Abstract

BACKGROUND

Celiac crisis (CC), a potentially life-threatening condition, is one of the rare clinical presentations of celiac disease (CD). Several cases have been documented in the literature, mostly in children.

AIM

To perform a review of CC cases reported in adult CD patients.

METHODS

A systematic search of the literature was conducted in two databases, PubMed/MEDLINE and EMBASE, using the term “celiac crisis" and its variant "coeliac crisis", from January 1970 onwards. Altogether, 29 articles reporting 42 biopsy-proven cases were found in the search. Here, we summarized the demographic, clinical characteristics, laboratory and diagnostic work-ups, and therapeutic management in these patients.

RESULTS

Among the 42 CD cases, the median age was 50 years (range 23-83), with a 2:1 female to male ratio. The majority of patients (88.1%) developed CC prior to CD diagnosis, while the remaining were previously diagnosed CD cases reporting low adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD). Clinically, patients presented with severe diarrhea (all cases), weight loss (about two thirds) and, in particular situations, with neurologic (6 cases) or cardiovascular (1 case) manifestations or bleeding diathesis (4 cases). One in four patients had a precipitating factor that could have triggered the CC (e.g. trauma, surgery, infections). Laboratory workup of patients revealed a severe malabsorptive state with metabolic acidosis, dehydration, hypoalbuminemia and anemia. The evolution of GFD was favorable in all cases except one, in whom death was reported due to refeeding syndrome.

CONCLUSION

Celiac crisis is a rare but severe and potentially fatal clinical feature of CD. A high index of suspicion is needed to recognize this clinical entity and to deliver proper therapy consisting of supportive care and, subsequently, GFD.

Keywords: Celiac disease, Celiac crisis, Malabsorption, Malnutrition, Diarrhea

Core tip: Celiac disease is well recognized as having a broad spectrum of presentations. Among them, celiac crisis is a rare but potentially life-threatening clinical feature, which has been reported in both pediatric and adult celiac disease cases. Several case reports have been published so far in adults, and our aim was to summarize the current literature in order to better delineate the patients’ profile with respect to possible triggers, clinical characteristics, laboratory workups and management of celiac crisis.

INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease (CD) is a systemic, immune-mediated disease, primarily affecting the small bowel, which occurs in genetically predisposed individuals and is triggered by dietary gluten exposure[1-3]. For many years, CD was considered to be a disease of childhood, being well known as the prototype of malabsorption in the pediatric population. In adults, CD has a different phenotype, frequently presenting with mild digestive signs and symptoms or with extraintestinal features such as anemia, early osteoporosis, chronic fatigue, unexplained infertility or ataxia[2-5].

Celiac crisis (CC) is a rare but potentially life-threatening clinical feature of CD, which has been reported in both children and adults. It was first described in 1953, in a case series of 35 children with a fatality rate of 9%[6-8]. Clinically, CC has a brutal onset with profuse diarrhea, severe dehydration, hemodynamic instability, as well as profound electrolytic and metabolic disturbances, which is considered an acute, fulminant manifestation of CD[9,10]. Acute onset and the rapidly progressing gastrointestinal symptoms of CC, accompanied by compromised metabolic, electrolytic and hemodynamic processes, usually requires hospitalization and intensive care support. Recognition of this condition can be challenging in clinical practice, as infectious causes and not CD are usually thought of in such a clinical scenario. CC diagnosis comprises the acute malabsorptive state, with positive CD serology and histology. An immune stimulus can sometimes be identified as a precipitating factor for CC, such as infections or recent surgery. Treatment consists of intensive nutritional support and a gluten-free diet (GFD).

CC is not very well documented in the literature, with only a handful of case reports and case series published. In fact, currently available guidelines do not yet include this entity in children or adults[2,3,5]. It is, however, classified as a complication of CD in a recent phenotypic classification[11]. Most consider it to be a heraldic manifestation of CD, but it has also been reported as an acute flare of previously untreated CD or in CD patients with dietary transgressions[12].

