Abstract

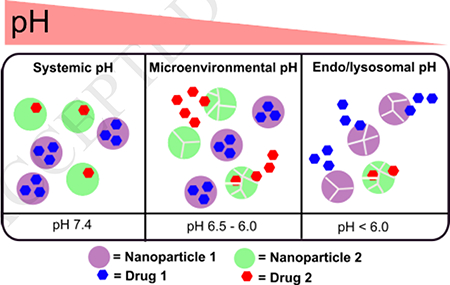

A pH-responsive nanoparticle platform, based on PEG-b-poly (carbonate) block copolymers have been proposed that can respond to low pH as found in many cancer micro- and intracellular environment, including that in pancreatic cancer. The hydrophobic domain, i.e., the poly (carbonate) segment has been substituted with tertiary amine side chains, such as N, N′-dibutylethylenediamine (pKa = 4.0, DB) and 2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-ethyl-amine (pka = 5.4, Py) to generate two different sets of block copolymers namely PEG-DB and PEG-PY systems. These side-chain appended amines promote disassembly of nanoparticles and activation of drug release in response to pH conditions mimicking extra- (pH 6.9–6.5) and intracellular compartments (5.5–4.5, from early endosome to lysosome) of cancer tissues respectively. A frontline chemotherapy used for pancreatic cancer, i.e., gemcitabine (GEM) and a Hedgehog inhibitor (GDC 0449) has been used as the model combination to evaluate the encapsulation and pH-dependent release efficiency of these block copolymers. We found that, depending on the tertiary amine side chains appended to the polycarbonate segment, these block copolymers self-assemble to form nanoparticles with the size range of 100–150 nm (with a critical association concentration value in the order of 10−6 M). We also demonstrated an approach where GEM and GDC 0449-encapsulated PEG-DB and PEG-PY nanoparticles, responsive to two different pH conditions, when mixed at a 1:1 volume ratio, yielded a pH-dependent co-release of the encapsulated contents. We envision that such release behaviour can be exploited to gain spatiotemporal control over drug accumulation in pathological compartments with different pH status. The mixture of pH-responsive nanoparticles was found to suppress pancreatic cancer cell proliferation when loaded with anticancer agents in vitro. Cell-proliferation assay showed that both variants of PEG-b-polycarbonate block copolymers were inherently non-toxic. We have also immobilized iRGD peptide on intracellularly activable PEG-DB systems to augment cellular uptake. These targeted nanoparticles were found to promote selective internalization of particles in pancreatic cancer cells and tumor tissue.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Colloids, Block copolymers, pH-responsive nanocarriers, Drug Delivery, Pancreatic Cancer

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

A large cohort of clinical conditions, ranging from inflammation to cancer, precipitates in pH-differentials existing across different pathophysiological compartments of the disease-microenvironment [1–3]. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) for example, is one of such diseases and is the most virulent forms of all cancers which shows a prominent gradient of decreasing pH from extracellular to intracellular compartments [4]. Clinical success of PDAC critically hinges on addressing a set of mutually connected, yet compartmentalized, pathology that includes mature and differentiated cancer cells in an acidified (as low as pH 6.0–6.5, for pancreatic cancer), desmoplasia-protected microenvironment. While desmoplasia impairs the delivery of drugs to malignant cells of this disease, tumor-stroma interaction of paracrine or autocrine origin, create a complicated signaling network in PDAC that drives tumor progression and prognosis [5, 6]. Hence, combination therapy, such as gemcitabine (GEM, an antimetabolite, active in the nucleus) and a variety of receptors inhibitors has been proposed for PDAC, which halts the cross-talk between cancer cells and cancer fibroblast (stromal cells) [7]. Although GEM is a water-soluble compound, non-specific toxicity and acute hydrophobicity of the adjuvant (such as GDC 0449) often render such combinations challenging for clinical applications. Drug accumulation in specific micro-environmental and intracellular compartments at maximum therapeutic and sub-toxic concentration is also an unmet challenge for this combination delivered using conventional dosage forms[8]. In addition, a high volume of distribution (Vd), fast metabolic clearance rate, frequent dosage administration regimen, drug-associated side effects, and tumor heterogeneity severely reduce the therapeutic gain of the individual drug in the pancreatic cancer setting[9].

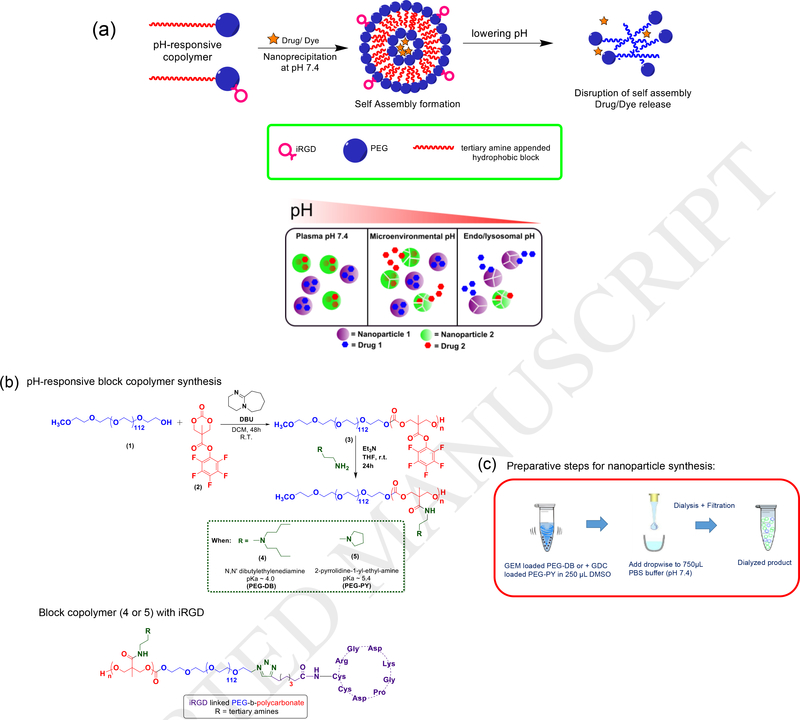

Drug delivery methods using nanoparticles have been a well-established approach to improve drug efficacy, enhanced circulation lifetime, and tolerability[10]. While the nanocarrier-assisted drug delivery provides an option to target diseased tissues using small molecular ligands and peptides, extensive investigation has also been conducted designing carrier systems that respond to cancer microenvironment-specific cues such as pH [11–14], hypoxia [15–18], enzyme over-expression [4, 19], angiogenesis, [20] and signaling pathways regulating apoptosis [21]. Since there is a sharp pH-gradient between stromal to intracellular regions within PDAC microenvironment [22], we hypothesize that a set of nanoparticles composed of amine-rich block copolymers of varying pKa will be an effective platform to deliver a combination of drugs, where one of the agents could be highly hydrophobic, in a pH-specific pattern. Such condition-specific delivery will be critical to interfere with the growth of and metabolic interactions between cancer cells that drive PDAC growth. The general concept of such spatio-selective activation and synthetic route of such nanoparticle-forming block copolymers is presented in Figure 1a-b.

Figure 1.

a. Top panel: Self-assembly of pH responsive polymers (top panel) and mixed nanoparticle platform for pH-selective drug release (bottom panel). (b) Synthetic route to pH-responsive PEG-b-poly (carbonate) copolymer and their iRGD conjugated variant. (c) Preparative steps for nanoparticle formulation by nanoprecipitation method.

