Abstract

Background

Many patients in Germany use naturopathic treatments and complementary medicine. Surveys have shown that many also use them as a concomitant treatment to surgery.

Methods

Multiple databases were systematically searched for systematic reviews, controlled trials, and experimental studies concerning the use of naturopathic treatments and complementary medicine in the management of typical postoperative problems (PROSPERO CRD42018095330).

Results

Of the 387 publications identified by the search, 76 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. In patients with abnormal gastrointestinal activity, acupuncture can improve motility, ease the passing of flatus, and lead to earlier defecation. Acupuncture and acupressure can reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting, as well as pain. Moreover, aromatherapy and music therapy seem to reduce pain, stress and anxiety and to improve sleep. Further studies are needed to determine whether phytotherapeutic treatments are effective for the improvement of gastrointestinal function or the reduction of stress. It also remains unclear whether surgical patients can benefit from the methods of mind body medicine.

Conclusion

Certain naturopathic treatments and complementary medical methods may be useful in postoperative care and deserve more intensive study. In the publications consulted for this review, no serious side effects were reported.

Complementary medicine (CM) and naturopathic treatments (NT) are relevant topics for clinically active physicians. Many patients either would like to have advice about CM/NT or are already using them on their own for mostly harmless and self-limiting diseases (1). Indeed, more than 50% of cancer patients report using CM/NT. This not only affects primary care physicians, but also oncologists, radiotherapists, anesthesiologists, palliative care physicians, and surgeons (1). Nonetheless, little-to-no efforts seem to have been made at integrating CM/NT into everyday surgical routines. Surgeons are confronted not only with the needs of cancer patients but also with those of non-cancer patients undergoing surgery, as up to 30% of patients in this group also report using CM/NT (2, 3). Furthermore, although up to 60% of patients who undergo surgery would like complementary medical advice, almost none of them discuss this with the treating surgeon (3). This is a critical point, as self-medication with herbal supplements can lead to interactions with other drugs and cause risks, such as interference with blood clotting. This article therefore aims to give an overview of possible supportive CM/NT approaches in surgery while at the same time addressing their risks.

Methods

After evaluation of typical postoperative problems by the authors, a systematic literature review was conducted via Medline, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and experimental human studies, as well as systematic reviews, were included. Detailed information on the methodology is presented in the eMethods section and in the eBox. This review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018095330).

eBOX. Keyword search.

-

Typical postoperative problems (as evaluated by all authors)

Disturbance of gastrointestinal function

(postoperative nausea and vomiting [PONV], paralytic ileus)

Wound infection/disturbed wound healing

Anastomotic leak

Pain

Sleep disturbances and stress-related symptoms

Delayed postoperative recovery

-

- Possible treatment options to improve the typical postoperative problems (as evaluated by the two authors who are naturopaths, AKL and RH)

“Acupuncture”

“Acupressure”

“Ginger”

“Black pepper”

“Artichoke”

“Psyllium” (as well as “fleaseed” and “plantago”)

“Honey”

“Music therapy”

“Aroma therapy”

“Essential oil”

“Valerian”

“Humulus”

“Lavender”

“Mindfulness-based stress reduction”

“Mindfulness”

“Mind body medicine”

Search strategy

Search command: “keyword from list 2” [tiab] + surgery [tiab] + study design limit: systematic review

If no result: re-search without study design limit. The complete preset search period of the search engine was used. No limitations were applied for year of publication. Language limitations were set to considering only articles in English, German, Spanish, French, Italian, or Greek.

Results

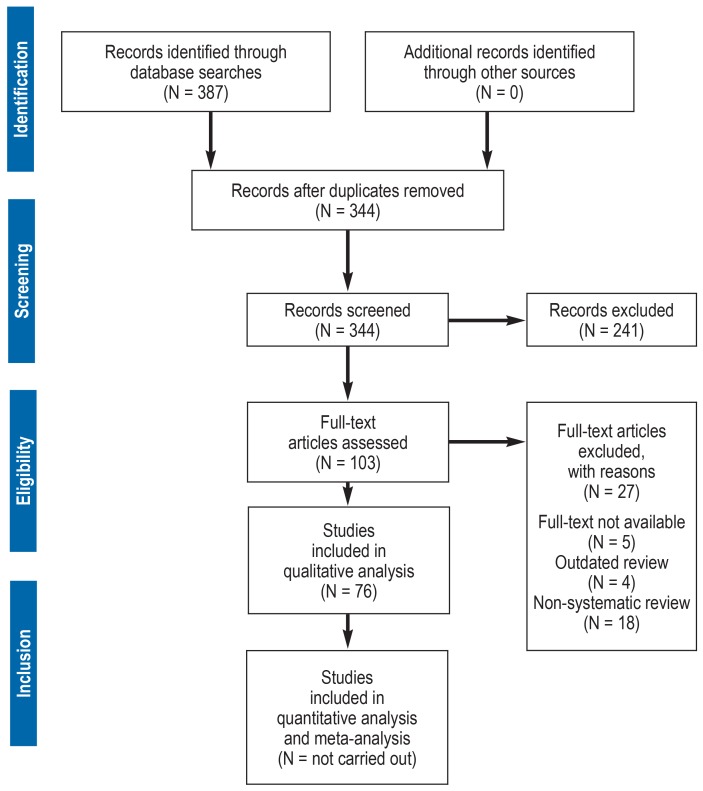

A total of 387 references were identified, of which 76 were suitable for evaluation after checking the inclusion and exclusion criteria (efigure).

eFigure.

PRISMA flow chart

Improvement of gastrointestinal function

Three systematic reviews (two of high quality) were identified that reported the use of acupuncture and acupressure for impaired gastrointestinal function following surgery (Table 1, eTable 1). All three reviews concluded that the stimulation of acupuncture points can improve motility and lead to both shorter time to first flatus and earlier defecation after surgery. A further eleven systematic reviews (three of high quality, and five of moderate quality) focused on treating postoperative nausea and vomiting through acupuncture and acupressure. Of these, nine reviews reported a positive effect (Table 1, eTable 1).

Table 1. Acupuncture and acupressure*.

| Year | Intervention | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| Symptom: Anxiety | ||||||

| 2015 (e4) |

3 × auricular acu‧puncture vs. sham | 67 | Children | Mixed | SR, Q high | Anxiety reduction (YPAS): WMD = −17 (RR: [−30.51; −3.49]) |

| 2015 (e12) |

1–3 × auricular acupuncture vs. sham | 451 | Mixed | Mixed | SR, Q moderate | Anxiety reduction: SMD = –1.11 (95% CI: [−1.61; −0.61]; p <0.01) |

| Symptom: Gastrointestinal dysfunction | ||||||

| 2016 (e40) |

Acupuncture vs. sham/ standard |

540 | Cancer patients |

Colorectal surgery |

SR, Q high | Flatus: WMD = −7.48 h (95% CI: [−14.58; −0.39]) Defecation: WMD = −18.04 h (95% CI: [−31.9; −4.19]) |

| 2017 (e49) |

Acupuncture or acupressure vs. sham/ standard |

776 | Cancer patients |

Abdominal surgery |

SR, Q high | Flatus: SMD = −0.82 (95% CI: [−1.47; −0.17]); Defecation: SMD = −0.98 (95% CI: [−1.73; −0.22]) |

| Symptom: Pain | ||||||

| 2015 (e48) |

Acupuncture and acupressure vs. sham |

4578 | Adults | Mixed | SR, Q high | Pain: SMD = −1.05 (95% CI: [−1.44; −0.67]; p <0.01 [vs. control]), smd = −0.72 (95% CI: [−1.03; −0.41]; p <0.01 [vs. sham]) |

| 2016 (e40) |

Acupuncture vs. sham/ standard |

540 | Cancer patients |

Colorectal surgery |

SR, Q high | No effect on sensation of pain or use of analgesics |

| 2016 (e73) |

Acupuncture vs. sham | 682 | Adults | Mixed | SR, Q moderate | Pain: SMD = −1.27 (95% CI: [−1.83; −0.71]; p <0.01); opioids (dose given in mg): smd = −0.72 (95% CI: [−1.2; −0.22]; p <0.01) |

| Symptom: Nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| 2012 (e26) |

Acupressure of PC 6 | 649 | Women | Cesarean | SR, Q high | Reduced intraoperative nausea: RR = 0.59 (95% CI: [0.38; 0.9]); no postoperative effect |

| 2015 (e44) |

Acupuncture vs. acupressure of PC 6 |

7667 | Mixed | Mixed | SR, Q high | Nausea: RR = 0.68 (95% CI: [0.6; 0.77]) Vomiting: RR = 0.6 (95% CI: [0.51; 0.71]) |

| 2016 (e40) |

Acupuncture vs. sham/ standard |

540 | Adult cancer patients |

Colorectal surgery |

SR, Q high | No effect |

* The complete table is available on the internet as eTable 1

CI, confidence interval; N, sample size; PC 6, pericardium 6 point; Q, quality determined by AMSTAR score; RR, relative risk; sham, acupuncture/acupressure at points for which no healing effects have been attributed; SMD, standardized mean difference; SR, systematic review; WMD, weighted mean difference; YPAS, Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale

eTable 1. Acupuncture and acupressure.

