Abstract

Cytochrome c (cyt c) is a small hemoprotein involved in electron shuttling in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and is now also recognized as an important mediator of apoptotic cell death. Its role in inducing programmed cell death is closely associated with the formation of a complex with the mitochondrion-specific phospholipid cardiolipin (CL), leading to a gain of peroxidase activity. However, the molecular mechanisms behind this gain and eventual cyt c autoinactivation via its release from mitochondrial membranes remain largely unknown. Here, we examined the kinetics of the H2O2-mediated peroxidase activity of cyt c both in the presence and absence of tetraoleoyl cardiolipin (TOCL)- and tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin (TLCL)-containing liposomes to evaluate the role of cyt c–CL complex formation in the induction and stimulation of cyt c peroxidase activity. Moreover, we examined peroxide-mediated cyt c heme degradation to gain insights into the mechanisms by which cyt c self-limits its peroxidase activity. Bottom-up proteomics revealed >50 oxidative modifications on cyt c upon peroxide reduction. Of note, one of these by-products was the Tyr-based “cofactor” trihydroxyphenylalanine quinone (TPQ) capable of inducing deamination of Lys ϵ-amino groups and formation of the carbonylated product aminoadipic semialdehyde. In view of these results, we propose that autoinduced carbonylation, and thus removal of a positive charge in Lys, abrogates binding of cyt c to negatively charged CL. The proposed mechanism may be responsible for release of cyt c from mitochondrial membranes and ensuing inactivation of its peroxidase activity.

Keywords: cytochrome c, cardiolipin, peroxidase, mitochondria, apoptosis, proteomics, carbonylation, lipid hydroperoxides, oxidation, peroxidase activity, self-inactivation, auto-inactivation

Introduction

Cytochrome c (cyt c)4 was originally identified as an electron shuttle within the respiratory chain, essentially contributing to the aerobic pathway of oxidative phosphorylation. However, the single-chain hemoprotein is nowadays also known as a key mediator of apoptosis (1), making cyt c an important cornerstone of the cell fate. Upon apoptosis induction, the protein is released from the inner membrane space of the mitochondria to the cytosol where it binds to apoptosis-activating factor 1 (2), leading to caspase-9 activation (3) and subsequently apoptosis. Thereby, cyt c seems to actively contribute to this process, although the exact biochemical mechanisms for its release from the mitochondria are still under discussion.

Although cyt c–mediated pore formation leading to outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization was suggested (4), others did not observe a considerable unfolding and/or insertion of the protein into the outer mitochondrial membrane (5, 6). Another mechanism proposed by Kagan et al. (7) links the release of cyt c at the early stage of apoptosis to the gain of a peroxidase activity by this protein. Cyt c binds to cardiolipin (CL), a mitochondrion-specific phospholipid, which redistributes from the inner to the outer mitochondrial membrane upon apoptosis onset (8–10). This complex formation results in structural modifications of the protein that trigger a strong peroxidase activity in the presence of H2O2 (11, 12), leading to a specific oxidation of the polyunsaturated fatty acyl chains in CL (7, 12, 13), thus causing permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane and the release of cyt c and other proapoptotic factors (8, 13). Both a cyt c–CL complex formation and a high cyt c–based peroxidase activity were observed during early apoptosis (7). The mitochondrial concentration of H2O2 also increases upon apoptosis onset, reaching submillimolar levels (14). In vitro experiments with liposomes confirmed the permeabilization of CL-containing lipid membranes via the described processes (15, 16). Thus, the formation of cyt c–CL complexes triggers a functional shift of the protein function from electron transport to peroxidase activity (9), which, via CL oxidation, contributes to the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (5, 8, 17).

As it was highlighted by Kagan et al. (9), the fatty acid composition of CL species influences the binding and subsequent unfolding of cyt c. Furthermore, CL acts not only as a passive template for the induction of peroxidase activity in cyt c but actively provides substrates for its enzymatic activity. CL-induced peroxidase activity of cyt c leads to lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) formation in CL, which further promotes its enzymatic activity as well as the subsequent release of cyt c from the mitochondria (7, 18). However, it remains to be clarified whether pre-existing lipid hydroperoxides in CL may be sufficient to initiate the proposed autocatalytic cycle or whether H2O2 is still mandatory for the cyt c peroxidase-derived permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane upon apoptosis induction (19).

Several studies report an increased degradation of cyt c upon complex formation with CL (20), most likely due to H2O2-mediated heme degradation and subsequent iron release (8, 21, 22). Cyt c oxidative modifications were also observed in the absence of CL after incubating the protein with H2O2 (21, 23). Thereby, both cyt c–derived peroxidase activity and Fenton chemistry were described as possible oxidative pathways, suggesting that peroxidase activity of cyt c and a subsequent heme degradation may be interlinked (24). It remains unclear whether CL-dependent degradation of the protein is a result of its peroxidase activity and subsequent heme degradation by released radical by-products.

Here, we examined the kinetics of the H2O2-mediated peroxidase activity of cyt c both in the absence and presence of CL-containing liposomes to evaluate the role of cyt c–CL complex formation in the induction and promotion of its enzymatic activity. Thereby, the role of the CL fatty acyl chains was also considered, thus expanding comparable recent studies (25). Subsequent heme degradation in cyt c was evaluated to gain insights into the self-limiting mechanisms occurring during the cyt c–based peroxidase activity, providing a basis for free radical chemistry. Furthermore, over 50 oxidative modifications of cyt c resulting from the enzymatic activity of cyt c–CL complexes were studied using a bottom-up proteomics approach, and a new mechanism of autocatalyzed cyt c carbonylation via Tyr-derived cofactor leading to the reduction of protein positive charge and dissociation of cyt c–CL complex was proposed.

Results

H2O2- and cardiolipin-dependent peroxidase activity of cytochrome c

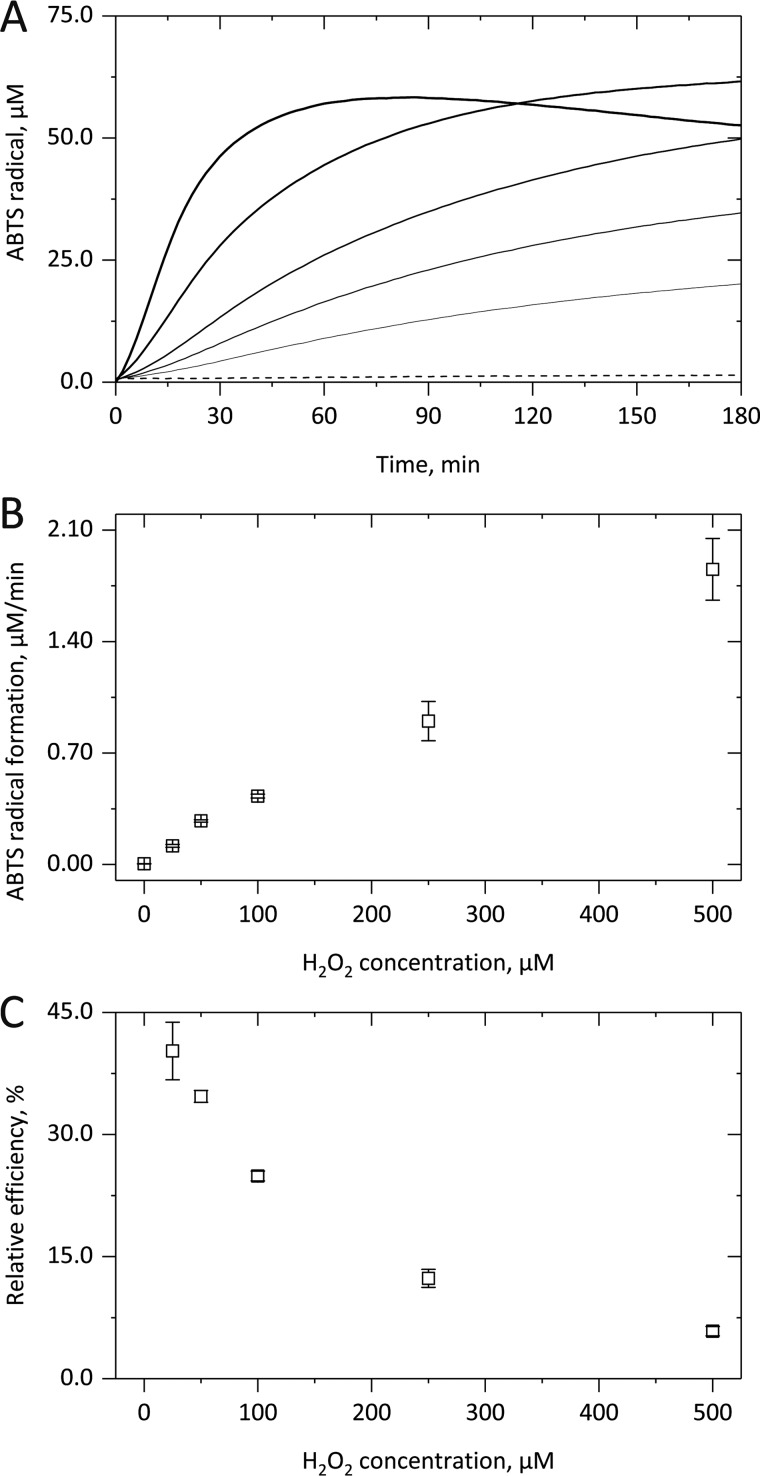

We first performed kinetic measurements to investigate cyt c–based peroxidase activity in the sole presence of H2O2. The averaged kinetic curves (Fig. 1A) clearly show a time-dependent 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) radical formation upon addition of increasing H2O2 concentrations (straight lines). Three different kinetic phases were observable, namely a lag phase with low enzymatic activity, a subsequent steady-state phase of constant ABTS oxidation followed by a complete cease of the peroxidase activity. Thereby, at higher H2O2 concentrations (bolder lines), shorter lag phases, higher steady-state enzyme activities, and a quicker deactivation of the latter were observed, apparently also leading to lower ABTS radical yields. In the absence of H2O2 (dashed line) or cyt c (not shown), no ABTS oxidation took place. Thus, H2O2 activates and promotes cyt c–based peroxidase activity but subsequently also leads to its autocatalytic limitation.

Figure 1.

