Abstract

Background: Pressure injuries negatively impact quality of life and participation for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI). Objective: To examine the factors that may protect against the development of medically serious pressure injuries in adults with SCI. Methods: A qualitative analysis was conducted using treatment notes regarding 50 socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals who did not develop medically serious pressure injuries during a 12-month pressure injury prevention intervention program. Results: Eight types of potentially protective factors were identified: meaningful activity, motivation to prevent negative health outcomes, stability/resources, equipment, communication and self-advocacy skills, personal traits, physical factors, and behaviors/activities. Conclusions: Some protective factors (eg, personal traits) may be inherent to certain individuals and nonmodifiable. However, future interventions for this population may benefit from a focus on acquisition of medical equipment and facilitation of sustainable, health-promoting habits and routines. Substantive policy changes may be necessary to facilitate access to adequate resources, particularly housing and equipment, for socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals with SCI. Further research is needed to understand the complex interplay of risk and protective factors for pressure injuries in adults with SCI, particularly in underserved groups.

Keywords: occupational therapy, pressure injuries, spinal cord injury

Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) must often contend with the development of pressure injuries for many years following discharge from acute rehabilitation.1 Pressure injuries develop when circulation is impeded—most frequently over bony prominences such as the sacrum, ischium, trochanters, and heels —and are classified based on the depth of tissue damage.2 The most severe, stages 3 and 4, also known as “medically serious” pressure injuries, carry devastating physical consequences, including muscle destruction, bone and ligament damage, tissue necrosis, and sepsis.3 Furthermore, severe pressure injuries remain one of the most common and costly reasons for unplanned hospitalizations among individuals with SCI.4–6 In addition to being life-threatening, pressure injuries can limit participation and negatively impact quality of life.7–9

Numerous risk factors for pressure injuries among adults with SCI have been identified; however, no behavioral interventions to date have demonstrated efficacy in reducing the incidence of pressure injuries.10–12 Yet, certain individuals with SCI exhibit multiple risk factors but successfully avoid pressure injuries over long periods of time. Prior research on factors that protect against pressure injuries is limited. Studies have identified maintenance of a healthy weight, diet, exercise, being married, having a college degree, and employment as protective against pressure injuries.13,14

The purpose of the present study was to identify and describe factors that may protect against the incidence of pressure injuries in individuals with SCI, particularly among racially/ethnically diverse adults of low socioeconomic status. We performed a secondary analysis of data from the Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study (PUPS). PUPS was a single-site, single-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared the Pressure Ulcer Prevention Program (PUPP), a lifestyle-based intervention delivered by licensed occupational therapists (OTs), to usual care. The methods and results of the RCT are described elsewhere.15,16 The difference in pressure injury incidence between intervention and control groups was not statistically significant in the intent-to-treat analysis.15

The PUPS participants were recruited from Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, which primarily serves a low-income, minority segment of Los Angeles County residents—one of the most medically underserved populations in the United States. All PUPS participants had a history of at least one medically serious pressure injury in the past 5 years. Pressure injuries are staged 1 to 4 based on the degree of bodily damage, with those that are most severe classified as stage 3 or 4 and deemed “medically serious.” Most participants had monthly incomes of less than $1,000 and multiple comorbid conditions. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between participants in the intervention arm who did and did not develop pressure injuries during the study (Table 1). Moreover, the intervention group was similar to the control group on all measures. This secondary analysis was initiated to identify other both modifiable and nonmodifiable qualities that may have served as protective factors in people with SCI. We were particularly interested in describing those protective factors that may not have been captured sufficiently by the parent study's quantitative measures.

Table 1.