| Reference *1 | Year | Intervention*2 | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality*3 | Results |

| Symptom: Anxiety | |||||||

| (e4) | 2015 | 3 × preoperative auricular acupuncture by parents at relaxation points vs. sham | 67 | Children | Mixed | Systematic review; quality: high | Reduced anxiety (mYPAS): WMD = −17 (95% CI: [−30.51; −3.49]); increased cooperativeness: RR = 1.59 (95% CI: [1.01; 2.53]) |

| (e12) | 2015 | 1–3 × preoperative acupuncture at relaxation points, either as a one-time stimulation for 20–30 min or as a continuous stimulation on ear, vs. sham | 451 | Mixed | Before every medical treatment or operation | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced anxiety (VAS): SMD = −1.11 (95% CI: [−1.61; −0.61], p <0.01) |

| Symptom: Gastrointestinal dysfunction | |||||||

| (e74) | 2015 | Finger or body acupuncture or acupressure | *5 | Women | Gynecologic (ERAS program) | Systematic review; quality: low | Improved motility: 50%, subjective (assessed by auscultation) |

| (e40) | 2016 | Postoperative acupuncture (needle/electro) over up to 10 days, daily, for 20–30 min vs. sham or no intervention | 540 | Adult cancer patients | Colorectal surgery | Systematic review; quality: high | Shorter time to first flatus: MD = −7.48 h (95% CI: [−14.58; −0.39]); shorter time to first defecation: MD = −18.04 h (95% CI: [−31.9; −4.19]) |

| (e49) | 2017 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) or acupressure for 10–45 min vs. sham, or no intervention, different frequencies | 776 | Adult cancer patients | Oncological abdominal surgery | Systematic review; quality: high | Shorter time to first flatus: SMD = −0.82 (95% CI: [−1.47; −0.17]); shorter time to first defecation: SMD = −0.98 (95% CI: [−1.73; −0.22]); only acupressure: shorter time to first flatus: SMD = −0.69 (95% CI: [−1.06; −0.31]), no influence on defecation or length of hospital stay |

| Symptom: Postoperative recovery | |||||||

| (e11) | 2015 | Perioperative electroacupuncture | 321 | Mixed | Cardiac surgery | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Less sedatives: SMD = 0.73 (95% CI: [0.11; 1.35], p = 0.02); shorter ventilation time: SMD = 0.38 (95% CI: [0.13; 0.63], p <0.01); reduced inotropes and vasoactive substances: SMD = 0.952 (95% CI: [0.43; 1.48], p <0.01) |

| (e5) | 2017 | Perioperative electroacupuncture | 700 | Adults | Craniotomy | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced need for anesthesia: SMD = 0.475 (95% CI: [0.36; 0.59], p <0.01); earlier extubation: SMD = 0.38 (95% CI: [0.16; 0.60], p <0.001); earlier transfer: SMD = 0.30 (95% CI: [0.10; 0.50], p <0.01); reduced value of S100β: SMD = 0.52 (95% CI: [0.21; 0.83], p <0.01) |

| Symptom: Pain | |||||||

| (e46) | 2005 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) before anesthesia, different durations |

1689 | Adults | Mixed | Systematic review; quality: moderate | No conclusive results due to inhomogeneous data |

| (e62) | 2012 | Acupuncture vs. sham | 70 | Adults | Knee arthroplasty (TKA), shoulder operation | Systematic review; quality: moderate | No conclusive results due to inhomogeneous data |

| (e15) | 2013 | Perioperative acupressure, auricular or body acupuncture vs. sham | 222 | Adults | Ambulatory knee surgery | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced pain (in one of four studies); reduced need for analgesics (in three of four studies: p = 0.01 as well as p = 0.04; in one, not significant) |

| (e22) | 2015 | Perioperative acupuncture vs. sham or no intervention | 480 | Adults | Back surgery | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced pain (VAS after 24 h): acupuncture vs. sham: SMD = −0.67 (95% CI: [−1.04; −0.31], p <0.01, n = 123); acupuncture vs. no treatment: SMD = −0.69 (95% CI: [−1.06; −0.33], p <0.01, n = 124); reduced need for opioids: SMD = −0.77 (95% CI: [−1.14; −0.41], p <0.01) |

| (e51) | 2014 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) or acupressure vs. sham | *4 | Adults | Plastic surgery | Systematic review; quality: low | Reduced need for opioids: WMD (after 8 h) = −3.14 mg (95% CI: [−5.15; −1.14]),WMD (after 24 h) = −8.33 mg (95% CI: [−11.06; −5.61]),WMD (after 72 h) = −9.14 mg (95% CI: [−16.07; −2.22]) |

| (e74) | 2015 | Auricular acupuncture vs. electrodes at the same site | *5 | Women | Gynecologic (ERAS-program) | Systematic ‧review; quality: low; only one study on pain | No difference |

| (e48) | 2015 | Acupuncture (needle/electro/plaster or seed) and acupressure vs. sham, no intervention or herbal therapy, different durations/frequencies | 4578 | Adults | Mixed | Systematic review; quality: high | Reduced pain (according to VAS): acupuncture vs. control: SMD = −1.05 (95% CI: [−1.44; −0.67], p <0.01, n = 1227), acupuncture vs. sham: smd = −0.72 (95% ci: [−1.03; −0.41], p <0.01, n = 1284); reduced need for opioids: smd = −4.99, (95% ci: [−7.51; −2.47], p <0.01, n = 399) |

| (e73) | 2016 | Perioperative acupuncture, different duration/ frequency, vs. sham | 682 | Adults | Mixed | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced pain on 1st postoperative day: SMD = −1.27 (95% CI: [−1.83; −0.71], p <0.01); reduced need for opioids: smd = −0.72 (95% ci: [−1.21; −0.22], p <0.01) (dose measured in mg) |

| (e40) | 2016 | Postoperative acupuncture (needle/electro; up to 8 points) over up to 10 days, 20–30 min vs. sham or no intervention | 540 | Adult cancer patients | Colorectal surgery | Systematic review; quality: high | No effect on pain sensation or need for analgesics |

| (e70) | 2017 | Preoperative electroacupuncture vs. sham | 176 | Adults | Craniotomy | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Better control of pain, reduced need for opioids, reduced dizziness (no calculations available) |

| Symptom: Nausea and vomiting | |||||||

| (e71) | 1996 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) and acupressure (also with armband) vs. sham, antiemetic or no inter‧vention | 2305 | Mixed | Mixed (>50% gynecologic) | Systematic review; quality: low | Inhomogeneous study situations, overall possible positive effects |

| (e45) | 1999 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) or acupressure vs. sham, no intervention or antiemetic | 1679 | Mixed | Mixed (>50% gynecologic) | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Better than placebo; early nausea (<6 h postoperative): rr = 0.34 (95% ci: [0.2; 0.58], nnt = 4), late nausea (>6 h postoperative): RR = 0.47 (95% CI: [0.34; 0.64], NNT = 5); comparable to antiemetics for early vomiting (RR = 0.89 (95% CI: [0.47; 1.67], NNT = 63) and late vomiting (RR = 0.8 (95% CI: [0.35; 1.81], NNT = 25), no difference for children |

| (e26) | 2012 | Acupressure of Pericardium 6 | 649 | Women | Cesarean | Systematic review; quality: high | Reduced intraoperative nausea: RR = 0.59 (95% CI: [0.38; 0.9]), no effect on postoperative nausea or on intra- or postoperative vomiting |

| (e21) | 2013 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) and acupressure (also with armband) of Pericardium 6 vs. sham or no intervention | 2534 | Mixed | Mixed (47% gynecologic) | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Acupuncture: reduced frequency of vomiting (0–6 h): RR = 0.36 (95% CI: [0.19; 0.71], p <0.01), reduced nausea (0–24 h): rr = 0.25 (95% ci: [0.1; 0.61], p <0.01); acupressure: reduced nausea : rr = 0.71 (95% ci: [0.57; 0.87], p = 0.01), reduced frequency of vomiting (>24 h): RR = 0.62 (95% CI: [0.49; 0.8], p <0.01) |

| (e20) | 2014 | Acupuncture vs. antiemetic or no intervention, different durations/frequencies | 370 | Adults | Abdominal surgery | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Improvement of gastroparesis: only acupuncture: RR = 1.27 (95% CI: [1.13; 1.44], p <0.01) acupuncture and medication: RR = 1.37 (95% CI: [1.18; 1.58], p <0.01) |

| (e51) | 2014 | Acupuncture (needle/electro) or acupressure vs. sham | *4 | Adults | Plastic surgery | Systematic review; quality: low | Reduced nausea : RR = 0.67 (95% CI: [0.53; 0.86]) |

| (e44) | 2015 | Perioperative acupuncture (also electro-) or acupressure (using an armband) of Pericardium 6 | 7667 | Mixed | Mixed | Systematic review; quality: high | Reduced nausea : RR = 0.68 (95% CI: [0.6; 0.77], N = 4742); reduced frequency of vomiting: RR = 0.6 (95% CI: [0.51; 0.71], N = 5147); reduced need for emergency antiemetics: RR = 0.64 (95% CI: [0.55; 0.73], N = 4622) Similar effects as conventional antiemetics in direct comparison |

| (e74) | 2015 | Acupressure | *5 | Women | Gynecologic (ERAS-program) | Systematic review; Quality: low | Reduced frequency of vomiting, reduced nausea : mean 27% (results of other studies: 30%, 16%, 38%, 32%) |

| (e40) | 2016 | Postoperative acupuncture (needle/electro; up to 8 points) over up to 10 days, daily, 20–30 min vs. sham, or no intervention | 540 | Adult cancer patients | Colorectal surgery | Systematic review; quality: high | No effect on nausea or vomiting |

| (e5) | 2017 | Perioperative electroacupuncture | 700 | Adults | Craniotomy | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced frequency of vomiting, reduced nausea : OR = 2.56 (95% CI: [1.18; 5.55], p <0.02) |

| (e50) | 2017 | Perioperative acupressure | 894 | Adults | Gynecologic and abdominal surgery | Systematic review; quality: moderate | Reduced nausea : OR = 0.52 (95% CI: [0.39; 0.7], p <0.01]; reduced frequency of vomiting: OR = 0.54 (95% CI: [0.39; 0.75], p <0.01) |

*1 See eReferences, *2 Unless otherwise stated, the reference group was inhomogeneous (sham acupuncture/no intervention/other intervention),

*3 Calculated according to AMSTAR score, *4 15 RCTs evaluated, total number of patients not given; *5 Total number not given

CI, confidence interval; ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; mYPAS, modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale (20– 60); N, sample size; NNT, number needed to treat; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk;

sham, acupuncture/acupressure at points for which no healing effects are attributed; SMD, standardized mean difference; VAS, Visual Analog Scale (1– 10); WMD, weighted mean difference

Table 2 and eTable 2 indicate the effectiveness of aromatherapy with various substances at the onset of, and during courses of, nausea and vomiting. A total of nine studies were evaluated, including seven RCTs (of which only one was of good quality) and one systematic review (of high quality). Four RCTs showed that aromatherapy can significantly improve nausea and vomiting. The systematic review, however, showed only low evidence for the use of aromatherapy for reducing nausea and vomiting, with poor overall study quality (e1).

