Abstract

Background

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) fruit has a unique sweet-sour taste and is rich in beneficial compounds such as xanthones. Mangosteen originally been used in various folk medicines to treat diarrhea, wounds, and fever. More recently, it had been used as a major component in health supplement products for weight loss and for promoting general health. This is perhaps due to its known medicinal benefits, including as anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation. Interestingly, publications related to mangosteen have surged in recent years, suggesting its popularity and usefulness in research laboratories. However, there are still no updated reviews (up to 2018) in this booming research area, particularly on its metabolite composition and medicinal benefits.

Method

In this review, we have covered recent articles within the years of 2016 to 2018 which focus on several aspects including the latest findings on the compound composition of mangosteen fruit as well as its medicinal usages.

Result

Mangosteen has been vastly used in medicinal areas including in anti-cancer, anti-microbial, and anti-diabetes treatments. Furthermore, we have also described the benefits of mangosteen extract in protecting various human organs such as liver, skin, joint, eye, neuron, bowel, and cardiovascular tissues against disorders and diseases.

Conclusion

All in all, this review describes the numerous manipulations of mangosteen extracted compounds in medicinal areas and highlights the current trend of its research. This will be important for future directed research and may allow researchers to tackle the next big challenge in mangosteen study: drug development and human applications.

Keywords: Manggis, Garcinia mangostana L., Natural product, Pharmaceutical, Medicine

Introduction

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) belongs to the Guttiferae (syn. Clusiaceae) family, typically grown in tropical South East Asian countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand. Mangosteen fruit has become one of the major agricultural produce from these countries due to its high commercial value in various parts of the world including China, Japan, European, and Middle Eastern countries as well as the United States of America (www.fao.org, accessed November 2018; Table S1) (Dardak et al., 2011). The exotic appearance and unique sweet-sour taste of this fruit further enhance its appeal as a premium fruit on the shelves of most developed countries.

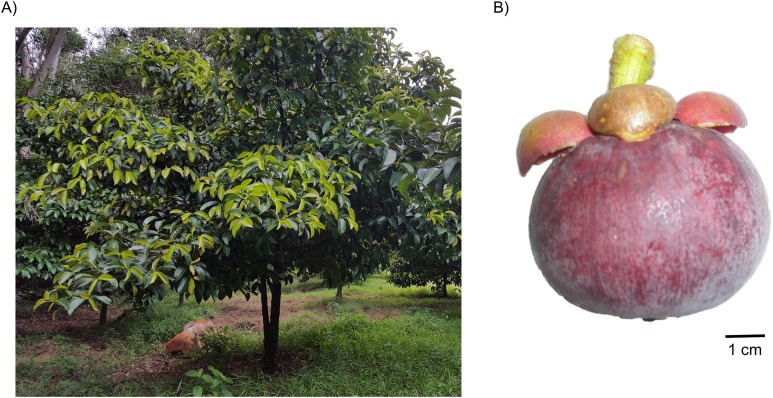

Mangosteen tree can reach up to six to 25 m height with lushes of leathery thick leaves canopying the tree (Fig. 1A) (Osman & Milan, 2006). Meanwhile its fruit is round with thick skin (or also called pericarp) and ripens seasonally, from green to yellow to pink spotted and finally full purple colored fruit (Fig. 1B) (Abdul-Rahman et al., 2017; Parijadi et al., 2018). The edible portion of the fruit resides within the pericarp, comprising of three to more than eight septa or also called aril, white in color and having sweet-sour taste (Osman & Milan, 2006). Its seeds also reside in one or two septa per fruit and are known to be recalcitrant, extremely sensitive to cold temperature and drying (Mazlan et al., 2018a, 2018b). The seeds of this fruit also develop apomictically without relying on sexual reproduction (Mazlan et al., 2019; Yapwattanaphun et al., 2014) as well as requiring a long period of planting before bearing (usually 7 to 9 years), which limits its agronomical improvement and cross-breeding (Osman & Milan, 2006). Furthermore, the top of the fruit is equipped with thick sepals which collectively resembles a crown, hence its popular designation, “The Queen of Tropical Fruit.” Such a designation is also commonly attributed to the plethora of medicinal benefits of this fruit as well as its unique taste (Fairchild, 1915).

Figure 1. A representative mangosteen tree grown at the experimental plot of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Malaysia (A) and a ripened mangosteen fruit (B).

Pictures are courtesy of Othman Mazlan, Institute of Systems Biology (INBIOSIS), UKM.

Mangosteen has been used in folk medicines such as in the treatment of diarrhea, wound infection, and fever (Osman & Milan, 2006; Ovalle-Magallanes, Eugenio-Pérez & Pedraza-Chaverri, 2017). Traditionally, various parts of mangosteen tree including leaves, root, and fruit are prepared by dissolving them in water or clear lime extract before usage (Osman & Milan, 2006). These days, mangosteen fruit extract is commonly commercialized as functional food or drink, with the addition of other minor components such as vitamins, which exhibits general health boost and even promoted as an anti-diabetic supplement (Udani et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2015). Furthermore, a plethora of studies have documented the fruit usages as anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and anti-hyperglycemic substance, perhaps due to containing bioactive compounds such as xanthones (El-Seedi et al., 2009, 2010; Ovalle-Magallanes, Eugenio-Pérez & Pedraza-Chaverri, 2017; Tousian Shandiz, Razavi & Hosseinzadeh, 2017). Interestingly, articles in this area has surged in recent years (Fig. S1) and hence, an updated review is timely to capture the current trends in mangosteen medicinal usages.

Survey methodology

Published manuscripts were obtained from various databases including Scopus, EBSCO, Web of Science, Pubmed, and Google Scholar by searching “mangosteen AND G. mangostana” in the search field. In this review, we critically cover recent articles (2016 and beyond) which is aimed to provide a comprehensive up-to-date research trend pertaining to mangosteen metabolites and their medicinal benefits.

Metabolite composition of mangosteen

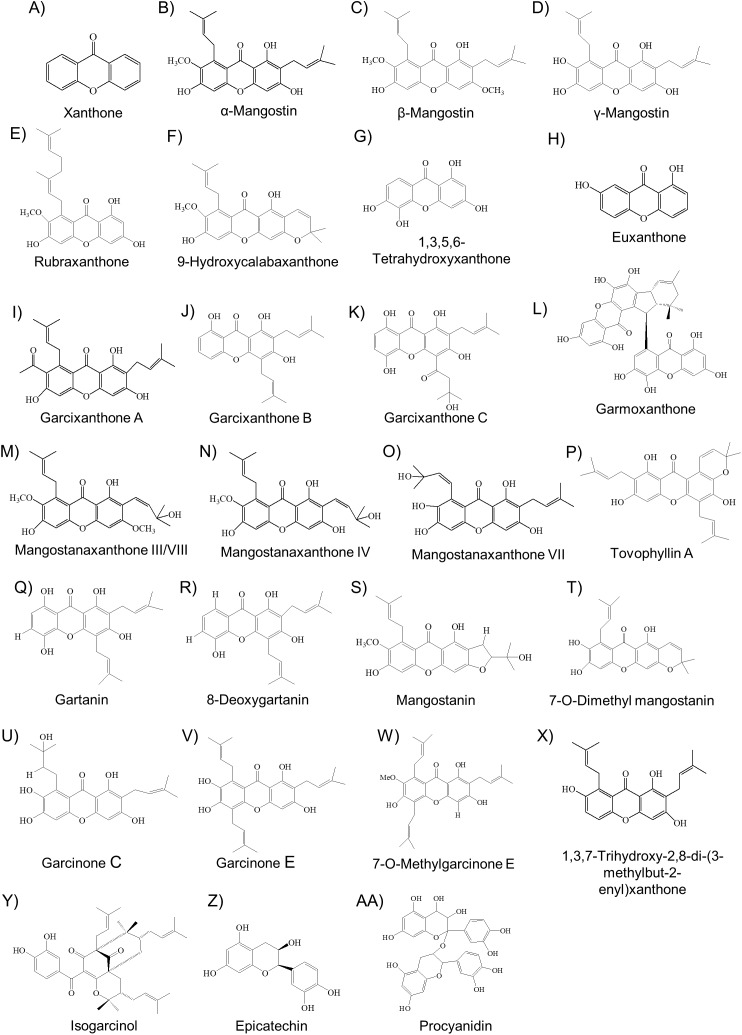

Xanthone is one of the compound classes that are prevalent in mangosteen (Tousian Shandiz, Razavi & Hosseinzadeh, 2017). These metabolites have been extracted and characterized in various studies as reviewed by several publications (Ovalle-Magallanes, Eugenio-Pérez & Pedraza-Chaverri, 2017; Tousian Shandiz, Razavi & Hosseinzadeh, 2017; Zhang et al., 2017b). So far, there are more than 68 xanthones isolated from the mangosteen fruit with the majority of them are α- and γ-mangostin (Ovalle-Magallanes, Eugenio-Pérez & Pedraza-Chaverri, 2017). The molecular structure of these compounds have been elucidated (Fig. 2) and readers are directed to Ovalle-Magallanes, Eugenio-Pérez & Pedraza-Chaverri (2017) for a more descriptive review and description on these xanthones. More recently, novel xanthones have been discovered such as 1,3,6-trihydroxy-2-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-8-(3-formyloxy-3-methylbutyl)–xanthone (Xu et al., 2016), 7-O-demethyl mangostin (Yang et al., 2017), garmoxanthone (Wang et al., 2018b) as well as mangostanaxanthone III, IV (Abdallah et al., 2017), V, VI (Mohamed et al., 2017), and VII (Ibrahim et al., 2018b) (Fig. 2). These xanthones were also implicated in various pharmaceutical properties but more studies are needed to verify their effectiveness in human applications.

