Abstract

Objectives. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with SSc. The submaximal heart and pulmonary evaluation (step test) is a non-invasive, submaximal stress test that could be used to identify SSc patients with PH. Our aims were to determine whether change in end tidal carbon dioxide () from rest to end-exercise, and the minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production ratio (), both as measured by the step test, differ between SSc patients with and without PH. We also examined differences in validated self-report questionnaires and potential PH biomarkers between SSc patients with and without PH.

Methods. We performed a cross-sectional study of 27 patients with limited or dcSSc who underwent a right heart catheterization within 24 months prior to study entry. The study visit consisted of questionnaire completion; history; physical examination; step test performance; and phlebotomy. , , self-report data and biomarkers were compared between patients with and without PH.

Results. SSc patients with PH had a statistically significantly lower median (interquartile range) than SSc patients without PH [−2.1 (−5.1 to 0.7) vs 1.2 (−0.7 to 5.4) mmHg, P = 0.035], and a statistically significantly higher median (interquartile range) [53.4 (39–64.1) vs 36.4 (31.9–41.1), P = 0.035]. There were no statistically significant differences in self-report data or biomarkers between groups.

Conclusion. and as measured by the step test are statistically significantly different between SSc patients with and without PH. and may be useful screening tools for PH in the SSc population.

Keywords: scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, pulmonary hypertension, end tidal carbon dioxide, submaximal exercise testing, right heart catheterization

Rheumatology key messages

SSc patients with pulmonary hypertension had lower delta end tidal carbon dioxide than those without.

SSc patients with pulmonary hypertension had higher minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production ratio than those without.

Submaximal exercise testing may be useful in the evaluation of SSc patients for pulmonary hypertension.

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH), defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ⩾25 mmHg on right heart catheterization (RHC) [1], is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with SSc [2–4]. Patients with SSc can develop PH as the result of left heart disease or interstitial lung disease (ILD), or they can have pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)—or some combination thereof. Although RHC is the gold standard diagnostic test for PH, it is an expensive and invasive test [5–9]. Therefore, non-invasive methods of screening and monitoring for PH are often employed, such as transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with Doppler and serial pulmonary function testing. However, these non-invasive tests are limited in their ability to distinguish SSc patients with PH from those without. For example, there is no widely accepted single cut-off point for an abnormal pulmonary artery systolic pressure on TTE. Moreover, there are several limitations of TTE in its estimation of pulmonary artery pressures [1, 10–13]. Although the DETECT algorithm has high sensitivity for the detection of PAH in SSc, it misses a significant proportion of those with WHO groups 2 and 3 PH, both of which are common in adults with SSc [14].

The submaximal heart and pulmonary evaluation (step test) is a non-invasive, submaximal stress test that may have the ability to identify PH in patients with SSc [15]. The portable testing unit contains a 14 cm high step that patients step up and down on for 3 min. During the test, breathing pattern, gas exchange, and heart rate and rhythm are monitored using a simplified gas exchange system (Shape Medical Systems, Inc., St Paul, MN, USA) that was designed for submaximal exercise testing [16]. The entire test lasts for 6 min: 2 min of resting baseline monitoring, 3 min of step exercise and 1 min of recovery. It is submaximal because subjects are not required to achieve maximal oxygen consumption () as they are in a traditional cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET)—a feasible task for patients with musculoskeletal or cardiopulmonary disease.

The step test measures end tidal carbon dioxide () and the ratio of minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production (). is the partial pressure of carbon dioxide measured at end exhalation [17]. It is positively correlated with cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow, and negatively correlated with pulmonary vascular resistance [15, 18]. Patients without PH can increase their cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow in response to exercise, leading to increased perfusion of alveoli, which thereby leads to an increase in [15, 19]. Patients with PH, however, cannot substantially augment their cardiac output or pulmonary blood flow in response to exercise, leading to ventilation/perfusion mismatch, which thereby leads to a decrease in [15, 19]. and are inversely correlated [15]. The higher the value for throughout exercise, the more inefficient is a patient’s breathing.