An extensive systematic investigation from Hammond et al. has already established the pH-responsive block copolymers of PEG-b-poly (peptide) with tertiary amines as pH-responsive triggers to be an excellent platform for intracellular compartment-specific delivery of cytotoxic agents such as doxorubicin for triple negative breast cancer and ovarian cancer[23–25]. Kataoka[26] et al. and Lecommandoux [27] et al. have shown the efficacy of block copolymers to encapsulate and release both hydrophilic and hydrophobic class of drugs to prostate, breast, and liver cancer cells, and the diversity of tertiary amines as pH-responsive triggers. Mahato [28] et al. recently shown that PEG-b-polycarbonate block copolymer micelles containing conjugated and encapsulated synergistic combination showed enhanced performance in slowing PDAC progression in mice model. Since the appearance of the first report by Hedrick’s[29] et al. on PEG-b-poly (carbonate) block copolymer derived from cesium fluoride mediated ring-opening polymerization of pentafluorophenol protected bis (methyl propionic acid), the use and modification of such approach by other groups for drug delivery applications have been reported by Chilkoti et al [30]. Gao et al. have synthesized pH-activable micellar nanoparticles composed of ionizable block copolymers where ionization the of tertiary amines appended to the hydrophobic block resulted in pH-dependent fluorescent readout [31–33]. We envisioned that combining and harnessing the enhanced hydrophobic interactions of the polycarbonate domains of PEG-b-poly (carbonate) block copolymers and pH-specific protonation capacity of tertiary amines to generate a systematically stable, spatiotemporally controlled drug nanocarrier can induce enhanced and targeted accumulation of therapeutic agents to PDAC microenvironment. [6] [33, 34] [1]. To establish the proof-of-concept, we have used a combination of GEM and GDC 0449 (a transmembrane SMO protein inhibitor), which has been proposed to suppress the autocrine and paracrine signalling between cancer cells and stromal cells. Our working hypothesis was that, if we encapsulate GDC-0449 and GEM within PEG-PY and PEG-DB polymersomes and mix these two types of nanoparticles at different stoichiometric ratio, we will obtain spatially controlled release of both the drugs, where the kinetics of release of the individual drug will depend on the mixing ratio of the respective nanoparticles. We also hypothesize that these payloads will be co-released as a function of pH as the nanoparticle population progresses from pH mimicking desmoplastic, acidified micro-environment (pH 6.9 – 6.5) [35–37] to intracellular pH of acidic compartments such as endosomal-lysosomal pathways (pH 5.5 – 4.5). We have selected pancreatic cancer to demonstrate the therapeutic efficacy of the proposed system because overexpression of Sonic type Hedgehog receptors is observed in both pre-invasive and invasive epithelium of 70% of human pancreatic cancers, and is absent in normal pancreas irrespective of the progression stage of the disease [38]. In addition, aberrant Hedgehog ligand expression has been found to have a direct association with oncogenic KRAS mutation, which is found in > 95% cases of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC) [39]. Hence, in this report we report the synthesis and fabrication of a set of pH-responsive nanoparticle constructs that are designed to respond to such dynamically changing pH-environment of PDAC where Hedgehog inhibition is necessary, assess their physicochemical and pH-responsive properties, estimate encapsulation and release of combination agents in response to varying pH, and evaluate interactions with pancreatic cancer cells in in vitro and in vivo model.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and anhydrous solvents from VWR, EMD Millipore. 1H NMR Spectra were recorded using a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer using TMS as the internal standard. IR Spectra were recorded using an ATR diamond tip on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 8700 FTIR instrument. Gel permeation chromatographic measurements were done on a GPC system (EcoSEC HLC-8320GPC, Tosoh Bioscience, Japan) using a differential RI detector, employing polystyrene (Agilent EasiVial PS-H 4ml) as the standard and THF as the eluent with a flow rate of 0.35 mL per minute at 40 °C. The sample concentration used was 1 mg/mL of which 20 μL was injected. DLS measurements were carried out using a Malvern instrument (Malvern ZS 90). UV-Visible and fluorescence spectra were recorded using a Varian UV-Vis spectrophotometer and a Fluoro-Log3 fluorescence spectrophotometer respectively. TEM studies were carried out using a JEOL JEM-2100 LaB6 transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Peabody, Massachusetts) with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV.

Synthesis of polymers.

PEG-b-poly (carbonates) were synthesized using a macroinitiator, such as poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG, Mn = 5,000 g/mol) (1) through a ring opening polymerization of pentafluorophenol protected bis (methoxy propionic acid) derivative 2, according to the synthetic procedures described by Hendricks et al, and later modified by Chilkoti [30] (Figure 1). The resulting macromolecular intermediate 3 was post-functionalized [40] stoichiometrically using two different amines, namely N, N′dibutylethylenediamine (pKa = 4.0), and 2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-ethyl-amine (pka = 5.4) to synthesize the pH-responsive block copolymers namely PEG-DB (4) [PEG-b-poly(carbonate) appended with N, N′dibutylethylenediamine side chains] and PEG-PY (5) [i.e. PEG-b-poly(carbonate) appended with 2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-ethylamine side chains] respectively. 1H NMR and IR spectroscopy have been carried out to characterize resulting block copolymers and their precursors (Figure S1-S5, supporting information). Both 4 and 5 were water soluble at room temperature.

pKa Determination.

Acid dissociation constant, i.e., pKa values of both copolymers were determined by titrating the aqueous solution of these polymers against 0.1 N sodium hydroxide, and the corresponding monomers were also titrated using the same method. The pKa was calculated by measuring the pH at the half-equivalence (inflection) point of the titration curve.

Determination of the Critical aggregation constant (CAC) of the polymers.

From a stock solution of 0.1 mM pyrene in dichloromethane, 10 μL aliquot was taken in different vials, and the dichloromethane was allowed to dry. To each of these vials, various measured amounts of two different amines substituted polymers was added (stock solution concentration 1 mM) so that the concentrations varied from 0.0019 mM to 0.5 mM and the final concentration of pyrene in each vial was 1 μM. The vials were sonicated for 45 minutes and then allowed to stand for 3 hours before recording the fluorescence spectra [41]. The fluorescence emission spectra were recorded at an excitation wavelength of 337 nm with a bandwidth of 2.5 nm (for both excitation and emission). The ratio of the intensities at 373 nm and 384 nm were plotted against the concentration of the polymer, and the inflection point of the curve was used to determine the CAC.

Preparation of Nanoparticles.

To construct the self-assembled structures of amphiphilic block copolymers PEG-DB (4) and PEG-PY (5) in the form of nanoparticles, the nanoprecipitation method from a selective solvent (DMSO) to a non-selective solvent (buffer) was employed. To form nanoparticles, 10 mg of PEG-DB (4) or PEG-PY (5) block copolymers were dissolved in 250 μL of DMSO, and the solution was added drop-wise to 750 μL of PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The resultant solution was transferred to a float-a-lyzer (MWCO 3.5–5 kDa) and allowed to dialyze against ~ 700 mL PBS buffer (pH 7.4) overnight with constant shaking at moderate speed. The solutions were then filtered using a 0.2 μm PES filter and the size measured using DLS (Dynamic Light Scattering) studies at a scattering angle of 90°.

Formation of targeted nanoparticles: Synthesis of iRGD containing (4) and (5).

