Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS:

Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, are at increased risk for colorectal cancer (CRC). Analyses of DNA methylation patterns in stool samples have been reported to detect CRC in patients with IBD. We sought to validate these findings in larger cohorts and assess the accuracy of analysis of DNA methylation patterns in stool for detection of CRC and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) normalized to methylation level at ZDHHC1.

METHODS:

We obtained buffered, frozen stool samples from a US case–control study and from 2 European surveillance cohorts (referral or population based) of patients with chronic ulcerative colitis (n = 248), Crohn’s disease (n = 82), indeterminate colitis (n = 2), or IBD with primary sclerosing cholangitis (n = 38). Stool samples were collected before bowel preparation for colonoscopy or at least 1 week after colonoscopy. Among the study samples, stools from individuals with IBD but without neoplasia were used as controls (n = 291). DNA was isolated from stool, exposed to bisulfite, and then assayed by multiplex quantitative allele-specific realtime target and signal amplification. We analyzed methylation levels of BMP3, NDRG4, VAV3, and SFMBT2 relative to the methylation level of ZDHHC1, and compared these between patients with CRC or HGD and controls.

RESULTS:

Levels of methylation at BMP3 and VAV3, relative to ZDHHC1 methylation, identified patients with CRC and HGD with an area under the curve value of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.77–1.00). Methylation levels at specific promotor regions of these genes identified 11 of the 12 patients with CRC and HGD, with 92% sensitivity (95% CI, 60%–100%) and 90% specificity (95% CI, 86%–93%). The proportion of false-positive results did not differ significantly among the case–control, referral cohort, and population cohort studies (P = .60) when the 90% specificity cut-off from the whole sample set was applied.

CONCLUSIONS:

In an analysis of stool samples from 3 independent studies of 332 patients with IBD, we associated levels of methylation at 2 genes (BMP3 and VAV3), relative to level of methylation at ZDHHC1, with detection of CRC and HGD. These methylation patterns identified patients with CRC and HGD with more than 90% specificity, and might be used in CRC surveillance.

Keywords: Complications, Neoplasm, Prevention, Noninvasive Test, Biomarker

Colorectal cancer (CRC) increases mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)1 because CRC risk is increased compared with the general population.2 Patients with ≥8 to 10 years of ulcerative colitis (UC) extending proximal to the rectum or Crohn’s disease (CD) involving one third or more of the colon are advised to undergo surveillance colonoscopy or chromoendoscopy at varying intervals determined by inflammatory activity, CRC family history, or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).3–5 Surveillance colonoscopy may downstage CRC,6 and may lower CRC-attributable mortality.7

Despite these benefits, compliance with this practice is suboptimal.8 Furthermore, approximately a third of CRC diagnosed in patients with chronic colitis are interval cancers.9 Thus, there is a critical need for a more patient-friendly yet highly accurate surveillance test for IBD patients.

To address these critical gaps, we and others have examined stool assay of DNA (sDNA) for the detection of colorectal neoplasia in patients with IBD.10,11 In a US referral center pilot study, aberrantly methylated DNA markers BMP3 and NDRG4 were 100% sensitive and 89% specific for CRC and high-grade dysplasia (HGD).10 These findings have not yet been replicated in larger patient cohorts or outside of America.

In addition, optimization of the sDNA marker panel is needed. The multitarget stool DNA test (MT-sDNA), as approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, is 93% to 100% sensitive for curable-stage CRC at 87% to 93% specificity.12,13 The MT-sDNA test uses a fecal immunochemical test for hemoglobin and quantitative allele-specific real-time target and signal amplification (QuARTS) to assay methylated BMP3 and NDRG4 as well as mutant KRAS and β-actin (ACTB). The latter, a marker of human DNA content, is used to normalize other DNA markers in a logistic regression algorithm. The Food and Drug Administration–approved MT-sDNA test may not be suitable for patients with IBD; occult or overt bleeding or leukocyte exudation from active inflammation in the colon may alter levels of hemoglobin and ACTB in stool.14 In addition, KRAS mutations are present in inflamed colonic epithelium or indolent hyperplastic polyps.15 In contrast, candidate methylated DNA markers BMP3 and NDRG4 appear less influenced by IBD activity and CRC risk factors.10,16

We hypothesized that an sDNA panel comprising well-selected methylated DNA markers would show high sensitivity for IBD-associated CRC+HGD and maintain high specificity across independent patient cohorts with varying baseline risk factors for colitis-associated neoplasia. We also hypothesized that discrimination would be improved when normalized by a novel methylated DNA marker for intestinal epithelium as an alternative to ACTB.

