ABSTRACT

Background:

Illness and hospitalization are situations that increase the need for assistance and education. Poor education is currently the most common source of patient complaints in the health sector in Iran.

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives and recommendations of nurses to improve patient education.

Methods:

This research followed a qualitative exploratory design with a qualitative content analysis approach. The study participants, including eight head nurses and 16 staff nurses, were selected through purposive sampling. The data were collected through semistructured interviews, focus group sessions, and observations during 2016.

Results:

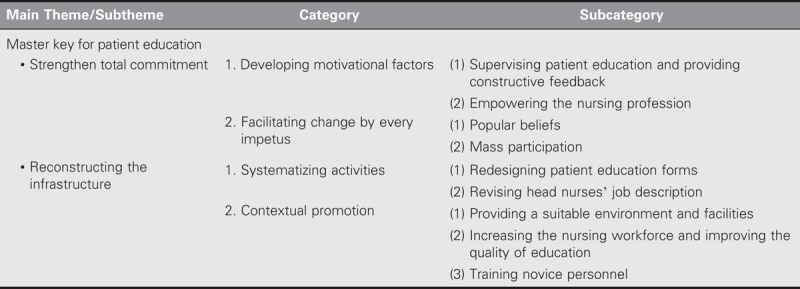

Coding and analysis of the data generated one main theme, two subthemes, and four categories. The subthemes were “strengthen total commitment” and “reconstructing the infrastructure,” and the categories were “developing motivational factors,” “facilitating change by every impetus,” “systematizing activities,” and “contextual promotion.”

Conclusions:

Study findings provide a complete picture of patient education and challenge managers to develop new strategies to plan and implement appropriate changes.

Key Words: patient education, nursing, qualitative research

Introduction

Humans try at every opportunity to learn specific knowledge and skills to increase their ability to cope with new situations. Illness and hospitalization are two situations that increase the need for assistance and education (Marcus, 2014; Rankin, Stalling, & London, 2005). Education, an interactive process in which learning takes place, is a basic human need (Fry, Ketteridge, & Marshall, 2009). Patient education is a process by which health professionals impart information to patients and their caregivers to improve health status and encourages involvement in decision making related to ongoing care and treatment. This process helps patients incorporate knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes that relate to specific or general medical topics, preventive services, the adoption of healthy lifestyles, correct use of medicine, and the care of disease and injuries at home (Dorland, 2011). Patient education aims to provide adequate and relevant clinical information with the goal of increasing the understanding of illness conditions and health-promoting behaviors (Seyedin, Goharinezhad, Vatankhah, & Azmal, 2015). The need for patient education has been widely recognized. The increasing prevalence of chronic illnesses, a limited number of hospital facilities, economic constraints on hospital fees, a high rate of hospital infections, and a need for better and safer care at home greatly increase the importance of patient education (Oermann, Harris, & Dammeyer, 2001). Increasing levels of literacy and development of mass media in recent years have encouraged recipients of healthcare to demand more information about their illness process and care plans (Scrutton, Holley-Moore, & Bamford, 2015). Well-educated patients are better able to understand and manage their own health and medical care throughout their lives (Marcus, 2014). Education is used to empower patients and is an important aspect of quality improvement, given that it is associated with improved health outcomes (Aghakhani, Nia, Ranjbar, Rahbar, & Beheshti, 2012). Education promotes patient compliance, satisfaction with care, healthy lifestyles, and self-care skills (Oyetunde & Akinmeye, 2015). In addition, patient education has also helped to decrease unpleasant patient experiences in hospitals, including reduced levels of pain and anxiety (Jafari, Olyari, Zareian, & Dadgari, 2015; Marcus, 2014; Seyadin et al., 2015).

The economic and financial burdens of health in terms of direct and indirect costs (absenteeism, social costs of disease) have increased to the extent that these threaten the financial viability of national and social insurance systems (Department of Health Systems Financing Health Systems and Services, World Health Organization, 2009). Because patients pay more for healthcare services, demand for high-quality care has increased (Oyetunde & Akinmeye, 2015). Every USD 1.00 spent on patient education on health-promoting behaviors is estimated to save as much as USD 3.00–4.00 in healthcare costs (Habel, 2002). In the United States, about USD $69–100 million is spent on problems that are caused by lack of education (Farzianpour, Hosseini, Mortezagholi, & Mehrbany, 2014).

