Abstract

Significance:

Young adults with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other severe mental illnesses (SMI) have high rates of smoking, but little research has evaluated predictors of cessation activity and treatment utilization in this group.

Methods:

We assessed attitudes, beliefs, social norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, quit attempts, treatment utilization, and cessation among 58 smokers with SMI, age 18-30, enrolled in a randomized pilot study comparing a brief interactive/motivational vs. a static/educational computerized intervention. Subjects were assessed at baseline, post intervention, and 3-month follow-up.

Results:

Over follow-up, one-third of participants self-reported quit attempts. Baseline measures indicating lower breath CO, greater intention to quit, higher perceptions of stigma, psychological benefits of smoking, and symptom distress were associated with quit attempts, whereas gender, diagnosis, social support, attitudes about smoking, and use of cessation treatment were not. In the multivariate analysis, lower breath CO, higher intention to quit and symptom distress were significantly related to quit attempts.

Only 5% of participants utilized verified cessation treatment during followup. Consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior, attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control regarding cessation treatments correlated significantly with intention to use treatment. Norms and beliefs about treatment were somewhat positive and some improved after intervention, with a pattern significantly favoring the interactive intervention, but intentions to use treatments remained low, consistent with low treatment utilization.

Conclusions:

Perceptions of traditional cessation treatments improved somewhat after brief interventions, but most young adult smokers with SMI did not use cessation treatment. Instead, interventions led to quit attempts without treatment.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Technology-delivered intervention, Young adult, Serious mental illness

1. Introduction

Although public health efforts have resulted in a dramatic reduction in the number of young people who initiate smoking, young adults with mental health symptoms or distress are more likely to smoke than those without mental health issues (Griesler, Hu, Schaffran, & Kandel, 2008; Hu, Davies, & Kandel, 2006; Jamal et al., 2016). Rates of smoking are even higher (50-80%) among young adults whose mental illness is severe, chronic or disabling, including those with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (serious mental illness; SMI (Barnes et al., 2006; Correll et al., 2014; Vanable, Carey, Carey, & Maisto, 2003; Wade et al., 2006)). Because the negative health effects of toxins in tobacco smoke build over time (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014), helping young smokers quit prior to many years of exposure can prevent disease and early mortality (Doll, Peto, Boreham, & Sutherland, 2004; Taghizadeh, Vonk, & Boezen, 2016).

Although many young adults wish to quit (Pirie, Murray, & Luepker, 1991; Tucker, Ellickson, Orlando, & Klein, 2005) and are more likely than older adults to make quit attempts (CDC, 2011), they are less likely to report using cessation treatment counseling or medications that have the potential to increase the likelihood of success in their quit attempt (2011; DeBernardo et al., 1999; Hines; Kahende et al., 2017; Solberg, Boyle, McCarty, Asche, & Thoele, 2007). Further, some studies indicate that young adults are the age group least likely to achieve abstinence (Agrawal, Sartor, Pergadia, Huizink, & Lynskey, 2008; Chen & Kandel, 1995). Young adults with SMI show similar patterns of quit attempts (Brunette et al., 2017; Catchpole, McLeod, Brownlie, Allison, & Grewal, 2017; Morris et al., 2011) and lack of interest in traditional evidence-based cessation treatment (Brunette et al., 2017; Catchpole et al., 2017; Grana, Ramo, Fromont, Hall, & Prochaska, 2012; Leatherdale & McDonald, 2007) compared to young adults without SMI, but further information is needed about quit attempts as one step in the process towards reaching permanent abstinence.

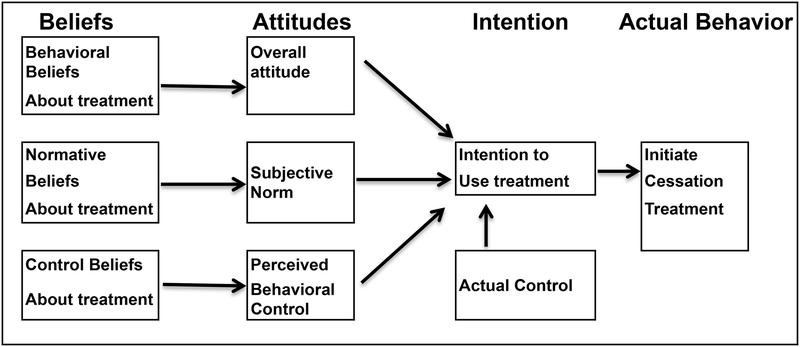

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) can be used to understand health behavior and to design effective interventions to improve it (Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, 2010). Under this theory, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control over the behavior (e.g. using smoking cessation treatment) lead to intention or motivation to enact the behavior (Figure 1)(I. Ajzen, 1991). These constructs have predicted intention to quit smoking (Godin & Gerjo, 1996; Norman, Conner, & Bell, 1999) and to change other health behaviors in the general population. The subjective beliefs that underlie attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control may be unique within different populations.

Figure 1.

Theory of Planned Behavior.

In relation to social norms, research in the general population has shown that social stigma, or the perception of being discriminated against, influences smoking and quitting behavior (Hammett et al., 2017; O’Connor, Rees, Rivard, Hatsukami, & Cummings, 2017; Stuber, Galea, & Link, 2008). Among smokers with mental illness, greater levels of self-stigma regarding smoking were associated with greater readiness to quit (Brown-Johnson et al., 2015), but we are not aware of research that has evaluated perceptions of smoking-related stigma among young adult smokers with SMI.

