Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative disease that induces symptoms such as a decrease in motor function and cognitive impairment. Increases in the aggregation and deposition of amyloid beta protein (Aβ) in the brain may be closely correlated with the development of Alzheimer's disease. In this study, the effects of an adzuki bean extract on the aggregation of Aβ were examined; moreover, the anti-Alzheimer's activity of the adzuki extract was examined.

MATERIALS/METHODS

First, we undertook thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence analysis and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to evaluate the effect of an adzuki bean extract on Aβ42 aggregation. To evaluate the effects of the adzuki extract on the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease in vivo, Aβ42-overexpressing Drosophila were used. In these flies, overexpression of Aβ42 induced the formation of Aβ42 aggregates in the brain, decreased motor function, and resulted in cognitive impairment.

RESULTS

Based on the results obtained by ThT fluorescence assays and TEM, the adzuki bean extract inhibited the formation of Aβ42 aggregates in a concentration-dependent manner. When Aβ42-overexpressing flies were fed regular medium containing adzuki extract, the Aβ42 level in the brain was significantly lower than that in the group fed regular medium only. Furthermore, suppression of the decrease in motor function, suppression of cognitive impairment, and improvement in lifespan were observed in Aβ42-overexpressing flies fed regular medium with adzuki extract.

CONCLUSIONS

The results reveal the delaying effects of an adzuki bean extract on the progression of Alzheimer's disease and provide useful information for identifying novel prevention treatments for Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Adzuki bean, alzheimer disease, amyloid beta, drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease is an irreversible progressive neurodegenerative disease. Symptoms of the disease include decreases in verbal ability and motor function and cognitive impairment [1]. The main pathological features of Alzheimer's disease are senile plaque formation due to the aggregation of amyloid beta protein (Aβ). The longer Aβ species, such as Aβ42 species ending at Ala42, are highly amyloidogenic and deposit more frequently than Aβ40 species ending at Val40 in the brain of Alzheimer's disease patients. A series of events in which Aβ42 is converted from amyloid precursor protein, which is a precursor of Aβ42, can result in Aβ42 abnormally aggregating into oligomers and fibrils. Synaptic dysfunction, tau protein hyperphosphorylation and aggregation, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress can follow, leading eventually to neuronal death and the progression of cognitive impairments [2,3]. However, no effective treatments have been established for Alzheimer's disease. Given the rapidly increasing incidence of patients with Alzheimer's disease, new drugs to treat or cure the disease are needed.

It is widely reported that plant-derived components contain active ingredients that are effective for treating various diseases. For example, plant extracts have been shown to have hypoglycemic [4], antioxidant [5], and anti-inflammatory [6] properties. In addition, there are studies that have shown that some plant extracts possess potential anti-Alzheimer's properties. For example, garlic extract reduces Aβ42 levels in the brains of TgCRND8 mice, leading to the suppression of learning and memory disorders [7]. Cinnamon extract is known to inhibit Aβ aggregation in the brain of Aβ42-overexpressing flies, leading to improvement in motor function and lifespan; moreover, cinnamon extract suppresses Aβ deposition in the brains of 5XFAD mice, leading to improvement in memory disorders [8]. Plant extracts may thus have significant potential to treat Alzheimer's disease. However, few studies have explored this potential.

The adzuki bean (Vigna angularis) is a leguminous plant used in folk medicine and traditional snacks in East Asia including Japan, Korea, and China. Adzuki beans contain dietary fiber, saponins, and polyphenols. Moreover, adzuki bean is reported to possess anti-oxidant [9], anti-inflammatory [10], anti-hypertensive [11], and anti-diabetic properties [9,12]. Despite the many reported properties of adzuki bean, no study has evaluated its potential to treat Alzheimer's disease. Therefore, we studied the effect of an adzuki bean extract on Aβ42 aggregation in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease.