To synthesize the peptide containing polymersomes, iRGD hexanoic acid was “clicked” with azide-(4) and azide-(5) separately. Briefly, azide-containing 4 and 5 and the peptide were separately dissolved in deionized water (5 mg/mL, for the peptide, using sonication in iced water). For 5 mg of polymer 16 μL of Cu-ascorbate complex and 16 μL of the sodium ascorbate (27 mg/mL in deionized water) was added and the reaction was allowed to stir at room temperature for 24 hours. Following the reaction, the contents were moved to a dialysis bag (MWCO 1000 Da) and dialyzed for 72 hours with a media change every 24 hours. The contents of the dialysis bag were subsequently lyophilized and analyzed. A 1-mg/mL aqueous solution of the freeze-dried product and the polymer prior to conjugation with the peptide were analyzed using CD spectroscopy.

Encapsulation and Release of Carboxyfluorescein from pH-responsive nanoparticles.

Following the protocol described by Mallik et al.[18], 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (CF) encapsulation was carried out by preparing a stock solution of 1 mM carboxyfluorescein in PBS buffer (137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and adding 250 μL of the polymers (10 mg/ mL) to 2 mL of the dye solution in a drop-wise pattern with constant stirring. The resulting solution was allowed to stir for an hour followed by sonication for 60 minutes and dialyzed overnight using a float-a-lyzer (MWCO 3.5–5 k Da) against 700 mL PBS buffer. The media was changed completely to maintain sink condition, and dialysis was continued for another 6 hours until no further discoloration of the media was observed. The release of carboxyfluorescein from polymersomes was studied at different pH (4.5 and 7.4 for PEG-DB polymersomes and pH 5.5 and pH 7.4 for PEG-PY polymersomes) by measuring the fluorescence emission intensity by exciting the respective release solutions at 492 nm and recording the emission intensities at 515 nm (supporting information, Figure S7). After 5 hours, 20 μL of Triton was added to disintegrate the polymersomes and the fluorescence emission intensity measured for total release after disintegration. Percentage release was calculated using the formula, and the cumulative percentage release was plotted against time:

Encapsulation of drug(s) and dye in block copolymeric nanoparticles:

For preparation of drug loaded copolymeric nanoparticles, 10 mg of the respective block copolymer were dissolved in 250 μL of DMSO in the presence of 5 mg of drugs (either GEM or GDC). The solution was added dropwise to a stirring solution of 750 μL of PBS buffer. The solution was allowed to stir for overnight followed by centrifugation using micro-centrifuge filters at 500 rpm. The filtrate was analyzed using UV-Vis spectroscopy for quantification of the amount of drug loaded within nanoparticles. For dye (such as Alexa Fluor 647 encapsulation, 10 mg of the polymer and 50 μL of the dye were dissolved in 250 μL of DMSO. The solution was added to a 750 μL solution of PBS under vigorous stirring in a dropwise pattern. The solution was stirred for an hour, and dialyzed using a float-a-lyzer of MWCO of 3.5–5 kDa against 800 mL of buffer.

In vitro drug release experiments.

Drug release experiment was conducted by taking 1 mL of the drug-loaded nanoparticle solution in a float-a-lyzer (MWCO 3.5–5 kDa). Nanoparticle solution was composed of GEM loaded PEG-DB, and GDC loaded PEG-PY polymersomes mixed at 1:1, 1:4, and 4:1 ratio respectively. The respective solution was immersed in 5 mL of buffer maintained at a desired pH. A specified volume of the bulk solution was withdrawn periodically and replaced by equal volume of fresh buffer of similar pH to maintain the sink condition. Dye release experiment was conducted analogously for a fixed ratio.

In vitro cell culture.

The pancreatic cancer cell line, BxPC-3 and Mia PaCa-2 were from American Type Culture Collection and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2. The BxPC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI media (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning). MiaPaCa-2 cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2.5% horse serum (Corning). The cell lines were sub-cultured by enzymatic digestion with 0.25% trypsin/ 1 mM EDTA solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) when they reached approximately 70% confluency.

Cell viability assay.

Cytotoxicity of PEG-DB and PEG-PY either as unassembled block copolymers or encapsulated with GEM and GDC 0449 were tested on both BxPC-3 and MiaPaCa-2 cells. For BxPC-3 cells, 5000 cells/well were plated. After 24h, the cells were treated with 0.8 μM of GEM encapsulated PEG-PY and 1.5 μM GDC encapsulated PEG-DB nanoparticles. For MiaPaCa-2, 1000 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and 24 h later, were treated with different concentration of PEG-DB, PEG-PY block copolymers or drug-encapsulated nanoparticles from at different concentrations. For this cell line, the concentration of free or nanoparticle encapsulated GDC was kept constant at 10 nM, and the concentration of GEM (free or encapsulated) were varied from 0 – 100 nM. After 72 h incubation, cell viability assay was performed by MTS assay.

Cellular uptake studies.

MiaPaCa-2 cells were plated in 6-well plates at 5,000 cells/well and were allowed to grow to 70% confluence. The cells were then incubated overnight with either targeted or non-targeted fluorescently (Alexa Fluor 647) labeled nanoparticles (at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL) at 37 °C. After the incubation period, the cells were washed with cold PBS (3X), trypsinized, and resuspended in PBS. Propidium iodide (PI) staining was used to identify the live and the dead cell population. Subsequently, the cells were suspended in a flow cytometry buffer (PBS with 0.1% BSA), and the cell-associated fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 647 was determined by BD Biosciences Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer. Three technical replicates were included for each experiment, and the experiments were performed in biological triplicates.

Confocal microscopy.

Cellular uptake of nanoparticles constituted from PEG-b-poly (carbonate) block copolymers was assessed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The confocal images were taken using Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 microscope equipped with LSM700 laser scanning module (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), at 40X magnification with 40×/1.3 Plan-Apochromat lens. MiaPaCa-2 cells were seeded in ibidi® glass bottom dish (35 mm) at 1 × 105 cells per well and grown overnight. Then, cells were incubated with polymersome at 37 °C in DMEM high glucose medium for 24 h. At the end of this period, cells were washed with PBS and followed by addition of Opti-MEM and imaging.

In vivo experiments.

Xenografts were established by injecting 0.1 mL of 8 × 107 BxPC-3 Cells without Matrigel® basement membrane matrix on the hind flank of six- to eight week old athymic nude mice (Nu/Nu). Before establishing the xenograft, the mice were maintained in sterile conditions using the Innovive IVC system (Innovive), following a protocol approved by North Dakota State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. An acclimatization period of 1 week has been allowed before experimental manipulation. Tumors were allowed to form for 3 weeks. Fluorescently-tagged nanocarrier suspension (100 μL, 10 mg/mL equivalent concentration of PEG-DB containing 5% iRGD-bound PEG-DB) were injected via the tail vein, and the tumors were harvested after 24h and processed by Advanced Imaging and Microscopy Laboratory at NDSU. Briefly, tumor tissues from control and nanoparticle-treated mice were collected and fixed for 24h in formaldehyde. Paraffin-embedded 5 μm thick sections of tumor tissues were deparaffinized with Histo-Clear and ethanol, followed by antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) using an autoclave method. The sections were blocked for 20 minutes using blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum in TBST) and incubated with S100 (Abcam, UK) primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature followed by FITC-labeled secondary antibody (Biotium, Fremont, CA). After mounting a coverslip using Hardset Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), slides were visualized using a Zeiss AxioObserver Z1 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Self-assembly and aggregation properties of pH-responsive block copolymers.