Table 2. Effect of perioperative or postoperative aromatherapy on anxiety, stress, pain, nausea, vomiting, and sleep quality*.

| Year | Intervention | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| Symptom: Anxiety and stress | ||||||

| 2013 (e58) |

Bergamot oil vs. placebo (diffuser) |

109 | Adults | Ambulatory ‧‧surgery | RCT, Q good | Anxiety reduction: −3 vs. −2 pts (p = 0.02) |

| 2014 (e65) |

Postoperative inhalation of lavender vs. water |

60 | Adults | Cardiac surgery | RCT, Q good | Anxiety reduction: −6.13 vs. −5.27 pts (immediate), −7.4 vs. 6.44 pts (3 rd postoperative day) |

| Symptom: Pain | ||||||

| 2014 (e7) |

Massage with eucalyptus–lemon oil vs. carrier oil vs. standard |

60 | Adults | Vitrectomy | RCT, Q good | Pain reduction: shoulder, −1.1 vs. −0.8 vs. 0.15 FPS; neck, −0.85 vs. −0.8 vs. 0.15 FPS; back, −0.75 vs. −0.6 vs. 0.3 FPS; waist, −0.9 vs. −1 vs. 0.1 FPS; arms, −0.85 vs. −0.05 vs. −0.05 FPS |

| Symptom: Nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| 2018 (e1) |

Perioperative inhalation of diverse aromatic oils vs. placebo | 402 | Mixed | Mixed | SR, Q high | Nausea: SMD = −0.22 (95% CI: [−0.63; 0.18]; p = 0.28), antiemetic reduction: RR = 0.60 (95% CI: [0.37; 0.97], p = 0.04) |

| 2016 (e37) |

Inhalation of ginger/lavender/menthol vs. NaCl | 80 | Children (4–16 years) |

Ambulatory surgery |

RCT, Q good | Reduction of retching: 90% vs. 78%; reduction of antiemetics: 52% vs. 44%; reduction of vomiting: 9% vs. 11% |

* The complete table is available on the internet as eTable 2 CI, confidence interval; FPS, Faces Pain Scale; N, sample size; NaCl, sodium chloride saline solution; pts, points; Q, quality determined by AMSTAR score (for SR) or Jadad score (for RCT); RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, relative risk; SMD, standardized mean difference; SR, systematic review

eTable 2. Effect of perioperative or postoperative aromatherapy on anxiety, stress, pain, nausea, vomiting, and sleep quality.

| Reference *1 | Year | Intervention | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| Symptom: Anxiety and stress | |||||||

| (e24) | 2011 | Preoperative inhalation of lavender oil or water | 72 | Adults | Cardiac and general surgery | Quasi-experimental study, quality*2: bad |

STAI (intervention vs. placebo): −12.4 vs. −2.4 pts (p <0.01) |

| (e33) | 2012 | Postoperative massage with mandarin oil (A), carrier oil (B), or no intervention (C) |

60 | Children up to 3 years |

Craniofacial surgery |

RCT, quality*2: bad |

COMFORT-B (groups A / B / C):11.1 / 11.6 / 12.1 pts; NAS (stress): 2 / 4 / 3 pts; NAS (pain): 1 / 0 / 1 pt (p not given) |

| (e58) | 2013 | Aroma diffuser with bergamot oil or placebo | 109 | Adults | Ambulatory surgery |

RCT, quality*2: good |

STAI (intervention vs. placebo): −3 vs. −2 pts (p = 0.02) |

| (e65) | 2014 | Inhalation on the 2nd and 3rd postoperative days of lavender oil versus water | 60 | Adults | Cardiac surgery | RCT, quality*2: good |

STAI (intervention vs. placebo): before intervention : 48.73 vs. 48 pts; after intervention 42.6 vs. 42.73 pts, on 3rd postoperative day: 41.33 vs. 41.56 pts (p not significant at any point) |

| (e72) | 2017 | Preoperative inhalation of lavender essential oil versus no intervention |

100 | Adults | Ambulatory ENT surgery |

Controlled study, quality*2: bad |

Anxiety reduction according to VAS (intervention vs. control): −1.07 vs. −0.01 (p <0.01) |

| (e69) | 2017 | Aromatherapy during biopsy with lavender-sandalwood (A), orange-peppermint (B), or placebo (C) |

87 | Women | Breast biopsy | RCT, quality*2: bad | STAI: group A, from 48 to 37 pts; group B, from 43 to 37 pts; group C, from 43 to 39 pts; difference A vs. C, p = 0.03 |

| (e13) | 2018 | Preoperative massage with lavender oil or no intervention |

80 | Adults | Colorectal surgery | RCT, quality*2: bad | STAI (intervention vs. control): 35.25 vs. 45.40 pts on morning of surgery (p <0.01) |

| Symptom: Pain | |||||||

| (e39) | 2016 | Postoperative inhalation of lavender oil or oxygen |

50 | Women | Breast biopsy | RCT, quality*2: bad | NAS (Intervention vs. control): 5 min after arrival on ward 0.2 vs. 1.26 pts, after 30 min 0.6 vs. 1.1 pts, after 60 min 0.6 vs. 1.42 pts; emergency medication required: 1 vs. 6; excellent satisfaction with pain control: 92% vs. 52% (p <0.05) |

| (e38) | 2006 | Postoperative inhalation of lavender oil or baby oil | 54 | Adults | Bariatric surgery | RCT, quality*2: bad | Need for anesthesia (intervention vs. control): 42% vs. 82% (p <0.01); use of anesthesia (intervention vs. control): 2.38 mg vs. 4.26 mg morphine (p = 0.04) |

| (e27) | 2011 | Perioperative inhalation of lavender oil or neutral oil | 200 | Women | Cesarean | RCT, quality*2: bad | VAS (intervention vs. control): baseline 6.16 vs. 5.78, after 30 min 3.67 vs. 5.29 (p <0.01), after 8 h 2.01 vs. 4.64 (p <0.01), after 16 h 0.67 vs. 4.05 (p <0.01) |

| (e67) | 2013 | Postoperative inhalation of lavender oil or no intervention | 48 | Children (6–12 years) |

Tonsillectomy | RCT, quality*2: bad | Number of oral paracetamol doses (intervention vs. control): 1st day, 2.1 vs. 2.6 (p <0.05), 2nd day: 2.1 vs. 3.4 (p <0.01), 3rd day: 1.3 vs. 2.4 (p <0.01) vas: 1st day, 7.0 vs. 7.6 pts, 2nd day: 6.8 vs. 7.0 pts, 3rd day 3.9 vs. 5.9 pts (p not given) |

| (e63) | 2014 | Postoperative inhalation of lavender oil | 40 | Adults | Cardiac surgery | Single-arm study, quality*2: bad; no control group | NAS reduction: from 5.6 to 5.0 pts after lavender inhalation (p not significant) |

| (e7) | 2014 | Massage of different body regions with eucalyptus-lemon oil (A), neutral oil (B), or no intervention (C) |

60 | Adults | Vitrectomy | RCT, quality*2: good |

FPS, day 1 (for groups A / B / C): shoulder: −1.1 / −0.8 / +0.15 pts; neck: −0.85 / −0.8 / +0.15 pts; back: −0.75 / −0.6 / +0.3 pts; waist: −0.9 / −1 / +0.1 pts; arms: −0.85 / −0.05 / −0.05 pts (p not given); pain reduction also observed on days 2 and 3 (data not shown) |

| (e11) | 2015 | Inhalation on 2nd postoperative day of lavender oil or oxygen | 50 | Adults | Cardiac surgery | RCT, quality*2: bad |

VAS (intervention / placebo): baseline, 5.62 / 6.27 pts; after 5 min, 4.26 / 6.23 pts (p <0.01); after 30 min, 4.39 / 6.3 pts (p <0.01); after 60 min, 4.11 / 6.35 pts (p <0.01) |

| (e53) | 2015 | Postoperative inhalation of rose oil or almond oil | 64 | Children (3–6 years) |

Mixed | RCT, quality*2: bad |

TPPPS (intervention / placebo) directly at arrival on ward: 3.8 vs. 3.1 pts, after 3 h: 1.0 / 2.6 pts, after 6 h: 1.03 vs. 2.03 pts, after 9 h: 0.9 / 1.6 pts, after 12 h 0.4 / 1.1 pts (p <0.01 for all time points) |

| Symptom: Nausea and vomiting | |||||||

| (e9) | 2004 | Inhalation (upon request) of peppermint, propanol, or NaCl | 33 | Adults | Ambulatory surgery |