As the lifespan of Drosophila is short, it is a useful experimental animal for studying age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease [13]. In recent years, Drosophila has been frequently used as a model is Alzheimer's disease studies [14,15,16]. In the present study, we used the GAL4-UAS system to produce transgenic flies that overexpress human Aβ42 in the brain. These transgenic flies reportedly exhibit age-related motor function disorders, memory disorders, and an abnormal lifespan, as well as neurodegeneration associated with Aβ aggregation [15]. In this study, we investigated the ability of an adzuki bean extract to inhibit Aβ aggregation in vitro and to alleviate motor function disorders, memory disorders, and an abnormal lifespan in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adzuki extract

Red adzuki beans (500 g) harvested in Tokachi, Hokkaido, Japan, were immersed in distilled deionized (dd) water (2 L) at room temperature overnight, and then the mixture was filtrated through cotton. After discarding the water, a 40% ethanol solution (4 L) was added to the red beans and the mixture allowed to stand at room temperature for 36 hours. After filtration of the ethanol extract with cotton, it was concentrated in vacuo at 45℃ to yield the concentrate (22 g). The obtained ethanol adzuki bean extract was stored at −20℃ for further use.

Preparation of Aβ solution

The Aβ solution was prepared according to the method in a previous report [17]. Briefly, synthetic Aβ1-42 (PEPTIDE INSTITUTE, Osaka, Japan) was dissolved in 0.1% ammonia solution at a final concentration of 250 µM and sonicated in ice-cold water for a total of 5 min (1 min × 5 times) to avoid pre-aggregation. For preparation of the Aβ solution, aliquots of Aβ were diluted to 25 µM in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl.

Thioflavin T fluorescence assay

The thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay was performed as previously described [18]. Aβ solution (8 µL) was mixed with the adzuki extract and the mixture then added to 1.6 mL of ThT solution containing 5 µM ThT and 50 mM NaOH- glycine-buffer (pH 8.5). The final concentration of the adzuki extract in the mixture ranged from 0 to 1 mg/mL. The samples were incubated at 37℃ and the fibrillogenesis rate was monitored by using ThT fluorescence assays. The samples ThT fluorescence levels were evaluated by using an FP-6200 spectrofluorometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). The respective excitation and emission wavelengths were 446 nm and 490 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy

Analysis of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results was performed as previously described [18]. The Aβ solution was incubated with or without Adzuki at 37℃ for 24 h. The final concentration of the adzuki extract was ranged from 0 to 1 mg/mL. Aliquots (10 µL) from the samples were placed on 200 mesh copper grids (Nisshin EM., Tokyo, Japan) for 5 min, after which, excess fluid was removed, and the grids stained with 10 µL of TI blue (Nisshin EM) for 5 min. TI blue is an alternative to uranyl acetate for TEM staining. Again, the excess fluid was removed and the grids dried. The prepared samples were examined with a JEM-1400 microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

Fly stocks and culture

A UAS/GAL4 system was utilized for inducing transgene expression. The elav-GAL4 driver (Bloomington Drosophila stock center, IN, USA) was used to express transgenes in the brain starting early during development. The UAS transgene was human Aβ42 (a generous gift from Dr. Koichi Iijima, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Japan). Flies were kept at 25℃. Adzuki extract dissolved in ddH2O was added to the standard cornmeal-molasses medium (1 mg/mL) and the mixture incubated at 60℃ for 15 min. Crosses were performed with flies either on standard cornmeal-molasses medium (control) or on medium supplemented with adzuki extract.

ELISA analysis

Aβ42 levels were determined using Wako High Sensitive Human β Amyloid (1–42) ELISA kits (Wako, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, 20 fly heads were homogenized in 50 µL of ice-cold 1× RIPA buffer. The homogenates were diluted 10-fold with 450 µL of sample diluent and then cleared by centrifugation at 15,000 r/min for 5 min at 4℃. The supernatant (200 µL) of each sample was added to the ELISA plate.

