Abstract

Mycobacterium chimaera (M. chimaera) is a slow-growing nontuberculous mycobacteria usually associated with pulmonary infection in immunocompromised patients. Attributed to a specific brand of contaminated heater-cooler units used during cardiac surgery, M. chimaera has become a global public health concern due to disseminated infection affecting immunocompetent hosts. Given its nonspecific presenting symptoms and indolent course of infection, M. chimaera can mimic and be misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis. Increased awareness among the medical community and at-risk population should be maintained to facilitate more rapid diagnosis and prevent inappropriate treatment of this potentially devastating condition.

Keywords: mycobacterium chimaera, sarcoidosis, cardiac surgery, heater-cooler units

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium chimaera (M. chimaera) is a slow-growing nontuberculous mycobacteria that has recently become a global public health concern due to an invasive outbreak following cardiac surgery. This outbreak has been attributed to a specific brand of contaminated heater-cooler units (HCUs) used during surgery. Highly related genomes of M. chimaera have been isolated from geographically distant infections and from the manufacturer and are consistent with contamination from a single point source.1 Given the rarity of postoperative M. chimaera infection, its typically indolent course, and lack of physician awareness of the outbreak, it is often recognized very late or misdiagnosed.

CASE REPORT

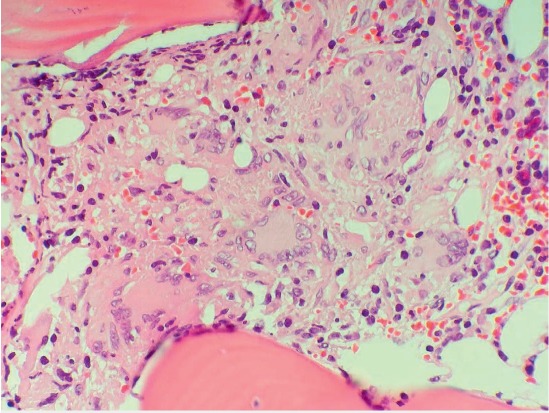

A 53-year-old woman with a history of bicuspid aortic valve and ascending aortic aneurysm presented with constitutional symptoms 2 years after undergoing bovine pericardial aortic valve and aortic root replacement. An infectious source was ruled out on multiple occasions with negative blood cultures, imaging studies (computed tomography scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis), and transesophageal echocardiogram. The patient had persistent cytopenias, marked splenomegaly, transaminitis, and constitutional symptoms including weight loss and fevers that led to expanding our differential diagnosis. She was noted to have non–parathyroid-hormone-related hypercalcemia and an elevated serum angiotensin converting enzyme level. A bone marrow biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1). At this point, a decision was made to treat her for presumed sarcoidosis, and she was started on immunosuppressants. Although constitutional symptoms initially improved, she developed fever and back pain 6 months later, leading to further workup. Spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed T10–T11 vertebral body inflammation concerning for infection, and a subsequent bone biopsy showed acid-fast bacilli. Culture of the specimen and blood cultures grew M. chimaera, and the patient was started on a macrolide-based, multidrug, antimicrobial regimen.

Figure 1.

Bone marrow biopsy showing noncaseating granulomas. Hematoxylin and eosin stain histologic sections of the bone marrow show multiple mediumsized non-necrotizing granulomas with giant cell formation (500×).

DISCUSSION

After the 2011 diagnosis of disseminated M. chimaera infection in a Swiss patient post cardiothoracic surgery, several similar cases have been recognized—all linked to contaminated HCUs of a specific brand. The infections are presumably spread during cardiac surgery by airborne transmission of aerosolized bacteria from the water tanks of these units,1 and it can take months to years to become clinically apparent. Symptoms are nonspecific and typically present as constitutional symptoms.2 M. chimaera is less virulent than other nontuberculous mycobacteria and is usually associated with pulmonary infections in immunosuppressed patients and patients with pre-existing lung conditions. Disseminated extrapulmonary infection—including prosthetic valve endocarditis, prosthetic vascular graft infection, sternotomy wound infection, and mediastinitis—has been seen in patients whose surgery involved a contaminated HCU. Embolic and immunologic sequela of disseminated infection have also been reported, such as splenomegaly, arthritis, osteomyelitis, cytopenia due to bone marrow involvement, chorioretinitis, hepatitis, nephritis, and myocarditis.2

It is noteworthy that nontubercular mycobacterial infections can cause both caseating and noncaseating granuloma. Since the clinical features and indolent course of M. chimaera infection can mimic sarcoidosis,3 it should be suspected in patients who have undergone cardiac surgery and present with unexplained fever and evidence of granulomatous disease. The presence of extrapulmonary disease and bone-marrow involvement, infrequent with sarcoidosis,4 may indicate the alternate diagnosis of M. chimaera—an important distinction given the potential consequences of inappropriate immunosuppressant therapy in an infected patient.

The diagnosis of M. chimaera infection is challenging because mycobacterial cultures are not part of the routine microbiological workup for cardiovascular infections. Identification of M. chimaera requires special cultures, and results are slow and have low sensitivity except when infected tissue is obtained by invasive sampling. Differentiation of mycobacteria at the species level requires specialized DNA sequence-based testing, and no direct nucleic-acid amplification or metagenomics assay is available for rapid detection of M. chimaera. Whole-genome sequencing has shown some utility in identifying iatrogenic M. chimaera infection, and further efforts are underway.5 A clarithromycin-based, multidrug, antimicrobial regimen is commonly used for treatment. Even so, eradication of M. chimaera is difficult, and outcomes have been poor despite long-term antimycobacterial and surgical therapies.2,3

Healthcare-associated infection due to M. chimaera is likely still under-recognized, and a high level of suspicion in the at-risk population should be maintained to facilitate more rapid diagnosis and prevent inappropriate treatment of this potentially devastating condition.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williamson D, Howden B, Stinear T. Mycobacterium chimaera Spread from Heating and Cooling Units in Heart Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 9;376(6):600–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1612023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohler P, Kuster SP, Bloemberg G et al. Healthcare-associated prosthetic heart valve, aortic vascular graft, and disseminated Mycobacterium chimaera infections subsequent to open heart surgery. Eur Heart J. 2015 Oct 21;36(40):2745–53. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan N, Sampath R, Abu Saleh OM et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium chimaera Infection After Cardiothoracic Surgery. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 16;3(3):ofw131. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brackers de Hugo L, Ffrench M, Broussolle C, Sève P. Granulomatous lesions in bone marrow: clinicopathologic findings and significance in a study of 48 cases. Eur J Intern Med. 2013 Jul;24(5):468–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Struelens MJ, Plachouras D. Mycobacterium chimaera infections associated with heater-cooler units (HCU): closing another loophole in patient safety. Euro Surveill. 2016 Nov 24;21(47):30404. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.46.30397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]