Methods

Study Overview

Markers were selected from a previously reported next-generation discovery experiment using next-generation sequencing.17 This data set was filtered by screening case–control tissue specimens followed by normal individual stool DNA to identify candidate markers for normalization of methylated DNA assays and candidate regions of differential methylation (DMR) between CRC and normal colon (Supplementary Methods section). Markers selected from these steps were brought forward to a clinical study of IBD patient stool samples. Novel epithelial markers used for normalization were screened in cell lines, blood samples, and stools, and also were included in the clinical study marker panel. Stool samples for the clinical study were obtained from 3 independent sources to measure sensitivity and specificity of the panel for CRC+HGD diagnosed in patients with known IBD and to assess disease covariates on panel accuracy. This end point was selected for the following reasons. First, if an alternative test to colonoscopy was offered to patients with poor compliance8 detection of CRC+HGD would be essential. Second, CRC+HGD events would be most critical to detect among highest-risk patients using a stool test in the interval between surveillance colonoscopies or in lower-risk patients in whom an interval stool DNA test could extend surveillance intervals.18 Third, cost effectiveness of sDNA relative to white light or chromocolonoscopy does not appear to be influenced by sensitivity for detection of low-grade dysplasia (LGD),19 LGD lesions 1 cm or larger in diameter are at increased risk of progression to cancer20 and therefore were included as a secondary end point. All stool samples were assayed as a single batch in blinded fashion.

Normalization Marker Selection

The reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) data set was investigated for methylated DNA segments that were highly methylated in both normal colon tissues and CRC tissues but with less than 2.5% methylation in buffy coat samples. To validate these candidates for suitability in normalizing a methylated DNA panel, we first measured each marker and ACTB in bisulfite-treated DNA from independent buffy coat and plasma samples as well as 2 CRC cell lines (HTC-116 and HT29; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA). We then measured each normalizing gene in pooled stool samples from sporadic CRC patients and normal patients using hybrid capture and QuARTS assays.

Clinical Study, Patients, and Populations

After institutional review board approval, subjects were recruited from 3 populations. The first included all patients with a pan–ulcerative colitis diagnosis for more than 8 years from Lovisenberg Diakonale hospital in Oslo, Norway, registered in a surveillance cohort since December 31, 2009. Each patient underwent chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies. The second included patients in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study of South-Eastern Norway (IBSEN) cohort, which includes all UC and CD patients (n = 843) diagnosed in the country of Norway between 1990 and 1994,21 due for a 20-year follow-up evaluation. Surveillance was performed with chromoendoscopy if available and standard-definition whitelight colonoscopy if not. The third population included cases and controls recruited from the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Cases were referred for evaluation of colorectal neoplasia arising in the setting of IBD and controls were enrolled from a cohort of IBD patients with negative surveillance colonoscopy using either chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies, high-definition white-light colonoscopy with random biopsies, or both. Stool samples were collected before bowel preparation for a diagnostic colonoscopy or at least 1 week after colonoscopy. Clinical metrics including IBD type, duration, disease extent, co-existing PSC, smoking history, and family history were collected for each enrolled subject to screen for associations with stool markers.

Patients were excluded if they had ileal CD only, resection of more than 50% of the colon, documented treatment of colorectal neoplasia before stool collection, incomplete or missing surveillance colonoscopy, or poor bowel preparation. To exclude effects from endoscopic therapy, patients with neoplastic findings were excluded if colonoscopy was performed before stool collection.

