Abstract

The disproportionate burden of HIV among women in sub-Saharan Africa reflects underlying gender inequities, which also impact patient-provider relationships, a key component to retention in HIV care. This study explored how gender shaped the patient-provider relationship and consequently, retention in HIV care in western Kenya. We recruited and consented 60 HIV care providers from three facilities in western Kenya affiliated with the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH). Trained research assistants conducted and audio recorded 1-h interviews in English or Swahili. Data were transcribed and analyzed in NVivo using a structured coding scheme related to provider and patient gender. Gender constructs, as culturally defined, emerged as an important barrier negatively impacting the patient-provider relationship through three main domains: (1) challenges establishing clear roles and sharing power due to conflicting gender versus patient/provider identities, (2) provider frustration over suboptimal patient adherence resulting from gender-influenced contextual barriers, and (3) negative provider perceptions shaped by differing male and female approaches to communication. Programmatic components addressing gender inequities in the health care setting are urgently needed to effectively leverage the patient-provider relationship and fully promote long-term adherence and retention in HIV care.

Keywords: HIV, gender, patient-provider relationship, retention, Kenya

Resumen:

La prevalencia desproporcionada del VIH entre las mujeres en África subsahariana refleja las desigualdades subyacentes del género que también impactan la relación entre pacientes y proveedores, un componente clave para la retención en la atención del VIH. Este estudio exploró cómo el género influye la relación paciente-proveedor y, en consecuencia, la retención en la atención del VIH en el oeste de Kenia. Se reclutaron y otorgaron el consentimiento a proveedores de atención de VIH (N=60) de tres centros afiliados con el Modelo Académico Promocionando Acceso a la Salud (AMPATH) en el oeste de Kenia. Personal capacitado llevó a cabo entrevistas a profundidad en inglés o suajili. Las mismas fueron grabadas, transcriptas y codificadas en NVivo, y se realizó un análisis inductivo temático. Los constructos de género, definidos culturalmente, surgieron como una barrera importante que impacta negativamente la relación paciente-proveedor a través de tres temas principales: 1) desafíos debido a conflictos de identidad entre el género y el rol de paciente/proveedor, 2) frustración del proveedor con pacientes con dificultades de adherencia debido a barreras contextuales influenciadas por el género, y 3) las percepciones negativas del proveedor formadas de pacientes masculinos y femeninos por las diferentes formas de comunicación debido al constructo de género. Se necesitan con urgencia el desarrollo de programas que aborden las desigualdades de género en la atención del VIH para optimizar la relación paciente-proveedor y al hacer eso, fortalecer la adherencia y la retención a largo plazo en la atención del VIH.

Introduction

Gender inequities place women at increased risk of HIV infection (1, 2), and heterosexual epidemics have been found to be significantly associated with gender inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (3) and at the global level (4). In Kenya, HIV prevalence among women is 7.6% compared to 5.6% in men (5). While women are at higher risk of HIV infection, men have lower rates of service utilization including lower HIV testing rates, less contact with HIV clinical settings, and less knowledge about HIV compared to women (6). This is reflected in significantly lower linkage and retention to HIV care among males (7, 8). Efforts to identify and target factors impacting engagement in care are critical to controlling the epidemic.

HIV accentuates gender inequities, power differentials, and differences in sexual agency between men and women (9–11). Raewyn Connell’s theories surrounding gender and power, specifically hegemonic masculinity and acquiescent femininity, have facilitated a greater understanding of gender dynamics in the HIV epidemic. Jewkes & Morrell apply this framework in SSA to help explain the role of gender in the HIV epidemic in highly gender-inequitable countries (9, 12–15). Here, hegemonic masculinity and acquiescent femininity serve as social constructs that lend status to men and legitimize the subordination of women (14). These constructs shape individual behavior and relationships and constrain decision-making not only at the family and community levels but also in the healthcare context and patient-provider relationship.

The patient-provider relationship is also shaped by a separate set of norms in the health care setting, which lend status to individuals in a fashion similar to gender. By accessing specialized training, providers gain status as health care professionals, and this creates power differentials in the patient-provider relationship (16). In Kenya, a paternalistic model is typical in which the patient assumes the provider possesses specialized knowledge and therefore minimally participates and does not contribute actively to treatment beyond describing initial symptoms (17). Thus, the patient-provider relationship is shaped within and subject to both gender and health care setting norms.

Gender has contributed to disparities in provider perceptions in several settings. Providers have been found to express greater frustration and negative attitudes towards female patients compared to males (18), perhaps due to differences in communication in the clinic (19–21), and other gender-related influences that create implicit biases in delivery of care (22). This is critical as provider perceptions and attitudes impact decisions surrounding treatment (23, 24). Moreover, the patient-provider relationship is a key factor to retention in HIV care (25–27).