Demographics of PUPP participants in intervention arm, comparing participants who developed at least one medically serious pressure ulcer to those who did not develop medically serious pressure ulcers during the intervention

| Demographics | Participants who did not develop any medically serious pressure injuries during PUPP intervention (n = 50) | Participants who developed at least one medically serious pressure injury during PUPP intervention (n = 25) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age, years | 41.3 (12.5) | 43.2 (13.2) | .54 |

| Race/ethnicity | .46 | ||

| White | 5 (10) | 5 (20) | |

| Black | 13 (26) | 8 (32) | |

| Hispanic | 26 (52) | 11 (44) | |

| Other | 6 (12) | 1 (4) | |

| Household income, US$ | .07 | ||

| 0–999 | 23 (46) | 15 (63) | |

| 1000–1900 | 16 (32) | 2 (8) | |

| 2000+ | 10 (20) | 7 (29) | |

| Education | .58 | ||

| <High school | 14 (28) | 11 (44) | |

| High school or GED | 13 (26) | 6 (24) | |

| Some college or trade | 17 (34) | 6 (24) | |

| College graduate | 6 (12) | 2 (8) | |

| Diabetes | 8 (17) | 8 (32) | .15 |

| No. of comorbidities | .12 | ||

| ≤6 | 36 (72) | 12 (48) | |

| >6 | 14 (28) | 13 (52) | |

| Language | 1.00 | ||

| English | 41 (72) | 21 (84) | |

| Spanish | 9 (18) | 4(16) | |

Note: PUPP = Pressure Ulcer Prevention Program.

*Independent samples t test for age; Fisher exact test for all other variables.

Methods

Intervention treatment notes were used as the data source for this analysis. We selected the subset of participants in the intervention arm of PUPS who had not acquired a pressure injury during the study period. Only participants in the treatment arm could be included in this analysis because there were no study-related treatment notes for the control condition. Fifty of the 82 participants who had been randomized to the PUPS treatment arm (1) did not incur a stage 3 or 4 pressure injury during the 12-month intervention and (2) participated in at least 4 intervention sessions to ensure an adequate intervention dose.

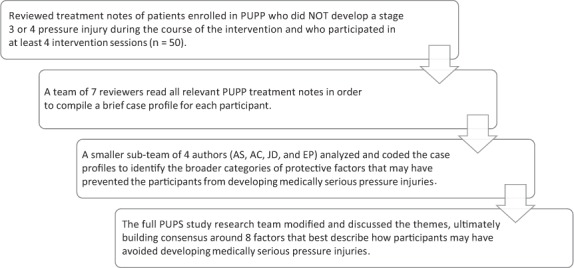

A team of seven OT researchers reviewed treatment notes on each eligible participant that were recorded by OT interveners during the intervention phase. All team members had prior training and experience in qualitative research methods and had been involved in the parent study. No members of this team had served as interveners in PUPS. No qualitative data were collected directly from the PUPS participants, nor were OT interveners asked to identify protective factors specifically in their notes. Data were abstracted from treatment notes using a procedure modeled on prior qualitative chart review studies.17,18 The team created narrative case profiles of each participant based on the treatment notes. Using an iterative coding process, a sub-team of four researchers reviewed these case profiles to identify behaviors, resources, or qualities related to pressure injury prevention. Through content analysis19 and data reconciliation meetings, the sub-team identified eight themes that were then refined through discussion with the larger study team. The data analytic process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data analysis process. PUPP = Pressure Ulcer Prevention Program; PUPS = Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study.

Results

Our analysis process resulted in the identification of eight potentially protective factors. We subdivided each of these eight factors into two categories: (1) factors that were present prior to the intervention and (2) factors that developed postintervention and may therefore have been developed or altered by the intervention. The proportion of preexisting factors compared to intervention-related factors varied among the themes. Table 2 provides an overview of the eight themes and examples of both preexisting and intervention-related factors.

Table 2.