Figure 2. The molecular structure of various bioactive compounds from mangosteen especially xanthones (A–X), benzophenone (isogarcinol) (Y), flavonoid (epicatechin) (Z), and procyanidin (AA).

Using High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Muchtaridi et al. (2017) measured the level of α-mangostin, γ-mangostin, and gartanin from different regions of Indonesia which suggest their levels can be dependent upon localities. This is interesting as xanthones may be extracted differently in different laboratories around the world, given that published manuscripts related to mangosteen and xantone extraction have originated from not just South East Asian countries, but also from United States, Japan, China, and United Kingdom (Fig. S2). Nevertheless, xanthones are known to be water insoluble and hence a few recent studies have attempted to extract such compounds by using non-polar solvents or other means possible. For instance, acetone and ethanol yielded the most amount of extracted xanthone and the highest antioxidant level compared to using other solvents such as ethyl acetate and hexane (Kusmayadi et al., 2018), whereas the extraction of α-mangostin using a single-solvent approach (methanol solvent) was more efficient compared to using an indirect solvent partitioning approach (methanol added with water then ethyl acetate extraction) as seen by the higher yield of the extracted compound (Sage et al., 2018). On the other hand, Machmudah et al. (2018) used subcritical water extraction to extract xanthones from mangosteen fruit, eliminating the need for the chemical solvents. Tan et al. (2017) and Ng et al. (2018) also showed that the aqueous micellar biphasic system they developed could also efficiently extract xanthones from mangosteen pericarp. This suggests that xanthones could be viable for human application but bioavailability studies need to be performed in the future to ascertain their delivery and efficacy. Interestingly, solubilizing α-mangostin in soybean oil (containing traces of linoleate, linolenic acid, palmitate, oleic acid, and stearate) improved the xanthone bioavailability in rats, such that the compound was found in brain, pancreas, and liver organs after 1 h treatment (Zhao et al., 2016). This signifies the potential of using oil-based formulation for increasing the bioavailability of xanthones.

While extracting and solubilizing natural xanthones have been the common strategies in mangosteen research all this while, a number of latest papers have reported the use of chemical modifications to alter the structure of xanthones. Buravlev et al. (2018) modified α-and γ-mangostin through Mannich reactions (aminomethylated at the C-4/C-5 positions) which consequently led to higher anti-oxidant activities than their original compounds. Furthermore, Karunakaran et al. (2018) showed that β-mangostin could inhibit the inflammatory response in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages, but this activity was not retained when the hydroxyl (OH) group at its position C-6 was replaced with acetyl or alkyl. These lines of evidence highlight the importance of certain functional groups in xanthones to confer their bioactivities including anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation.

Other than xanthones, mangosteen pericarp is also known to contain one of the highest procyanidin content, compared to other fruit such as cranberry, Fuji apple, jujube, and litchi (Zhang, Sun & Chen, 2017c). These procyanidins include monomer (47.7%), dimer (24.1%), and trimer (26%) may also contribute to the anti-oxidant capability of mangosteen extract as shown in 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) assays (Qin et al., 2017). Other phenolics such as benzoic acid derivatives (vanilic acid and protocatechuic acid), flavonoids (rutin, quercetin, cactechin, epicatechin) and anthocyanins (cyanidin 3-sophoroside) were also highly present in mangosteen pericarp (Azima, Noriham & Manshoor, 2017).

Furthermore, mangosteen compounds have also been profiled using metabolomics approach. Using GC-MS analysis, Mamat et al. (2018a) reported that mangosteen pericarp contains mainly sugars (nearly 50% of total metabolites) followed by traces of other metabolite classes such as sugar acids, alcohols, organic acids, and aromatic compounds. This study also found several phenolics such as benzoic acid, tyrosol, and protocatechuic acid which are known to possess anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities (Lin et al., 2009; Ortega-García & Peragón, 2010). Another GC-MS study by Parijadi et al. (2018) reported that sugars such as glucose and fructose as well as amino acids such phenylalanine and tyrosine were significantly increased during mangosteen ripening, suggesting active metabolic process during this process. Furthermore, the study also revealed the high abundance of secondary metabolites such as 2-aminoisobutyric acid and psicose at the end of ripening process, which are possibly implicated in prolonging the fruit shelf-life (Parijadi et al., 2018). LC-MS study has also been performed in mangosteen yet the full list of metabolites has not been released (Mamat et al., 2018b).

Medicinal usages of mangosteen

In this review, medicinal benefits of mangosteen are categorized into several distinct areas including anti-cancer, anti-microbes, and anti-diabetes (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, its protection against damages and disorders in various human organs such as liver, skin, joint, eye, neuron, bowel, and cardiovascular tissues, either in vitro (Table 1) or in vivo (Table 2) are also evaluated and discussed.

Table 1. Summary of mangosteen medicinal usages as performed in in vitro and in silico experimentation.

| Research types | Subject type | Compound name/extract used | Compound origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-cancer | ||||

| Oral cancer | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Fukuda et al. (2017) |

| Lung cancer | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Phan et al. (2018), Zhang, Yu & Shen (2017a) |

| Bile duct cancer | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | Aukkanimart et al. (2017) |

| Liver cancer | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Wudtiwai, Pitchakarn & Banjerdpongchai (2018) |

| Breast cancer | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Scolamiero et al. (2018) |

| Anti-multidrug resistance (breast, lung, and colon cancer) | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Wu et al. (2017) |

| Brain cancer | Cell lines | Gartanin | Fruit hull | Luo et al. (2017) |

| Ovary cancer | Cell lines | Garcinone E | Fruit pericarp | Xu et al. (2017) |

| Breast, lung and colon cancer | Cell lines | Garcixanthones B and C | Fruit pericarp | Ibrahim et al. (2018b) |

| Breast and lung cancer | Cell lines | Mangostanaxanthone VII | Fruit pericarp | Ibrahim et al. (2018d) |

| Breast and lung cancer | Cell lines | Garcixanthone A | Fruit pericarp | Ibrahim et al. (2018e) |

| Breast and lung cancer | Cell lines | Mangostanaxanthone VIII | Fruit pericarp | Ibrahim et al. (2018a) |

| Pancreatic cancer | Cell lines | α- and γ-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | Kim, Chin & Lee (2017) |

| Cervical cancer | Cell lines | α-Mangostin, gartanin | Fruit pericarp | Muchtaridi et al. (2018) |

| Hepatocellular, breast, and colorectal cancer | Cell lines | Mangostanaxanthone IV, garcinone E, α-mangostin (all lines) | Fruit hull | Mohamed et al. (2017) |

| Cervical, hepatoma, and gastric cancer | Cell lines | Garcinone E (all lines), 7-O-methylgarcinone E & α-mangostin (gastric) | Fruit pericarp | Ying et al. (2017) |

| Neuroendocrine, glioma, nasopharyngeal, lung, prostate and gastric cancer | Cell lines | 7-O-Demethyl mangostanin (all cancer lines), mangostanin, 8-deoxygartanin, gartanin, garcinone E, 1,3,7-trihydroxy-2,8-di-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)xanthone (neuroendocrine & glioma) | Fruit pericarp | Yang et al. (2017) |

| Breast cancer | Cell lines | Ethanol extract from pericarp | Soft part of fruit peel | Agrippina, Widiyanti & Yusuf (2017) |

| Lung cancer | Cell lines | Biofabrication water extracted mangosteen | Bark | Zhang & Xiao (2018) |

| Anti-microbes | ||||

| Oral bacteria | Microbial culture | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | Nittayananta et al. (2018) |

| Dental caries prevention | Microbial culture and human tooth | α-Mangostin | Fruit rind | Sodata et al. (2017) |

| Oral bacteria | Microbial culture | Ethanol: water extract | Fruit pericarp | Pribadi, Yonas & Saraswati (2017) |

| Oral and gastrointestinal bacteria | Microbial culture | Methanol extract | Fruit pericarp | Nanasombat et al. (2018) |

| Dental plaque | Microbial culture | Chloroform extract | Fruit pericarp | Janardhanan et al. (2017) |

| Anti-bacteria and anti-biofilm | Microbial culture | α-Mangostin | Fruit peel | Phuong et al. (2017) |

| Anti-bacteria and anti-biofilm | Microbial culture | α-Mangostin, ethanol extract | Fruit pericarp | Chusri et al. (2017) |

| Anti-bacteria | Microbial culture and cell lines | α-Mangostin inclusion complex | Fruit hull | Phunpee et al. (2018) |

