Abstract

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an optical technique that uses backscattered light to highlight intrinsic structure, and when applied to brain tissue, it can resolve cortical layers and fiber bundles. Optical coherence microscopy (OCM) is higher resolution (i.e., 1.25 μm) and is capable of detecting neurons. In a previous report, we compared the correspondence of OCM acquired imaging of neurons with traditional Nissl stained histology in entorhinal cortex layer II. In the current method-oriented study, we aimed to determine the colocalization success rate between OCM and Nissl in other brain cortical areas with different laminar arrangements and cell packing density. We focused on two additional cortical areas: medial prefrontal, pre-genual Brodmann area (BA) 32 and lateral temporal BA 21. We present the data as colocalization matrices and as quantitative percentages. The overall average colocalization in OCM compared to Nissl was 67% for BA 32 (47% for Nissl colocalization) and 60% for BA 21 (52% for Nissl colocalization), but with a large variability across cases and layers. One source of variability and confounds could be ascribed to an obscuring effect from large and dense intracortical fiber bundles. Other technical challenges, including obstacles inherent to human brain tissue, are discussed. Despite limitations, OCM is a promising semi-high throughput tool for demonstrating detail at the neuronal level, and, with further development, has distinct potential for the automatic acquisition of large databases as are required for the human brain.

Keywords: optical imaging, human brain, isocortex, limbic, neuron, tissue, validation

INTRODUCTION

MRI has long been recognized as a highly useful tool in the study of the human brain: in the shape and volume of its structures across development, adulthood, aging and disease processes in a large scale, three-dimensional and longitudinal manner (Ashburner 2012; Coupe et al. 2017; Da et al. 2014; Datta et al. 2017; Falahati et al. 2017; Fischl 2012; Jenkinson et al. 2012; Reuter et al. 2012; Salat et al. 2004; Van Essen 2012; Fischl et al. 2004). Though MRI has provided an enormous amount of data, and with 7T MRI now achieves a submillimeter resolution and the visualization of cortical layers, it notably lacks the more cellular resolution needed to distinguish specific area differences or specific neuronal populations. Disease states, for example, may be associated not only with neuronal loss, but more particularly, with neuron-specific loss.

Significantly higher resolution brain mappings are underway to address this problem. The Big Brain project aims to correlate MRI and histology using a large scale three-dimensional method (Amunts et al. 2013). Classical neuroanatomical histology and immunohistochemistry (e.g. Ding et al. 2016) remain acceptable options, but are notoriously labor intensive. In addition, the necessary tissue sectioning and histological processing result in frequent distortions that seriously hinder the alignment of tissue sections into three-dimensional models. A means of studying cortical architecture, either cyto- or myeloarchitecture, in a high-throughput acquisition protocol is urgently needed. One relatively new and promising approach to this problem is optical coherence microscopy (OCM).

OCM is a high-resolution optical technique (Huang et al. 1991) that potentially combines both the resolution obtained with a compound microscope and the three-dimensional capacity of MRI. With continued development - of hardware, software, and automation of the optical imaging systems - high through-put acquisition of neuronal brain architecture could be within reach (Axer et al., 2016; Magnain et al., 2014; Ragan et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2016). Recent studies have demonstrated that optical coherence tomography and microscopy (respectively, low (OCT) and high (OCM) resolution) resolve the intrinsic contrast of human brain structure (no stain nor dye needed) visualized by back scattered light, and can reveal cortical layers, fibers, and even neurons(Assayag et al. 2013; Magnain et al. 2015; Magnain et al. 2014; Wang 2017; Wang et al. 2014). OCM is effective on immersion-fixed human brain tissue, does not require histological staining, yet yields excellent resolution, is not dependent on the length of time in fixation (Magnain et al. 2014), and acquires images of the tissue block before sectioning, thus reducing greatly the distortions. These are distinct advantages over techniques such as Clarity, which have tissue size limitations and require, especially for the human brain, complex clearing and staining protocols (Chung et al. 2013; Tomer et al. 2014).

Our long-term objective is to establish OCM as a viable means to study morphological changes and neuron populations, through an undistorted three-dimensional high-throughput method in the human brain. It would facilitate the direct visualization of three-dimensional neuronal organization, such as spacing or density of cellular minicolumns. For this paper, the immediate goal was to compare the performance of OCM with regard to histological resolution in two cortical areas different from the highly specialized EC that has been previously investigated (Magnain et al. 2015). This will serve as an important calibration for what level of performance can be expected with current technology, and a guide for further hardware, software, and analysis development.

In a previous report, we compared the correspondence of OCM-acquired imaging of neurons with traditional Nissl stained histology in entorhinal cortex layer II (Magnain et al. 2015), and were able to show an excellent match between neurons as imaged by OCM and by subsequent Nissl staining. Since, however, entorhinal cortex has distinctively large stellate cells in layer II which are well-isolated by intervening dendritic bundles, we were concerned that this might be a best-case example for imaging by OCM. Thus, we undertook this methods-oriented study to determine the match success rate for two additional cortical areas: medial prefrontal, pre-genual Brodmann area (BA) 32 and lateral temporal BA 21. Both of these areas have different architectonics and function from the entorhinal cortex (i.e., smaller cells, different cell packing, and differing amounts of myelination), making them well-suited to test the capability of OCM in different microenvironments. In brief, BA 21 is a higher-order visual association cortex with medium myelin content (Brodmann 1909; Economo and Koskinas 1925). It has a relatively small layer III with low cell packing density, a thin layer IV, and wide infragranular layers V and VI, with large pyramidal cells in layer V (Mai and Paxinos 2007). BA 32 is a limbic association area that has light myelination. It has large pyramids in layer IIIc, a dysgranular layer IV, relatively sparse layer Vb, and a trend for elongated neurons in layer VI (Palomero-Gallagher et al. 2008; Palomero-Gallagher et al. 2013; Vogt et al. 2013). We asked how the cortical microenvironment affects OCM acquired neuronal imaging? We also took this opportunity to summarize technical and methodological developments.

Our experimental design includes, in outline, imaging small blocks of tissue by OCM, subsequently vibratome-sectioning the tissue block, harvesting the vibratome section corresponding to the imaged OCM blockface, processing this with Nissl histology, and finally registering and comparing the two datasets - the OCM acquired blockface and vibratome-sectioned post-imaging Nissl stained section (Fig. 1).