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether from rest to end-exercise, as measured by the step test, differs between SSc patients with and without PH. We hypothesized that SSc patients with PH would have a smaller than SSc patients without PH. A secondary aim of this study was to determine whether , as measured by the step test, differs between SSc patients with PH and those without. We hypothesized that SSc patients with PH would have a higher and therefore more inefficient breathing than SSc patients without PH. Additional secondary aims of this study were to determine whether scores on three validated patient self-report questionnaires [Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR), Borg Dyspnoea Index (BDI) and Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SHAQ)] correlate with , and whether they differ between SSc patients with and without PH. Exploratory aims included whether potential biomarkers of PH (VEGF, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), IL-6 and plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)] correlate with , and whether these biomarkers differ between SSc patients with and without PH.

Methods

Study design

In this cross-sectional study, patients with lcSSc or dcSSc were identified by ICD-9 code 710.1 from academic cardiology and rheumatology practices, and the diagnosis validated via chart review. Subjects were validated as SSc if they were diagnosed with SSc by a rheumatologist. Any validated lcSSc or dcSSc patient ⩾18 years who underwent an RHC within the previous 24 months was eligible to participate. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, unable to step for 3 min, or used continuous supplemental oxygen. The study consisted of one 90-min visit during which informed consent was obtained, a history and physical examination focused on SSc and PH performed, the step test administered and blood drawn for SSc-specific autoantibodies and potential PH biomarkers. Patients completed study questionnaires online via REDCap, a secure, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) compliant, web-based application designed to support data capture and management [20].

The primary outcome was , as measured by the step test, which was compared between patients with and without PH. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hospital for Special Surgery and Weill Cornell Medical College.

Patient reported outcomes

The SHAQ assesses physical function and health-related quality of life in SSc [21]. It combines the HAQ-Disability Index, a 20-item musculoskeletal-targeted index, with five visual analogue scales to measure the severity of RP, digital tip ulcerations, pulmonary symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms and overall disease severity from the patient’s perspective [22]. The CAMPHOR assesses health-related quality of life in patients with PH [23, 24]. The BDI assesses patients’ overall perception of breathlessness over the previous 24 h on a scale of 0–10, with 0 being nothing at all and 10 being maximal [25].

Biomarker assays

VEGF is an endothelial cell-specific mitogen that is upregulated during chronic exposure to hypoxia [26, 27]. HIF-1α is a nuclear factor that is induced by hypoxia, expression of which is tightly regulated by oxygen tension at the cellular level [28]. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine that can have pro-inflammatory effects. Increased circulating levels of IL-6 have been identified in SSc patients with PH [29]. NT-proBNP is a 76-amino-acid natriuretic peptide released primarily from the heart in the setting of increased wall stretch [30]; levels are often elevated in patients with PH.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR

HIF-1α and VEGF mRNAs were measured by extracting total cellular RNA from whole blood using the PAXgene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the concentration of RNA determined using the NanoDrop 2000C (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The RNAs (1 μg) were converted to cDNAs using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TaqMan reagents in the ABI HT7900 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A singleplex reaction mix was prepared using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The thermal cycling conditions included an initial incubation at 50 °C for 2 min, then 95 °C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min as described in the manufacturer’s protocol.

Determination of serum concentration of IL-6, VEGF and NT-proBNP

The serum concentrations of IL-6, VEGF and NT-proBNP were measured using quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay kits from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Biomedica (Vienna, Austria) following the manufacturers’ instructions. The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were, respectively, ⩽4.2 and ⩽6.4% for IL-6; ⩽6.7 and ⩽8.8% for VEGF; and ⩽8.0 and ⩽7.0% for NT-proBNP. The measurement ranges of the IL-6, VEGF and NT-proBNP assays were 1.56–300.0, 31.2–2000.0 and 200–6400 pmol/l, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Sixteen SSc patients with PH and eight without PH yield 80% power to detect a mean difference of 3 mmHg in between SSc patients with PH and those without. Statistical analysis was performed using Wilcoxon’s rank sum test, Fisher’s exact test, the chi-square test and Spearman’s correlation, as appropriate. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