H2O2-dependent peroxidase activity of cytochrome c. After adding up to 500 μm H2O2 to 5 μm cyt c, the formation of ABTS+• from 1 mm ABTS in 10 mm PB, pH 7.4, was followed for up to 3 h at 37 °C by monitoring the absorbance increase at 734 nm. The kinetic curves in A illustrate that in the presence of increasing H2O2 concentrations (straight lines; 25, 50, 100, 250 and 500 μm) a shorter lag phase, a higher linear ABTS+• formation rate, and a quicker deactivation of the cyt c–based peroxidase activity were observed. In B, the linear increase of the cyt c–derived enzymatic activity with H2O2 concentration is shown. In C, the coinciding exponential decrease in the relative efficiency of the cyt c-derived peroxidase activity is illustrated. In A, averaged kinetic curves from three independent experiments are shown; in B and C, the corresponding mean (points) and S.D. (error bars) values are given.

A replot of the steady-state ABTS radical formation rate against the applied amount of H2O2 (Fig. 1B) showed a linear concentration dependence, which indicates pseudo-first order reaction conditions and translates to a kobs value of 6.0 ± 0.5 m−1 s−1 (Fig. 2B). By comparing the obtained ABTS radical yield with the applied H2O2 concentration, the relative efficiency of the cyt c–based peroxidase activity was also calculated, again assuming formation of two ABTS radicals per peroxidase cycle. However, even at 25 μm H2O2, only the formation of 20.13 μm ABTS radicals was observed, corresponding to a relative yield of 40.3 ± 3.5%. With increasing hydrogen peroxide concentrations, this value considerably decreased (Fig. 1C). Thus, a strong H2O2-mediated promotion of cyt c–based peroxidase activity translates to lower relative enzymatic efficiencies due to quick enzyme inactivation.

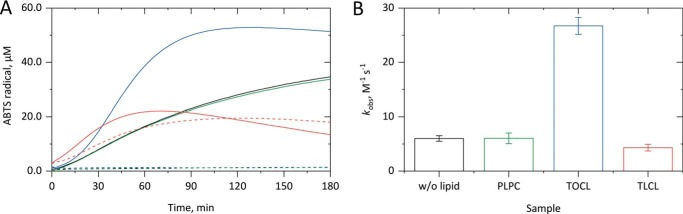

Figure 2.

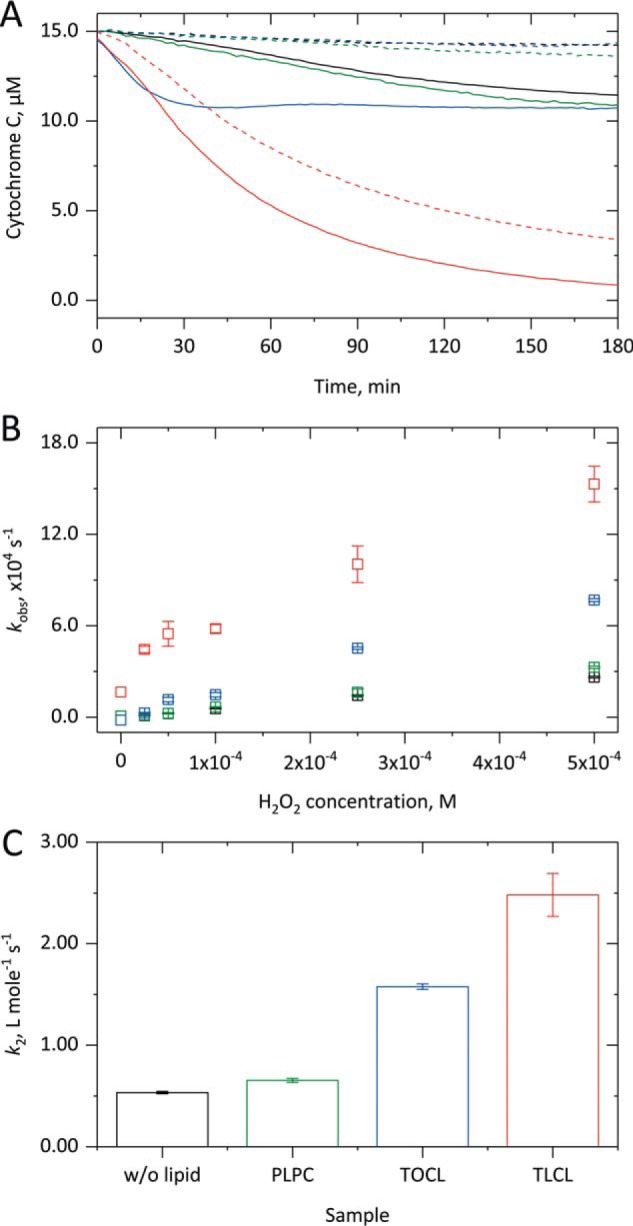

Effect of cardiolipin on cytochrome c peroxidase activity. After preincubating 5 μm cyt c in 10 mm PB, pH 7.4, with liposomes (500 μm lipid concentration) in 10 mm PB, pH 7.4, 50 μm H2O2 was added, and the formation of ABTS+• from 1 mm ABTS was followed for up to 3 h at 37 °C by monitoring the absorbance increase at 734 nm. The kinetic curves in A show that PLPC (green) has no effect on the cyt c–based peroxidase activity either in the presence (straight line) or in the absence (dashed line) of H2O2. TOCL (blue) strongly promotes the H2O2-derived cyt c–based peroxidase activity. TLCL (red) also supports the H2O2-derived cyt c peroxidase activity promotion but also activates this enzymatic activity on its own. In B, the H2O2-derived increase in the peroxidase activity of cyt c is shown for the lipid-free system (black) as well as for liposomes with the named lipids. In A, averaged kinetic curves from three independent experiments are shown; in B, the corresponding mean (columns) and S.D. (error bars) values are given.

We next tested whether the presence of CL influences the H2O2-dependent peroxidase activity of cyt c by applying large unilamellar vesicle (LUV) liposomes with different lipid compositions. The kinetic measurements (Fig. 2A) clearly showed that both in the absence (black) and in the presence of tetraoleoyl cardiolipin (TOCL)-containing liposomes (blue) no cyt c–based peroxidase activity was observed in the absence of H2O2 (dashed lines), but TOCL strongly promoted the cyt c enzymatic activity in the presence of H2O2 (straight lines). A shorter lag phase and an about 5-fold higher subsequent H2O2-dependent steady-state ABTS radical formation rate (Fig. 2B; 26.7 ± 1.6 m− s−1) were observed as compared with the lipid-free samples. Thus, TOCL promotes the H2O2-mediated cyt c–based peroxidase activity, which also translates to an about 2.6-fold higher relative product yield (Fig. 2A; 53 μm ABTS radicals).

Upon application of tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin (TLCL)-containing liposomes (red), cyt c–based peroxidase activity was observed even in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 2A, dashed line), yielding about 20 μm ABTS radicals after 1 h. Moreover, the three kinetic phases described above were clearly visible. In the additional presence of H2O2 (Fig. 2A, straight line) a shorter lag phase, an unchanged subsequent steady-state ABTS radical formation rate, and a quicker cease of peroxidase activity were observed, yielding similar overall product yields (22 μm after 40 min). As TLCL does not influence the H2O2 concentration–dependent cyt c–based peroxidase activity (Fig. S1), a comparable rate was determined (Fig. 2B; 4.3 ± 0.6 m−1 s−1) as compared with the lipid-free measurements. Thus, TLCL is able to replace H2O2 in terms of activation and promotion of cyt c–based peroxidase activity but shows no cumulative effects in the additional presence of H2O2.

Control measurements with 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PLPC)-containing liposomes (green) showed no effect of this lipid on the cyt c–based peroxidase activity either in the absence or presence of H2O2. This holds for the kinetics of ABTS radical formation (Fig. 2A) as well as for the calculated H2O2-dependent steady-state peroxidase activity of cyt c (Fig. 2B; 6.0 ± 1.0 m−1 s−1). Thus, the reported effects of TOCL and TLCL on cyt c–based peroxidase activity are cardiolipin-specific.

Control measurements were also performed at continuous H2O2 production by applying the glucose oxidase (GO)–glucose system. Again, the ABTS-based measurements showed sigmoidal kinetics (Fig. S2). Both in the absence of lipid (black) and in the presence of TOCL-containing liposomes (blue), higher constant H2O2 production rates translated to shorter lag phases, higher steady-state enzyme activities, and a quicker cease of cyt c–based peroxidase activity. TOCL strongly promoted those effects. Accordingly, in the presence of the lipid, about 3.5-fold higher relative enzymatic efficiencies of cyt c were observed as calculated from the amount of ABTS radicals formed after 180 min. However, both in the absence and in the presence of TOCL-containing liposomes, the relative product yield again decreased at higher H2O2 production rates.

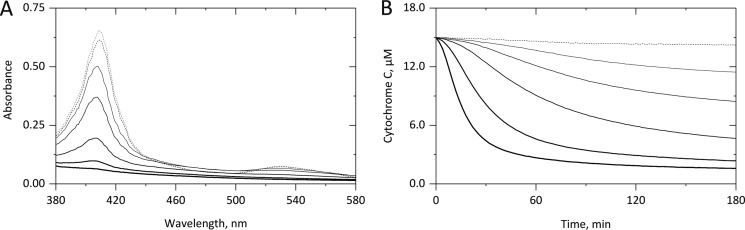

H2O2- and cardiolipin-derived degradation of cytochrome c

To further prove the connection between cyt c–based peroxidase activity and its subsequent inactivation, we monitored spectral changes of cyt c upon its incubation with H2O2 and/or cardiolipin. The cyt c spectrum (Fig. 3A) clearly showed that in the absence of H2O2 (dashed lines) almost no Soret band loss was observed within 3 h of incubation (gray to black), indicating no substantial heme destruction. However, increasing amounts of H2O2 (bolder straight lines) led to a concentration-dependent decrease both of the Soret band at 409 nm and the lower α and β bands beyond 510 nm, indicating heme bleaching. By continuously monitoring the Soret band loss at 409 nm (Fig. 3B), H2O2 concentration–dependent sigmoidal curves correlated with the time-dependent peroxidase activity of cyt c (Fig. 1A). In the absence of H2O2 (dashed line), no significant Soret band loss was observed.

Figure 3.

H2O2-derived degradation of cytochrome c. 15 μm cyt c was incubated in 10 mm PB, pH 7.4, either in the absence (dashed) or presence of H2O2 (straight lines; 75, 150, 300, 750, and 1500 μm) for 3 h at 37 °C. As shown in A, although in the absence of H2O2 an incubation time of 3 h did not result in significant spectral changes (compare gray and black dashed lines), incubation with H2O2 for 3 h led to a concentration-dependent decrease in the Soret band and the heme-derived bands beyond 510 nm. As shown in B, by continuously monitoring the loss of the Soret band an H2O2-concentration-dependent loss of the Soret band was observed, indicating a progressive loss of heme-containing cyt c. Averaged curves from three independent experiments are given.