| Anti-bacteria and anti-fungi | Microbial culture | α-Mangostin, 12 semi synthetic modified α-mangostin | Fruit hull | Narasimhan et al. (2017) |

| Anti-bacteria | Microbial culture | Garmoxanthone | Bark | Wang et al. (2018b) |

| Anti-bacterial and anti-fungal | Microbial culture | Ethyl acetate extract of leaf (lower activity in hexane and methanol extract) | Leaves | Lalitha et al. (2017) |

| Anti-bacteria | Microbial culture | N-hexane:ethyl acetate | Fruit pericarp | Sugita et al. (2017) |

| Anti-bacteria and anti-inflammation | Cell lines and human blood | Total extract using water and methanol | Fruit skin | Elisia et al. (2018) |

| Wound healing | Microbial culture | Not described | Not described | Panawes et al. (2017) |

| Anti-malaria | Microbial culture | Hexane, and ethylacetate fraction (weaker activity in water and butanol extract) | Fruit rind | Tjahjani (2017) |

| Anti-dengue virus | Cell culture | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Tarasuk et al. (2017) |

| Anti-diabetes | ||||

| Anti-diabetes, anti-cancer | Chicken liver | Garcinone E | Commercial | Liang et al. (2018) |

| Anti-diabetes | In vitro assay | Mangostanaxanthones III and IV, β-mangostin, garcinone E, rubraxanthone, α-mangostin, garcinone C, 9-hydroxycalabaxanthone | Fruit pericarp | Abdallah et al. (2017) |

| Anti-glycation | In vitro assay | Total extract using 95% ethanol | Fruit rind | Moe et al. (2018) |

| Anti-diabetes | In vitro assay | Total xanthone extract using hexane | Fruit pericarp | Mishra, Kumar & Anal (2016) |

| Anti-hypercholesterolemia | In silico | Epicatechin, euxanthone, and 1,3,5,6-tetrahydroxy-xanthone | Not relevant | Varghese et al. (2017) |

| Liver protection | ||||

| Hepatoprotective | Cell lines | γ-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | Wang et al. (2018a) |

| Anti-oxidant | Cell lines | Isogarcinol | Bark | Liu et al. (2018) |

| Skin protection | ||||

| Skin whitening | Cell lines | β-mangostin | Seedcases | Lee et al. (2017) |

| Anti-oxidant (skin) | In vitro assays | Dichloromethane extract | Fruit pericarp | Chatatikun & Chiabchalard (2017) |

| Photoprotective agent | Cell culture | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | Im et al. (2017) |

| Joint protection | ||||

| Anti-Osteoarthritis | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Pan et al. (2017a) |

| Anti-arthritis | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Zuo et al. (2018) |

| Eye protection | ||||

| Anti-retinal apoptosis | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Fang et al. (2016) |

| Neuronal protection | ||||

| Enzyme inhibitor for acid sphingomyelinase, important in lung diseases, metabolic disorders, and central nervous system disease | Cell lines | α-Mangostin and modified derivatives | Fruit pericarp | Yang et al. (2018) |

| Neuroprotective | Cell lines | γ-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | Jaisin et al. (2018) |

| Cardiovascular protection | ||||

| Anti-oxidant and anti-apoptosis for cardiac hypoxic injury | Cell lines | α-Mangostin | Commercial | Fang, Luo & Luo (2018) |

| Anti-oxidant | Cell lines | Procyanidins | Fruit pericarp | Qin et al. (2017) |

| Anti-oxidant | Cell lines | α- and γ-Mangostin and their derivatives | Dried yellow gum from fruit | Buravlev et al. (2018) |

| Anti-fertility | ||||

| Pro-spermatogenic apoptosis | Cell lines and cat organs | α-Mangostin loaded into nano-carrier | Fruit pericarp | Yostawonkul et al. (2017) |

Note:

Compound origin describes the mangosteen tissue used for extraction. Compounds obtained commercially without reference to any mangosteen tissue is denoted as “commercial.” “Not described” means that the corresponding manuscript did not disclose the compound or extract used in the reported study.

Table 2. Summary of mangosteen medicinal usages as performed in in vivo experimentation.

| Research types | Subject type | Compound name/extract used | Compound origin | Dosage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-cancer | |||||

| Skin cancer | Female mice | α-Mangostin | Commercial | 5 and 20 mg/kg BW | Wang et al. (2017) |

| Bile duct cancer | Hamster | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | 100 mg/kg BW | Aukkanimart et al. (2017) |

| Liver cancer | Rats | Extract powder | Fruit pericarp | 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg BW | Priya, Jainu & Mohan (2018) |

| Anti-microbes | |||||

| Anti-periodontitis | Human patient | Gel extract | Fruit rind | Not available | Hendiani et al. (2017) |

| Anti-periodontitis | Human patient | Gel extract | Fruit pericarp | 10 μL of 4% w/v | Mahendra et al. (2017) |

| Dental inflammation | Guinea pigs | Not described | Fruit peel | Not available | Kresnoadi et al. (2017) |

| Gingival inflammation | Rats | Not described | Fruit peel | 12.5% and 25.0% w/v | Putri, Darsono & Mandalas (2017) |

| Anti-diabetes | |||||

| Anti-diabetes, anti- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), anti-hepatosteatosis | Male rats | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | 25 mg/day | Tsai et al. (2016) |

| Anti-diabetes, renoprotective | Male mice | Xanthone | Commercial | 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg BW | Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong (2016) |

| Anti-glycemia and anti-hepatotoxic | Male mice | Mangosteen vinegar rind (MVR) contains 69.01% alpha mangosteen, 17.85% gamma mangosteen, 4.13% gartanin, 2.95% 8-deoxygartanin, 2.84% garcinone E, and 3.22% other xanthones | Fruit rind | 100 and 200 mg/kg BW | Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong (2018) |

| Anti-diabetes | Human respondents | Raw/tea | Fruit rind | Two to three times/day | Mina & Mina (2017) |

| Anti-hypercholesterolemia | Male rats | Not described | Fruit rind | 50, 150, 250, and 350 mg/kg BW. | As’ari & Asnani (2017) |

| Liver protection | |||||

| Hepatoprotective | Male mice | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | 12.5 and 25.0 mg/kg BW | Fu et al. (2018) |

| Hepatoprotective | Male mice | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | 100 and 200 mg/kg BW | Yan et al. (2018) |

| Hepatoprotective | Mice | γ-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | 5 and 10 mg/kg BW | Wang et al. (2018a) |

| Hepatoprotective, anti-inflammation | Male mice | Tovophyllin A | Fruit pericarp | 50 and 100 mg/kg BW | Ibrahim et al. (2018c) |

| Skin protection | |||||

| Anti-psoriasis (skin lesion) | Female mice | Isogarcinol | Fruit pericarp and bark | 100 mg/kg BW | Chen et al. (2017) |

| Photoprotective agent | Male mice | α-Mangostin | Fruit pericarp | 100 mg/kg BW | Im et al. (2017) |

| Joint protection | |||||

| Anti-Osteoarthritis | Male rats | α-Mangostin | Commercial | 10 mg/kg BW | Pan et al. (2017a) |

| Anti-inflammation, anti-arthritis | Male rats | α-Mangostin | Commercial | 10 mg/kg BW | Pan et al. (2017b) |

| Anti-arthritis | Male rats | α-Mangostin | Commercial | 40 mg/kg BW | Zuo et al. (2018) |

| Eye protection | |||||

| Anti-retinal apoptosis | Female mice | α-Mangostin | Commercial | 10 and 30 mg/kg BW | Fang et al. (2016) |

| Neuronal protection | |||||

| Anti-depressant | Male rats | Ethyl acetate extract | Fruit pericarp | 50, 150, and 200 mg/kg | Oberholzer et al. (2018) |

| Bowel protection | |||||

| Anti-colitis | Male mice | α-Mangostin | Not described | 30 and 100 mg/kg BW | You et al. (2017) |

| Anti-inflammatory (bowel) | Male mice | Ethanol extract | Fruit pericarp | 30 and 120mg/kg BW | Chae et al. (2017) |

| Cardiovascular protection | |||||

| Anti-hypertension, anti-cardiovascular remodeling | Male rats | Water extract | Fruit pericarp | 200 mg/kg BW | Boonprom et al. (2017) |

Notes:

Compound origin describes the mangosteen tissue used for extraction. Compounds obtained commercially without reference to any mangosteen tissue is denoted as “commercial.” “Not described” means that the corresponding manuscript did not disclose the compound or extract used in the reported study.

BW, body weight.