Climbing assay

Fly climbing assays were performed as previously described [19]. Approximately 15 flies were placed in an empty 2.5 cm by 9.5 cm (diameter by height) plastic vial, gently tapped to the vial bottom, and videotaped for 18 s. The vial was separated into three areas; “top”, “middle”, and “bottom” by clear and readable lines with each are including a distance of 3 cm. The percentages of flies that climbed to the top, middle, and bottom of the test vial were calculated. There was a minimum of 6 separate climbing trials per condition.

Single-cycle training and memory assays

Standard single-cycle olfactory conditioning was performed as previously described [20]. Briefly, approximately 100 flies were trained by exposing them to two odors (3-octanol or 4-methylcyclohexanol), one of which was paired with a series of aversive electrical shocks (65 V, 1.5 s pulses every 5 s) for 1 min. For testing, flies were placed at a choice point located between the two odors for 1.5 min. Learning and memory retention were quantified as a performance index calculated by subtracting the percentage of flies that chose the shock-paired odor from the percentage that chose the unpaired odor. A performance index (PI) was calculated so that a 50:50 distribution (no memory) yielded a PI of 0 while a 0:100 distribution away from the shock-paired odor yielded a PI of 100. Individual performance indices were the average of two experiments in which the shock-paired and unpaired odor presentations were alternated.

Longevity assay

Lifespan assays were performed as described by Schriner et al. [21]. Approximately 10 flies were placed in a food vial (with or without adzuki extract) and fresh food was given every other day. Any flies that died due to food or that flew away during the study were censored from the longevity assay. Flies were checked every day during the light portion of the light:dark cycle and the total number of live flies was recorded in each vial each day. For each diet, at least 200 flies were assayed. Kaplan-Meier plots were derived, and the median survival time for each group was determined. Survival curves were compared by using a log-rank test.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was applied to determine the statistical significance of differences in the ThT assay and ELISA data. Multiple group comparisons were performed by performing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey-Kramer test to detect intergroup differences in the climbing and longevity assay data. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 Software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are expressed as Means±standard error of the mean, with at least three repeats in each experimental group. Test results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of adzuki extract on in vitro Aβ42 aggregation