RCT, quality*2: bad |

VAS (for all therapies): −1.79 pts (p <0.05), but not difference between the groups |

| (e31) | 2011 | Inhalation (upon request; using an aroma pad) of mix of ginger, spearmint, peppermint and cardamom (A) vs. ginger alone vs. isopropyl alcohol vs. NaCl | 303 | Adults | Gynecologic abdominal surgery |

RCT, quality*2: bad |

Ginger (OR = 1.86 [95% CI: (1.22; 3.0), p <0.01]) or mix (or = 2.7 [95%-ci: (1.78; 4.56), p <0.01]) better than nacl or alcohol (95% ci: [1.08; 2.13], p = 0.02; 95% ci: [1.5; 3.17], p <0.01) for nausea and need for antiemetics (95% ci: [−43.1; −8], p = 0.02; 95% ci: [−57.8; −22.7], p <0.01) |

| (e25) | 2012 | Inhalation (upon request) of peppermint oil or NaCl, or treatment with Zofran | 71 | Women | Mixed | RCT, quality*2: bad |

VAS (1–20, peppermint / NaCl / Zofran): before intervention: 12.5 / 11.9 / 11.3 pts; after 5 min: 8.0 / 7.5 / 6.8 pts; after 10 min: 2.4 / 3.4 / 5.8 pts (p not significant at any time point) |

| (e42) | 2012 | Inhalation of peppermint oil or placebo, or treatment with standard antiemetics | 35*3 | Women | Cesarean | RCT, quality*2: bad |

Reduction of nausea and vomiting for 17 out of 19 patients at 2 min and 5 min after peppermint treatment; no improvement after placebo or anti‧emetics (at either 2 min or 5 min) |

| (e1) | 2018 | Perioperative inhalation of different aromatic oils (including peppermint) or placebo | 402 | Mixed | Mixed | Systematic review, quality*2: high |

General aromatherapy vs. placebo: SMD = −0.22 (95% CI: [−0.63; 0.18], p = 0.28; reduced need of antiemetic treatment after aromatherapy: RR = 0.60 (95% CI: [0.37; 0.97], p =0.04; peppermint inhalation vs. placebo: SMD = −0.18 (95% CI: [−0.86; 0.49], p = 0.59 |

| (e30) | 2014 | Inhalation for nausea (upon request) of spearmint, peppermint, lavender, and ginger vs. placebo | 339 | Adults | Mixed | RCT, quality*2: bad |

Nausea for 121 Patienten, of whom 94 were randomized (54 intervention, 40 placebo); NAS (intervention / placebo): initial 5.4 / 5.6 pts, after use 3.4 / 4.4 pts (p = 0.03) |

| (e8) | 2015 | Postoperative inhalation (2 drops every 30 min, aroma pad) of ginger extract or NaCl | 120 | Adults | Nephrectomy | RCT, quality*4: bad |

VAS (intervention / placebo): 7.1 / 7.4 pts after 30 min, 4.2 / 7.4 pts after 60 min, 2.4 / 7.4 pts after 90 min, 2.0 / 7.4 after 120 min, 1.1 / 6.5 after 6 h (for all, p <0.01); need for ondansetron: 1.9 / 3.9 mg (p <0.01) |

| (e54) | 2015 | Inhalation (upon request) of spearmint, peppermint, lavender, and ginger | 70 | Adults | Ambulatory surgery |

Exploratory study, quality*4: bad; no control group |

Nausea reported for 25 patients; NAS (after use), −4.78 pts (p not given) |

| (e47) | 2017 | Postoperative inhalation of ginger oil or NaCl | 60 | Adults | Abdominal surgery |

Quasi-experimental study, quality*4: bad | RINVR (intervention / placebo): 11.8 / 11.57 pts (baseline), 1.6 / 10.47 pts after 6 h, 1.0 / 9.07 pts after 12 h, 0.83 / 7.2 pts after 24 h; lower pts after intervention (p <0.01) |

| (e37) | 2016 | Inhalation for nausea of lavender, menthol, ginger, or NaCl | 80 | Children (4–16 years) |

Ambulatory surgery | RCT, quality*2: good |

BARF (intervention / placebo): reduction by 2 pts, 90% / 78%; use of antiemetic therapy, 52% / 44%; vomiting, 9% / 11% (p not significant in any case) |

| Improvement of sleep quality | |||||||

| (e36) | 2017 | Postoperative massage with lavender oil or no intervention | 60 | Adults | General surgery | Experimental study, quality*4: bad |

RCSF: increase of 25.72 pts (p <0.01) (as compared to control) |

| (e13) | 2018 | Preoperative massage with lavender oil or no intervention | 80 | Adults | Colorectal surgery | Experimental study, quality*4: bad |

RCSF: increase of 24.02 pts (p <0.01) (as compared to control) |

*1 See eReferences; *2 Calculated according to the Jadad score scale; *3 Unbalanced group sizes: of the 35 patients, 22 were in the intervention group, 8 in the placebo group, and 5 in the standard therapy group; *4 Calculated according to the AMSTAR score scale BARF, Baxter Animated Retching Faces scale; CI, confidence interval; COMFORT-B, comfort behavior scale (pain, sedation) for young children; FPS, Faces Pain Scale; N, sample size; NaCl, sodium chloride saline solution; NAS, numeric analog scale (1– 10);

OR, odds ratio; pts, points; RCSF, Richard Campbell sleep questionnaire; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RINVR, Rhodes Index of Nausea, Vomiting, and Retching; RR, relative risk; SMD, standardized mean difference;

STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; TPPPS, Toddler-Preschooler Postoperative Pain Scale; VAS, Visual Analog Scale (1– 10)

Possible uses of phytotherapy for antiemesis are listed in Table 3 and eTable 3. Currently, studies on treatments of surgical patients have only tested the effects of ginger. We did not find any results for other substances that could have a positive effect on gastrointestinal function, such as artichokes or black pepper. The mechanism of action of ginger has now been elucidated. Similar to the mechanisms of the setron group antiemetics, it seems to be based on the influence of the ingredients gingerol and shogaol on the 5-HT3 receptors (4). Although the twelve RCTs examined here were mostly of high methodological quality (with only two of poor methodological quality), the results from them were inhomogeneous (Table 3, eTable 3). In fact, some studies even showed an increase of nausea and vomiting during therapy with ginger. Possible side effects of taking ginger are heartburn and upper abdominal discomfort. Traditionally, ginger is used once nausea has started. As none of the studies examined the effects of a symptom-bound therapy, it still remains unclear whether ginger in this case could have a positive effect.

Table 3. Potential uses of phytotherapy for surgical patients*.

| Year | Intervention | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| Symptoms: Anxiety and cognitive dysfunction, studies on therapy with valerian | ||||||

| 2015 (e28) |

1060 mg valerian vs. placebo |

61 | Adults | Cardiac surgery | RCT, Q good | Mini-Mental State: 26.5 vs 24 pts on 10th day; 27.5 vs 24.8 pts on 60th day (OR = 0.11 [95% CI: (0.02; 0.55)]) |

| 2014 (e61) |

Preoperative 100 mg valerian vs placebo |

20 | Adults (17–31 years) |

OMSF (wisdom teeth) |

RCT, Q good | Anxiety: 20% vs 55% (as rated by scientists; p = 0.02), 25% vs 50% (as rated by surgeons, p = 0.102) |

| Symptoms: Nausea and vomiting, studies on therapy with ginger | ||||||

| 1993 (e60) |

Preoperative, 10 mg MCP vs 1 g ginger vs placebo |

120 | Women | Gynecologic (lap.) |

RCT, Q good | Nausea: 27% vs 21% vs 41% (p = 0.05); patients who used antiemetics: 13 vs 6 vs 15 (p = 0.02) |

| 1995 (e10) |

Preoperative, placebo vs 0.5 g ginger vs 1 g ginger |

108 | Women | Gynecologic (lap.) |

RCT, Q good | Nausea: 22% vs 33% vs 36%; vomiting:14% vs 17% vs 31% (OR [per 0.5 g ginger] = 1.39 for nausea and OR [per 0.5 g ginger] = 1.55 for vomiting) |

| 2006 (e57) |

Preoperative, 1 g ginger vs P |

120 | Women | Gynecologic | RCT, Q good | Nausea: 48% vs 67%; vomiting: 28% vs 47% (p = 0.04); nausea score: 0 vs 0 pts (immediately), 1 vs 2 pts (at 2/6/12 h), 0.5 vs 0.5 pts (24 h) |

| 2003 (e23) |

Perioperative, placebo vs 300 mg ginger vs 600 mg ginger |

180 | Women | Gynecologic (lap.) | RCT, Q good | Nausea: 49% vs 56% vs 53 % Vomiting: 27% vs 43% vs 40% |

| 2006 (e68) |

Preoperative, placebo vs 0.5 g ginger |

120 | Adults | Thyroidectomy | RCT, Q good | Nausea: 23% vs 20%; Vomiting: 5% vs 7% Repeated vomiting: 3% vs 0% |

| 2013 (e35) |

Preoperative, 1 g ginger vs placebo |

239 | Women | Cesarean | RCT, Q good | Intraoperative nausea: 52% vs 61%; Vomiting: 27% vs 37%; Episodes of nausea: VAS = −0.4 (95% CI: [0.74; 0.05]; p = 0.02) |

| 2013 (e56) |

Preoperative, 1 g ginger vs placebo |

160 | Adults | Mixed | RCT, Q good | Nausea (VAS): 2.9 vs 3.5 pts (2 h; p = 0.04) |

| 2017 (e64) |

Preoperative, 1 g ginger vs 2 × 500 mg ginger vs placebo |

122 | Adults | Cataract surgery |

RCT, Q good | Nausea: 10% vs 16% vs 0% (immediately; p <0.01); 15% vs 13% vs 0% (at ward; p >0.3); 10% vs 8% vs 0% (2 h; p = 0.04); 3% vs 13% vs 2% (6 h; p <0.02) |

| 2018 (e14) |

Preoperative, 500 mg ginger vs placebo |

150 | Women | Chole cystectomy (lap.) |

RCT, Q good | Nausea: 2.0 vs 2.9 pts (2 h, p = 0.03); 2.8 vs 3.2 pts (4 h; p = 0.35); 1.8 vs 2.0 pts (6 h; p = 0.62); 0.4 vs 1.8 (12 h, p = 0.04) |