Please refer to the Supplementary Methods section for additional details on sample collection and processing, DNA capture from stool, bisulfite treatment, and QuARTS assays.

Statistical Analysis

For the marker discovery and selection studies, statistical analysis methods are reported in the Supplementary Methods section.

For the clinical study, sensitivity and specificity were estimated using a nominal logistic fit, performed on the logarithmic values of the marker strand counts with CRC+HGD as the event and dysplasia-free controls as the reference group. Once the model parameters were estimated, the fit score was applied to all subjects. This analysis was normalized with either bisulfite-treated β-actin or a novel methylated marker. A positive score was called at the 90th percentile value in nondysplastic controls. The secondary end point of CRC+HGD+LGD of 1 cm or greater also was examined.

With 12 cases and 325 controls, there was more than 95% power to detect an estimated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.8 or higher relative to a null area under the curve (AUC) of 0.5 using a 1-sided test of significance of 0.05. In addition, with 325 controls, the boundary on the 95% CI for specificity was no larger than ±5%. Estimates were reported with 95% CIs. The method of DeLong et al22 was used to estimate the 95% CIs of the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve.

Spearman correlation or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to assess the relationship of the logistic fit score with known risk factors for colitis-associated neoplasia, specifically, the duration of IBD, the presence or absence of PSC, disease activity (inactive, mild, or moderate/severe), and disease extent (left-sided vs extensive for UC patients). The predictive value of the logistic fit score was anticipated to vary among the different groups owing to differences in baseline risk factors and the prevalence of neoplastic end point le-sions, therefore specificity estimates were compared across each enrollment site.

Results

The discovery of differentially methylated regions and marker selection data are presented in the Supplementary Results section and in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Identification and Selection of Normalizing Markers

From the sequencing data, 3 candidate normalizing markers, each zinc finger encoding genes, ZDHHC1, ZMYM4, and ZFAND3 were identified. Table 1 shows strand counts of QuARTS assay products from 2 independent buffy coat samples, 2 independent plasma samples, and 2 colon cancer cell lines (HTC-116 and HT29), tested in duplicate to measure levels of NDRG4, BMP3, ACTB, ZDHHC1, ZFAND3, and ZMYM4. Markers ZFAND3 and ZMYM4 were deemed unsuitable as normalizing genes because they were moderately abundant in buffy coat. However, ZDHHC1 was most specific to epithelial cells and was undetectable in both inflammatory cells (buffy coat) and plasma. Furthermore, there was essentially no difference in ZDHHC1 levels in stools from patients with or without neoplasia (Supplementary Table 3). As a result, ZDHHC1 was selected as the normalizing gene for comparison with the standard ACTB for stool assays in the clinical study.

Table 1.

Strand Counts of Candidate Normalizing Markers Measured in Buffy Coat, Blood Plasma, and Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines

| Strand count |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | NDRG4 | BMP3 | BTACT | ZDHHC1 | ZFAND3 | ZMYM4 |

| Buffy coat 1 | 0 | 5 | 17,700 | 0 | 39,696 | 42,406,300 |

| Buffy coat 2 | 0 | 11 | 18,620 | 0 | 42,576 | 43,404,049 |

| Plasma 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 9574 |

| Plasma 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 9190 |

| HT29 1 | 66,207 | 64,542 | 114,059 | 143,256 | 105,399 | 35,929,831 |

| HT29 2 | 65,808 | 64,914 | 115,381 | 139,947 | 107,047 | 36,282,791 |

| HTC116 1 | 77,401 | 60,942 | 109,293 | 201,542 | 115,217 | 34,787,946 |

| HTC116 2 | 73,386 | 58,924 | 120,596 | 312,608 | 110,529 | 35,278,606 |

BTACT, bisulfite-treated β-actin.

For the clinical study, QuARTS assays were run in triplex format, and the final markers selected for the clinical study were as follows: NDRG4 and BMP3 normalized by ACTB; NDRG4 and BMP3 normalized by ZDHHC1; VAV3 and SFMBT2_897 normalized by ACTB; and VAV3 and SFMBT2_897 normalized by ZDHHC1.