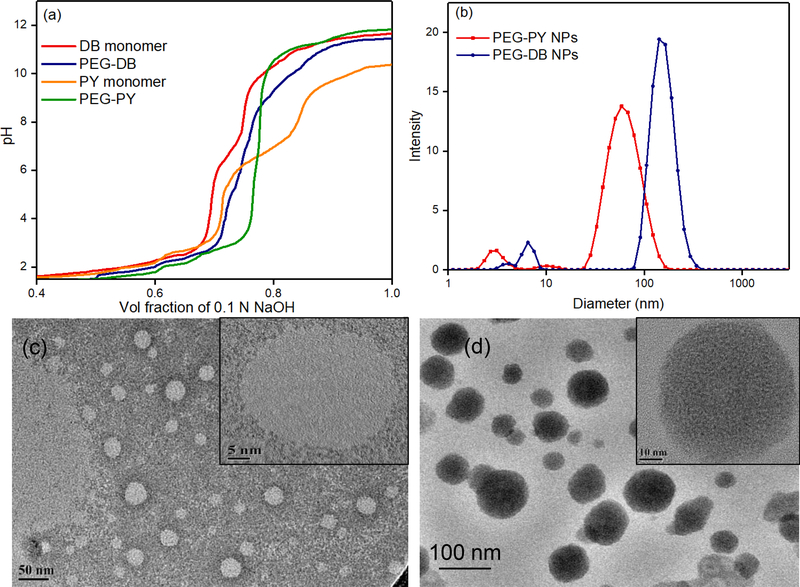

Block copolymers form a stable nanoparticle assembly as micelles or polymersomes where hydrophobic and hydrophilic blocks assist the formation of such structures [10, 33, 42]. These nanoparticles can encapsulate a wide variety of small molecular weight compounds such as drugs and dyes [27]. We synthesized PEG-b-poly (carbonates) block copolymers and used two different tertiary amine groups attached to the hydrophobic blocks to regulate their pKa values. In addition, we have also immobilized the iRGD peptide (a cyclic oligopeptide that can recognize neuropilin and integrin receptors) onto the PEG block of these copolymers to augment cellular uptake. The synthetic scheme of the block copolymers is presented in Figure 1b. First, we determined the pKa values of the block architectures and compared with that of the corresponding monomers. Figure 2a shows the titration curves of 4 and 5, indicating the net pKa values were at 5.53 ± 0.14 and 6.83 ± 0.23 (n = 2) respectively. The pKa was estimated by measuring the pH at the half-equivalence (inflection) point of the titration curve. These values indicated that, at these mildly acidic pHs, at least 50% of PEG-DB and PEG-PY block copolymers would remain in ionized (protonated) form facilitating the amphiphilic to hydrophilic transition, which will result in destabilization of their self-assembled structures that would otherwise be stable at plasma pH of 7.4. Hence, the destabilization pH of these copolymeric block self-assemblies can be harnessed to initiate drug release at desmoplastic and intracellular pH. PEG-PY nanoparticles, composed of the block copolymer (5) were found to have an average hydrodynamic diameter in the range of 117 ± 9.8 nm, while PEG-DB derived nanoparticles (constructed from block copolymer 4) showed an average diameter of 149 ± 14.4 nm (Figure 2b). TEM studies also showed the presence of spherical particles although a fraction of smaller particles (Figure 2c-d) was observed which also correlates with dynamic light scattering data as shown in Figure 2b [43]. The difference between the sizes of PEG-PY and PEG-DB nanoparticles can be attributed to the molecular structures of the side chains appended to the hydrophobic blocks of the nanoparticle-forming block copolymers. While PEG-PY block copolymers are appended with a strained cyclobutyl amine side chain at their hydrophobic polycarbonate block, PEG-DB systems contain the aliphatic n-butyl amines at the similar domain, likely resulting in nanoparticles larger in size than their PEG-PY counterpart. Following Eisenberg’s [42, 44] earlier work, since the ratio of the mass of the hydrophobic block to the total polymer mass (known as the f value) for both 4 and 5 lies typically between 0.35 and 0.45, the resulting PE-PY and PEG-DB nanoparticles are most likely to have polymersome-like architectures. However, in TEM image we did not observe any bilayer structure, rather a solid colloidal nanoparticles were found with an average diameter of 50–80 nm, most likely due to shrinkage of the nanoparticles upon drying (Figure 2c-d and Supporting information, Figure S6. Immobilization of the iRGD peptide onto nanoparticle surface was not found to alter the particle size or distribution significantly (Supporting information, Figure S7).

Figure 2.

(a) pH titration curves of the block copolymers and their corresponding monomers (b) Size distribution of nanoparticles by DLS (c) TEM of PEG-PY (5) NPs and HRTEM of a single nanoparticle (inset) (d) TEM image of PEG-DB (4) NPs and HRTEM of a single PEG-DB nanoparticle (inset).

Determination of Critical Association Concentration (CAC) of block copolymers.

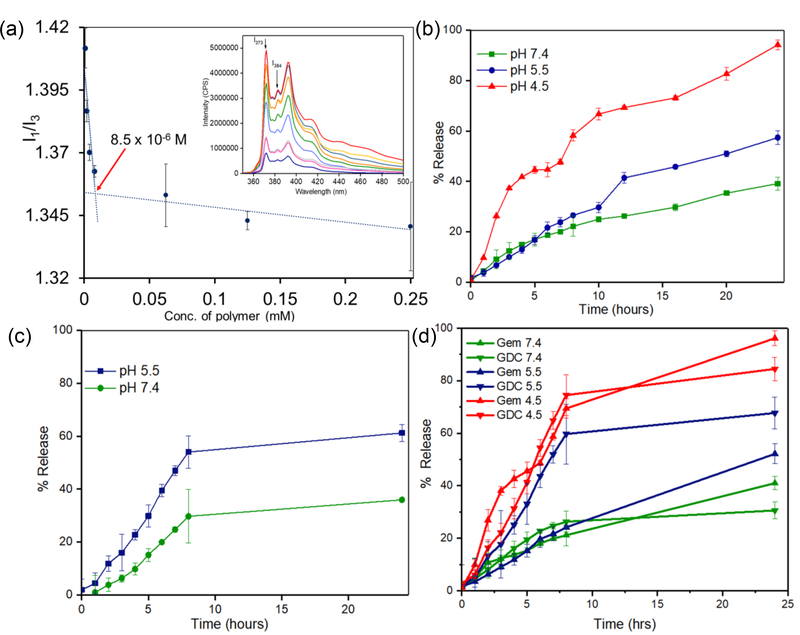

The aggregation properties of the block copolymer 4 and 5 were then evaluated at pH 7.4 using pyrene as the probe [41]. It has been reported that the first (λ373 nm) and third (λ384 nm) peaks in the fluorescence emission spectra of pyrene are sensitive to the polarity of the environment and, the ratio of these two signals can be used to determine the stability of association of block copolymers as micelles or polymersomes [45]. We observed that the ratio of I373/I384 gradually decreased as the polymer concentration was increased up to a concentration of 8.5 μM for 4 (Figure 3a) and 20 μM for 5 (supporting information, Figure S8), after which the I373/I384 ratio remained mostly unchanged. The value of I1/I3 at the breakpoint (1.35, Figure 3a for 4) leads to the inference that the probe is located in a hydrophobic environment created by the aggregation of the hydrophobic segments beyond the critical association concentration of the respective block copolymers. The critical aggregation concentration (CAC) values obtained for 4, and 5 were in the order of 8.5 × 10−6 and 2.0 × 10−5 M respectively and found to be comparable to polyesters and polypeptide-derived block copolymers[46]. The CAC value for copolymer 5 is presented in Supporting information, Figure S8b. Lower CAC values with 4 can be attributed to butyl chains of the tertiary amine which likely to form stronger hydrophobic entanglement than their cycloaliphatic counterpart 5. This experiment established that both 4 and 5 lead to the formation of PEG-DB and PEG-PY nanoparticles, which are sufficiently stable at pH 7.4 usable for systemic administration.

