Abstract

Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP) controls growth by regulating the G1/S transition during cell cycle progression. Our genetic interaction studies show that TCTP fulfills this role by interacting with CSN4, a subunit of the COP9 Signalosome complex, known to influence CULLIN-RING ubiquitin ligases activity by controlling CULLIN (CUL) neddylation status. In agreement with these data, downregulation of CSN4 in Arabidopsis and in tobacco cells leads to delayed G1/S transition comparable to that observed when TCTP is downregulated. Loss-of-function of AtTCTP leads to increased fraction of deneddylated CUL1, suggesting that AtTCTP interferes negatively with COP9 function. Similar defects in cell proliferation and CUL1 neddylation status were observed in Drosophila knockdown for dCSN4 or dTCTP, respectively, demonstrating a conserved mechanism between plants and animals. Together, our data show that CSN4 is the missing factor linking TCTP to the control of cell cycle progression and cell proliferation during organ development and open perspectives towards understanding TCTP’s role in organ development and disorders associated with TCTP miss-expression.

Author summary

During organism development, the correct implementation of organs with unique shape, size and function, is the result of coordinated cellular processes, such as cell proliferation and expansion. Deregulation of these processes affect human health and can lead to severe diseases. While plants and animals have largely diverged in several aspects, some biological functions, such as cell proliferation, are conserved between these kingdoms. Previously we reported that the Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP), a highly-conserved protein among all eukaryotes, positively regulates cell proliferation and this role is conserved between plants and animals. In agreement with these data, animals TCTP was reported to highly accumulate in tumor cells, and thus represents a target for cancer research and therapies. To discover how TCTP regulates cell proliferation, we conducted studies to identify factors acting in the TCTP pathway. Using the model plant Arabidopsis, we identified that TCTP fulfil its role by interacting with CSN4, a subunit of the conserved COP9 complex. TCTP interferes with the role of COP9 to regulate the downstream complex CRL known to control cell proliferation in eukaryotes. We further demonstrate that this role is conserved in the fly Drosophila, thus corroborating the conservation of TCTP pathway between plants and animals. We believe that, the data here will provide exciting perspectives, beyond plant research, that will help understand developmental disorders associated with TCTP misfunction, such as cancer.

Introduction

The correct implementation of organs with unique shape, size and function is fundamental to the development of all multicellular organisms and is the result of coordinated cellular processes requiring key molecular actors. One such key player in eukaryotes is the Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP). TCTP was discovered in the 1980’s as a protein positively regulated at the translational level in many tumors [1,2]. TCTP is a highly-conserved protein found in all eukaryotes. TCTP was reported to be involved in several cellular processes, including cell proliferation, cell growth, malignant transformation, apoptosis and protection against various cellular stresses [3–8].

In plants as in animals, TCTP loss of function leads to embryonic lethality, because of slower cell cycle progression and reduced cell proliferation [6] and reduced cell proliferation associated with excessive cell death [9,10], respectively. The fact that TCTP loss of function is lethal demonstrates its major role in eukaryote development, but also hampered the full comprehension of its exact roles. By performing embryo rescue, we generated the first TCTP full knockout adult organism which allowed us to demonstrate that TCTP controls cell cycle progression by regulating G1/S transition and that this role is conserved between plants and animals [6]. However, how TCTP controls the G1/S transition and cell proliferation remains unknown in plants as in animals. To better understand such a role, we searched for TCTP interacting proteins and identified that TCTP interacts physically with CSN4, one of the eight subunits of the Constitutive Photomorphogenesis 9 (COP9) Signalosome (CSN), initially discovered in plants [11,12] and conserved in eukaryotes [13]. CSN regulates the activity, the assembly and/or subunits stability of CULLIN-RING ubiquitin Ligase (CRLs) complexes, a major class of the E3 ligase complexes in eukaryotes [14] involved in the polyubiquitination of proteins targeted to degradation [15]. The proper functioning of CRL has been shown to be absolutely required for various functions associated with the control of cell cycle, transcription, stress response, self-incompatibility, pathogen defense and hormones and light signaling [16–18].

CSN mainly regulates CLR activity through the removal of the post-translational modification RUB/NEDD8 (Related to UBiquitin/Neural Precursor Cell Expressed, Developmentally Down-Regulated 8) from its CULLIN (CUL) subunit [18]. The eight subunits of CSN are mandatory for the deneddylation activity [19–21].

Here, we show that TCTP interacts physically and genetically with CSN4 to control cell cycle progression. Our data demonstrate that downregulation of TCTP or CSN4 both leads to retarded G1/S transition, slower cell cycle progression and delay in plant development. Consistent with these data, knockout of TCTP is associated with increased CUL1 deneddylation. Conversely, over-accumulation of TCTP leads to accelerated cell cycle and plant development, associated with over-accumulation of neddylated CUL1. We also show that in Drosophila, the downregulation of dTCTP or dCSN4 is associated with defects in cell proliferation. Moreover, similar to our observations in plants, dTCTP downregulation is accompanied by increased CUL1 deneddylation. These data suggest that TCTP interacts with CSN4 and such interaction acts on the CUL1 neddylation status and affects CRL complex activity early during cell cycle progression influencing organ development both in plants and animals.

Results

TCTP and CSN4 interact physically and genetically to control growth

To gain insights into how TCTP controls cell cycle progression, we searched for its interacting proteins. Immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry (IP/MS) experiments were performed using protein extracts from Arabidopsis line expressing 35S::AtTCTP-GFP. Wild-type (WT) Col-0 and free-GFP-overexpressing plants lines (35S::GFP) served as controls. Among the proteins that co-immunoprecipitated with TCTP-GFP, but were absent in the control samples, we identified AtCSN4, a subunit of COP9 Signalosome, that was previously shown to be involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression [22]. To confirm this interaction, we generated line AtTCTPg-GFP that expresses a TCTP-GFP fusion under the control of its own promoter and line AtTCTPg-GFP/35S::AtCSN4-Flag, that, in addition, expresses AtCSN4-Flag under the control of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter (35S::AtCSN4-Flag). Anti-GFP antibody was used to immunoprecipitate the TCTP-GFP fraction from total proteins extracted from 10 days-old seedlings (S1A Fig), or from mature green seeds harvested from green siliques (S1B Fig).

The presence of CSN4 (46 kDa) was then revealed in the immunoprecipitated fraction. AtCSN4 was found in the AtTCTP-GFP enriched fraction from both 10 days-old seedlings and mature green seeds (S1A and S1B Fig, respectively). No trace of AtCSN4 was detected in WT Col-0 used as control and treated in parallel.

Next, we confirmed that endogenous AtCSN4 is able to co-immunoprecipitate with AtTCTP. For this, we performed immunoprecipitation on total proteins extracted from inflorescence of AtTCTPg-GFP and 35S::AtTCTP-GFP. As shown in Fig 1A, CSN4 co-immunoprecipitated with AtTCTP-GFP in both lines (Figs 1A and S1C). The interaction was further confirmed by pulling-down AtCSN4. Using plant lines 35S::AtCSN4-GFP, overexpressing AtCSN4, and 35S::AtCSN4-GFP/35S::AtTCTP, overexpressing both proteins, we show that TCTP co-immunoprecipitates with AtCSN4-GFP from both plant lines (Figs 1B and S1D).

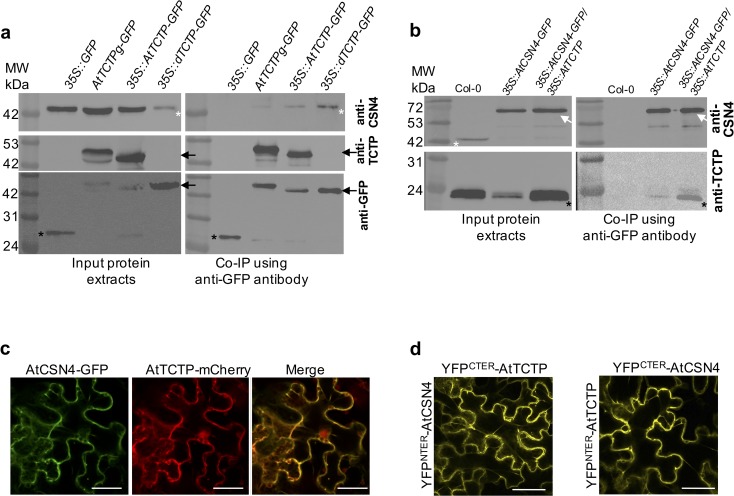

Fig 1. AtTCTP and AtCSN4 interact in vitro and in vivo.

(a) TCTP interacting proteins were co-immunoprecipitated from protein extracts prepared from inflorescences of 35S::GFP, AtTCTPg-GFP, 35S::AtTCTP-GFP and 35S::dTCTP-GFP/tctp plants using anti-GFP coupled magnetic beads. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-CSN4 (upper panel), anti-TCTP (middle panel) or anti-GFP (lower panel) antibodies. White asterisks: CSN4 protein; black arrows: TCTP-GFP protein; black asterisks: free GFP. (b) CSN4 interacting proteins were co-immunoprecipitated from protein extracts prepared from inflorescences of Col-0, 35S::AtCSN4-GFP and 35S::AtCSN4-GFP/35S::AtTCTP plants using anti-GFP coupled magnetic beads. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-CSN4 (upper panel) or anti-TCTP (lower panel) antibodies. White asterisks: CSN4 protein; white arrow: CSN4-GFP protein; black asterisks: TCTP protein. (c) AtCSN4-GFP (green) and AtTCTP-mCherry (red) co-localize in tobacco leaves. Bars: 50 μm. (d) Bimolecular Fluorescence complementation experiments in tobacco leaves show that AtTCTP and AtCSN4 fused with either C- or N-terminal YFP moieties, interact in vivo. Bars: 50 μm. As shown in S2 Fig, no signal was observed in the control BiFC assays in which AtTCTP or AtCSN4 fused with N- or C-terminal YFP moieties was co-infiltrated with an empty plasmid.

Finally, to address if Drosophila TCTP also interacts with CSN4, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using plant lines expressing Drosophila dTCTP in tctp knockout genetic background (line 35S::dTCTP-GFP). Previously we demonstrated that dTCTP was able to fully complement loss-of-function tctp [6]. As shown in Fig 1A, CSN4 co-immunoprecipitated with AtTCTP-GFP and also with dTCTP-GFP (Figs 1A and S1C), thus suggesting conservation of the TCTP/CSN4 interaction between plants and animals.