* The complete table is available on the internet as eTable 3

CI, confidence interval; lap., laparoscopic; MCP, metoclopramide drops; N, sample size; OR, odds ratio; pts, points;

OMFS, oral and maxillofacial surgery; Q, quality determined by Jadad score; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VAS, Visual Analog Scale

eTable 3. Potential uses of phytotherapy for surgical patients*1.

| References*1 | Year | Intervention | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality*2 | Results |

|

Symptom: Anxiety and cognitive dysfunction Studies on therapy with valerian | |||||||

| (e28) | 2015 | Group 1: 1060 mg valerian Group 2: placebo (given perioperatively, every 12 h for 8 weeks) |

61 | Adults | Cardiac surgery | RCT, quality: good |

MMSE (group 1 vs 2): preoperatively, 27.0 vs 27.0 pts; on 10th postoperative day, 26.5 vs 24.0 pts, on 60th postoperative day, 27.5 vs 24.8 pts (OR = 0.11; 95% CI: [0.02; 0.55]) |

| (e61) | 2014 | Group 1: 100 mg valerian Group 2: placebo (given preoperatively) |

20 | Adults (17–31 years) |

OMSF (wisdom teeth) | RCT, quality: good |

DAS (group 1 vs 2): anxiety (as rated by scientists), 20% vs 55% (p = 0.02); anxiety (as rated by surgeons), 25% vs 50% (not significant) |

|

Symptom: Nausea and vomiting Studies on therapy with ginger | |||||||

| (e17) | 1990 | Group 1: 1 g ginger and placebo injection Group 2: placebo and MCP injection Group 3: placebo and placebo injection (given preoperatively) |

60 | Women | Gynecologic | RCT, quality: bad |

Nausea rate: 28% in group 1, 30% in group 2, and 51% in group 3 (p = 0.05); patients who required additional antiemetics: none in group 1, one in group 2, and six in group 3 (p = 0.05) |

| (e60) | 1993 | Group 1: 10 mg MCP Group 2: 1 g ginger Group 3: placebo (lactose) (given preoperatively) |

120 | Women | Gynecologic (laparoscopic) | RCT, quality: good |

Nausea rate: 27% in group 1, 21% in group 2, and 41% in group 3 (p = 0.05); patients who required additional antiemetics: 13 in group 1, six in group 2, and 15 in group 3 (p = 0.02) |

| (e10) | 1995 | Group 1: placebo Group2: 0.5 g ginger Group 3: 1 g ginger (given preoperatively) |

108 | Women | Gynecologic (laparoscopic) | RCT, quality: good |

Nausea vs vomiting: group 1, 22% and 14% ; group 2, 33% and 17%; group 3, 36% and 31% (OR [per 0.5 g ginger] = 01.39 for nausea; OR [per 0.5 g ginger] = 1.55 for vomiting) |

| (e57) | 2006 | Group 1: 1 g ginger Group 2: placebo (given preoperatively) |

120 | Women | Gynecologic | RCT, quality: good |

Nausea vs vomiting: group 1, 48% and 28%, group 2, 67% and 47% (p = 0.04); VAS (group 1 vs 2): immediately, 0 vs 0 ; 2 h postoperatively, 1.1 vs 2.0 ; 6 h postoperatively, 1.4 vs 2.4; 12 h postoperatively, 1.3 vs 2.0; 24 h postoperatively, 0.5 vs 0.5 |

| (e23) | 2003 | Group 1: placebo Group 2: 300 mg ginger Group 3: 600 mg ginger (given pre- and postoperatively [3 h, 6 h]) |

180 | Women | Gynecologic (laparoscopic) | RCT, quality: good |

Nausea and vomiting:group 1, 49% and27% group 2, 56% and 43% group 3, 53% and 40% , respectively |

| (e68) | 2006 | Group 1: placebo Group 2: 0.5 g ginger (given preoperatively; both groups also received dexamethasone) |

120 | Adults | Thyroidectomy | RCT, quality: good |

Nauseaa and vomiting:group 1: 23% and 5%, respectively; 3% repeated vomiting group 2: 20% and 7%, respectively; no repeated vomiting |

| (e35) | 2013 | Group 1: 1 g ginger Group 2: placebo (given preoperatively) |

239 | Women | Cesarean | RCT, quality: good |

Intraoperatively: group 1, 52% nausea (nausea episodes reduced by −0.4, [95% CI: (0.74; 0.05), p = 0.02]), 27% vomiting; group 2: 61% nausea, 37% vomiting; postoperatively, no difference |

| (e56) | 2013 | Group 1: 1 g ginger Group 2: placebo (given preoperatively) |

160 | Adults | Mixed | RCT, quality: good |

VAS (group 1 vs 2): 2.9 vs 3.5 after 2 h (p = 0.04) (only significant difference) |

| (e52) | 2014 | Group 1: 1 g ginger Group 2: placebo (given preoperatively; both also received 4 mg ondansetron) |

100 | Adults | Ambulatory surgery | RCT, quality: bad |

Group 1: no nausea or vomiting in the first 12 h Group 2: at the maximum, 22% with nausea and vomiting (depending on time measured) |

| (e75) | 2016 | Group 1: 25 droups ginger extract in water Group 2: only water (given preoperatively) |

92 | Pregnant women | Cesarean | RCT, quality: bad |

Average VAS score (group 1 vs 2): intraoperatively, 0.8 vs 2.3, p = 0.01; 2 h postoperatively, 0.3 vs 0.8, p = 0.13; 4 h postoperatively, 0.05 vs 0.1, p = 0.57 |

| (e64) | 2017 | Group 1: 1 g ginger Group 2: 2 × 500 mg ginger Group 3: placebo (given preoperatively) |

122 | Adults | Cataract surgery | RCT, quality: good |

Nausea, group 1 vs 2 vs 3: immediately postoperatively, 10% vs 16% vs 0% (p <0.01); upon arrival at ward: 15% vs 13% vs 0% (p >0.0.3); 2 h postoperatively, 10% vs 8% vs 0% (p = 0.04); 6 h postoperatively, 3% vs 13% vs 2% (p <0.02) |

| (e14) | 2018 | Group 1: 500 mg ginger Group 2: placebo (given preoperatively) |

150 | Women | Cholecystectomy (laparoscopic) |

RCT, quality: good |

Nausea, average NAS score (group 1 vs 2): 2 h postoperatively, 2.0 vs 2.9, p = 0.03; 4 h postoperatively, 2.8 vs 3.2, p = 0.35; 6 h postoperatively, 1.8 vs 2.0, p = 0.62; 12 h postoperatively, 0.4 vs 1.8, p = 0.04 |

*1 See eReferences; *2 Calculated according to Jadad score

DAS, Dental Anxiety Score; MCP, metoclopramide; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; N, sample size; NAS, Numeric Analog Scale (1– 10);

OMFS, oral and maxillofacial surgery; OR, odds ratio; pts, points; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VAS, Visual Analog Scale (1– 10)

In an Italian placebo-controlled RCT (n = 60) of good methodological quality according to Jadad-Score (eMethods), administration of 3.5 g of psyllium husk after rectal resection (STARR) resulted in significantly less obstruction one week after surgery (obstructed defecation syndrome score according to Longo [ODS]: 6.25 ± 3.55 versus 11.94 ± 4.99, p<0.01; Cleveland clinic constipation score [CCS]: 6.59 ± 2.65 versus 15.10 ± 3.33, p<0.01) and less incontinence (Wexner incontinence score, difference in scores from baseline: 0.5 versus 2.70, p<0.01) (e2). This benefit was also evident in the follow-up after six months (constipation: ODS, 3.40 ± 5.26 versus 4.97 ± 4.21, p<0.05; CCS, 5.00 ± 3.82 versus 6.63 ± 3.68, p<0.01; incontinence, –0.17 versus 1.33, p<0.01). Another controlled study of 38 patients after ileostomy (which was however of poor quality, according to its Jadad score) showed that the group of patients who ate 7 g of psyllium husk each day (n = 20) had a significantly lower ileostomy output after 90 days (–322 mL) than those in the control group (n = 18) (–95 mL; p<0.0001) (e3).

Postoperative wound infection and anastomotic insufficiency

Already in ancient Egypt, infected wounds were treated with fat and honey (5). However, only very few, small studies have addressed acute treatment of surgical wounds, as shown in an overview of the current study situation in Table 4 and eTable 4. The current data situation is heterogeneous and not convincing overall. Many other plant extracts are used worldwide in traditional medical practices for wound healing (6). However, as efficacy has so far only been investigated in isolated cases and in preclinical wound healing models, it can not be adequately assessed clinically.