Additionally, although many studies have described middle-aged smokers with SMI (e.g. (Aschbrenner et al., 2017; Lucksted, McGuire, Postrado, Kreyenbuhl, & Dixon, 2004; Wehring et al., 2012)), few studies have described the beliefs, attitudes, social context and perceptions of social norms related to smoking among young adults with mental illness (Grana et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2011), and research on beliefs about smoking cessation and use of cessation treatment among young smokers with SMI is also sparse (Catchpole et al., 2017; Leatherdale & McDonald, 2007; Morris et al., 2011). A fuller understanding of the characteristics, beliefs, attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control about cessation treatment, to is needed to inform health communications and intervention development for groups that have not yet responded robustly to tobacco control efforts, such as young adults with SMI.

This study includes secondary analyses of data obtained in a randomized pilot study comparing two brief, web-based interventions for smoking cessation among young adult smokers with SMI. In order to better understand pathways to quitting, we explored data predicting two intermediate outcomes, self-reported quit attempts and intention to use cessation treatment. First, we explored associations between smoker characteristics and their quit attempts after intervention over the 3-month follow-up. Second, guided by the Theory of Planned Behavior, we explored whether smoker beliefs about cessation treatment, attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control over using cessation treatment changed after intervention and whether they were related to intention to use cessation treatment. We assessed these relationships for each of three treatment types: nicotine replacement therapy, cessation medications, and cessation counseling.

2. Methods

2.1. Enrollment and Study Participants

The parent study methods and primary outcomes are described elsewhere (Brunette et al., 2017). Potential participants were recruited from four treatment programs serving young adults with SMI. We enrolled English-speaking, daily smokers with SMI, age 18-30 years, who were psychiatrically stable in outpatient treatment for mental illness and who were willing and able to give informed consent. For this analysis, we included participants who were assigned to a treatment intervention – 65 participants were consented and assessed for eligibility; 58 were eligible, randomized and received an intervention, and, overall, 50 (86.2%) were assessed at the three-month follow-up (23 (82.1%) in the NCI Education group, and 27/30 (90%) in the Let’s Talk About Smoking group).

2.2. Study procedures

After baseline assessment, participants were randomized to receive one of two brief interventions within 2 weeks. After either intervention, participants completed questions regarding cessation treatment beliefs and attitudes (exploratory outcomes). Research staff then provided participants referral information to available cessation treatment (cessation medications and counseling, Quitline). All participants completed the intervention to which they were assigned in a single office visit. Three months later, research interviewers assessed participants for use of cessation treatment (main outcome), smoking characteristics, quit attempts and biologically verified abstinence (secondary outcome). All participants were paid $50 for each research assessment visit.

2.2.1. Interventions

2.2.1.2. Electronic decision support system for smoking cessation

This interactive/motivational web-based computer program, Let’s Talk About Smoking, is tailored for smokers with SMI and designed to increase motivation to quit smoking using evidence based treatment Its initial development and content have been described previously (Ferron etal., 2011). It is a linear, modularized, interactive program that takes 30-60 minutes to complete. A young adult video program host, who identifies herself as an ex-smoker with mental illness, guides users through modules, each with assessments and exercises used in motivational interviewing and health decision aid systems. For this study, we further tailored the content to enhance its relevance for young adults. This version provided less emphasis on health and more emphasis on the financial and social impacts of smoking and quitting.

2.2.1.2. Computerized National Cancer Institute Patient Education

A reproduced version of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) patient educational handout (“Cigarette Smoking: Health Risks and How to Quit (PDQ®)–Patient Version,”) provided static information about smoking-related diseases and smoking cessation treatments. The content was provided to participants via laptop computer in a format similar to the decision support system: large black font on a white background with no distracting images; one concept per page in bulleted sentences; and automated audio that read the content to users if they wished. By providing the handout in a similarly-produced, computerized format with audio, this control condition was designed to provide a contrast for the tailored, interactive and motivational content of the electronic decision support system.

2.3. Measures

Demographics and smoking history were assessed with a structured interview. Physician-completed DSM-IV-TR psychiatric diagnoses and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) were obtained from clinic chart review. Psychiatric symptom distress was assessed at baseline with the 14-item modified Colorado Symptom Index (Conrad et al., 2001; Shern et al., 1994). General social support was assessed with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, a 12-item scale that measures perceived support from family, friends and significant others.

2.3.1. Smoking characteristics

We assessed participants for level of nicotine dependence with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine dependence, a 5-item measure, at baseline and three months (Fagerström, 1978; Weinberger et al., 2007). Attitudes about smoking were assessed with the Attitudes Towards Smoking Scale, an 18-item instrument with three subscales (adverse effects, psychoactive benefits, pleasure) (Etter, Humair, Bergman, & Perneger, 2000). A smoking stigma scale (Stuber, Galea, Link, & Xa, 2009) was used that includes 11 questions assessing attitudes and beliefs regarding social discrimination related to smoking, such as “Because of smoking, I have had difficulty renting an apartment” with True and False or 4-point Likert scale answer options (strongly disagree to strongly agree).

For attitudes about cessation treatment, participants were assessed at baseline and after the intervention according to the five components of the Theory of Planned Behavior (i.e. beliefs, attitudes, subjective social norms, perceived behavioral control for the cessation treatment, intention to quit and to use cessation treatment) using a questionnaire the authors developed using Ajzen’s method (Ajzen, 2006). Since the scale is under development, single items were used to represent constructs from the theory for each type of smoking cessation treatment.