By replotting the kobs values determined from the linear part of the time-dependent Soret band loss versus the H2O2 concentrations used, a linear correlation was observed (Fig. 4B, black) and translated to a k2 value of 0.53 ± 0.01 m−1 s−1 for the H2O2-derived heme destruction in cyt c (Fig. 4C). Control measurements showed a correlation of the H2O2-derived Soret band loss (Fig. S3, squares) with the release of free iron (Fig. S3, circles), thus providing additional proof for the H2O2-derived heme destruction as a cause for the autocatalytic inactivation of cyt c–based peroxidase activity. Thereby, the free iron concentration was determined by repeated sampling and application of the ferrozine assay. The corresponding calibration curve is given as Fig. S4.

Figure 4.

Effect of cardiolipin on the degradation of cytochrome c. 15 μm cyt c was incubated in the absence or presence of 1.5 mm liposomes with up to 500 μm H2O2 in 10 mm PB, pH 7.4, at 37 °C for up to 3 h. As shown in A, both in the absence of lipid (black) and in the presence of PLPC (green) in the absence of H2O2 (dashed) no heme degradation occurs, whereas in the presence of H2O2 (75 μm; straight) a small heme loss takes place. With TOCL (blue) in the presence of H2O2 comparable heme degradation is observed with a faster kinetics. After preincubation with TLCL (red) even in the absence of H2O2 a quick and more substantial heme degradation takes place that, in the additional presence of H2O2, leads to a complete heme loss. In B, the kobs value obtained from the linear phase of the Soret band decrease is replotted against the H2O2 concentration and always exhibits a linear relationship. As shown in C, from the corresponding slopes, k2 values for the H2O2-derived heme degradation were calculated, showing considerably higher values in the presence of CL-containing liposomes. In A, averaged kinetic curves from three independent measurements are shown; in B and C, the corresponding mean (columns) and S.D. (error bars) values are shown.

Comparable measurements with TOCL-containing liposomes (Fig. 4A, blue) also showed no Soret band loss in the absence of H2O2 (dashed line). However, in its presence (straight line), considerably faster but only partial heme degradation was observed. Again, a linear correlation between the kobs values (linear part of the kinetics) and the H2O2 concentration was determined (Fig. 4B), yielding a k2 value of 1.58 ± 0.03 m−1 s−1 (Fig. 4C). Thus, the promoting effect of TOCL on H2O2-mediated cyt c–based peroxidase activity (Fig. 2) translates to an about 3 times faster heme degradation. PLPC (green) did not influence the H2O2-derived heme degradation (Fig. 4, A–C) as the lipid has no effect on cyt c–based peroxidase activity (Fig. 2, A and B).

The results in the presence of TLCL-containing liposomes (red) were also comparable with the data from the peroxidase activity measurements. Even in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 4A, dashed line), a short lag phase was followed by an exponential loss of the Soret band intensity, indicating heme destruction in about 77% of the cyt c proteins. In the additional presence of H2O2 (straight line), an instant, even faster, and almost complete loss of the Soret band was observed, corresponding to the quick deactivation of the cyt c–based peroxidase activity observed under these conditions (Fig. 2). From the replot of the linear part of the Soret band loss against the H2O2 concentration, a k2 value of 2.48 ± 0.21 m−1 s−1 was calculated, indicating an almost 5 times faster H2O2-derived heme degradation in the presence of TLCL. Thereby, the linear relationship is shifted to higher kobs values, illustrating the heme-degrading effect of this lipid in the absence of H2O2.

Effect of cardiolipin-derived lipid hydroperoxides

The results clearly show that TOCL promotes both cyt c–based peroxidase activity (Fig. 2) and subsequent heme degradation (Fig. 4) only in the presence of H2O2, whereas TLCL promotes the named processes even in the absence of H2O2. This difference may result from the activation of cyt c–based peroxidase activity by pre-existing LOOHs present in TLCL preparations. It is important to note that TLCL used in the study was derived from a bovine heart preparation and thus contained some amount of endogenously or artificially produced LOOH species (Fig. S5). TLCL-derived lipid peroxides can lead to the formation of further LOOHs and thus support both peroxidase activity and subsequent heme loss of cyt c in an autocatalytic fashion. To prove this hypothesis, TLCL was preincubated with triphenylphosphine (PPh3) to reduce the LOOH amount before preparing liposomes, performing peroxidase activity measurements, and studying heme degradation.

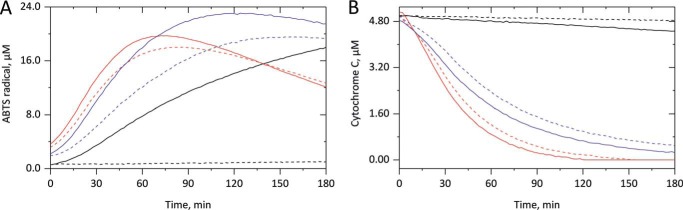

Upon preincubation of TLCL (300 μm lipid concentration) with PPh3, the amount of LOOH was significantly reduced from 2.22 ± 0.24 to 0.73 ± 0.11 μm (Fig. S6). As was shown already above, nonreduced TLCL (Fig. 5A, red) strongly promoted cyt c–based peroxidase on its own (dashed line) and even more so in the presence of H2O2 (straight line) as compared with the lipid-free control (black). In contrast, application of reduced TLCL (violet) with or without H2O2 supplementation resulted in lower peroxidase activity. Furthermore, higher ABTS radical yields were obtained as compared with nonreduced TLCL, indicating lower levels of heme degradation upon application of the lipid with a reduced LOOH content. These results prove a substantial contribution of LOOH to the self-limiting cyt c–based peroxidase activity.

Figure 5.

Role of cardiolipin-derived lipid hydroperoxide reduction on cyt c peroxidase activity and enzyme degradation. In A, peroxidase activity measurements were performed in the absence (black) of lipid or in the presence of liposomes (500 μm lipid concentration) containing nonreduced (red) or reduced (violet) TLCL by incubating 5 μm cyt c without (dashed) or with (straight) 25 μm H2O2 for 180 min in 10 mm PB at 37 °C. ABTS radical formation from 1 mm ABTS was monitored at 734 nm. The strong peroxidase activity–promoting effects of TLCL both in the absence and presence of H2O2 are considerably inhibited by previous reduction of the LOOH amount. As shown in B, the H2O2-independent TLCL-derived heme degradation in cyt c is also considerably disturbed by reducing the LOOH amount. Averaged kinetic curves from three independent experiments are displayed.

By monitoring the Soret band loss for nonreduced TLCL (Fig. 5B, red), a complete heme loss was observed within the 3-h measuring time, both in the absence (dashed) and in the presence (straight) of hydrogen peroxide. Upon application of reduced TLCL (violet), heme degradation was partially inhibited, indicating a role of lipid hydroperoxides in peroxidase-derived heme destruction in cyt c. However, still an almost complete heme loss was obtained at the end of the experiment. Most likely the peroxidase activity–mediated autocatalytic reformation of lipid hydroperoxides in the presence of molecular oxygen keeps the named enzymatic activity running, which, in turn, causes heme degradation and iron release. Indeed, measuring cyt c Soret band loss in the presence of TLCL under hypoxic conditions, a significantly lower rate of heme degradation was observed (Fig. S7), indicating the involvement of oxygen-mediated reactions.

H2O2- and cardiolipin-derived modification of cytochrome c

Previous results clearly demonstrated inactivation of cyt c during the peroxidase cycle in the presence of H2O2 alone or in combination with cardiolipin. Importantly, TLCL even in the absence of H2O2 was capable not only to activate cyt c peroxidase activity but also to induce its inactivation accompanied by heme destruction and subsequent iron release. Cyt c inactivation was proposed to be derived from oxidative degradation of the protein by reactive products released during the peroxidase cycle. To map oxidative post-translational modifications (oxPTMs) of cyt c (100 μm) incubated alone or in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (1 mm) and/or TLCL (10 mm), we used a gel-based bottom-up proteomics approach to monitor over 50 modifications on 10 amino acid residues (Table S2). It is important to note that LC-MS/MS–based identification of the modification sites performed in this study provided only qualitative results and did not include any quantitative values.

Direct oxidation of Met, Trp, Pro, His, Phe, and Tyr amino acid residues was detected in all studied conditions (Table 1 and Table S3). Both Met residues of cyt c (Met-65 and -80) were detected in the form of methionine sulfoxide. Interestingly, despite the high frequency of peptides carrying Met sulfoxides (especially for Met-65), further oxidation of Met residues to sulfones was not detected. Alternatively, both Cys residues (Cys-14 and -17) were found to be heavily oxidized to sulfonic acid but only in the samples incubated with H2O2 (60 min), TLCL (30 and 60 min), and a combination of both (30 and 60 min). No intermediate oxidation states of Cys residues (sulfenic or sulfinic acids) were identified. The single Trp residue in position 59 was oxidized to hydroxy-Trp/oxindolylalanine (mass increment of 16 atomic mass units relative to unmodified Trp) and dihydroxy-Trp/N-formylkynurenine (32 atomic mass units) in all samples, and no further Trp oxPTMs were detected. Of four Tyr residues, three (Tyr-48, -67, and -97) were modified to dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA; Tyr-48, -67, and -97), DOPA quinone (DQ; Tyr-48 and -67), and trihydroxyphenylalanine (TOPA; Tyr-97). Tyr-74, however, was not detected in any of those three oxidation states. Single oxidation (+16 atomic mass units) was confirmed for His-33 and Phe-37, -46, and -82 in most of the samples as well. Pro-30, -44, -71, and -76 were found with mass increments of 14 atomic mass units (pyroglutamic acid; positions 30, 44, and 76) and 16 atomic mass units (Pro-30, -44, -71, and -76). A mass increment of 16 atomic mass units on a proline residue can correspond either to hydroxylation or carbonylation to glutamic semialdehyde. Protein carbonylation, a well-known oxPTM formed usually via metal-catalyzed oxidation of Pro, Thr, Arg, and Lys residues, was reported previously for H2O2-treated cyt c (25). However, exact confirmation of carbonylated residues using tandem MS has not been provided so far to the best of our knowledge.

Table 1.

Summary of cyt c modifications identified by gel-based bottom-up LC-MS/MS experiments in the absence, or presence of H2O2, TLCL or combination of both

Cyt c (100 μm) was incubated in ammonium bicarbonate buffer alone, in the presence of H2O2 (1mm), TLCL (10 mm) or combination of both for 30- and 60-min. Proteins were separate by SDS-PAGE, digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. PTMs were identified from obtained tandem mass spectra using search engine–assisted database search.