Next, we investigated the sub-cellular localization of CSN4 compared to TCTP. In agreement with co-immunoprecipitation data, co-expression of AtTCTP-mCherry and AtCSN4-GFP in tobacco leaf epidermal cells showed that these proteins co-localize in planta (Fig 1C). To further investigate AtTCTP-AtCSN4 interaction, we performed Bi-molecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC [23]) experiments by protein fusion to split YFP moieties and co-expression in tobacco cells. The data demonstrate that AtTCTP and AtCSN4 interact in planta (Fig 1D), confirming the co-immunoprecipitation results. Similar BiFC complementation results were obtained regardless if AtTCTP and AtCSN4 were fused to YFPCter or YFPNter (Fig 1D). BiFC experiments also showed that both AtTCTP and AtCSN4 were able to form homodimers (S2 Fig). However, the localization of AtTCTP-AtCSN4 heterodimer was distinct from that of the AtTCTP or AtCSN4 homodimers, thus corroborating TCTP-CSN4 in vivo interaction. No signal was observed when one of the vectors was empty (S2 Fig). Taken together these data demonstrate that AtTCTP and AtCSN4 interact physically in vivo.

To understand the biological significance of the AtTCTP-AtCSN4 interaction, we performed genetic interaction analyses using knockdown or overexpressor lines for both proteins. Previously, we showed that while AtTCTP knockout leads to embryo lethality, its down-regulation via RNAi (RNAi-AtTCTP lines) gave viable plants that nevertheless showed developmental defects [6]. Similar to plants mutants for AtTCTP, plants knockout for AtCSN4 showed severe developmental defects during early seed germination leading to seedling death in few days after germination (S3 Fig), thus in agreement with Dohmann et al. [22]. To overcome this difficulty, we generated knockdown plants via expression of a RNAi directed against AtCSN4 (line RNAi-AtCSN4). Western blot analyses confirmed the downregulation of AtTCTP and AtCSN4 in the corresponding RNAi lines (S4 Fig).

RNAi-AtCSN4 exhibited significant delay in rosette development compared to Col-0, thus a similar phenotype as RNAi-AtTCTP plants (Fig 2A–2C). Measurements of growing rosette diameters from 8 days post-germination until bolting, confirmed that these genotypes are impaired in development and that the difference in growth starts to be visible as early as 8 days after germination (Fig 2C). Similar to RNAi-AtTCTP plants, the inflorescence stems of AtCSN4-RNAi plants were shorter and the plants exhibited a dwarf phenotype (Figs 2B and S5). Additionally, RNAi-AtCSN4 plants had very short internodes between siliques resulting in a “bushy” plant phenotype (Figs 2B and S5).

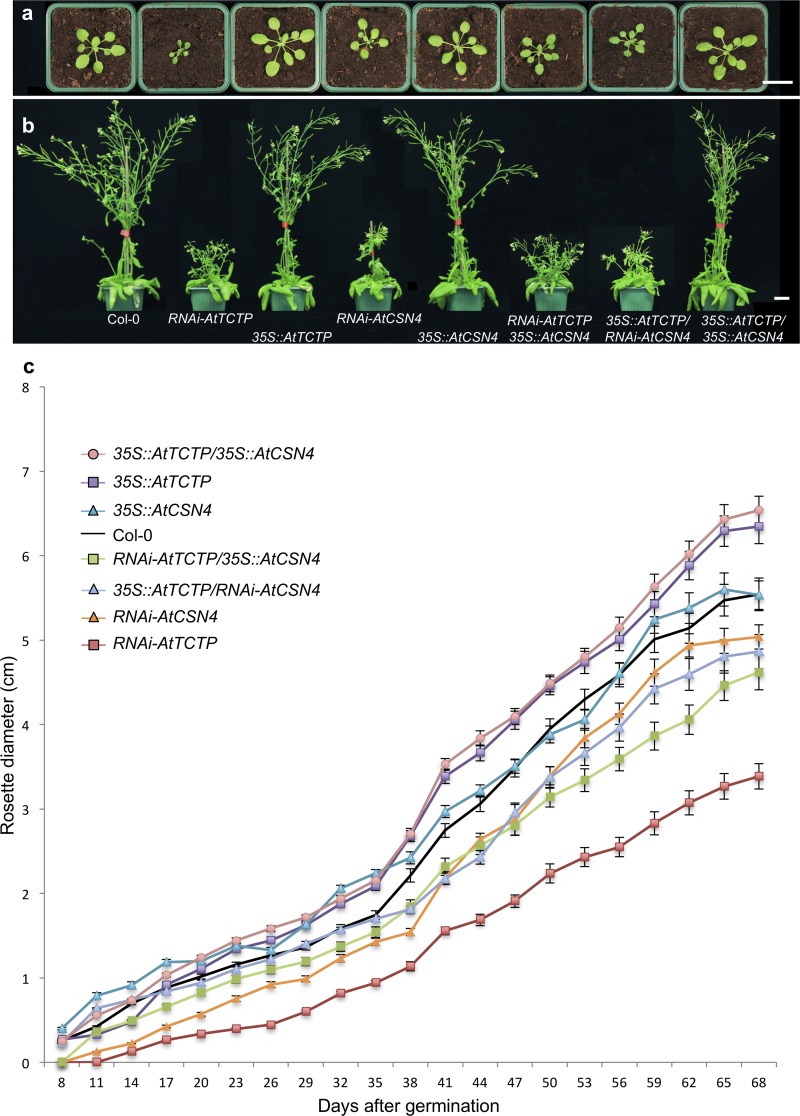

Fig 2. AtTCTP and AtCSN4 control plant development.

(a-b) Plants knockdown for CSN4 (RNAi-AtCSN4) exhibit a delay in development similar to that of RNAi-AtTCTP plants. RNAi-AtCSN4 or RNAi-AtTCTP plants overexpressing AtTCTP or AtCSN4, respectively, show similar phenotype as the simple RNAi lines. Pictures of plants were taken 59 days (a) and 92 days (b) after sowing. Bars: 2 cm. (c) Rosette diameter was measured from 8 days until 68 days after germination. The error bars represent standard errors. n = 18.

Plants overexpressing AtCSN4 (line 35S::AtCSN4) had normal development and adult plants had similar size as WT Col-0 plants (Fig 2). Plants overexpressing AtTCTP (line 35S::AtTCTP) exhibited accelerated growth and reached adult size earlier than the wild-type (Fig 2), in agreement with previously reported data [6]. The double overexpressor line (35S::AtCSN4/35S::AtTCTP) exhibited no additive effect and behaved as the single overexpressor line 35S::AtTCTP (Fig 2).

Crosses between RNAi-AtTCTP and AtCSN4 overexpressor lines on the one hand (line RNAi-AtTCTP/35S::AtCSN4) and between RNAi-AtCSN4 and AtTCTP overexpressor lines on the other hand (35S::AtTCTP/RNAi-AtCSN4), yielded plants with delayed growth compared to the WT, thus a phenotype similar to the single RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 knockdown plants, respectively (Fig 2A–2C). We should note that 35S::AtTCTP/RNAi-AtCSN4 plants grew a little slower than RNAi-AtCSN4, and RNAi-AtTCTP /35S::AtCSN4 plants grew a little faster than RNAi-AtTCTP plants. However, adult plants of the double transformant lines were indistinguishable from simple RNAi plants, demonstrating similar dwarf phenotype (Fig 2B). These data show that overexpression of AtTCTP or AtCSN4 could not compensate the developmental anomalies induced by knockdown of AtCSN4 or AtTCTP, respectively, and suggest that TCTP requires functional CSN4 to control growth. Despite several attempts, by plant genetic crossing or by genetic transformation, we were unable to generate the RNAi-AtTCTP/RNAi-AtCSN4 double knockdown line. It is likely that double TCTP/CSN4 knockdown leads to plant lethality.

AtTCTP and AtCSN4 regulate cell cycle progression and mitotic growth

To explore the cause of the growth defects observed in RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 plants, we analyzed cell division and cell expansion profiles. Previously, we demonstrated that downregulation of AtTCTP and the resulting decrease in plant organs size are correlated with reduced cell proliferation activity [6]. To explore if AtCSN4 down-regulation is also associated with defects in cell proliferation, we performed kinematic analysis of leaf growth on plantlets grown in vitro [6,24]. Previously, kinematic of leaf growth analyses demonstrated that downregulation of AtTCTP results in smaller leaves compared to the WT, due to slower cell proliferation [6]. Similarly, in line RNAi-AtCSN4 a significant reduction in leaf area was observed compared to the WT Col-0, starting from seven days after germination and the reduction was maintained during the whole observation period (Fig 3A). The reduction in leaf size correlated with about 20% decrease in cell number starting from day seven after germination and was maintained all along the observation period (Fig 3C), while no differences in cell size were observed (Fig 3B), thus again similar to RNAi-AtTCTP [6]. These data demonstrate that, similar to AtTCTP, the leaf growth defects associated with AtCSN4 knockdown (RNAi-AtCSN4) correlated with the decrease in cell number, while cell size remained unchanged.

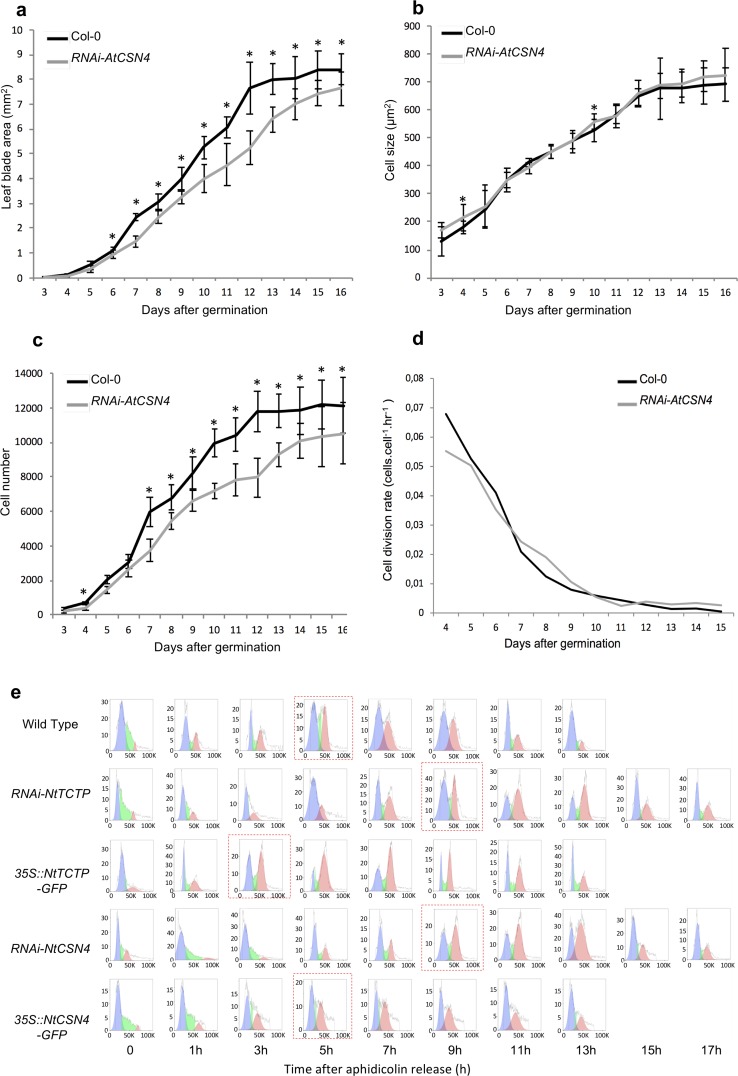

Fig 3. TCTP and CSN4 control cell proliferation and cell cycle progression.