Table 4. Honey for wound treatment.

| Year | Intervention | N | Wound type | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| 2006 (e55) |

Manuka honey– alginate dressing vs Jelonet from postoperative day 2 onward |

100 | Acute | Toenail surgery | RCT, Q good | Healing after partial toenail removal (honey vs Jelonet): 32 vs 20 days (p = 0.01); no difference after total removal |

| 2016 (e32) |

Postoperative oral treatment with honey vs placebo |

264 | Acute | Tonsillectomy | SR, Q moderate | Pain: day 1 (SMD = −1.39; p = 0.03); day 5 (SMD = −0.31; p = 0.03) Use of anesthesia: day 1 (SMD = −0.93; p <0.01), day 3 (smd = −0.93; p <0.01), day 5 (smd = −1.12; p <0.01) wound healing: day 1 (smd = 0.86; p = 0.04), day 4 (smd = 0.86; p = 0.05), day 7 (smd = 1.13; p = 0.05), and day 14 (smd = 0.61; p = 0.03) |

| 2015 (e34) |

Honey vs other wound dressings |

213 | Acute | Minor surgery | SR, Q high | Not assessable due to poor quality of the studies included in the systematic review |

| 2015 (e34) |

Honey vs washes (alcohol/iodine) |

50 | Infected, postoperative wound |

Cesarean, hysterectomy |

SR, Q high | Moderate evidence for honey: RR = 1.7 (95% CI: [1.1; 2.6]) |

* The complete table is available on the internet as eTable 4

CI, confidence interval; N, sample size; Q, quality determined by AMSTAR score (for SR) or by Jadad score (for RCTs); RCT, randomized controlled trial

RR, relative risk; SMD, standardized mean difference; SR, systematic review

eTable 4. Honey for wound treatment.

| Reference*1 | Year | Intervention | N*4 | Wound type*4 | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| (e55) | 2006 | Manuka honey–alginate dressing vs Jelonet on 2nd postoperative day | 100 | Acute | Toenail surgery | RCT, quality*2: good |

Complete healing after partial toenail removal (honey vs Jelonet): 32 vs 20 days (P = 0.01); no difference after total removal |

| (e59) | 2005 | Honey dressing vs EUSOL (chlorinated lime and boric acid), twice daily for three weeks |

43 | Acute infected (abscess) | None | RCT, quality*2: bad |

Wound on day 7 (honey vs EUSOL): clean and dry, 100% vs 66% (P < 0.01); granulation tissue, 100% vs 50% (p < 0.01); epithelialization, 87% vs 35% (P = 0.001); completion of epithelialization on day 21, 87% vs 55% (P = 0.05); duration of hospital stay: 16.08 vs 18.61 days (P = 0.02) |

| (e32) | 2016 | Postoperative oral treatment with honey vs placebo | 264 | Acute | Tonsillectomy | Systematic review, quality*3: moderate |

Pain on day 1 (SMD = −1.39; P = 0.03) and day 5 (SMD = −0.31; P = 0.03); use of anesthesia on day 1 (SMD = −0.93; P < 0.01), day 3 (smd = −0.93; p < 0.01), and day 5 (smd = −1.12; p < 0.01); wound healing on day 1 (SMD = 0.86; P = 0.04), day 4 (SMD = 0.86; P = 0.05), day 7 (SMD = 1.13; P = 0.05), and day 14 (SMD = 0.61; P = 0.03) |

| (e34)*4 | 2015 | Honey vs other wound dressings | 213 | Acute | Minor surgery | Systematic review, quality*3: high |

Not assessable due to poor quality |

| (e34)*4 | 2015 | Honey vs washes (alcohol and povidone-iodine) | 50 | Infected postoperative wounds | C-section, hysterectomy | Systematic review, quality*3: high |

Moderate evidence for honey: RR = 1.7 (95% CI: [1.1; 2.6]) |

*1 See eReferences; *2 Calculated according to the Jadad score; *3 Calculated according to the AMSTAR score *4 Results given separately as they represent distinct wound types

CI, confidence interval; EUSOL, Edinburgh University Solution of Lime; N, sample size; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, relative risk; SMD, standardized mean difference

Wound healing and and healing of colorectal anastomosis seem to be influenced by the composition of the gut microbiome (7, 8). Controlled studies have shown clear indications in humans that the intestinal microbiome changes postoperatively (9); in particular, levels of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria appear to decrease. A 2013 meta-analysis (13 RCTs, 962 patients) of moderate quality found that probiotics significantly reduced the rate of septic complications after general surgery (10). However, the optimal composition and dosage of probiotics remains to be determined. Furthermore, the extent to which the intestinal microbiome is causally involved in postoperative complications in humans is still not clear.

Postoperative pain

Studies on CAM for postoperative pain have been most frequently carried out for acupuncture and acupressure. The results are listed in Table 1 and eTable 1. Six of the ten systematic reviews reported a reduced perception of pain or a reduced need for analgesics in patients treated with acupuncture or acupressure. Two further reviews stated that they could not comment on the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment due to a small sample size or inhomogeneous data.

Aromatherapy seems to offer another option for pain relief. The results of recent studies are shown in Table 2 and eTable 2. Eight studies were identified (including seven RCTs). Due to the lack of blinding in these studies, their methodological quality is predominantly rated as poor by the Jadad scoring system (see eMethods). But it must be emphasized that it is difficult to blind a study on aromatherapy. Five of the eight studies reported significant improvement after aromatherapy. The aroma was mostly lavender. In principle, aromatherapy offers a number of advantages: it is inexpensive, available without prescription, has no risk of addiction, has a low side-effect profile (after allergies have been excluded), and can be independently used and modulated by the patient depending on the application system.

Whether music therapy can have pain-reducing effects was examined in two systematic reviews, which were of good and moderate quality. Both reviews reported a reduction in pain perception (Table 5, eTable 5).

Table 5. Perioperative and postoperative music therapy*.

| Year | Intervention | N | Patients | Surgery | Type/quality | Results |

| Symptom: Anxiety, stress, and sleep disturbances | ||||||

| 2013 (e18) |

Perioperative: music | 955 | Adults | Cardiac surgery/ intervention |

SR, Q high | Stress reduction: WMD = −1.26 (95% CI: [−2.30; −0.22], p = 0.02); anxiety: SMD = −0.70 (95% CI: [−1.17, −0.22], p <0.01); quality of sleep: smd = 0.91 (95% ci: [0.03; 1.79], p = 0.04) |

| 2013 (e19) |

Preoperative: music | 2051 | Adults | Mixed | SR, Q high | Anxiety: −5.72 pts (95% CI: [−7.27; −4.17], p <0.01 |

| 2015 (e66) |

Music vs other procedure or standard |

781 | Women | Gynecologic | SR, Q moderate | One study each showed a significant reduction of anxiety or fatigue, respectively |

| 2015 (e29) |

Postoperative: music | 630 | Children/ youth up to 18 years old |

Orthopedic, cardiac, and ambulatory |

SR, Q high | Anxiety: SMD = −0.34 (95% CI: [−0.66; −0.01]) Stress: SMD = −0.50 (95% CI: [−0.84; −0.16]) |

| 2015 (e4) |

Music vs midazolame | 123 | Children up to 7 years |

Ambulatory surgery | SR, Q high | Significantly better anxiety reduction with midazolame than with music therapy (p = 0.02) |

| Symptom: Pain | ||||||

| 2015 (e66) |

Music vs other procedure or standard |

781 | Women | Gynecologic | SR, Q moderate | Significant reduction of pain (in five of seven studies) and of need for anesthesia (in one study) |

| 2015 (e29) |

Postoperative: music | 630 | Children/youth up to 18 years old |

Mixed | SR, Q high | Pain: SMD = −1.07 (95% CI: [−2.08; −0.07]) |

* The complete table is available in the eMethods

CI, confidence interval; N, sample size; pts, points; Q, quality determined by AMSTAR score; SMD, standardized mean difference; SR, systematic review; WMD, weighted mean difference

eTable 5. Perioperative and postoperative music therapy.

| Reference*1 | Year | Intervention | N*2 | Patients*2 | Surgery*2 | Type/quality*3 | Results |

| Symptom: Anxiety, stress and sleep disturbances | |||||||

| (e18) | 2013 | Music therapy before, during, and after intervention, using different lengths and types, vs no intervention | 955 | Adults | Cardiac surgery/ intervention |

Systematic review, quality: high |

Stress reduction: MD = −1.26 (95% CI: [−2.30; −0.22], p = 0.02); anxiety: SMD = −0.70 (95% CI: [−1.17, −0.22], p <0.01); quality of sleep: smd = 0.91 (95% ci: [0.03; 1.79], p = 0.04, n = 122) |

| (e19) | 2013 | Preoperative music therapy (mostly around 30 min and by patient's choice) | 2051 | Adults | Mixed | Systematic review, quality: high |

Anxiety: −5.72 pts in STAI (95% CI: [−7.27; −4.17], p < 0.01) as well as −0.6 pts on other standardized anxiety scales (95% ci: [−0.9; −0.31], p <0.01) |

| (e66) | 2015 | Music therapy (relaxing or by patient's choice) vs other procedure or no intervention | 781 | Women | Gynecologic | Systematic review, quality: moderate | One study each showed a significant reduction of anxiety or fatigue, respectively |

| (e29) | 2015 | Postoperative music therapy (immediately after surgery, for 30–45 min) |

630 | Children/ youth up to 18 years old |

Orthopedic, cardiac, and ambulatory surgery | Systematic review, quality: high | Anxiety: SMD = −0.34 (95% CI: [−0.66; −0.01]) Stress: SMD = −0.50 (95% CI: [−0.84; −0.16]) |

| (e4) | 2015 | Music during induction of anesthesia vs midazolame | 123 | Children up to 7 years old | Ambulatory surgery | Systematic review, quality: high | Midazolame was significantly better than music therapy for anxiety reduction (p = 0.02) |

| Symptom: Pain | |||||||

| (e66) | 2015 | Music therapy (relaxing or by patient's choice) vs other procedure or no intervention | 781 | Women | Gynecologic | Systematic review, quality: moderate | Significant reduction of pain (in five of seven studies) and of need for anesthesia (in one study) |

| (e29) | 2015 | Postoperative music therapy (immediately after surgery; for 30–45 min) | 630 | Children/youth up to 18 years old | Orthopedic, cardiac, and ambulatory surgery | Systematic review, quality: high | Pain: SMD = −1.07 (95% CI: [−2.08; −0.07]) |

*1 See eReferences; *2 Refers only to patients who were enrolled in studies on music therapy; *3 Calculated according to the AMSTAR score

CI, confidence interval; MD, mean deviation; N, sample size; pts, points; SMD, standardized mean difference; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

A further study, which was however non-controlled and of poor methodological quality, examined an extensive, multimodal, and holistic approach to reducing pain that consisted of multiple preoperative interviews and a combination of several of the therapies mentioned above (11). Even though the study found a significant reduction in pain (of –1.19 points, on a scale of 1 to 10, p<0.001), it is not very meaningful for everyday clinical practice due to methodological shortcomings and a questionable feasibility (as it carries high financial and time expenses).