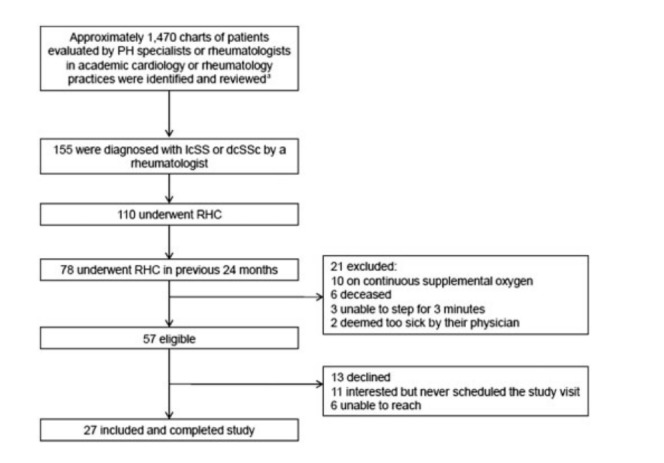

Charts of approximately 1470 patients who were evaluated by PH specialists in an academic cardiology practice or by rheumatologists in an academic rheumatology practice were identified and reviewed. Of these, 155 patients had received a diagnosis of lcSSc or dcSSc from a rheumatologist. Of these, 110 had undergone an RHC, 78 of whom had undergone an RHC within the previous 24 months. Fifty-seven of these patients were eligible for the study, all of whom were invited to participate, and 27 enrolled in and completed the study (Fig. 1). We have retrospectively applied the 2013 ACR/EULAR Classification Criteria for SSc to the patients in this study; all 27 patients (100%) fulfilled these criteria [31]. All study visits occurred between May 2012 and August 2013.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study participants

aThe majority of reviewed charts were of patients who did not have SSc evaluated by PH specialists. PH: pulmonary hypertension; RHC: right-sided heart catheterization.

The median (interquartile range (IQR)) age was 64.7 (52.9–70.4) years, 67% were female, 74% identified themselves as white, 70% had lcSSc and 67% had PH based on a previous RHC (Table 1). Of the 18 patients with PH, 89% had some component of WHO group 1 PH (or PAH), whether pure or mixed. Of the patients with serologies drawn as part of this study, 35% were ACA positive, 23% were anti-topo I (Scl-70) antibody positive and 4% were anti-RNA polymerase III positive (Table 1). Of the patients, 96% had a history of Raynaud’s and 89% had sclerodactyly (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology Online). Few patients were on immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications. However, many were on medications for PH (Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology Online).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variable | All patients (n = 27) | PH (n = 18) | No PH (n = 9) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 64.7 (52.9–70.4) | 61.9 (52.9–69.2) | 65.7 (56.4–70.3) | 0.64 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 18 (67) | 13 (72) | 5 (56) | 0.39 |

| White race, n (%) | 20 (74) | 13 (72) | 7 (78) | 0.76 |

| lcSSc, n (%) | 19 (70) | 13 (72) | 6 (67) | 0.77 |

| Disease duration, median (IQR), years | 16.4 (6.2–23.4) | 17.5 (6.4–26.1) | 11.5 (4.0–19.4) | 0.22 |

| Time between RHC and step test, median (IQR), days | 302 (160–536) | 302 (219–502) | 380 (141–684) | 0.64 |

| Pure WHO groupa 1 PH (pulmonary arterial hypertension), n (%) | 6 (33) | NA | ||

| Pure WHO group 2 PH (pulmonary venous hypertension), n (%) | 2 (11) | NA | ||

| Pure WHO group 3 PH (PH due to lung disease), n (%) | 0 (0) | NA | ||

| Mixed PH, WHO groups 1 and 2, n (%) | 1 (6) | NA | ||

| Mixed PH, WHO groups 1 and 3, n (%) | 6 (33) | NA | ||

| Mixed PH, WHO groups 1, 2 and 3, n (%) | 3 (17) | NA | ||

| Functional class, n (%) | 0.049 | |||

| I | 2 (7) | 1 (6) | 1 (11) | |

| II | 6 (22) | 3 (17) | 3 (33) | |

| III | 6 (22) | 2 (11) | 4 (44) | |

| IV | 13 (48) | 12 (67) | 1 (11) | |

| ACA positive, n (%) | 9/26 (35) | 6/17 (35) | 3/9 (33) | 0.92 |

| Anti-topo I (Scl-70) antibody positive, n (%) | 6/26 (23) | 2/17 (12) | 4/9 (44) | 0.06 |

| RNA polymerase III antibody positive, n (%) | 1/23 (4) | 1/16 (6) | 0/7 (0) | 0.99 |