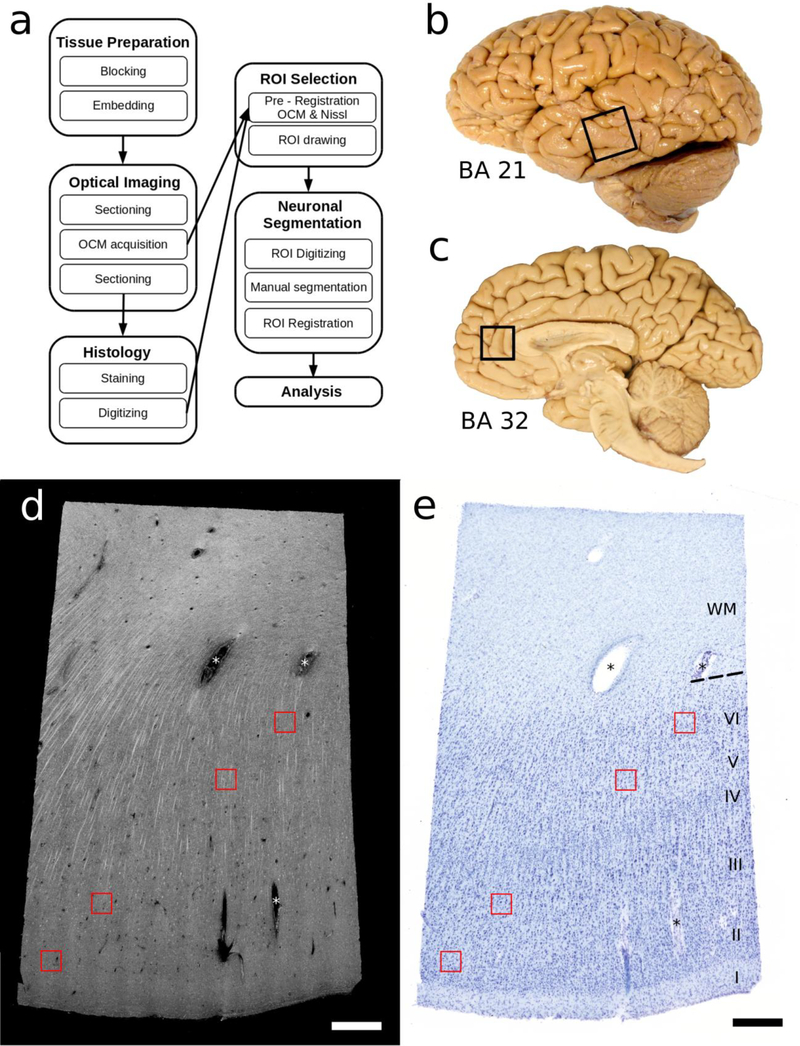

Fig 1. Overview.

a) Workflow diagram. b) Lateral view of the human brain where box outlines part of BA 21, middle temporal area, dissected as tissue blocks. c) Medial view of the human brain with box outlining where BA 32, pre-genual cingulate area, was blocked. d) Tissue from BA 21 as imaged by OCM (at one depth) and e) the corresponding Nissl stained histological section digitized with a 4x objective (40x magnification). OCM and Nissl are in register with each other and four regions of interest (ROI, the red inset boxes) delineate various layers (i.e. layer II, III, V and VI). Each ROI is 200 μm × 200 μm. Scale bar = 500 μm. OCM=optical coherence microscopy, BA=Brodmann’s area, ROI=region of interest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Samples and Demographics

Six human brain hemispheres were obtained from Massachusetts General Hospital Autopsy Suite (Boston, MA, USA). See Table 1 for the demographic and diagnostic details. The demographics were as follows: three females and three males, with a mean and standard deviation of age of 55.7 ± 16 years old. The post-mortem interval for the brains was less than 24 hours, except for case 6 (30 hours). All six brains were clinical controls, but three had a few age-related neurofibrillary tangles (i.e. Braak and Braak stage I pathology, n=3; Braak and Braak 1991), demonstrated with ThioflavinS staining (cases #3, 4, 5) and one (case #5) had evidence of hypertensive cerebral vasculopathy and ischemic changes. The brains were thoroughly fixed by immersion in 10% formalin for at least two months. The study was approved by the internal review board (IRB) of the Massachusetts General Hospital and carried out according to current ethical standards.

Table 1 –

Brain tissue demographics.

| Case | Age, Sex | PMI (hrs) | Clinical Dx | Pathology Dx | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45, F | <24 | Control | Control | Lung disease |

| 2 | 74, F | <24 | Control | Control | MI |

| 3 | 68, M | <24 | Control, hypertension | Control, BBI-II | MI |

| 4 | 59, M | 20 | Control | Control, BBI, reactive gliosis | Surgery complications, Alcoholism |

| 5 | 58, M | <24 | Control | Control, BBI, ischemic changes | Lung disease |

| 6 | 30, F | 30 | Control | Control | Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

Abbreviations: BB, Braak and Braak stage; Dx, diagnosis; MI, myocardial infarction, PMI, post mortem interval, F, female; M, male.

Overview

Fig. 1a illustrates the workflow adopted for this study. Since this investigation aimed to standardize and optimize the technical aspects of OCM in human brain specimens, each step is described in detail in the following paragraphs.

Tissue Preparation

Three blocks from three different cases were dissected from BA21, on the lateral side of the hemispheres (Fig. 1b) and three blocks from three cases from BA32, on the medial side, anterior to the corpus callosum (Fig. 1c). Each tissue block spanned from the pia surface to white matter but had a small width (2 × 3 × 10 mm3 in total size). To be able to vibratome-section these small blocks, the tissue samples were embedded in melted oxidized agarose activated with a borohydride-borate solution, which covalently cross-links the tissue and agarose (Ragan et al. 2012).

Optical Imaging

Samples were positioned on a motorized XY translation stage. The vibratome is integrated to our OCM rig, where the z movement is controlled by a motorized Z stage (Ragan et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2017). Prior to OCM imaging, five 50 μm thick sections (#1–5) from each block were vibratome-sectioned to microscopically assess the histological quality (Fig. 1a). This step also assures a flat blockface, which is important for high imaging quality. The remaining tissue block was then imaged by OCM.