Thus, understanding how providers perceive and experience gender, and how it shapes the patient-provider relationship may provide insight into patient behavior and gaps in HIV care. Furthermore, understanding the role of gender on the patient-provider relationship may enhance its role as a facilitator for retention, which is critical to achievement of the 90–90-90 goals. However, while studies have extensively explored the influence of gender on the HIV epidemic, the role of gender in patient-provider relationships has not been characterized in this region to date. This study is among the first to explore the impact of culturally defined gender norms on the patient-provider relationship in the context of HIV care in Kenya.

Methods

Study Design

This was a qualitative analysis focused on gender nested within a larger qualitative study consisting of in-depth interviews with HIV care providers conducted between September 2014-August 2015 in western Kenya to understand barriers and facilitators to engagement in care from the provider perspective.

Study setting

This study was conducted at three clinical sites affiliated with AMPATH (Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare), a partnership initiated in 2001 between Moi University’s School of Medicine, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH), and a consortium of universities in the US and Canada. AMPATH currently supports care for nearly 100,000 HIV-infected patients in eight counties throughout western Kenya and has evolved to embrace a holistic approach to care by providing a range of services including nutrition assistance, primary care, chronic disease management, and agricultural programs. AMPATH provides HIV- and tuberculosis-related care free of charge. Patients usually return to the same clinic for HIV care but are unlikely to see the same nurses and clinical officers at each visit as they are seen in the order they arrive by the first available clinician. However, peripheral support providers are more likely to see the same patients over time. Frequency of patient encounters range from two weeks to six months and depend on patient’s health status, adherence patterns, length in care, and socioeconomic status. This study recruited participants from one urban (MTRH in Eldoret, population: 252,000) and two semi-rural (Webuye, population: 22,000; Busia, population: 50,000) AMPATH sites.

Study population

We targeted HIV care providers including clinical officers, nurses, HIV counselors, and peripheral support providers such as nutritionists, social workers, and psychosocial/outreach workers. Clinical officers are medically-trained, mid-level professionals responsible for delivery of primary care and ART, while nurses largely comprise the frontline staff. Both clinical officers and nurses receive post-secondary education in medical training colleges certified by the Kenyan government. Clinical officers spend three years in college, while nurses spend one to three years depending on their specialization. Individuals were considered eligible for participation if they were at least 18 years of age and had been employed by AMPATH to deliver HIV care or testing for at least 6 months.

Recruitment

We used purposive sampling to identify participants and stratified by occupation (four categories: Clinical officer, Nurse, Counselor, and Peripheral support provider), and urban/semi-rural setting, aiming to recruit different types of providers in each setting (N=60). We reviewed staffing lists and consulted program managers at each recruitment site to identify HIV care providers that met our eligibility criteria and invited them to participate in a one-hour interview. All those approached agreed to participate. Investigators introduced the study, obtained written consent, and compensated participants with a lunch voucher of 500 KES (6 USD).

Ethics Approval

Approval of the study protocol was obtained from both the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee (IREC) at Moi University and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Brown University. Privacy and confidentiality were maintained at all times by conducting interviews in private, off-site locations, and de-identifying all interviews before destroying audio recordings.

Data collection

Three trained female research assistants conducted 60 in-depth audio-recorded interviews lasting about an hour in English or Swahili. Interviews took place in quiet, private rooms off-site. Interview guides were derived from the socio-ecological model (28) to explore patient-provider relationships, communication, and provider perspectives on facilitators and barriers to HIV care through five main domains: 1) patient factors, 2) patient-provider communication, 3) clinic factors, 4) system factors, and 5) provider factors. Provider perspectives on gender were specifically explored in ‘patient factors’ when providers were asked about particular challenges faced with male and female patients. Gender was not specifically probed in other domains, though was addressed indirectly, for example, through exploring what kinds of patients typically missed or came late to appointments, characteristics of non-adherent and less engaged patients, as well as provider perspectives about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ patients, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ patient relationships, clinic accessibility, and cultural constraints. Questions were written in English, translated to Swahili, and back translated to English for consistency.