We herein conducted a review of CC cases reported in adults and tried to summarize the clinical, laboratory and histological characteristics of CC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and article selection

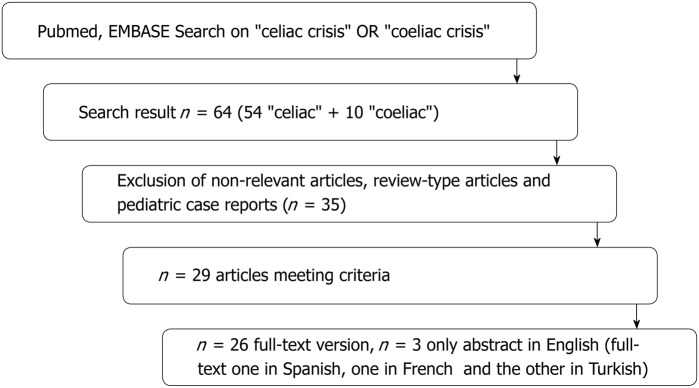

The literature was systematically searched using the term "celiac crisis" (and its variant "coeliac crisis") in two databases, PubMed/MEDLINE and EMBASE. We restricted the search to articles published from January 1970 onwards. The articles identified from this search were checked for access to the article abstract in English, and then the abstract was assessed for relevance to the topic. We included all articles matching these criteria and reporting on adults over 18 years old. We excluded articles referring to pediatric cases (patients under 18 years old). For the remaining articles, we searched for the full-text version and we also checked their references for additional possible articles matching the topic that could have been missed in the initial database search (Figure 1). Full text in English was available for 26/29 articles, while the remaining three were in the Spanish[13], French[14] and Turkish[15] languages, and data regarding clinical, biological, endoscopy and histology were collected after translating the case presentations. All cases included were counted only one time.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the articles considered for the final analysis.

RESULTS

Demographics

Altogether, 42 cases presented in 29 articles were found with the above described search criteria, of which two articles presented 2 cases, another one a case series with 12 cases and the remaining with 1 case each. The demographics and clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Celiac disease published cases – clinical characteristics

| Index | No | Age, yr | Sex | Weight loss | BMI, kg/m2 | Time from the CD diagnosis | Previous GFD/ compliance | Favorable evolution under GFD |

| [26] | 1 | 43 | F | 20 kg/12 mo | 14.7 | 3 yr | Yes, non-compliance | Yes |

| [22] | 1 | 28 | F | - | 14.0 | 21 yr | Yes, non-compliance | - |

| [10] | 1 | 26 | F | - | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [27] | 1 | 24 | F | 4-5 kg/1 wk | 17.5 | 0 | No | Yes |

| [28] | 1 | 69 | M | No | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [25] | 1 | 46 | F | - | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [12] | 1 | 31 | F | 14 kg/1 mo | 17 | 0 | No | Yes |

| [29] | 1 | 43 | M | 35 kg/6 mo | 11 | 0 | No | Yes |

| [30] | 2 | 82, 75 | F, M | -, - | -, - | 0, 0 | No, No | Yes, Yes |

| [31] | 1 | 64 | F | 10 kg | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [32] | 1 | 52 | F | Yes | - | 0 | No | - |

| [33] | 1 | 30 | F | 9 kg/1 mo | 21.5 | 0 | No | Yes |

| [34] | 1 | 83 | M | - | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [35] | 1 | 67 | M | 18 kg/6 mo | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [16] | 12 | mean 58.9 (34-74) | 8F/4M | 12/12 (5-15 kg) | - | 11/12 – 0 | 11/12 – No; 1/12 - Yes, non-compliance | 12/12 – Yes; corticosteroids 6/12 |

| [14] | 1 | 26 | F | - | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [24] | 1 | 50 | F | - | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [36] | 1 | 23 | F | - | 0 | No | Yes | |

| [37] | 1 | 58 | M | 20 kg/2 mo | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [38] | 1 | 49 | F | 35 kg/3 mo | - | - | No | Yes |

| [39] | 1 | 56 | F | 15 kg | - | 2 yr | Yes, non-compliance | Yes, corticosteroids |