Figure 3.

(a) Plot of I1/I3 of 10−6 M of pyrene encapsulated in varying concentrations of PEG-DB (4). Fluorescence emission spectra of PEG-DB (λex = 337 nm) are shown in the inset and corresponding error bars represent standard deviations n = 3. (b) Cumulative percent release of Gemcitabine from PEG-DB polymersomes at pH 4.5, 5.5, and 7.4 (c) Corresponding release profile for GDC 0449 encapsulated in PEG-PY polymersomes at pH 5.5 and pH 7.4 Error bars represent standard deviations when n = 3. (d) Cumulative percentage release of GEM and GDC from 1:1 v/v mixture of drug-encapsulated PEG-DB and PEG-PY nanoparticles at different pH environment. Error bars represent standard deviation of the average of three measurements (n = 3).

pH-dependent Disassembly and content release from nanoparticles.

This is to note that, GEM (log P = −1.4), is a frontline chemotherapeutic agent for pancreatic cancer, which inhibits DNA repair and replication[47], while GDC 0449 (vismodegib, log P = 2.7) is a potent systemic inhibitor of Hh signal transduction [48] mediated by inhibition of transmembrane SMO proteins.[49] Both the drugs presented widely different lipophilicities to encapsulate in a conventional polymeric, such as poly (lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) or lipid-based nanoparticles. To establish the mechanistic stability and the pH-responsive properties of nanoparticles at microenvironmental and intracellular pH-range, we first encapsulated a self-quenching hydrophobic dye 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (CF) within PEG-DB and PEG-PY nanoparticles. We investigated the kinetics of the released CF as a function of time by measuring its fluorescence intensity in aqueous media [18]. For CF encapsulated in PEG-DB nanoparticles, the release was studied at both pH 4.5 and 7.4, while pH 5.5 and 7.4 were selected for investigating the release profile of CF from PEG-PY systems (supporting information, Figure S9). It was observed that, for PEG-DB systems, almost 100% of the dye was released by 7 hours at pH 4.5 (mimicking late-endosomal/lysosomal pH) while only 5% release at pH 7.4 (supporting information, Figure S9a). In case of PEG-PY NPs, about 80% of CF was released at pH 5.5 (mimicking PDAC microenvironmental pH) the end of 5 hours compared to 18% of content that released over the same timeframe at pH 7.4 (supporting information, Figure S9b). This indicates the stability of the polymersomes at pH 7.4 and their eventual protonation and destabilization of the self-assembled structures promoting compartment-specific, pH-dependent drug release. Following the release behavior of carboxyfluorescein, we set out to encapsulate GEM within PEG-DB nanoparticles, and GDC 0449 within PEG-PY systems. For PEG-DB nanoparticles, encapsulation efficiency of GEM was found to be 86 ± 3.18%, and the loading content was calculated as 29 ± 7.5 %, using the equation as described in the supporting information (for n = 5 separate analysis). The high loading content and efficiency of GEM is most likely attributed to the multiple dibutylamine groups in the hydrophobic block of the copolymer. On the other hand, for PEG-PY system, the loading content and efficiency for GDC was found to be 13 ± 2.9% and 26 ± 3.5%, respectively (n=5 separate analysis). The release of the encapsulated drugs from nanoparticles was monitored for 24 hours at regular intervals in different pH conditions (Figure 3b-c). While for PEG-DB nanoparticles, the cumulative percentage release of gemcitabine was found to be about 100% at the end of 24 hours at pH 4.5, only 38% release was observed at pH 7.4 (Figure 3b). When tested at pH 5.5, the extent of cumulative release of the drug was greater than that from pH 7.4 but substantially lower than that in pH 4.5 (Figure 3b). On the other hand for GDC 0449 encapsulated PEG-PY nanoparticles, ~62% and 35% of GDC 0449 was released at pH 5.5 and pH 7.4 respectively at the end of 24 hours (Figure 3c). The differential release of GEM at pH 4.5 and 5.5 from PEG-DB systems indicate the capacity of these nanoparticles to ensure maximum concentration of GEM to be released intracellularly rather in extracellular space. On the other hand, PEG-PY systems will trigger most of the payload release at the microenvironment mimicking pH of 5.5 thus promoting accumulation of the drug in the extracellular space. Although at current degree of functionalization of the pH-responsive side chains, we do observe ~35% of drug release at pH 7.4, most likely by optimizing the length of the hydrophobic block and PEG molecular weight, such non-specific release of GDC 0449 could be suppressed. This is to note that, release experiment for GDC loaded PEG-PY system was conducted only at pH 5.5 and not in lower pH conditions, as the release of this agent is expected to happen in extracellular compartments.

To evaluate the extent of release for GEM and GDC as a function of pH and time from mixed nanoparticle platform, we have incubated a 1:1 mixture (v/v) of PEG-DB (containing GEM) and PEG-PY (containing GDC) nanoparticle in a buffered solution of pH 7.4, 5.5 and 4.5 (Figure 3d). We observed that, at pH 7.4, the release of GEM and GDC were below 40% of the encapsulated dose over 24h. At lower pH of 5.5, GEM release was significantly sustained from PEG-DB nanoparticles than that of GDC from PEG-PY particles (52% of encapsulated GDC was released after 8 hours, compared to 20% of GEM released over the same period, Figure 3d). Further lowering of pH to 4.5, did not enhance the release of GDC significantly from PEG-PY system, but led to an approximately 3-fold increase of GEM release from PEG-DB system. Complete protonation of PEG-DB at pH 4.5 and partial protonation of the same at pH 5.5 is most likely to be the governing factor for such differential release in case of GEM from PEG-DB block copolymer assemblies. To provide the proof-of-concept of how the gradual decrease of pH from the blood to the endosomal-lysosomal compartment would affect the release of encapsulated materials from synthesized nanoparticles, we investigated the release of a model dye, Alexa Fluor 647 encapsulated within PEG-DB nanoparticles in gradually changing pH conditions (Figure S10, supporting information). First, the nanoparticle solution was incubated in pH 7.4, and the pH of the release medium was gradually reduced after every 3 hours by the addition of 0.1 N HCl. We observed that less than 10% of the encapsulated dye was released at pH 7.4 for the first 3 h from PEG-DB nanoparticles. At pH 5.5, which mimics the pH of extracellular space, approximately 2-fold enhancement of cumulative release of the dye from PEG-DB nanoparticles. Finally, when the pH was further lowered to intracellular pH (mimicking late endosomal-lysosomal pH), the release of Alexa Fluor 647 from the nanoparticle system was significantly enhanced after a period of 6 hours (Figure 3d) indicating the an almost quantitative release of the encapsulated content from PEG-DB block copolymeric nanoparticles at low pH. After investigating the release kinetics of individual drugs from respective nanoparticles mixed at 1:1 ratio, we set out to investigate the effect of pH-mediated release when the mixture has a different ratio of nanoparticles other than 1:1. It is interesting to note that, when we changed the ratio of the two nanoparticles from 1:1 of to 1:4 or 4:1 (PEG-DB: PEG-PY nanoparticles respectively), we did not observe any significant change of release at pH 7.4. This observation indicates that the nanoparticles will remain intact in systemic circulation independent of mixing ratio (Figure S11, supporting information). At pH 4.5, we observed the faster release of GEM after 8 h, likely due to increased protonation of GEM overcompensating the effect of mixing-ratio of nanoparticles. More prominent effect of mixing ratio was observed at pH 5.5 (blue lines, Figure S11, supporting information), where the difference of release between the two drugs after 8 hours was reduced by 2 (for 4:1 of PEG-DB to PEG-PY) to 8-fold (for 1:4 of PEG-DB to PEG-PY) than that obtained when the nanoparticle population was mixed at 1:1 ratio. This experiment indicates that for a nanoparticle-delivered combination therapy, it is be possible to change kinetics and availability of individual drug at a particular target by altering the ratio of the nanoparticles.

