeks after notification of the diagnosis. The detailed processes that cause depression and anxiety may be elucidated by investigating depression and anxiety in owners of a pet diagnosed with cancer at primary veterinary clinics and monitoring them over time. Interventions such as counselling for pet owners after notification of a cancer diagnosis should also be considered.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that some owners tended to become depressed and anxious after their pets had received a diagnosis of cancer. Owners who were employed had a higher rate of depression than those who were unemployed, and state anxiety was higher in owners with high trait anxiety and in those whose pets had a poor prognosis. Physicians may find it helpful to include pets in the family genogram and to consider the pets’ health condition when providing medical treatment in family practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Masamine Takanosu, Nasunogahara Veterinary Clinic, for his kind advice and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr Takuto Segawa, Dr Ryoko Yamato and Dr Satomi Kajiwara for collecting the data. We are grateful to the pet owners who participated in this study. Finally, I (YN) would like to express my gratitude to my family for their warm encouragement.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: YN conceived and designed the study, analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. MM contributed to the conception and design of the study and analysis and interpretation of the data. AN, JH and EM contributed to the conception of the study and acquisition of the data. HW, SY, HI, MK, RM, YS and EY contributed to the interpretation of the data and discussions to help draft the manuscript. TK contributed to the conception of the study. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for the accuracy of the work. YN is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant for post-graduate students from Jikei University School of Medicine.

Disclaimer: The study sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, writing the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: MM received a lecture fee from the Japan Small Animal Medical Center, MM is an adviser of the Centre for Family Medicine Development practice-based research network, MM received a lecture fee and lecture travel fee from the Centre for Family Medicine Development, MM received a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and MM is a Program Director of the Jikei Clinical Research Program for Primary-care.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee of The Jikei University School of Medicine approved study protocols (Ethics number:25-049 7184).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Live births specified on report of vital statistics in FY2010. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/FY2010/live_births.html (accessed 18 Oct 2018).

- 2. Japan Pet Food Association. Industry’s annual national pet owner survey, 2015. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen SP. Can pets function as family members? West J Nurs Res 2002;24:621–38. 10.1177/019394502320555386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walsh F. Human-animal bonds I: the relational significance of companion animals. Fam Process 2009;48:462–80. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zasloff RL, Kidd AH. Loneliness and pet ownership among single women. Psychol Rep 1994;75:747–52. 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.2.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fritz CL, Farver TB, Hart LA, et al. . Companion animals and the psychological health of Alzheimer patients' caregivers. Psychol Rep 1996;78:467–81. 10.2466/pr0.1996.78.2.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brooks HL, Rushton K, Lovell K, et al. . The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:31 10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brooks H, Rushton K, Walker S, et al. . Ontological security and connectivity provided by pets: a study in the self-management of the everyday lives of people diagnosed with a long-term mental health condition. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:409 10.1186/s12888-016-1111-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wells DL. Associations between pet ownership and self-reported health status in people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:407–13. 10.1089/acm.2008.0496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zimolag Ulrike (Uli), Krupa T. The occupation of pet ownership as an enabler of community integration in serious mental illness: a single exploratory case study. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 2010;26:176–96. 10.1080/01642121003736101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zimolag U, Krupa T. Pet ownership as a meaningful community occupation for people with serious mental illness. Am J Occup Ther 2009;63:126–37. 10.5014/ajot.63.2.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keddie KM. Pathological mourning after the death of a domestic pet. Br J Psychiatry 1977;131:21–5. 10.1192/bjp.131.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wrobel TA, Dye AL. Grieving pet death: normative, gender, and attachment issues. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying 2003;47:385–93. 10.2190/QYV5-LLJ1-T043-U0F9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams CL, Bonnett BN, Meek AH. Predictors of owner response to companion animal death in 177 clients from 14 practices in Ontario. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;217:1303–9. 10.2460/javma.2000.217.1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spitznagel MB, Jacobson DM, Cox MD, et al. . Caregiver burden in owners of a sick companion animal: a cross-sectional observational study. Vet Rec 2017;181:321 10.1136/vr.104295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shapiro J, Perez M, Warden MJ. The importance of family functioning to caregiver adaptation in mothers of child cancer patients: testing a social ecological model. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 1998;15:47–54. 10.1177/104345429801500107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Payne S, Smith P, Dean S. Identifying the concerns of informal carers in palliative care. Palliat Med 1999;13:37–44. 10.1191/026921699673763725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sawyer M, Antoniou G, Toogood I, et al. . Childhood cancer: a 4-year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2000;22:214–20. 10.1097/00043426-200005000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerhardt CA, Compas BE, Connor JK, et al. . Association of a mixed anxiety-depression syndrome and symptoms of major depressive disorder during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 1999;28:305–23. 10.1023/A:1021632910823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fleming JM, Creevy KE, Promislow DE. Mortality in north american dogs from 1984 to 2004: an investigation into age-, size-, and breed-related causes of death. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:187–98. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adams VJ, Evans KM, Sampson J, et al. . Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 2010;51:512–24. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00974.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Neill DG, Church DB, McGreevy PD, et al. . Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England. Vet J 2013;198:638–43. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Inoue M, Hasegawa A, Hosoi Y, et al. . A current life table and causes of death for insured dogs in Japan. Prev Vet Med 2015;120:210–8. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies. http://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/STROBE_checklist_v4_cross-sectional.pdf (accessed 18 Oct 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Shima S, Shikano T, Kitamura T, et al. . New self-rating scales for depression. Clinical Psychiatry 1985;27:717–23. in Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hidano N, Fukuhara M, Iwawaki M, et al. . Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory-form JYZ. Jitsumu Kyoiku-Shuppan 2000. in Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. STAI manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory ("self-evaluation questionnaire"). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feinstein AR. Multivariable Analysis: An Introduction. New Heaven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13: College Station, StataCorp LP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carter PA, Chang BL. Sleep and depression in cancer caregivers. Cancer Nurs 2000;23:410–5. 10.1097/00002820-200012000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H. Exploring the other side of cancer care: the informal caregiver. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2009;13:128–36. 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dahlquist LM, Czyzewski DI, Copeland KG, et al. . Parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer: anxiety, coping, and marital distress. J Pediatr Psychol 1993;18:365–76. 10.1093/jpepsy/18.3.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ando N, Iwamitsu Y, Kuranami M, et al. . Psychological characteristics and subjective symptoms as determinants of psychological distress in patients prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:1361–70. 10.1007/s00520-009-0593-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barker SB, Barker RT, Dawson KS, et al. . The use of the family life space diagram in establishing interconnectedness: a preliminary study of sexual abuse survivors, their significant others, and pets. Individual Psychology 1997;53:435–50. [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGoldrick M, Gerson R, Petry S. Genograms: assessment and intervention. 3 edn New York: WW Norton & Company, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walsh F. Human-animal bonds II: the role of pets in family systems and family therapy. Fam Process 2009;48:481–99. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.