Intestinal type gastric cancer develops in the background of preceding mucosal changes including parietal cell atrophy and two metaplastic processes: spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) and intestinal metaplasia (IM).1 H pylori eradication decreases the risk of gastric cancer significantly,2 but the continued presence of metaplasia carries an extended risk for cancer development. The metaplastic lesions established in long-term infection may be resistant to eradication therapy and continue to promote gastric carcinogenesis even after eradication.3 Therefore, prevention of gastric cancer requires regression of metaplastic lesions.

We have previously reported that expression of activated Ras in stomach chief cells of Mist1-CreERT2;LSL-Kras(G12D) mice (Mist1-Kras mice) leads to evolution of SPEM and then IM.4 Administration of Selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY-142886), an inhibitor of MEK, induced regression of metaplasia and promoted the repopulation of the corpus mucosa with normal cell lineages.4 Previous studies have documented Ras activation increases in metaplastic lesions in mice and humans infected with H pylori and in at least 40% of intestinal-type gastric cancers.5-8 We have therefore now sought to evaluate whether Selumetinib treatment can ameliorate metaplasia induced by H pylori infection.

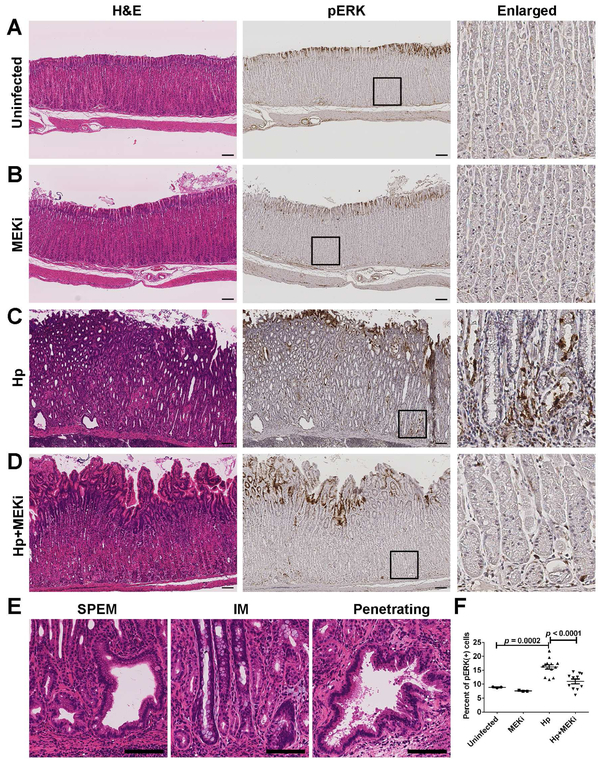

Mongolian gerbils develop both SPEM and IM following chronic infections with H pylori for greater than 6 months.9 We used H pylori-infected gerbils to determine the effects of Selumetinib treatment. After one year of H pylori infection, gerbils were randomly assigned to receive implantation of either placebo subcutaneous pellets (n=13) or Selumetinib-containing slow release pellets (n=11) for a total of 4 weeks of dosing. In the gastric corpus mucosa of uninfected gerbils, phospho-ERK1/2 positive cells were located at the surface of mucosa (Figure 1A). Selumetinib treatment in uninfected gerbils did not change the morphology of the corpus glands (Figure 1B). H pylori-infected gerbils with placebo treatment showed severe parietal cell loss and extensive metaplasia throughout the gastric corpus (Figure 1C). Glands with various types of architectural aberrations were observed, including branched lesions and dilated lesions with metaplasia and extensive lesions with glands penetrating into the submucosa (Figure 1E). Phospho-ERK1/2 staining was observed not only in surface mucous cells, but also in SPEM cells at bases of glands (Figure 1C). Nevertheless, H pylori-infected gerbils treated with Selumetinib showed decreases in SPEM and re-establishment of the oxyntic glands in the corpus mucosa, with loss of phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity at the gland bases (Figure 1D). The percentage of phospho-ERK1/2 positive cells decreased significantly compared with the placebo treated gerbils (Figure 1F). These findings demonstrate that the Selumetinib treatment was successful in reducing H pylori-induced MEK activation.