2.3.2. Use of smoking cessation treatment and social support for quitting

The smoking cessation treatment checklist was used to obtain all self-reported use of cessation treatment (including nicotine replacement therapy) and use of other supports to quit (e.g. friends, family, clergy). Use of cessation treatment (defined as at least one day of use) was verified via clinic record review, phone calls to clinicians, and viewing bottles of medications and nicotine replacement at the three-month assessment.

2.3.3. Quit Attempts and Abstinence

Biologically verified abstinence was assessed at three months, when self-reported one-week abstinence was verified with expired carbon monoxide (CO) (Smokelyzer Breath Carbon Monoxide Monitor, Bedfont Scientific) (Benowitz et al., 2002; Jarvis, Russell, & Saloojee, 1980). A quit attempt was defined as an attempt to quit with at least 24 hours of abstinence. Self-reported quit attempts with at least one day of abstinence were captured with the Timeline Follow-back method at three months (Brown et al., 1998; Sobell & Sobell, 1992; Sobell & Sobell, 1996). With this well-validated method, trained research staff assessed amount and frequency of smoking and abstinence week-by-week using a calendar to cue memories of smoking and abstinence (Drake, Mueser, & McHugo, 1996).

2.4. Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to depict the study groups and Chi-Square, Fisher’s Exact or t-tests to assess baseline differences between the two intervention groups and to assess intervention group differences on the main outcome, verified abstinence at three months, with missing conservatively set as smoking.

The first set of analyses included models using logistic regression to evaluate which smoker characteristics and attitudes predicted quit attempts. The next set of analyses addressed Theory of Planned Behavior treatment constructs in relation to intention to use cessation treatment. We conducted exploratory analyses to characterize the average beliefs, attitudes, perceived behavioral control and intentions to use each cessation treatments (i.e. nicotine replacement therapy, cessation medication, counseling) of our sample. We then conducted t-tests for average post-intervention between group differences, and paired t-tests to assess changes in total average group scores after the interventions. Finally, we looked at the relationships between the Theory of Planned Behavior constructs using correlations. In these exploratory analyses, missing observations were left as missing.

3. Results

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 58 young adults (mean age 24.2 years SD=3.6) are reported in Table 1. The mean Fagerstrom nicotine dependence score for the sample was moderate/low, at 4.3 (SD=2). Over a third of the group (37.9%) was thinking about quitting right now or within the next month. Over half of the group lived with family. The vast majority of the group reported receiving generic social support from family and also from friends. The majority of the group also reported having family members who had ever smoked. The group spent time with 4.11±6.3 smokers and 3.45±3.9 non-smokers in the past week. Most participants reported that smoking was not allowed inside where they lived. Over half the group endorsed that they kept their smoking a secret from friends, family, employers or their doctor. Endorsement of experiences of devaluation, social withdrawal and differential treatment due to smoking were moderately low.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics of 58 study participants

| Motivational Decision Support (LTAS) N=30 | Computerized NCI Education (NCI) N=28 | |

|---|---|---|

|

Demographics | ||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 23.53 (3.9) | 24.96 (3.2) |

| Gender, N men (%) | 20 (66.7%) | 19 (67.9%) |

| Years education, Mean (SD) | 11.70 (1.4) | 11.57 (2.0) |

| Race | ||

| White, N (%) | 17 (56.7%) | 16 (57.1%) |

| Black, N (%) | 10 (33.3%) | 10 (35.7%) |

| Other, N (%) | 4 (13.3%) | 2 (7.14%) |

| Ethnicity, N Hispanic, (%)* | 6 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Lives with Family, N (%) | 16 (53.3%) | 17 (60.7%) |

| Unmarried, N (%) | 27 (90%) | 26 (92.9%) |

|

Clinical characteristics | ||

| Schizophrenia/affective diagnosis, N (%) | 12 (40%) | 14 (50%) |

| Mood/anxiety diagnoses, N (%) | 18 (60%) | 14 (50%) |

| Colorado Symptom Index Score, Mean (SD) | 17.2 (11.5) | 19.0 (9.3) |

| Global Assessment of Functioning, Mean (SD) | 44.7 (6.6) | 47.3 (5.7) |

| Lifetime hospitalizations, Mean (SD) | 4.6 (4.9) | 7.4 (10.3) |

|

Smoking characteristics and Attitudes | ||

| Cigarettes/day, Mean (SD) | 10.9 (8.6) | 13.9 (9.4) |

| Fagerstrom dependence score, Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.9) | 4.3 (2.1) |

| Smokes menthol, N (%) | 20 (69%) | 17 (60.7%) |

| Used e-cigarettes past 3 months, N (%) | 11 (36.7%) | 8 (28.6%) |

| Attitudes Towards Smoking | ||

| Benefits Subscale, Mean (SD) | 13.6 (3.5) | 12.75 (3.8) |

| Pleasure Subscale, Mean (SD) | 14.5 (2.9) | 15.21 (3.2) |

| Adverse Subscale, Mean (SD) | 40.33 (6.7) | 37.54 (8.2) |

| Total Attitudes Towards Smoking Scale, Mean (SD) | −12.23 (8.6) | −9.57 (9.4) |