| [40] | 1 | 38 | M | Yes | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [41] | 1 | 50 | M | 13 kg/2 mo | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [15] | 1 | 37 | F | Yes | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [13] | 1 | 26 | F | - | 19.9 | 2 yr | Yes, non-compliance | Yes, prednisone |

| [42] | 1 | 30 | F | 15 kg/3 yr | - | 0 | No | Yes |

| [8] | 2 | 75, 55 | M, F | Yes, - | 14.7, - | 0, 0 | No, No | Yes |

| [43] | 1 | 36 | F | 4 kg/9 d | 16.3 | 0 | No | Yes |

| [44] | 1 | 58 | M | 15 kg | 17.3 | 0 | No | Yes |

BMI: Body mass index; CD: Celiac disease; GFD: Gluten-free diet.

Among the 42 cases, the median age was 50 years (range 23 to 83), which was higher in males (62 vs 45, P = 0.002), and there was a female predominance (female: male ratio 2:1). Amid the reviewed cases, only 5 were previously known CD patients, in whom poor adherence to diet was noted, while the remaining 37 (88.1%) were diagnosed based on their presentation as CC.

Clinical manifestations

From a clinical point-of-view, all patients reported diarrhea and, in about two thirds of them, significant weight loss was documented. In only 1 case it is mentioned that the weight was not affected, while in the rest of the cases presented, this information was missing. Also, signs of dehydration were described, like tachycardia, functional renal impairment or arterial hypotension (Table 1).

Interestingly, the malabsorption syndrome associated with CC lead to clinical pictures, like altered hemostasis (bleeding diathesis or thrombosis) in 4 patients, neurologic manifestations (tetany, paresthesia, neuropathy or quadriparesis, likely in the setting of hypocalcemia or hypokalemia) in 6 patients, and cardiovascular involvement (firing of an implantable cardiac defibrillator) in 1 patient.

A possible CC precipitating factor was described in 11/42 of the cases, as follows: trauma - 1, surgery - 3 (one for small bowel obstruction by Meckel diverticulum, two after pancreatico-duodenectomy/Whipple procedure), pancreatitis - 1, infections - 4 (Clostridium difficile colitis - 1, herpes simplex esophagitis - 1, urinary tract infection - 1, cytomegalovirus infection - 1), birth - 1, or Bell’s palsy - 1.

Altogether six out of the 42 cases associated with other autoimmune diseases, namely 2 with type 1 diabetes mellitus, 1 with rheumatoid arthritis, 1 with autoimmune hypothyroidism, 1 with autoimmune hepatitis and 1 other with Sjogren and Raynaud's disease.

Laboratory data and diagnostic approach

Anemia, prolonged international normalized ratio, hypoalbuminemia, hypokalemia and hypocalcemia were seen in a substantial number of cases, reflecting the malabsorptive state in these patients. Metabolic acidosis was also reported in a high proportion of cases. Anemia, hypoalbuminemia, coagulation disturbances and deficiency of vitamin B12, vitamin D or folate were found when tested. Laboratory work-ups of reported cases is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Celiac disease published cases – paraclinical characteristics

| Index | No |

Diagnosis |

Hemogram | Coagulation | |||

| Biopsy | EMA | tTG | DGP/AGA | ||||

| [26] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | - | P, 608 U | - | Hb – L (7.8 g/dL), PLT – L | INR – H (2.1), aPTT – H (45 s) |

| [22] | 1 | Yes | P | P | P | - | - |

| [10] | 1 | Yes | - | P (> 100 U) | - | Hb – H (15.8 g/dL) | - |

| [27] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | - | P (99 U/mL) | - | Hb – L (9.3 g/dL) | INR – H (3.2) |

| [28] | 1 | Yes | - | P (132 U) | - | Hb – L (4.8-12.2 g/dL) | INR – H (1.3) |

| [25] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | - | P (48 U) | P/(39 U) | Hb – L (11.0 g/dL) | - |

| [12] | 1 | Yes | - | - | - | - | INR – H (3.5) |

| [29] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 4 | - | P (19 UI/mL) | - | - | - |

