Abstract

Background:

The herb, Commelina paludosa (CP) Blume (Family-Commelinaceae) is medicinally used by the traditional practitioners in Bangladesh. However, there is a lack of scientific evidence on this medicinal herb.

Aim and Objectives:

This study aimed to evaluate the phytochemical and pharmacological activities of CP (ethanol [ECP], chloroform [CCP] and n-hexane [NHCP] of whole-plant extracts).

Materials and Methods:

For this antioxidant, antimicrobial, antidiarrheal and antipyretic activities of crude extracts of CP were conducted by 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging, disc diffusion and serial dilution, castor oil-induced diarrhea and yeast powder-induced pyrexia methods respectively.

Results and Observation:

The results suggest that all the fractions significantly scavenged DPPH radicals. In the disc diffusion test, the zones of inhibition were observed within the range of 7 mm to 30.67 mm at 500 mg/disc. The highest zones of inhibition were observed by ECP, CCP and NHCP against Bacillus azotoformans, Lactobacillus coryifomis and Salmonella typhi respectively. NHCP was found to exert stronger antibacterial effect than the ECP and CCP.

Conclusion:

Minimum inhibitory concentrations were detected within the range of 31.25 and 250 μg/ml. Moreover, the crude fractions also showed significant (P < 0.05) antidiarrheal and antipyretic activities in Swiss mice. CP may be a good source of therapeutic components.

Keywords: Commelina paludosa, organic fractions, pharmacological activities, phytochemicals, plant-based remedies

Introduction

Natural products are one of the potential sources of various chemical compounds in the prevention and treatment of human diseases. In modern medicine, the contribution of plant-based products is estimated about 25%–30%. Doubtless, medicinal plants have been widely studied for the discovery of antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and other therapeutic classes of chemical entities.[1] In general, the herbal drugs are considered as effective as the synthetic drugs with lower side effects.[2]

Bangladesh is a subtropical country which is rich with medicinal plants. Commelina paludosa (CP) Blume (Family-Commelinaceae) is a herbaceous plant, habitat in India, Burma, Bhutan, Southern China and some regions in Bangladesh. In some areas in Bangladesh, CP leaf extract is taken orally 2–3 times daily to treat dysentery.[3] Thus, this plant may be one of the good sources of important therapeutic components, especially for treating microbial and related other infections. The present study was aimed to investigate antibacterial, antidiarrheal, antioxidant and antipyretic activities of crude fractions of CP.

Materials and Methods

Collection, identification and preparation of plant material

CP was collected from the Chittagong hill tracts of Rangamati, Bangladesh, in the month of December. The plant sample (whole plant) was identified by the scientist of Bangladesh Forest Research Institute Herbarium, Chittagong. Then, the plant (whole) materials were shade-dried at temperature not exceeding 40°C and ground. The powder was preserved in an amber color airtight container until the extraction commenced.

Extraction and fractionation

About 75 g of coarse powder was extracted with absolute ethanol (700 ml) with a Soxhlet extractor (Quickfit, England) for 18 h. The extract was then filtered with filter paper (Whatman No. 1) and kept at room temperature to evaporate the solvent. The yield of the crude CP extract was 7.05%. The extract was subjected to successive fractionation with ethanol CP (ECP), chloroform CP (CCP) and n-hexane CP (NHCP). Percentage yields of ECP, CCP and NHCP were 5.20, 2.54 and 3.32 g respectively.

Preliminary screening for phytoconstituents

The findings of the preliminary phytochemical screenings were assessed according to Sultana et al.[4]

Chemicals and reagents

Required chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from Merck, Germany. The standards, ascorbic acid, azithromycin, loperamide and paracetamol were provided by the Square Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Bangladesh.

Bacterial strains

Antibacterial test was done against five Gram positive (e.g., Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus coryifomis, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus azotoformans) and five Gram negative (e.g., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi, Klebsiella pneumonia and Vibrio cholerae) strains. All the strains were provided by the Microbiology laboratory, BGC trust university, Chittagong, Bangladesh and were maintained in agar medium.

Experimental animals and ethical approval

Adult male Swiss albino mice (20–25 g bw) were purchased from Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR) in Chittagong and were housed in Animal house of Department of Pharmacy, Southern University, Bangladesh and University of Science and Technology, Chittagong (USTC), in a controlled environment (temperature: (26.0 ± 1.0°C, relative humidity: 55%–65% and 12 h light/12 h dark cycle) and free accessed to BCSIR formulated pellets and water. All protocols for animal experiment were approved by the USTC animal ethics committee (Ethical approval No. 16-0463/2016).