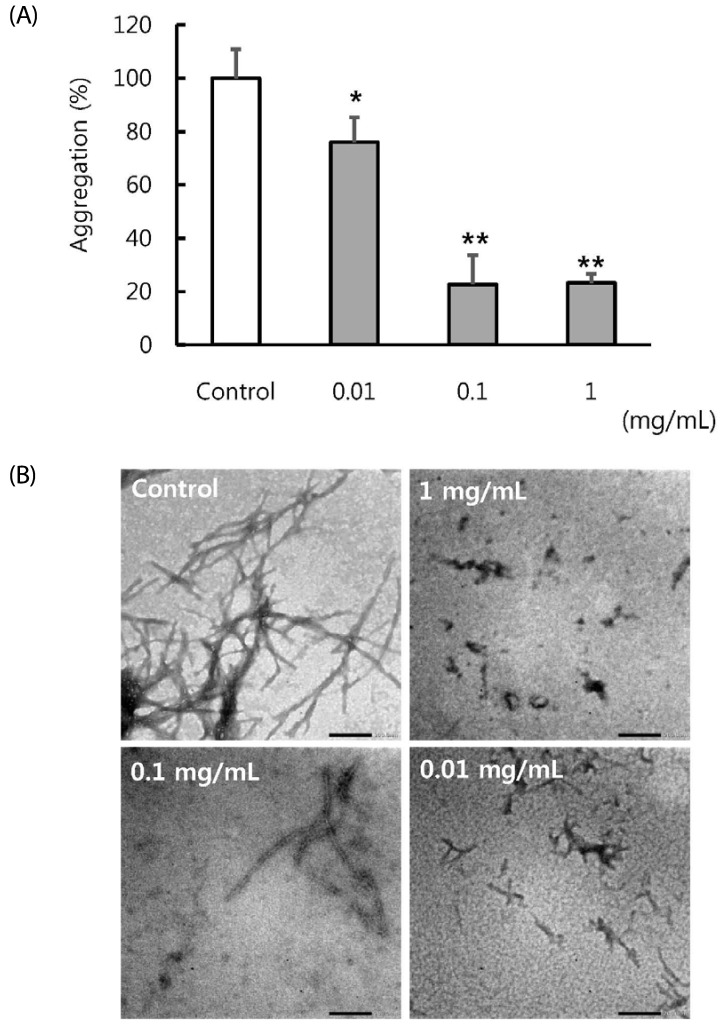

First, we conducted ThT assays to evaluate the effect of the adzuki bean extract on Aβ42 aggregation. Setting the fluorescence of samples containing only Aβ42 at 100%, the relative fluorescence of samples containing Aβ42 and 1 mg/mL or 0.1 mg/mL of adzuki extract were both approximately 20% while the relative fluorescence of samples containing Aβ42 and 0.01 mg/mL of adzuki extract was 75% (Fig. 1A). Next, the effect of adzuki extract on Aβ42 aggregate formation was evaluated by TEM. While the fibrils formed by Aβ42 alone were abundant, large, and broadly ribbon-like, the fibrils formed by Aβ42 in the presence of adzuki extract (0.01–1 mg/mL) were less abundant and of a smaller diameter and length (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that the adzuki extract suppresses Aβ42 aggregate formation in a concentration-dependent manner.

Fig. 1. Effect of adzuki bean extract on in vitro Aβ42 aggregation.

(A) The Aβ42 solution was incubated at 37℃ for 24 h in the absence (white bar) or presence (black bar) of various concentrations of the adzuki extract (0.01–1 mg/mL). The samples were evaluated by examining ThT fluorescence. Emission wavelength was monitored at 490 nm and excitation at 446 nm. The results are expressed as Means±SEM for three independent determinations. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 compared with the control, n = 3. (B) TEM results; the Aβ42 solution was incubated at 37℃ for 24 h in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of the adzuki extract. In each case, the scale bar represents 200 nm.

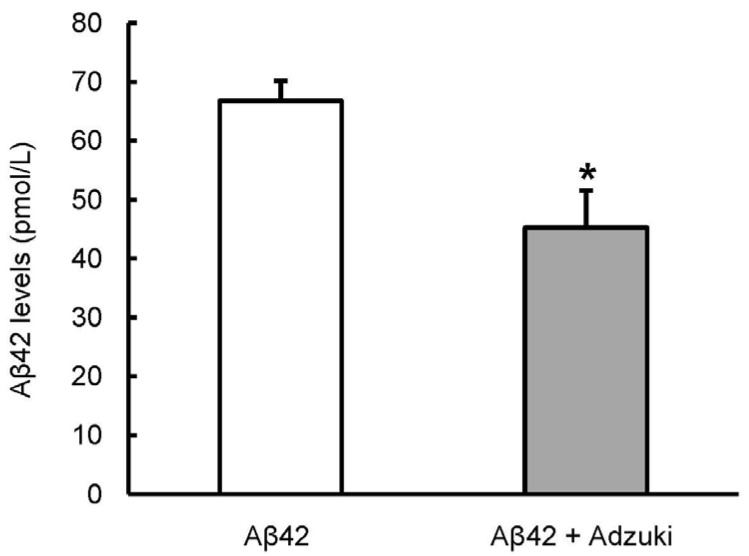

Intake of adzuki extract reduces the Aβ42 level in the brain of Aβ42-overexpressing flies

Aβ42-overexpressing flies were used to evaluate in vivo the effect of the adzuki extract on the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. As a first step, the Aβ42 level in fly brain was determined by using ELISA. The Aβ42 level was significantly lower in the group fed the regular medium containing adzuki extract than in the group fed only the regular medium (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Intake of adzuki bean extract reduces the Aβ42 levels in the brain of Aβ42-overexpressing flies.

Aβ42-overexpressing flies were grown on regular medium (Aβ42) or medium containing adzuki extract (Aβ42+Adzuki). At 15 days old, Aβ42 levels in fly head lysates were quantified by ELISA. Results are expressed as Means±SEM for three independent determinations. * P < 0.05 compared with Aβ42 (grown on regular medium) n = 60.