| Results of studies, median (IQR) | ||||

| RHC mPAP, mmHg | 30 (21–41) | 35 (30–45) | 18 (16–21) | 0.0001 |

| RHC mean right atrial pressure, mmHg | 7.5 (4–9), n = 26 | 8 (5–9), n = 17 | 5 (2–7) | 0.07 |

| RHC pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mmHg | 11.5 (7–14), n = 26 | 13 (9–16), n = 17 | 10 (7–12) | 0.09 |

| RHC cardiac output, l/min | 4.5 (3.5–5.1), n = 20 | 4.3 (3.2–4.9), n = 14 | 5.0 (3.5–5.7), n = 6 | 0.28 |

| RHC pulmonary vascular resistance, Wood units | 4.0 (1.4–5.6), n = 22 | 5.1 (1.8–10.0), n = 16 | 1.7 (1.4–2.6), n = 6 | 0.10 |

| TTE PASP, mmHg | 49.5 (40.0–55.7), n = 25 | 54.8 (46.3–74.0), n = 16 | 40.0 (32.9–45.0) | 0.006 |

| PFT FVC, % predicted | 76.5 (66–84), n = 26 | 76 (68–96), n = 17 | 79 (66–84) | 0.75 |

| PFT DLCO, % predicted | 42.5 (34.5–55.0) | 41 (33–44), n = 13 | 63 (40–70), n = 7 | 0.057 |

| PFT FVC/DLCO | 1.84 (1.16–2.17), n = 20 | 2 (1.78–2.25), n = 13 | 1.09 (1.00–1.40), n = 7 | 0.01 |

| ILD on chest CT, n (%) | 15/22 (68) | 9/15 (60) | 6/7 (86) | 0.35 |

WHO group was determined by the patients’ treating physicians. DLCO: diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; FVC: forced vital capacity; mPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; PASP: pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PFT: pulmonary function test; PH: pulmonary hypertension; RHC: right heart catheterization; TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram.

Historical computed tomography scans of the lungs (chest CT) were available for 22 of the 27 patients in this study [median (IQR) time of 7.6 (4.1–13.9) months between chest CT and step test]. While 56% of the 27 participants reported a history of ILD (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology Online), 68% of the 22 who had chest CT reports available had radiographic evidence of ILD on chest CT (ground glass opacities, honeycomb cysts and/or fibrosis) (Table 1).

Ninety-three per cent of participants were able to complete the step test. Of the two non-completers, one stopped 15 s early and the other 20 s early, both due to fatigue. Per study protocol, 85% of participants were asked to increase their stepping rate if possible, due to a respiratory exchange ratio (which is measured continuously throughout the test but is checked at 1 min intervals during the duration of exercise) of <0.85. One hundred per cent of the participants were able to use the mouth piece.

SSc patients with PH had a statistically significantly lower median (IQR) than SSc patients without PH [−2.1 (−5.1 to 0.7) vs 1.2 (−0.7, 5.4) mmHg, P = 0.035], as well as a statistically significantly higher median (IQR) [53.4 (39–64.1) vs 36.4 (31.9–41.1), P = 0.035] (Table 2). In a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the 15 patients with evidence of ILD on chest CT, remained statistically significantly lower in the nine SSc patients with PH than in the six SSc patients without [−1.3 (IQR = −2.9 to 0.2) vs 0.35 (IQR = −0.7, 6.7) mmHg, P = 0.045]. and were moderately to strongly correlated with pulmonary artery systolic pressure on TTE and with diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide and the forced vital capacity/diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide ratio on pulmonary function testings (Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology Online).

Table 2.

Step test results

| Gas-exchange parameter | PH (n = 18) | No PH (n = 9) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| , mmHg | −2.1 (−5.1, 0.7) | 1.2 (−0.7, 5.4) | 0.035 |

| 53.4 (39–64.1) | 36.4 (31.9–41.1) | 0.035 |

Data presented as median (IQR). : change in end tidal carbon dioxide; PH: pulmonary hypertension; : minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production ratio.

Scores on the CAMPHOR symptom, functioning and quality of life scales were not statistically significantly different between SSc patients with and without PH (Table 3). In addition, scores on the energy, breathlessness and mood subscales of the CAMPHOR did not statistically significantly differ between SSc patients with and without PH (Table 3). Similarly, scores on the HAQ-DI component of the SHAQ, the RP, digital tip ulceration, pulmonary symptom, gastrointestinal symptom and overall disease severity visual analogue scales of the SHAQ, and the BDI did not statistically significantly differ between SSc patients with and without PH (Table 3). In addition, none of these self-reported outcome measures showed statistically significant correlations with on the step test (data not shown).