Screening for antioxidant activity

1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging method: The antioxidant activity was conducted according to the method described by Islam et al.[5] A stock solution of the plant extracts was prepared and diluted with ethanol with a concentration range from 10 to 100 μg/ml. In the diluted sample (0.3 ml), 2.7 ml of 0.004% DPPH ethanolic solution was added. Ethanol was used only in control tubes. The mixture was shaken properly and allowed to stand at dark for 30 min to complete the reaction and absorbance was taken using spectrophotometer at 517 nm. The DPPH radical scavenging potential was calculated using the following equation:

% inhibition of DPPH• scavenging = [(Abr– Aar)/Abr] × 100

Where Abr and Aar are the absorbance of DPPH free radicals before and after of the reaction, respectively.

Anti-bacterial sensitivity test

Disc diffusion assay: The antibacterial activity test was performed using disc diffusion method.[6] The antibacterial activity of the crude fractions and the standard, azithromycin was determined by measuring the diameter of the zone of inhibition in millimeter. The experiment was carried out in triplicates.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations

Microdilution test: Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by microdilution method.[7] For this, the crude fractions of the extract were diluted within 2–512 μg/ml. 0.1 ml bacterial suspension (1–2 × 107 CFU/ml) was added in each tube. Then, the tubes were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The lowest concentration (highest dilution) of the extract that produced no visible bacterial growth (no turbidity) when compared with the control tubes were regarded as MIC.

Test for antidiarrheal activity

Castor oil-induced diarrheal model: Antidiarrheal activity of crude fractions of CP was tested in castor oil-induced diarrheal mice.[8] For this study, 25 mice were divided into five groups, five in each. Control group received 0.5% tween 80 (10 ml/kg) while standard group received loperamide (3 mg/kg). Test groups received ECP, CCP and NHCP at 500 mg/kg. All the treatment drugs were given through oral gavage. After 60 min of treatments, the animals were treated with 0.4 ml of castor oil and the latency period and diarrheic secretion were counted for 4 h.

Antipyretic activity test

Yeast-induced hyperthermia method: The antipyretic activity of plant fractions was tested by Adams et al.[9] with slight modification. For this experiment, pyrexia was induced by subcutaneous administration of yeast powder before 24 h. Rectal temperature was measured by using a digital thermometer. The induction of pyrexia was confirmed by the rise in temperature more than 0.5°C. The animals showed a rise in temperature <0.5°C was excluded from this study. There were five groups, each group consisted of five mice. The first group received distilled water (150 ml/kg, PO) as a negative control, the second group received paracetamol (150 mg/kg, PO) as a positive control, where the remaining groups received CP fractions at 500 mg/kg orally. After drug administration, rectal temperature was again recorded periodically at 1, 2 and 3 h.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and percentage (%). The data were analyzed by means of analysis of variance, followed by t-Student–Newman–Keuls's post hoc test (except antimicrobial) using the GraphPad Prism (version: 6.0) Software (GraphPad San Diego, California, USA. copyright © 1994–1999) considering 95% confidence interval at P < 0.05.

Results

According to Table 1, ECP, CCP and NHCP reveal the presence of glycosides, flavonoids, saponins and gum. ECP and CCP fractions also contain tannins.

Table 1.

Phyto-constituents found in the crude fractions of Commelina paludosa

| Phytoconstituents | Phyto-constituents extracts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ECP | CCP | NHCP | |

| Alkaloids | − | − | − |

| Glycosides | + | + | + |

| Steroids | − | − | − |

| Tannins | + | + | − |

| Flavonoids | + | + | + |

| Saponins | + | + | + |

| Reducing sugars | − | − | − |

| Gums | + | + | + |

+: Presence, −: Absence, ECP: Ethanol extract of C. paludosa, CCP: Chloroform extract of C. paludosa, NHCP: n-hexane extract of C. paludosa

In case of antioxidant test, at the concentration of 100 μg/ml ECP, NHCP and CCP of CP showed statistically significant (P < 0.05) inhibition of 56.20%, 61.85% and 51.44% relatively as compared to the standard (ascorbic acid) by 94.29% [Table 2]. The half maximal effective concentration50 of ECP, NHCP and CCP were 91.53, 82.7 and 98.39 μg/ml respectively, while for the standard it was 52.37 μg/ml.