Themes

| Theme | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Preexisting factors | Support from intervention | |

| 1. Meaningful activity | Rosa* participated in exercise, volunteer work as president of her nursing home's resident council, oil painting, and providing legal advice to staff and residents (she is a former lawyer). | Michael was connected to Homeboy Industries where he began taking GED courses and showed interest in other services. |

| 2. Motivation to prevent negative health outcomes | Joe was committed to remaining pressure injury-free in order to avoid additional surgeries, which could result in amputation. | Roberta was motivated to increase her preventive practices, saying (about the PUPP intervention) “I should have done something like this a long time ago.” |

3. Stability/resources

|

Environment/housing: David began the study with a number of buffers, including a stable living situation. Caregiver support: Miquela had caregiver assistance for 3 hours/day to help with activities of daily living. Finances: Teresa had adequate finances as a result of a settlement from the accident in which she was injured. |

Environment/housing: Modesto moved into a new apartment with his mother that was more accessible. Finances: Janis filled out paperwork and qualified for Medi-Cal insurance. |

| 4. Equipment | Keyla's equipment was in good condition and she was proactive about having things repaired and identifying new equipment needs. | The PUPS equipment allowance enabled Dolores to obtain a kitchen timer, watch, and MP3 player to assist with timing pressure reliefs and encouraging more bed rest. A grant funded by the SCI Special Fund provided an automated turning mattress. The OT also encouraged her to purchase different clothing to reduce risk of injury development. |

| 5. Communication & self-advocacy skills | Prior to PUPS, Chris successfully received grants for equipment and became part of the California Department of Rehabilitation independently, which provided him with a desktop, school supplies, and modifications for a van. | By the end of the intervention, Vicky felt more comfortable asking questions and making demands of health care professionals. OT helped her advocate to get a new suction machine despite concerns about “irritating” the vendor. |

6. Behaviors/activities

|

Proactive response: Pamela sought counseling to deal with stress over loss of meaningful activities. Health-promoting behaviors (exercise): Magdalena participates in regular aerobic and strength-building exercise. Knowledge and skills: Daniel indicates that he understands how pressure injuries occur. |

Proactive response: Josiah learned to cancel important activities (teaching bible study classes) in order to stay in bed and heal skin. Health-promoting behaviors (skin inspections): Steven began using a digital camera to perform skin checks. Knowledge and skills: Maria developed a new understanding during the intervention that her skin is more fragile than it used to be and has become more vigilant in her pressure relief program. |

| 7. Personal traits |

Attitude: Rob is organized and in strong control of his life; he knows what he needs, makes good decisions, and advocates for himself as needed. Assuming adult roles & responsibilities: Jerry was a lawyer before a tumor resulted in an SCI. Spirituality: Antonio “uses spirituality to help with his depression.” He uses reflections to focus on other things when he is in pain, as well as positive thinking, jazz, and gospel music. |

Attitude: Jerome shared that one of the ways he has changed through the program is that he has learned to become more patient. Assuming adult roles & responsibilities: OT focused on teaching Sam the importance of being happy and controlling his anger as a way to improve health and reduce pressure injury development. |

| 8. Physical factors |

Youthful body: Tyler was injured while in high school and is still very young. Health prior: Doctors credit Nick's “health and fitness” for his survival in a motorcycle accident. |

(n/a prior to treatment by definition) |

Note: OT = occupational therapist; PUPS = Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study.

a All names are pseudonymns.

Theme one: Meaningful activity

Some participants described engaging in personally meaningful activities (eg, church, work, education, and leisure activities) during the PUPP intervention and, in most cases, they had been doing so prior to their study participation. Their participation in these activities provided enduring motivation to remain pressure injury-free. For example, one participant stated that she enjoyed horseback riding and pushed herself to continue doing so during the PUPP intervention. Several participants also discovered new meaningful activities as a result of the PUPP intervention. For example, one participant began volunteering with an organization that he discovered as a result of the PUPP intervention.

Theme two: Motivation to prevent negative health outcomes

In contrast to those participants whose motivation to stay healthy stemmed from a desire to participate in activities, other participants were motivated by a strong desire to avoid negative health outcomes. For instance, three participants reported that they did not want to experience more surgeries to repair skin breakdowns or did not want to “be a patient” again. In all cases except for one, the desire to avoid negative health outcomes preceded enrollment in the study.