Data Analysis

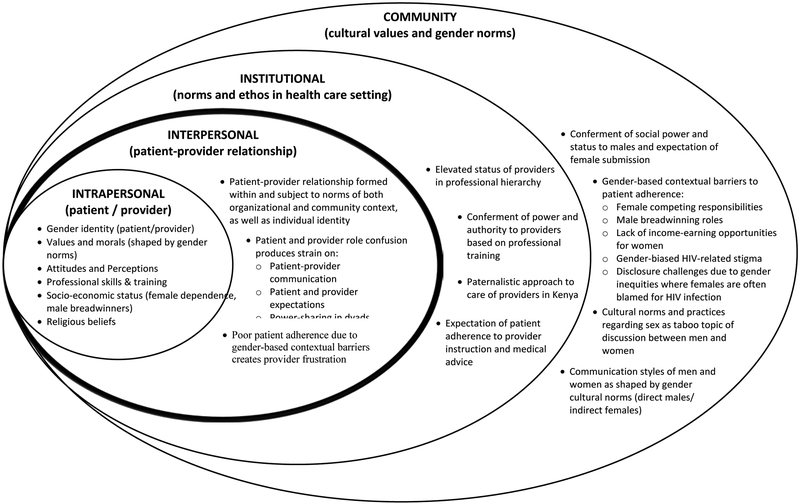

Data were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo 8 (29) for coding and analysis. A two-stage coding process was applied. First, three investigators independently coded and reconciled 12 interviews following a structured coding scheme to organize the results by the five domains in the interview guide, and a final codebook was established. Two additional research assistants were then trained to code transcripts, applying the codebook and adding new codes as they emerged. Second, a gender-based conceptual model (Figure 1), based on the socio-ecological framework (28), was developed and utilized to guide inductive thematic analysis (30) and code all transcripts, identifying themes as they emerged. Results were then organized within the main structure of the model to visualize and understand the relationships between gender-related themes at each level of analysis: intrapersonal (individual patient or provider identities and characteristics), interpersonal (patient-provider relationship), institutional (professional norms and ethos), and community (cultural values and gender norms).

Figure 1:

Conceptual map of gender and the patient-provider relationship

Results

Study Sample

Characteristics of the 60 HIV care providers are shown in Table 1. The average age and years delivering HIV care were similar among male and female providers. Almost all participants (59/60) had at least some post-high school education, with a majority possessing the equivalent of a community college course certificate or degree. Most nurses (17/18) and counselors (8/10) were female, with fairly even gender distributions among clinical officers and peripheral support workers.

Table 1:

Study sample characteristics

| Characteristics | Women (N=43) | Men (N=17) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD (year) | 39.1 ± 6.1 | 37.4 ± 8.3 |

| Mean years worked in HIV care ± SD | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 7.5 ± 2.0 |

| Highest Educational Attainment (N (%)) | ||

| O Level (high school diploma) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Diploma or Certificate (1-3 years community college) | 29 (67) | 13 (76) |

| Undergraduate Degree | 12 (28) | 3 (18) |

| Postgraduate | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Occupation | ||

| Clinical officer | 9 (21) | 7 (41) |

| Nurse | 17 (39) | 1 (6) |

| Counselor | 8 (19) | 2 (12) |

| Peripheral support providers | 9 (21) | 7 (41) |

| Site | ||

| MTRH (Eldoret) | 25 (58) | 5 (30) |

| Webuye | 9 (21) | 6 (35) |

| Busia | 9 (21) | 6 (35) |

Overview of Main Findings

Gender-related themes emerged at the community, institutional, interpersonal, and intrapersonal levels of analysis (Figure 1). Findings revealed that gender norms and sociocultural values at the community level interact dynamically with norms in the clinical setting in ways that negatively impact the patient-provider relationship, which is formed at the interpersonal level within both larger contexts. Results indicated three main themes through which this occurred: 1) difficulty establishing clear, harmonious roles and sharing power due to conflicting gender versus patient/provider identities in the clinic setting, 2) provider frustration over patient non-adherence owing to contextual barriers related to gender, 3) suboptimal patient-provider communication resulting from perceived differences in male and female communication styles. These themes will be described in greater detail in the following section.

Theme 1: Gender and Professional Identity: Conflicts in Role Clarity and Sharing Power in Patient-Provider Dyads

Providers discussed difficulties establishing and asserting their professional role with patients due to conflicts with gender identity. While Kenyan social norms confer power to men, providers are awarded status through professional training and medical/field expertise in the health care setting. Thus, conflicts arose in the patient-provider relationship, formed within and impacted by both contexts. Both male and female providers faced challenges due to competing gender and professional norms.

Challenges reconciling professional and gender role

Male providers faced challenges in establishing clear roles in the clinic. Accustomed to positions of clear authority and social power, male providers were limited by their personal gender lens and consequently had less patience for female patients that did not acquiesce to these expectations.

‘Then she comes with all that pride, with all that, then I ask her mama in fact you are late for the date, you are late with time. We are ready to serve you but the way you are behaving is not so good. So you see, some women have quick answers and me I am a man. Quick answers provoke strife. So we talked, I tried to negotiate and she is just like “in fact I will never come back again” then she left’ [Male Clinical Officer].