Clinical Study

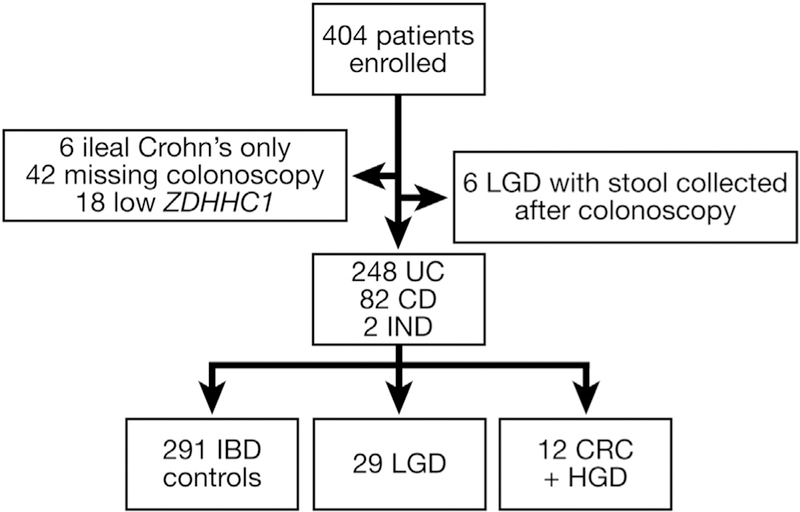

Across the 3 study populations, a total of 404 patients were enrolled. Six were excluded for having ileal CD only. In the surveillance cohorts, 42 patients had not completed their colonoscopy at the time of analysis. An additional 18 samples were excluded for insufficient amplification of ZDHHC1. Furthermore, 6 patients with LGD submitted their stool sample after surveillance colonoscopy. A total of 248 UC patients and 82 patients with CD and 2 patients with indeterminate colitis met all inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). The median time between stool collection and study colonoscopy was 1 day (interquartile range, 1–1 d) in the case–control group, 43 days (interquartile range, 14–92 d) in the Oslo cohort, and 52 days (interquartile range, 10–158 d) in the IBSEN cohort. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. The Mayo case–control population had a higher rate of PSC. The Oslo cohort was significantly younger and more likely to have UC. The disease duration was similar across groups. By design, the colorectal neoplasms were concentrated primarily in the case–control group. None of the control patients in the Mayo group and none of the patients in the Norwegian cohorts were known to have dysplasia before study entry. Of the Mayo case patients, a prior history of dysplasia was recorded in 1 of 5 CRC patients, in 1 of 5 HGD patients, and in 3 of 10 patients with LGD lesions of 1 cm or greater. Additional details on the end point neoplasms are provided in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Inflammatory bowel disease patients enrolled and included in the clinical study. IND, indeterminate colitis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Participating in the Stool Study

| Population |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site study subtype | Mayo referral case–control | Oslo referral cohort | IBSEN population-based cohort | P value |

| N | 154 | 57 | 121 | - |

| Men, n (%) | 80 (52) | 40 (70) | 68 (56) | .060 |

| Median age, y (IQR) | 59 (49–68) | 40 (33–56) | 54 (47–62) | <.0001 |

| Disease duration, y (IQR) | 17 (11–28) | 15 (9–21) | 20 (19–21) | .920 |

| UC, n (%) | 104 (68) | 57 (100) | 87 (72) | <.0001 |

| PSC, n (%) | 31 (20) | 4 (7) | 3 (2) | .003 |

| Extensive colitis, n (%) | 109 (77) | 56 (98) | 35 (29) | <.0001 |

| Neoplasmsa | CRC 5 | CRC 2 | CRC 0 | - |

| HGD 5 | HGD 0 | HGD 0 | - | |

| LGD 22 | LGD 4 | LGD 3 | - | |

IBSEN, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study of South-Eastern Norway; IQR, interquartile range; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC, ulcerative colitis.

The most advanced lesion within a patient counted.