Theme three: Stability/resources

A common factor that was nearly always preexisting before receiving the intervention was stability in life circumstances and access to resources. This theme was divided into three subcategories: environment/housing, caregiver support, and finances.

Environment/housing. Stable housing proved to be an important resource for 11 participants in the intervention. Stable housing refers to a safe, consistent place to live either alone or with others who do not increase one's health risks (eg, individuals who do not use illicit drugs, etc). According to participants, the consistency of the environment allowed them to develop effective self-care routines. Three participants obtained better housing as a result of the intervention, including one who learned how his inaccessible apartment was increasing his pressure injury risk and chose to move into an accessible unit where he could easily navigate in his wheelchair.

Caregiver support. Consistent, dependable support from caregivers who were either paid assistants or family members represented a common theme amongst participants who did not develop pressure injuries. Caregivers helped participants to maintain self-care routines, including skin care and pressure injury prevention. For example, one OT note stated, “The lack of [client] skin breakdown was facilitated by skin inspections and wound care from the client's mother and other attendants.” In all 13 cases that were identified with a strong caregiver presence, the caregiver support was in place prior to beginning the intervention.

Finances. Financial stability was an important factor in pressure injury prevention. Adequate finances enabled participants to access other resources, such as housing, equipment, and medical insurance. Sources of financial support varied; two received settlements from lawsuits related to their SCI, two had income from employment, and some received support from others, including church communities. In all but one case, financial support was in place before the intervention. One participant applied for Medi-Cal insurance with support from the OT, thereby gaining access to health resources that were instrumental in pressure injury prevention.

Theme four: Equipment

Participants stated that their access to and maintenance of adequate medical equipment, especially seating surfaces and skin inspection aids, was critical to the prevention of pressure injuries. In some cases, participants who began the intervention with appropriate equipment were able to afford their equipment as a result of preexisting access to financial resources. However, many participants were able to acquire equipment as a result of the PUPP intervention, which allowed each participant a $400 equipment budget. These funds were spent in consultation with the OTs, who assisted with planning and prioritization. In many instances, OTs worked with participants to apply for grant funding or to navigate health insurance bureaucracy to purchase more expensive equipment items. Examples of equipment purchased during PUPS enrollment that may have contributed to pressure injury prevention included new or updated wheelchairs (n = 4), wheelchair cushions (n = 4), shower chairs or roll-in showers (n = 5), transfer boards (n = 1), specialty mattresses (n = 3), alarm clocks/watches to aid in pressure relief timing (n = 2), and non-restrictive or padded clothing (n = 3).

Theme five: Communication and self-advocacy skills

The ability to effectively communicate and advocate for oneself in health care, family, and social settings emerged as a common factor among individuals who did not develop pressure injuries. OT interveners noted abilities to clearly communicate needs and concerns to health care providers (n = 6), confidently provide direction to caregivers (n = 4), and adeptly navigate complex health care bureaucracies (n = 3) among participants who had developed excellent interpersonal skills prior to the intervention. Improving interpersonal skills often became a focus of the PUPP intervention for participants who demonstrated difficulty with communication and self-advocacy skills. In some cases, participants became timid or passive in health care contexts (n= 2), while another displayed forceful or aggressive behaviors in medical settings. In both situations, therapists assisted clients with developing the skills to communicate more effectively in order to meet their needs and potentially prevent pressure injuries.

Theme six: Health-promoting behaviors and activities

Within the broad category of behaviors and activities that may have served as protective factors, three subthemes were identified: proactive response to health care issues, adoption of health-promoting behaviors, and acquisition of health-promoting knowledge and skills.