Table 3.

Patient self-report questionnaire scores

| Questionnaire | PH (n = 18) | No PH (n = 9) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAMPHOR | |||

| Symptom scale | 8 (4–12) | 6 (5–10) | 0.90 |

| Energy subscale | 4 (2–6) | 5 (2–6) | 0.68 |

| Breathlessness subscale | 3.5 (1–4) | 2 (2–4) | 0.56 |

| Mood subscale | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.72 |

| Functioning scale | 8.5 (6–15) | 7 (5–11) | 0.74 |

| Quality of life scale | 5 (2–8) | 5 (2–7) | 0.80 |

| SHAQ | |||

| HAQ-DI component | 0.88 (0.25–1.50) | 0.75 (0.13–1.25) | 0.74 |

| RP VAS | 15 (0–40) | 10 (2–35) | 0.91 |

| Digital tip ulceration VAS | 0.5 (0–8) | 1 (0–14) | 0.67 |

| Pulmonary symptom VAS | 39.5 (10–52) | 15 (11–50) | 0.94 |

| Gastrointestinal symptom VAS | 12.5 (0–50) | 12 (10–30) | 0.80 |

| Overall disease severity VAS | 50 (21–68) | 38 (27–56) | 0.88 |

| Borg Dyspnoea Index | 3 (1–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.99 |

Data presented as median (IQR). CAMPHOR: Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review; HAQ-DI: HAQ-Disability Index; PH: pulmonary hypertension; SHAQ: Scleroderma HAQ; VAS: visual analogue scale.

There were no statistically significant differences between SSc patients with and without PH in levels of IL-6 [4.46 (IQR = 3.72–10.54) vs 5.45 (IQR = 3.19–6.30) pg/ml, P = 0.77], VEGF [346.4 (IQR = 260.1–427.2) vs 265.2 (IQR = 228.9–468.2) pg/ml, P = 0.55], VEGF by qRT-PCR [27.86 (IQR = 27.46–28.29) vs 27.57 (IQR = 27.17–27.91), P = 0.47] or HIF-1α by qRT-PCR [23.62 (IQR = 22.98–23.80) vs 23.29 (IQR = 22.99–23.53), P = 0.40]. SSc patients with PH had higher NT-proBNP levels than those without [1152.19 (IQR = 503.72–2207.59) vs 566.61 (IQR = 296.22–902.32) fmol/ml, P = 0.08], although this was not a statistically significant difference. None of these laboratory-based secondary outcomes demonstrated statistically significant correlations with on the step test (data not shown).

Discussion

Our cross-sectional study demonstrated that on the step test was statistically significantly lower and was statistically significantly higher in SSc patients with PH than in SSc patients without PH. However, scores on the SHAQ, CAMPHOR and BDI were similar between both groups, as were levels of IL-6, VEGF and HIF-1α.

In a previous study of 40 patients with PH and 25 healthy controls, the step test was able to distinguish PH patients from healthy controls using and [15]. However, the majority of these patients did not have a systemic rheumatic disease, with only 8 of the 40 PH patients identified as having some type of unspecified connective tissue disease. Because patients with SSc may not necessarily have the same results from the step test as those with different aetiologies of PH, further studies were needed to evaluate whether the step test might perform as well in the SSc-PH population. Our group recently published a retrospective study of 19 SSc patients who had undergone both the step test and RHC, and found that from rest to end-exercise on the step test was statistically significantly correlated with mPAP as measured by RHC (r = −0.82, P = 0.0001) [32]. Moreover, on the step test had a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 75%, positive predictive value of 93.8% and negative predictive value of 100% for the diagnosis of PH, using RHC as the gold standard [32]. While these data were encouraging, most patients in our previous study were administered the step test as part of their routine clinical care, so that study was enriched for SSc patients being monitored for PH. To minimize confounding by indication, our cross-sectional study systematically enrolled any qualifying SSc patient with a recent RHC.

The step test was well tolerated by the SSc patients in this study. Even those with oral apertures as small as 4 cm were able to use the mouthpiece, which is more flexible than those used for traditional CPETs. All but two patients were able to complete the test (and those two stopped just a few seconds early), and there were no adverse events associated with its use.