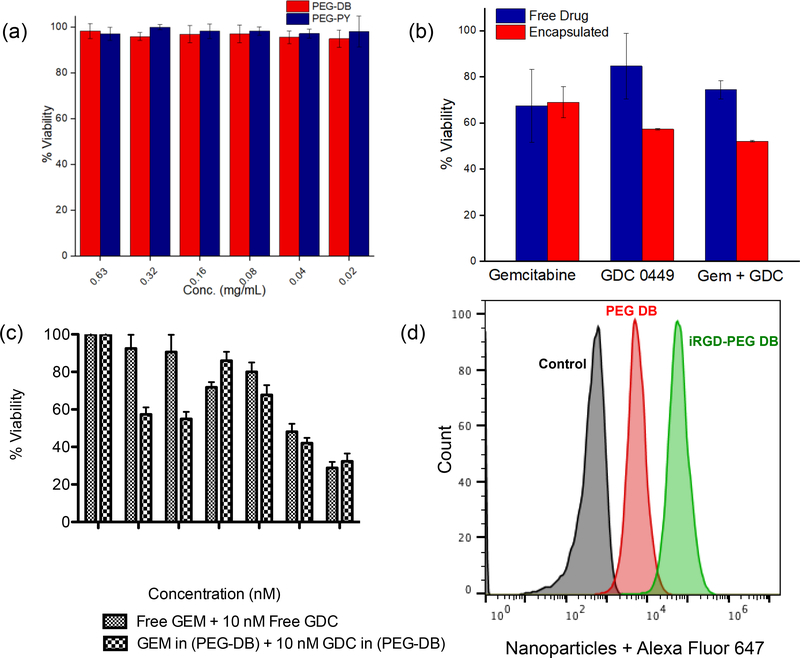

In vitro cytotoxicity of pH-responsive nanoparticles.

We have then evaluated the cellular compatibility of the block copolymers and in vitro performance of drug-loaded PEG-DB and PEG-PY nanoparticles to suppress growth and proliferation of two pancreatic cancer cell lines, such as BxPC-3 and Mia PaCa-2. We set out to show the efficiency of the synthesized nanoparticles in these two types of cell lines, such as Mia PaCa-2, which shows KRAS mutation, and BxPC-3 which contains wild-type RAS and are not RAS activated [50]. This is to note that, KRAS mutation is more prevalent in human pancreatic cancer. In addition, these two cell lines also show different metabolic activity. Mia PaCa-2 is strongly glycolytic, while BxPC-3 is mildly glycolytic, and this is well postulated that chemotherapeutic success critically depends on the metabolic profiling of target cancer cells [51]. First, we evaluated the viability of Mia PaCa-2 cells when treated with PEG-DB and PEG-Py block copolymers without the drug, to assess the inherent cytotoxicity of nanoparticles alone (Figure 4a). We have also studied the viability of fibroblast cells when treated with drug-free nanoparticles as well as with the structural components of the particle-forming block copolymers separately, such as, PEG (the hydrophilic block of the copolymer), poly (carbonate) block appended with N, N′-dibutyl ethylenediamine (PC-DB, the hydrophobic block of the copolymer) and N, N′-dibutyl ethylenediamine (DB) alone (Figure S12, Supporting Information). For therapeutic efficiency study, the cells were treated with single or combination therapy of GEM and GDC 0449, either alone or encapsulated within PEG-DB nanoparticles (Figure 4b-c). Figure 4a reveals that after 48 hours of treatment, block copolymers PEG-DB (4) and PEG-PY (5), in their unassembled form, are non-toxic to Mia PaCa-2 cells within a concentration range of 1.25 to 0.2 mg/mL. Figure 4b shows that GEM encapsulated within PEG-DB at a concentration of 0.8 μM is more effective when combined with PEG-PY encapsulated GDC (1.5 μM) than the combination of free drugs in BxPC-3 cell lines in a similar concentration. We also observed that, when Mia PaCa-2 cells were treated with increasing concentration of GEM in the presence of 10 nM of GDC (either free or encapsulated within PEG-PY system), nanoparticle bound formulations brought in enhanced more cytotoxic onslaught than combination of free drugs (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

(a) Both PEG-DB and PEG-PY block copolymers in their unassembled form are non-toxic to MIAPaCa-2 cells (N = 3) (b) Cell viability for GEM (0.8 μM) encapsulated in PEG-DB and GDC 0449 (1.5 μM) in PEG-PY NPs in BxPC-3 cells. (c) Cellular viability studies of Mia PaCa-2 cells when treated with increasing concentration of GEM in either free or PEG-DB encapsulated form in the presence of 10 nM GDC (free or PEG-PY encapsulated form, N = 3) (d) Immobilization of iRGD peptide on PEG-DB nanoparticles enhances uptake of the nanoparticles in Mia PaCa-2 cells at 37 °C.

Cellular and tissue internalization of nanoparticles.