| [30] | 2 | Yes | P (3+) | P (200 RU/mL) | - | Hb – L (8.1 g/dL), PLT – L (180000/dL) | - |

| Yes | P (+1) | P (200 RU/mL) | Hb – L (7.6 g/dL), PLT – L (156000/dL) | - | |||

| [31] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 4 | P | P (> 200 U/mL) | P | Hb – L (8.7 g/dL) | - |

| [32] | 1 | Yes | - | - | - | Hb – L | - |

| [33] | 1 | Yes | P (> 1/1280) | - | - | Hb – NR (12.3 g/dL) | - |

| [34] | 1 | Yes | P | N | - | - | - |

| [35] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3 | N | N | N | Hb – NR (12.4 g/dL), PLT – L (160000/dL) | - |

| [16] | 12 | Yes 12/12, ≥ Marsh 3a | - | P, 10/11 | - | - | - |

| [14] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3 | P (92 U/mL) | - | P/(20 U/mL) | - | - |

| [23] | 1 | Yes | P (1:160) | P (15 EU/mL) | - | - | - |

| [36] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3b | - | P (33.9 U/L) | P/(41.9 U/L) | Hb – NR, PLT – L (94000/dL) | - |

| [37] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 4 | - | P (> 200 U/mL) | - | Hb – L (4.7 g/dL) | - |

| [38] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | P | P | - | Hb – L (7.2 g/dL), PLT – L (257000/dL) | INR – H (> 1.5), aPTT – H (154 s) |

| [39] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 4 | N | N | - | - | - |

| [40] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | P (35.9 U) | P (20.6 U) | - | Hb – NR (15.2 g/dL) | INR – H (1.6) |

| [41] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3 | P (158.7) | P (> 200 U/mL) | - | Hb - L (9.4 g/dL) | - |

| [15] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3 | P | P | AGA P | Hb - L (8 g/dL) | - |

| [13] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | - | P (23.4, positive > 12) | AGA P (27.4) | HT - L (18%) | PT < 10% |

| [42] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3b | - | - | AGA P (IgA 63.4, IgG 111.1) | Hb - L | - |

| [8] | 2 | Yes, Marsh 3a; Yes, Marsh 3b | P; P | - | AGA N; AGA P | Hb - L (5.9 /dL); Hb - L (7.9 /dL) | PT prolonged (19 s); PT prolonged (18 s) |

| [43] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | - | - | - | Hb - L | - |

| [44] | 1 | Yes, Marsh 3c | P (1:640) | P (142) | AGA P | Hb - L (11.6 g/dL) | INR – H (1.6) |

L: Low; H: High; N: Normal; M: Masculine; Hb: Hemoglobin; P: Positive, N: Negative: NR: Normal ranges, HT: Hematocrit; AGA: Anti-gliadin antibodies; aPPT: Activated partial thromboplastin time; CD: Celiac disease; DGP: Anti-deamidated gliadin antibodies; EMA: Anti-endomysial antibodies; INR: International normalized ratio; PLT: Platelets; PT: Prothrombin time; tTG: Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies.

Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody (tTG) testing was noted in 23 cases, yielding 87% positivity. Anti-endomysial antibodies (EMA) were positive in 15 out of 17 CC cases reporting this determination (88.2%). Some of the patients were diagnosed using anti-gliadin antibodies (AGA), while in three articles, no CD-specific serology was reported. Naturally, the laboratory tests used varied widely.

Small bowel biopsy to confirm CD was performed in 100% of the adult CC cases analyzed. Notably, the CD histological intestinal pattern was advanced, classified as Marsh 3 and 4. A clear distribution of Marsh stages (3 a/b/c) could not be done because of the insufficient data reported in the articles regarding the histological features of biopsies.

Treatment and evolution under gluten-free diets

All patients required hospitalization with fluid resuscitation, correction of acid-base or electrolyte imbalances and nutritional support. There was good evolution with the GFD in the reported cases, except one, in whom death was recorded due to refeeding syndrome. In about one in five patients (8/42 - 19%), treatment by steroids was noted for CC management.