There are some limitations of this study. First, the sample size was relatively small, and participants were recruited from academic practices; they may not, therefore, be representative of all SSc patients. Second, patients were included if they had undergone an RHC in the 24 months prior to screening (median time of 302 days between RHC and step test). Ideally, RHC and step test would have occurred within a shorter time period, as changes in therapy could have occurred in the period between RHC and step test, potentially affecting lung physiology. However, in our previous study, discordance in medication use between RHC and the step test did not affect the strength of association between on the step test and mPAP on RHC [32]. In addition, in our previous study, patients may have been preferentially administered the step test because they were not responsive to therapy, or because they were too ill for a repeat RHC. Therefore, our current study in which patients were administered the step test as part of an investigational protocol removes the bias by indication inherent in an observational retrospective study. Moreover, even though there was a long time (median of 368 days) between RHC and step test in our previous retrospective study, controlling for time between the two tests did not affect the strength of the association between and mPAP [32].

Because of the lag time between RHC and step test in this study, it is possible that some patients classified as no PH actually developed PH during the interval between RHC and step test, especially because 100% of patients in the study—including those in the no PH group—reported dyspnoea on exertion, and some patients in the no PH group were on vasodilators (calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists) for treatment of Raynaud’s. However, causes of dyspnoea on exertion are multifactorial, and all of the patients were followed regularly at expert PH care centres. Thus, progressive dyspnoea would have triggered repeat RHC for clinical reasons. However, none of the patients in this study required a repeat RHC during the interval between RHC and step test. Moreover, if some patients with PH were misclassified as no PH, our results would have been biased toward the null, making it less likely to find a statistically significant difference in between the two groups.

There are several strengths of this study. All participants were administered the step test in a controlled, reproducible research setting, and not because of a predetermined clinical concern. Our findings suggest that and might be useful in the routine evaluation of SSc patients for PH. Moreover, in a subgroup analysis limited to those SSc patients with chest CT evidence of ILD, remained statistically significantly different between SSc patients with and without PH. Although more work is needed, this suggests that the presence of ILD does not confound the results of the step test. This study lays the groundwork for future studies seeking to devise an algorithm for the screening of SSc patients for PH using and . A combination of and on the step test has also been used to determine severity of PAH [15], and could be assessed in future studies to establish whether it could determine the severity of SSc-associated PAH, although it is important to note that in this study we included patients with WHO groups 1, 2 and 3 PH and did not limit inclusion to those with PAH. We included a well-characterized group of SSc patients. All patients had been diagnosed with SSc by a rheumatologist, and detailed, systematic histories and focused physical examinations were performed as part of this study in order to gather robust clinical data. In addition, all but one patient whose vein could not be accessed had the three most common SSc-antibodies drawn as part of this study, and thus patients were well-characterized serologically.

Our study suggests a potentially important role for the use of the step test in clinical practice. This device is a relatively compact, portable unit that could be used in an office setting for the evaluation of SSc patients in real time. Physicians could therefore gather important physiological data during an office visit to help inform subsequent testing, and potentially treatment decisions as well (although RHC remains the gold standard for diagnosis of PH, and RHC results should determine whether to initiate a patient on PH-targeted therapy). Because the physiological information provided by the step test on patients’ breath-to-breath gas exchange is gathered at a submaximal exercise level, and patients are not required to achieve , this test could be administered to SSc patients with musculoskeletal or cardiopulmonary disease who are unable to perform a standard CPET.

Conclusion

This study is the first to show that gas-exchange parameters measured by the step test, a non-invasive, submaximal stress test, are statistically significantly different between SSc patients with and without PH. The step test appears to be a useful clinical tool for the evaluation of PH in patients with SSc. Larger prospective studies are needed to determine whether and correlate with changes in mPAP over time, and to develop a screening algorithm for PH in patients with SSc that incorporates and .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rosemarie Gadioma and Birgit Jorgensen for administering the step tests.

Funding: This study was funded by an Arthritis Foundation Clinical to Research Transition Award and grant KL2TR000458 from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology Online.