Here, we demonstrated oxidative carbonylation on at least 14 cyt c amino acid residues. Among carbonylated amino acid residue, the highest number of modified positions was assigned to Lys. Of 18 Lys residues, seven (Lys-39, -53, -55, -72, -73, -79, and -99) were oxidized to aminoadipic semialdehyde. Seven of eight available Thr residues were oxidized to 2-amino-3-ketobutyric acid (Thr-19, -28, -40, -49, -58, -63, and -78 but not Thr-102). As mentioned before, for Pro residues, both hydroxylation and carbonylation to glutamic semialdehyde result in the same mass increment of 16 atomic mass units and thus are indistinguishable without carbonyl-specific derivatization. Overall, oxidation of Pro with a mass increment of 16 atomic mass units was detected for all four available Pro residues, including Pro-71 (only in TLCL-treated samples). Interestingly, neither of the two Arg residues (positions 38 and 91) have been shown to be carbonylated to glutamic semialdehyde.

Autogenerated trihydroxyphenylalanine quinone (TPQ)-mediated Lys carbonylation

Tyr residues in cyt c are believed to play an important role not only in cyt c peroxidase catalytic activity but also in peroxidase cycle–induced enzyme inactivation. The proposed formation of Tyr radicals and the presence of di-Tyr cross-links in H2O2-treated cyt c were confirmed in several studies using specific di-Tyr fluorescence (7, 23, 26). Based on the mapping of oxidative modifications described above, it was rather surprising that Tyr-74 was not detected in either of the three considered oxidative states (DOPA, DQ, and TOPA). Thus, the possibility of di-Tyr cross-link formation was further evaluated.

Cross-linked peptides are particularly challenging for identification using bottom-up proteomics profiling. Indeed, almost no MS/MS-based identifications of sites of di-Tyr formation are available. Recently, we developed a new MS-based approach to localize cross-linked Tyr residues in in vitro oxidized human serum albumin using mass increments of in silico predicted Tyr-containing tryptic peptides as variable modifications to be used in the search engine–based identification of di-Tyr–linked sequences (27). This strategy was proven to be successful for cyt c samples as well. Indeed, cross-linked peptides representing di-Tyr formation between Tyr-67 and Tyr-74 were identified in all experimental conditions, whereas peptides cross-linked via Tyr-48 (homodimer) and Tyr-48 and Tyr-74 were present only in the samples incubated with TLCL. These results demonstrated significant involvement of the residue at position 74 in Tyr radical–mediated protein cross-linking. That both Tyr modifications and extensive Lys carbonylation were present even in untreated cyt c samples was rather surprising and suggested a possibility of mechanistic correlation between those two modification types in cyt c.

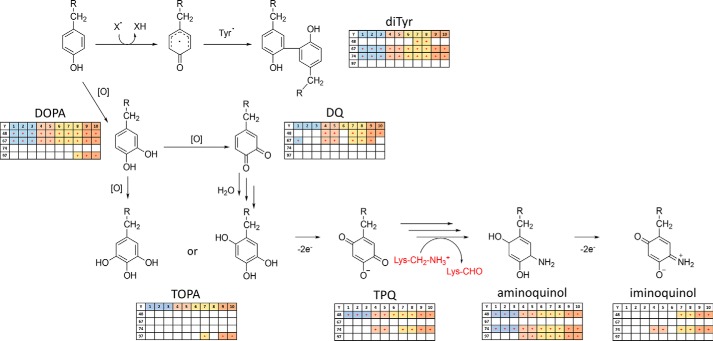

Taking into account the presence of several oxidation states for cyt c Tyr residues accompanied by a high number of carbonylated Lys residues, we speculated that Lys deamination to carbonyl-containing aminoadipic semialdehyde via in situ produced TPQ “cofactor,” similar to the enzymatic deamination of primary amines described for copper amine oxidase (28), might occur in cyt c under oxidative environment accompanied by the release of a free iron (Fig. S8). To confirm this hypothesis, mass increments corresponding to Tyr oxidation products leading to TPQ formation as well as their amino derivatives were calculated and used as variable modifications for the database search in our experiments. Those included already-described Tyr oxPTMs such as di-Tyr cross-links, DOPA, TOPA, and DQ as well as new modifications, including TPQ, aminoquinol, and iminoquinol. Indeed, analysis of proteomics data resulted in identification of all proposed Tyr PTMs in cyt c samples (Fig. 6). Of course, MS-based experiments do not provide full structural assignment of modified residues. However, considering the specific elemental composition of modified residues (e.g. C9H14N2O4 for aminoquinol as a residue) and derived mass increments relative to Tyr residue (e.g. 33.0215 atomic mass units) in combination with the high resolution and mass accuracy of the Orbitrap mass analyzer, our data provide strong support for the proposed structures.

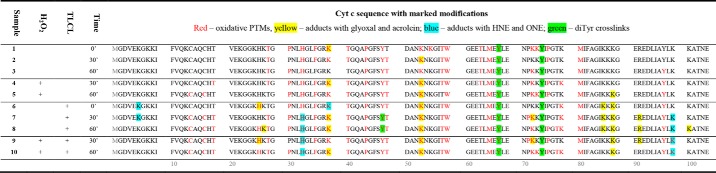

Figure 6.

Proposed pathway of Tyr residue oxidation in cyt c protein leading to the autogeneration of TPQ followed by Lys residue deamination to aminoadipic semialdehyde. Insets demonstrate results of MS/MS-based identification of corresponding modifications on Tyr-48, -67, -74, and -97 residues of cyt c in the absence (columns 1–3, blue), or presence of H2O2 (columns 4 and 5, red), TLCL (columns 6–8, yellow) or combination of both (columns 9 and 10, orange). diTyr, dityrosine cross-links.

Thus, considering previously described (see “H2O2- and cardiolipin-derived modification of cytochrome c”) and newly considered PTMs, we confirmed modification of Tyr-48 to di-Tyr (homo- and heterodimer with Tyr-74, both in TLCL-containing samples), DOPA (all incubations), DQ (H2O2, TLCL, and combination of both), TPQ (all conditions), aminoquinol (all conditions), and iminoquinol (TLCL with and without H2O2) (Fig. 6) Examples of tandem mass spectra of TPQ-, aminoquinol-, and iminoquinol-modified Tyr-48–containing peptides are shown in Fig. S9. Furthermore, relative label-free quantification of Tyr-48–containing peptides demonstrated their presence mostly in H2O2- and TLCL-treated samples (Fig. S10).

In contrast, Tyr-67 was detected only in the form of di-Tyr (heterodimer with Tyr-74; all conditions), DOPA (all conditions), and DQ (control, H2O2, and TLCL + H2O2 samples). Tyr-74 was identified in the form of di-Tyr cross-links (heterodimers with Tyr-67 in all conditions and with Tyr-48 for TLCL samples), TPQ (H2O2, TLCL, and combination of both), aminoquinol (all conditions), and iminoquinol (H2O2, TLCL, and combination of both). Finally, Tyr-97 was detected in modified form only in H2O2- and TLCL-containing samples, including DOPA (TLCL+ H2O2), TOPA (only TLCL and TLCL+ H2O2), and aminoquinol (H2O2, TLCL, and combination of both). Overall, each Tyr residue showed certain specificity in terms of oxPTMs as well as sample treatment types with a general tendency for TPQ and iminoquinol to be present in H2O2-containing samples, independent of the presence of TLCL, with Tyr-48 and -74 showing the highest coverage of oxPTM along the whole proposed pathway (Fig. 6).

Cytochrome c modifications by electrophilic lipid peroxidation products

Finally, we investigated cyt c adducts between nucleophilic amino acid residues (Lys, Arg, His, and Cys) and electrophilic lipid peroxidation products, including low-molecular-weight aldehydes such as acrolein, glyoxal, and methylglyoxal as well as well-known α,β-unsaturated aldehydes, hydroxynonenals (HNEs), and oxononenals (ONEs) formed by a β-scission of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid at the C9 position. As expected, HNE and ONE Michael adducts were identified only in the samples coincubated with TLCL. In total, four modification sites were identified, including Lys-5 (ONE), His-33 (ONE and HNE), Lys-39 (ONE), and Lys-99 (ONE).

Adducts with glyoxal and acrolein were confirmed for His-26, Lys-27, His-33, Lys-39, Lys-53, Lys-72, Lys-86, Lys-88, Arg-91, and Lys-100. The majority of the modifications were identified in TLCL-treated samples; however, carboxymethyl-Lys was identified at positions 39, 53, and 88 even in the sample not exposed to TLCL during the experiments. Taking into account that cyt c used in the study was derived from a bovine heart preparation, these modifications might be either present in the original sample or derived from copurified lipids after oxidant exposure.

Comparison of cytochrome c modifications in the presence of H2O2 and/or TLCL

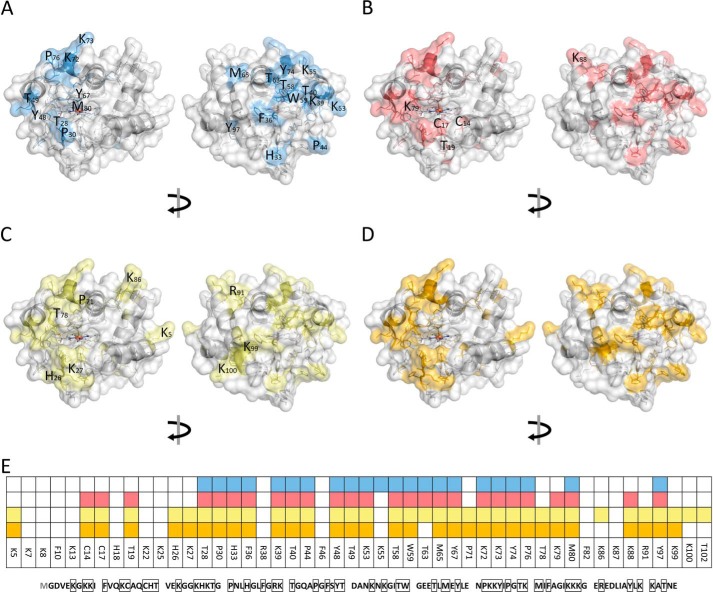

Comparing oxidation sites between different samples, it can be seen that most of the oxPTMs were detectable already in untreated samples (control 0-, 30-, and 60-min incubation) (Fig. 7A). Once more, it is important to note that LC-MS/MS–based identification of modification sites performed in this study provided only qualitative results and did not include any quantitative values.

Figure 7.