DISCUSSION

Despite being first described in 1953[6-8], it was not until 2010 that CC had its first diagnostic criteria set, proposed by Jamma et al[16]. Characterizing a case series of 12 patients, the CC was defined as an acute onset or rapid progression of the gastrointestinal symptomatology attributable to CD, requiring hospitalization and/or parenteral nutrition along with at least two of the following: (1) Signs of severe dehydration, including hemodynamic instability and/or orthostatic changes; (2) Neurologic dysfunction; (3) Renal dysfunction, with creatinine levels > 2.0 g/dL; (4) Metabolic acidosis, pH < 7.35; (5) Hypoproteinemia (albumin level < 3.0 g/dL); (6) Abnormal electrolyte levels, including hypernatremia/hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, or hypomagnesemia; and (7) Weight loss > 5 kg.

CC is only rarely encountered in clinical practice, having an estimate of under 1% of all CD cases[16]. Only case reports and small case series have been reported so far in the literature. We herein collected data on 42 adult CC cases (all fulfilling the diagnostic criteria proposed by Jamma et al[16]), and aimed to summarize the characteristics of these patients with regards to clinical, laboratory and histological data, and their outcome under GFD.

Among the 42 CC cases, there was a female predominance (2:1), which parallels the higher frequency of CD seen in women (2.3:1)[17]. CC was the inaugural feature of CD in 37/42 cases, while the remaining five were previously diagnosed CD patients in whom non-compliance probably triggered the CC. In these known nonadherent to diet CD patients, a differential diagnosis with refractory CD should be considered, as this also can have a poor outcome[18].

From a clinical point-of-view, the CC cases included in this review presented with severe diarrhea, weight loss and sometimes hemodynamic instability. Most frequent laboratory alterations reported were metabolic acidosis, anemia, hypocalcaemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypokalemia, a consequence of the profound malabsorptive state. In some cases, the electrolyte imbalances led to neurologic or cardiologic manifestations, which could be the main presenting feature in CC; a high index of suspicion is needed among physicians with regard to these atypical and very rare presentations, as they were previously shown to have poor awareness in regard to CD non-intestinal features[19]. In addition, CC can also present with bleeding diathesis, which was the case for 4/42 of the reviewed cases; as previously reported, hemorrhagic events in CD patients encompass a wide range of clinical manifestations, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, hemoptysis, epistaxis, hematuria, hematomas or ecchymosis[20].

This acute, stormy presentation of CD has been postulated by some authors to be triggered by a stimulus, such as surgery, infection or pregnancy[16]. Among the 42 reviewed cases, one in four patients had a recent major medical event/intervention, which could have worsened the baseline pathology; it is, however, still early to confirm a concrete link. Moreover, we have to consider the possibility that an anterior or associated intestinal infection makes the differential diagnosis with CC very difficult. It might even be useful to consider the concomitance of an infection with intestinal tropism as an exclusion criterion for CC in CD patients, or to carefully consider a differential diagnosis in such cases.

Regarding a CD-positive diagnosis, although some cases have been diagnosed using AGA as a serological marker, most of the patients were either tTG- or EMA-positive. Small bowel biopsies were carried out in all patients, revealing enteropathy with different grades of severity, most with advanced histology changes (Marsh 3c stage). Although the exact distribution for sub-stages Marsh 3 a/b/c could not be done due to insufficient histological data from the case reports, its usefulness is questioned in a recent consensus paper, which concluded that sub-classification of the Marsh 3 stage should be abandoned[21].

Evolution under GFD was favorable in all patients, with improved clinical and biological status, except one reported death due to refeeding syndrome[22]. Steroid use was reported in some of the CC patients. Recent reports, however, question the role of steroids in CC[23], and this is backed up by case reports when ongoing immunosuppression with corticosteroids and azathioprine for autoimmune hepatitis[24] or prednisone for Bell’s palsy[24] did not prevent CC occurrence. There is also the concern of increased electrolyte depletion under corticosteroid treatment[22].