Proactive response to health care issues. Some participants were observed to proactively address issues such as emergent episodes of heightened risk for pressure injuries and other health problems. OTs noted that these participants notified health care providers at the first sign of skin breakdown, took immediate action when issues arose, and reported feeling satisfaction after effectively taking care of their skin (n = 4). For those participants who did not proactively respond to health problems, therapists worked with participants to heighten their level of vigilance for potential health issues and to address them immediately, before they became more serious. For example, participants who noticed skin redness (which could indicate an emerging pressure injury) were encouraged to be more attentive in skin inspections and pressure reliefs and allow the skin to recover so that it did not progress to a severe pressure injury (n = 2).

Adoption of health-promoting behaviors. Some participants were noted to independently engage in health-promoting behaviors that may have protected against pressure injuries (n = 2), while others adopted health-promoting behaviors as a result of the intervention (n = 5). These behaviors included following a healthy diet, being physically active, regularly performing skin inspections and pressure redistribution, limiting sitting time, and using positive coping strategies to manage pain or emotional distress. For example, one OT wrote of a participant, “Client lost a significant amount of weight secondary to decreased consumption of soda.”

Acquisition of health-promoting knowledge and skills. OTs described that 14 participants acquired and applied knowledge and skills about pressure injury prevention behaviors through the PUPP intervention. For example, participants learned how to more effectively perform transfers, use a wheelchair, and inspect their skin, which increased the likelihood of these activities being carried out successfully (n = 4). An OT described one participant by saying, “During the intervention, the client progressed from being unwilling to consider doing pressure reliefs (she dislikes how they change her positioning in the wheelchair) to doing 1–2 a day.” Both pressure injury-specific health-promoting behaviors and more general health-promoting behaviors may have safeguarded against the development of pressure injuries.

Theme seven: Personal traits

Certain personal traits appear to have protected against pressure injuries in the PUPS population. Primarily, participants who were described as demonstrating a positive attitude by their therapists were also more likely to be highly motivated to prevent skin breakdowns. These participants also reported feeling more in control of their lives and demonstrated more consistency in performing pressure injury prevention techniques (n = 3). For example, one therapist described her participant by saying, “He sees life on the bright side, preferring to enumerate the good things in his life, and does not choose to dwell on the negatives.” For this participant, a positive attitude seems to have resulted in greater openness to enacting new behavioral strategies such as eating fewer tortillas with each meal to reduce overall carbohydrate intake.

In some cases, the PUPP intervention helped participants to develop a more positive attitude. For instance, extreme vigilance about pressure injury prevention had caused one participant significant stress. The therapist stated that she believed the intervention had helped this client develop a healthy balance of alertness around pressure injury prevention without feelings of panic and doom. Spirituality also appears to have protected against pressure injuries for some PUPS participants. For participants who reported being spiritual prior to the intervention, spirituality provided purpose and helped ameliorate depression, pain, and pessimism about their health condition (n = 3). Some participants who were spiritual also found encouragement and social support from their church communities, which helped boost their sense of self-efficacy surrounding pressure injury prevention (n = 4).

Theme eight: Physical factors

Participants' prior physical condition may have served as a protective factor against the development of pressure injuries. Specifically, individuals who recently acquired an SCI and those who acquired an SCI at a younger age tended to develop less serious pressure injuries over the course of the PUPP intervention period (n = 2). This trend could be due to these participants' resilient bodies and the resulting ability to prevent and heal minor pressure injuries. Another potentially protective factor in this category included being physically fit and in general good health prior to the intervention (n = 2). For example, one doctor credited one participant's significant “health and fitness” for his survival in a motorcycle accident. After the motorcycle accident, this participant remained pressure injury-free, in part because he maintained physical and mental health using regular exercise.

Discussion

The results of the parent RCT, PUPS, showed no significant differences in pressure injury incidence between intervention and control groups among community-dwelling, medically underserved adults with SCI.15 Because the intervention was not associated with pressure injury incidence as measured in the study, we wanted to investigate whether there were factors other than those that were quantitatively measured that may protect against skin breakdown. Findings from a qualitative analysis of treatment notes for pressure injury-free patients in the intervention arm reflect pressure injury prevention factors that exist on a continuum from modifiable to non-modifiable. For example, health-promoting behaviors and engagement in meaningful activities often appeared to occur as a result of the PUPP intervention and could likely be addressed in other intervention approaches. Self-determination theory suggests that self-motivation and other aspects of self-regulation can be influenced by manipulating environmental factors.20 On the other hand, protective factors such as personal traits and physical factors appear to be less malleable. Factors such as financial and housing stability are modifiable, though typically not through health interventions.