Table 3.

Neoplasms Meeting Primary and Secondary End Points

| Lesion type | Stagea or size, cm | Lesion location | IBD diagnosis | IBD extent | PSC | Detected by stool DNAb | Neoplasia treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC | Stage | ||||||

| 1 | IIIC | Transverse | UC | Pan | No | Yes | Surgery |

| 2 | IIA | Sigmoid | UC | Pan | No | Yes | Surgery |

| 3 | I | Rectum | UC | Pan | No | Yes | Surgeryc |

| 4 | I | Ascending | UC | Pan | No | Yes | Surgery |

| 5 | I | Cecum | CD | Left | Yes | Yes | Surgeryc |

| 6 | IIIB | Descending | UC | Pan | Yes | Yes | Surgery |

| 7 | I | Transverse | UC | Pan | No | No | Surgeryc |

| HGD | Size | ||||||

| 1 | 6.2 | Cecum | CD | Right | No | Yes | Surgery |

| 2 | 2.5 | Transverse | UC | Pan | No | Yes | Endoscopicc |

| 3 | 1.3 | Sigmoid | UC | Left | No | Yes | Surgeryc |

| 4 | 1.5 | Descending | UC | Left | No | Yes | Surgery |

| 5 | 1.0 | Transverse | UC | Pan | Yes | Yes | Surgery |

| LGD >1 cm | |||||||

| 1 | 6.0 | Rectum | UC | Pan | No | Yes | Endoscopic |

| 2 | 5.0 | Rectum | UC | Pan | Yes | Yes | Endoscopic |

| 3 | 1.0 | Ascending | UC | Pan | No | No | Endoscopic |

| 4 | 1.5 | Ascending | CD | Right | No | No | Endoscopic |

| 5 | 7.1 | Descending | UC | Pan | No | No | Surgery |

| 6 | 1.1 | Ascending | UC | Pan | No | No | Endoscopic |

| 7 | 1.5 | Cecum | UC | Pan | No | No | Endoscopic |

| 8 | 2.0 | Descending | UC | Pan | Yes | No | Surgery |

| 9 | 2.5 | Rectum | CD | Pan | No | Yes | Endoscopic |

| 10 | 2.1 | Sigmoid | UC | Left | No | No | Endoscopic |

CD, Crohn’s disease; CRC, colorectal cancer; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; Pan, pancolonic; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual 8th edition.

At a 90% specificity cut-off threshold.

Neoplasms were upgraded from HGD to CRC or LGD to HGD, respectively, based on the post-therapy pathology specimen.

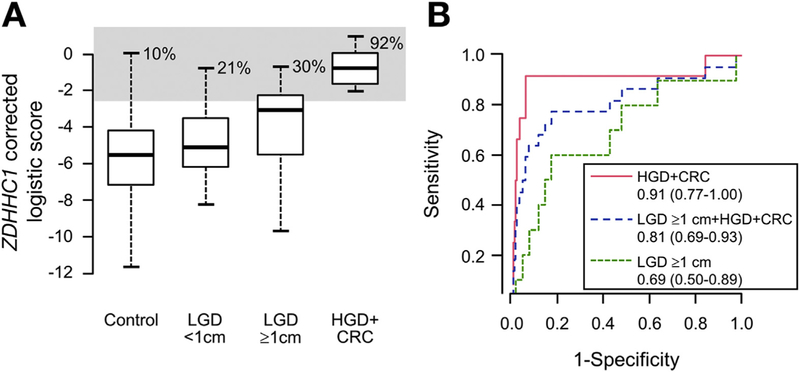

The logistic fit score based on the marker combination of BMP3, VAV3, and ZDHHC1 was less than −2.67 in 90% of controls. Positive calls for scores of −2.67 or greater were generated in 11 of 12 patients with CRC or HGD, for a sensitivity of 92% (95% CI, 60%–100%) at a specificity of 90% (95% CI, 86%–93%) (Figure 2A). Six (86%) of the 7 CRCs and 5 (100%) of the 5 HGDs were detected by the panel. The logistic score was used to generate an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.77–1.00) (Figure 2B) for the end point of CRC and HGD combined, compared with controls free from neoplasia.