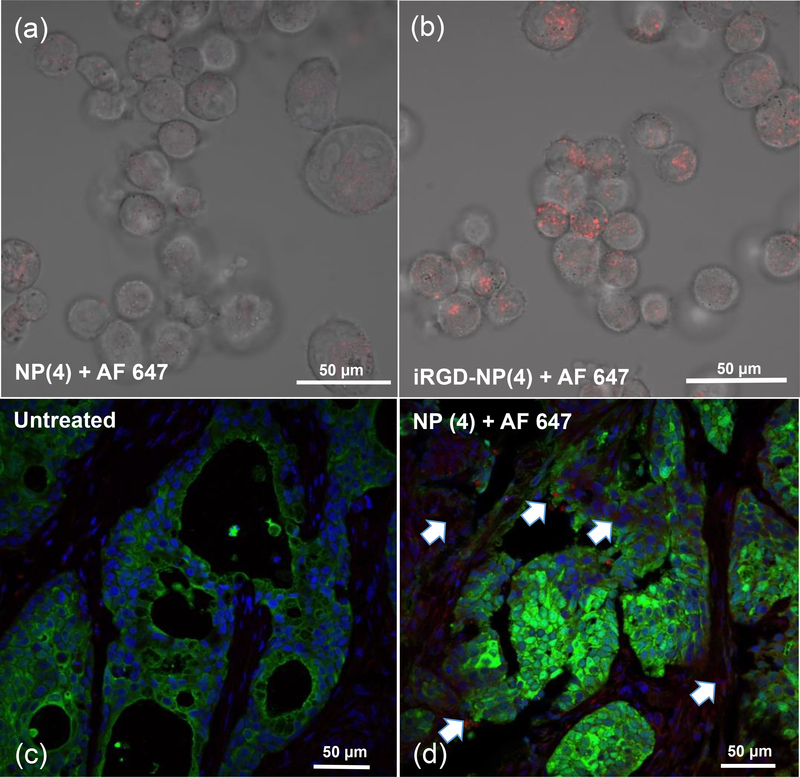

To investigate the potential of PEG-b-polycarbonate block copolymers to form nanoparticles with enhanced cellular uptake and tissue penetration property to use in desmoplastic PDAC tumor, we have immobilized a cyclic peptide, iRGD, onto PEG-DB nanoparticle surface (Figure 1b, S13, Supporting information). This cyclic peptide has been reported to bind selectively to the integrin (αvβ5) and Neuropilin receptors overexpressed in the tumor blood vessels thus enhancing the capabilities of nanoparticles carrying encapsulated materials to penetrate further into the desmoplastic stroma of PDAC microenvironment [52, 53]. Polymersomes decorated with iRGD were synthesized by conjugating the peptide to block copolymer (4) through Cu2+-catalyzed azide-alkyne click chemistry and characterized using CD (supporting information, Figure S13) and IR spectroscopy. Since Mia PaCa-2 cells have been well reported to bear integrin receptors [54], we have conducted Flow cytometry experiments in MIA PaCa-2. Flow cytometry data clearly showed significant uptake of iRGD-decorated PEG-DB nanoparticles compared to untargeted polymersomes, which is a contribution from both non-specific endocytosis and receptor-mediated uptake of targeted nanoparticles (Figure 4d). Confocal fluorescence microscopy experiment supported the flow cytometric observation in the same cell line, where an augmented cell-associated fluorescence from iRGD-containing PEG-DB nanoparticles labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 was observed within the cytosol of MIAPaCa-2 cells (Figure 5b) compared to cells treated with non-targeted nanoparticles (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Top panel: Confocal fluorescence micrograph shows augmented cellular uptake in MiaPaCa-2 cells for iRGD functionalized PEG-DB nanoparticles (a) unfunctionalized PEG-DB nanoparticles (b) iRGD functionalized PEG-DB nanoparticles. Bottom panel: Histology of tumor section in xenograft bearing mice i.v. injected with PEG-DB AF 647 nanoparticles showing the presence of nanoparticles (red) in (d) compared to histology of the tumor section from untreated mice (c). Green: FITC labeled S100 positive xenograft cells, Red: Alexa Fluor 647 labelled nanocarrier, Blue: Cell nuclei.

To obtain preliminary information on the internalization capacity of pH-responsive nanoparticles within cancer microenvironment in vivo in a mouse model, we have grown BxPC-3 tumor xenograft in immune compromised nude mice. Due to the slow growth rate of MiaPaca-2 cells as xenografts; we used BxPC-3 cells, which formed the tumor xenograft within 3 weeks. We have selected PEG-DB as a representative class of nanoparticles and injected the labeled nanoparticle solution through tail-vein. After 6 hours post circulation and necropsy, we observed that i.v. administered, fluorescently tagged PEG-DB nanoparticles accumulating in tumor microenvironment as visualized in the histologic cross-section image of excised tumor tissue in Figure 5(d). This result is consistent with the notion that most nanoparticles within the size range of 100–150 nm are most likely accumulated into tumor microenvironment by size-dependent, passive targeting mechanism.

CONCLUSIONS

In this report, we describe the synthesis and efficiency studies of poly (carbonate)-derived amphiphilic block copolymeric assembly with tunable pH-responsivity. We observed that these assemblies form stable nanoparticles that can encapsulate a drug combination applicable to pancreatic cancer. By stoichiometric mixing of nanoparticles formed from different types of pH-responsive amphiphilic block copolymers, it was possible to achieve drug release as a function of pH corresponding to extracellular tumor microenvironment or in intracellular milieu mimicking pH. Currently, we are working on the extensive intracellular and in-vivo investigations of targeted PEG-b-poly (carbonate) pH-responsive platform for PDAC drug delivery applications.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

pH-responsive nanocarriers are synthesized for pancreatic cancer

Nanocarriers encapsulate and release Gemcitabine and GDC 0449 (an Hedgehog inhibitor).

Nanocarriers mixed stoichiometrically to obtain compartment-specific drug release.

Nanocarrier delivery suppressed proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells

pH-responsive nanocarriers accumulated inside tumor microenvironment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIH grant number P20 GM109024 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) and the COBRE Animal Studies Core Facility. TEM material is based upon work supported by the NSF under Grant No. 0923354. Funding for the Core Biology Facility used in this publication was made possible by NIH Grant Number 2P20 RR015566 from the National Center for Research Resources. SM acknowledges the support through the NIH grant 1R01 GM 114080 (NIGMS). Partial support for this work was received from NSF Grant No. IIA-1355466 from the North Dakota Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) through the Center for Sustainable Materials Science. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The authors would like to thank Scott Payne and Jayma Moore for TEM imaging.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting information