Inability to separate power conferred by gender versus professional role in this case may have directly contributed to patient drop out.

Role confusion also emerged when female providers disrupted expectations of deference with male patients who recognized them as women and not as trained professionals. Male patient perspectives about gender appeared to contribute to difficulties establishing harmonious, productive relationships.

‘[Men] don’t want to be told their mistakes. This is a community, women have to submit. Sometimes when you try to explain to them they don’t see you as a care provider they see you as a woman and a woman has no say in the community.’ [Female Nurse].

The refusal of male patients to recognize and respect the clinical knowledge and authority of female providers was frustrating and they described difficulties fulfilling their roles as a result. For example, challenges establishing clear roles and sharing power with patients severely limited the capacity of female providers to deliver proper counseling, education and HIV care.

‘This man came and the man said, actually he had a condom burst and he couldn’t know as to why. So I was asking could I now teach you how to use a condom. He was telling me how can you teach me and you don’t use it. So I was like “fine I’m a lady, I don’t use male condom but I have education about it.” He was saying “no, it is me who knows better because I’m the one who uses it.”‘ [Female Counselor].

Gender also hindered provider ability to establish professional boundaries. Female providers attempting to provide comprehensive care and support to male patients reported unwanted sexual attention, which complicated the patient-provider relationship.

‘[Challenges] for men’s session, you see when we are counseling men, sometimes they can go to that deeper side of even seducing you, so it’s sometimes risky…they say many after the session... “Leave the phone number. Maybe when we’ll be having issues we’ll be calling you.” So when they are there, they are like, “I like you, I want to have a relationship with you,”‘ [Female Counselor].

Another female provider reported changing her phone number to end inappropriate calls. Restricted communication places additional strain on the patient-provider relationship and complicates the delivery of high-quality patient care.

Gender limitations on patient-provider discussion of sex

Gender also limited the ability of providers to fulfill their professional roles by restricting open discussion of sex in dyads where patients and providers were of the opposite sex. Kenyan cultural norms treat sex as a taboo subject for discussion between men and women and this affected patient perceptions. Providers noted this was a challenge in organizing patient support groups, encouraging educational discussions about care, and giving medical counsel for prevention of partner transmission. Any dialogue involving sex required grouping patients and patient-provider dyads by gender, which complicated care delivery.

‘The challenge we have which I normally see with men is about their culture, especially like the Kalenjin if you talk about condoms you see a person does not want to listen, especially men and you know being intimate is what is there if you talk to them about sex, they see it is like you are talking of bad things’ [Female Psychosocial Officer].

In many cases, providers shared that the inability to discuss sex due to patients’ gendered perceptions had significant implications for patient care and health outcomes.

‘We might also be talking about last menstrual period, because you may be pregnant and when you are pregnant we would like to look at you with the baby…my most embarrassing moment was not so long ago. Eventually after explaining to her, she was remorseful…in fact she was embarrassed because she was actually having problems with her periods which also ended up with her needing a gynecologist.’ [Male Clinical Officer].

Provider inability to establish trust and create an environment where patients felt comfortable discussing health issues without shame or embarrassment due to gender differences created real delays in care.

‘When we are in the support session, especially women’s session, we’ve come up with so many issues with women but in the clinic, it can’t be identified because most of them cannot tell the doctor.’ [Female Counselor].

Providers noted that women especially felt uncomfortable with their opposite-gender providers, only later identifying problems among same-gender peers.

Theme 2: Negative attitudes and perceptions of women with poor adherence and retention compared to men

Frustration with adherence issues among women compared to men

Both male and female providers expressed frustration over poor patient adherence to ART and rentention in HIV care, often attributing this behavior to gender-related contextual barriers and forming negative attitudes and perceptions towards these, mostly female, patients. Women were described as more likely to exhibit poor adherence, arrive late or miss appointments, and providers perceived them to be less engaged in their care compared to men, which was considered a nuisance in this high-volume clinic setting with a shortage of staff.

‘Women fail to attend clinics and most of their reasons is that they forgot or they lacked fare. But for men they put the date on their minds and they miss for a certain reason, but for women they will say they forgot…They are more stressed than men and don’t have a source of income. And maybe they have children so they bear all the responsibilities…they miss clinic the most and are not adherent.’ [Male Psychosocial Worker].

Providers described becoming impatient with common “excuses” like forgetting clinic or ART due to competing responsibilities and child care, relying on partners for transport fare because of a lack of access to income-earning opportunities, and minimal engagement due to not having disclosed to partners.

Female patients with poor adherence and/or retention perceived as dishonest and uncommitted to care

In situations of poor adherence and retention, providers described female patients as evasive and more likely to lie and make excuses.