| Thinking of quitting in next month, N (%) | 10 (33.3%) | 12 (42.9%) |

|

Social Context | ||

| Parent ever smoked, N (%) | 22 (78.6%) | 20 (68.7%) |

| Sibling ever smoked, N (%) | 15 (55.6%) | 19 (63.3%) |

| Smoking allowed inside at residence, N (%) | 9 (32.1%) | 6 (20.7%) |

| Mean # people smoked with past week, (SD) | 3.07 (6.47) | 5.22 (6.02) |

| Mean # non-smokers spent time with past week, (SD) | 3.64 (3.41) | 3.26 (4.41) |

|

Social Support Scale | ||

| Social Support from Friends, N (%) | 23 (76.7%) | 20 (71.4%) |

| Social Support Scale Score - among those endorsing friends1, mean (SD) | 19.26 (5.9) | 19 (6) |

| Social Support from Family, N (%) | 27 (90%) | 25 (89.29%) |

| Social Support Scale Score among those endorsing family,1 mean (SD) | 20.0 (6.0) | 20.6 (5.4) |

| Social Support from Special Person, N (%) | 21 (70%) | 16 (57%) |

| Social Support Scale Score-among those endorsing Special Person,1 mean (SD) | 22.86 (4.8) | 22.25 (6.5) |

|

Smoking Stigma Scale | ||

| Devaluation Subscale Score (Range 1-8), Mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.2) |

| Social Withdrawal Subscale Score (Range 1-12), Mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.6) |

| Endorses Secrecy, N (%) | 16 (60.7) | 17 (53.3) |

| Endorses Differential Treatment, N (%) | 6 (21.4) | 6 (20.0) |

NCI=National Cancer Institute, LTAS=Let’s Talk About Smoking Website, N = number, SD=Standard Deviation

P<.05; (X2=6.42, p=.01)

Social support subscale range 4-28

3.1. Abstinence and use of cessation treatment

As previously reported (Brunette et al., 2017), at three-month followup, over one third of the group reported that they had tried to quit and achieved at least one day of self-reported abstinence (not different between intervention groups). Four of the 50 participants assessed at follow-up had verified abstinence at that assessment (significantly greater in the interactive/motivation intervention group than in the static/education group (4 [14.8%] vs. 0, Chi2= 4.0, p<.05).

Although we previously hypothesized that cessation treatment would be an important avenue to quit attempts and abstinence, only 5% of participants used verifiable nicotine replacement therapy, and none used any other verifiable treatment. Additional participants used cessation treatment that was not verified. Almost 14% of participants self-reported use of nicotine replacement therapy, 6.9% self-reported talking with a counselor about quitting, and 5.2% self-reported talking to a doctor about quitting. Additionally, 19% self-reported that talking with a friend helped with quitting (not different between intervention groups).

3.2. Predictors of quit attempts and abstinence

Logistic regression assessed whether smoker characteristics predicted self-reported quit attempts with at least one day of abstinence. Predictors of self-reported quit attempts included: lower breath CO (OR=0.92, 95% CI=.85-.99; p=.03), greater intention to quit (OR=5.25, 95% CI=1.66-16.59; p=.005), higher symptom distress (CSI, OR=1.07, 95% CI = 1.0-1.1, p=.02), greater perceptions of the benefits of smoking (OR=1.28 , 95% CI=1.03-1.59, p=.03), and greater perceptions of smoking stigma (social withdrawal scale scores OR= 1.49, 95% CI=1.02-2.16, p=.04). Gender, diagnosis, use of verified cessation treatment, social support for quitting, and generic social support were not associated with self-reported quit attempts. In a multivariate analysis including significant variables, baseline lower breath CO, intention to quit, and higher symptom distress remained significant predictors of quit attempts.

The overall small proportion of abstinent participants precluded valid analyses predicting confirmed abstinence. Of participants who were abstinent at follow-up, none used verifiable cessation treatment. Abstinent participants also self-reported cessation supports that were not verifiable. One participant self-reported talking with a counselor, and two self-reported that talking to a friend about quitting assisted with cessation.

3.3. Theory of Planned Behavior predictors of intention to use cessation treatment: Beliefs, attitudes, social norms, perceived behavioral control over cessation treatment

Mean perceived social norm beliefs (indirect norms) and direct social norms for cessation treatment are shown in Table 2. Mean beliefs about family and friend approval for quitting cold turkey and also for using cessation treatment were somewhat positive (between 4 and 6 on a scale of 1 to 7). Three of the six social norm beliefs significantly improved after intervention, but were not different between intervention groups. Most people did not know someone who had used cessation treatments (direct social norms).

Table 2.

Social norms for cessation treatment before and after intervention among young adult smokers with SMI

| Indirect Social Norm Beliefs | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post Intervention Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Quitting without medication assistance | Range 1-7 | Range 1-7 |

| People in my family would approve of me quitting cold turkey. | 5.22(1.85) | 5.41(1.91) |

| My friends and boyfriend/girlfriend would approve of me quitting cold turkey. | 4.81(1.91) | 4.78(1.89) |