Modification of cytochrome c identified by LC-MS/MS in control (A), H2O2 (B), TLCL (C), and H2O2 and TLCL (D) incubations and a summary of all (E). Cyt c (100 μm) was incubated in ammonium bicarbonate buffer alone or in the presence of H2O2 (1 mm), TLCL (10 mm), or a combination of both for 30 and 60 min. Proteins were separate by SDS-PAGE, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. PTMs were identified from obtained tandem mass spectra using a search engine–assisted database search. Tertiary structure elements of the protein are shown in cartoon representation, and the surface is shown as semitransparent. Amino acid residues representing possible PTM sites are shown as sticks whereby the residues on which modifications were detected are shown in blue (autoxidation), red (oxidation after incubation with H2O2), green (TLCL), and orange (H2O2 and TLCL). For B, C, and D, only new modifications sites not present in untreated samples are marked with the amino acid one-letter code and position. A model based on Protein Data Bank code 2b4z (cyt c from bovine heart; 1.5-Å resolution) was used and modified with PyMOL version 0.99.

Interestingly, residues in the middle of the cyt c sequence (Fig. 7B) were oxidized in most of the samples independently of the treatment conditions (Thr-28, Pro-30, His-33, Phe-36, Lys-39, Thr-40, Pro-44, Tyr-48, Thr-49, Lys-53, Thr-58, Trp-59, Met-65, Tyr-67, Pro-76, and Met-80). Oxidation of Cys-14 and -17 to sulfonic acid occurred only in the samples treated with H2O2, TLCL, and a combination of both, indicating significant conformational changes in the cyt c heme-coordinating pocket in conditions promoting peroxidase activity and protein inactivation (Fig. 7, A–D). Additionally, specific oxidation induced in the presence of H2O2 and TLCL included carbonylation of Thr-19 and Lys-79 as well as a carboxymethyl adduct on Lys-88. Furthermore, several site-specific oxidative PTMs were detected only in the samples treated with TLCL alone or in the presence of H2O2 (His-26; cross-links between Tyr-48 and Tyr-48 and Tyr-48 and Tyr-74; Pro-71; and Lys-99; Fig. 7, C and D). Interestingly, the presence of H2O2 in TLCL-treated samples did not result in any additional modification, indicating the absence of a cumulative effect between lipid and hydrogen peroxide exposure.

Cyt c carbonylation reduced its ability to bind CL

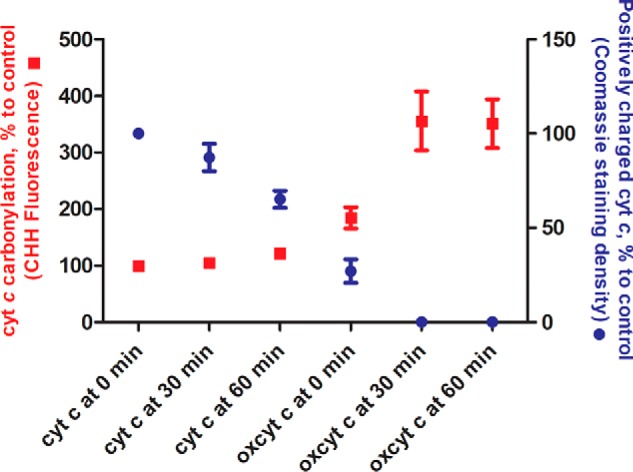

To demonstrate that cyt c carbonylation attenuates its binding to CL, the extent of cyt c carbonylation upon H2O2 treatment was relatively quantified using cyt c labeling with a carbonyl-reactive fluorescent dye, 7-(diethylamino)-coumarin-3-carbohydrazide (CHH) (see Fig. 9 and Fig. S11A). Cyt c incubation with hydrogen peroxide for 30 and 60 min resulted in more than a 3-fold increase of total protein carbonyls. Using reverse-mode native PAGE, we demonstrated significant reduction in cyt c positive net charge upon oxidation, proportional to the increase of cyt c carbonylation signal (Fig. 9 and Fig. S11B).

Figure 9.

Cyt c carbonylation and associated loss of positive charge upon oxidation with hydrogen peroxide. Cyt c (100 μm) was incubated in the absence or presence of H2O2 (1 mm) for 0, 30, and 60 min. Protein carbonylation (left axis, red) was quantified relative to control (cyt c incubated in the absence of hydrogen peroxide for 0 min) using derivatization with the carbonyl-specific fluorescence dye CHH and SDS-PAGE separation. Reduction of cyt c positive charge (right axis, blue) was quantified relative to control (cyt c incubated in the absence of hydrogen peroxide for 0 min) using native PAGE performed in reverse electrophoresis mode. Data are expressed as mean (points) ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3).

Furthermore, using a competitive binding assay utilizing nonyl acridine orange (NAO), we determined the decrease in binding of CL and cyt c upon oxidation (Table 2). Thus, the CL–cyt c binding constant (Kb) for control protein sample as well as cyt c incubated for 30 and 60 min in the absence of H2O2 was estimated as 15 × 107 m−1. Incubation with hydrogen peroxide for 30 and 60 min led to a significant decrease of Kb values (3-fold), providing a clear correlation among cyt c carbonylation, associated decrease of protein positive charge, and its ability to bind to CL.

Table 2.

Binding constants for cyt c incubated in the absence and presence of H2O2 with TLCL-containing liposomes

POPC (negative control) and POPC/TLCL liposomes (1 mm total lipid) were incubated with cyt c (20 μm) in the absence or presence of H2O2 (1 mm) for 0, 30, and 60 min); NAO was added after 30 min for another 1 h. Samples were separated by native PAGE in reverse mode, and fluorescence of unbound NAO was measured using signal from POPC liposome (no binding) as a negative control.

| H2O2 | Time |

K binding constant (Kb) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLCL liposomesa | p valueb | |||

| min | × 107m−1 | |||

| Unoxidized cyt c | − | 0 | 15.4 ± 1.08 | |

| Unoxidized cyt c | − | 30 | 14.8 ± 2.46 | ns (0.8864) |

| Unoxidized cyt c | − | 60 | 15.0 ± 0.70 | ns (0.8281) |

| Oxidized cyt c | + | 0 | 13.1 ± 1.54 | ns (0.3728) |

| Oxidized cyt c | + | 30 | 5.02 ± 1.98 | * (0.0199) |

| Oxidized cyt c | + | 60 | 4.29 ± 2.55 | * (0.0309) |

a Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

b Comparisons between the control group (unoxidized cyt c at 0 min) and each other group were performed using the t test. *, significant differences with p < 0.05 versus control group; ns, not significant.

Discussion

Recently, cyt c has received a lot of scientific attention due its role in apoptosis associated with cyt c release in cytoplasm and caspase activation. Cyt c forms a complex with the mitochondrion-specific lipid cardiolipin, which, upon oxidation, leads to the detachment of the protein from the inner mitochondrial membrane, permeabilization of the outer membrane, and subsequent release of cyt c to the cytoplasm (29). During this pathway, cyt c gains a peroxidase function, utilizing H2O2 and lipid-derived peroxides as substrates. However, the exact mechanism of transition of cyt c from low- to high-peroxidase state remains elusive. To address, at least partially, this question, we used a combination of biochemical methods with bottom-up proteomics for identification of cyt c oxPTMs. Recently, a role of H2O2-mediated oxPTMs in the promotion of the five-coordinated heme state of cyt c during precatalytic lag phase was proposed (30). Indeed, higher H2O2 concentrations resulted in a shorter lag phase, consistent with the idea of faster oxidation rates of cyt c in the presence of high oxidant concentrations. TOCL promoted cyt c peroxidase activity, leading to the shorter lag phase and faster enzyme inactivation. Electrostatic interactions between positively charged residues of cyt c and negatively charged phosphate groups of CL are essential to cyt c–CL complex formation and believed to be a primary driving force in respect to hydrophobic interaction and hydrogen bonding. Recently, it was demonstrated that several sites on cyt c are engaged in CL–cyt c interactions governed by electrostatic forces (31). It was proposed that sites A and L, although located at the opposite end of the protein, can be seen as a joint binding site containing hydrophobic and positively charged residues. Binding via such a noncontiguous site results in opening of the heme pocket via membrane pulling and thus promotes cyt c peroxidase activity.

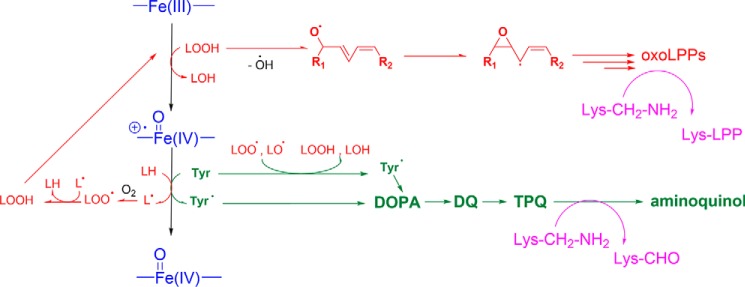

Interestingly, TLCL alone in the absence of H2O2 also resulted in activation of peroxidase activity, which we showed to be dependent on the presence of LOOH in TLCL preparations. Apparently, the combined effect of structural remodeling of cyt c via CL–cyt c complex formation and the presence of initially low levels of organic peroxides was sufficient to initiate the peroxidase cycle. We propose that high levels of TLCL-mediated peroxidase activity, despite a low level of initial LOOH (2.2 μm) as an initial substrate, can be explained by continuous LOOH production from native TLCL via free radicals generated as by-products of the peroxidase cycle (Fig. 8, red route). In situ LOOH production results in a continuous substrate supply, thus fueling the peroxidase cycle, producing new radicals and creating a closed loop responsible for the fast enzyme inactivation. Indeed, upon removal of LOOH, peroxidase activity of cyt c–TLCL closely resembled the TOCL curve. Interestingly, we did not observe a cumulative effect between nonreduced TLCL and H2O2 on reaction kinetics, and TLCL alone was capable to stimulate fast cyt c inactivation and degradation.

Figure 8.

Summary of proposed reaction mechanisms leading to TLCL (red route) and protein (green) oxidative modifications, including Lys deamination to aminoadipic semialdehyde or adduct formation with carbonylated lipid peroxidation products (purple) during cyt c peroxidase cycle (blue). LOOH represents CL-derived lipid peroxide. oxoLPPs, carbonylated lipid peroxidation products.