Our microscope is a spectral domain OCM (Magnain et al. 2015; Srinivasan et al. 2012). The light source is provided by a superluminescent diode (LS2000B, Thorlabs, Inc., New Jersey, USA), centered around 1310 nm with a full width at half maximum of 170nm, yielding an axial resolution of 3.5 μm in tissue (4.7 μm in air). The spectrometer is made of a grating and a 1024-pixel InGaAs line scan camera (1024-LDH, Goodrich-Sensors Unlimited, Princeton, New Jersey), providing a depth of field of 1.5 mm in tissue (2.2 mm in air) and a pixel size in depth of 2.9 μm. In order to image neurons, a high numerical aperture (NA) objective has to be used in the sample arm to achieve high lateral resolution. The objective integrated in the OCM set up is a 40x water immersion objective with a NA of 0.8 (Olympus LUMPLANFL/IR 40x W), resulting in a lateral resolution of 1.25 μm, and a depth of focus of 10 μm. The en-face field of view is 400 μm × 400 μm and our system records 512 pixels in each direction, which gives an isotropic lateral pixel size of 0.78 μm.

Custom made software controls both the stage and the OCM acquisition, making the imaging of the blockface fully automatic (Wang et al. 2017). In specific, the sample is moved in a serpentine pattern with 25% overlap between adjacent volumes; after each individual move, an OCM volume is recorded. In order to compare the OCM data with the same Nissl-stained section, the top 50 μm of tissue has to be imaged (e.g. the thickness of the histological section). For this, we focused the objective at five different depths in the tissue, starting at 5 μm beneath the blockface surface and then re-focusing every 10 μm until the last focus depth (at 45 μm) (Magnain et al. 2015). Once the five OCM depths were acquired over the full blockface, the sample was translated to the vibratome and three more slices (#6–8) of 50 μm thickness were collected. Vibratome section #6 for each sample corresponds to the 5 planes of OCM imaged tissue.

The OCM dataset is then post-processed to obtain a 2D projection. We used frequency compounding technique (six optical frequency bands) to reduce speckle noise, resulting in increased contrast-to-noise ratio (Magnain et al. 2016). The maximum intensity projection was performed on each volume for the 10 μm around the focus plane. Then, those images were registered using a Fiji plug-in based on the Fourier shift theorem (Preibisch et al. 2009) and the full slice was reconstructed by stitching the images together for every depth. An OCM slice reconstruction is shown in Fig. 1d. Some stitching artifacts are evident, due to misalignment and angular compounding.

Histology

Vibratomed sections corresponding to the OCM imaging plane (i.e. histology section #6) were stained with thionin for cell bodies. The section was mounted onto a gelatin dipped (“subbed”) glass slide and dried overnight. After defatting in chloroform-alcohol, the section was over-stained for three minutes in 0.05% thionin (pH 4.8), differentiated and dehydrated in ascending series of alcohol, and coverslipped from xylene with Permount.

The Nissl stained sections were first digitized using an 80i Nikon Microscope (Microvideo Instruments, Avon, MA) with a 4x objective (40x total magnification; Fig. 1e), which results in images with a 1.85 μm pixel size. The virtual tissue workflow provided from Stereo Investigator (MBF Bioscience, Burlington, VT) automatically acquired the images. The specific regions of interest, ROIs (red boxes in Fig. 1e) will be digitized again later at higher magnification.

ROI selection

We selected eight ROIs in the relevant OCM/Nissl sections, located both in the infra- and supragranular layers of the tissue, but avoiding layer IV because of the characteristically small neurons in area 21 and the uncertain borders of this layer in dysgranular BA32. For each block, we selected 2 ROIs in layers II, III, V, VI. One ROI for each layer is represented on Fig.1d and 1e by a red box. We pre-registered the Nissl stained slices to the OCM images, using the corners of the tissue sections and prominent blood vessels as landmarks (asterisks * in Fig. 1e). Due to the histological distortions, we implemented a nonlinear transformation between manually selected landmarks on both image modalities (OCM and Nissl; Magnain et al. 2015) based on the Thin-Plate Splines (Bookstein 1989) deformation model using the freely available ITK library (Yoo et al. 2002). Our implementation requires the pixel size of both images to be the same, so the digitized Nissl stained slices are up-sampled to the pixel size of the OCM (i.e., 0.78 μm). Fig. 1d, 1e shows the registration between the two datasets (OCM and the corresponding Nissl). After this initial registration, the ROIs (areas of 200 μm × 200 μm) were drawn on both datasets.

Neuronal segmentation

To evaluate the quality of match between the OCM-imaged and histological databases at the level of individual neurons, the Nissl ROIs (the red boxes) were digitized at a higher magnification (200x, using a 20x objective where the pixel size is 0.37 μm). For each ROI digitization, we acquired an image every 1 μm in depth. The full depth of the Nissl stained tissue (i.e., a “50μm” vibratome section) varied from case to case, section to section, and from ROI to ROI within the same section after shrinkage. Thus, the number of focal depths ranged from 12 to 28. Images were gathered in consecutive groups of four images (an arbitrary choice), and the Fiji plug-in “Stack focuser” used to make a single image, totaling 4 μm, resulting in a final ROI imaged at 3 to 7 different focus depths (i.e. 12–28μm; Fig. 2c, Depths 1–5). We also used the plug-in to generate the focused imaged from the entire stack of depth acquisitions (Fig 2c, last column, “all”).

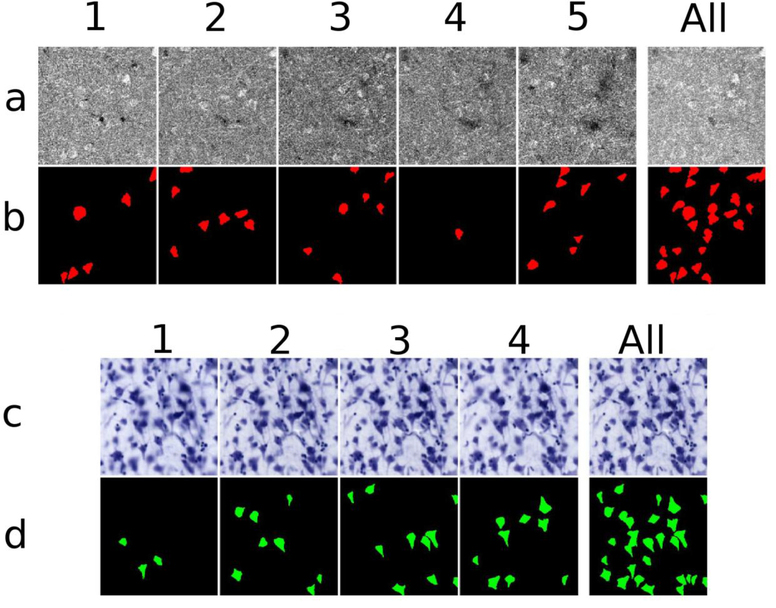

Fig 2. OCM and Nissl segmentations.

a) OCM imaging depths 1–5; b), OCM neuronal segmentation labeled in red; c) Nissl focal depths 1–4; d) Nissl neuronal segmentation labeled in green. Each number, across the rows, represents one depth of 10 μm. The Nissl images appear slightly blurry due to the registration process. The last column, at the right, illustrates stacked images for each modality for the actual data and neuronal segmentation. Each square represents an area of 200 μm × 200 μm.