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy | ||

| People in my family would approve of me using nicotine replacement therapy | 5.62(1.35) | 5.86(1.33) |

| My friends and boyfriend/girlfriend would approve of me using nicotine replacement therapy to quit smoking. | 5.28(1.51) | 5.62(1.42) |

| Cessation Medications | ||

| People in my family would approve of me taking quit smoking medications.*1 | 5.36(1.52) | 5.71(1.40) |

| My friends and boyfriend/girlfriend would approve of me taking quit smoking medications. | 4.93(1.72) | 5.09(1.77) |

| Cessation Counseling | ||

| People who are close to me believe that going to quit smoking counseling would help me.*2 | 4.67(1.67) | 5.34(1.53) |

| Most people who are important to me would go to quit smoking counseling if they tried to quit.*3 | 4.10(1.66) | 4.71(1.71) |

| Direct Social Norm | Baseline N (%) | - |

| I know someone who used nicotine replacement therapy, N (%) | 25 (43.1) | - |

| I know someone who took a quit smoking medication, N (%) | 27 (46.6) | - |

| I know people who have used quit smoking counseling, N (%) | 10 (17.2) | - |

Attitudes scores: 1=Strongly disagree, 7=Strongly agree

Pre-post paired t-test for combined group significantly different, p<.05

t=2.05; p=.04;

t=3.21, p=.002;

t=2.74, p=.008

Beliefs, attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and intention to use cessation treatment are shown in Table 3. Mean belief scores about the efficacy of medication cessation treatments were slightly positive (between 4 and 5 on a scale of 1 to 7). On average, this group did not endorse that they would feel embarrassed by using cessation treatment, nor did they endorse other potential barrier beliefs. There was a pattern of mean efficacy belief scores improving or being more positive in the interactive/motivational intervention group compared to the static/educational intervention group post-intervention.

Table 3.

Beliefs, attitudes, and intention to use cessation treatment among young adult smokers with SMI

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Post Intervention Mean (SD) | Mean Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic smoking cessation attitude2 | |||

| Quitting smoking is… | 5.43(1.37) | 5.71(1.20) | 0.28 |

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy | |||

| Beliefs1 | |||

| Taking nicotine replacement therapy quit medication will help me cut down and quit smoking. | 4.86(1.41) | 5.22(1.43) | 0.36 |

| Taking nicotine replacement therapy quit medication will help reduce my urges to smoke.a1 | 4.93(1.36) | 5.19(1.29) | 0.26 |

| Taking nicotine replacement therapy quit medication will help me deal with my moods while quitting.a2 | 4.36(1.62) | 4.5 (1.49) | 0.14 |

| Nicotine replacement therapy may interact with my mental health medications. | 3.71(1.49) | 3.88(1.58) | 0.17 |

| Taking nicotine replacement therapy would be embarrassing.b1 | 2.24(1.54) | 1.83(1.08) | −0.41 |

| Attitude2 | |||

| Overall, I think NRT is… | 5.55(1.20) | 5.57(1.08) | 0.02 |

| Quit Smoking Medications | |||

| Beliefs1 | |||

| Taking a quit medication will help me cut down and quit smoking.a3 | 4.81(1.48) | 5.05(1.56) | 0.24 |

| Taking a quit medication will help reduce my urges to smoke.b2 | 4.67(1.73) | 5.21(1.48) | 0.53 |

| Taking a quit medication will help me deal with my moods while quitting.a4b3 | 4.38(1.76) | 5.05(1.16) | 0.67 |

| I don’t want to take quit medication because it may interact with my mental health medications. | 4.02(1.49) | 4.23(1.75) | 0.21 |

| Taking a quit medication would be embarrassing. | 2.21(1.17) | 2.26(1.42) | 0.05 |

| Attitude2 | |||

| Overall, I think taking medications to help me cut down and quit smoking is… | 4.84(1.55) | 5.11(1.42) | 0.30 |

| Cessation Counseling | |||

| Beliefs1 | |||

| Going to quit smoking counseling will help me get support to cut down and quit. | # | 5.03(1.89) | |

| Going to quit smoking counseling will be a good place to learn ways to cope with stress without smoking. | # | 5.66(1.31) | |

| I don’t have enough time to attend quit smoking counseling each week for 2 months. | 4.09(1.56) | 3.90(1.75) | −0.19 |

| There’s too much stress in my life to attend quit smoking counseling. | 3.52(1.76) | 3.78(1.79) | 0.26 |

| Attitude2 | |||

| Overall, going to quit smoking counseling is… | # | 3.26(1.76) | |

| Cold turkey attitude1 | |||

| I would prefer to quit smoking without medications (cold turkey). | 4.34(2.12) | 4.16(2.27) | −0.19 |

| Perceived behavioral control1 | |||

| If I wanted, I could use nicotine replacement therapy to quit smoking. | 5.59(1.23) | 5.69(1.44) | 0.10 |

| If I wanted to quit, I would take a quit smoking medication. | 4.57(1.84) | 4.76(1.85) | 0.19 |

| Going to counseling to help me quit smoking each week for 2 months is under my control.b4 | 5.03(1.57) | 5.59(1.69) | 0.55 |

| Intention to use cessation treatment1 | |||

| I have decided to use nicotine replacement therapy to help me quit smoking. | 3.69(1.65) | 3.65(1.94) | −0.02 |

| I have decided to take a medication to help me quit smoking. | # | 3.64(1.89) | |

| I have decided to attend counseling each week for 2 months to help me quit smoking | 3.17(1.58) | 3.40(1.92) | 0.22 |

1=totally disagree, 7=totally agree

1=extremely bad, 7 = extremely good # Question omitted from baseline interview in error

Differences between intervention groups post intervention significant p<.05

t=−2.40, p=.02;

t=−2.16, p=.05;

t=−1.96, p=.03;

t=−2.47, p=.02

Pre-post paired t-test for combined group significantly different, p<.05

t=−2.12, p=.04;

t=2.59, p=.01;

t=3.24, p=.002;

t=2.51, p=.02

In contrast to beliefs, attitudes about quitting with cessation medication treatment were positive, whereas attitudes about cessation counseling were negative, and treatment attitudes did not increase after intervention (Table 3). Mean overall attitudes about quitting cold turkey were neutral and did not change after intervention.