The majority of the studies on the role of the cyt c–CL complex and its peroxidase activity have been focused on CL oxidative modifications associated with the changes in mitochondrial membrane properties leading to its permeabilization (7), leaving the significance of cyt c oxPTMs for complex formation, peroxidase activity initiation, and cyt c dissociation from membranes often overlooked. Here, to follow up on observed changes in reaction kinetics, we monitored multiple oxPTMs of cyt c in the absence or presence of H2O2, TLCL, and a combination of both.

In all studied conditions, we observed a high number of oxidative modifications covering the middle part of the cyt c sequence. However, heme-region amino acids were not significantly modified unless severe treatment was applied. Tyr residues and their PTMs are usually found to be relevant in peroxidase activity of classical enzymes as well as cyt c peroxidase (25). Roles of Tyr residues in the peroxidase cycle are usually associated with the formation of Tyr radicals via one-electron reduction of Compound I to Compound II. Tyr radical formation is often followed by its recombination to the corresponding dityrosine cross-links (23); however, the exact localization of PTM sites has never been provided. Here, we detected three different types of di-Tyr cross-links in cyt c involving Tyr-48, -67, and -74. The Tyr-67 hydrogen bond network is essential for heme coordination, and tyrosine may also serve as an electron donor upon Compound I to Compound II one-electron reduction (Fig. 8, green route). Furthermore, our results indicate significant involvement of Tyr-74 in this process because only di-Tyr hetero- but not homodimers between Tyr-67 and Tyr-74 were identified. Interestingly, involvement of Tyr-48, another surface-exposed residue, in Tyr radical–mediated di-Tyr cross-links was evident only in TLCL-containing samples. It is interesting to note that cyt c Tyr residues are known to be involved in the regulation of apoptosis via other types of regulatory PTMs, namely phosphorylation and nitration. Thus, Tyr-48 phosphorylation was shown to possess antiapoptotic properties by impairing apoptosis-activating factor 1–mediated activation of caspase-9 (32). Although the direct role of Tyr oxidation in regulation of apoptotic signaling is not fully understood, Tyr-48 present in oxidized form would be unavailable for phosphorylation, thus limiting the antiapoptotic function of this modification via PTM cross-talk.

One of the most abundant oxidative modifications of cyt c was carbonylation. Cyt c carbonylation upon incubation with H2O2 was already demonstrated by OxyBlot (23). Recently, H2O2-induced carbonylation of Lys-72 and -73 during initial lag phase of cyt c peroxidase catalysis was proposed as a mechanism of precatalyst activation (23). Despite detecting carbonylated cyt c proteoforms, the authors, however, did not provide any confirmation of proposed modification sites. Here, we detected 14 carbonylation sites, including seven Lys and seven Thr residues. Such a large number of carbonylation sites made us wonder whether this modification is mechanistically correlated with cyt c peroxidase activity and subsequent radicals formation. Keeping in mind the high involvement of Tyr residues and Tyr-derived PTMs in the peroxidase cycle as well as known reaction mechanisms of Lys carbonylation (33), analogy with the copper-containing enzyme lysyl oxidase, responsible for Lys deamination to aminoadipic semialdehyde in extracellular matrix proteins, first came to mind. However, instead of lysyl oxidase lysine tyrosyl quinone cofactor, we proposed the formation of TPQ, previously described for a copper amine oxidase catalyzing deamination of primary amines (23). Applying these reaction mechanisms to Tyr residues in cyt c, we monitored formation of corresponding TPQ, aminoquinol, and iminoquinol PTMs on both surface-exposed Tyr-48 and -74.

Detection of amino and imino group–containing derivatives of cyt c Tyr residues allows us to propose that autogenerated TPQ “cofactors” in cyt c can mediate Lys deamination to the observed aminoadipic semialdehydes on Lys-39, -53, -55, -72, -73, and -99. Interestingly, of 18 Lys residues, only seven positions were identified in the form of aminoadipic semialdehyde. Furthermore, carbonylated Lys residues are mainly located in site A and contribute to cyt–CL complex formation via electrostatic interactions.

Cyt c is rich in Lys residues, which represent 17% of its sequence versus 6% average Lys abundance in mammalian proteomes. Many Lys residues in cyt c participate in its interaction with lipid membranes and protein-binding partners (30). Our and previously published data indicate high susceptibility of cyt c Lys residues to a variety of modifications, each of which can potentially change the protein net charge and thus interaction surfaces for the binding partners. Indeed, coincubation of cyt c with HNE resulted in a shift of the protein pI from 9.7 to 9.25 (34). Furthermore, using site-directed mutagenesis, it was demonstrated that substitution of Lys-72 and -73 with Asn cancels CL–cyt c binding and CL-induced peroxidase activity, whereas Lys to Arg mutations at the same sites permit cyt c–CL interactions (35). We demonstrated that cyt c carbonylation was associated with the loss of protein positive charge (Fig. 9) and resulted in significantly lower binding constants with CL-containing liposomes, again confirming the importance of Lys residues in establishment of electrostatic interaction between cyt c and cardiolipin. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that similar to the well-studied histone PTM code maintained via methylation of Lys-rich protein tails, cyt c Lys PTMs, formed via autogenerated TPQ-mediated deamination, lead to the elimination of the positive charge and might be seen as a regulatory mechanism responsible for the switch of cyt c interaction partners (e.g. electron transport chain proteins, anionic lipids, or membrane detachment) and thus regulating its moonlighting nature or functional switch.

Experimental procedures

Materials

If not otherwise stated, the chemicals were obtained at the highest available purity from Sigma-Aldrich or Fluka (Honeywell GmbH, Offenbach, Germany) and used without further purification. Cyt c from bovine heart (C3131; 95% purity), GO (G6137; >300 units/mg), horseradish peroxidase (HRP; P6782; >1000 units/mg), NAO, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, and CHH were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The concentration of cyt c was repeatedly checked by performing UV-visible spectroscopy using the Soret band absorption measurement (ϵ408 = 1.04 × 105 m−1 s−1) (36). H2O2 stock solutions were freshly prepared from a 30% stock by diluting in double-distilled H2O, H2O2 concentration was determined spectroscopically at 230 and 240 nm (ϵ240 = 74 m−1 cm−1, ϵ230 = 43.6 m−1 cm−1), and solutions were stored at 4 °C until used (37, 38). Acetonitrile and formic acid were purchased from Biosolve (Valkenswaard, Netherlands). SDS, glycerol, and dithiothreitol (DTT) were obtained from Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany). Trypsin and Coomassie® Brilliant Blue G-250 were purchased from Serva Electrophoresis GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany).

All lipids used in the study were obtained from Avanti® Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL. Briefly, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), PLPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), TLCL (bovine heart), and TOCL were used for liposome preparation. Thereby, if not otherwise stated, the following molar compositions were used: DOPC/PLPC 2:3, DOPC/TOCL 7:3, and DOPC/TLCL/POPE 5:3:2, meaning a cardiolipin concentration of 30 mol % in the corresponding liposomes.

Liposome preparation

LUVs were prepared by extrusion (22, 39). Briefly, single-lipid stock solutions (10 mg/ml in chloroform) were mixed and evaporated in a vacuum centrifuge (Vacuum Concentrator Centrifugal Evaporator R 10.22, Jouan, Fisher Scientific GmbH), and the obtained lipid film was dissolved in phosphate buffer (PB; 10 mm, pH 7.4) (for UV-visible spectroscopy) or ammonium bicarbonate buffer (ABC; 50 mm, pH 7.8) (for gel electrophoresis and MS) by thorough vortexing. The resulting multilamellar vesicles were extruded 19 times through a hydrophilic polycarbonate filter (Merck Millipore, Merck Chemicals GmbH; 25-mm diameter, 0.1-μm pore size) in a mini extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.). LUV size distribution was determined by nanoparticle tracking analysis using a NanoSight LM20 Nanoparticle Analysis System (NanoSight, Amesbury, UK) equipped with a 650 nm laser. For each sample, three measurements (60 s each) at 23.3 °C were performed using a concentration of 107–109 particles/ml. The lipid composition and size of the liposomes applied in the experiments are given in Table S1 where the most common lipid compositions are shown in italics.

Lipid quantification

Lipid concentration in the extruded samples was determined by Bartlett assay (40) with slight modifications (41). Briefly, liposomes were incinerated in HClO4 (70%, v/v; 90 min at 230 °C), ascorbic acid (700 μl; 3%, v/v) and ammonium molybdate solution (700 μl; 3.6 mm in 12.5% perchloric acid, v/v) were added, and samples were incubated for 5 min at 100 °C. The concentration of ammonium phosphomolybdate complexes was determined spectroscopically (Tecan Infinite 200 Pro, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 830 nm by comparison with a calibration curve prepared with 6.4–64 nmol of NaH2PO4.

Lipid hydroperoxide reduction

For selected experiments, LOOHs in the LUVs were reduced by incubating the chloroform stock solution of the lipid mixture (DOPC/TLCL 7:3) with PPh3 (2 mm chloroform) for 1 h at 30 °C in the dark (42). Chloroform was evaporated, and liposomes were prepared as described above. The amount of lipid hydroperoxides before and after PPh3 reduction was determined by monitoring the enzymatic activity of HRP (0.1 μm) in the presence of ABTS (1 mm) in 1 mm liposomes and comparing the obtained values with the ABTS oxidation rates observed in the presence of H2O2.

Peroxidase activity measurements

If not stated otherwise, samples for the peroxidase measurements were prepared in 96-well plates containing cyt c (5 μm), liposomes (500 μm lipid concentration), and ABTS (1 mm) in PB. After preincubation for 5 min at 37 °C, H2O2 (up to 500 μm) was added using the injector device of the plate reader (Tecan Infinite 200 Pro, Männedorf, Switzerland), and the formation of ABTS+• was followed by absorbance measurement at 734 nm (ϵ734 = 1.5 × 104 m−1 s−1) (43) at 37 °C for up to 3 h. From the linear range of absorbance increase curves, the initial ABTS oxidation rate was determined (5).

Selected experiments were also performed in the presence of GO and glucose as a continuous H2O2-producing system (21, 44). Briefly, samples were prepared as described above in the additional presence of GO (up to 4.70 milliunits) and preincubated for 5 min at 37 °C. Glucose (1 mm) was added using the injector device of the plate reader. H2O2 production rates were adjusted by applying different amounts of GO (0.24–4.70 milliunits). A calibration curve obtained from control measurements with HRP (0.1 μm), ABTS (1 mm), glucose (1 mm), and different GO concentrations was consulted.

Heme degradation measurements

Cyt c (5–30 μm) was incubated with an up to 100-fold excess of H2O2 either in the absence or presence of a 100-fold lipid excess in PB (10 mm, pH 7.4). Spectral changes between 380 and 580 nm were followed at 37 °C for 3 h. From the absorbance loss at 408 nm (Soret peak) (21, 36), kobs values were calculated by plotting the linear part of the Soret band loss kinetics against the applied H2O2 concentration. From the slope of these plots, k2 values were calculated by considering the applied cyt c concentration.