Next, we manually labeled neurons in both datasets (Fig 2a and 2c). For the Nissl segmentation, we used the following criteria: a) expected neuron-like shape, b) at least one visible proximal dendrite, c) appropriate size for a neuron (i.e. is not glia or a neuron particle), and d) a visible nucleus/nucleolus (Fig. 2d). The criteria for the OCM segmentation (Fig. 2b) were similar: a) putative neuronal shapes, b) neuronal size, and c) an intensity higher than that of the surrounding tissue, but we relaxed the requirements for a nucleus/nucleolus and discernible dendrite in OCM. We did not tag hollow or apparently partial neurons and were intentionally conservative on labeling OCM neurons that showed robust intensity but no clear neuronal shape or dendrites. The digitized Nissl stained ROI (20x objective) and the respective segmentation were registered again to the OCM images by non-linear transformation as previously described, using the neurons as fiducial landmarks. The downsampling of the Nissl from 0.37 μm to 0.78 μm, in order to register with OCM, accounts for the blurry Nissl images in Fig. 2c.

Analysis

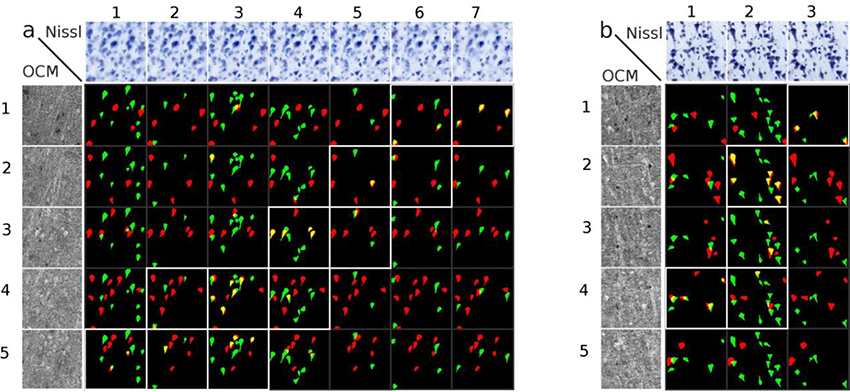

Once both datasets were labeled, the neuron colocalization analysis was undertaken; this is illustrated as a colocalization matrix (Fig. 3), where the OCM imaged planes are displayed as rows: 1–5 depths, Nissl focal planes are displayed as columns 1–7, and the segmentations of OCM neurons in red and Nissl stained neurons in green. The colocalization of neurons observed by OCM and Nissl is shown in yellow with these overlapping neurons revealing a diagonal pattern, highlighted with white boxes (Fig. 3). On rare occasions two neurons appear at the same location but at different depth in the tissue (matrix panel 2,3 in Fig 3a) and these off-diagonal overlapping neurons were not counted in the final results. The last row (the last depth in OCM) in Fig. 3b did not give any colocalized neurons because the Nissl section was thinner than the imaged OCM and was not counted in the final results.

Fig 3. Colocalization matrix.

Two examples from BA 21 (a, b) showing the Nissl focal depths (top row), the OCM imaging depths (left column), and the colocalization matrix. For each depth, neurons visualized by OCM neurons are in red, Nissl stained neurons in green, and the colocalized neurons in yellow. The colocalized neurons show a diagonal pattern (boxes outlined in white) in the co- localization matrix. Each square represents an area of 200 μm × 200 μm.

The colocalization of neurons was assessed as percentage. The OCM percentages (referred to as OCM colocalization) were determined as the number of colocalized neurons out of the total number of neurons segmented on the OCM images, while the Nissl percentages (referred to as Nissl colocalization) were calculated as the number of colocalized neurons out of the total number of neurons segmented on the Nissl images.

Fiber density

Since OCM is sensitive to any scattering structures, structures besides neurons appear as well. In particular, myelin, with a high refractive index, highly scatters and backscatters light. We visually evaluated the fiber content for each ROI using the OCM imaging independently of location in the brain, i.e. area and layer. We defined four categories based on the fiber density and patterning: +: individual and sparse fibers, ++: individual and dense fibers, +++: small and dense bundles, and ++++: large and dense bundles.

RESULTS

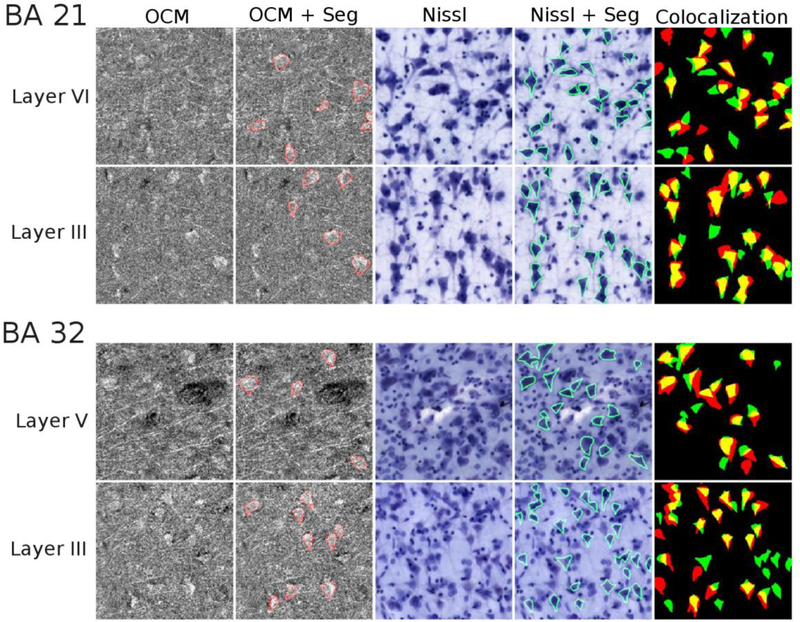

Figure 4 illustrates the results of the segmentation and colocalization for four different ROIs. The selected ROIs are located in layers VI and III for BA 21 and in layers V and III for BA 32. The first two columns are the OCM image without and with the neuron outlines respectively at depth 2. As the overlay of the different depths induces a loss of neuron resolution (as seen in the last column of Fig. 2a), we illustrated only the one depth in this figure. Columns 3 and 4 are the focused image of the 20x Nissl stained section without and with the neurons outlines, and the last column shows the colocalization of the segmented neurons. The colocalization percentages for each layer (mean of the 2 boxes) are given in Tables 2 (for BA 21) and 3 (for BA 32).