Sleep disturbances, stress-related symptoms, and postoperative recovery

Depending on the type and extent of surgery, surgical interventions lead to a stress reaction that can become an independent problem in a post-aggression catabolic metabolism (12, 13). A simple and cost-effective way to reduce sympathicotonia and thus reduce sleep onset latency is to apply heat to the extremities (14, 15). Phytotherapeutically, lavender, valerian, and hops (humulus) are used in restlessness and sleep disturbances, although none of the preparations have been validly analyzed for treating surgical patients. At present there are only two RCTs of good quality that have addressed the effectiveness of valerian in surgical patients (Table 3, eTable 3). In the first study, a preoperative dose of valerian was tested for reducing anxiety in patients about to undergo wisdom tooth surgery. In the second study, the effect of valerian on the development of cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery was examined (Table 3, eTable 3). In both studies, valerian was found to have a positive effect. The efficacy of finished preparations containing lavender, valerian, or hops for sleep disturbances can not be determined due to lack of studies.

Acupuncture and acupressure are also used in CM/NT to reduce stress and anxiety as well as to improve sleep. Two systematic reviews (of high and moderate quality) have examined these for surgical patients, and both report reduction in anxiety (Table 1, eTable 1).

Seven studies (including five RCTs) examined the efficacy of aromatherapy in reduction of stress and anxiety related to surgery (Table 2, eTable 2). Four studies showed a positive effect from aromatherapy, although only one study was of good methodological quality. Both studies that addressed improving sleep showed a positive, significant effect; however, both were rated to be of poor quality, as they were non-controlled experimental studies. Overall, it is therefore difficult to make a final assessment. None of the studies shown in Table 2 or eTable 2 reported any impact on physical parameters, such as blood pressure or heart rate (data not shown).

The effectiveness of the therapeutic use of music to reduce anxiety and stress associated with surgery was analyzed in five systematic reviews of predominantly high quality, in both children and adults. Four out of five systematic reviews found a positive effect for this (Table 5, eTable 5). Only one review that assessed the anxiety of children (younger than 7 years of age) prior to anesthesia induction found that treatment with midazolame led to a greater reduction of anxiety than music (e4).

Concepts such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) have already been used successfully in the area of oncology, among others (16). This systematic search did not find studies testing MBSR or any other form of mind body medicine (MBM) for surgical patients. MBM serves the biopsychosocial strengthening of personal coping resources, in order to give the patient more autonomy and responsibility in dealing with illness. The success of such strategies has been shown in surgery in recent years. Approaches such as the Fast Track (FT) program or the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program include elements of modern mind body medicine (17, 18). Patients are taught by the surgeon that they are an “active part” of the recovery process. Through a willingness to mobilize and to early normal food intake, the person concerned can actively contribute to the improvement of his or her state of health (19, 20). The contribution of the psyche to the success of FT and ERAS should be examined in more detail in the future.

Postoperative recovery may also be positively influenced by acupuncture, as reported by Asmussen et al. in two systematic reviews of moderate quality (e5, e6). For both cardiac and neurosurgical patients, they concluded that acupuncture treatment is likely to result in a more rapid recovery (Table 1, eTable 1).

Risks of naturopathic treatment and complementary medicine

None of the research documented any serious side effects for the methods used. The safety of acupuncture in routine medical care has been studied in Germany in more than 300 000 patients, with only 0.8% of the patients experiencing side effects requiring treatment (21).

Herbal preparations can be a safety hazard in everyday clinical practice, as they are often taken by patients without consulting a physician (1, 3). Some substances, such as St. John’s wort, have a significant interaction risk (22, 23). For instance, substances such as cranberry are suspected of increasing the risk of bleeding (24). Although the risk may be very low, perioperative uncertainties persist. Phytotherapeutic drugs should therefore be discontinued prior to major surgery for safety reasons.

Conclusion

CM/NT offer a wide range of possible supportive therapy options. So far, however, only a few measures have been investigated in surgically-treated patients. The use of acupuncture and acupressure has been evaluated in numerous studies for postoperative nausea and vomiting and pain therapy and has been shown to alleviate symptoms. Although recent studies show that ginger can accelerate gastric emptying, they could not establish it as a drug for prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting. The effectiveness of phytotherapeutics, such as valerian, hops, and lavender, at reducing anxiety and sleep disturbances of surgical patients can still not be determined with certainty from the current study situation. Non-pharmacological procedures, such as music therapy, have been shown by several studies to alleviate restlessness, stress, anxiety, and pain, both preoperatively and postoperatively. Relaxation techniques and mindfulness-based therapies have not been studied for surgical patients. It also remains unclear whether treatment with honey or other plant-based substances has a positive effect on healing of infected wounds. Finally, research on the roles that the gut microbiome plays in helping to prevent postoperative complications, and its modulation by probiotics, is still in its infancy.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODs

This review was carried out as a joint project of the Center for Complementary Medicine and the Department for General and Visceral Surgery of the Medical Center, University of Freiburg. Initially, an evaluation of the typical postoperative problems was carried out by all authors (ebox). Based on the clinical and scientific experience of two authors (AKL and RH), potentially suitable complementary medical procedures for treatment were defined for the systematic search (eBox „Keywords“).

The systematic literature review and evaluation were carried out according to the PRISMA guidelines by two authors (AKL and RH) via Medline (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), the Cochrane Library (cochranelibrary.com), and WebOfScience (webofknowledge.com). For evaluation, only articles in English, German, Spanish, French, Italian, or Greek were considered. As determined before beginning search, the title or abstract of appropriate articles had to be related to acute treatment in surgery (for all areas of surgery, including specialty disciplines, such as ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology) and complementary medicine, as well the specified keywords. No restrictions were made regarding age, sex, or origin of patients. The search did not include studies comparing surgical and conventional therapy, or burns or wounds due to malignant, metabolic, or vascular diseases. The first search step looked for systematic reviews. In cases where the systematic reviews that were retrieved had different overall objectives (i.e., not in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review), any appropriate studies from the reference list were used to evaluate this review. If no systematic reviews were retrieved, a search for randomized controlled trials, controlled trials, and experimental studies on humans was carried out. All results were evaluated for inclusion by title and abstract.

Study logs, non-systematic summaries, and outdated versions of reviews that already had an update were not used for evaluation.

The quality assessment of the included publications was done by a scoring system. The modified German version of the AMSTAR score (e76) was used for systematic reviews, and the Jadad score, for clinical trials (e77). The German version of the AMSTAR score examines over eleven different questions that evaluate the planning of the review, the search strategy, the bias risk, conflicts of interest, the quality of systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. The maximum score is 11 points, with a score of 9–11 considered as high, 5–8 as moderate, and 0–4 as low. The Jadad score is a validated questionnaire that evaluates clinical intervention studies and assesses randomization, blinding, and dropout rates. It consists of five questions, with a maximum score of 5 points; a study is rated as “good” if it has a value of 3 or higher.

The article section “Risks of naturopathic treatment and complementary medicine” is based on a selective literature search by the two naturopathic authors and thus represents an expert opinion.

Key Messages.

Basic knowledge of complementary medicine and naturopathic treatments is relevant for all clinically active physicians.

Acupuncture and acupressure can reduce perioperative anxiety and have a positive effect on postoperative pain, nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal dysfunction.

There is evidence that perioperative music therapy can reduce anxiety, stress and pain.

Mind body medicine, with respect to strengthening patient self-management, is now part of established pre- and postoperative surgical programs.