Figure 1. Morphological changes and inhibition of phospho-ERK1/2 by Selumetinib treatment.

(A-D) Immunohistological staining of corpus mucosa of gerbils from untreated group (Uninfected, n=3), only Selumetinib treatment group (MEKi, n=3), H pylori-infected with placebo treatment group (Hp, n=13), and H pylori-infected with Selumetinib treatment group (Hp+MEKi, n=11). Left panel: H&E stain, middle panel: phospho-ERK1/2 stain. Boxes denote enlarged region in the right panel. (E) Morphological changes in gerbil gastric corpus mucosa following H pylori infection. Scale bars: 100 μm. (F) Phospho-ERK1/2-positive cell populations quantified in each of the four groups (mean+SD). ANOVA p<0.001. Statistical differences between groups were determined by Fisher’s LSD test.

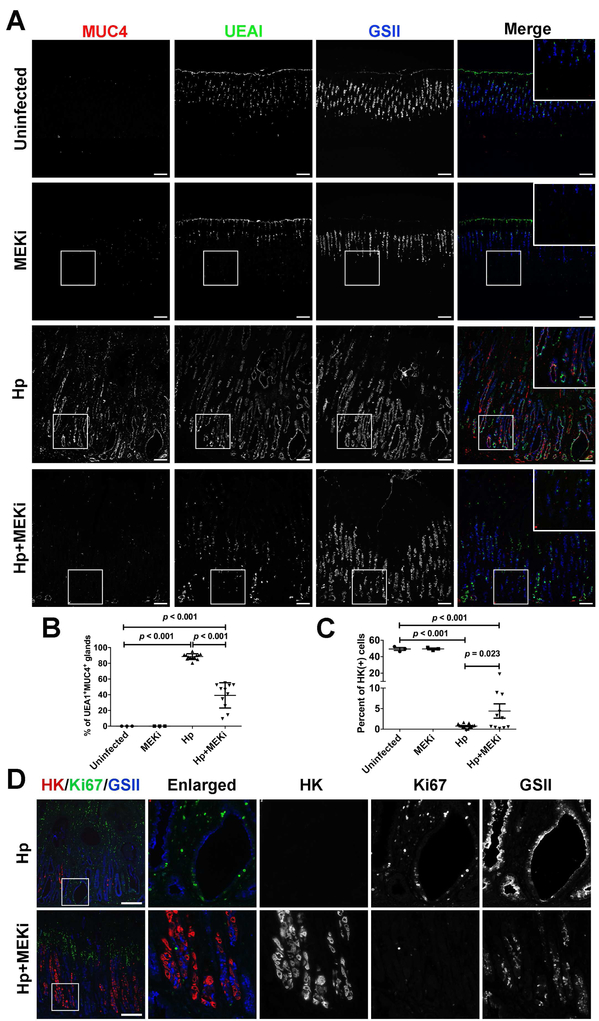

We evaluated the expression of metaplasia markers in the gastric mucosa. We have previously noted the expression of MUC4 in advanced metaplasia in H pylori-infected gerbils.10 We examined the expression of Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA1) together with two other SPEM markers in gerbil (MUC4 and GSII). In uninfected gerbils, UEA1 was expressed in the surface mucus cells (Figure 2A). This expression pattern was not changed by Selumetinib treatment in uninfected gerbils. However, after H pylori infection, expression of UEA1 extended from the surface of mucosa to the bottom of glands, co-localizing with MUC4 and GSII (Figure 2A). Goblet cell IM showed co-staining with MUC4 and MUC2 (Supplementary Figure 1). UEA1 was absent from MUC2 positive cells, but was observed in SPEM glands with MUC4 (Supplementary Figure 1). After Selumetinib treatment, all of the three SPEM markers (UEA1, MUC4 and GSII) were decreased significantly at the bases of glands (Figure 2A). Although some glands with UEA1 and/or GSII remained, the UEA1-MUC4 double positive glands decreased significantly compared with placebo treatment (Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that Selumetinib can inhibit SPEM even in the continued presence of H pylori infection.