Fig. 4. Colocalization of segmented neurons in supra- and infragranular layers in BA 21 and 32.

The OCM data (at a single imaging depth, for better resolution) are illustrated without and with the neuron segmentation outlines (columns 1–2), Nissl through-focus stack without and with the neuron segmentation outlines (columns 3–4), and the segmentation overlay with OCM (red), Nissl (green), and colocalized neurons (yellow) in column 5. Each square represents an area of 200 μm × 200 μm.

Table 2 –

Colocalization percentages for each case, block and layer in BA21.

| Table 2 – BA 21 | Layer | OCM % | Nissl % | Fiber content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 45F | II | 54% | 44% | + |

| III | 77% | 79% | +++ | |

| V | 61% | 60% | ++++ | |

| VI | 64% | 53% | ++++ | |

| Case 2 74F | II | 32% | 36% | + |

| III | 81% | 66% | ++ | |

| V | 80% | 60% | +++ | |

| VI | 58% | 41% | ++++ | |

| Case 4 59M | II | 42% | 19% | + |

| III | 66% | 78% | + | |

| V | 50% | 45% | + | |

| VI | 55% | 47% | ++ |

While there is overall good concordance, some variability is obvious. For case 6, this is exceptionally large, possibly due to the longer PMI (30 hrs. vs. <24) and/or the demographics of the individual (case history; younger age). For this case, both the OCM imaging and the Nissl histology were problematic, compromising both the segmentation and the registration. Relative to our five other cases, case 6 presented as an outlier. Since results for case 6 skewed the percentage averages for B32, we opted to exclude data from this case for the remaining sections of the paper, however we will also show the data including this case without discussing them.

Quantitative results for BA 21.

For BA 21, the percentage of OCM neurons colocalizing with Nissl stained neurons was 42% ± 15 % in layer II, 74% ± 9% in layer III, 64% ± 15% in layer V, and 60% ± 6% in layer VI. The equivalent colocalization percentages calculated for Nissl neurons were slightly less; namely, 33% ± 13% in layer II, 74% ± 12% in layer III, 55% ± 13% in layer V, and 45% ± 7% in layer VI. This is likely due to our stringent labeling criteria, which affected the number of OCM neurons more than Nissl stained neurons. The colocalization data are summarized in Table 4, displayed for each layer, and as an average for all layers. Across the three cases and four layers in BA 21, the OCM and Nissl colocalization percentage averaged 60% and 52%, respectively.

Table 4 –

The averages of the colocalization percentages for each layer in BA21.

| Table 4 - BA21 | OCM % | Nissl % |

|---|---|---|

| Layer II | 42 ± 15 | 33 ± 13 |

| Layer III | 74 ± 9 | 74 ± 12 |

| Layer V | 64 ± 15 | 55 ± 13 |

| Layer VI | 60 ± 6 | 45 ± 7 |

| All layers | 60 ± 16 | 52 ± 18 |

Quantitative results for BA 32.

The colocalization match of OCM neurons in BA32 was 63% ± 9% in layer II, 64% ± 5% in layer III, 72% ± 17% in layer V and 71% ± 11% in layer VI (Table 5). The equivalent colocalization data calculated for Nissl neurons were 38% ± 13% in layer II, 49% ± 14% in layer III, 54% ± 16% in layer V and 45% ± 14% in layer VI. Across the three cases and four layers in BA 32, the OCM and Nissl colocalization percentage averaged 67% and 47% respectively (Table 5).

Table 5 –

The averages of the colocalization percentages for each layer in BA32, using all 3 case and excluding case 6 (outlier).

| Using all 3 cases | Excluding case 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Table 5 - BA 32 | OCM % | Nissl % | OCM % | Nissl % |

| Layer II | 58 ± 18 | 33 ± 12 | 63 ± 9 | 38 ± 13 |

| Layer III | 55 ± 15 | 45 ± 12 | 64 ± 5 | 49 ± 14 |

| Layer V | 60 ± 22 | 48 ± 16 | 72 ± 17 | 54 ± 16 |

| Layer VI | 57 ± 23 | 38 ± 16 | 71 ± 11 | 45 ± 14 |

| All layers | 58 ± 18 | 41 ± 15 | 67 ± 11 | 47 ± 14 |

Results for fiber content

OCM imaging is consistent with published reports that BA 21 is more densely myelinated than BA 32 (see Tables 2 and 3). In BA 32, individual fibers can be observed, even in deeper layers V and VI. In contrast, bundled fibers are more prevalent in those layers in BA 21. Deeper layers are more densely myelinated than the superficial layers I and II. The results are shown is Table 6. For the fiber grade (+), defined as some individual and sparse fibers, the OCM colocalization is the poorest; namely 55% ± 14% (44% ± 18% for Nissl). The OCM colocalizations rise to 71% ± 13% and 78% ± 9%, respectively, for “individual but dense” fibers (++) and “large sparse” bundle (+++). [The corresponding Nissl matches are 51% ± 14% and 70% ± 19%. Finally, the OCM colocalization drops to 61% ± 4% for “large and dense” fiber bundles (51% ± 10% for Nissl).

Table 3 –

Colocalization percentages for each case, block and layer in BA32.

| Table 3 – BA 32 | Layer | OCM % | Nissl % | Fiber content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 3 68M | II | 62% | 30% | + |

| III | 68% | 41% | + | |

| V | 75% | 41% | ++ | |

| VI | 80% | 38% | ++ | |

| Case 5 58M | II | 64% | 46% | + |

| III | 61% | 58% | + | |

| V | 69% | 68% | ++ | |

| VI | 61% | 53% | ++ | |

| Case 6 30F | II | 48% | 24% | + |

| III | 37% | 38% | + | |

| V | 38% | 36% | + | |

| VI | 31% | 23% | + |

Table 6 –

Colocalization percentages with respect to fiber content, using all cases and excluding case 6 (outlier).

| All cases | Excluding case 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Table 6 - Fiber content | OCM % | Nissl % | OCM % | Nissl % |

| + (n=18) | 50 ± 15 | 40 ± 17 | 55 ± 14 | 44 ± 18 |

| ++ (n=12) | 71 ± 13 | 51 ± 14 | 71 ± 13 | 51 ± 14 |

| +++ (n=4) | 78 ± 9 | 70 ± 19 | 78 ± 9 | 70 ± 19 |

| ++++ (n=6) | 61 ± 4 | 51 ± 10 | 61 ± 4 | 51 ± 10 |

n= the number of ROIs in each group

In summary, we consider that neuronal size (large versus small neurons), the amount of myelination (robust or sparse), and the orientation and density of dendrites will impact on the sensitivity and resolution of OCM. This is discussed more fully below (“Human Neuroanatomy”).