Selected experiments were also performed to correlate (21) the Soret band loss with the release of iron from cyt c by applying the ferrozine assay (21, 45) with slight modifications (46, 47). Briefly, cyt c (30 μm) was preincubated in PB (10 mm, pH 7.4) at 37 °C. H2O2 (3 mm) was added by using the injector device of the plate reader. The Soret band loss was followed at 408 nm for up to 3 h. Ascorbic acid (150 mm) was added to selected wells at fixed time points via the injector device of the reader to stop the reaction and reduce iron to the ferrous state. After completion of the absorbance measurements, parts of the samples were transferred either to a well containing ferrozine (2.5 mm; monosodium salt hydrate of 3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-diphenyl-1,2,4-triazine-p,p′-disulfonic acid in 8% ammonium acetate solution) or to a well containing PB. The absorbance was measured at 562 nm (46) using the second well for zero compensation. The free iron concentration in the samples was determined by comparing the obtained net absorbance with a calibration curve generated with ferrozine and FeCl3 under the same experimental conditions.

To monitor cyt c heme degradation at normoxic and hypoxic conditions, TLCL liposomes (1.5 mm in 10 mm PB) were prepared as stated above and incubated with cyt c (15 μm) in PB in a Hellma Precision cell Suprasil® cuvette. For normoxic conditions, the decrease of the Soret band (408 nm) absorbance was monitored over 90 min at 37 °C. For hypoxic measurements, PB was sonicated (10 min at room temperature), and PB and cyt c stock solutions were degassed by vacuum application in an Eppendorf concentrator (10 min at room temperature) and purged with nitrogen (10 min at room temperature) before measurements of Soret band absorbance carried out in a nitrogen-flushed air-tight screw cap Hellma Precision cell Suprasil cuvette.

SDS-PAGE and in-gel digestion

Cyt c (100 μm) was incubated in the absence or presence of TLCL-containing liposomes (10 mm) and H2O2 (1 mm) in ABC at 37 °C for 30 or 60 min. Samples were extracted using a tert-butyl methyl ether (MTBE) protocol (48). Briefly, 350 μl of methanol and 1250 μl of MTBE were added followed by 10 s of vortexing after each step. The mixture was left on a rotating shaker for 1 h at 4 °C. To induce phase separation, 313 μl of deionized water was added. Samples were left on a rotary shaker for an additional 10 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 × g. The upper phase was removed, and the lower aqueous phase together with protein precipitate was dried in the vacuum centrifuge for protein analysis. Dried samples were dissolved in Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mm Tris, 2.5% (w/v) SDS, 0.2% (w/v) bromphenol blue, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% (w/v) glycerol, pH 6.8), separated by SDS-PAGE (18% T, 1 mm), and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. Visible protein lanes were cut out, destained with acetonitrile (50% (v/v) in 50 mm NH4HCO3), centrifuged (1 h at 37 °C at 750 rpm), dehydrated with 100% acetonitrile, and dried by vacuum concentration. Proteins were digested with trypsin (375 ng in 3 mm ABC; 4 h at 37 °C at 550 rpm), and peptides were extracted using consecutive incubations with 100, 50, and 100% acetonitrile (15-min sonication for each step). Combined extracts were vacuum-concentrated and stored at −20 °C. Before MS analysis, peptides were dissolved in 10 μl of 60% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.5% formic acid and further diluted 1:20 with 3% aqueous acetonitrile.

LC-MS/MS of tryptic peptides

A nanoACQUITY UPLC (Waters GmbH) was coupled online to an LTQ Orbitrap XL ETD mass spectrometer equipped with a nano-ESI source (Thermo Fischer Scientific GmbH, Bremen, Germany). Eluent A was aqueous formic acid (0.1%, v/v), and eluent B was formic acid (0.1%, v/v) in acetonitrile. Samples (10 μl) were loaded onto the trap column (nanoACQUITY Symmetry C18; internal diameter, 180 μm; length, 20 mm; particle diameter, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Peptides were separated on a BEH 130 column (C18 phase; internal diameter, 75 μm; length, 100 mm; particle diameter, 1.7 μm) with a flow rate of 0.4 μl/min using two step gradients from 3 to 30% eluent B over 18 min and then to 85% eluent B over 1 min. After an equilibration time of 12 min, samples were injected every 33 min.

The transfer capillary temperature was set to 200 °C, and the tube lens voltage was set to 120 V. An ion spray voltage of 1.5 kV was applied to a PicoTip online nano-ESI emitter (New Objective, Berlin, Germany). The precursor ion survey scans were acquired in the Orbitrap (resolution of 60,000 at m/z 400) for an m/z range from 400 to 2000. Collision-induced dissociation tandem mass spectra (isolation width, 2; activation Q, 0.25; normalized collision energy, 35%; activation time, 30 ms) were recorded in the linear ion trap by data-dependent acquisition for the top six most abundant ions in each survey scan with dynamic exclusion for 60 s using Xcalibur software (version 2.0.7; Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Peptides were identified using Sequest search engine (Proteome Discoverer 1.4, Thermo Scientific) against the UniProt database, allowing up to two missed cleavages and a mass tolerance of 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.8 Da for product ions. The list of variable modifications used for the database search is provided in Table S2. Results were filtered for rank 1 high-confidence peptides and score versus charge states corresponding to Xcorr/z 2.0/2, 2.25/3, 2.5/4, and 2.75/5.

Shotgun MS analysis of lipid hydroperoxides

Dried lipid-containing MTBE extracts were dissolved in ESI solution (methanol/chloroform 2:1 (v/v) containing 5 mm ammonium formate) and analyzed by direct infusion (15 μl) using the robotic nanoflow ion source TriVersa NanoMate (Advion BioSciences, Ithaca, NY) and nanoelectrospray chips (1.4-kV ionization voltage, 0.4 p.s.i. nitrogen backpressure) coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap XL ETD mass spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific) operated in negative ion mode. Transfer capillary temperature was 200 °C, and the tube lens voltage was set to −120 V. Mass spectra were acquired with a target mass resolution of 100,000 at m/z 400 in the Orbitrap mass analyzer. Tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) were acquired in the linear ion trap (LTQ) using an isolation width of 1.5 Da and normalized collision energy of 35%. Data were analyzed manually using the XCalibur software (version 2.0.7).

Cyt c carbonylation analysis using CHH derivatization

Cyt c (100 μm) in phosphate buffer (50 mm, pH 7.0) was incubated with or without H2O2 (1 mm; 37 °C) for 0, 30, and 60 min. Reactions were stopped by ultrafiltration (VivaspinTM 2 ultrafiltration devices with a 5000-molecular-weight-cutoff polyethersulfone filter, Sartorius AG, Hannover, Germany), and protein concentration in recovered solutions was determined by Bradford assay (49). Cyt c (0.4 μm) was incubated with CHH (150 μm; 2 h at 37 °C) and separated by SDS-PAGE (12% T) (50). Gels were washed twice with water (10 min) and visualized on a ChemiDocTM MP (Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH) using Image LabTM software and a DyLight 488 channel filter for blue epi-illumination. Images were quantified using ImageJ (51).

Reduction of cyt c positive charge upon oxidation was studied using native PAGE (7.5% T) separation performed in reverse electrophoresis mode (11). Resulting gels were stained with Coomassie, and images were acquired on a ChemiDoc MP and quantified using ImageJ.

Cyt c–CL binding assay

Large unilamellar liposomes of POPC (5 mm) or POPC/TLC mixture (2.5 mm each) were prepared in phosphate buffer (50 mm, pH 7) containing 100 μm diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid by extrusion as described in under “Liposome preparation.” Liposomes (1 mm total lipid) were incubated with cyt c (20 μm; 30 min at room temperature), afterward NAO (4 mm; 1:4 ratio lipid/NAO) was added, and mixtures were incubated for 1 h (room temperature). 10 μl of each sample was separated by native PAGE (7.5% T) in reverse electrophoresis mode. The fluorescence of NAO was monitored at 520 nm using a ChemiDoc MP. Binding constants were calculated according to Belikova et al. (11).

Author contributions

U. B., M. L., L. M., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. data curation; U. B., M. L., L. M., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. formal analysis; U. B., M. L., L. M., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. investigation; U. B., O. I. S., and M. F. methodology; L. M., J. A., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. conceptualization; L. M. and J. A. resources; L. M., J. A., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. supervision; L. M., J. A., and O. I. S. funding acquisition; L. M., J. A., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. project administration; J. A., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. validation; J. A., O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. writing-review and editing; O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. software; O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. visualization; O. I. S., M. F., and J. F. writing-original draft.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Ralf Hoffmann (Institute of Bioanalytical Chemistry, University of Leipzig) for providing access to the laboratory and mass spectrometers.

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the framework of the e:Med research and funding concept for the SysMedOS project, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grant FE-1236/3-1 (to M. F.), European Regional Development Fund (ERDF; European Union and Free State Saxony) Grants 100146238 and 100121468 (to M. F.), and a Xunta de Galicia postdoctoral scholarship (to L. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S11 and Tables S1–S3.

- cyt c

- cytochrome c

- CL

- cardiolipin

- TOCL

- tetraoleoyl cardiolipin

- TLCL

- tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin

- TPQ

- trihydroxyphenylalanine quinone

- LOOH

- lipid hydroperoxide

- ABTS

- 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid

- LUV

- large unilamellar vesicle

- GO

- glucose oxidase

- PLPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PPh3

- triphenylphosphine

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- oxPTM

- oxidative post-translational modification

- DOPA

- dihydroxyphenylalanine

- DQ

- DOPA quinone

- TOPA

- trihydroxyphenylalanine

- HNE

- hydroxynonenal

- ONE

- oxononenal

- CHH

- 7-(diethylamino)coumarin-3-carbohydrazide

- NAO

- nonyl acridine orange

- Kb

- binding constant

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- DOPC

- 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPE

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- PB

- phosphate buffer

- ABC

- ammonium bicarbonate buffer

- MTBE

- tert-butyl methyl ether

- ETD

- electron-transfer dissociation

- ESI

- electrospray ionization.