Leaf blade area (a) and cell number per leaf (c) are reduced in RNAi-AtCSN4 plants compared to Col-0 WT due to a decrease in cell division rate (d). Cell size in developing leaves (b) of RNAi-AtCSN4 was the same as in Col-0 WT. n = 10; *: p-value <0,05. (e) Cell cycle progression at G1/S transition is slower in RNAi-NtCSN4 and RNAi-NtTCTP aphidicolin synchronized BY-2 cells compared to WT. The blue plots show cell population in G1 (2N), green plots are cells in S phase, and the red plots are cells in G2 (4N) phase.

Using the slope of the log 2–transformed number of cell per leaf [25], we calculated the cell division rate in RNAi-AtCSN4 plants. We observed that the cell division rate in RNAi-AtCSN4 was slower than in WT Col-0 plants (Fig 3D) in the early stage of leaf development where the cell division activity is higher [26]. Previously, we reported a similar tendency for RNAi-AtTCTP lines [6]. Determination of the number of newly produced cells per hour during leaf development showed that the lower cell division rate in RNAi-AtCSN4 line resulted in less newly produced cells at the beginning of leaf development (S6 Fig). Interestingly, the cell division rate was maintained at a higher level for longer time in the RNAi-AtCSN4, which indicates that a compensation mechanism likely exists. However, this was not enough to compensate the delay in leaf development, and therefore RNAi-AtCSN4 leaves stayed smaller than WT (Fig 3A). Later in leaf development, cell division in both plants was reduced to a very low level (Fig 3D).

We investigated root growth in both RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 lines. Similar to leaf growth, we also observed reduced root growth in developing seedlings of both lines (S7A Fig). Both RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 roots were shorter compared to WT starting as early as 3 days after germination (S7A Fig).

Similar to leaves and roots, petals of RNAi-AtCSN4 were also smaller in size compared to WT Col-0 (S7B Fig). The petal size reduction was associated with reduced cell number, thus a phenotype similar to that observed in RNAi-AtTCTP (S7B Fig) [6]. These data corroborate the results obtained in leaves and demonstrate that, like for AtTCTP, downregulation of AtCSN4 leads to reduced organ size as a result of altered cell proliferation. However, conversely to leaves, we observed that in petals of both RNAi-AtCSN4 and RNAi-AtTCTP the defects in cell proliferation were associated with an increase in cell size (S7B Fig), suggesting a compensation mechanism in the petals. AtTCTP overexpression (line 35S::AtTCTP) resulted in petals with increased size, but cell size was not affected, thus in agreement with Brioudes et al. [6]. AtCSN4 overexpression (line 35S::AtCSN4) did not affect petal development, (S7B Fig), thus corroborating the observed normal development of plants overexpressing AtCSN4 (Fig 2). Similar to observation during rosette development, overexpression of AtTCTP or AtCSN4 in RNAi-AtCSN4 and RNAi-AtTCTP, respectively, could not compensate for the petal developmental defects of the RNAi lines (S7B Fig). Line overexpressing both AtTCTP and AtCSN4 showed similar phenotype to 35S::AtTCTP (S7B Fig).

These data together show that the downregulation of AtCSN4 leads to slower cell proliferation associated with reduced organs size, thus a phenotype similar to that observed in AtTCTP mutant plants.

To further identify the origin of this reduced cell proliferation activity, we investigated cell cycle progression in tobacco BY-2 cells down-regulating or overexpressing NtCSN4 (line RNAi-NtCSN4 and 35S::NtCSN4, respectively) or NtTCTP (RNAi-NtTCTP, 35S::NtTCTP, respectively). Both, CSN4 and TCTP proteins accumulated at low levels in RNAi BY-2 cells and over-accumulated in overexpressor BY-2 cells, as demonstrated by Western blot analysis (S8 Fig).

Wild-type BY-2 cells and BY-2 cells under- or over-accumulating TCTP (RNAi-NtTCTP, 35S::NtTCTP) or CSN4 (RNAi-NtCSN4, 35S::NtCSN4) were synchronized using aphidicolin. Cell cycle progression was followed every 2 hours after aphidicolin release (AAR) using flow cytometry (Fig 3E). Normal progression of cell cycle over time was observed in wild-type BY-2 cells with rapid reduction of G1 cells (2N) and a concomitant increase of G2 cells (4N) over the first 5 hours AAR, followed by a decrease of G2 cells with mitosis ending at about 13h AAR. In agreement with previously reported data [6], the G1/S transition in RNAi-NtTCTP BY-2 cells occurred with 4 hours delay compared to the wild-type and this delay was maintained all along the cell cycle (Fig 3E). Similarly, RNAi-NtCSN4 BY-2 cells also showed a slower cell cycle progression with about the same 4 hours delay at the G1/S transition compared to wild-type BY-2 cells (Fig 3E). Like for RNAi-NtTCTP, the 4 hours delay of cell cycle progression in RNAi-NtCSN4 was maintained until the end of the cell cycle, thus corroborating the kinematic of growth data obtained in Arabidopsis leaves (Fig 3).

These data together demonstrate that the downregulation of either NtTCTP or NtCSN4 leads to comparable delays in cell cycle progression and that such delay occurs at G1 and/or early S phase.

Conversely to BY-2 cells knockdown for NtTCTP, BY-2 cells overexpressing NtTCTP (35S::NtTCTP) entered G1/S transition about 2 hours earlier than wild-type BY-2 (Fig 3E). However, these cells completed their first cell cycle the same time as WT BY-2 cells, at 13h AAR. This indicates that 35S::NtTCTP BY-2 cells has longer S or M2 phase to compensate faster G1. In agreement with the absence of cell proliferation and developmental defects in 35S::AtCSN4 Arabidopsis line (Figs 2 and S7B), no significant difference in cell cycle progression was observed in 35S::NtCSN4 BY-2 cells, compared to the wild-type (Fig 3E).

To further explore at which step of the cell cycle TCTP and CSN4 precisely act and to confirm BY-2 results directly in planta, we performed cumulative EdU labeling in the root tips of the different Arabidopsis lines to estimate S-phase length and total cell cycle length. Results show that, similar to observations in BY-2 cells, total cell cycle length in root tips was increased by 4 hours, both in RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 lines, while S-phase length remained unchanged (Table 1). Likewise, no substantial changes were observed in cell cycle length in 35S::AtTCTP and 35S::AtCSN4 lines (Table 1), again consistent with the results obtained in BY-2 cells (Fig 3C). Interestingly, S-phases lengths again remained unchanged, suggesting that the observed cell cycle slow-down after the rapid progression through G1/S phase seen in 35S::NtTCTP BY2 cells, did not affect S-phase but probably G2/M phase.

Table 1. TCTP and CSN4 does not control S-phase length during cell cycle progression.

| Cell Cycle Length (h) | Confidence Interval 95% | S-phase length (h) | Confidence Interval 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Col-0 | 15 | [13,5–16] | 1,5 | [0,6–2,4] |

| RNAi-AtTCTP | 18** | [16,8–20] | 1,5 | [0,5–2,3] | |

| RNAi-AtCSN4 | 19*** | [16,5–23,2] | 1,9 | [0,4–3,9] | |

| 35S::AtTCTP | 15 | [13,5–15,8] | 1,7 | [0,9–2,5] | |

| 35S::AtCSN4 | 15 | [13,5–15,8] | 1,5 | [0,53–2,2] | |

| 2 | Col-0 | 15 | [13,6–15,9] | 2,8 | [0,9–3,1] |

| RNAi-AtTCTP | 19*** | [16,4–20,3] | 2,7 | [0,8–3,2] | |

| RNAi-AtCSN4 | 19*** | [16,5–23,1] | 2,8 | [1–3,7] | |

| 35S::AtTCTP | 15 | [13,5–16] | 2,8 | [0,9–3,8] | |

| 35S::AtCSN4 | 15 | [12,8–16,1] | 2,7 | [0,8–3,7] |

EdU incorporation in Arabidopsis root tips demonstrated in both RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 lines cell cycle duration is about 4h longer compared to Col-0 WT. Note that the length of S-phase was not affected in any of these lines. Data show results of two independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001).

All these data together with the TCTP-CSN4 co-immunoprecipitation and the in vivo interactions studies suggest that TCTP and CSN4 interact physically to control G1/S transition during cell cycle progression.

TCTP/CSN4 interaction impact CUL1NEDD8 /CUL1 ratio in plants and animals

CSN4 is one of the eight subunits of the CSN that regulates CRL activity via the post-translational RUB/NEDD8 modification of its CUL subunit. To investigate the biological significance of AtTCTP/AtCSN4 interaction, we evaluated the neddylation status of the Arabidopsis CULLIN1 (CUL1), a major target of CSN. Using an antibody against CUL1, we were able to distinguish free CUL1 and the neddylated CUL1 (CUL1NEDD8) forms (Figs 4A–4C and S9A–S9C).