Table 2.

Antioxidant activity of ethanol, chloroform and n-hexane extract of Commelina paludosa

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Percentage inhibition of DPPH activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECP | NHCP | CCP | AA | |

| 10 | 7.45 | 6.95 | 7.75 | 20.29 |

| 20 | 12.95 | 13.86 | 14.58 | 51.25 |

| 40 | 20.31 | 22.79 | 23.15 | 36.89 |

| 60 | 30.35 | 34.25 | 32.75 | 59.87 |

| 80 | 42.13 | 46.27 | 43.50 | 75.78 |

| 100 | 56.20 | 61.85 | 51.44 | 94.29 |

| EC50 | 91.53 | 82.70 | 98.39 | 52.37 |

AA: Ascorbic acid, EC50: Half maximal effective concentration, ECP: Ethanol extract of C. paludosa, CCP: Chloroform extract of C. paludosa, NHCP: n-hexane extract of C. paludosa, DPPH: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl

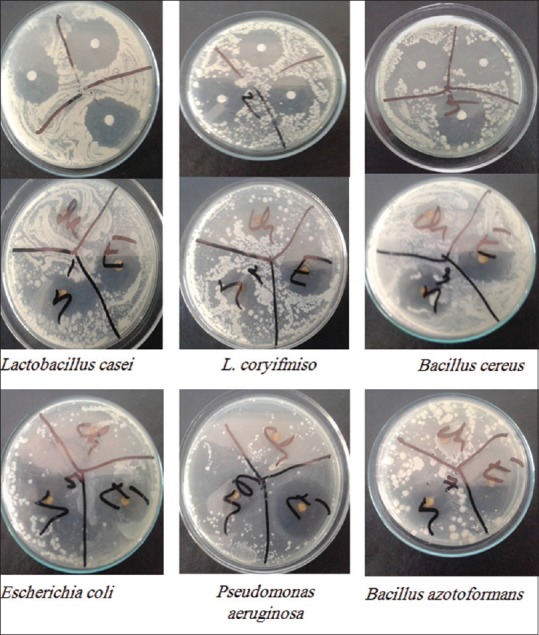

In the disc diffusion antibacterial activity test, the zones of inhibition were found within the range of 7–30.67 mm. A highest zone of inhibition (30.67 mm) was observed by ECP against B. azotoformans, while the lowest (7 mm) was observed by CCP against S. typhi. In case of ECP, zone of inhibition was observed as 29.00, 25.33, 30.00, 29.50 and 21.33 mm against L. casei, L. coryifomis, B. cereus, P. aeruginosa and S. typhi. respectively CCP showed zone of inhibition of 24.0 and 16.6 mm against L. coryifomis and B. cereus, while NHCP showed zones of inhibition of 21.33, 21.00, 24.00, 20.00, 28.00, 20.33 and 28.33 mm against L. casei, L. coryifomis, B. cereus, B. azotoformans, E. coil, P. aeruginosa and S. typhi, respectively. No inhibition was found against S. aureus, K. pneumonia and V. cholera [Table 3]. Images of zones of inhibition against the pathogenic bacteria have been shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Antibacterial activity of ethanol, chloroform and n-hexane extracts of Commelina paludosa

| Zone of inhibition (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test microorganism | ECP (500 mg/disc) | CCP (500 mg/disc) | NHCP (500 mg/disc) | AZ (30 mg/disc) |

| Gram-positive species | ||||

| Lactobacillus casei | 29.00±0.00 | NI | 21.33±0.58 | 31.68±0.58 |

| Lactobacillus coryifomis | 25.33±0.58 | 24.00±1.00 | 21.00±1.00 | 28.33±0.58 |

| Bacillus cereus | 30.00±0.00 | 16.6±0.58 | 24.00±1.00 | 32.00±1.73 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | NI | NI | NI | 34.00±1.73 |

| Bacillus azotoformans | 30.67±1.15 | NI | 20.00±1.00 | 36.33±0.58 |

| Gram negative species | ||||

| Escherichia coli | 28.00±1.00 | NI | NI | 30.33±0.58 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 29.50±0.71 | NI | 20.33±1.53 | 35.33±0.58 |

| Salmonella typhi | 21.33±1.53 | 7.00±0.00 | 28.33±0.58 | 30.00±0.58 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | NI | NI | NI | 26.33±0.58 |

| Vibrio cholerae | NI | NI | NI | 30.33±0.28 |

NI: No inhibition, AZ: Azithromycin, ECP: ethanol extract of C. paludosa, CCP: chloroform extract of C. paludosa, NHCP: n-hexane extract of C. paludosa

Figure 1.