In conclusion, CC is a rare but severe and possibly life-threatening clinical form of CD. We herein present a review of adult CC cases reported in the literature to date, aiming to raise awareness about this entity by better defining these patients’ profile in regards to possible triggers, clinical presentation, laboratory workup alterations, management and outcome.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Celiac disease (CD) is well-recognized as a clinical chameleon, which is responsible for the high under-diagnosis rates of this common digestive condition. One of its presenting features is celiac crisis (CC), a potentially life-threatening acute malabsorptive state accompanied by metabolic and electrolyte disturbances and hemodynamic instability, usually requiring hospitalization and intensive care. Only a handful of case reports so far have been published in the literature, both in adults and children, and current available guidelines do not make any mention of this condition.

Research motivation

We aimed to perform a systematic review focused on CC in order to better delineate the possible triggers, clinical features, diagnostic work-ups and treatment measures. Only case reports or case series were published so far in the literature. Therefore, another objective was raising awareness about this condition as a possible heraldic feature of CD.

Research objectives

The main objective was to get a clear characterization of CC by summarizing all case reports with regard to clinical manifestations, laboratory data, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Also, we intended to gain some insight about the possible trigger factors of CC.

Research methods

For this purpose, we performed a systematic review of published case reports by searching the literature in two major databases, PubMed and EMBASE. All abstracts meeting the inclusion criteria were processed, and relevant articles were read in their full text forms and further analyzed for the specific objectives.

Research results

Our review summarizes the available literature on the occurrence of CC in adults, which included 42 cases reported in 29 articles. Common clinical features (profuse diarrhea, hemodynamic instability, weight loss, renal impairment) and particular ones (neurologic, cardiovascular or hematologic) were described, along with possible triggers (infections, surgery, pregnancy). Besides the laboratory alterations secondary to the acute malabsorptive state, the diagnostic approach included CD serology testing and histology. Management and outcome, referring to intensive care support, the need for steroids, and evolution under a gluten free diet were also analyzed.

Research conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this review is the first to summarize clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches of a rare but potentially life-threatening presenting feature of CD using an extensive analysis of currently available data. In addition to a clear definition and description of the characteristics of CC, the gaps in our current understanding of this condition were also outlined.

Research perspectives

This research presents the main characteristics of CC occurrence in adult CD patients and also emphasizes there is a need to increase awareness of this condition. Further research is warranted to elucidate the pathological mechanism that triggers CC.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: PRISMA checklist was assessed for this article.

Peer-review started: November 1, 2018

First decision: November 22, 2018

Article in press: December 12, 2018

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ahmed M, Gassler N, Nenna R, Rostami-Nejad M, Rostami K, Vorobjova T S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Song H

Contributor Information

Daniel Vasile Balaban, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 020021, Romania.

Alina Dima, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 020021, Romania. alina_dima@outlook.com.

Ciprian Jurcut, Department of Internal Medicine, Dr. Carol Davila Central Military Emergency University Hospital, Bucharest 010825, Romania.

Alina Popp, Department of Pediatrics, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 020021, Romania; Alessandrescu-Rusescu Institute for Mother and Child Health, Bucharest 020395, Romania; Center for Child Health Research, University of Tampere and Tampere University Hospital, Tampere 33521, Finland.

Mariana Jinga, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 020021, Romania.