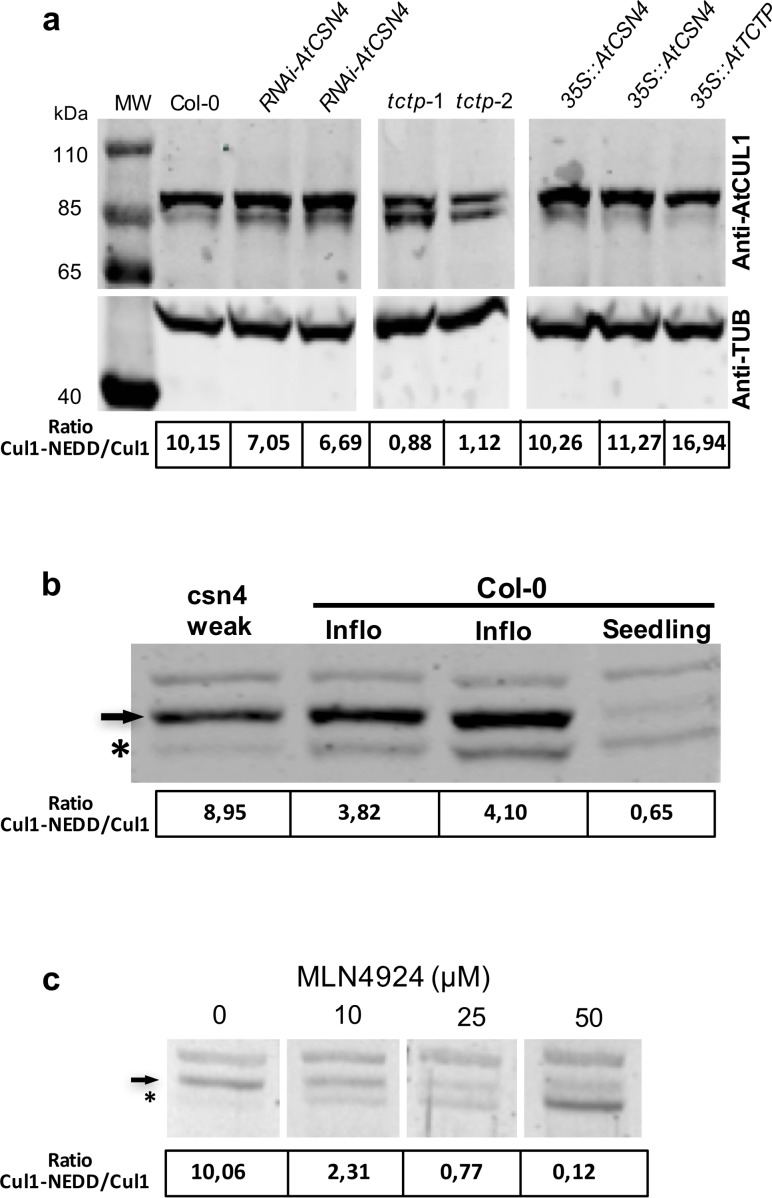

Fig 4. The CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio is modified in Arabidopsis tctp mutants.

(a) CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio decreases in a similar manner in the two independent tctp knockout lines, tctp-1 and tctp-2, while in plants overexpressing AtTCTP (35S::AtTCTP) increased CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio was observed. (b) CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio in inflorescence and seedlings of Col-0 WT plants and in inflorescence of weak mutant of csn4. (c) Treatment of WT Col-0 with MLN4924, a drug that inhibits neddylation, results in an increase of the free CUL1 form with concomitant decrease of the CUL1NEDD8 form, confirming that the observed bands correspond to CUL1 at different neddylation status. CUL1 protein was detected by Western blot using anti-CUL1 antibody. Quantifications of CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio are shown under each lane. Anti-TUB is shown as control. Star: free CUL1; Arrow: CUL1NEDD8 form.

By growing plants on medium with increasing concentrations of MLN4924, a drug that inhibits CUL neddylation [27], we confirmed that the observed protein bands indeed correspond to CUL1 and CUL1NEDD8 (Figs 4C and S9C). In WT plants, we observed about 8–10 times more CUL1NEDD8 than free CUL1 while at 50μM MLN4924 we observed that almost all CUL1 were non-neddylated (Figs 4C and S9C). Moreover, we demonstrate that WT inflorescence contains more neddylated CUL1, while in WT seedlings non-neddylated CUL1 is more present (Figs 4B and S9B). Inflorescence of a weak mutant of csn4 contains almost exclusively neddylated CUL1 (Fig 4B) in accordance with previous results [28].

Next, CUL neddylation status was analyzed in two independent tctp knockout lines (tctp-1 and tctp-2), in 35S::AtTCTP, RNAi-AtCSN4 and 35S::AtCSN4 (Figs 4A and S9A). For both tctp-1 and tctp-2, we observed a drastic decrease (Fig 4A) to complete absence (S9A Fig) of the CULNEDD8, with a concomitant increase of free CUL1, leading to a drop in CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio in knockout lines (Figs 4A and S9A). Overexpression of AtTCTP led to a slight increase in CUL1NEDD8 (Fig 4A) in agreement with the fact that although 35::AtTCTP plants grow faster, fully adult plants showed a phenotype similar to the wild-type [6] (Fig 2). These data suggest a role for AtTCTP in the regulation of CUL1 neddylation status, which in turn influences the activity of CRL complexes. Only small changes of CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio were observed in RNAi-AtCSN4 plants (Fig 4A). This is likely due to the fact that flowers already accumulated high level of neddylated CUL1 (Fig 4B) and that in RNAi-AtCSN4 lines we do not have full obliteration of AtCSN4 (S4A and S4B Fig).

In 35S::AtCSN4, no decrease of CUL1NEDD8 was observed and the CUL1 neddylation status was similar to wild-type (Fig 4A). This is in agreement with previous studies showing that overexpression of only one subunit of the COP9 complex does not modify its deneddylation activity [29]. The data also corroborate the fact that CSN4 overexpression does not affect cell cycle progression as well as organ and plant development (Figs 2 and 3E and S7).

We demonstrated that CUL1 neddylation is affected in tctp mutants, suggesting that CRLs function in general might be affected. The best characterized SCF/CRL in Arabidopsis is SCFTIR1 implicated in auxin perception and signaling [30,31]. Therefore, we investigated if auxin responses are affected in tctp mutant. Auxin homeostasis reporter DR5rev::GFP and auxin efflux reporter PIN1::PIN1-GFP [32] were introgressed into tctp knockout plants. Similar to WT embryos, in tctp embryos PIN1::PIN1-GFP accumulated in apical cell lineage at globular and transition stage, then at heart stage the pattern switches to a PIN1 localization in the future cotyledons and across the provasculature (S10A Fig). In agreement with these data, in tctp mutant embryos the accumulation pattern of auxin homeostasis reporter DR5rev::GFP was similar to that of WT embryos. Moreover, the accumulation pattern of auxin homeostasis reporter DR5rev::GFP in response to exogenous treatment with synthetic auxin 2,4D was also similar in WT and tctp embryos (S10B Fig). These data show that the modification in CUL1 neddylation associated with AtTCTP mutation do not affect the auxin pathway nor the signaling via SCFTIR1, indicating that the role of TCTP-CSN4 interaction in regulating CUL neddylation and CRL activity is specific to cell cycle.

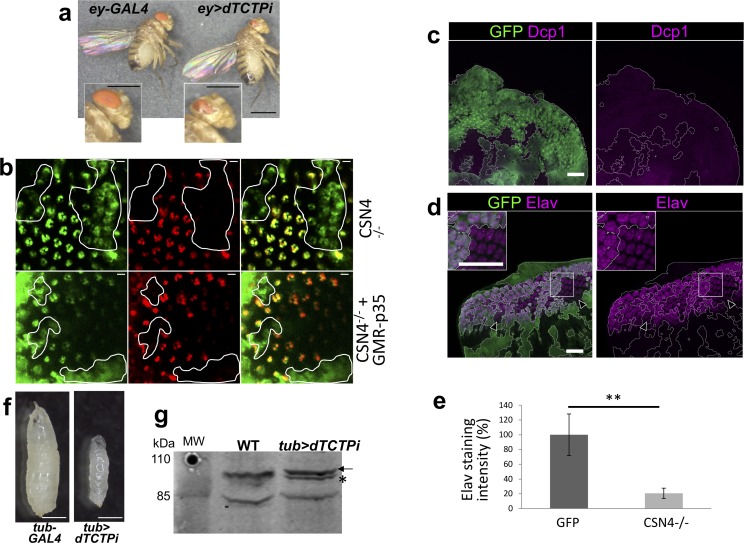

Previously, we demonstrated that the role of TCTP in regulating cell proliferation was conserved between plants and animals. Furthermore, we demonstrated that AtCSN4 is able to interact with dTCTP (Figs 1A and S1C). Therefore, we investigated if the TCTP-CSN4 pathway has similar roles in Drosophila development as observed in plants. Using the UAS/GAL4 system [33], first, we generated flies in which the expression of dTCTP was silenced via the expression of a dTCTP RNAi under the control of the eye-specific promoter eyless (line ey>dTCTPi). eyless promoter drives gene expression in the eye imaginal disk anterior to the furrow at the time when eye cell progenitors are actively dividing [34]. Interference with dTCTP using the eyless promoter led to a significant size reduction of the eye, in agreement with Brioudes et al [6] (Fig 5A).

Fig 5. The role of TCTP and CSN4 in the control of CULLIN neddylation and cell proliferation is conserved in Drosophila.

(a) Downregulation of dTCTP specifically in the eyes (ey>dTCTPi) of Drosophila leads to small eye phenotype. Close up images of wild type adult eye and of eye expressing ey>dTCTPi are shown (Bars = 500 μm). (b) Drosophila adult retina visualized by immersion microscopy with the Tomato/GFP-FLP/FRT method. CSN4 mutant clones are visualized by the expression of Rh1-GFP and by the absence of tomato (red) and are delineated by a white line. Photoreceptors are visualized by Rh1-GFP (Left panels), Rh1-tdTomato (Middle panels) or in the merge (Right panels). Photoreceptor absence is indicated by loss or diffuse GFP fluorescence in CSN4k08018 mutant clones (CSN4-/-, upper panels). CSN4k08018 mutant clones in which p35 is overexpressed (CSN4-/-, lower panels) still show loss or diffuse GFP staining in mutant clone. Bars = 5μm. (c-e) CSN4 mutant photoreceptors show a delay in the acquisition of neuronal identity but not in caspase staining. Third instar eye imaginal discs carrying dCSN4-/- mutant clones visualized by the lack of GFP (green) Bars = 25 μm. (c) eye imaginal discs stained with anti-Dcp-1 (purple) show no increase of staining in dCSN4-/- mutant clones. (d) Eye imaginal discs stained with anti-Elav show a delay of expression (arrowheads) at the morphogenetic furrow and a reduced level in dCSN4-/- mutant clones. (e) Quantification of Elav staining in (d) shows significant reduction in dCSN4-/- mutant clones compared to wild type (GFP) (n = 5; p < 0,01). (f) Downregulation of dTCTP in all tissues of Drosophila larvae (tub>dTCTPi) leads to developmental arrest with reduced size and subsequent larval lethality at the first instar larvae. 7 days after egg-laying, control larvae (tub-GAL4) are at third instar (left) while tub>dTCTPi larvae stay at first instar (right). Bars = 500 μm. (g) Impaired larval development is associated with a decrease of the CUL1NEDD8 abundance in the tub>dTCTPi compared to tub-GAL4. Star: free CUL1; Arrow: CUL1NEDD8 form.