Anti-cancer

α-mangostin is the largest constituent of xanthone in mangosteen pericarp extract, and hence it is well researched and applied in various cancer cell lines (Table 1). This include gastric (Ying et al., 2017), cervical (Muchtaridi et al., 2018), colorectal, hepatocellular, and breast (Mohamed et al., 2017) cancer. Furthermore, α-mangostin at a concentration of 30 μg/mL was able to reduce multicellular tumor spheroids derived from breast cancer cell lines (Scolamiero et al., 2018). The viability of human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 cells as well as non-small cell lung cancer cells were also negatively affected when treated with 5 μM α-mangostin (Phan et al., 2018; Zhang, Yu & Shen, 2017a). Aukkanimart et al. (2017) further demonstrated that α-mangostin-induced apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer) cells and reduced such tumor in hamster allograft model. Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell lines at anoikis-resistance state (metastatic stage) was also sensitized with the treatment of α-mangostin (Wudtiwai, Pitchakarn & Banjerdpongchai, 2018). In addition, 20 mg/kg α-mangostin treatment reduced the rate of skin tumor incidence in mice (Wang et al., 2017). This suggests that α-mangostin has potent bioactivity against a diverse range of cancer cell lines and should be considered for drug developmental phase. Interestingly, α-mangostin can also inhibit ATP-binding cassette drug transporter activity, which implies that it is suitable for future cancer chemotherapy to overcome multi-drug resistance (Wu et al., 2017).

Another two bioactive xanthones from mangosteen are garcinone E and gartanin. Garcinone E has the ability to inhibit ovarian cancer cells and its action involved endoplasmic reticulum-induced stress through protective inositol-requiring kinase (IRE)-1α pathway (Xu et al., 2017). Both invasion and migration properties of the cancer cells were also significantly suppressed when treated with the compound, suggesting its potential use for anti-cancer drug (Xu et al., 2017). Furthermore, garcinone E also showed potential anti-cancer activity against cervical, hepatoma, gastric (Ying et al., 2017), breast, colorectal, and hepatocellular (Mohamed et al., 2017) cancer cell lines. Meanwhile, gartanin was demonstrated to inhibit HeLa cervical cancer cell lines (Muchtaridi et al., 2018) and suppressed primary brain tumor cells, glioma (Luo et al., 2017). The compound promoted the glioma cell cycle arrest via regulating phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian Target Of Rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway and induced anti-migration effect via mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathway (Luo et al., 2017). Besides gartanin and garcinone E, other known mangosteen compounds such as mangostanin, 8-deoxygartanin, and 1,3,7-trihydroxy-2,8-di-(3-methylbut-2-enyl) xanthone also showed considerable anti-cancer activity against neuroendocrine and glioma cancer cell lines (Yang et al., 2017). This again suggests the applicability of isolated compounds from mangosteen for the use in anti-cancer treatment.

Recently, several newly isolated xanthones from mangosteen pericarp were shown to possess anti-cancer properties (Table 1). For example, mangostanaxanthone IV has anti-cancer activity against human breast, hepatocellular, and colorectal cell lines (Mohamed et al., 2017). Other studies showed that mangostanaxanthone VII, mangostanaxanthone VIII, garcixanthone A, B, and C were able to exert anti-proliferative activity against breast and lung cancer cell lines (Ibrahim et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2018d, 2018e). Moreover, an investigation by Yang et al. (2017) revealed that a novel isolated xanthone called 7-O-demethyl mangostanin was effective against various cancer cell lines including neuroendocrine, glioma, nasopharyngeal, lung, prostate, and gastric cancer. These lines of evidence highlight that mangosteen still has more bioactive compounds to be discovered for medicinal application.

Total extracts of mangosteen which may contain various xanthones or other metabolites have also been shown to be effective against various cancer. For instance, total pericarp extract of mangosteen was able to protect rat liver from cancer-induced diethylnitrosamine (DEN) chemical (Priya, Jainu & Mohan, 2018). Agrippina, Widiyanti & Yusuf (2017) further observed that cellulose biofilm soaked with mangosteen pericarp extract was capable of killing T47D breast cancer cell lines. Furthermore, biofabricated silver nanoparticle containing water extract of mangosteen bark was reported to preferentially killed A549 lung cancer cells (Zhang & Xiao, 2018). In addition, Kim, Chin & Lee (2017) showed that the mixture of α- and γ-mangostin can inhibit pancreatic cancer cell lines. Their action were contributed by possible autophagy development via AMP-activated protein kinase/mTOR and p38 pathways (Kim, Chin & Lee, 2017). Interestingly, both compounds, together with a common drug called gemcitabine, were also found to synergistically inhibit the cancer cells (Kim, Chin & Lee, 2017), highlighting possible drug concoction for better treatment efficacy.

Anti-microbes

Extracted total xanthones from mangosteen has been shown to possess considerable anti-bacterial and anti-fungal activities (Table 1). Lalitha et al. (2017) showed that ethyl acetate extract of mangosteen leaf was able to inhibit the growth of various bacteria (Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus luteus, Enterobacter aerogenes, Escherichia coli, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Salmonella typhimurium) and fungi (Trichophyton mentagrophytes 66/01 and T. rubrum 57/01). Nanosized mangosteen pericarp extract has also been shown to possess anti-bacterial properties against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus and Shigella flexneri (Sugita et al., 2017). Furthermore, both water (1 mg/mL) and methanol (8.75 μg/mL) extracts of mangosteen pericarp were able to reduce interleukin-6 (IL-6) cytokine production in whole human blood assay infected with Escherichia coli (Elisia et al., 2018), suggesting that the extracts may not just kill bacteria but also act as an anti-inflammatory agent in humans. As such, mangosteen extract has also been used in products related to wound healing. For example, Panawes et al. (2017) demonstrated that gauze coated with both sodium alginate and mangosteen extract was able to inhibit gram positive bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 and ATCC 43300 as well as Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228.

Singly isolated compounds from mangosteen have also been implicated in anti-bacterial activity. For instance, Phuong et al. (2017) showed that α-mangostin acts as a bactericide to Staphylococcus aureus strains including one methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain which is known to be highly virulent and anti-biotic resistant. Moreover, the compound (α-mangostin) was able to inhibit the bacterial biofilm generation, in particular during its early stage formation. Similarly, various Staphylococcus spp. isolated from bovine mastitis were found susceptible to α-mangostin (minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) = 1–32 μg/mL) treatment (Chusri et al., 2017), suggesting wide inhibitory action of the compound toward staphylococci strains.

Interestingly, α-mangostin also has been conjugated or modified to be more soluble and potent against bacteria/fungi. Phunpee et al. (2018) revealed that α-mangostin forming inclusion complex with quaternized β-CD grafted-chitosan was able to inhibit Streptococcus mutans ATCC 25177 and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 growth with MIC values of 6.4 and 25.6 mg/mL, respectively. The soluble inclusion complex also possessed higher anti-inflammatory response than free α-mangostin (Phunpee et al., 2018), suggesting solubility may be critical in determining the compound effectiveness. Furthermore, α-mangostin has also been synthetically modified to several analogs particularly at the functional phenolic and iso-prenyl hydroxy groups (Narasimhan et al., 2017). These analogs possessed higher anti-bacteria (against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and anti-fungi (against Candida albicans and Aspergillus niger) activities compared to the original α-mangostin. This highlights the potential use of mangosteen derived compounds in various human applications to curb pathogen infection.

For instance, mangosteen extracts have been commonly used to protect and promote dental health by eradicating oral pathogens. Pribadi, Yonas & Saraswati (2017) showed that the ethanol extract of mangosteen pericarp was able to inhibit the activity of the glucosyltransferase enzyme from Streptococcus mutans, which is important for dental caries progression. Chloroform extract of the same tissue was also shown to be effective against the growth of Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus sanguis and Streptococcus mutans, which are the common pathogens causing dental caries (Janardhanan et al., 2017). Combination of α-mangostin (five mg/mL) and lawsone methyl ether (2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone) (250 μg/mL) has been shown to be effective against oral pathogens such as Streptococcus mutans, Candida albicans, and Porphyromonas gingivalis (Nittayananta et al., 2018). Furthermore, mangosteen extract including α-mangostin has been used as an anti-bacterial component in an adhesive paste to prevent dental caries (Sodata et al., 2017) as well as in a topical gel to cure chronic periodontitis (Hendiani et al., 2017; Mahendra et al., 2017). Interestingly, mangosteen not only kills oral pathogens but also mediate anti-inflammatory response in dental complications. For instance, mangosteen extract has also been shown to reduce inflammation related to gingivitis in rats (Putri, Darsono & Mandalas, 2017). Kresnoadi et al. (2017) further showed that the total extract of mangosteen pericarp could reduce the inflammation of post-tooth extraction in guinea pigs (Cavia cobaya). This can be attributed by the extract ability to lower the protein expression of nuclear factor κβ (NfkB) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κβ ligand in the treated group (Kresnoadi et al., 2017). These lines of evidence emphasize the use of mangosteen extract in promoting oral hygiene.

Another human application of mangosteen extract is for promoting gastrointestinal health. The growth of probiotic bacteria such as Lactobacillus acidophilus has been shown to be promoted by methanol extract of mangosteen pericarp (Nanasombat et al., 2018). Interestingly, the chloroform extract inhibited the bacteria growth (Janardhanan et al., 2017), suggesting the differences in compounds extracted between more polar (methanol) and lesser polar (chloroform) solvents. However, these studies did not further elucidate the exact compounds from their extracts.