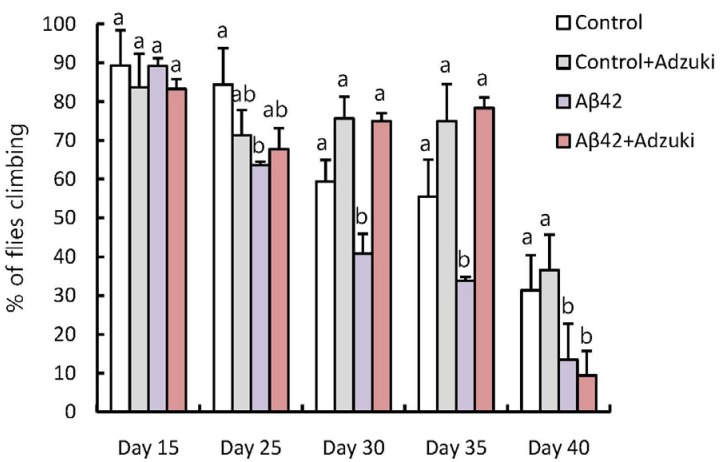

Intake of adzuki extract increases the locomotor activity of Aβ42-overexpressing flies

Next, to evaluate the effect of the adzuki extract on motor function in Aβ42-overexpressing flies, we used climbing assays. In the fly group fed the regular medium, approximately 10% of 15-day-old flies, 40% of 25-day-old flies, and 70% of 30-day-old flies showed decreases in motor function (Fig. 3). However, in the group fed the regular medium containing adzuki extract, only 30% of flies showed a decrease in motor function at 30 and 35 days of age. These results indicated that the intake of adzuki extract delayed the decrease in motor function in Aβ42 flies.

Fig. 3. Intake of adzuki bean extract increases the locomotor activity of Aβ42-overexpressing flies.

Control flies (carrying the Aβ42 transgene but not expressing it) were grown on regular medium (control) or on medium containing adzuki extract (Control+Adzuki), and Aβ42-overexpressing flies were grown on regular medium (Aβ42) or medium containing adzuki extract (Aβ42+Adzuki). All fly groups underwent climbing assays in the indicated days after eclosion. Results show the percentage of flies climbing to the top of the vial after 18 seconds. The results are expressed as Means±SEM for three independent determinations. Means with different letters are significantly different, P < 0.05, whereas means with similar letters are not different from each other; n > 90.

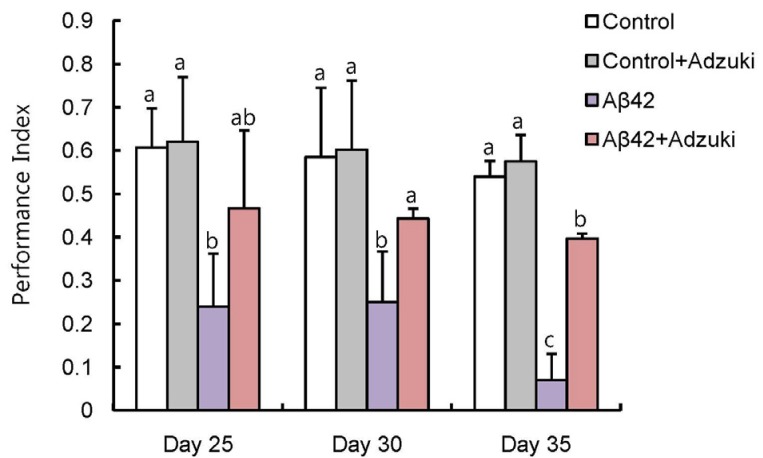

Intake of adzuki extract increases the learning and memory abilities of Aβ42-overexpressing flies

To evaluate the effect of the adzuki extract on cognitive function of flies, we used single-cycle olfactory conditioning assays. We observed a significant decrease in memory function and learning ability in Aβ42-overexpressing flies older than 25 days fed the regular medium compared to control flies (carrying the Aβ42 transgene but not expressing it) fed the regular medium; however, that decrease was suppressed in Aβ42-overexpressing flies fed the regular medium containing adzuki extract (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Intake of adzuki bean extract increases the learning and memory abilities of Aβ42-overexpressing flies.