Mean perceived behavioral control (over using cessation treatment) scores were slightly positive on average (about 5 on a scale of 1 to 7) and improved after intervention for perceived control over attending cessation counseling (not different by intervention group; Table 3).

Despite somewhat improved beliefs and positive attitudes about cessation treatments, mean intention to use cessation treatment scores remained somewhat low after the interventions (between 3 and 4 on a scale of 1 to 7; Table 3), corresponding with low actual use of cessation treatment described above. As predicted by the Theory of Planned Behavior, overall treatment attitude scores for NRT, cessation medications, and counseling correlated significantly with intention scores (r=0.30, p=.02;r=0.32, p=.02; & r=0.32, p=.02, respectively); perceived social norms for cessation medications and counseling had trend correlations with intentions (r=0.25, p=.06 & r=0.22, p=.09; respectively); and perceived behavioral control for NRT, counseling and medications correlated significantly with intensions (r=0.46, p=.0004; r=0.63, p=.0001; & r=0.51, p=.000; respectively). Low numbers of participants reporting actual use of cessation treatment precluded valid predictive analyses for use of cessation treatment.

4. Discussion

The descriptive and exploratory analyses from this pilot study provide an in-depth picture of the social context, beliefs, attitudes and intentions of these young adult smokers with SMI, as well as their smoking and cessation behavior after brief interventions. These data suggest that the social context of many young adult smokers with SMI includes potential supports for cessation in terms of the presence of non-smokers and smoking restrictions, as well as the presence of general social support Treatment-related beliefs, perceived social norms, and perceived behavioral control were slightly positive, and there was some evidence of improvement after intervention. As predicted by the Theory of Planned Behavior, beliefs about cessation treatment were correlated with intention to use cessation treatment. The rather lukewarm treatment beliefs in this group did not engender the use of smoking cessation treatments in the three months following intervention. Rather, in line with the more positive attitudes about cessation in general, the interventions stimulated quit attempts without treatment. Although prospective, population-based studies indicate that only about a fifth of quit attempts result in longer-term abstinence (Cooper et al., 2010), better understanding factors that contribute to quit attempts within particular populations can inform tailoring of future interventions and provide hypotheses for future testing. Although participants in this study did not experience large changes in beliefs and attitudes about cessation treatment after these brief interventions, improving perceptions about cessation treatment may lay the groundwork for future use of cessation treatment among those who do not quit.

Young people in particular are influenced by the behavior of their peers and role models (Cengelli, O’Loughlin, Lauzon, & Cornuz, 2012; LaRose, Leahey, Hill, & Wing, 2013; MacArthur, Harrison, Caldwell, Hickman, & Campbell, 2016). Indirect norms for cessation and using cessation treatment, represented here as “people would approve,” were mildly positive, improved after the interventions, and exhibited a trend for correlation with intention to use cessation medications and counseling. Notably, however, direct norms were not strong for using cessation treatment - less than half of participants reported that they knew someone who had used the three types of cessation treatments. Although baseline social support did not predict quitting activity, using social support was the most frequently reported quit aid, and 50% of those who attained verified abstinence did so by talking to a friend as a support to quit smoking. These data point to the potential for harnessing social norms and support to increase motivation and cessation activity among young adults with SMI – for example, by connecting young people to others who have successfully used cessation treatment.

Consistent with previous research in smokers with mental health conditions, higher feelings of stigma were associated with intention to quit and quit attempts in these young adult smokers with SMI (Brown-Johnson et al., 2015). While stigma is not a desired outcome of public health tobacco control activities, de-normalizing smoking may lead to perceived stigma, which in turn may stimulate cessation activity.

Although the brief, interactive, motivational intervention we developed was designed to motivate smokers to quit by using cessation treatment, very few of these young adult participants used verifiable treatment. This result aligns with previous studies in this population (Prochaska et al., 2015; Thrul & Ramo, 2017) demonstrating low engagement into cessation treatment after motivational intervention in young adults with and without SMI. Notably, participants who received this intervention were significantly more likely to become abstinent, and did so without using verified cessation treatment, as we have previously reported (Brunette et al., 2018). Due to the generally lower level of nicotine dependence and shorter history of smoking compared to older smokers (Brunette et al., 2017), brief interventions may stimulate effective quitting activity without additional formal cessation treatment. Such interventions warrant further study.

4.1. Limitations

This pilot study included small numbers by design, thus the results are exploratory, must be interpreted with caution and require replication. Although structural equation modeling would be ideal to test the relationship between Theory of Planned Behavior constructs, this study was not powered to use this statistical method. Additionally, while quit attempts may be one step in the process of quitting, quit attempts are not the same as sustained abstinence. However, we were able to provide a novel description of a geographically and racially diverse group of 58 young adult smokers with SMI, including their social context, predictors of quit attempts, and attitudes about cessation treatment, that have not previously been described.