Zones of inhibition by the crude extract and its fractions against the bacterial strain

ECP exhibited MIC of 31.25 μg/ml against L. casei, B. cereus and P. aeruginosa, then followed by S. typhi, L. coryifomis, B. azotoformans and E. coli by 62.5 μg/ml. In case of NHCP exhibited MIC of 125 μg/ml against L. casei and B. azotoformans, while against B. cereus, L. coryifomis and P. aeruginosa by 62.5 μg/ml and S. typhi by 31.25 μg/ml. On the other hand, the CCP exhibited MIC 125 μg/ml against L. coryifomis and 250 μg/ml against B. cereus and S. typhi [Table 4].

Table 4.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of the ethanol, chloroform and n-hexane extract of Commelina paludosa

| Test microorganisms | MICs (mg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ECP | NHCP | CCP | |

| Lactobacillus casei | 31.25 | 125 | - |

| Lactobacillus coryifomis | 62.50 | 62.5 | 125 |

| Bacillus cereus | 31.25 | 125 | 250 |

| Bacillus azotoformans | 62.50 | 125 | - |

| Escherichia coli | 62.50 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 31.25 | 62.50 | - |

| Salmonella typhi | 62.50 | 31.25 | 250 |

-: No inhibition, ECP: Ethanol extract of C. paludosa, CCP: Chloroform extract of C. paludosa, NHCP: n-hexane extract of C. paludosa, MICs: Minimum inhibitory concentrations

In case of antidiarrheal activity study, the ECP, CCP and NHCP of CP showed statistically significant (P < 0.05) antidiarrheal activity [Table 5]. The beginning of action and the total diarrheal feces were obtained by 1.17 h and 6.67, 1.13 h and 7.33 and 1.19 h and 7.67 at 500 mg/kg with ECP, CCP and NHCP respectively, where the onset of action and the total diarrheal faces of the standard, loperamide were 1.36 h and 5.33.

Table 5.

Antidiarrheal activities of ethanol, chloroform and n-hexane extract of Commelina paludosa

| Treatment groups | Mean latency period (min) | Number of faeces |

|---|---|---|

| Control (10 ml/kg, water) | 31.67±2.48 | 9.67±1.47 |

| Loperamide (3 mg/kg) | 96.33±4.67* | 5.33±1.08* |

| ECP (500 mg/kg) | 77.67±3.34* | 6.67±1.47 |

| CCP (500 mg/kg) | 73.67±3.63* | 7.33±1.47 |

| NHCP (500 mg/kg) | 79.67±5.35* | 7.67±1.08 |

Values are mean±SD (n=5), *P<0.05. ECP: ethanol Extract of C. paludosa, CCP: Chloroform extract of C. paludosa, NHCP: n-hexane extract of C. paludosa, SD: Standard deviation

Antipyretic activity was determined by yeast powder-induced acute fever in Swiss albino mice. The effect of the ECP, CCP and NHCP of CP on mice is presented in Table 6. In this test, the extract at a dose of 500 mg/kg statistically significantly (P < 0.05) attenuated hyperthermia in mice up to 3 h. Throughout the experiment, ECP at the dose of 500 mg/kg reduced temperature from 100.3 to 98.5°F, while the same dose of CCP reduced temperature from 100.61 to 98.4°F and the same dose of NHCP reduced temperature from 100.6 to 98.23°F. In case of antipyretic activity compared to the standard, paracetamol at a dose of 150 mg/kg reduced temperature from 100.9 to 98.1°F. The temperature gradually reduced at each 3 h, but the maximum reduction occurred at 1st h.

Table 6.