To study the role of CSN4 in the Drosophila eye, we used the P-element recessive lethal lines CSN4k08018 from the UCLA URCFG collection. Previous analysis of CSN4k08018reported a rough eye associated with loss of photoreceptor and patterning defects [35,36]. To further analyze the loss of dCSN4 function, we used the mosaic Tomato/GFP-FLP/FRT method in combination with the caspase inhibitor p35 [36,37]. In this system, the absence of red fluorescence (tdTomato) marks dCSN4-/- mutant photoreceptors in a background where all photoreceptors express GFP in the adult Drosophila eye. This method allowed the observation of mosaic eyes, in which regions where the dCSN4 gene have been inactivated can be detected by the absence of the tomato reporter (Fig 5B, middle panel). dCSN4 inactivation led to a strong loss of photoreceptors as seen by the lack or diffuse GFP staining in dCSN4-/- mutant clones of Drosophila adult retina (Fig 5B, left panel). Importantly, no effector caspase (dcp-1, death caspase-1) staining was detected in dCSN4-/- mutant clones in third instar eye discs (Fig 5C). Moreover the loss of photoreceptor in dCSN4-/- mutant clones was not rescued by the expression of the caspase inhibitor p35 (Fig 5B, lower panels), a protein that prevents apoptosis [38]. This indicates that the loss of photoreceptors in dCSN4-/- mutant clones is not due to increased apoptosis but rather impaired proliferation as in dTCTP mutants.

Next, we examined the expression of the neuronal marker ELAV, which is progressively acquired in differentiating photoreceptor posterior to the morphogenetic furrow in third instar eye discs [34]. We observed a delay and a reduction of ELAV staining in dCSN4-/- mutant clones compared to wild type (Fig 5D and 5E). The delay in the acquisition of ELAV marker in dCSN4-/- mutant clones could be the consequence of a delay in the proliferation of dividing photoreceptor progenitors as previously described in dachsund mutant that allows a tight coordination of proliferation and differentiation [39].

To explore whether the effect of TCTP on CUL1 neddylation is also conserved between plants and animals, we investigated CUL1 neddylation in Drosophila knockdown for dTCTP under the control of TUBULIN constitutive promoter (line tub>dTCTPi). Interference with dTCTP under the TUBULIN constitutive promoter (tub>dTCTPi) led to severe larval developmental defects and to growth arrest after the first larvae instar (Fig 5F). We evaluated the CUL1 neddylation status in tub>dTCTPi larvae knockdown for dTCTP exhibiting severe developmental delay, as compared to the wild-type flies and we observed a drastic decrease of the CULNEDD8 with a concomitant increase of free CUL1 (Fig 5G). These data strongly suggest that, like in Arabidopsis, knockdown of dTCTP or dCSN4 led to impaired cell proliferation. Moreover, knockdown of dTCTP in Drosophila also affects CUL1 neddylation status in a similar manner than in Arabidopsis, suggesting a conserved role of TCTP in the control of CUL neddylation between plants and animals. Importantly, the fact that AtCSN4 interacts with dTCTP (Fig 1C) suggests that, similar to plant AtTCTP, Drosophila dTCTP controls CUL1 neddylation likely via its interaction with CSN4.

Discussion

In plants and in animals, TCTP is known to be implicated in many cellular processes, but its mode of action is largely unknown. Previously, we demonstrated that in Arabidopsis and in Drosophila, TCTP has a conserved role in the control of organ growth by regulating cell proliferation. We showed that TCTP regulates cell cycle progression more specifically at the G1/S transition [6]. To gain insight into the pathway by which TCTP fulfills this function, we identified its interactors in Arabidopsis. Here, we establish a functional relationship between TCTP and CSN4, one of the eight subunits of the COP9 Signalosome, a complex conserved among eukaryotes [12].

Like tctp null mutants, csn4 mutants are not viable [22] (and this study). We therefore analyzed partial loss-of-function lines using RNAi. Both RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 Arabidopsis lines display dwarf phenotype and reduced organ size due to decreased cell proliferation, and more specifically to a delay in the G1/S transition as evidenced by tobacco BY-2 cell synchronization and EdU incorporation assays in Arabidopsis root meristematic cells.

The ability of AtTCTP and AtCSN4 to interact and the similarity of the phenotypes of RNAi lines suggest that they could function in the same pathway, which was corroborated by our genetic analyses. No additive phenotypic effect was observed in the double overexpressor and the down-regulation of AtCSN4 was epistatic on AtTCTP overexpression, and reciprocally, AtCSN4 overexpression did not fully rescue the developmental defects of RNAi-AtTCTP plants. However, we observed that although the RNAi-AtTCTP plants that overexpress AtCSN4 exhibited delayed development compared to the wild-type, they grew faster than RNAi-AtTCTP plants. This could be due to the fact that CSN4 is likely involved in other biological process required for plant development, separately from AtTCTP [40]. We were unable to generate RNAi-AtTCTP/RNAi-AtCSN4 double knockdown line, likely because these plants are not viable. This could be due to the fact that both simple RNAi lines are only partially loss of function, and that simultaneous down-regulation of AtTCTP and AtCSN4 leads to defects comparable to what is observed in tctp or csn4 knockout lines. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that AtTCTP and AtCSN4 could also be separately involved in several other biological processes required for plant development [3,4,6,40]. This is supported by the fact that AtTCTP and AtCSN4 proteins are not always co-localized in the cell (Fig 1C). Thus, TCTP/CSN4 interaction is most likely required at a defined time points during cell proliferation, but both proteins have additional functions independently of their interaction.

Using synchronized BY-2 cells and EdU incorporation assays, we determined that both RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 present similar delays at the G1/S transition, reinforcing the idea that the two proteins act in the same pathway. On the other hand, adding more AtTCTP leads to accelerated cell cycle progression. The fact that no effect on cell cycle progression was observed in plants over-accumulating AtCSN4, suggests that AtTCTP is likely the limiting factor to control cell cycle progression in the AtTCTP-AtCSN4 pathway.

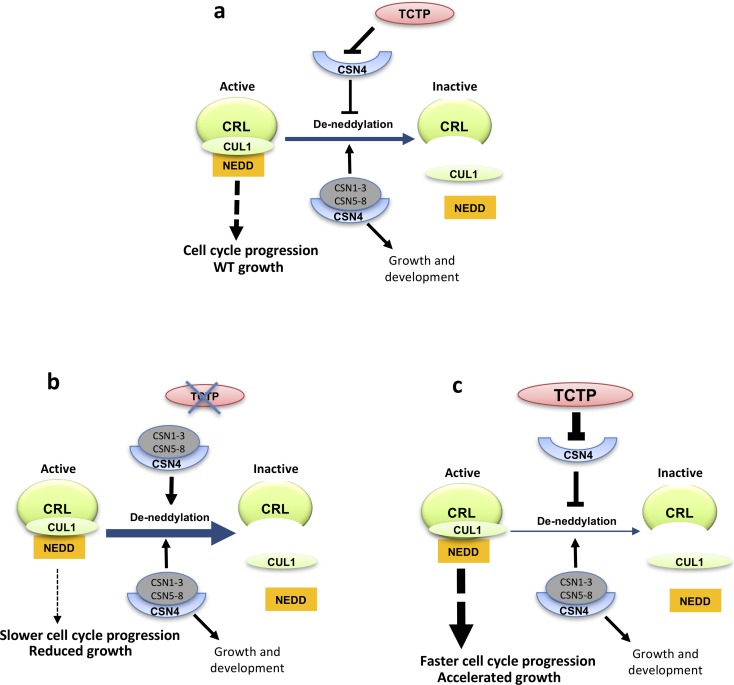

CSN4 is part of the COP9 complex known to control CRL via neddylation status of their CULLINS (CUL) subunits [17]. We therefore asked whether TCTP and CSN4 might control CUL neddylation status. Indeed, we observed that both AtTCTP and dTCTP misexpression strongly impacts CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio supporting an elegant hypothesis relative to how TCTP controls G1/S transition. In fact, it is conceivable that via its interaction TCTP could sequester CSN4, preventing its association with the COP9 complex specifically at the G1/S transition. It is well established that the lack of one of the eight COP9 sub-units is sufficient to suppress the deneddylation activity [19,20,30,41]. Moreover, in Drosophila it was previously reported that during development, CSN4 functions to maintain self-renewal of stem cells, and the switch from self-renewal to differentiation requires the sequestration of CSN4 from the CSN by the protein Bam [42]. Another subunit, CSN5 was also demonstrated to be sequestered by the small protein Rig-G, in order to negatively regulate SCF-E3 ligase activity in mammalian cells [43]. We can thus imagine that a similar scenario exists between TCTP and CSN4 to drive cell cycle through the G1/S transition and maintain cell proliferation. This is the first time that a sequestration mechanism to regulate CSN activity is described in plants.

This model is also consistent with the phenotypic defects triggered by TCTP deficiency (Fig 6). Franciosini et al. [44] suggested that during embryo maturation COP9 became deactivated, and subsequently reactivated at germination. It is possible that the role of TCTP during embryogenesis is to sequester CSN4 and prevent assembly and activity of COP9 complex during the G1/S transition. Moreover, it was demonstrated that CUL1 neddylation is increased during normal embryo development, thus the reduced neddylation in tctp embryos could explain their delayed development and death [6,44].

Fig 6. Model showing the interaction of TCTP and CSN4 and its impact on CUL neddylation and CRL complex and growth.

(a) Wild type situation. (b) Mutation of TCTP leads to enhanced deneddylation of CUL and inactivation of CRL, resulting in slower cell cycle progression and reduced growth. (c) The inverse is observed when TCTP is overexpressed. Other pathways involving CUL neddylation via CSN are not shown. CSN1-3 and CSN5-8: subunits of the Cop9 complex forming the active COP9 complex when associated with CSN4.

To our surprise, although AtCSN4 down-regulation induced severe developmental defects, we were not able to detect strong modification in CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio in RNAi-AtCSN4 lines. This is probably due to the fact that CUL1NEDD8 level is already too high in the inflorescence to see a small increase due to reduced level of CSN4 accumulation and also to additional functions of CSN4 [16,18,40] independently of its interaction with TCTP. Also, because the CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 homeostasis is known to be highly dynamical process that is strictly regulated during plant development [44], it is possible that AtCSN4 down-regulation in our RNAi lines is not strong enough to have measurable CUL1NEDD8 ratio changes at the studied developmental stages. However, we assumed that the developmental phenotypes observed in this line were due to compromised COP9 complex function. Indeed, previous work on dominant negative, weak alleles or RNAi lines of different CSN subunits demonstrated that the developmental defects, similar to those observed in our RNAi-AtCSN4 line, were due to disturbance of CSN activity [28,31,41,44].