‘Late comers…women do not keep their appointments. Although men are impatient they attend clinics more than women and they keep their appointments…women like giving excuses, “oh I didn’t come last week because my baby was sick, I didn’t have transport.” You know, it gets annoying because if every time you miss the clinic you give the same excuse, surely we get tired.’ [Female Clinical Officer].

Providers thus formed negative attitudes towards women, perceiving them as dishonest and less invested in and committed to their care compared to men.

‘You can just tell from their physical appearance that this person will not be taking their medication well, mostly the women. Men, they fail to come to the clinic but they make sure they take their meds. But women, they just lie to you. So there’s a bit of commitment on the men’s side compared to the women’s side.’ [Female Social Worker].

Male reasons for poor adherence and/or retention perceived to be more acceptable and valid

In general, men’s reasons for poor adherence and retention, namely breadwinning responsibilities, tended to be viewed more legitimately compared to women. Though providers were also frustrated with the time constraints caused by such responsibilities, they perceived these scheduling issues as valid.

‘Men as breadwinners you know they are very busy and the time you have to meet them is minimal unlike women. Most of the times they go to work. They don’t have time so they will want to leave early during a session and that is not good because as a counsellor when a client hurries you up you will not help him to the level that is required.’ [Male Psychosocial Worker].

Disapproval of sex work and promiscuity as response to gendered contextual barriers

Providers also disapproved of how women responded to gender-related contextual barriers, namely lack of access to income-earning opportunities. Providers shared stories of women who lost all familial and partner support upon disclosure of their status, including their homes, and began sex work as a means of survival. Many providers blamed, judged and expressed shame in response to this promiscuous behavior.

‘She said, “If you were in this situation and accept who you are, you’ll do what I’m doing.” So I was like, “Ok,” because to me I don’t think I can do that…I felt like judging this woman.’ [Female Nurse].

Providers also felt morally conflicted by female patients portrayed to engage in sexually risky behavior and yet were dishonest with partners about their status. Their personal reservations presented challenges to delivering care effectively.

‘[Challenges specific to women include] single women, they do a lot of cheating [lying] you don’t know what to do because you know what they are doing is wrong.’ [Female Nurse].

Providers also noted feeling overwhelmed by these patients and that their efforts to deliver care were futile.

‘At times you feel depressed too because you wonder why this is happening…you get a scenario where you have a mother who has 8 children born from different fathers and is very alcoholic. She is not employed, she stays somewhere as a squatter, and she keeps getting children and when you inquire she is not married. You try until you give up.’ [Male Clinical Officer].

Providers were aware of the myriad of gender-related contextual barriers faced by female patients, affecting and constraining their care decisions, though still tended to form negative attitudes toward women with suboptimal adherence and retention resulting from these challenges. Though providers described situations of poor male adherence and retention due to breadwinning roles, these reasons tended to be considered valid and not within patient control, in contrast to individual irresponsibility in the case of women.

Theme 3: Different male and female communication styles in the clinic impact provider perceptions and interactions with patients

Provider narratives revealed different perceptions of male and female patients based on their approach to communication and behavior in the clinic. Culturally-defined gender roles in Kenya and idealization of acquiescent femininity constrain women to portray a passive, indirect approach to communication in contrast to the more direct and dominant style of men. These gender ideals as manifested by patients in the clinic appeared to negatively shape provider perceptions. Female patients were portrayed as evasive, indirect, manipulative and emotional, while men were described as arrogant and entitled. In both cases, gender appeared to influence communication in ways that frustrated providers and strained the patient-provider relationship.

Perceptions of indirect female versus direct male approach to communication

Providers described discouragement with the passive way female patients handled dissatisfaction with their care, rather than voicing these concerns directly.

‘Women they might not talk but you may see actions…they’ll not talk to you directly but…you’ll know you’ve irritated them but they rarely confront you.’ [Female Nurse].

In contrast, men were described as honest and forthcoming in their communication with providers, which enabled positive relationships.

‘You know with a male client when you ask him he’ll tell you…honestly…but a woman they will beat around the bush, but for men when you insist he’ll tell you the truth. Men tend to tell the truth more than women.’ [Female Nurse].

This indirect manner of female patient communication was interpreted as dishonesty and negatively affected provider perceptions of women.

Challenges with female emotional temperament

Providers also noted that women tended to be more sensitive and emotionally unstable patients compared to men, often dealing with personal issues in their families and communities that resulted in frequent crying at clinic and challenges in delivering care.

‘Women have very many personal issues that make them emotional. So sometimes you are attending to them and they just break down, this makes it very hard for us to serve them.’ [Female Clinical Officer].

Some providers characterized women’s emotional displays as manipulative, and doubted patient investment and sense of ownership in treatment.