Anti-pyretic activity of ethanol, chloroform and n-hexane extract of Commelina paludosa

| Test groups | Rectal temperature in °F after 24 h of yeast injection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | 0 h | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | |

| Control (water) | 10 ml/kg | 100.53±0.18 | 100.47±0.68* | 100.17±0.11 | 100.23±0.08 |

| Paracetamol | 150 mg/kg | 100.9±0.25* | 98.1±0.32* | 98.2±0.25* | 97.87±0.33* |

| ECP | 500 mg/kg | 100.31±0.11 | 98.5±0.14* | 98.53±0.11* | 98.30±0.19* |

| CCP | 500 mg/kg | 100.61±0.14* | 98.4±0.19* | 98.23±0.11* | 98.33±0.11* |

| NHCP | 500 mg/kg | 100.6±0.14* | 98.23±0.14* | 98.33±0.18* | 98.23±0.04* |

Values are mean±SD (n=5), *P<0.05. ECP: Ethanol extract of C. paludosa, CCP: Chloroform extract of C. paludosa, NHCP: n-hexane extract of C. paludosa, SD: Standard deviation

Discussion

Oxidative stress means an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a biological system's ability to detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. To date, a number of diseases have been identified associated with oxidative stress, including neurodegenerative diseases such as Lou Gehrig's disease (also known as motor neurone disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, depression and multiple sclerosis,[10] cardiovascular diseases[11] and even development of cancers.[12,13] ROS can damage cell membrane as well as cellular macromolecules such as carbohydrates, proteins, lipids and genetic materials such as DNA and RNA.[14] The genotoxic and mutagenic effects caused by ROS may turn into cancer. DPPH is a popular antioxidant test method, where the stable DPPH radical is captured by a reducing agent called antioxidants. This test is popularly used to screen the antioxidant capacity of a variety of substances.[15] Undoubtedly, modern biomedicine has discovered that many of the most debilitating diseases, as well as the aging process itself, are caused by or associated with oxidative stress.[16] Plant-derived dietary supplements and drug products are in a much attention of the medicinal scientists to defend ROS and ROS-mediated phenomena.[5] The findings of the study suggest that all the fractions of CP exhibited a DPPH scavenging capacity, where best inhibition of this radical's activity was observed by the NHCP at the highest concentration tested. Thus, the n-hexane fractions may contain potent antioxidant compounds than the ECP and CCP.

Nowadays, drug resistance in the bacterial infections is a serious issue for public health.[1] The results suggest that the ECP, CCP and HNCP have potent antibacterial activity against the test strains (with some exceptions). In this case, the NHCP also exhibited better antibacterial activity than the ECP and CCP. In a recent study, Courtney et al.[17] suggests that ROS induction is an important antibacterial effect increasing factor. Thus, substance having pro-oxidative capacity may have antimicrobial activity. Evidence suggests that strong antioxidants are protective at low while pro-oxidative at high concentrations.[18] In this study, it was also found that the extract fractions exhibited antioxidant capacity at low concentrations, while antibacterial at high concentration. This can be easily seen for NHCP fraction, which exhibited strong antioxidant and anti-bacterial capacity than the other two fractions.

Diarrhea is the world's third highest killer disease characterized by an increase in the frequency of bowel movements, wet stool and abdominal pains.[19] Not only viruses and parasites but also bacteria are major pathogens-related that cause diarrhea in human. Salmonella spp. and some strains of E. coli are reported to cause diarrhea.[20] Inflammation in mucosal lining or brush border, caused by oxidative stress and pathogens may lead to develop inflammatory diarrhea. In the present study, ECP was found to act against E. coli, while all the other fractions against S. typhi. Thus, the antioxidant and antibacterial capacities of the crude fractions may connect the observed anti-diarrheal activities.

During fever present body temperature raises higher than the normal (around 98.6 F).[21] Both inflammation and microbial infection can cause fever. Lipopolysaccharide the bacterial substance present in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria[22] and some superantigens can cause rapid and dangerous fevers. These types of pyrogens can induce pro-inflammatory cytokines, activate macrophages and other leukocytes to secrete hydroxyl radical (OH), nitric oxide metabolites, superoxide (O2) and other reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), that can induce fever.[23] NHCP was found to reduce pyrexia statistically significant (P < 0.05) in test animals than the CCP and ECP. Moreover, bacterial infections causing serious diarrhea may cause fever. Thus, the radical scavenging along with the antibacterial and antidiarrheal capacity may be related to the extract-mediated antipyretic activity in experimental animals.

Glycosides are known for their various important biological effects, including antioxidant, antimicrobial and so on.[24] Flavonoids are better known for their potential antioxidant capacity. Many of them have been reported for pro-oxidative and antimicrobial activities.[5] According to Mao et al.,[25] saponins have varieties of pharmacological activities. In this study, all the fractions revealed the presence of the above-mentioned chemical groups, suggesting a possible link between the chemical groups and observed biological activities.