Control flies (carrying the Aβ42 transgene but not expressing it) grown on regular medium (Control) or medium containing adzuki extract (Control+Adzuki) and Aβ42-overexpressing flies grown on regular medium (Aβ42) or medium containing adzuki extract (Aβ42+Adzuki) were tested using single-cycle olfactory training and memory assays in the indicated days after eclosion. The results are expressed as Means±SEM for three independent determinations. Means with different letters are significantly different, P < 0.05, whereas means with similar letters are not significantly different, n > 300.

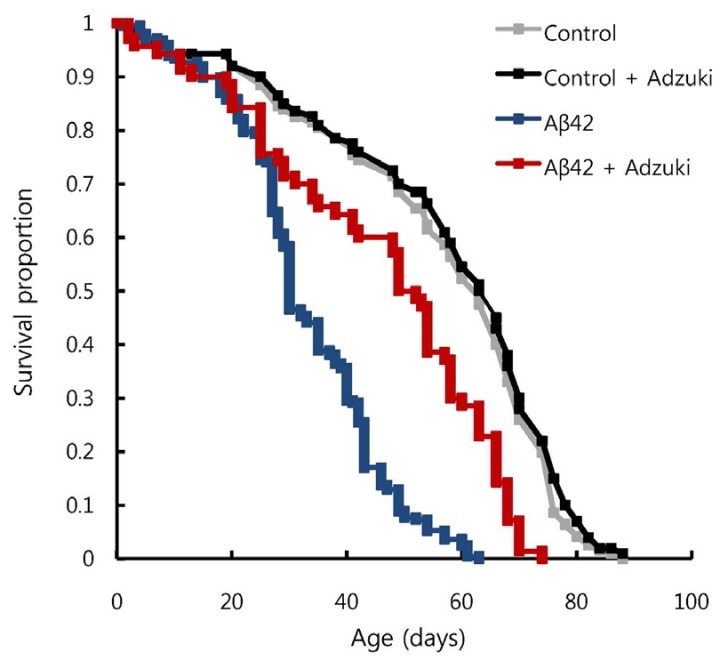

Intake of adzuki extract increases the lifespan of Aβ42-overexpressing flies

Lastly, to evaluate the effect of the adzuki extract on the lifespan of Aβ42-overexpressing flies, we used survival assays. The survival rates in the two diet groups were calculated by applying the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference was analyzed by using the log-rank test. The average life expectancy was calculated by summing the life expectancy (in days) of all individuals in a group and dividing it by the total number of individuals in that group. In the group of Aβ42-overexpressing flies fed the regular medium, a rapid decrease in survival rate was observed between 30 and 40 days of age. The survival rates of that group and the group fed the regular medium containing adzuki extract were not significantly different until day 30 of the survival assays, but from day 30 to day 50 day, the decrease in survival was more gradual in the Aβ42-overexpressing flies fed the regular medium containing adzuki extract than in those fed the regular medium only (Fig. 5). The average life expectancy was 32.8 days in the Aβ42-overexpressing flies fed the regular medium and 45.4 days in the Aβ42-overexpressing flies fed the regular medium containing adzuki extract. Thus, a greater than 10-day life expectancy increase was obtained by including adzuki extract in the diet.

Fig. 5. Intake of adzuki bean extract increases the lifespan of Aβ42-overexpressing flies.

Survival rates of control flies (carrying the Aβ42 transgene but not expressing it) grown on regular medium (Control) or medium containing adzuki extract (Control+Adzuki) and Aβ42 flies grown on regular medium (Aβ42) or medium containing adzuki extract (Aβ42+Adzuki) were analyzed using survival assays. Kaplan-Meier and log-rank analyses revealed that median survival times for Aβ42-overexpressing flies grown on regular medium and grown on medium containing adzuki extract were significantly different (32.8 days and 45.1 days, respectively, P < 0.001, n > 200).