‘Women like complaining, they like making themselves look very poor…basically women like sympathy.” [Female Nutritionist].

These attitudes towards female patients made the construction of positive patient-provider relationships difficult.

Challenges with male aggression

Conversely, male patients were described as direct, aggressive, and impatient, demanding immediate attention in the clinic. Both male and female providers expressed frustration with their “arrogance” and entitlement.

‘Men are also impatient, not just impatient, very impatient. You know when women come, they know it’s their clinic day and they queue up waiting to be served. But men…they come in, they want to push everyone around and they have this common line they use, “you know we are going to look for means of feeding our families.”‘ [Female Clinical Officer].

While providers considered breadwinning responsibilities to be a legitimate explanation for occasional slips in adherence, in the context of clinical encounters they expressed annoyance over its use as an excuse for male patients’ aggressive approach. Impatient attitudes also contributed to men investing less time and expressing minimal interest in counseling or discussing their care, which prevented growth of a positive patient-provider relationship.

‘When it comes to men, men don’t like talking much in the session. They don’t like the counseling part of it. Most men [just] want the testing part of it. It’s like you are wasting their time.’ [Male Counselor].

This impatience reduced provider motivation to provide care.

‘Men can be very impatient, they are irritating, they can utter words that can irritate you and make you feel like not serving them. Others are just intimidating.’ [Female Nurse].

Male aggression and intimidation fostered resentment, unhealthy patient-provider relationships, and compromised care delivery.

Discussion

The main findings of this study indicated that gender negatively impacts patient-provider relationships through several pathways. Sociocultural gender constructs contributed to poor role clarity and division of power between patients and providers, biased perceptions of female patients with poor adherence compared to males, and suboptimal communication in the clinic.

Our findings are consistent with research in other settings identifying gender as a critical sociocultural factor influencing patient-provider interaction. Studies have found different healthcare communication practices among male and female patients (19–21), as well as disparities in patient-provider interactions such as content discussed (31, 32), services provided (31), question asking (32), and partnership building (32). Patients have also been found to prefer providers of the same gender, affecting patient satisfaction levels (33). A study in Kenya among health care providers delivering sexually transmitted infection (STI) services found that providers were uncomfortable discussing sexual issues with patients, and that patients preferred same-gender providers (34). This agrees with our finding that providers felt communication to be restricted with patients of the opposite gender, given that patients felt more comfortable discussing intimate health issues with someone they felt closer to socially and culturally. Our results indicate that medical advice is received differently depending on the gender of the patient-provider dyad, which is supported by findings that patient-doctor gender discordance impacts level of agreement on advice given during consultation (35). The same Kenyan study reported that health care providers also faced difficulties delivering STI services and condom advice due to traditional gender roles (34), which agrees with our findings describing conflicts between gender and professional roles.

Contextualizing the findings in this analysis is challenging given that all studies referenced with one exception are from other settings. There is a paucity of research exploring the impact of gender specifically on the patient-provider dynamic in this region despite the clear impact of gender inequities on the HIV epidemic in Kenya.

Interestingly, our findings indicated that providers viewed negatively and tended to expect females more than males to be non-adherent with lower retention rates due to gendered contextual barriers. However, most recent quantitative studies in this region have concluded that men exhibit lower linkage, retention (7, 8), and health service utilization rates (6), and providers in Kenya have reported men to be more fearful of services, preferring instead to visit private pharmacies (34). Men have also been characterized as more vulnerable to adherence issues (36, 37). Future studies should further explore this discrepancy given that gender appears to inaccurately bias provider perceptions of female patients (18, 38, 39), which significantly impact HIV treatment decisions (23, 24). Moreover, provider attitudes have been identified as a major barrier to HIV care in this region due to judgment and scolding of non-adherent patients (40). Biases against female patients due to underlying gender norms may lead to provider discrimination and alienation of female patients, thereby exacerbating existing, deeply-entrenched gender inequities. Given that the patient-provider relationship has been identified as a key factor in patient engagement and retention (18, 20, 22, 27, 41), it is a missed opportunity to mitigate the negative impacts of gender norms on HIV patient care-seeking behavior.

These findings have several important implications for research as well as the delivery of HIV care in this setting. Gender as a sociocultural determinant of health and adherence has been identified as a high-impact research priority in the Kenyan National AIDS Strategic Framework (42). However, a large emphasis is placed on targeting gender-based violence as an HIV prevention and control strategy with little focus on the myriad of other gender-related contextual barriers that contribute to poor engagement and adherence, and shape the patient-provider dynamic. There has been very little research exploring provider perspectives, and no studies applying gender analysis using provider qualitative interview data in this region. Moreover, studies collecting data to investigate the impact of gender norms on HIV care are often carried out by hospitals and universities, and are therefore not captured in the National Strategic Framework (42). A greater focus on enacting the gender-related research priorities identified in the National AIDS Strategic Framework and disseminating findings is key to future HIV prevention and control.