Consistent with prior research,13,14 general health-promoting habits such as avoiding overweight or underweight, eating a healthy diet, and engaging in moderate exercise appeared to protect against pressure injury incidence. The methods in our analysis were substantively different from prior work that used cross-sectional quantitative data to identify protective factors. Similar results using different study designs add to the strength of the findings. On the other hand, no interventions tested that are reported in the literature have been demonstrated to reduce pressure injury incidence in adults with SCI.11 These protective factors may need to be featured more centrally in future intervention design.

Health care providers and researchers should be aware that many of the protective factors identified in this study may be “double-edged swords” in that they also have the potential to play a part in pressure injury development. For example, engagement in meaningful activities appears to be a protective factor; however, becoming immersed in a meaningful activity and thereby forgetting pressure injury prevention behaviors like pressure redistribution could increase the likelihood of skin breakdown. For this reason, no single factor can be purely protective in every instance, and the nuances of each individual's context and history must be taken into consideration when designing therapeutic interventions to prevent pressure injuries for this population.21

The sample in the parent RCT consisted almost entirely of individuals who were ethnic minorities, many of whom reported monthly incomes below the federal poverty line. Yet, many were able to avoid pressure injuries. Ensuring all individuals with SCI have access to many of the protective factors identified in our analysis would require larger-scale policy changes. For example, equal access to financial resources, equipment, caregivers, and adequate housing would necessitate alterations in local and national health care and housing policies, especially for participants of lower socioeconomic status. Further research into the efficacy of each of these protective factors in pressure injury prevention in socioeconomically diverse populations is needed to help justify allocation of resources to address policy and health care approaches that protect against pressure injuries and, ultimately, reduce lifetime medical costs for individuals with SCI.

Limitations and directions for future research

The participants in the PUPS study were primarily non-White and of low socioeconomic status; therefore, the results of the current analysis apply to this unique population and are not necessarily generalizable. Additional research is necessary to identify the protective factors that remain consistent across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups. Although our findings are consistent with prior studies, the results should be interpreted with caution due to some limitations to the study design. The treatment notes used as data in this analysis were designed to document and track participants' progress and record how each OT tailored the intervention for each participant. They were not originally intended to be used to investigate protective factors. As such, the level of detail and comprehensiveness varied among treatment notes. Narrative case profiles were not checked by the original OT interveners, so progress notes may have been misinterpreted by the research team. Had the team anticipated such rich information about possible pressure injury prevention strategies and protective factors in the individual narratives, we could have created a template to ensure that all possible risk and protective factors were identified during the intervention period.

In addition, unconscious bias may have been introduced during the interpretation of treatment notes by the intervention team, as the unique perspectives of each team member may have colored the generation of case profiles. Finally, we were unable to complete a similar analysis using participants in the control arm of the parent study because they did not receive a study-specific intervention; therefore, there were no treatment notes. This circumstance makes it challenging to confirm whether or not some factors were actually modified by the PUPP intervention. A separate, ongoing analysis has been completed to determine whether the factors detailed in this article were also present in individuals who developed medically serious pressure injuries during the course of the intervention.22