4.2. Conclusion

These results confirm and extend previous work indicating that young adults with SMI have only modestly positive perceptions of evidence-based smoking cessation treatments. Brief interventions improved treatment beliefs somewhat, and beliefs were related to intentions to use cessation treatments, as predicted by the Theory of Planned Behavior. However, a substantial proportion of these young adults attempted to quit without formal evidence-based treatment, and a significant minority quit smoking completely after receiving the interactive/motivational intervention.

Highlights:

After brief intervention, a third of young adult smokers with SMI reported quit attempts.

Breath CO, intention to quit and symptom distress were related to quit attempts.

Attitudes and perceived behavioral control correlated with cessation treatment intention.

Beliefs about cessation treatment improved after the interactive intervention.

Intentions to use treatment remained low, in line with low use of treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Cancer Institute (NCI; U.S.A.) Grant number 5R21CA158863-02. NCI had no role in study design, conduct, data analyses or paper writing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: Brunette had funding to conduct research on schizophrenia and co-occurring alcohol use disorder from Alkermes.

Author Disclosure: Brunette had funding from Alkermes to conduct research on schizophrenia and co-occurring alcohol use disorder. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Agrawal A, Sartor C, Pergadia ML, Huizink AC, & Lynskey MT (2008). Correlates of smoking cessation in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Addict Behav, 33(9), 1223–1226. doi:S0306-4603(08)00093-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (2006, 2006). Constructing a TpB Questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations.

- Aschbrenner KA, Naslund JA, Gill L, Hughes T, O’Malley AJ, Bartels SJ, & Brunette MF (2017). Qualitative analysis of social network influences on quitting smoking among individuals with serious mental illness. J Ment Health, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1340600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M, Lawford BR, Burton SC, Heslop KR, Noble EP, Hausdorf K, & Young RM (2006). Smoking and schizophrenia: is symptom profile related to smoking and which antipsychotic medication is of benefit in reducing cigarette use? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Ahijevych K, Jarvis MJ, Hall S, LeHouezec J, Lichtenstein E, … Velicer W (2002). Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 4, 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, & Miller IW (1998). Reliability and Validity of Smoking Timeline Follow-Back Interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12(2), 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Johnson CG, Cataldo JK, Orozco N, Lisha NE, Hickman NJ 3rd, & Prochaska JJ (2015). Validity and reliability of the Internalized Stigma of Smoking Inventory: An exploration of shame, isolation, and discrimination in smokers with mental health diagnoses. Am J Addict, 24(5), 410–418. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette MF, Ferron JC, Ashbrenner KA, Coletti DJ, Devitt T, Harrington A, … Xie H (2017). Characteristics and predictors of intention to use cessation treatment among smokers with schizophrenia: Young adults compared to older adults. Journal of Substance Abuse and Alcoholism, 5(1), 1055. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette MF, Ferron JC, Robinson D, Coletti D, Geiger P, Devitt T, … McHugo GJ (2018. September 4). Brief Web-Based Interventions for Young Adult Smokers With Severe Mental Illnesses: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 20(10):1206–1214. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catchpole R,EH, McLeod SL, Brownlie EB, Allison CJ, & Grewal A (2017). Cigarette Smoking in Youths With Mental Health and Substance Use Problems: Prevalence, Patterns, and Potential for Intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 26(1), 41–55. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2016.1184600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2011). Quitting smoking among adults--United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 60(44), 1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cengelli S, O’Loughlin J, Lauzon B, & Comuz J (2012). A systematic review of longitudinal population-based studies on the predictors of smoking cessation in adolescent and young adult smokers. Tob Control, 21(3), 355–362. doi: 10.1136/tc.2011.044149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, & Kandel DB (1995). The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am J Public Health, 85(1), 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigarette Smoking: Health Risks and How to Quit (PDQ®)–Patient Version. (December 16, 2016). Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/quit-smoking-pdq