Furthermore, given the pivotal role providers play in shaping HIV care-seeking behaviors, a greater focus on leveraging this influence through a patient-centered approach may be effective toward mitigating gender-based contextual barriers for patients. Health care providers wield considerable power in the patient-provider relationship, especially in more paternalistic cultural contexts. Creating more opportunities for the training and supervision of providers in patient-centered care may improve both patient-provider relationships as well as HIV outcomes. Successful patient-centered care models focused on education and advanced training for providers, and support groups and self-care for patients, have been implemented in Uganda and South Africa to improve outcomes in patients with cardiovascular issues and TB/HIV co-infection (43, 44). Patient-centered models may help reduce gender-related challenges in the patient-provider relationship and consequently, gender-related barriers to HIV care.

This study had some limitations. Of note is the gender-skewed sample with only 16 male participants. Greater representation among male providers may have been informative for this gender analysis. However, given that health care delivery in western Kenya is largely dominated by women and nurses (45) the sample in this study is broadly representative of health care provider demographics in this region. Moreover, patient gender rather than provider gender has been identified as the main factor shaping provider attitudes and perceptions in other studies (18), though we did not specifically assess the interactions of provider gender in this analysis. Also, all interviewers were young women, which may have had an impact on provider responses given the issues related to gender dynamics in dyads highlighted in this study. Additionally, a rigorous process was carried out for codebook creation to ensure validity of the analysis.

Conclusion

This study explored the impact of culturally defined gender constructs on the patient-provider relationship. The interaction of provider and patient gender emerged as an important factor shaping the context in which patients seek and receive HIV care in this region, and for some dyads, negatively impacted provider perceptions, attitudes and communication. This can potentially alter care-seeking behaviors and contribute to suboptimal engagement and adherence. Given the important role filled by providers in shaping HIV care, further research should focus on the patient-provider relationship as an opportunity to mitigate gender-related contextual barriers and impact HIV care-seeking behaviors in western Kenya. Additionally, enhancing gender sensitivity in HIV care models as a strategy to train providers to perceive gender-related influences on patient behavior and communication may help them provide better care irrespective of these influences (46, 47).

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge the health care providers who participated in this study whose time and insights made this work possible. We would also like to thank the AMPATH clinical and administrative team, and the research assistants involved in data management for their dedication, commitment and skill.