The safety of most naturopathic and complementary treatments has been confirmed, although uncertainties still exist regarding interactions of phytotherapeutic drugs.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr. Veronica A. Raker

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Wortmann JK, Bremer A, Eich H, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer: a cross-sectional study at different points of cancer care. Med Oncol. 2016;33 doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schieman C, Rudmik LR, Dixon E, Sutherland F, Bathe OF. Complementary and alternative medicine use among general surgery, hepatobiliary surgery and surgical oncology patients. Can J Surg. 2009;52:422–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soós SÁ, Jeszenoi N, Darvas K, Harsányi L. Nem konvencionális gyógymódok használata sebészeti betegek között. Orv Hetil. 2016;157:1483–1488. doi: 10.1556/650.2016.30543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pertz H, Lehmann J, Roth-Ehrang R, Elz S. Effects of ginger constituents on the gastrointestinal tract: role of cholinergic M 3 and serotonergic 5-HT 3 and 5-HT 4 receptors. Planta Med. 2011;77:973–978. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sipos P, Gyõry H, Hagymási K, Ondrejka P, Blázovics A. Special wound healing methods used in ancient Egypt and the mythological background. World J Surg. 2004;28:211–216. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das U, Behera SS, Pramanik K. Ethno-herbal-medico in wound repair: an incisive review. Phyther Res. 2017;31:579–590. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krezalek MA, Alverdy JC. The role of the microbiota in surgical recovery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:347–352. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alverdy JC, Hyoju SK, Weigerinck M, Gilbert JA. The gut microbiome and the mechanism of surgical infection. Br J Surg. 2017;104:e14–e23. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lederer AK, Pisarski P, Kousoulas L, Fichtner-Feigl S, Hess C, Huber R. Postoperative changes of the microbiome: are surgical complications related to the gut flora? A systematic review. BMC Surg. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0325-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinross JM, Markar S, Karthikesalingam A, et al. A meta-analysis of probiotic and synbiotic use in elective surgery. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2013;37:243–253. doi: 10.1177/0148607112452306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sears SR, Bolton S, Bell HKL. Evaluation of “Steps to Surgical Success” (STEPS) pain and anxiety related to surgery. 2013;6:349–357. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3182a72c5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartl WH, Jauch KW. [Post-aggression metabolism: attempt at a status determination] Infusionsther Transfusionsmed. 1994;21:30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hölscher AH, Siewert JR. Pathophysiologische Folgen, Vorbehandlung und Nachbehandlung bei operativen Eingriffen und Traumen Chirurgie. In: Siewert JR, Stein HJ, editors. Springer. Berlin, Heidelberg: 2012. pp. 1–185. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tansey EA, Roe SM, Johnson CD. The sympathetic release test: a test used to assess thermoregulation and autonomic control of blood flow. AJP Adv Physiol Educ. 2014;38:87–92. doi: 10.1152/advan.00095.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kräuchi K, Cajochen C, Werth E, Wirz-Justice A. Warm feet promote the rapid onset of sleep. Nature. 1999;401:36–37. doi: 10.1038/43366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledesma D, Kumano H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: a meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2009;18:571–579. doi: 10.1002/pon.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwenk W. Fast-Track: Evaluation eines neuen Konzeptes. Der Chirurg. 2012;83:351–355. doi: 10.1007/s00104-011-2226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, Gemma M, Pecorelli N, Braga M. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014;38:1531–1541. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwenk W. Fast-track-Rehabilitation in der Viszeralchirurgie. Der Chirurg. 2009;80:690–701. doi: 10.1007/s00104-009-1676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Schwenk W, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations. World J Surg. 2013;37:259–284. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witt CM, Brinkhaus B, Jena S, Selim D, Straub C, Willich SN. Wirksamkeit, Sicherheit und Wirtschaftlichkeit der Akupunktur Ein Modellvorhaben mit der Techniker Krankenkasse. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103 A:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber R, Michalsen A. Haug Verlag. 1. Vol. 800. Stuttgart: 2014. Checkliste Komplementärmedizin. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208–216. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammed Abdul MI, Jiang X, Williams KM, et al. Pharmacodynamic interaction of warfarin with cranberry but not with garlic in healthy subjects. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;154:1691–1700. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Hines S, Steels E, Chang A, Gibbons K. Aromatherapy for treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2018;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007598.pub3. CD007598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Gabrielli F, Macchini D, Guttadauro A, et al. Psyllium fiber vs placebo in early treatment after STARR for obstructed defecation: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Minerva Chir. 2016;71:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Crocetti D, Velluti F, La Torre V, Orsi E, De Anna L, La Torre F. Psyllium fiber food supplement in the management of stoma patients: results of a comparative prospective study. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:595–596. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-0983-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Manyande A, Cyna AM, Yip P, Chooi C, Middleton P. Non-pharmacological interventions for assisting the induction of anaesthesia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006447.pub3. CD006447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Asmussen S, Maybauer DM, Chen JD, et al. Effects of acupuncture in anesthesia for craniotomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2017;29:219–227. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Asmussen S, Przkora R, Maybauer DM, et al. Meta-analysis of electroacupuncture in cardiac anesthesia and intensive care. J Intensive Care Med. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0885066617708558. 088506661770855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Adachi N, Munesada M, Yamada N, et al. Effects of aromatherapy massage on face-down posture-related pain after vitrectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Hosseini FS. Investigating the effects of inhaling ginger essence on post-nephrectomy nausea and vomiting. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:827–831. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Anderson LA, Gross JB. Aromatherapy with peppermint, isopropyl alcohol, or placebo is equally effective in relieving postoperative nausea. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004,;19:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Arfeen Z, Owen H, Plummer JL, Ilsley AH, Sorby-Adams RA, Doecke CJ. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of ginger for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1995;23:449–452. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9502300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Ashrastaghi O, Ayasi M, Gorji MH, Habibi V, Yazdani J, Ebrahimzadeh M. The effectiveness of lavender essence on strernotomy related pain intensity after coronary artery bypass grafting. Adv Biomed Res. 2015;4 doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.158050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Au DWH, Tsang HWH, Ling PPM, Leung CHT, Ip PK, Cheung WM. Effects of acupressure on anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. 2015;33:353–359. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2014-010720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Ayik C, Özden D. The effects of preoperative aromatherapy massage on anxiety and sleep quality of colorectal surgery patients: a randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Med. 2018;36:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Bameshki A, Namaiee MH, Jangjoo A, et al. Effect of oral ginger on prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Electron physician. 2018;10:6354–6362. doi: 10.19082/6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Barlow T, Downham C, Barlow D. The effect of complementary therapies on post-operative pain control in ambulatory knee surgery: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Ljunggreen AE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can reduce postoperative analgesic consumption A meta-analysis with assessment of optimal treatment parameters for postoperative pain. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:181–188. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Bone ME, Wilkinson DJ, Young JR, McNeil J, Charlton S. Ginger root—a new antiemetic The effect of ginger root on postoperative nausea and vomiting after major gynaecological surgery. Anaesthesia. 1990;45:669–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Bradt J, Dileo C, Potvin N. Music for stress and anxiety reduction in coronary heart disease patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006577.pub3. CD006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Bradt J, Dileo C, Shim M. Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006908.pub2. CD006908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Cheong KB, Zhang J, Huang Y. The effectiveness of acupuncture in postoperative gastroparesis syndrome—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:767–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Cheong KB, Zhang J, Huang Y, Zhang Z. The effectiveness of acupuncture in prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082474. e82474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Cho YH, Kim CK, Heo KH, et al. Acupuncture for acute postoperative pain after back surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Pract. 2015;15:279–291. doi: 10.1111/papr.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Eberhart LHJ, Mayer R, Betz O, et al. Ginger does not prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:995–998. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000055818.64084.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Fayazi S, Babashahi M, Rezaei M. The effect of inhalation aromatherapy on anxiety level of the patients in preoperative period. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011;16:278–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Ferruggiari L, Ragione B, Rich ER, Lock K. The effect of aromatherapy on postoperative nausea in women undergoing surgical procedures. J Perianesth Nurs. 2012;27:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Griffiths JD, Gyte GM, Paranjothy S, Brown HC, Broughton HK, Thomas J. Interventions for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007579.pub2. CD007579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Hadi N, Hanid AA. Lavender essence for post-cesarean pain. Pak J Biol Sci. 2011;14:664–667. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2011.664.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Hassani S, Alipour A, Darvishi Khezri H, et al. Can valeriana officinalis root extract prevent early postoperative cognitive dysfunction after CABG surgery? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:843–850. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.van der Heijden MJE, Oliai Araghi S, van Dijk M, Jeekel J, Hunink MGM. The effects of perioperative music interventions in pediatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133608. e0133608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Hodge NS, McCarthy MS, Pierce RM. A prospective randomized study of the effectiveness of aromatherapy for relief of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2014;29:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Hunt R, Dienemann J, Norton HJ, et al. Aromatherapy as treatment for postoperative nausea: a randomized trial. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:597–604. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824a0b1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Hwang SH, Song JN, Jeong YM, Lee YJ, Kang JM. The efficacy of honey for ameliorating pain after tonsillectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:811–818. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.de Jong M, Lucas C, Bredero H, van Adrichem L, Tibboel D, van Dijk M. Does postoperative “M” technique massage with or without mandarin oil reduce infants’ distress after major craniofacial surgery? J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:1748–1757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Jull AB, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Westby MJ, Deshpande S, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005083.pub4. CD005083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Kalava A, Darji SJ, Kalstein A, Yarmush JM, SchianodiCola J, Weinberg J. Efficacy of ginger on intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting in elective cesarean section patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio. 2013;169:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Özlü ZK, Bilican P. Effects of aromatherapy massage on the sleep quality and physiological parameters of patients in a surgical intensive care unit. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2017;14:83–88. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Kiberd MB, Clarke SK, Chorney J, D’Eon B, Wright S. Aromatherapy for the treatment of PONV in children: a pilot RCT. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Kim JT, Ren CJ, Fielding GA, et al. Treatment with lavender aromatherapy in the post-anesthesia care unit reduces opioid requirements of morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2007;17:920–925. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Kim JT, Wajda M, Cuff G, et al. Evaluation of aromatherapy in treating postoperative pain: pilot study. Pain Pract. 2006;6:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Kim KH, Kim DH, Kim HY, Son GM. Acupuncture for recovery after surgery in patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. 2016;34:248–256. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]