The supporting information is available free of charge on the Elsevier website at DOI: Supporting information includes the synthesis and characterization of pH-responsive block copolymers.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Gerweck LE, Seetharaman K. Cellular pH Gradient in Tumor versus Normal Tissue: Potential Exploitation for the Treatment of Cancer. Cancer Research 1996;56:1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Koltai T Cancer: Fundamentals behind pH targeting and the double edged approach. Oncotargets and Therapy 2016;9:6343–6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Martin GR, Jain RK. Noninvasive measurement of interstitial pH profiles in normal and neoplastic tissue using fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy. Cancer Research 1994;54:5670–5674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chauhan VP, Jain RK. Strategies for advancing cancer nanomedicine. Nat Mater 2013;12:958–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bailey JM, Mohr AM, Hollingsworth MA. Sonic Hedgehog Paracrine Signaling Regulates Metastatis and Lymphangiogenesis in Pancreatic Cancer. Oncogene 2010;28:3513–3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cruz-Monserrate Z, Roland CL, Deng D, Arumugam T, Moshnikova A, Andreev OA, et al. Targeting Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Acidic Microenvironment. Scientific Reports 2014;4:4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dickson I Stromal-cancer cell crosstalk supports tumour metabolism. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Amp; Hepatology 2016;13:558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2012;62:10–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dreaden EC, Kong YW, Morton SW, Correa S, Choi KY, Shopsowitz KE, et al. Tumor-Targeted Synergistic Blockade of MAPK and PI3K from a Layer-by-Layer Nanoparticle. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:4410–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Davis ME, Chen Z, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008;7:771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huber V, Camisaschi C, Berzi A, Ferro S, Lugini L, Triulzi T, et al. Cancer acidity: An ultimate frontier of tumor immune escape and a novel target of immunomodulation. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2017;43:74–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kato Y, Ozawa S, Miyamoto C, Maehata Y, Suzuki A, Maeda T, et al. Acidic extracellular microenvironment and cancer. Cancer Cell International 2013;13:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Harguindey S, Reshkin SJ. “The new pH-centric anticancer paradigm in Oncology and Medicine”; SCB, 2017. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2017;43:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Granja S, Tavares-Valente D, Queirós O, Baltazar F. Value of pH regulators in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2017;43:17–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Akakura N, Kobayashi M, Horiuchi I, Suzuki A, Wang J, Chen J, et al. Constitutive Expression of Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1α Renders Pancreatic Cancer Cells Resistant to Apoptosis Induced by Hypoxia and Nutrient Deprivation. Cancer Research 2001;61:6548–6554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Feig C, Gopinathan A, Neesse A, Chan DS, Cook N, Tuveson DA. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2012;18:4266–4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2007;26:225–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kulkarni P, Haldar MK, You S, Choi Y, Mallik S. Hypoxia-Responsive Polymersomes for Drug Delivery to Hypoxic Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Biomacromolecules 2016;17:2507–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shields DJ, Niessen S, Murphy EA, Mielgo A, Desgrosellier JS, Lau SK, et al. RBBP9: a tumor-associated serine hydrolase activity required for pancreatic neoplasia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010;107:2189–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor microvasculature and microenvironment: Targets for anti-angiogenesis and normalization. Microvascular Research 2007;74:72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cancer Cell Metabolism: Warburg and Beyond. Cell 2008;134:703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kimbrough CW, Khanal A, Zeiderman M, Khanal BR, Burton NC, McMasters KM, et al. Targeting acidity in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Multispectral optoacoustic tomography detects pH-low insertion peptide probes in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research 2015;21:4576–4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Quadir MA, Morton SW, Deng ZJ, Shopsowitz KE, Murphy RP, Epps TH, et al. PEG–Polypeptide Block Copolymers as pH-Responsive Endosome-Solubilizing Drug Nanocarriers. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2014;11:2420–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dreaden EC, Morton SW, Shopsowitz KE, Choi J-H, Deng ZJ, Cho N-J, et al. Bimodal Tumor-Targeting from Microenvironment Responsive Hyaluronan Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2014;8:8374–8382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Engler AC, Bonner DK, Buss HG, Cheung EY, Hammond PT. The synthetic tuning of clickable pH responsive cationic polypeptides and block copolypeptides. Soft Matter 2011;7:5627–5637. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Matsumoto A, Yoshida R, Kataoka K. Glucose-Responsive Polymer Gel Bearing Phenylborate Derivative as a Glucose-Sensing Moiety Operating at the Physiological pH. Biomacromolecules 2004;5:1038–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rodríguez-Hernández J, Lecommandoux S. Reversible Inside−Out Micellization of pH-responsive and Water-Soluble Vesicles Based on Polypeptide Diblock Copolymers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2005;127:2026–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Karaca M, Dutta R, Ozsoy Y, Mahato RI. Micelle Mixtures for Coadministration of Gemcitabine and GDC-0449 To Treat Pancreatic Cancer. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2016;13:1822–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sanders DP, Fukushima K, Coady DJ, Nelson A, Fujiwara M, Yasumoto M, et al. A Simple and Efficient Synthesis of Functionalized Cyclic Carbonate Monomers Using a Versatile Pentafluorophenyl Ester Intermediate. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010;132:14724–14726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu J, Liu W, Weitzhandler I, Bhattacharyya J, Li X, Wang J, et al. Ring-Opening Polymerization of Prodrugs: A Versatile Approach to Prepare Well-Defined Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2015;54:1002–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhou K, Liu H, Zhang S, Huang X, Wang Y, Huang G, et al. Multicolored pH-Tunable and Activatable Fluorescence Nanoplatform Responsive to Physiologic pH Stimuli. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012;134:7803–7811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ma X, Wang Y, Zhao T, Li Y, Su L-C, Wang Z, et al. Ultra-pH-Sensitive Nanoprobe Library with Broad pH Tunability and Fluorescence Emissions. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014;136:11085–11092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gao W, Chan JM, Farokhzad OC. pH-Responsive Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2010;7:1913–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Carr RM, Fernandez-Zapico ME. Pancreatic cancer microenvironment, to target or not to target? EMBO Molecular Medicine 2016;8:80–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang X, Lin Y, Gillies RJ. Journal of nuclear medicine 2010;51:1167–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gilles RJ, Liu Z, Bhujwalla Z. 31P-MRS measurements of extracellular pH of tumors using 3-aminopropylphophonate. The American Journal of Physiology 1994;267:C195–C203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Estrella V, Chen T, Lloyd M, Wojtkowiak J, Cornell HH, Ibrahim-Hashim A, et al. Acidity generated by the tumor microenvironment drives local invasion. Cancer Research 2013;73:1524–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nakashima H, Nakamura M, Yamaguchi H, Yamanaka N, Akiyoshi T, Koga K, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB contributes to hedgehog signaling pathway activation through sonic hedgehog induction in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Research 2006;66:7041–7049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gu D, Schlotman KE, Xie J. Deciphering the role of hedgehog signaling in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Biomedical Research 2–16;30:353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Engler AC, Chan JMW, Coady DJ, O’Brien JM, Sardon H, Nelson A, et al. Accessing New Materials through Polymerization and Modification of a Polycarbonate with a Pendant Activated Ester. Macromolecules 2013;46:1283–1290. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dan K, Bose N, Ghosh S. Vesicular assembly and thermo-responsive vesicle-to-micelle transition from an amphiphilic random copolymer. Chemical Communications 2011;47:12491–12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Discher DE, Eisenberg A. Polymer Vesicles. Science 2002;297:967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Du J, Armes SP. pH-Responsive Vesicles Based on a Hydrolytically Self-Cross-Linkable Copolymer. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2005;127:12800–12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mai Y, Eisenberg A. Self-assembly of block copolymers. Chemical Society reviews 2012;41:5969–5985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kalyanasundaram K, Thomas JK. Environmental effects on vibronic band intensities in pyrene monomer fluorescence and their application in studies of micellar systems. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1977;99:2039–2044. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Yamamoto Y, Yasugi K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y, Kataokaa K. Temperature-related change in the properties relevant to drug delivery of poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(D,L-lactide) block copolymer micelles in aqueous milieu. Journal of Controlled Release 2002;82:359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Maksimenko A, Caron J, Mougin J, Desmaële D, Couvreur P. Gemcitabine-based therapy for pancreatic cancer using the squalenoyl nucleoside monophosphate nanoassemblies. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2015;482:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Borad MJ, Vernillet L, Darbonne WC, Mackey H, et al. A first-in-human, first-in-class, phase (ph) I study of systemic Hedgehog (Hh) pathway antagonist, GDC-0449, in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008;26:3516–3516. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sandhiya S, Melvin G, Kumar SS, Dkhar SA. The dawn of hedgehog inhibitors: Vismodegib. Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics 2013;4:4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Deer EL, Gonzalez-Hernandez J, Coursen JD, Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, et al. Phenotype and Genotype of Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines. Pancreas 2010;39:425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Daemen A, Peterson D, Sahu N, McCord R, Du X, Liu B, et al. Metabolite profiling stratifies pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas into subtypes with distinct sensitivities to metabolic inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015;112:E4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Liu X, Lin P, Perrett I, Lin J, Liao YP, Chang CH, et al. Tumor-penetrating peptide enhances transcytosis of silicasome-based chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation 2017;127:2007–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sugahara KN, Braun GB, de Mendoza TH, Kotamraju VR, French RP, Lowy AM, et al. Tumor-Penetrating iRGD Peptide Inhibits Metastasis. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2015;14:120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Loehr M, Trautmann B, Goettler M, Peters S, Zauner I, Maier A, et al. Expression nad function of receptors for extracellular matrix proteins in human ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas. Pancreas 1996;12:248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.