Funding: This research was supported by a Career Development Award (K01MH099966) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and in part by a grant to the USAID-AMPATH Partnership from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) as part of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Reddy V ST, Rispel L, editor. From Social Silence to Social Science: Same-Sex Sexuality, HIV&AIDS and Gender in South Africa. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sa Z, Larsen U. Gender inequality increases women’s risk of hiv infection in Moshi, Tanzania. Journal of biosocial science. 2008;40(4):505–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malunguza N, Mushayabasa S, Chiyaka C, Mukandavire Z. Modelling the effects of condom use and antiretroviral therapy in controlling HIV/AIDS among heterosexuals, homosexuals and bisexuals. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine. 2010;11(3):201–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson ET, Collins SE, Kung T, Jones JH, Hoan Tram K, Boggiano VL, et al. Gender inequality and HIV transmission: a global analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17:19035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NASCOP. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012: Final Report. Nairobi, Kenya: National AIDS & STI Control Programme; June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiCarlo AL, Mantell JE, Remien RH, Zerbe A, Morris D, Pitt B, et al. ‘Men usually say that HIV testing is for women’: gender dynamics and perceptions of HIV testing in Lesotho. Culture, health & sexuality. 2014;16(8):867–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genberg BL, Naanyu V, Wachira J, Hogan JW, Sang E, Nyambura M, et al. Linkage to and engagement in HIV care in western Kenya: an observational study using population-based estimates from home-based counselling and testing. The lancet HIV. 2015;2(1):e20–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochieng-Ooko V, Ochieng D, Sidle JE, Holdsworth M, Wools-Kaloustian K, Siika AM, et al. Influence of gender on loss to follow-up in a large HIV treatment programme in western Kenya. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88(9):681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Sexuality and the limits of agency among South African teenage women: theorising femininities and their connections to HIV risk practices. Social science & medicine. 2012;74(11):1729–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider BES NE, editor. Women Resisting AIDS: Feminist Strategies of Empowerment 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waithera Don’t Sleep African Women: Powerlessness and HIV/AIDS Vulnerability Among Kenyan Women. Pittsburgh, PA: RoseDog Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jewkes R HIV/AIDS. Gender inequities must be addressed in HIV prevention. Science. 2010;329(5988):145–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-positivity in young, rural South African men. International journal of epidemiology. 2006;35(6):1455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Patient-doctor decision-making about treatment within the consultation--a critical analysis of models. Social science & medicine. 2006;62(1):116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowe K, Moodley K. Patients as consumers of health care in South Africa: the ethical and legal implications. BMC medical ethics. 2013;14:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackstock OJ, Beach MC, Korthuis PT, Cohn JA, Sharp VL, Moore RD, et al. HIV providers’ perceptions of and attitudes toward female versus male patients. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2012;26(10):582–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient gender and physician practice style. Journal of women’s health. 2007;16(6):859–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elderkin-Thompson V, Waitzkin H. Differences in clinical communication by gender. Journal of general internal medicine. 1999;14(2):112–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisman CS, Teitelbaum MA. Women and health care communication. Patient education and counseling. 1989;13(2):183–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aziz M, Smith KY. Treating women with HIV: is it different than treating men? Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2012;9(2):171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozzette SA, Berry SH, Duan N, Frankel MR, Leibowitz AA, Lefkowitz D, et al. The care of HIV-infected adults in the United States. HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study Consortium. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;339(26):1897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong MD, Cunningham WE, Shapiro MF, Andersen RM, Cleary PD, Duan N, et al. Disparities in HIV treatment and physician attitudes about delaying protease inhibitors for nonadherent patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004;19(4):366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apollo A, Golub SA, Wainberg ML, Indyk D. Patient-provider relationships, HIV, and adherence: requisites for a partnership. Social work in health care. 2006;42(3–4):209–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21(6):661–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS medicine. 2006;3(11):e438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health education quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun VaC V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient education and counseling. 2009;76(3):356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jefferson L, Bloor K, Birks Y, Hewitt C, Bland M. Effect of physicians’ gender on communication and consultation length: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of health services research & policy. 2013;18(4):242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmittdiel JA, Traylor A, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Ferrara A, Subramanian U. The association of patient-physician gender concordance with cardiovascular disease risk factor control and treatment in diabetes. Journal of women’s health. 2009;18(12):2065–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chesang K, Hornston S, Muhenje O, Saliku T, Mirjahangir J, Viitanen A, et al. Healthcare provider perspectives on managing sexually transmitted infections in HIV care settings in Kenya: A qualitative thematic analysis. PLoS medicine. 2017;14(12):e1002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schieber AC, Delpierre C, Lepage B, Afrite A, Pascal J, Cases C, et al. Do gender differences affect the doctor-patient interaction during consultations in general practice? Results from the INTERMEDE study. Family practice. 2014;31(6):706–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulle C, Kouanfack C, Laborde-Balen G, Boyer S, Aghokeng AF, Carrieri MP, et al. Gender Differences in Adherence and Response to Antiretroviral Treatment in the Stratall Trial in Rural District Hospitals in Cameroon. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2015;69(3):355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braitstein P, Boulle A, Nash D, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Laurent C, et al. Gender and the use of antiretroviral treatment in resource-constrained settings: findings from a multicenter collaboration. Journal of women’s health. 2008;17(1):47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein B, Kane R. Physicians’ attitudes toward female patients. Medical care. 1981;19(6):600–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall JA, Epstein AM, DeCiantis ML, McNeil BJ. Physicians’ liking for their patients: more evidence for the role of affect in medical care. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1993;12(2):140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ransom J, Johnson AF. Key findings: a qualitative assessment of provider and patient perceptions of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Social work in public health. 2009;24(1–2):47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1998;74(6):1464–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.UNAIDS. Kenya AIDS Response Progress Report 2014: Progress Towards Zero. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Longenecker CT, Kalra A, Okello E, Lwabi P, Omagino JO, Kityo C, et al. A Human-Centered Approach to CV Care: Infrastructure Development in Uganda. Glob Heart. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zelnick JR, Seepamore B, Daftary A, Amico KR, Bhengu X, Friedland G, et al. Training social workers to enhance patient-centered care for drug-resistant TB-HIV in South Africa. Public Health Action. 2018;8(1):25–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wakaba M, Mbindyo P, Ochieng J, Kiriinya R, Todd J, Waudo A, et al. The public sector nursing workforce in Kenya: a county-level analysis. Human resources for health. 2014;12:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Celik H, Lagro-Janssen TA, Widdershoven GG, Abma TA. Bringing gender sensitivity into healthcare practice: a systematic review. Patient education and counseling. 2011;84(2):143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sen G ÖP. Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network. Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Ineffiicient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Final Report to the WHO Commussion on Social Determinants of Health. 2007. [Google Scholar]