TCTP down-regulation leads to a decrease of the CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio. Since CSN4 is involved in the deneddylation of CULs, its down-regulation would be expected to increase this ratio, as described in csn4 mutant [22]. TCTP and CSN4 thus appear to act antagonistically on CULs neddylation, and one could therefore expect RNAi-AtCSN4 and RNAi-AtTCTP lines to display opposite phenotypic defects instead of the similarities we report here. However, the effect of neddylation on CRLs activity is extremely complex: csn mutants that produce more neddylated CUL are expected to increase CRL activity resulting in positive effect on development. However, all csn mutants are delayed in their development. On the other hand, treatment of plants with MLN924, a drug that inhibits neddylation resulting in the accumulation of deneddylated CUL1, also leads to plant lethality [27], thus a similar phenotype as when TCTP is mutated. It is now well established that in addition to the CULNEDD8/CUL ratio, the temporal kinetics of CUL and NEDD8 association/dissociation controls CRL activity [45–48]. Indeed, to be fully active, CRLs need to undergo a cycle of neddylation and de-neddylation [14,49] and inactivation of factors with opposite roles on this cycle can thus result in the same cellular defects. On the other hand, CRL acts both on positive and negative cell cycle regulators and the timing of the degradation of these regulators has to be tightly coordinated [16]. Thus, opposite perturbation of CRL activity by TCTP or CSN4 downregulation can lead to similar phenotypes.

Together, our results provide evidence for the role of TCTP and CSN4 in the control of cell cycle regulation via the modification of CUL1 neddylation status that affects CRL activity (summarized in Fig 6). However, the nature of the CRLs and their targets that account for this role on cell cycle regulation remains to be established.

In plants, the mechanisms controlling the G1/S transition are poorly known. However, it seems that there are close similarities compared to animals. Indeed, overexpression of CKI results in G1 arrest of the cell cycle in plants [50]. Furthermore, ICK2/KRP2, a CKI related protein, and other central cell cycle regulators such as E2Fc, a central transcription factor controlling G1/S transition in plants, must be degraded via the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway to allow the cells to go through the G1/S transition [51,52]. Although it was suggested that AtCSN4 is implicated in the G2/M transition [22], it has also been reported that G1/S phase specific core cell cycle genes were overexpressed in csn4 mutant [22,53]. Furthermore, in human cells, it was reported that the downregulation of different CSN subunits can affect cell cycle in opposite ways, and the resulting perturbation of COP9 activity affect both G1/S and G2/M transition [54]. These published data suggest that CSN is likely equally important for G1/S and G2/M transitions in both plants and animals, and thus corroborate our findings here. They are also consistent with the fact that CUL deneddylation affects the activity of multiple CRL complexes.

Our data show that TCTP regulates G1/S transition, in agreement with Brioudes et al [6]. It is likely that TCTP/CSN4 interaction is specifically interfering with CSN function at G1/S. In this scenario, TCTP controls cell cycle through sequestration of CSN4, leading to CSN assembly impairment that in turn impacts neddylation status and stability of CRL complexes. CRLs have major role in several biological processes, among which hormone transduction and signaling are well studied [17]. The fact that no changes were observed in auxin flux and homeostasis in tctp knockout embryo during development is in favor of the conclusion that TCTP/CSN4 interaction likely controls CRLs specifically involved in cell cycle control but not in auxin signaling. It was reported that perturbation of CUL neddylation do not necessarily affect the activity of all CLRs. In mice, deletion of CSN8 did not affect SCF/CRL function in general, as a subset of CRLs maintained their capacity to degrade their substrate [55]. Similarly, in Drosophila csn4 and csn5 mutants, some but not all SCF/CRLs implicated in circadian rhythm maintenance are affected [56]. Therefore, it is likely that in tctp embryos, only a specific subset of CRLs implicated in cell cycle progression is affected, resulting in arrest of development, while auxin signaling remains normal. This is also supported by the fact that conversely to tctp, auxin signaling mutants are able to complete embryo development and produce mature seeds [57].

Previously, we demonstrated that TCTP function in the regulation of cell proliferation is conserved between plants and animals [6]. Arabidopsis AtTCTP and Drosophila dTCTP share only 38% amino acids identity, but many of the essential amino acids and domains known to be required for TCTP functions are conserved between plant and animal TCTPs [3,6]. Previously we showed that AtTCTP and dTCTP were able to homodimerize, but also to dimerize with each other in vivo [6], thus another argument that despite the overall relatively divergent protein sequences, their function is conserved. In support of a conservation and importance of TCTP/CSN4 interaction in animals, we show that, similar to dTCTP loss of function, dCSN4 loss of function result in a loss of photoreceptors in adult Drosophila retina accompanied by a delayed acquisition of neuronal identity, which requires a tight coordination with cell proliferation in the developing eye disc. Furthermore, we show that, like for AtTCTP, down-regulation of Drosophila dTCTP also led to a decrease of CUL1NEDD8. Moreover, co-immunoprecipitation results show that dTCTP is able to interact with AtCSN4, which indicates that TCTP/CSN4 interaction is likely conserved between plants and animals.

In summary, our data provide evidences that TCTP functions as a key growth regulator by controlling cell proliferation together with CSN4. We propose that TCTP could sequester CSN4 to control CUL1 neddylation status and thus CRL activity (Fig 6), and this role is conserved between plants and animals. These data add a new piece to resolve the puzzle of developmental biology processes by connecting two evolutionary conserved pathways, TCTP and COP9, for cell proliferation. Our work will help future studies to better understand growth disorders and malignant transformation, associated with TCTP miss-expression.

Materials and methods

Constructs, plant biological material and growth conditions

T-DNA insertion knockout lines tctp-1 (SAIL_28_C03), tctp-2 (GABI_901E08) as well as the RNAi-AtTCTP, 35S::AtTCTP, 35S::AtTCTP-GFP, 35S::dTCTP-GFP and the AtTCTPg-GFP lines harboring the AtTCTP genomic sequence including the promoter region, exons, introns, and the 3′ UTR region in which the GFP was inserted in frame with AtTCTP (At3g16640), have been previously described [6]. csn4 knockout line (Salk_043720C) was provided by NASC. The weak allele mutant of AtCSN4 was kindly provided by C. Bellini (Umea University, Sweden).

AtCSN4-RNAi lines: The DNA fragment corresponding to the ORF of AtCSN4 (At5g42970) without start codon ATG was cloned into the vector pB7GWIWG2D(II) [58] under the control of the CaMV 35S constitutive promoter. The resulting construct was then used to transform A. thaliana Col-0 plants. Lines are referred to as RNAi-AtCSN4.

AtCSN4-GFP overexpressing line: The DNA fragment corresponding to the ORF of AtCSN4 was cloned into the pK7WGF2 [58] under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Lines are referred to as 35S::AtCSN4.

The above lines were then crossed to generate the 35S::AtTCTP/RNAi-AtCSN4, the 35S::AtCSN4/RNAi-AtTCTP and the 35S::AtTCTP/35S::AtCSN4 lines.

AtTCTPgGFP/35S::AtCSN4-Flag line: The DNA fragment corresponding to the ORF of AtCSN4 was cloned into pEarleyGate202 vector containing Flag motif [59]. The resulting construct was then used to transform Arabidopsis line AtTCTPg-GFP that harbors pTCTP::TCTPg-GFP construct [6].

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as the wild-type (WT) for all experiments.

Embryo rescue of homozygous tctp-1 and tctp-2 embryos was performed as described previously [6]. During all steps, embryos from wild type siliques were used as control.

PIN1::PIN1-GFP/TCTP+/- and DR5rev::GFP/TCTP+/- were generated by crossing tctp-2+/- with PIN1::PIN1-GFP or DR5rev::GFP, respectively. Embryo from white seeds and green seeds were then isolated [6] and observed under LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss). In vitro culture of Arabidopsis embryo and hormone treatments with 2,4D were performed as previously described [60].

All seedlings were grown in culture chambers under shorts-day condition (8h/16h day/night at 22°C/19°C) for 4 weeks, then transferred to long-day condition (22°C, 16h/8h light/dark) to promote flowering, with light intensity of 70 μEm-2 sec-1.

Fly analyses

All flies were maintained on standard corn/yeast medium at 25°C.

eyless>dTCTPi line: Expression of dTCTPi was carried out using the GAL4/UAS expression system [33]. We crossed eyless-GAL4 line (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) with UAS::dTCTPi [10] and analyzed the F1 adult progeny.

tub>dTCTPi line: Expression of dTCTPi was carried out using the GAL4/UAS expression system. We crossed tub-GAL4 line (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) with UAS::dTCTPi [10] and analyzed the F1 larvae.

We generated dCSN4 mosaic clones in the eye using Tomato/GFP-FLP/FRT method [36,37]. The following fly strains were used: P{neoFRT}42D P{lacW}CSN4k08018/CyO (Kyoto Center), ey-FLP; FRT42D, Rh1-tdTomato[ninaC]/CyO; GMR-p35,Rh1-GFP/TM6B and ey-FLP; FRT42D, Rh1-tdTomato 94.1/CyO; UAS-GFP. Living adult flies were anesthetized using CO2 and embedded in a dish containing 1% agarose covered with cold water, as described [37] and imaged using a Leica SP5 upright confocal microscope using a water immersion objective. Photoreceptors were marked by Rh1-GFP or Rh1-tdTomato.

Mosaic clones were also generated using ey-FLP; FRT42D Ubi-GFP and eye discs analyzed at third instar larvae as previously described [61]. Dissected eye discs were stained with a rat anti-ELAV (Developmental Hybridoma Bank, 1/10) or anti-Dcp-1 (Cell Signaling, 1/300) and a rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen, 1/400) and imaged using a LSM800 Zeiss confocal microscope.

BY-2 cell lines

RNAi-NtTCTP and 35S::NtTCTP-GFP BY-2 cell lines have been described previously [6].

RNAi-NtCSN4 and 35S::NtCSN4-GFP BY-2 cell lines: DNA corresponding to NtCSN4 ORF was amplified using primers BY2-CSN4-F (CACCATGGAGAGTGCGTTCGCTAGTG) and BY2-CSN4-R (CTAGACAGGAATAGGGAGCCCCTTCT) and cloned into the vector pK7GWIWG2 or pK7WGF2, respectively [58]. The resulting constructs were used to transform tobacco BY-2 (N. tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow-2) cell suspension as previously described [62]. BY-2 cells were grown in the dark at 25°C constant temperature and with agitation at 150 rpm.

Cell cycle synchronization of BY-2 cells and DNA content analyses

BY-2 cells were synchronized using aphidicolin (Sigma) as previously described [6]. Samples were collected every two hours and flow cytometry analyses were performed essentially as previously described [6]. Fluorescence intensity of stained nuclei was measured with MACSQuant VYB flow cytometer (BD Bioscience), using 405nm excitation blue laser. DNA content analysis was performed using FlowJo,LLC software version 10.