DISCUSSION

With this report, we now have colocalization data for three cortical areas. The overall average colocalization in OCM compared to the Nissl stained tissue, was 67% for BA 32 (47% Nissl colocalization), and 60% for BA 21 (52% Nissl colocalization). In our previous paper (Magnain et al., 2015), we found a OCM colocalization of 78% for layer II of entorhinal cortex. The appropriate comparison in our samples for layer II of EC is not the very different layer II of BA 21 or BA 32. Extracting the criteria of large cells and sparse myelin, a reasonable comparison is with layer III of BA 21 and layer V of BA 32. In that case, the match numbers across the three areas are in relatively good concordance; that is, 78% for EC, 74% for BA21, layer III, and 71% for BA 32, layer V (excluding case 6). From this still limited dataset, our provisional conclusion is that the successful match level between neuronal OCM and Nissl will differ across areas and layers. Below, we further discuss the results and the various factors likely to influence the concordance between OCM and Nissl. These can be divided into two categories: factors related to technical challenges and those related to anatomy, especially of the human brain.

Technical issues

In the course of these investigations, we have identified and addressed important technical factors that can influence the quality of outcome. One obvious technical factor influencing the concordance of optical and histological datasets is the mismatch in the acquisition range between the two modalities. First, unless the movement of the stage precisely and consistently advances by 50 μm increments per vibratome section, the Nissl stained slices may be either thicker or thinner than the optical imaging depth range. Discrepancies of this nature can be corrected by manually inspecting the colocalization with respect to depth as shown in Figure 3. Second, the initial focus depth must be carefully set to insure the capture of the top of 50 μm tissue section. The z pixel size is 2.9 μm and we need to focus, by eye, at 5 μm under the surface; that is, less than 2 pixels under the surface. The determination of the first focus plane of the acquisition is not absolutely precise; for example, the tissue surface boundary and the focus plane are not a clear line. To control for this, each focus depth was determined post-acquisition. If the first depth showed variability, we took notice that for some tissue samples, the focus plane was too deep, meaning that the first few microns were not optically imaged. Occurrences of erroneous neuronal colocalization in depth happened but these were rare.

A second potential technical source of error occurs at the registration step between the OCM and the Nissl stained sections. The first registration (the pre-registration) between the full slice of the histology and the OCM image is relatively routine and evaluating the accuracy is easy because it is the exact same block (same corners, same blood vessels). The second registration, the registration of each ROI, was also straightforward, as above, but it becomes critical to inspect and evaluate the accuracy. This second registration was performed on a much smaller region with different criterion - groupings of three or four distinct neurons in multiple places. The accuracy of the registration requires special care on the part of the evaluator, so that the registration makes sense with the structures within the ROI. Ideally the process can be automatized to reduce time and enable a larger sample size. Our procedure has been manual, where we used tissue corners for the first registration, but neurons for the aligning landmarks for the second registration. An accurate registration is time consuming but can be satisfactorily assessed with unique groups of neurons that are distinct within the ROI.

Third is the segmentation of the OCM data. In this present study, we took the opportunity to reexamine our previous criteria, and adopted strict, multiple corroborating criteria for the OCM neuronal segmentation. A major factor in neuronal segmentation is image degradation from speckle noise. Frequency compounding achieved partial but not total noise (Magnain, Wang, Sakadžić, Fischl, & Boas, 2016; Pircher, Gotzinger, Leitgeb, Fercher, & Hitzenberger, 2003; Schmitt, Xiang, & Yung, 1999; Van Soest et al., 2012). Segmentation was thus affected by imperfect contrast between neurons and the surrounding environment. Noise reduction techniques will be important to consider and undertake in continued development of OCM. Namely, noise reduction by spatial compounding (i.e. due to the overlapping during data acquisition between adjacent tiles) has not been exploited. In addition, spatial filtering could be applied to the data, which will lead to a loss of resolution but will improve contrast. Thus, evaluating and optimizing the tradeoffs among acquisition time, contrast and resolution may be central to improving for neuronal segmentation in OCM. Lastly, using 3D imaging reconstruction and the volumetric shape as additional marker for neurons may enhance segmentation. In the longer term, we hope that our experience with technical details of manual segmentation will be applicable to automatic segmentation where training datasets can be implemented, with respect to parameters of neuronal size and shape- Future studies could re-evaluate additional biological structures such as fiber bundles that were not labeled but might have detrimentally interfered with the neuronal standards set forth in this report.

Human Neuroanatomy

Studying the human brain, more than for experimental animal models, is associated with special problems of inherent individual variability, variability of health or pathologies, and cross- and intra-areal variability. Of direct practical relevance in the present study, only one of the brains (case #1) was from our previous study in the entorhinal cortex (Magnain et al. 2015). The influence of age will be an important factor for continued investigation, but we can point out that the oldest cases in this current study, cases #2 and #3, have the best colocalization, >80%.

While all the cases included in this study were technically controls from both a clinical and pathological perspective, some age-related neurofibrillary tangles were present in the entorhinal and perirhinal cortices in cases #3, 4 and 5. These could indicate an underlying preclinical condition that may degrade OCM performance accuracy. Amyloid was not observed in these cases even though amyloid plaques have been visualized using OCM (Lichtenegger et al. 2017) and with polarized light imaging (Baumann et al. 2017). It is not presently known whether the presence of neurofibrillary tangles, lipofuscin or reactive gliosis may adversely affect OCM accuracy.