References

- 1. Bossone E, Duong-Wagner TH, Paciocco G. et al. Echocardiographic features of primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1999;12:655–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mukerjee D, St George D, Coleiro B. et al. Prevalence and outcome in systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: application of a registry approach. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hachulla E, Gressin V, Guillevin L. et al. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: a French nationwide prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:940–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sprung CL, Pozen RG, Rozanski JJ. et al. Advanced ventricular arrhythmias during bedside pulmonary artery catheterization. Am J Med 1982;72:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sprung CL, Elser B, Schein RM. et al. Risk of right bundle-branch block and complete heart block during pulmonary artery catheterization. Crit Care Med 1989;17:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abreu AR, Campos MA, Krieger BP. Pulmonary artery rupture induced by a pulmonary artery catheter: a case report and review of the literature. J Intensive Care Med 2004;19:291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoeper MM, Lee SH, Voswinckel R. et al. Complications of right heart catheterization procedures in patients with pulmonary hypertension in experienced centers. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:2546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ranu H, Smith K, Nimako K, Sheth A, Madden BP. A retrospective review to evaluate the safety of right heart catheterization via the internal jugular vein in the assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Clin Cardiol 2010;33:303–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murata I, Takenaka K, Yoshinoya S. et al. Clinical evaluation of pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis and related disorders. A Doppler echocardiographic study of 135 Japanese patients. Chest 1997;111:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brecker SJ, Gibbs JS, Fox KM, Yacoub MH, Gibson DG. Comparison of Doppler derived haemodynamic variables and simultaneous high fidelity pressure measurements in severe pulmonary hypertension. Br Heart J 1994;72:384–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fisher MR, Forfia PR, Chamera E. Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:615–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rich JD, Shah SJ, Swamy RS, Kamp A, Rich S. Inaccuracy of Doppler echocardiographic estimates of pulmonary artery pressures in patients with pulmonary hypertension: implications for clinical practice. Chest 2011;139:988–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coghlan JG, Denton CP, Grunig E. et al. Evidence-based detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: the DETECT study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1340–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woods PR, Frantz RP, Taylor BJ, Olson TP, Johnson BD. The usefulness of submaximal exercise gas exchange to define pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;30:1133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller AD, Woods PR, Olson TP. et al. Validation of a simplified, portable cardiopulmonary gas exchange system for submaximal exercise testing. Open Sports Med J 2010;4:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsumoto A, Itoh H, Eto Y. et al. End-tidal CO2 pressure decreases during exercise in cardiac patients: association with severity of heart failure and cardiac output reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yasunobu Y, Oudiz RJ, Sun XG, Hansen JE, Wasserman K. End-tidal PCO2 abnormality and exercise limitation in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2005;127:1637–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dumitrescu D, Oudiz RJ, Karpouzas G. et al. Developing pulmonary vasculopathy in systemic sclerosis, detected with non-invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing. PloS One 2010;5:e14293.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khanna D. Assessing disease activity and outcome in scleroderma In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology, 5th edn Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011:1367–71. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr. The value of the Health Assessment Questionnaire and special patient-generated scales to demonstrate change in systemic sclerosis patients over time. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1984–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKenna SP, Doughty N, Meads DM, Doward LC, Pepke-Zaba J. The Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR): a measure of health-related quality of life and quality of life for patients with pulmonary hypertension. Qual Life Res 2006;15:103–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gomberg-Maitland M, Thenappan T, Rizvi K. et al. United States validation of the Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR). J Heart Lung Transplant 2008;27:124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982;14:377–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med 2003;9:669–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Papaioannou AI, Zakynthinos E, Kostikas K. et al. Serum VEGF levels are related to the presence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis. BMC Pulm Med 2009;9:18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lemus-Varela ML, Flores-Soto ME, Cervantes-Munguia R. et al. Expression of HIF-1 alpha, VEGF and EPO in peripheral blood from patients with two cardiac abnormalities associated with hypoxia. Clin Biochem 2010;43:234–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pendergrass SA, Hayes E, Farina G. et al. Limited systemic sclerosis patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension show biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury. PloS One 2010;5:e12106.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leuchte HH, Holzapfel M, Baumgartner RA. et al. Clinical significance of brain natriuretic peptide in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:764–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J. et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernstein EJ, Mandl LA, Gordon JK, Spiera RF, Horn EM. Submaximal heart and pulmonary evaluation: a novel noninvasive test to identify pulmonary hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.