EdU incorporation assay

Seeds of the relevant lines were germinated on half strength MS. Five days after germination, plantlets were transferred to EdU (10 μM, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented medium and harvested after 3h, 6h, 9h and 12h of incubation. Experiments were performed as described [63]. The percentage of EdU positive nuclei increases linearly with time, and follows an equation that can be written as P = at + b where P is the percentage of EdU positive nuclei and t is time. Total cell cycle length is estimated as 100/a, and S phase length is b/a. The parameters of the equation and their confidence intervals were estimated with the R statistics software using the least-square method.

Plant and organ growth analyses

Kinematic of leaf growth was performed as previously described [24] on the two first initiated-leaves of Col-0 WT and RNAi-AtCSN4 plants grown in vitro. Leaf size as well as number and size of abaxial epidermal cells were determined starting of day 3 and until day 16 after germination. The average cell division rates were determined by calculating the slope of the Neperian Logarithmic-transformed number of cells per leaf, which was done using five-point differentiation formulas [25]. The number of newly produced cells were calculated by 72h time period.

Rosette diameter was determined starting of 8 days after germination, until bolting. Rosette area was measured every 3 days with a caliper. Each measure was performed using 18 plants for each genotype. Experiments were performed on two independent transformation events and in three biological replicates.

To investigate root growth, seeds were germinated on half strength MS and 5 day-old plantlets were transferred to a new plate and grown vertically for 6 days. Root length of each plant was measured using the Fiji software at day 0, 3 and 6 after transfer.

Petal area, petal cell number and size measurements were performed as previously described [64]. Briefly, petals were cleared overnight in a solution containing 86% ethanol and 14% acetic acid followed by two incubations of 4h each in ethanol 86%. Petals were dissected and photographed using Leica MZ12 stereomicroscope. Cells from cleared petals were observed with a Nikon Optiphot 2 microscope with Nomarski optics. Petal area and cell density i.e. number of cells per surface unit, were determined from digital images using ImageJ software (U. S. National Institutes of Health).

Proteins interactions in planta

Co-localization experiments: cDNA fragments corresponding to the coding sequences of AtTCTP and AtCSN4 were PCR amplified and then fused to RFP and GFP, respectively. Resulting constructs were used to infiltrate leaf epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana plants as previously described [65].

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) experiments: cDNA fragments corresponding to the coding sequences of AtTCTP and AtCSN4 were PCR amplified and then cloned into the pBiFP1, pBiFP2, pBiFP3 and pBiFP4 vectors [66] using the Gateway technology. Resulting constructs were used to infiltrate leaf epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana plants as previously described [65]. BiFC was observed four days post-infiltration using a LSM 710 Confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments using AtTCTP-GFP or AtCSN4-GFP as bait were performed using the μMACS GFP Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Three biological replicates were performed for each sample. Wild-type Col-0 and 35S::GFP plants were used as controls. Tissues of 10 days-old seedlings, mature seeds harvested from green siliques or inflorescences were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using mortar and pestle. The tissue powder (200 mg) was resuspended with 1ml pre-cooled (4°C) Miltenyi lysis buffer complemented with one tablet of cOmplete Mini EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) for 5 ml of lysis buffer. Cellular extracts were incubated on ice 10 min and then centrifuged 10 min at 21 000g (4°C). The supernatants were incubated with 50μl anti-GFP antibody coupled to magnetic μMACS microbeads for specific isolation of GFP-tagged protein during 1 hour at 4°C on orbital shaker. Microbeads were bound to magnetic columns and washed as described by the manufacturer, before elution of GFP-tagged proteins and bound proteins. Eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blot. For the immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry (IP/MS) we visualized proteins by silver staining of the SDS-PAGE gel (ProteoSilver Plus Silver Stain Kit, SIGMA).

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Tissue (plants or cell culture) were grinded and total proteins were extracted using « Plant Total Protein Extraction Kit » (Sigma).

Protein from Drosophila larvae were extracted using approximately 10 larvae in 100 μl of protein extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES pH:7,5, 100 mM KCl, 5% Glycerol, 10 mM EDTA, 0,1% Tween, 1 μM DTT, 1 μM PMSF, 5 μl/ml Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma), 5 μl/ml Phosphatase Inhibitor (Sigma)). After centrifugation for 10 min at 160000 g, proteins contained in the supernatant were dosed using Bradford method[67].

Proteins were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies directed against AtTCTP (1/500 dilution) [6], AtCUL1 (1/2000 dilution; Enzo LifeScience), dCUL1 (1/500 dilution; Thermo Scientific), AtCSN4 (1/2000 dilution; Enzo LifeScience), Flag (1/1000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich); α-Tubulin (1/1000 dilution; Sigma) or GFP (1/2000 dilution; Roche). IRDye 800CW and IRDye 680RD (1/10 000 dilution; LI-COR) were used as secondary antibodies and the signal was revealed using Odyssey Clx imaging system and signal intensity was quantified using the Image Studio Lite software (LI-COR). HRP conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies (1/5000 dilution) and the signal was revealed using Clarity Western ECL substrate and the ChemiDocTouch imaging system (Biorad). Intensity of the bands was quantified using ImageJ software (U. S. National Institutes of Health).

Supporting information

(a-c) TCTP interacting proteins were co-immunoprecipitated from protein extracts prepared from seedlings (a) or from mature green seeds (b) of AtTCTPg-GFP/35S::AtCSN4-Flag plants, and from inflorescences (c) of 35S::GFP, AtTCTPg-GFP (two independent lines 1 & 2), 35S::AtTCTP-GFP and 35S::dTCTP-GFP/tctp (two independent lines 1 & 2) plants, using anti-GFP coupled magnetic beads. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-Flag (a, lower panel; b, left panel), anti-GFP (a, upper panel; c, lower panel), anti-TCTP (c, middle panel) or anti-CSN4 (b, right panel; c, upper panel) antibodies. Red asterisks: CSN4 protein; white arrows: CSN4-Flag protein; black arrows: TCTP-GFP protein; black asterisks: free GFP.

(d) CSN4 interacting proteins were co-immunoprecipitated from protein extracts prepared from inflorescences of Col-0, 35S::GFP and 35S::AtCSN4-GFP plants using anti-GFP coupled magnetic beads. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-CSN4 (upper panel), anti-TCTP (middle panel) or anti-GFP (lower panel) antibodies. Red asterisks: CSN4 protein; white arrows: CSN4-GFP protein; blue arrows: TCTP protein; black arrows: TCTP-GFP protein; black asterisks: free GFP.

(TIF)

(a) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays show that AtTCTP or AtCSN4 fused with N- and C-terminal YFP moieties are able to form homodimers. No signal was observed in the control assays in which AtTCTP or AtCSN4 fused with N- or C-terminal YFP moieties was co-infiltrated with an empty plasmid (b, c; respectively).

(TIF)

Wild type Col-0 and csn4 seedlings grown in light (a) or dark (b) show severe developmental delay. Plants at 10 days after germination are shown. csn4 seedlings grown in dark show no hypocotyl elongation (b), confirming the constitutive photomorphogenesis phenotype. Bars = 500μm.

(TIF)

AtCSN4 (a,b) and of AtTCTP (c,d) protein accumulation was assessed by Western blot in the different plant lines downregulated and/or overexpressor of AtCSN4 or AtTCTP.

Relative AtCSN4 or AtTCTP accumulation in the different plant lines was determined compared to accumulation in the WT Col-0 (= 1). Values are shown under each lane.

Black arrow indicates AtCSN4-GFP. Red arrow indicates endogenous AtCSN4. Blue arrow: AtTCTP. *: α-Tubulin (TUB) was used as loading control.

(TIF)

RNAi-AtCSN4 and RNAi-AtTCTP plants exhibit similar dwarf phenotype of flower stem with short internodes. Bars = 1cm.

(TIF)

The number of newly produced cells per hour was reduced in RNAi-AtCSN4 plants compared to Col-0 WT. The number of newly produced cells was determined by 72h period. The error bars represent standard errors. n = 10; *: p-value <0,05.

(TIF)

(a) RNAi-AtTCTP and RNAi-AtCSN4 plants exhibit reduced root growth compared to the wild-type (Col-0). Root length was measured at day 5, 8 and 11 days after germination. Values are average +/- standard error (n = 30 for RNAi-AtTCTP and n = 20 for RNAi-AtCSN4). Asterisks indicate statistically relevant differences (T-test; p-value <0.01).

(b) Compared to the WT, mature petals of lines tctp, RNAi-AtTCTP, RNAi-AtCSN4, RNAi-AtTCTP/35S::AtCSN4 and 35S::TCTP/RNAi-AtCSN4 are reduced in size with increased cell size, suggesting lower cell division rate.

Conversely, mature petals of lines overexpressing AtTCTP (lines 35S::AtTCTP) and the double overexpressor 35S::AtTCTP/35S::AtCSN4 are larger in size while cell size was unaffected or smaller, respectively, compared to Col-0. This suggest increased cell division rate in these lines. The stars indicate significant differences relative to the WT Col-0 (T-test; p-value < 0,001).

(TIF)

Western blot assay to evaluate the accumulation of NtTCTP (a) and NtCSN4 (b) in WT BY-2 tobbacco cells, and in BY-2 cells knockdown and overexpressor for these genes.

The relative accumulation of NtTCTP and NtCSN4 based on Western blot data is shown under each lane. Black arrows indicate GFP fused proteins (NtTCTP-GFP or NtCSN4-GFP). Red arrows indicate endogenous NtTCTP and NtCSN4 proteins.

(TIF)

(a) CUL1 neddylation is decreased in tctp mutants. Three independent samples (1–3) were analyzed using two independent tctp knockouts (tctp-1 and tctp-2). (b) CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio in inflorescence and seedlings of Col-0 plants. (c) Treatment with MLN4924, a drug that inhibits neddylation, results in an increase of the free CUL1 form with concomitant decrease of the CUL1NEDD8 form, confirming that the observed two bands correspond to neddylated and non neddylated CUL1. CUL1 protein was detected by Western blot using anti-CUL1 antibody. Quantification of CUL1NEDD8/CUL1 ratio is shown under each lane. Star: CUL1. Arrow: CUL1NEDD8.

(TIF)

(a) PIN1::PIN1-GFP localization in tctp knockout embryos is similar to that in WT embryos, indicating that auxin efflux is not disturbed by tctp loss-of-function. Embryos at globular, transition and heart stages are shown. Bars: 2 0μm.