Other anatomical factors may influence OCM performance. These can be of a mechanical nature; namely, the basic geometry of the human brain, the constantly changing cortical ribbon and its interaction with the plane of sectioning, and the specific location within a gyrus (crown or sulcal depth). Another significant anatomical factor is heterogeneity in the structural make-up and microenvironment of the different areas. This includes but is not limited to neuronal size (large versus small neurons), the amount of myelination (robust or sparse), the orientation and density of dendrites. Our data show that the colocalization is lower for layer II compared to layers III, V and VI for both BA 21 and 32 (respectively 42% ± 15% and 63% ± 9% for OCM, and 33% ± 13% and 38% ± 13% for Nissl). The smaller neurons in layer II are harder for the OCM to image and for the raters to segment. The small size might confound by being too close to the size of the speckle noise inherent to OCM imaging. Moreover, our data suggest that the myelin density and fiber orientation in particular influence the success of OCM-Nissl colocalization. Dense fiber fascicles (++++) appear to “shroud” or “veil” neurons, perhaps due to the size of individual fibers or fascicles, or the proportion of myelinated and unmyelinated fibers. In accord, we found an OCM colocalization of 61% ± 4% (51% ± 10% for Nissl), compared to an OCM colocalization better than 70% for fiber densities of ++ and +++. The category of sparse individual fibers (+) shows the lowest colocalization, 55% ± 14% for OCM and 44% ± 18% for Nissl; but we note that 10 out of the 18 boxes analyzed for this category are located in layer II, the zone of small neurons. When removing the results obtained for layer II, the colocalization for sparse fibers (+) increases to 61% ± 9% and 55% ± 17% for OCM and Nissl, respectively, and is on par with the higher myelination density (++++). Thus, our data also suggests that neuron size influences the colocalization of OCM and Nissl. It is our current understanding that more than one factor contributes to the variability of visualizing OCM neurons, with fiber quantity and neuronal size being the most impactful.

The microanatomical environment is intricate, and other confounding factors will need to be investigated in continuing methodological investigations. For example, in this study, we did not correlate success of match with the neuronal density or extracellular space surrounding neurons; but these parameters could all be further explored.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a number of procedural details, which we have tried to set forth here, will affect the outcome quality of OCM as applied to human postmortem cortical samples. These notably include 1) pathological state of the tissue, 2) macro anatomical and laminar location, 3) location and depth in the imaged stack and 4) the imaging noise. Taking these into account, OCM is a promising tool that can demonstrate detail at the neuron level and, as semi high through-put, could help in assessing individual variability. The potential to reconstruct the cytoarchitecture in three dimensions at high resolution (approximately 1×1×2.9 μm3) and concurrently compare this with fibers and blood vessels would result in an enriched neuropathological dataset. On the down side, OCM generates large amounts of data, for which powerful computing capacity is needed. Looking ahead, for large samples, post-processing of the volumetric data can be performed (speckle noise reduction and extraction of the focus range) on the fly or in parallel to the acquisition, which would greatly reduce the data size by about a factor of at least 100. A second limitation, under current protocols, is that it is relatively slow. That is, our OCT/OCM system uses a 46k line per second (lps) line scan camera. The acquisition time could be reduced by using a faster line scan camera and/or with parallel imaging or using a swept-source OCT instead of a spectral domain OCT (An, Li, Shen, & Wang, 2011; Lee et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2018; Potsaid et al., 2008; Tsai et al., 2013). Finally, the amount of time spent manually labeling neurons could eventually be reduced and even replaced by the development of automatic segmentation algorithms to distinguish and register the individual neurons. Optical imaging, at both the OCT and OCM levels of resolution, can already be successfully applied at neuroanatomical level quality and, especially with the continued development of both the hardware and analysis programs described previously and currently underway (automatic segmentation and registration, assessment of optical properties (Wang 2017)), it has distinct potential to automatically acquire large datasets for the human brain.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the brain donors for their generous gift, Samantha Romano for help with histology and segmentation and Dr. Ender Konukoglu for the interaction non-linear registration tool.

Funding: We thank National Institutes of Health (NIH) for funding support: National Institute of Mental Health (MH107456), National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (P41EB015896, 1R01EB023281, R01EB006758, R21EB018907, R01EB019956), the National Institute on Aging (5R01AG008122, R01AG016495), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1-R21-DK-108277–01), the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS0525851, R21NS072652, R01NS070963, R01NS083534, 5U01NS086625), and was made possible by the resources provided by Shared Instrumentation Grants 1S10RR023401, 1S10RR019307, and 1S10RR023043. Additional support was provided by the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (5U01-MH093765), part of the multi-institutional Human Connectome Project.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: BF has a financial interest in CorticoMetrics, a company whose medical pursuits focus on brain imaging and measurement technologies. BF’s interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

No human participants or animals were used in this study. This study involved only de-identified post-mortem human tissue.

REFERENCES

- Amunts K, Lepage C, Borgeat L, Mohlberg H, Dickscheid T, Rousseau ME, Bludau S, Bazin PL, Lewis LB, Oros-Peusquens AM, Shah NJ, Lippert T, Zilles K, Evans AC (2013) BigBrain: an ultrahigh-resolution 3D human brain model. Science 340 (6139):1472–1475. doi: 10.1126/science.1235381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J (2012) SPM: a history. Neuroimage 62 (2):791–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assayag O, Grieve K, Devaux B, Harms F, Pallud J, Chretien F, Boccara C, Varlet P (2013) Imaging of non-tumorous and tumorous human brain tissues with full-field optical coherence tomography. Neuroimage Clin 2:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axer M, Strohmer S, Grassel D, Bucker O, Dohmen M, Reckfort J, Zilles K, Amunts K (2016) Estimating Fiber Orientation Distribution Functions in 3D-Polarized Light Imaging. Front Neuroanat 10:40. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2016.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann B, Woehrer A, Ricken G, Augustin M, Mitter C, Pircher M, Kovacs GG, Hitzenberger CK (2017) Visualization of neuritic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease by polarization-sensitive optical coherence microscopy. Sci Rep 7:43477. doi: 10.1038/srep43477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL (1989) Principal warps: thin-plate splines and the decomposition of deformations. Principal warps: thin-plate splines and the decomposition of deformations 11 (6):567–585. doi: 10.1109/34.24792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82 (4):239–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K (1909) Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrinde. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig [Google Scholar]