References

- 1.Bosca-Watts MM, Minguez M, Planelles D, Navarro S, Rodriguez A, Santiago J, Tosca J, Mora F. HLA-DQ: Celiac disease vs inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:96–103. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656–76; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, Card TR, Ciacci C, Ciclitira PJ, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M, Holdoway A, van Heel DA, Kaukinen K, Leffler DA, Leonard JN, Lundin KE, McGough N, Davidson M, Murray JA, Swift GL, Walker MM, Zingone F, Sanders DS BSG Coeliac Disease Guidelines Development Group; British Society of Gastroenterology. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63:1210–1228. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman HJ. Endocrine manifestations in celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8472–8479. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, Troncone R, Giersiepen K, Branski D, Catassi C, Lelgeman M, Mäki M, Ribes-Koninckx C, Ventura A, Zimmer KP ESPGHAN Working Group on Coeliac Disease Diagnosis; ESPGHAN Gastroenterology Committee; European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen DH, Di Sant'Agnese PA. Idiopathic celiac disease. I. Mode of onset and diagnosis. Pediatrics. 1953;11:207–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Sant'Agnese PA. Idiopathic celiac disease. II. Course and prognosis. Pediatrics. 1953;11:224–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozaslan E, Köseoğlu T, Kayhan B. Coeliac crisis in adults: report of two cases. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:363–365. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200412000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:636–651. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiwari A, Qamar K, Sharma H, Almadani SB. Urinary Tract Infection Associated with a Celiac Crisis: A Preceding or Precipitating Event? Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;11:364–368. doi: 10.1159/000475921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sood A, Midha V, Makharia G, Thelma BK, Halli SS, Mehta V, Mahajan R, Narang V, Sood K, Kaur K. A simple phenotypic classification for celiac disease. Intest Res. 2018;16:288–292. doi: 10.5217/ir.2018.16.2.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Almeida Menezes M, Cabral V, Silva Lorena SL. Celiac crisis in adults: a case report and review of the literature focusing in the prevention of refeeding syndrome. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:67–68. doi: 10.17235/reed.2016.4073/2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutiérrez S, Toro M, Cassar A, Ongay R, Isaguirre J, López C, Benedetti L. Celiac crisis: presentation as bleeding diathesis. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2009;39:53–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atikou A, Rabhi M, Hidani H, El Alaoui Faris M, Toloune F. Celiac crisis with quadriplegia due to potassium depletion as presenting feature of celiac disease. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30:516–518. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selen T, Ince M, Celik S, Cankurtaran RE KF. Gluten Sensitive Enteropathy Presenting with Celiac Crisis as the Initial Presentation: Case Report. Turkiye Klin J Gastroenterohepatol. 2014;21:60–62. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamma S, Rubio-Tapia A, Kelly CP, Murray J, Najarian R, Sheth S, Schuppan D, Dennis M, Leffler DA. Celiac crisis is a rare but serious complication of celiac disease in adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardella MT, Fredella C, Saladino V, Trovato C, Cesana BM, Quatrini M, Prampolini L. Gluten intolerance: gender- and age-related differences in symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:15–19. doi: 10.1080/00365520410008169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowinski SA, Christensen E. Epidemiologic and therapeutic aspects of refractory coeliac disease - a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2016;63:A5307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jinga M, Popp A, Balaban DV, Dima A, Jurcut C. Physicians' attitude and perception regarding celiac disease: A questionnaire-based study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:419–426. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2018.17236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dima A, Jurcut C, Manolache A, Balaban DV, Popp A, Jinga M. Hemorrhagic Events in Adult Celiac Disease Patients. Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2018;27:93–99. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.271.cld. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rostami K, Marsh MN, Johnson MW, Mohaghegh H, Heal C, Holmes G, Ensari A, Aldulaimi D, Bancel B, Bassotti G, Bateman A, Becheanu G, Bozzola A, Carroccio A, Catassi C, Ciacci C, Ciobanu A, Danciu M, Derakhshan MH, Elli L, Ferrero S, Fiorentino M, Fiorino M, Ganji A, Ghaffarzadehgan K, Going JJ, Ishaq S, Mandolesi A, Mathews S, Maxim R, Mulder CJ, Neefjes-Borst A, Robert M, Russo I, Rostami-Nejad M, Sidoni A, Sotoudeh M, Villanacci V, Volta U, Zali MR, Srivastava A. ROC-king onwards: intraepithelial lymphocyte counts, distribution & role in coeliac disease mucosal interpretation. Gut. 2017;66:2080–2086. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammami S, Aref HL, Khalfa M, Kochtalli I, Hammami M. Refeeding syndrome in adults with celiac crisis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:22. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1566-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta S, Kapoor K. Steroids in celiac crisis: doubtful role! Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:756–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al Shammeri O, Duerksen DR. Celiac crisis in an adult on immunosuppressive therapy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:574–576. doi: 10.1155/2008/453520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bul V, Sleesman B, Boulay B. Celiac Disease Presenting as Profound Diarrhea and Weight Loss - A Celiac Crisis. Am J Case Rep. 2016;17:559–561. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.898004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forrest EA, Wong M, Nama S, Sharma S. Celiac crisis, a rare and profound presentation of celiac disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:59. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0784-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen A, Linz CM, Tsay JL, Jin M, El-Dika SS. Celiac Crisis Associated with Herpes Simplex Virus Esophagitis. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:e159. doi: 10.14309/crj.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bou-Abboud C, Katz J, Liu W. Firing of an Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator: An Unusual Presentation of Celiac Crisis. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:e137. doi: 10.14309/crj.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sbai W, Bourgain G, Luciano L, Brardjanian S, Thefenne L, Al Shukry A, Coton T. Celiac crisis in a multi-trauma adult patient. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:e31–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yilmaz B, Aksoy EK, Kahraman R, Yaprak M, Sıkgenc M, Dayan R, Eren I, Efe C. Atypical Presentation of Celiac Disease in an Elderly Adult: Celiac Crisis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1712–1714. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mrad RA, Ghaddara HA, Green PH, El-Majzoub N, Barada KA. Celiac Crisis in a 64-Year-Old Woman: An Unusual Cause of Severe Diarrhea, Acidosis, and Malabsorption. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;2:95–97. doi: 10.14309/crj.2015.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akbal E, Erbağ G, Binnetoğlu E, Güneş F, Bilen YG. An unusual gastric ulcer cause: celiac crisis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2014;126:661–662. doi: 10.1007/s00508-014-0588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toyoshima MT, Queiroz MS, Silva ME, Corrêa-Giannella ML, Nery M. Celiac crisis in an adult type 1 diabetes mellitus patient: a rare manifestation of celiac disease. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2013;57:650–652. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302013000800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parry J, Acharya C. Celiac crisis in an older man. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1818–1819. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishna K, Krishna SG, Coviello-malle JM, Yacoub A, Hutchins LF. Celiac crisis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly E, Cullen G, Aftab AR, Courtney G. Coeliac crisis presenting with cytomegalovirus hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:793–795. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000224471.28626.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandan S, Ahmad D, Hewlett AT. Las Vegas: American College of Gastroenterology; 2016. Celiac Crisis: A Rare Presentation of Celiac Disease in Adults. Proceedings of the American College of Gastroenterology annual meeting 2016; 2016 Oct 14-19; Las Vegas, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Leon LB, Becker SC da C, Appel-da-Silva MC, D’Incao RB, Tovo CV. Celiac crisis and hemorrhagic diathesis in an adult. Sci Med (Porto Alegre) 2014;24:284–287. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira R, Pina R, Cunha N, Carvalho A. A Celiac Crisis in an Adult: Raising Awareness to a Life-Threatening Condition. EJCRIM. 2016:3. doi: 10.12890/2016_000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magro R, Pullicino E. Coeliac crisis with severe hypokalaemia in an adult. Malta Med J. 2012;24:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kizilgul M, Kan S, Celik S, Apaydin M, Ozcelik O, Beysel S, Cakal E, Ozbek M, Karaahmet F, Delibasi T. Celiac crisis in an adult type 1 diabetes mellitus patient presented with diarrhea, weight loss and hypoglycemic attacks. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2017;37:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta T, Mandot A, Desai D, Abraham P, Joshi A. Celiac crisis with hypokalemic paralysis in a young lady. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:259–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf I, Mouallem M, Farfel Z. Adult celiac disease presented with celiac crisis: severe diarrhea, hypokalemia, and acidosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:324–326. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200004000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.do Vale RR, Conci NDS, Santana AP, Pereira MB, Menezes NYH, Takayasu V, Laborda LS, da Silva ASF. Celiac Crisis: an unusual presentation of gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Autops Case Rep. 2018;8:e2018027. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]