Additionally, compounds from mangosteen may not only restrict bacterial and fungal growth, but also viral infection. For example, α-mangostin has been shown to inhibit dengue virus including all four serotypes (DENV1-4) in infected HepG2 cell lines (Tarasuk et al., 2017). Furthermore, the expression of several chemokine (Regulated upon Activation Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted (RANTES), Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1β (MIP-1β) and Interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10)) and cytokine (IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α)) genes were significantly suppressed in those infected cell lines when treated with α-mangostin (Tarasuk et al., 2017), suggesting that the compound may also mediate inflammatory response upon infection. Meanwhile, malarial parasites, Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 was also inhibited by hexane and ethyl acetate fractions of mangosteen (Tjahjani, 2017), further strengthening the anti-pathogenic use of this plant.

Anti-diabetes

Mangosteen plant extract is known to possess anti-diabetic properties. A nationwide survey in Philippines suggests that the use of mangosteen as tea (pericarp) or eaten raw (aril) could potentially curb diabetes amongst the local population (Mina & Mina, 2017). Although a more thorough clinical trials on human should be conducted, a plethora of recent research in vitro (Table 1) and in vivo (Table 2) have shown that mangosteen extract prospective use for anti-diabetic medication.

For example, various xanthones from mangosteen have been examined with inhibitory activity against certain enzymes or biochemical processes related to obesity. For instance, garcinone E demonstrated strong inhibitory activity against fatty acid synthase enzyme, which is highly expressed in both obese human adipocytes and cancerous cells (Liang et al., 2018). Moreover, two newly discovered xanthones from mangosteen called mangostanaxanthones III and IV prevented advanced glycation end-product, a process where proteins are added with sugars commonly occurring in diabetic cases (Abdallah et al., 2017). Total mangosteen extract has also shown promising result by inhibiting the glycation process in vitro (Moe et al., 2018) as well reducing the activity of digestive enzymes such as α-amylase and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (Mishra, Kumar & Anal, 2016). Furthermore, using an in silico approach, several mangosteen compounds such as 1,3,5,6-tetrahydroxyxanthone, euxanthone, and epicatechin were discovered to be lead compounds for inhibiting pancreatic cholesterol esterase, an important enzyme for hypercholesterolemia, a common syndrome associated with diabetes (Varghese et al., 2017). These highlight potentially specific anti-diabetic drugs from mangosteen could be further developed in the future.

Several in vivo studies to measure mangosteen effectiveness in ameliorating diabetes have also been conducted (Table 2). For instance, diabetic mice supplied with mangosteen vinegar rind (MVR) containing 69% α-mangostin for 1 week were showing relatively lower plasma glucose, total cholesterol, and low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels compared to non-treated diabetic control (Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong, 2018). Similarly, As’ari & Asnani (2017) showed that mangosteen pericarp extract was able to reduce LDL level in hypercholesterolemia male rats. Furthermore, MVR treatment reduced the levels of hepatotoxic enzymes in the diabetic mice, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase protecting liver from further damage (Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong, 2018). Moreover, xanthone extract containing 84% α-mangostin prevented triglyceride accumulation in the liver of high fat diet rats, thus avoiding hepatosteatosis complications related to diabetes (Tsai et al., 2016). This hepatoprotective benefit may be resulted from the anti-oxidant capacity of such xanthone extract, as seen by the lower level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the treated primary hepatocyte, possibly via the activation of anti-oxidant enzymes including glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (Tsai et al., 2016). Furthermore, diabetic mice treated with pure xanthone also improved kidney function by reducing malondialdehyde level, an oxidative stress indicator to prevent kidney hypertrophy (enlargement) (Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong, 2016). These findings advocate that the mangosteen extracts are not only useful in treating hyperglycemia, but also promoting both liver and kidney health in diabetic patients by way of ameliorating cellular oxidative stress.

Various organ protection

Mangosteen fruit extract has been shown to possess high anti-oxidant level (Chatatikun & Chiabchalard, 2017) as well as anti-inflammatory potential (Fu et al., 2018), which can protect organs such as liver, skin, joint, eye, neuron, bowel, and cardiovascular tissues from damages and disorders.

Mangosteen compounds have been demonstrated to protect liver damage from drug toxification and oxidative stress. For example, acetaminophen (APAP) drug is known to metabolized to a harmful substance that can increase oxidative stress of patients if taken excessively (Fu et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018). However, xanthones have been shown to attenuate the toxicity and damage on the liver cells of mice by preventing NfkB and MAPK activation, thereby reducing the inflammation on the liver (Ibrahim et al., 2018c; Yan et al., 2018). For instance, α-mangostin prevented the increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, Interleukin-1β, and TNF-α after treatment with APAP and inhibited the increase of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression, which further protects the liver tissue (Fu et al., 2018). Furthermore, isogarcinol has been shown to possess anti-oxidant activity, without cytotoxic and genotoxic effects on HepG2 liver cells (Liu et al., 2018). The compound also protects those cells from oxidative damage by H2O2, perhaps by increasing anti-oxidant enzymes such as SOD and glutathione as well as reducing the level of active Caspase-3 important for apoptosis (Liu et al., 2018). Wang et al. (2018a) further showed that another major compound from mangosteen, γ-mangostin also exhibited hepatoprotective ability. The compound induced the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) which is known to regulate many anti-oxidative enzymes such as heme oxygenase-1 and SOD2. Additionally, γ-mangostin also increased the expression of silent mating type information regulation 2 homologs 1 (SIRT1) which is important for maintaining cellular oxidative stress, in particular reducing ROS production from mitochondrial activity. The action of γ-mangostin in regulating both NRF2 and SIRT1 has been shown in both human hepatocyte cell line L02 induced by oxidants (tert-butyl hydroperoxide) as well as in mice treated with carbon tetrachloride toxic drug (Wang et al., 2018a), suggesting the applicability of this compound in ameliorating liver toxification and oxidative damage.

α-mangostin has also been shown to prevent skin damage and wrinkling due to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation in hairless mice (Im et al., 2017). The compound acts by reducing matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression, which are the collagen degradation enzymes as well as ameliorating ROS production and inflammation in UVB damaged skin (Im et al., 2017). Furthermore, β-mangostin from mangosteen was able to reduce tyrosine and tyrosinase-related proteins 1 levels to induce depigmentation for skin whitening (Lee et al., 2017). Another mangosteen compound, isogarcinol was shown to be effective against psoriasis (skin lesion) in mice, possibly through mediating pro-inflammatory factors and cytokines (Chen et al., 2017). These suggest that compounds from mangosteen may target certain enzymes from melanogenesis, an important regulatory process for skin protection and complexion.

Mangosteen extract particularly α-mangostin has also been primarily investigated as an anti-arthritic substance. Arthritis is a chronic joint disorder mainly caused by inflammation. Pan et al. (2017a) showed that osteoarthritic rats treated with α-mangostin delayed their cartilage loss. This can be attributed to the compound ability to ameliorate apoptosis and inflammation responses in the cartilage chondrocyte cells as observed by the inhibition of NfkB expression and other IL-1β induced proteolytic enzymes such as MMP-13 and A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin type 1 motifs, member 5 (ADAMTs-5) (Pan et al., 2017a, 2017b). Both Collagen II and Aggrecan proteins were also preserved in α-mangostin treated chondrocytes-induced degradation (Pan et al., 2017a, 2017b). In rheumatoid arthritis, α-mangostin could reduce fibroblast-like synoviocytes which play significant role in joint deprivation (Zuo et al., 2018). This was again due to the action of α-mangostin against NfkB which reduced the inflammatory signals in the arthritic rats (Zuo et al., 2018).

Recently, mangosteen extract has also been shown to improve macular diseases. Treatment with α-mangostin was able to increase SOD and glutathione peroxidase activities to protect mice retina from oxidative damage as well as preserving the retinal photoreceptor against light damage through inhibition of caspase-3 activity (Fang et al., 2016). Interestingly, α-mangostin also was able to accumulate in the retina, suggesting that the compound could pass the blood-retinal barrier (Fang et al., 2016). This again signifies the applicability of mangosteen extract to be used effectively for human application.

Furthermore, γ-mangostin has also been shown to have some potential against neuronal diseases such as Parkinson. The pretreatment of γ-mangostin onto SH-SY5Y cells was able to reduce apoptotic signals such as p38 MAPK phosphorylation and caspase-3 activity from an inducer of Parkinson, 6-hydroxydopamine (Jaisin et al., 2018). The pretreatment also well-preserved the cell viability by reducing the oxidative damage (Jaisin et al., 2018). Similarly, mangosteen extract containing both a- and γ-mangostin can be potentially used for anti-depressant due to its anti-oxidant ability as depression often leads to redox imbalance. The treatment of 50 mg/kg mangosteen extract onto the model animal of depression, flinders sensitive line rats was able to improve cognitive ability and promote the repair process of hippocampal damage of the rats (Oberholzer et al., 2018). α-mangostin also has been modified such that it can inhibit acid sphingomyelinase effectively which is often associated with central nervous system damage and metabolic disorder (Yang et al., 2018). This modified α-mangostin contains C10 hydrophobic tail extension which confer the potency of the compound, is also implicated in anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic action against an in vitro NIH3T3 fibroblast cell line treatments (Yang et al., 2018).