- Chung K, Wallace J, Kim SY, Kalyanasundaram S, Andalman AS, Davidson TJ, Mirzabekov JJ, Zalocusky KA, Mattis J, Denisin AK, Pak S, Bernstein H, Ramakrishnan C, Grosenick L, Gradinaru V, Deisseroth K (2013) Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 497 (7449):332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupe P, Catheline G, Lanuza E, Manjon JV (2017) Towards a unified analysis of brain maturation and aging across the entire lifespan: A MRI analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 38 (11):5501–5518. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da X, Toledo JB, Zee J, Wolk DA, Xie SX, Ou Y, Shacklett A, Parmpi P, Shaw L, Trojanowski JQ, Davatzikos C (2014) Integration and relative value of biomarkers for prediction of MCI to AD progression: spatial patterns of brain atrophy, cognitive scores, APOE genotype and CSF biomarkers. Neuroimage Clin 4:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta G, Colasanti A, Rabiner EA, Gunn RN, Malik O, Ciccarelli O, Nicholas R, Van Vlierberghe E, Van Hecke W, Searle G, Santos-Ribeiro A, Matthews PM (2017) Neuroinflammation and its relationship to changes in brain volume and white matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Brain 140 (11):2927–2938. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding SL, Royall JJ, Sunkin SM, Ng L, Facer BA, Lesnar P, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, McMurray B, Szafer A, Dolbeare TA, Stevens A, Tirrell L, Benner T, Caldejon S, Dalley RA, Dee N, Lau C, Nyhus J, Reding M, Riley ZL, Sandman D, Shen E, van der Kouwe A, Varjabedian A, Write M, Zollei L, Dang C, Knowles JA, Koch C, Phillips JW, Sestan N, Wohnoutka P, Zielke HR, Hohmann JG, Jones AR, Bernard A, Hawrylycz MJ, Hof PR, Fischl B, Lein ES (2016) Comprehensive cellular-resolution atlas of the adult human brain. J Comp Neurol 524 (16):3127–3481. doi: 10.1002/cne.24080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economo C, Koskinas GN (1925) Die Cytoarchitektonik der Hirnrinde des erwachsenen Menschen.

- Falahati F, Ferreira D, Muehlboeck JS, Eriksdotter M, Simmons A, Wahlund LO, Westman E (2017) Monitoring disease progression in mild cognitive impairment: Associations between atrophy patterns, cognition, APOE and amyloid. Neuroimage Clin 16:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B (2012) FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62 (2):774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, van der Kouwe AJ, Makris N, Segonne F, Quinn BT, Dale AM (2004) Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. Neuroimage 23 Suppl 1:S69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Warner TA, Jays PR, Bacon SJ (2003) Areal and synaptic interconnectivity of prelimbic (area 32), infralimbic (area 25) and insular cortices in the rat. Brain Res 993 (1–2):59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, Hee MR, Flotte T, Gregory K, Puliafito CA, et al. (1991) Optical coherence tomography. Science 254 (5035):1178–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM (2012) Fsl. Neuroimage 62 (2):782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenegger A, Harper DJ, Augustin M, Eugui P, Muck M, Gesperger J, Hitzenberger CK, Woehrer A, Baumann B (2017) Spectroscopic imaging with spectral domain visible light optical coherence microscopy in Alzheimer’s disease brain samples. Biomed Opt Express 8 (9):4007–4025. doi: 10.1364/BOE.8.004007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnain C, Augustinack JC, Konukoglu E, Frosch MP, Sakadzic S, Varjabedian A, Garcia N, Wedeen VJ, Boas DA, Fischl B (2015) Optical coherence tomography visualizes neurons in human entorhinal cortex. Neurophotonics 2 (1):015004. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.2.1.015004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnain C, Augustinack JC, Reuter M, Wachinger C, Frosch MP, Ragan T, Akkin T, Wedeen VJ, Boas DA, Fischl B (2014) Blockface histology with optical coherence tomography: a comparison with Nissl staining. Neuroimage 84:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnain C, Wang H, Sakadzic S, Fischl B, Boas DA (2016) En face speckle reduction in optical coherence microscopy by frequency compounding. Opt Lett 41 (9):1925–1928. doi: 10.1364/OL.41.001925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai JK, Paxinos G (2007) The Human Nervous System. Third Ed. edn,

- Palomero-Gallagher N, Mohlberg H, Zilles K, Vogt B (2008) Cytology and receptor architecture of human anterior cingulate cortex. J Comp Neurol 508 (6):906–926. doi: 10.1002/cne.21684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomero-Gallagher N, Zilles K, Schleicher A, Vogt BA (2013) Cyto- and receptor architecture of area 32 in human and macaque brains. J Comp Neurol 521 (14):3272–3286. doi: 10.1002/cne.23346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P (2009) Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics 25 (11):1463–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragan T, Kadiri LR, Venkataraju KU, Bahlmann K, Sutin J, Taranda J, Arganda-Carreras I, Kim Y, Seung HS, Osten P (2012) Serial two-photon tomography for automated ex vivo mouse brain imaging. Nat Methods 9 (3):255–258. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B (2012) Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage 61 (4):1402–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Greve DN, Desikan RS, Busa E, Morris JC, Dale AM, Fischl B (2004) Thinning of the cerebral cortex in aging. Cereb Cortex 14 (7):721–730. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan VJ, Radhakrishnan H, Jiang JY, Barry S, Cable AE (2012) Optical coherence microscopy for deep tissue imaging of the cerebral cortex with intrinsic contrast. Opt Express 20 (3):2220–2239. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.002220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R, Ye L, Hsueh B, Deisseroth K (2014) Advanced CLARITY for rapid and high-resolution imaging of intact tissues. Nat Protoc 9 (7):1682–1697. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC (2012) Cortical cartography and Caret software. Neuroimage 62 (2):757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Hof PR, Zilles K, Vogt LJ, Herold C, Palomero-Gallagher N (2013) Cingulate area 32 homologies in mouse, rat, macaque and human: cytoarchitecture and receptor architecture. J Comp Neurol 521 (18):4189–4204. doi: 10.1002/cne.23409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Akkin T, Magnain C, Wang R, Dubb J, Kostis WJ, Yaseen MA, Cramer A, Sakadzic S, Boas D (2016) Polarization sensitive optical coherence microscopy for brain imaging. Opt Lett 41 (10):2213–2216. doi: 10.1364/OL.41.002213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Magnain C, Wang R, Dubb J, Varjabedian A, Tirrell LS, Stevens A, Augustinack JC, Konukoglu E, Aganj I, Frosch MP, Schmahmann JD, Fischl B, Boas DA (2017) as-PSOCT: Volumetric microscopic imaging of human brain architecture and connectivity. Neuroimage 165:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Magnain C, Sakadžić S, Fischl B, Boas DA (2017) Characterizing the optical properties of human brain tissue with high numerical aperture optical coherence tomography Biomed Opt Express in press (accepted November 8, 2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhu J, Reuter M, Vinke LN, Yendiki A, Boas DA, Fischl B, Akkin T (2014) Cross-validation of serial optical coherence scanning and diffusion tensor imaging: a study on neural fiber maps in human medulla oblongata. Neuroimage 100:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo TS, Ackerman MJ, Lorensen WE, Schroeder W, Chalana V, Aylward S, Metaxas D, Whitaker R (2002) Engineering and algorithm design for an image processing Api: a technical report on ITK--the Insight Toolkit. Stud Health Technol Inform 85:586–592 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]