Figure 2. Inhibition of H pylori-induced metaplasia by MEK inhibition.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of gerbil gastric corpus mucosa from Uninfected, MEKi, Hp and Hp+MEKi groups. Red: MUC4, green: UEA1 and blue: GSII. (B) Percentage of UEA1 and MUC4 double positive glands as a reflection of advanced metaplasia quantified in all four groups (mean+SD). ANOVA p<0.001. (C) H/K-ATPase-positive cell populations quantified in all four groups (mean+SD). ANOVA p<0.001. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of gerbil gastric corpus mucosa from Hp and Hp+MEKi groups. Red: H/K-ATPase, green: Ki-67 and blue: GSII. Scale bars: 100 μm. Statistical differences between groups were determined by Fisher’s LSD test.

To evaluate the return of normal lineages more quantitatively, we evaluated parietal cells and the proliferating cells using immunostaining. Untreated H pylori-infected gerbils showed severe loss of parietal cells and proliferative cells were present diffusely throughout the mucosa (Figure 2C, D). After Selumetinib treatment, we observed a small, but significant, increase in parietal cells mainly located in the basal regions of glands and the proliferative zone was consolidated in a region luminal to the parietal cells (Figure 2C, D). We also examined the presence of chief cells using intrinsic factor (IF) in gerbils from the four different groups. In uninfected gerbils, IF-positive chief cells were located at the bases of corpus glands (Supplementary Figure 2A) and MEK inhibitor treatment did not change the number or distribution of chief cells (Supplementary Figure 2B). After H pylori infection, the number of IF expressing chief cells was reduced dramatically (Supplementary Figure 2C). Following Selumetinib treatment, we observed the re-emergence of IF-positive chief cells at the bases of glands (Supplementary Figure 2D). Finally, we evaluated the presence of TFF2-expressing cells in H pylori -infected gerbils without or with Selumetinib treatment. H pylori-infected gerbil stomachs showed TFF2-staining of SPEM cells (Supplementary Figure 3). However, after Selumetinib treatment, TFF2-staining was now observed in smaller triangular cells, a morphology characteristic of normal mucous neck cells. Our results indicate that MEK inhibitor treatment led to the re-emergence of normal gastric lineages.

This study demonstrates that blockade of the MAPK signal pathway by a MEK inhibitor, Selumetinib, induces arrest of metaplasia and re-establishment of normal gastric corpus lineages even with continuing H pylori infection. These results confirm our previous findings in mice that Ras activation drives the formation of SPEM and concomitant suppression of normal corpus progenitor activity.4 In the mouse studies, elimination of metaplasia and repopulation of the stomach with normal gastric lineages continued after cessation of Selumetinib treatment. H pylori eradication therapy is increasingly used as a preventative strategy for gastric cancer, and may reduce the cancer incidence rate by as much as 50%.2, 11, 12 Nevertheless, in patients with Stage I gastric cancer who have undergone endoscopic submucosal resection, the risk of developing secondary gastric cancer from remaining metaplastic tissues even after eradication therapy is reported at 2-5% per year.13, 14 Thus, a risk of cancer remains even after eradication of H pylori.15 Future studies should investigate the combined impact of MEK inhibition and H pylori eradication on progression of metaplasia in the stomach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by grants from a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award IBX000930 and NIM RO1 DK071590 and RO1 DK101332 (to J.R.G), from DOD W81XWH-17-1-0257, AACR 17-20-41-CHOI and pilot funding from NIM P30 DK058404 (to E.C). Q.Y. received financial support from the China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 201706225033). This work was supported by core resources of the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Center, (P30 DK058404) the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485), and imaging in the Vanderbilt Digital Histology Shared supported by a VA Shared Instrumentation grant (1IS1BX003097).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldenring JR, et al. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2207–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi IJ, et al. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1085–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato M, et al. Dig Endosc 2013;25:264–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi E, et al. Gastroenterology 2016;150:918–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Nature 2014;513:202–9.25079317 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cristescu R, et al. Nat Med 2015;21:449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sierra JC, et al. Gut 2018;67:1247–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobert AP, et al. J Immunol 2011;187:5370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshizawa N, et al. Lab Invest 2007;87:1265–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu T, et al. J Pathol 2016;239:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee YC, et al. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1113–1124 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doorakkers E, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosaka T, et al. Dig Endosc 2014;26:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pimentel-Nunes P, et al. Endoscopy 2014;46:933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malfertheiner P, et al. Gut 2017;66:6–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.