Bowel disease including ulcerative colitis is also shown treatable by applying mangosteen extract. For example, ethanol extract of the fruit pericarp containing 25% α-mangostin was able to lower the level of inflammatory proteins such as NfkB of which resulted in the reduction of colitis disease score in mice (Chae et al., 2017). Another report further suggested that the α-mangostin was widely distributed and retained longer in the colon of the treated mice, further increasing its efficacy in the colitis treatment (You et al., 2017).

Another study showed that hypertensive rats with high blood pressure and cardiovascular problems induced by a chemical called Nω-Nitro-l-arginine methyl ester was attenuated by mangosteen extract (200 mg/kg) daily treatment (Boonprom et al., 2017). Such a treatment also reduced the expression of NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox expression responsible for ROS generation, iNOS as well as other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α (Boonprom et al., 2017). An in vitro study using hypoxic-induced H9C2 rat cardiomyoblast cells further confirms xanthone roles, in particular α-mangostin to ameliorate oxidative and apoptotic events in cardiac injury (Fang, Luo & Luo, 2018). Furthermore, procyanidin extracted from mangosteen was able to rescue H2O2-treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Qin et al., 2017) while xanthones could protect red blood cells from severe H2O2 stress (Buravlev et al., 2018). This suggests that mangosteen extracts may not only protect the structural endothelial cells but also the components of blood vessels (red blood cells).

Interestingly, while mangosteen may contain a plethora of medicinal benefits, one recent study showed that it may act as anti-fertility substance. α-mangostin loaded into nanostructured lipid carriers has been shown to induce spermatogenic cell death and apoptotic Caspases 3/7 activities in testicular tissues of castrated cats (Yostawonkul et al., 2017). Even so, the complex also prevented cellular inflammation through reduced nitric oxide and TNF-α production; such a strategy can be used as a chemical-based animal contraception (Yostawonkul et al., 2017).

Conclusion

This review has covered recent articles related to mangosteen research particularly its compound profile as well as medicinal benefits. Evidently, many mangosteen bioactivities and medicinal benefits are contributed by the presence of phenolic compounds such as xanthones and procyanidins. These compounds are particularly effective against oxidative damage and inflammatory response. As such, mangosteen compounds were able to inhibit cancer and bacterial growth as well as protecting various organs such as liver, skin, joint, eye, neuron, bowel, and cardiovascular tissues from disorders. Despite these benefits, mangosteen compounds have yet to be developed as prescription drugs and hence future effort in human applications should be emphasized.

Supplemental Information

Statistics were obtained from SCOPUS database on July 2018 by searching “mangosteen AND Garcinia mangostana” in the “Article title, Abstract and Keywords” search field. Please refer to Supplementary File 1 for the raw data.

Statistics were obtained from SCOPUS database on July 2018 by searching “mangosteen AND Garcinia mangostana” in the “Article title, Abstract and Keywords” search field.

Data obtained from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) accessed on November 2018 (www.fao.org).

Statistics were obtained from SCOPUS database on July 2018 by searching “mangosteen AND Garcinia mangostana” in the “Article title, Abstract and Keywords” search field.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) Research University Grant (GUP-2018-122), a Sciencefund grant (02-01-02-SF1237) from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI), and the Malaysia and Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/2/2014/SG05/UKM/02/2) from the Ministry of Education (MOE), Malaysia. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Wan Mohd Aizat conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Ili Nadhirah Jamil analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Faridda Hannim Ahmad-Hashim prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Normah Mohd Noor analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data is available in the Supplementary File.

References

- Abdallah et al. (2017).Abdallah HM, El-Bassossy HM, Mohamed GA, El-Halawany AM, Alshali KZ, Banjar ZM. Mangostanaxanthones III and IV: advanced glycation end-product inhibitors from the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana. Journal of Natural Medicines. 2017;71(1):216–226. doi: 10.1007/s11418-016-1051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Rahman et al. (2017).Abdul-Rahman A, Suleman NI, Zakaria WA, Goh HH, Noor NM, Aizat WM. RNA extractions of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) pericarps for sequencing. Sains Malaysiana. 2017;46(8):1231–1240. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2017-4608-08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agrippina, Widiyanti & Yusuf (2017).Agrippina WRG, Widiyanti P, Yusuf H. Synthesis and characterization of bacterial cellulose-Garcinia mangostana extract as anti breast cancer biofilm candidate. Journal of Biomimetics, Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering. 2017;30:76–85. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/jbbbe.30.76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- As’ari & Asnani (2017).As’ari H, Asnani DMM. The effect of administering mangosteen rind extract Garciana mangostana L. to decrease the low density lipoprotein (LDL) serum level of a white male rat with hypercholesterolemia. Dama International Journal of Researchers. 2017;2:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aukkanimart et al. (2017).Aukkanimart R, Boonmars T, Sriraj P, Sripan P, Songsri J, Ratanasuwan P, Laummaunwai P, Boueroy P, Khueangchaingkhwang S, Pumhirunroj B. In vitro and in vivo inhibitory effects of α-mangostin on cholangiocarcinoma cells and allografts. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2017;18:707–713. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azima, Noriham & Manshoor (2017).Azima AS, Noriham A, Manshoor N. Phenolics, antioxidants and color properties of aqueous pigmented plant extracts: Ardisia colorata var. elliptica, Clitoria ternatea, Garcinia mangostana and Syzygium cumini. Journal of Functional Foods. 2017;38:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boonprom et al. (2017).Boonprom P, Boonla O, Chayaburakul K, Welbat JU, Pannangpetch P, Kukongviriyapan U, Kukongviriyapan V, Pakdeechote P, Prachaney P. Garcinia mangostana pericarp extract protects against oxidative stress and cardiovascular remodeling via suppression of p47 phox and iNOS in nitric oxide deficient rats. Annals of Anatomy-Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2017;212:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buravlev et al. (2018).Buravlev EV, Shevchenko OG, Anisimov AA, Suponitsky KY. Novel Mannich bases of α- and γ-mangostins: synthesis and evaluation of antioxidant and membrane-protective activity. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2018;152:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae et al. (2017).Chae H-S, You BH, Song J, Ko HW, Choi YH, Chin Y-W. Mangosteen extract prevents dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice by suppressing NF-κB activation and inflammation. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2017;20(8):727–733. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatatikun & Chiabchalard (2017).Chatatikun M, Chiabchalard A. Thai plants with high antioxidant levels, free radical scavenging activity, anti-tyrosinase and anti-collagenase activity. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1994-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2017).Chen S, Han K, Li H, Cen J, Yang Y, Wu H, Wei Q. Isogarcinol extracted from Garcinia mangostana L. ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin lesions in mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2017;65(4):846–857. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chusri et al. (2017).Chusri S, Tongrod S, Saising J, Mordmuang A, Limsuwan S, Sanpinit S, Voravuthikunchai SP. Antibacterial and anti-biofilm effects of a polyherbal formula and its constituents against coagulase-negative and -positive staphylococci isolated from bovine mastitis. Journal of Applied Animal Research. 2017;45(1):364–372. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2016.1193021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dardak et al. (2011).Dardak RA, Halim NA, Kasa J, Mahmood Z. Challenges and prospect of mangosteen industry in Malaysia. Economic and Technology Management Review. 2011;6:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- El-Seedi et al. (2010).El-Seedi HR, El-Barbary M, El-Ghorab D, Bohlin L, Borg-Karlson A-K, Goransson U, Verpoorte R. Recent insights into the biosynthesis and biological activities of natural xanthones. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;17(9):854–901. doi: 10.2174/092986710790712147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Seedi et al. (2009).El-Seedi HR, El-Ghorab DM, El-Barbary MA, Zayed MF, Goransson U, Larsson S, Verpoorte R. Naturally occurring xanthones; latest investigations: isolation, structure elucidation and chemosystematic significance. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;16(20):2581–2626. doi: 10.2174/092986709788682056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisia et al. (2018).Elisia I, Pae HB, Lam V, Cederberg R, Hofs E, Krystal G. Comparison of RAW264.7, human whole blood and PBMC assays to screen for immunomodulators. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2018;452:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild (1915).Fairchild D. The mangosteen: “Queen of Fruits” now almost confined to Malayan Archipelago, but can be acclimated in many parts of tropics—Experiments in America—desirability of widespread cultivation. Journal of Heredity. 1915;6:339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Luo & Luo (2018).Fang Z, Luo W, Luo Y. Protective effect of α-mangostin against CoCl2-induced apoptosis by suppressing oxidative stress in H9C2 rat cardiomyoblasts. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2018;17:6697–6704. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang et al. (2016).Fang Y, Su T, Qiu X, Mao P, Xu Y, Hu Z, Zhang Y, Zheng X, Xie P, Liu Q. Protective effect of alpha-mangostin against oxidative stress induced-retinal cell death. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/srep21018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu et al. (2018).Fu T, Wang S, Liu J, Cai E, Li H, Li P, Zhao Y. Protective effects of α-mangostin against acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2018;827:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda et al. (2017).Fukuda M, Sakashita H, Hayashi H, Shiono J, Miyake G, Komine Y, Taira F, Sakashita H. Synergism between α-mangostin and TRAIL induces apoptosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity through the mitochondrial pathway. Oncology Reports. 2017;38(6):3439–3446. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendiani et al. (2017).Hendiani I, Hadidjah D, Susanto A, Pribadi IMS. The effectiveness of mangosteen rind extract as additional therapy on chronic periodontitis (Clinical trials) Padjadjaran Journal of Dentistry. 2017;29(1):64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim et al. (2018a).Ibrahim SRM, Abdallah HM, El-Halawany AM, Nafady AM, Mohamed GA. Mangostanaxanthone VIII, a new xanthone from Garcinia mangostana and its cytotoxic activity. Natural Product Research. 2018a:1–8. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1446012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim et al. (2018b).Ibrahim SR, Abdallah HM, El-Halawany AM, Radwan MF, Shehata IA, Al-Harshany EM, Zayed MF, Mohamed GA. Garcixanthones B and C, new xanthones from the pericarps of Garcinia mangostana and their cytotoxic activity. Phytochemistry Letters. 2018b;25:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2018.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim et al. (2018c).Ibrahim SR, El-Agamy DS, Abdallah HM, Ahmed N, Elkablawy MA, Mohamed GA. Protective activity of tovophyllin A, a xanthone isolated from Garcinia mangostana pericarps, against acetaminophen-induced liver damage: role of Nrf2 activation. Food & Function. 2018c;9(6):3291–3300. doi: 10.1039/c8fo00378e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim et al. (2018e).Ibrahim SRM, Mohamed GA, Elfaky MA, Al Haidari RA, Zayed MF, El-Kholy AA-E, Khedr AIM. Garcixanthone A, a new cytotoxic xanthone from the pericarps of Garcinia mangostana. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2018e:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2017.1423058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim et al. (2018d).Ibrahim SR, Mohamed GA, Elfaky MA, Zayed MF, El-Kholy AA, Abdelmageed OH, Ross SA. Mangostanaxanthone VII, a new cytotoxic xanthone from Garcinia mangostana. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 2018d;73(5–6):185–189. doi: 10.1515/znc-2017-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im et al. (2017).Im A, Kim Y-M, Chin Y-W, Chae S. Protective effects of compounds from Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen) against UVB damage in HaCaT cells and hairless mice. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2017;40:1941–1949. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaisin et al. (2018).Jaisin Y, Ratanachamnong P, Kuanpradit C, Khumpum W, Suksamrarn S. Protective effects of γ-mangostin on 6-OHDA-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. Neuroscience Letters. 2018;665:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janardhanan et al. (2017).Janardhanan S, Mahendra J, Girija AS, Mahendra L, Priyadharsini V. Antimicrobial effects of Garcinia mangostana on cariogenic microorganisms. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2017;11:19–22. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2017/22143.9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong (2016).Karim N, Jeenduang N, Tangpong J. Renoprotective effects of xanthone derivatives from Garcinia mangostana against high fat diet and streptozotocin-induced type II diabetes in mice. Walailak Journal of Science and Technology. 2016;15:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, Jeenduang & Tangpong (2018).Karim N, Jeenduang N, Tangpong J. Anti-glycemic and anti-hepatotoxic effects of mangosteen vinegar rind from Garcinia mangostana against HFD/STZ-induced type II diabetes in mice. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2018;68(2):163–169. doi: 10.1515/pjfns-2017-0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karunakaran et al. (2018).Karunakaran T, Ee GCL, Ismail IS, Mohd Nor SM, Zamakshshari NH. Acetyl- and O-alkyl-derivatives of β-mangostin from Garcinia mangostana and their anti-inflammatory activities. Natural Product Research. 2018;32(12):1390–1394. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1350666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chin & Lee (2017).Kim M, Chin Y-W, Lee EJ. α, γ-Mangostins induce autophagy and show synergistic effect with gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2017;25(6):609–617. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2017.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresnoadi et al. (2017).Kresnoadi U, Ariani MD, Djulaeha E, Hendrijantini N. The potential of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) peel extract, combined with demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft, to reduce ridge resorption and alveolar bone regeneration in preserving the tooth extraction socket. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society. 2017;17(3):282–288. doi: 10.4103/jips.jips_64_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmayadi et al. (2018).Kusmayadi A, Adriani L, Abun A, Muchtaridi M, Tanuwiria UH. The effect of solvents and extraction time on total xanthone and antioxidant yields of mangosteen peel (Garcinia mangostana L.) extract. Drug Invention Today. 2018;10:2572–2576. [Google Scholar]