Conclusion

The crude fractions of CP exhibited significant antioxidant, antibacterial, antidiarrheal as well as antipyretic activity in the in vitro and in vivo test systems. The activities may be linked with each other. n-Hexane extract exhibited better activity than the ethanol and chloroform extracts. CP crude fractions, especially its n-hexane fraction, may contain potent antioxidant, antimicrobial, antidiarrheal and antipyretic compounds. Further studies are highly appreciated to isolate the responsible active compounds and elucidate the exact mechanism of action(s) for each biological activity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are owed to the authorities of Southern University Bangladesh and USTC, Bangladesh, for providing laboratory facilities to conduct this research.

References

- 1.Bouyahya A, Dakka N, Et-Touys A, Abrini J, Bakri Y. Medicinal plant products targeting quorum sensing for combating bacterial infections. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2017;10:729–43. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian A, Ramalingam K, Krishnan S, Christina AJ. Anti-inflammatory activity of Morus indica Linn. Iran J Pharmacol Ther. 2005;4:13–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman MA, Uddin SB, Wilcock CC. Medicinal plants used by Chakma tribe in hill tracts districts of Bangladesh. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2007;6:508–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sultana T, Chowdhury MM, Hoque FM, Junaid MS, Chowdhury MM, Islam MT. Pharmacological and phytochemical screenings of Bidens sulphurea cav. Eur J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2014;1:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Islam MT, Streck L, Paz MF, e Sousa JM, de Alencar MV, da Mata AM, et al. Preparation of phytol-loaded nanoemulsion and screening for antioxidant capacity. Int Arch Med. 2016;9:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman AU, Choudhary MI, Thomson WJ. London: Taylor & Francis E-Library; 2005. Bioassay Techniques for Drug Development; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoba FG, Thomas M. Study of antidiarrhoeal activity of four medicinal plants in castor-oil induced diarrhoea. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76:73–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams SS, Hebborn P, Nicholson JS. Some aspects of the pharmacology of ibufenac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1968;20:305–12. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel VP, Chu CT. Nuclear transport, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:215–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nijs J, Meeus M, De Meirleir K. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in chronic fatigue syndrome: Recent developments and therapeutic implications. Man Ther. 2006;11:187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: Have we moved forward? Biochem J. 2007;401:1–1. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handa O, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. Redox biology and gastric carcinogenesis: The role of Helicobacter pylori. Redox Rep. 2011;16:1–7. doi: 10.1179/174329211X12968219310756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Islam MT, Streck L, de Alencar MV, Cardoso Silva SW, da Conceição Machado K, da Conceição Machado K, et al. Evaluation of toxic, cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of phytol and its nanoemulsion. Chemosphere. 2017;177:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.02.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosewski G, Górna I, Bolesławska I, Kowalówka M, Więckowska B, Główka AK, et al. Comparison of antioxidative properties of raw vegetables and thermally processed ones using the conventional and sous-vide methods. Food Chem. 2018;240:1092–6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinatra ST, Oschman JL, Chevalier G, Sinatra D. Electric nutrition: The surprising health and healing benefits of biological grounding (Earthing) Altern Ther Health Med. 2017;23:8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtney CM, Goodman SM, Nagy TA, Levy M, Bhusal P, Madinger NE, et al. Potentiating antibiotics in drug-resistant clinical isolates via stimuli-activated superoxide generation. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1701776. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gim SY, Hong S, Kim MJ, Lee J. Gallic acid grafted chitosan has enhanced oxidative stability in bulk oils. J Food Sci. 2017;82:1608–13. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ezekwesili C, Obiora K, Ugwu O. Evaluation of anti-diarrheal property of crude aqueous extract of Occimum gratissimum L.(Labiatae) in rats. Biokem. 2004;16:122–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viswanathan VK, Hodges K, Hecht G. Enteric infection meets intestinal function: How bacterial pathogens cause diarrhoea. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:110–9. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kluger MJ. Fever: Its Biology, Evolution, and Function. Princeton University Press; 2015. p. 57. ISBN: 9781400869831. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou CC, Lin H, Chang CP, Huang WT, Lin MT. Oxidative stress and pyrogenic fever pathogenesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;667:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SK, Himaya SW. Triterpene glycosides from sea cucumbers and their biological activities. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2012;65:297–319. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416003-3.00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao KJ, Huang P, Zhang L, Yu HS, Zhou XZ, Ye XY, et al. Optimisation of extraction conditions for total saponins from Cynanchum wallichii using response surface methodology and its anti-tumour effects. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32:2233–7. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1371152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]