(b) The accumulation of GFP, expressed under the control of synthetic auxin response DR5rev promoter, is not disturbed in tctp mutant embryos compared to WT embryos, indicating that auxin transduction pathway is not disturbed by tctp loss-of-function. Exogenous treatment with synthetic auxin, 2,4-D leads to similar expansion of DR5rev-GFP expression in tctp mutant and WT embryos. Bars = 20 μm.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexis Lacroix, Justin Berger and Patrice Bolland (RDP-ENS-Lyon) for plant handling. We thank C. Bellini (Umea University, Sweden) for providing the csn4 weak allele mutant seeds. We acknowledge the contribution of SFR Biosciences (UMS3444/CNRS, US8/Inserm, ENS de Lyon, UCBL) facilities: PLATIM microscopy facility for confocal imaging assistance, the ARTHRO-TOOLS fly facility, Cytometry facility and Protein Science facility. We thank Veronique Barateau for assistance with the FACS experiments.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by funds from the French “Agence Nationale de la Recherche” grants ANR-09-BLAN-0006 and ANR- 13-BSV7-0014, by the “Biologie et Amélioration des Plantes” Department of the French “Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique”, by the “Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon”, by Rijk Zwaan company and by the CIFRE program of the ANRT. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chitpatima S.T., Makrides S., Bandyopadhyay R. & Brawerman G. Nucleotide sequence of a major messenger RNA for a 21 kilodalton polypeptide that is under translational control in mouse tumor cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16, 2350 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas G., Thomas G. & Luther H. Transcriptional and translational control of cytoplasmic proteins after serum stimulation of quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78, 5712–6 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betsch L., Savarin J., Bendahmane M. & Szecsi J. Roles of the Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP) in Plant Development. Results Probl Cell Differ 64, 149–172 (2017). 10.1007/978-3-319-67591-6_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bommer U.A. Cellular function and regulation of the translationally controlled tumour protein TCTP. The Open Allergy Journal 5, 19–32. (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bommer U.A. & Thiele B.J. The translationally controlled tumour protein (TCTP). Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36, 379–85 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brioudes F., Thierry A.M., Chambrier P., Mollereau B. & Bendahmane M. Translationally controlled tumor protein is a conserved mitotic growth integrator in animals and plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 16384–9 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1007926107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Susini L. et al. TCTP protects from apoptotic cell death by antagonizing bax function. Cell Death Differ 15, 1211–20 (2008). 10.1038/cdd.2008.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thayanithy V. Evolution and expression of translationally controlled tumour protein (TCTP) of fish. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 142, 8–17 (2005). 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S.H. et al. A knockout mouse approach reveals that TCTP functions as an essential factor for cell proliferation and survival in a tissue- or cell type-specific manner. Mol Biol Cell 18, 2525–32 (2007). 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu Y.C., Chern J.J., Cai Y., Liu M. & Choi K.W. Drosophila TCTP is essential for growth and proliferation through regulation of dRheb GTPase. Nature 445, 785–8 (2007). 10.1038/nature05528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serino G. et al. Arabidopsis cop8 and fus4 mutations define the same gene that encodes subunit 4 of the COP9 signalosome. Plant Cell 11, 1967–80 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei N. & Deng X.W. The COP9 signalosome. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19, 261–86 (2003). 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.112449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barth E., Hubler R., Baniahmad A. & Marz M. The Evolution of COP9 Signalosome in Unicellular and Multicellular Organisms. Genome Biol Evol 8, 1279–89 (2016). 10.1093/gbe/evw073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lydeard J.R., Schulman B.A. & Harper J.W. Building and remodelling Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. EMBO Rep 14, 1050–61 (2013). 10.1038/embor.2013.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teixeira L.K. & Reed S.I. Ubiquitin ligases and cell cycle control. Annu Rev Biochem 82, 387–414 (2013). 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060410-105307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genschik P., Marrocco K., Bach L., Noir S. & Criqui M.C. Selective protein degradation: a rheostat to modulate cell-cycle phase transitions. J Exp Bot 65, 2603–15 (2014). 10.1093/jxb/ert426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hotton S.K. & Callis J. Regulation of cullin RING ligases. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59, 467–89 (2008). 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.104011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwechheimer C. & Isono E. The COP9 signalosome and its role in plant development. Eur J Cell Biol 89, 157–62 (2010). 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busch S. et al. An eight-subunit COP9 signalosome with an intact JAMM motif is required for fungal fruit body formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 8089–94 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0702108104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohmann E.M., Kuhnle C. & Schwechheimer C. Loss of the CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC9 signalosome subunit 5 is sufficient to cause the cop/det/fus mutant phenotype in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 1967–78 (2005). 10.1105/tpc.105.032870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharon M. et al. Symmetrical modularity of the COP9 signalosome complex suggests its multifunctionality. Structure 17, 31–40 (2009). 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dohmann E.M. et al. The Arabidopsis COP9 signalosome is essential for G2 phase progression and genomic stability. Development 135, 2013–22 (2008). 10.1242/dev.020743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohad N., Shichrur K. & Yalovsky S. The analysis of protein-protein interactions in plants by bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant Physiol 145, 1090–9 (2007). 10.1104/pp.107.107284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Veylder L. et al. Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 1653–68 (2001). 10.1105/TPC.010087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erickson R.O. Modeling of Plant Growth. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 27, 407–434 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnelly P.M., Bonetta D., Tsukaya H., Dengler R.E. & Dengler N.G. Cell cycling and cell enlargement in developing leaves of Arabidopsis. Dev Biol 215, 407–19 (1999). 10.1006/dbio.1999.9443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakenjos J.P. et al. MLN4924 is an efficient inhibitor of NEDD8 conjugation in plants. Plant Physiol 156, 527–36 (2011). 10.1104/pp.111.176677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacurar D.I. et al. The Arabidopsis Cop9 signalosome subunit 4 (CNS4) is involved in adventitious root formation. Sci Rep 7, 628 (2017). 10.1038/s41598-017-00744-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dessau M. et al. The Arabidopsis COP9 signalosome subunit 7 is a model PCI domain protein with subdomains involved in COP9 signalosome assembly. Plant Cell 20, 2815–34 (2008). 10.1105/tpc.107.053801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dohmann E.M., Levesque M.P., Isono E., Schmid M. & Schwechheimer C. Auxin responses in mutants of the Arabidopsis CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC9 signalosome. Plant Physiol 147, 1369–79 (2008). 10.1104/pp.108.121061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwechheimer C. et al. Interactions of the COP9 signalosome with the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCFTIRI in mediating auxin response. Science 292, 1379–82 (2001). 10.1126/science.1059776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benkova E. et al. Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115, 591–602 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brand A.H. & Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–15 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mollereau B. & Domingos P.M. Photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila: from immature neurons to functional photoreceptors. Dev Dyn 232, 585–92 (2005). 10.1002/dvdy.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J. et al. Discovery-based science education: functional genomic dissection in Drosophila by undergraduate researchers. PLoS Biol 3, e59 (2005). 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gambis A., Dourlen P., Steller H. & Mollereau B. Two-color in vivo imaging of photoreceptor apoptosis and development in Drosophila. Dev Biol 351, 128–34 (2011). 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dourlen P., Levet C., Mejat A., Gambis A. & Mollereau B. The Tomato/GFP-FLP/FRT method for live imaging of mosaic adult Drosophila photoreceptor cells. J Vis Exp, e50610 (2013). 10.3791/50610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hay B.A., Wolff T. & Rubin G.M. Expression of baculovirus P35 prevents cell death in Drosophila. Development 120, 2121–9 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bras-Pereira C. et al. dachshund Potentiates Hedgehog Signaling during Drosophila Retinogenesis. PLoS Genet 12, e1006204 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei N., Serino G. & Deng X.W. The COP9 signalosome: more than a protease. Trends Biochem Sci 33, 592–600 (2008). 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serino G. & Deng X.W. The COP9 signalosome: regulating plant development through the control of proteolysis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 54, 165–82 (2003). 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan L. et al. Protein competition switches the function of COP9 from self-renewal to differentiation. Nature 514, 233–6 (2014). 10.1038/nature13562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu G.P. et al. Rig-G negatively regulates SCF-E3 ligase activities by disrupting the assembly of COP9 signalosome complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 432, 425–30 (2013). 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franciosini A. et al. The COP9 SIGNALOSOME Is Required for Postembryonic Meristem Maintenance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant 8, 1623–34 (2015). 10.1016/j.molp.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choo Y.Y. et al. Characterization of the role of COP9 signalosome in regulating cullin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol Biol Cell 22, 4706–15 (2011). 10.1091/mbc.E11-03-0251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cope G.A. & Deshaies R.J. COP9 signalosome: a multifunctional regulator of SCF and other cullin-based ubiquitin ligases. Cell 114, 663–71 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denti S., Fernandez-Sanchez M.E., Rogge L. & Bianchi E. The COP9 signalosome regulates Skp2 levels and proliferation of human cells. J Biol Chem 281, 32188–96 (2006). 10.1074/jbc.M604746200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peth A., Berndt C., Henke W. & Dubiel W. Downregulation of COP9 signalosome subunits differentially affects the CSN complex and target protein stability. BMC Biochem 8, 27 (2007). 10.1186/1471-2091-8-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosadeghi R. et al. Structural and kinetic analysis of the COP9-Signalosome activation and the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase deneddylation cycle. Elife 5(2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jasinski S. et al. The CDK inhibitor NtKIS1a is involved in plant development, endoreduplication and restores normal development of cyclin D3; 1-overexpressing plants. J Cell Sci 115, 973–82 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.del Pozo J.C., Boniotti M.B. & Gutierrez C. Arabidopsis E2Fc functions in cell division and is degraded by the ubiquitin-SCF(AtSKP2) pathway in response to light. Plant Cell 14, 3057–71 (2002). 10.1105/tpc.006791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verkest A., Weinl C., Inze D., De Veylder L. & Schnittger A. Switching the cell cycle. Kip-related proteins in plant cell cycle control. Plant Physiol 139, 1099–106 (2005). 10.1104/pp.105.069906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menges M., de Jager S.M., Gruissem W. & Murray J.A. Global analysis of the core cell cycle regulators of Arabidopsis identifies novel genes, reveals multiple and highly specific profiles of expression and provides a coherent model for plant cell cycle control. Plant J 41, 546–66 (2005). 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y. et al. Anti-tumor effect of germacrone on human hepatoma cell lines through inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol 698, 95–102 (2013). 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menon S. et al. COP9 signalosome subunit 8 is essential for peripheral T cell homeostasis and antigen receptor-induced entry into the cell cycle from quiescence. Nat Immunol 8, 1236–45 (2007). 10.1038/ni1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]