DISCUSSION

In patients with Alzheimer's disease, it has been reported that the aggregation of Aβ42 proteins occurs during the early stages of cognitive disorders and neurodegeneration [22]. The results of the present study, which included both in vivo and in vitro experiments, indicate that the adzuki bean extract contains compounds that have anti-Alzheimer's disease effects.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports describing the efficacy of an adzuki bean extract in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. In recent years, it has been reported that extracts of the Mediterranean plants Padina pavonica and Opuntia ficus-indica can alleviate neurotoxicity due to Aβ42 and alpha-synuclein aggregates [23]. It is thought that these extracts suppress Aβ42 and alpha-synuclein aggregation and therefore protect neurons by preventing the destruction of neuronal membranes triggered by aggregation. Multiple reports have indicated that the adzuki bean contains polyphenols [11,24,25], which are reported to inhibit the aggregation of various amyloid proteins [26,27]. Although further studies are needed, it is possible that an adzuki bean extract can directly contact Aβ and suppress Aβ42 aggregation.

It has been reported that increases in the aggregation and deposition of Aβ42 in the brain are closely associated with cognitive symptoms seen in Alzheimer's disease [28]. In the present study, intake of the adzuki bean extract improved memory abnormalities observed in Aβ42-overexpressing flies. This improvement is thought to have been caused by the suppression of Aβ42 aggregation. Alternatively, oxidative stress is reported to have an important role in the onset and progression of Alzheimer's disease [29], and it has been reported that the polyphenols of adzuki beans have the ability to suppress oxidative stress [30]. Thus, the adzuki extract may have improved memory abnormalities in Aβ42-overexpressing flies by suppressing oxidative stress caused by Aβ42 proteins.