Figure 2.

Detection of colorectal neoplasia by stool testing of methylated DNA marker panel. (A) Logistic fit score based on levels of methylated BMP3, VAV3, and ZDHHC1 for IBD patients with CRC or HGD in comparison with IBD patients free from neoplasia (controls). Logistic scores then were calculated for those with LGD with a diameter less than 1 cm or 1 cm or greater. Gray shaded area indicates scores greater than the 90th percentile for controls. (B) Areas under the receiver operating characteristics curves (95% CIs) for primary and secondary end points.

Of the 34 LGD lesions, just 10 (29%) were at least a centimeter in maximal diameter. When LGD of 1 cm or greater were included as target lesions, the panel detected 14 of 22 (64%; 95% CI, 41%–82%) of all so-called advanced neoplasms (CRC+HGD+LGD ≥1 cm) while maintaining a specificity of 90% (95% CI, 86%–93%). LGD lesions detected at 90% specificity were more likely to be rectal (3 of 3) than not (0 of 7) (P = .008) (Table 3). The AUC curves for each end point are shown in Figure 2B.

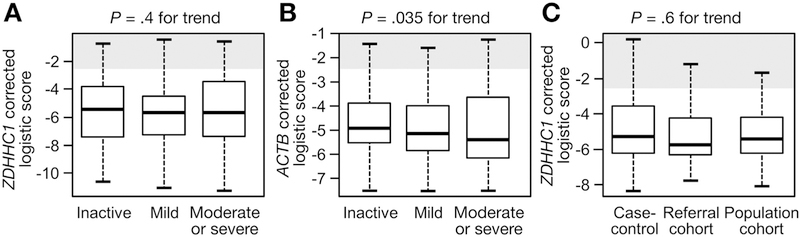

Despite differences in baseline CRC risk predictors, the median specificity of the ZDHHC1-corrected panel was similar across the spectrum of endoscopic disease activity (P = .34) (Figure 3A). In contrast, median specificities derived from the ACTB-corrected model scores were influenced significantly by endoscopic disease activity and were not considered further (P = .035) (Figure 3B). Specificity was not significantly different across each of the study populations with the ZDHHC1-corrected model (P = .6) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

For controls, scores for (A) the combination of methylated BMP3, VAV3, and ZDHHC1 were not impacted significantly by endoscopic IBD activity. (B) ACTB-corrected logistic fit was impacted significantly. (C) Study subtype did not significantly influence the logistic fit scores from BMP3, VAV3, and ZDHHC1.

The ZDHHC1-corrected logistic fit score was slightly less specific for men as well as those with extensive disease and those with PSC. There were no significant specificity differences attributable to patient age or IBD duration (Supplementary Figures 1–5).

Discussion

Next-generation sequencing techniques identified novel methylated DNA markers with high sensitivity and specificity for CRC. These novel markers show feasibility for the clinical detection of CRC+HGD in geographically diverse patients with IBD. The panel maintained excellent specificity for colitis-associated neoplasms despite anticipated differences in CRC risk among the patient groups.

Sequencing data additionally were mined to identify a novel epithelial-specific marker: methylated ZDHHC1. Found in both colorectal neoplasms and normal colorectal mucosae, ZDHHC1 appears to be a reliable measure of colon-specific DNA background in stool samples. Importantly, ZDHHC1-corrected markers were less affected by inflammatory activity than those corrected by ACTB, a marker of total human DNA.

These findings build on earlier observations of clinical feasibility of stool DNA assay for the detection of colitis-associated colorectal neoplasia.10,16 Those results were reported for raw marker strand counts because of the lack of certainty about the influence of IBD on levels of ACTB. The significantly larger IBD control sample size and the diversity of patients included in the present study improve confidence in the estimate of panel specificity for IBD-associated CRC+HGD.