References

- 1. Liu X., Kim C. N., Yang J., Jemmerson R., and Wang X. (1996) Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 86, 147–157 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mignotte B., and Vayssiere J. L. (1998) Mitochondria and apoptosis. Eur. J. Biochem. 252, 1–15 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. García-Heredia J. M., Díaz-Moreno I., Nieto P. M., Orzáez M., Kocanis S., Teixeira M., Pérez-Payá E., Díaz-Quintana A., and De la Rosa M. A. (2010) Nitration of tyrosine 74 prevents human cytochrome c to play a key role in apoptosis signaling by blocking caspase-9 activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 981–993 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergstrom C. L., Beales P. A., Lv Y., Vanderlick T. K., and Groves J. T. (2013) Cytochrome c causes pore formation in cardiolipin-containing membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 6269–6274 10.1073/pnas.1303819110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mandal A., Hoop C. L., DeLucia M., Kodali R., Kagan V. E., Ahn J., and van der Wel P. C. (2015) Structural changes and proapoptotic peroxidase activity of cardiolipin-bound mitochondrial cytochrome c. Biophys. J. 109, 1873–1884 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pandiscia L. A., and Schweitzer-Stenner R. (2015) Coexistence of native-like and non-native partially unfolded ferricytochrome c on the surface of cardiolipin-containing liposomes. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 1334–1349 10.1021/jp5104752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kagan V. E., Tyurin V. A., Jiang J., Tyurina Y. Y., Ritov V. B., Amoscato A. A., Osipov A. N., Belikova N. A., Kapralov A. A., Kini V., Vlasova I. I., Zhao Q., Zou M., Di P., Svistunenko D. A., et al. (2005) Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipin oxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 223–232 10.1038/nchembio727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ascenzi P., Coletta M., Wilson M. T., Fiorucci L., Marino M., Polticelli F., Sinibaldi F., and Santucci R. (2015) Cardiolipin-cytochrome c complex: Switching cytochrome c from an electron-transfer shuttle to a myoglobin- and a peroxidase-like heme-protein. IUBMB Life 67, 98–109 10.1002/iub.1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kagan V. E., Bayir H. A., Belikova N. A., Kapralov O., Tyurina Y. Y., Tyurin V. A., Jiang J., Stoyanovsky D. A., Wipf P., Kochanek P. M., Greenberger J. S., Pitt B., Shvedova A. A., and Borisenko G. (2009) Cytochrome c/cardiolipin relations in mitochondria: a kiss of death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 1439–1453 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hüttemann M., Pecina P., Rainbolt M., Sanderson T. H., Kagan V. E., Samavati L., Doan J. W., and Lee I. (2011) The multiple functions of cytochrome c and their regulation in life and death decisions of the mammalian cell: from respiration to apoptosis. Mitochondrion 11, 369–381 10.1016/j.mito.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belikova N. A., Vladimirov Y. A., Osipov A. N., Kapralov A. A., Tyurin V. A., Potapovich M. V., Basova L. V., Peterson J., Kurnikov I. V., and Kagan V. E. (2006) Peroxidase activity and structural transitions of cytochrome c bound to cardiolipin-containing membranes. Biochemistry 45, 4998–5009 10.1021/bi0525573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Basova L. V., Kurnikov I. V., Wang L., Ritov V. B., Belikova N. A., Vlasova I. I., Pacheco A. A., Winnica D. E., Peterson J., Bayir H., Waldeck D. H., and Kagan V. E. (2007) Cardiolipin switch in mitochondria: shutting off the reduction of cytochrome c and turning on the peroxidase activity. Biochemistry 46, 3423–3434 10.1021/bi061854k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patriarca A., Eliseo T., Sinibaldi F., Piro M. C., Melis R., Paci M., Cicero D. O., Polticelli F., Santucci R., and Fiorucci L. (2009) ATP acts as a regulatory effector in modulating structural transitions of cytochrome c: implications for apoptotic activity. Biochemistry 48, 3279–3287 10.1021/bi801837e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giorgio M., Trinei M., Migliaccio E., and Pelicci P. G. (2007) Hydrogen peroxide: a metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 722–728 10.1038/nrm2240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Firsov A. M., Kotova E. A., Korepanova E. A., Osipov A. N., and Antonenko Y. N. (2015) Peroxidative permeabilization of liposomes induced by cytochrome c/cardiolipin complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1848, 767–774 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Firsov A. M., Kotova E. A., Orlov V. N., Antonenko Y. N., and Skulachev V. P. (2016) A mitochondria-targeted antioxidant can inhibit peroxidase activity of cytochrome c by detachment of the protein from liposomes. FEBS Lett. 590, 2836–2843 10.1002/1873-3468.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aluri H. S., Simpson D. C., Allegood J. C., Hu Y., Szczepanek K., Gronert S., Chen Q., and Lesnefsky E. J. (2014) Electron flow into cytochrome c coupled with reactive oxygen species from the electron transport chain converts cytochrome c to a cardiolipin peroxidase: role during ischemia-reperfusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 3199–3207 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Josephs T. M., Morison I. M., Day C. L., Wilbanks S. M., and Ledgerwood E. C. (2014) Enhancing the peroxidase activity of cytochrome c by mutation of residue 41: implications for the peroxidase mechanism and cytochrome c release. Biochem. J. 458, 259–265 10.1042/BJ20131386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Puchkov M. N., Vassarais R. A., Korepanova E. A., and Osipov A. N. (2013) Cytochrome c produces pores in cardiolipin-containing planar bilayer lipid membranes in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828, 208–212 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tyurina Y. Y., Kini V., Tyurin V. A., Vlasova I. I., Jiang J., Kapralov A. A., Belikova N. A., Yalowich J. C., Kurnikov I. V., and Kagan V. E. (2006) Mechanisms of cardiolipin oxidation by cytochrome c: relevance to pro- and antiapoptotic functions of etoposide. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 706–717 10.1124/mol.106.022731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harel S., Salan M. A., and Kanner J. (1988) Iron release from metmyoglobin, methaemoglobin and cytochrome c by a system generating hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 5, 11–19 10.3109/10715768809068554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yurkova I., Huster D., and Arnhold J. (2009) Free radical fragmentation of cardiolipin by cytochrome c. Chem. Phys. Lipids 158, 16–21 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim N. H., Jeong M. S., Choi S. Y., and Kang J. H. (2006) Oxidative modification of cytochrome c by hydrogen peroxide. Mol. Cells 22, 220–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Radi R., Turrens J. F., and Freeman B. A. (1991) Cytochrome c-catalyzed membrane lipid peroxidation by hydrogen peroxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 288, 118–125 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90172-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yin V., Shaw G. S., and Konermann L. (2017) Cytochrome c as a peroxidase: activation of the precatalytic native state by H2O2-induced covalent modifications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15701–15709 10.1021/jacs.7b07106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen Y. R., Chen C. L., Chen W., Zweier J. L., Augusto O., Radi R., and Mason R. P. (2004) Formation of protein tyrosine ortho-semiquinone radical and nitrotyrosine from cytochrome c-derived tyrosyl radical. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18054–18062 10.1074/jbc.M307706200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Annibal A., Colombo G., Milzani A., Dalle-Donne I., Fedorova M., and Hoffmann R. (2016) Identification of dityrosine cross-linked sites in oxidized human serum albumin. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1019, 147–155 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klema V. J., and Wilmot C. M. (2012) The role of protein crystallography in defining the mechanisms of biogenesis and catalysis in copper amine oxidase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 5375–5405 10.3390/ijms13055375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ott M., Robertson J. D., Gogvadze V., Zhivotovsky B., and Orrenius S. (2002) Cytochrome c release from mitochondria proceeds by a two-step process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1259–1263 10.1073/pnas.241655498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alvarez-Paggi D., Hannibal L., Castro M. A., Oviedo-Rouco S., Demicheli V., Tórtora V., Tomasina F., Radi R., and Murgida D. H. (2017) Multifunctional cytochrome c: learning new tricks from an old dog. Chem. Rev. 117, 13382–13460 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohammadyani D., Yanamala N., Samhan-Arias A. K., Kapralov A. A., Stepanov G., Nuar N., Planas-Iglesias J., Sanghera N., Kagan V. E., and Klein-Seetharaman J. (2018) Structural characterization of cardiolipin-driven activation of cytochrome c into a peroxidase and membrane perturbation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1860, 1057–1068 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moreno-Beltrán B., Guerra-Castellano A., Díaz-Quintana A., Del Conte R., García-Mauriño S. M., Díaz-Moreno S., González-Arzola K., Santos-Ocaña C., Velázquez-Campoy A., De la Rosa M. A., Turano P., and Díaz-Moreno I. (2017) Structural basis of mitochondrial dysfunction in response to cytochrome c phosphorylation at tyrosine 48. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E3041–E3050 10.1073/pnas.1618008114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fedorova M. (2017) Diversity of protein carbonylation pathways: direct oxidation, glycoxidation and modifications by lipid peroxidation products, in Protein Carbonylation: Principles, Analysis, and Biological Implications (Ros J., ed) pp. 48–82, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ: 10.1002/9781119374947.ch3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Isom A. L., Barnes S., Wilson L., Kirk M., Coward L., and Darley-Usmar V. (2004) Modification of cytochrome c by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal: evidence for histidine, lysine, and arginine-aldehyde adducts. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 15, 1136–1147 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sinibaldi F., Milazzo L., Howes B. D., Piro M. C., Fiorucci L., Polticelli F., Ascenzi P., Coletta M., Smulevich G., and Santucci R. (2017) The key role played by charge in the interaction of cytochrome c with cardiolipin. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 22, 19–29 10.1007/s00775-016-1404-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Margoliash E., and Frowirt N. (1959) Spectrum of horse-heart cytochrome c. Biochem. J. 71, 570–572 10.1042/bj0710570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beers R. F. Jr., and Sizer I. W. (1952) A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Noble R. W., and Gibson Q. H. (1970) The reaction of ferrous horseradish peroxidase with hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 245, 2409–2413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miyamoto S., Nantes I. L., Faria P. A., Cunha D., Ronsein G. E., Medeiros M. H., and Di Mascio P. (2012) Cytochrome c-promoted cardiolipin oxidation generates singlet molecular oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 11, 1536–1546 10.1039/c2pp25119a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barlett G. R. (1959) Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 234, 466–468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Göse M., Pescador P., and Reibetanz U. (2015) Design of a homogeneous multifunctional supported lipid membrane on layer-by-layer coated microcarriers. Biomacromolecules 16, 757–768 10.1021/bm5016688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakamura T., and Maeda H. (1991) A simple assay for lipid hydroperoxides based on triphenylphosphine oxidation and high-performance liquid chromatography. Lipids 26, 765–768 10.1007/BF02535628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Re R., Pellegrini N., Proteggente A., Pannala A., Yang M., and Rice-Evans C. (1999) Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 26, 1231–1237 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]