- Conrad KJ, Yagelka JR, Matters MD, Rich AR, Williams V, & Buchanan M, (2001), Reliability and validity of a modified Coloarado symptom index in a national homeless sample. Mental Health Services Research, 3(3), 141–153. doi: 10.1023/A:1011571531303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J, Borland R, Yong HH, McNeill A, Murray RL, O’Connor RJ, & Cummings KM (2010). To what extent do smokers make spontaneous quit attempts and what are the implications for smoking cessation maintenance? Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country survey. Nicotine Tob Res, 12 Suppl, S51–57. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Rosenheck RA, … Kane JM (2014). Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(12), 1350–1363. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBemardo RL, Aldinger CE, Dawood OR, Hanson RE, Lee SJ, & Rinaldi SR (1999). An E-mail assessment of undergraduates’ attitudes toward smoking. Journal of American College Health, 48(2), 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, & Sutherland I (2004). Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. Bmj, 325(7455), 1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Mueser KT, & McHugo GJ (1996). Clinician Rating Scales: Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), Drug Use Scale (DUS), and Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS) In Sederer LI & Dickey B (Eds.), Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice (pp. 113–116). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, Humair JP, Bergman MM, & Pemeger TV (2000). Development and validation of the Attitudes Towards Smoking Scale (ATS-18). Addiction, 95(4), 613–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K-O (1978). Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 3(3-4), 235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron JC, Brunette MF, McHugo GJ, Devitt TS, Martin WM, & Drake RE (2011). Developing a quit smoking website that is usable by people with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(2), 111–116. doi: 10.2975/35.2.2011.111.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, & Gerjo K (1996). The Theory of Planned Behavior: A review of its appications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11(2), 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grana RA, Ramo DE, Fromont SC, Hall SM, & Prochaska JJ (2012). Correlates of tobacco dependence and motivation to quit among young people receiving mental health treatment. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 125(1-2), 127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Hu MC, Schaffran C, & Kandel DB (2008). Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence among adolescents: findings from a prospective, longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 47(11), 1340–1350. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185d2ad [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett P, Fu SS, Nelson D, Clothier B, Saul JE, Widome R, … Burgess DJ (2017). A proactive smoking cessation intervention for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: Smoking-related stigma. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines D Young smokers’ attitudes about methods for quitting smoking: Barriers and benefits to using assisted methods. Addictive Behaviors, 21(4), 531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Davies M, & Kandel DB (2006). Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health, 96(2), 299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, & Graffunder CM (2016). Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(44), 1205–1211. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Russell MA, & Saloojee Y (1980). Expired air carbon monoxide: a simple breath test of tobacco smoke intake. Br Med J, 281(6238), 484–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahende J, Malarcher A, England L, Zhang L, Mowery P, Xu X, … Rolle I (2017). Utilization of smoking cessation medication benefits among medicaid fee-for-service enrollees 1999-2008. PLoS One, 12(2), e0170381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRose JG, Leahey TM, Hill JO, & Wing RR (2013). Differences in motivations and weight loss behaviors in young adults and older adults in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring), 21(3), 449–453. doi: 10.1002/oby.20053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST, & McDonald PW (2007). Youth smokers’ beliefs about different cessation approaches: are we providing cessation interventions they never intend to use? Cancer Causes Control, 18(7), 783–791. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9022-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucksted A, McGuire C, Postrado L, Kreyenbuhl J, & Dixon LB (2004). Specifying cigarette smoking and quitting among people with serious mental illness. American Journal on Addictions, 13(2), 128–138. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur GJ, Harrison S, Caldwell DM, Hickman M, & Campbell R (2016). Peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11-21 years: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Addiction, 111(3), 391–407. doi: 10.1111/add.13224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CD, May MG, Devine K, Smith S, DeHay T, & Mahalik J (2011). Multiple perspectives on tobacco use among youth with mental health disorders and addictions. American Journal of Health Promotion, 25(5 Suppl), S31–37. doi: 10.4278/aihp.100610-QUAL-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Conner M, & Bell R (1999). The Theory of Planned Behavior and smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 18(1), 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RJ, Rees VW, Rivard C, Hatsukami DK, & Cummings KM (2017). Internalized smoking stigma in relation to quit intentions, quit attempts, and current e-cigarette use. Substance Abuse, 38(3), 330–336. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2017.1326999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirie PI, Murray DM, & Luepker RV (1991). Gender differences in cigarette smoking and quitting in a cohort of young adults. (0090-0036 (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Prochaska JJ, Fromont SC, Ramo DE, Young-Wolff KC, Delucchi K, Brown RA, & Hall SM (2015). Gender differences in a randomized controlled trial treating tobacco use among adolescents and young adults with mental health concerns. Nicotine Tob Res, 17(4), 479–485. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking - 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shern DL, Wilson NZ, Coen AS, Patrick DC, Foster M, Bartsch DA, & Demmler J (1994). Client outcomes II: Longitudinal client data from the Colorado treatment outcome study. Milbank Q, 72(1), 123–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline Follow-Back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption In Litten RZ & Allen J (Eds.), Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods (pp. 41–72). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1996). Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) Users’ Manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg LI, Boyle RG, McCarty M, Asche SE, & Thoele MJ (2007). Young adult smokers: are they different? American Journal of Managed Care, 13(11), 626–632. doi:6788 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Galea S, Link B, & Xa G (2009). Stigma and Smoking: The Consequences of Our Good Intentions. Social Service Review, 83(4), 585–609. doi: 10.1086/650349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Galea S, & Link BG (2008). Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Soc Sci Med, 67(3), 420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh N, Vonk JM, & Boezen HM (2016). Lifetime Smoking History and Cause-Specific Mortality in a Cohort Study with 43 Years of Follow-Up. PLoS One, 11(4), e0153310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrul J, & Ramo DE (2017). Cessation Strategies Young Adult Smokers Use After Participating in a Facebook Intervention. Subst Use Misuse, 52(2), 259–264. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1223690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, & Klein DJ (2005). Predictors of attempted quitting and cessation among young adult smokers. Preventive Medicine, 41(2), 554–561. doi:S0091-7435(05)00024-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Carey KB, & Maisto SA (2003). Smoking among psychiatric outpatients: relationship to substance use, diagnosis, and illness severity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(4), 259–265. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.259 2003-09814-001[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, & McGorry PD (2006). Course of substance misuse and daily tobacco use in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res, 81(2-3), 145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, & Michie S (2010). Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(1), e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehring HJ, Liu F, McMahon RP, Mackowick KM, Love RC, Dixon L, & Kelly DL (2012). Clinical characteristics of heavy and non-heavy smokers with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res, 138(2-3), 285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Reutenauer EL, Allen TM, Termine A, Vessicchio JC, Sacco KA, … George TP (2007). Reliability of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale, and Tiffany Questionnaire for Smoking Urges in smokers with and without schizophrenia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86, 278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]