The specificity estimates from this study are within the range of values required for effectiveness in a surveillance application, as shown in a recent Markov model.19 Compared with chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies and white-light colonoscopy with random biopsies, annual or every-other-year sDNA testing was the most cost-effective option. In sensitivity analyses, sDNA would not be the best option if specificity was less than 65%. The present data suggest that at a specificity threshold of 80%, sensitivity for LGD of 1 cm or greater would increase to 60% (Figure 2B).

In the IBD population, sDNA-based surveillance ideally would be applied at annual intervals to optimize the detection of endoscopically treatable precursors and surgically curable CRC. Such an approach also may help to lessen the observed 30% rate of interval CRCs in IBD patients undergoing surveillance colonoscopies.9 Although a hybrid surveillance approach with sDNA testing between colonoscopies has not yet been modeled, this strategy might be clinically useful for patients at particularly high risk.

This study had several limitations. The majority of CRC+HGD were prevalent (referred) events; only 2 CRCs were incident, detected by surveillance after stool collection. Although the CRC risk is 2- to 3-fold higher in patients with IBD compared with the general population,2 the low absolute number of incident events makes a prospective cohort design logistically formidable. For context, the most compelling evidence supporting surveillance in IBD patients has been generated by multidecade retrospective cohort or case–control designs, conducted at referral centers.6,7,23 The low number of events also limits the precision with which sDNA sensitivity can be estimated. However, the event rate of LGD in the IBSEN cohort was within expected population-level incidence rates of LGD among IBD patients from Olmsted County, MN.24 There were differences in colonoscopic methods among the study sites, which may have introduced variability in neoplasia detection among the cohorts. Approximately 5% of samples could not be analyzed because of insufficient recovery of ZDHHC1; this may have been attributable to variation in sample handling and processing in multiple different research laboratories. For a clinical rather than research test, the reproducibility of specimen handling methods in clinically certified laboratories would be assessed as previously described.12

Tissue studies previously reported in abstract form showed that the selected methylated DNA markers are found in nearly all colitis-associated primary tumors.16 The false-negative rate of 1 per 13 among CRC and HGD appears comparable with the performance of stool DNA testing in sporadic CRC screening.12 A negative test result in a patient with CRC could be due to stochastic variation in the exfoliation of assay targets into stool and may be diminished by inclusion of other tumor markers, such as mutant KRAS, albeit at a potential cost in test specificity. Finally, the logistic fit score was derived to identify cases among controls at varying levels of risk. The marker panel and analysis algorithm derived in this study will be retested in a large North American multicenter IBD control population (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02503696) and validated in an independent case and control study (NCT01819766), now in progress. It is anticipated that the validation study also will enroll a larger number of patients with LGD lesions of 1 cm or larger in size, which should permit more rigorous estimates of sDNA performance for lesions likely to progress to HGD or CRC.

In summary, we confirm the feasibility of sDNA assays for the detection of CRC+HGD in patients with IBD. A novel panel consisting entirely of methylated DNA markers is highly specific for colitis-associated neoplasia across geographically diverse patient subsets and among those with varying risk. The marker panel has been optimized by the discovery and incorporation of methylated ZDHHC1, an epithelium-specific marker, as a normalizer for the neoplasm-specific markers, in stool. Further studies are needed to corroborate and extend our findings.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) that involve the colon have a 2–3 fold increase in risk for colorectal cancer (CRC). Assays for methylated DNA markers in stool samples could be cost-effective for surveillance of this population, but these assays have not been validated.

Findings

In samples collected from patients with IBD at 3 centers, the assay for methylated DNA markers identified patients with CRC or high-grade dysplasia with 92% sensitivity and 90% specificity, validating the accuracy of this test. These values did not change significantly with patient geography, age, severity of inflammatory, or duration of IBD.