This study clearly demonstrated the anti-Alzheimer's effect of the adzuki bean extract; however, it is important to elucidate the mechanism associated with that effect in the future. Furthermore, it is unknown whether the active ingredients in the adzuki bean extract can pass through the blood-brain barrier, and this was not examined in our study. Further studies using mouse models and identifying the adzuki bean's active ingredients are needed to confirm the effects of the adzuki bean extract reported in the present study.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that an extract of adzuki bean, which is a popular food component in East Asia, may delay the progression of Alzheimer's disease. These results provide useful information that may lead to the development of novel prevention treatments for Alzheimer's disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by Mamerui kyokai Foundation (to S.Y.) and National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO): Integration research for agriculture and interdisciplinary fields (to S.Y., H.M., S.K. and H.F.).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamane T, Kozuka M, Konda D, Nakano Y, Nakagaki T, Ohkubo I, Ariga H. Improvement of blood glucose levels and obesity in mice given aronia juice by inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV and α-glucosidase. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;31:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kähkönen MP, Hopia AI, Vuorela HJ, Rauha JP, Pihlaja K, Kujala TS, Heinonen M. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:3954–3962. doi: 10.1021/jf990146l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmachari S, Jana A, Pahan K. Sodium benzoate, a metabolite of cinnamon and a food additive, reduces microglial and astroglial inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2009;183:5917–5927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chauhan NB, Sandoval J. Amelioration of early cognitive deficits by aged garlic extract in Alzheimer's transgenic mice. Phytother Res. 2007;21:629–640. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frydman-Marom A, Levin A, Farfara D, Benromano T, Scherzer-Attali R, Peled S, Vassar R, Segal D, Gazit E, Frenkel D, Ovadia M. Orally administrated cinnamon extract reduces β-amyloid oligomerization and corrects cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease animal models. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao Y, Cheng X, Wang S, Wang L, Ren G. Influence of altitudinal variation on the antioxidant and antidiabetic potential of azuki bean (Vigna angularis) Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63:117–124. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.604629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukai Y, Sato S. Polyphenol-containing azuki bean (Vigna angularis) seed coats attenuate vascular oxidative stress and inflammation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukai Y, Sato S. Polyphenol-containing azuki bean (Vigna angularis) extract attenuates blood pressure elevation and modulates nitric oxide synthase and caveolin-1 expressions in rats with hypertension. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoh T, Kobayashi M, Horio F, Furuichi Y. Hypoglycemic effect of hot-water extract of adzuki (Vigna angularis) in spontaneously diabetic KK-A(y) mice. Nutrition. 2009;25:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenz S, Karsten P, Schulz JB, Voigt A. Drosophila as a screening tool to study human neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2013;127:453–460. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittmann CW, Wszolek MF, Shulman JM, Salvaterra PM, Lewis J, Hutton M, Feany MB. Tauopathy in Drosophila: neurodegeneration without neurofibrillary tangles. Science. 2001;293:711–714. doi: 10.1126/science.1062382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iijima K, Liu HP, Chiang AS, Hearn SA, Konsolaki M, Zhong Y. Dissecting the pathological effects of human Abeta40 and Abeta42 in Drosophila: a potential model for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6623–6628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400895101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finelli A, Kelkar A, Song HJ, Yang H, Konsolaki M. A model for studying Alzheimer's Abeta42-induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama S, Ogawa H, Nakamura S. Apricot carotenoids possess potent anti-amyloidogenic activity in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:12691–12696. doi: 10.1021/jf203654c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katayama S, Sugiyama H, Kushimoto S, Uchiyama Y, Hirano M, Nakamura S. Effects of sesaminol feeding on brain Aβ accumulation in a senescence-accelerated mouse-prone 8. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:4908–4913. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen AJ, Rimkus SA, Wassarman DA. ATM kinase inhibition in glial cells activates the innate immune response and causes neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E656–E664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110470109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirano Y, Ihara K, Masuda T, Yamamoto T, Iwata I, Takahashi A, Awata H, Nakamura N, Takakura M, Suzuki Y, Horiuchi J, Okuno H, Saitoe M. Shifting transcriptional machinery is required for long-term memory maintenance and modification in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13471. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schriner SE, Kuramada S, Lopez TE, Truong S, Pham A, Jafari M. Extension of Drosophila lifespan by cinnamon through a sex-specific dependence on the insulin receptor substrate chico. Exp Gerontol. 2014;60:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selkoe DJ. Presenilin, Notch, and the genesis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11039–11041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211352598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briffa M, Ghio S, Neuner J, Gauci AJ, Cacciottolo R, Marchal C, Caruana M, Cullin C, Vassallo N, Cauchi RJ. Extracts from two ubiquitous Mediterranean plants ameliorate cellular and animal models of neurodegenerative proteinopathies. Neurosci Lett. 2017;638:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato S, Mukai Y, Yamate J, Kato J, Kurasaki M, Hatai A, Sagai M. Effect of polyphenol-containing azuki bean (Vigna angularis) extract on blood pressure elevation and macrophage infiltration in the heart and kidney of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato S, Yamate J, Hori Y, Hatai A, Nozawa M, Sagai M. Protective effect of polyphenol-containing azuki bean (Vigna angularis) seed coats on the renal cortex in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porat Y, Mazor Y, Efrat S, Gazit E. Inhibition of islet amyloid polypeptide fibril formation: a potential role for heteroaromatic interactions. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14454–14462. doi: 10.1021/bi048582a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoval H, Weiner L, Gazit E, Levy M, Pinchuk I, Lichtenberg D. Polyphenol-induced dissociation of various amyloid fibrils results in a methionine-independent formation of ROS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1570–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen QS, Kagan BL, Hirakura Y, Xie CW. Impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation by Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptides. J Neurosci Res. 2000;60:65–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000401)60:1<65::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agostinho P, Cunha RA, Oliveira C. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2766–2778. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo J, Cai W, Wu T, Xu B. Phytochemical distribution in hull and cotyledon of adzuki bean (Vigna angularis L.) and mung bean (Vigna radiate L.), and their contribution to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic activities. Food Chem. 2016;201:350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]