- Lalitha et al. (2017).Lalitha JL, Clarance PP, Sales JT, Archana AM, Agastian P. Biological activities of Garcinia mangostana. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2017;10(9):272–278. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i9.18585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2017).Lee Kw, Ryu HW, Oh S-S, Park S, Madhi H, Yoo J, Park KH, Kim KD. Depigmentation of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-treated melanoma cells by β-mangostin is mediated by selective autophagy. Experimental Dermatology. 2017;26(7):585–591. doi: 10.1111/exd.13233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang et al. (2018).Liang Y, Luo D, Gao X, Wu H. Inhibitory effects of garcinone E on fatty acid synthase. RSC Advances. 2018;8(15):8112–8117. doi: 10.1039/c7ra13246h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin et al. (2009).Lin C-Y, Huang C-S, Huang C-Y, Yin M-C. Anticoagulatory, antiinflammatory, and antioxidative effects of protocatechuic acid in diabetic mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2009;57(15):6661–6667. doi: 10.1021/jf9015202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2018).Liu Z, Li G, Long C, Xu J, Cen J, Yang X. The antioxidant activity and genotoxicity of isogarcinol. Food Chemistry. 2018;253:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo et al. (2017).Luo M, Liu Q, He M, Yu Z, Pi R, Li M, Yang X, Wang S, Liu A. Gartanin induces cell cycle arrest and autophagy and suppresses migration involving PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK signalling pathway in human glioma cells. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2017;21(1):46–57. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machmudah et al. (2018).Machmudah S, Lestari SD, Kanda H, Winardi S, Goto M. Subcritical water extraction enhancement by adding deep eutectic solvent for extracting xanthone from mangosteen pericarps. Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 2018;133:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendra et al. (2017).Mahendra J, Mahendra L, Svedha P, Cherukuri S, Romanos GE. Clinical and microbiological efficacy of 4% Garcinia mangostana L. pericarp gel as local drug delivery in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry. 2017;8(4):e12262. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamat et al. (2018a).Mamat SF, Azizan KA, Baharum SN, Mohd Noor N, Mohd Aizat W. Metabolomics analysis of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana Linn.) fruit pericarp using different extraction methods and GC-MS. Plant Omics. 2018a;11(2):89–97. doi: 10.21475/poj.11.02.18.pne1191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamat et al. (2018b).Mamat SF, Azizan KA, Baharum SN, Noor NM, Aizat WM. ESI-LC-MS based-metabolomics data of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana Linn.) fruit pericarp, aril and seed at different ripening stages. Data in Brief. 2018b;17:1074–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazlan et al. (2018a).Mazlan O, Abdul-Rahman A, Goh H-H, Aizat WM, Noor NM. Data on RNA-seq analysis of Garcinia mangostana L. seed development. Data in Brief. 2018a;16:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazlan et al. (2018b).Mazlan O, Aizat WM, Baharum SN, Azizan KA, Noor NM. Metabolomics analysis of developing Garcinia mangostana seed reveals modulated levels of sugars, organic acids and phenylpropanoid compounds. Scientia Horticulturae. 2018b;233:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.01.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazlan et al. (2019).Mazlan O, Aizat WM, Zuddin NSA, Baharum SN, Noor NM. Metabolite profiling of mangosteen seed germination highlights metabolic changes related to carbon utilization and seed protection. Scientia Horticulturae. 2019;243:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.08.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mina & Mina (2017).Mina EC, Mina JF. Ethnobotanical survey of plants commonly used for diabetes in tarlac of central luzon Philippines. International Medical Journal Malaysia. 2017;16:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Kumar & Anal (2016).Mishra S, Kumar MS, Anal AK. Modulation of digestive enzymes and lipoprotein metabolism by alpha mangosteen extracted from mangosteen (Garcinia Mangostana) fruit peels. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences. 2016;6(1):717–721. doi: 10.15414/jmbfs.2016.6.1.717-721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moe et al. (2018).Moe TS, Win HH, Hlaing TT, Lwin WW, Htet ZM, Mya KM. Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant, antiglycation and antimicrobial potential of indigenous Myanmar medicinal plants. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2018;16(5):358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed et al. (2017).Mohamed GA, Al-Abd AM, El-Halawany AM, Abdallah HM, Ibrahim SR. New xanthones and cytotoxic constituents from Garcinia mangostana fruit hulls against human hepatocellular, breast, and colorectal cancer cell lines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2017;198:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchtaridi et al. (2018).Muchtaridi M, Afiranti FS, Puspasari PW, Subarnas A, Susilawati Y. Cytotoxicity of Garcinia mangostana L. pericarp extract, fraction, and isolate on HeLa cervical cancer cells. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2018;10:348–351. [Google Scholar]