Implications for patient care

These findings provide further support of the clinical feasibility of analyzing stool DNA samples for CRC surveillance in patients with IBD. Identification of new methylated DNA markers might improve the accuracy of stool DNA tests for prevention of sporadic CRC.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Maxine and Jack Zarrow Family Foundation of Tulsa Oklahoma and the Paul Calabresi Program in Clinical-Translational Research (National Cancer Institute CA90628) (J.B.K.); and additional partial support was provided by Edmond and Dana Gong and the Carol M. Gatton endowment for Digestive Diseases Research. Sample collection was also supported by the Inflammatory Bowel Disease in South-eastern Norway (IBSEN) study group. Quantitative allele-specific real-time target and signal amplification assays were performed by Exact Sciences (Madison WI).

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ACTB

β-actin

- AUC

area under the curve

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- DMR

differentially methylated region

- HGD

high-grade dysplasia

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IBSEN

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study of South-Eastern Norway

- LGD

low-grade dysplasia

- MT-sDNA

multitarget stool DNA test

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- QuARTS

quantitative allele-specific real-time target and signal amplification

- RRBS

reduced representation bisulfite sequencing

- sDNA

stool assay of DNA

- UC

ulcerative colitis

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

These authors disclose the following: John B. Kisiel, David A. Ahlquist, Tracy C. Yab, William R. Taylor, and Douglas W. Mahoney could receive potential future royalties because Mayo Clinic has licensed intellectual property to Exact Sciences (Madison, WI); and Hatim T. Allawi, Maria Giakoumopoulos, Graham P. Lidgard, and Tamara Sander are employees of Exact Sciences. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Presented in part in abstract form at Digestive Diseases Week, May 2016, San Diego, California.

References

- 1.Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Levin TR, et al. Incidence and mortality of colorectal adenocarcinoma in persons with inflammatory bowel disease from 1998 to 2010. Gastroenterology 2012; 143:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or adenomas London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG118. Accessed October 1, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA technical review on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010; 138:746–774, 774 e1–4; quiz e12–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:639–651 e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi CHR, Rutter MD, Askari A, et al. Forty-year analysis of colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: an updated overview. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110:1022–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Cai T, et al. Colonoscopy is associated with a reduced risk for colon cancer and mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:322–329.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velayos FS, Liu L, Lewis JD, et al. Prevalence of colorectal cancer surveillance for ulcerative colitis in an integrated health care delivery system. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:1511–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mooiweer E, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Ponsioen CY, et al. Incidence of interval colorectal cancer among inflammatory bowel disease patients undergoing regular colonoscopic surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1656–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisiel JB, Yab TC, Nazer Hussain FT, et al. Stool DNA testing for the detection of colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37:546–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azuara D, Rodriguez-Moranta F, de Oca J, et al. Novel methylation panel for the early detection of neoplasia in high-risk ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1287–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redwood DG, Asay ED, Blake ID, et al. Stool DNA testing for screening detection of colorectal neoplasia in Alaska native people. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inokuchi T, Kato J, Hiraoka S, et al. Fecal immunochemical test versus fecal calprotectin for prediction of mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016; 22:1078–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson DH, Taylor WR, Aboelsoud MM, et al. DNA methylation and mutation of small colonic neoplasms in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis: implications for surveillance. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:1559–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisiel JB, Taylor WR, Allawi H, et al. Su1340 detection of colorectal cancer and polyps in patients with inflammatory bowel disease by novel Methylated stool DNA markers. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S-440–S-441. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor WR, Kisiel JB, Yab TC, et al. 109 discovery of novel DNA methylation markers for the detection of colorectal neoplasia: selection by methylome-wide analysis. Gastroenterology 2014; 146:S-30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutter MD, Riddell RH. Colorectal dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a clinicopathologic perspective. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisiel JB, Konijeti GG, Piscitello AJ, et al. Stool DNA analysis is cost-effective for colorectal cancer surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14:1778–1787 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi CHR, Ignjatovic-Wilson A, Askari A, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: risk factors for developing high-grade dysplasia or colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1461–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Hoie O, et al. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:1430–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooiweer E, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Ponsioen CY, et al. Chromoendoscopy for surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease does not increase neoplasia detection compared with conventional colonoscopy with random biopsies: results from a large retrospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Velayos FS, et al. Incidence and prognosis of colorectal dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.