Despite its limitations, this analysis represents a unique contribution to research and practice by delineating protective factors that are nonmodifiable versus modifiable. Considering factors that are potentially modifiable by intervention and/or policy may allow for more appropriate and targeted provision of services, resources, and policy initiatives. In addition, this study offers an analysis of an underrepresented group of racial/ethnic minorities with lower socioeconomic status. Future research should pursue a targeted and deeper assessment of protective factors and preventive strategies in these populations, particularly in relation to intervenable areas such as lifestyle and environment.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to inform new intervention approaches by analyzing treatment notes from individuals who did not develop medically serious pressure injuries during a pressure injury prevention intervention program. We identified eight types of protective factors: meaningful activity, motivation to prevent negative health outcomes, stability/resources, equipment, communication and self-advocacy skills, personal traits, physical factors, and behaviors/activities. Health care practitioners working with this population may be able to help prevent the development of pressure injuries by focusing on helping patients acquire medical equipment and facilitating the development of sustainable, health-promoting habits and routines. However, our findings also suggest that substantive policy changes may be necessary to facilitate access to adequate resources, particularly housing and equipment, for individuals with SCI. Further research is needed to understand the complex interplay of risk and protective factors for pressure injuries in adults with SCI, particularly with individuals from minority groups and those with low socioeconomic status.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01HD056267 from the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (NCMRR) within the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, to the University of Southern California.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guilcher SJ, Craven BC, Lemieux-Charles L, Casciaro T, McColl MA, Jaglal SB. Secondary health conditions and spinal cord injury: An uphill battle in the journey of care. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(11):894–906. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.721048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel NPUAP pressure injury stages. http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/npuap-pressure-injury-stages/ Accessed November 2016.

- 3.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:S40. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2001.11753592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brem H, Maggi J, Nierman D et al. High cost of stage IV pressure ulcers. Am J Surg. 2010;200(4):473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan BC, Nanwa N, Mittmann N, Bryant D, Coyte PC, Houghton PE. The average cost of pressure ulcer management in a community dwelling spinal cord injury population. Int Wound J. 2013;10(4):431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeVivo MJ, Chen Y. Trends in new injuries, prevalent cases, and aging with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(3):332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark FA, Jackson JM, Scott MD et al. Data-based models of how pressure ulcers develop in daily-living contexts of adults with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(11):1516–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson J, Carlson M, Rubayi S et al. Qualitative study of principles pertaining to lifestyle and pressure ulcer risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):567–578. doi: 10.3109/09638280903183829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozelie R, Sipple C, Foy T et al. SCIRehab Project series: The occupational therapy taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):283–297. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman S, Gorecki C, Nelson EA et al. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development: Systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(7):974–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cogan AM, Blanchard J, Garber SL, Vigen CL, Carlson M, Clark FA. Systematic review of behavioral and educational interventions to prevent pressure ulcers in adults with spinal cord injury. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(7):871–880. doi: 10.1177/0269215516660855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regan MA, Teasell RW, Wolfe DL, Keast D, Mortenson WB, Aubut JA. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(2):213–231. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.08.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause J, Broderick L. Patterns of recurrent pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: Identification of risk and protective factors 5 or more years after onset. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause J, Vines C, Farley T, Sniezak J, Coker J. An exploratory study of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: Relationship to protective behaviors and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:13–113. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.18050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark F, Pyatak EA, Carlson M et al. Implementing trials of complex interventions in community settings: The USC–Rancho Los Amigos Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study (PUPS) Clinical Trials. 2014;11(2):218–229. doi: 10.1177/1740774514521904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson M, Vigen CL, Rubayi S et al. Lifestyle intervention for adults with spinal cord injury: Results of the USC–RLANRC Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;18:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2017.1313931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gearing R, Mian I, Barber J, Ickowicz A. A methodology for conducting retrospective chart review research in child and adolescent psychiatry. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:126–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockwood K, Fay S, Hamilton L, Ross E, Moorhouse P. Good days and bad days in dementia: A qualitative chart review of variable symptom expression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1236–1246. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000222. doi:10.1017/S1041610214000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson J, Carlson M, Rubayi S et al. Qualitative study of principles pertaining to lifestyle and pressure ulcer risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):567–578. doi: 10.3109/09638280903183829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Floríndez LI, Carlson M, Pyatak EA A qualitative analysis of pressure injury development among medically underserved adults with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]