- Muchtaridi et al. (2017).Muchtaridi M, Puteri NA, Milanda T, Musfiroh I. Validation analysis methods of α-mangostin, γ-mangostin and gartanin mixture in mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) fruit rind extract from west java with HPLC. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2017;7:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nanasombat et al. (2018).Nanasombat S, Kuncharoen N, Ritcharoon B, Sukcharoen P. Antibacterial activity of thai medicinal plant extracts against oral and gastrointestinal pathogenic bacteria and prebiotic effect on the growth of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Chiang Mai Journal of Science. 2018;45:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan et al. (2017).Narasimhan S, Maheshwaran S, Abu-Yousef IA, Majdalawieh AF, Rethavathi J, Das PE, Poltronieri P. Anti-bacterial and anti-fungal activity of xanthones obtained via semi-synthetic modification of α-mangostin from Garcinia mangostana. Molecules. 2017;22(2):275. doi: 10.3390/molecules22020275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng et al. (2018).Ng H-S, Tan GYT, Lee K-H, Zimmermann W, Yim HS, Lan JC-W. Direct recovery of mangostins from Garcinia mangostana pericarps using cellulase-assisted aqueous micellar biphasic system with recyclable surfactant. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2018;126(4):507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittayananta et al. (2018).Nittayananta W, Limsuwan S, Srichana T, Sae-Wong C, Amnuaikit T. Oral spray containing plant-derived compounds is effective against common oral pathogens. Archives of Oral Biology. 2018;90:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberholzer et al. (2018).Oberholzer I, Möller M, Holland B, Dean OM, Berk M, Harvey BH. Garcinia mangostana Linn displays antidepressant-like and pro-cognitive effects in a genetic animal model of depression: a bio-behavioral study in the flinders sensitive line rat. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2018;33(2):467–480. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-García & Peragón (2010).Ortega-García F, Peragón J. HPLC analysis of oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and tyrosol in stems and roots of Olea europaea L. cv. Picual during ripening. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2010;90(13):2295–2300. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman & Milan (2006).Osman M, Milan AR. Mangosteen Garcinia mangostana. Southampton: Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops, University of Southampton; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ovalle-Magallanes, Eugenio-Pérez & Pedraza-Chaverri (2017).Ovalle-Magallanes B, Eugenio-Pérez D, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Medicinal properties of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.): a comprehensive update. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2017;109:102–122. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan et al. (2017a).Pan T, Chen R, Wu D, Cai N, Shi X, Li B, Pan J. Alpha-mangostin suppresses interleukin-1β-induced apoptosis in rat chondrocytes by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway and delays the progression of osteoarthritis in a rat model. International Immunopharmacology. 2017a;52:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan et al. (2017b).Pan T, Wu D, Cai N, Chen R, Shi X, Li B, Pan J. Alpha-mangostin protects rat articular chondrocytes against IL-1β-induced inflammation and slows the progression of osteoarthritis in a rat model. International Immunopharmacology. 2017b;52:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panawes et al. (2017).Panawes S, Ekabutr P, Niamlang P, Pavasant P, Chuysinuan P, Supaphol P. Antimicrobial mangosteen extract infused alginate-coated gauze wound dressing. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2017;41:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2017.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parijadi et al. (2018).Parijadi AA, Putri SP, Ridwani S, Dwivany FM, Fukusaki E. Metabolic profiling of Garcinia mangostana (mangosteen) based on ripening stages. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2018;125(2):238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan et al. (2018).Phan TKT, Shahbazzadeh F, Pham TTH, Kihara T. Alpha-mangostin inhibits the migration and invasion of A549 lung cancer cells. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5027. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phunpee et al. (2018).Phunpee S, Suktham K, Surassmo S, Jarussophon S, Rungnim C, Soottitantawat A, Puttipipatkhachorn S, Ruktanonchai UR. Controllable encapsulation of α-mangostin with quaternized β-cyclodextrin grafted chitosan using high shear mixing. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2018;538(1–2):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuong et al. (2017).Phuong NTM, Van Quang N, Mai TT, Anh NV, Kuhakarn C, Reutrakul V, Bolhuis A. Antibiofilm activity of α-mangostin extracted from Garcinia mangostana L. against Staphylococcus aureus. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2017;10(12):1154–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribadi, Yonas & Saraswati (2017).Pribadi N, Yonas Y, Saraswati W. The inhibition of Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferase enzyme activity by mangosteen pericarp extract. Dental Journal. 2017;50(2):97–101. doi: 10.20473/j.djmkg.v50.i2.p97-101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Priya, Jainu & Mohan (2018).Priya VV, Jainu M, Mohan SK. Biochemical evidence for the antitumor potential of Garcinia mangostana Linn. on diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic carcinoma. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2018;14(54):186–190. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_213_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putri, Darsono & Mandalas (2017).Putri K, Darsono L, Mandalas H. Anti-inflammatory properties of mangosteen peel extract on the mice gingival inflammation healing process. Padjadjaran Journal of Dentistry. 2017;29(3):190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Qin et al. (2017).Qin Y, Sun Y, Li J, Xie R, Deng Z, Chen H, Li H. Characterization and antioxidant activities of procyanidins from lotus seedpod, mangosteen pericarp, and camellia flower. International Journal of Food Properties. 2017;20(7):1621–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Sage et al. (2018).Sage EE, Jailani N, Taib AZM, Noor NM, Said MIM, Bakar MA, Mackeen MM. From the front or back door? Quantitative analysis of direct and indirect extractions of α-mangostin from mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) PLOS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolamiero et al. (2018).Scolamiero G, Pazzini C, Bonafè F, Guarnieri C, Muscari C. Effects of α-mangostin on viability, growth and cohesion of multicellular spheroids derived from human breast cancer cell lines. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018;15(1):23–30. doi: 10.7150/ijms.22002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodata et al. (2017).Sodata P, Juntavee A, Juntavee N, Peerapattana J. Optimization of Adhesive Pastes for Dental Caries Prevention. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(8):3087–3096. doi: 10.1208/s12249-017-0750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita et al. (2017).Sugita P, Arya S, Ilmiawati A, Arifin B. Characterization, antibacterial and antioxidant activity of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) pericarp nanosized extract. Rasayan Journal of Chemistry. 2017;10(3):707–715. doi: 10.7324/rjc.2017.1031766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan et al. (2017).Tan GYT, Zimmermann W, Lee K-H, Lan JC-W, Yim HS, Ng HS. Recovery of mangostins from Garcinia mangostana peels with an aqueous micellar biphasic system. Food and Bioproducts Processing. 2017;102:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2016.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk et al. (2017).Tarasuk M, Songprakhon P, Chimma P, Sratongno P, Na-Bangchang K, Yenchitsomanus P-t. Alpha-mangostin inhibits both dengue virus production and cytokine/chemokine expression. Virus Research. 2017;240:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjahjani (2017).Tjahjani S. Antimalarial activity of Garcinia mangostana L. rind and its synergistic effect with artemisinin in vitro. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1649-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousian Shandiz, Razavi & Hosseinzadeh (2017).Tousian Shandiz H, Razavi BM, Hosseinzadeh H. Review of Garcinia mangostana and its xanthones in metabolic syndrome and related complications. Phytotherapy Research. 2017;31(8):1173–1182. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai et al. (2016).Tsai S-Y, Chung P-C, Owaga EE, Tsai I-J, Wang P-Y, Tsai J-I, Yeh T-S, Hsieh R-H. Alpha-mangostin from mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana Linn.) pericarp extract reduces high fat-diet induced hepatic steatosis in rats by regulating mitochondria function and apoptosis. Nutrition and Metabolism. 2016;13(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udani et al. (2009).Udani JK, Singh BB, Barrett ML, Singh VJ. Evaluation of mangosteen juice blend on biomarkers of inflammation in obese subjects: a pilot, dose finding study. Nutrition Journal. 2009;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese et al. (2017).Varghese GK, Abraham R, Chandran NN, Habtemariam S. Identification of lead molecules in Garcinia mangostana L. against pancreatic cholesterol esterase activity: an in silico approach. Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences. 2017:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12539-017-0252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2018a).Wang A, Li D, Wang S, Zhou F, Li P, Wang Y, Lin L. γ-Mangostin, a xanthone from mangosteen, attenuates oxidative injury in liver via NRF2 and SIRT1 induction. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018a;40:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2018b).Wang W, Liao Y, Huang X, Tang C, Cai P. A novel xanthone dimer derivative with antibacterial activity isolated from the bark of Garcinia mangostana. Natural Product Research. 2018b;32(15):1769–1774. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1402315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2017).Wang F, Ma H, Liu Z, Huang W, Xu X, Zhang X. α-Mangostin inhibits DMBA/TPA-induced skin cancer through inhibiting inflammation and promoting autophagy and apoptosis by regulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in mice. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017;92:672–680. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. (2017).Wu C-P, Hsiao S-H, Murakami M, Lu Y-J, Li Y-Q, Huang Y-H, Hung T-H, Ambudkar SV, Wu Y-S. Alpha-mangostin reverses multidrug resistance by attenuating the function of the multidrug resistance-linked ABCG2 transporter. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2017;14(8):2805–2814. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]