Patient education has long been considered a major component of nursing care. Florence Nightingale attested to teaching as a function of nursing in her treatises on nursing in 1859 (cited in Oyetunde & Akinmeye, 2015). Nurses compose more than 70% of the healthcare team, and as a result, they play a critical role in patient education (Marcus, 2014). In fact, nurses have a greater access to and spend more time with patients than other members of the healthcare team or patient family members (Marcum, Ridenour, Shaff, Hammons, & Taylor, 2002). The role of nurses has changed over time, shifting from disease-oriented health education toward empowering patients to use their resources (including families, coping mechanisms, and personal knowledge) to attain health (Aghakhani et al., 2012). Therefore, nurses are in a key position to affect the lives of patients positively through education, with the potential to produce long-standing changes in patients’ lives (Seyadin et al., 2015). Although some studies revealed that nurses feel competent in the teaching role, others have pointed to lack of training and confidence as factors contributing to nurses’ reluctance to provide patient education (Oyetunde & Akinmeye, 2015). Kemppainen, Tossavainen, and Turunen (2013) reported that nurses consider health promotion important but obstacles associated with organizational culture prevent effective delivery. Although studies have been conducted in several countries, the process of patient education has not been well studied in Iranian health systems. Considering that patient education is a Joint Commission requirement for hospital accreditation (Marcus, 2014), exploring the perspectives and recommendations of richly experienced nurses with regard to the issue of patient education is a priority. The aim of this study was to document the perspectives and recommendations of nurses with regard to patient education.

Methods

Design

A qualitative exploratory design was used because of the ability of this type of design model to elicit the rich meaning in the perspectives of nurses.

Setting and Participants

Fasa is a county in Fars province, Iran, with a population of nearly 210,000 people and two hospitals. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method. Inclusion criteria for nurses were as follows: (a) have a baccalaureate or higher degree in nursing; (b) employed as a nurse, with at least 2 years of clinical experience; and (c) willing to participate. Participants included eight head nurses and 16 clinical nurses who had worked in medical, surgical, emergency, and pediatric departments.

Data Collection

The data were collected using semistructured in-depth interviews with participants who were head nurses (n = 8), focus group sessions with participants who were clinical nurses (n = 16), and observation in wards between April and October 2016. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim after each session. The eight face-to-face interviews with the eight head nurse participants were conducted for a duration of between 60 and 90 minutes each. The interviews began with general questions and moved toward more detailed questions based on each participant’s responses. The aim was to allow the interviewee to talk from her perspective. Examples of interview questions include “What are the problems with patient education?”, “How do you deal with these problems?”, “Can you provide any examples?”, and “Would you like to make any changes? If so, what would they be?” Interviews were continued until the two immediately preceding interviews gained no new information, at which time data saturation was assumed to have been reached. In addition, two focus group sessions were held with 16 nurse participants (eight nurses in each session). Focus group interviews cover range, specificity, depth, and context for a topic within a group interaction setting. These sessions lasted for approximately 90 minutes, and the participants were informed about the time and place of the sessions in advance. The participants were asked to reflect and talk about patient education barriers. The conversations were recorded. In addition, the observation method was used to view events, actions, norms, and values of the participants. In this study, our aim was identifying the problems that the healthcare team, including nurses, physicians, students, and others, faces in providing patient education. During the 5-month observation period, 24 patient education sessions (divided equally among morning, evening, and night) were observed. Observers did not participate; they focused on key events and activities during patient education. Field notes were written immediately after each observation. The semistructured observation guide included two sections: the context (including a description of the physical, material, and human resources in the ward) and the interactions between the healthcare team and patients (including the types and frequency of individual patient feedback, praise/reprimand ratios, and types and frequency of interactions between patients and the healthcare team).

Data Analysis

Conventional content analysis using Graneheim and Lundman’s method was used to analyze the data (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The contents of the data were documented by the research team (two associate professors who were qualified in qualitative research) immediately after each interview, focus group, and field observation. Transcripts and notes were read several times for a general understanding of participant statements relative to study objectives. Afterward, the final codes, including defining properties and relationships with one and another, were reviewed to reach consensus regarding the central unifying theme that emerged from the data. The research team extracted the meaning units or initial codes, which were merged and categorized according to similarities and differences. To minimize researcher bias, transcripts were read independently by the research team members. The lead researcher kept a reflexive diary to record and explore the interpretation process. MAXQDA Version 2 (Verbi GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used for data analysis.

Trustworthiness

The procedures used to ensure the trustworthiness of the study are described in the following. To ensure credibility, purposive sampling of participants, triangulation via use of different methods, different types of informants and different sites, and member checks of collected data were used and interpretations/theories were formed (coding and categories were shown to the participants with a request suggesting potential revisions/improvements). In addition, a team-based approach to data analysis was established to confirm credibility. To ensure transferability, background data were collected to establish the study context and the phenomenon in question was described in detail to allow comparison. To ensure dependability, the methodology was described in detail so that the study can be repeated. To ensure conformability, triangulation was employed to reduce the effect of investigator bias and a depth methodological description was provided to allow scrutiny of the integrity of research results. Prolonged engagement, varied experiences, and peer checking were other strategies used to improve the trustworthiness of this study (Graneherim & Lundeman, 2004; Shenton, 2004; Streubert Speziale & Rinaldi Carpenter, 2007).

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Research Council of the university (IR.FUMS.REC.1395.136). Before each interview, the participants were informed about the objectives, procedures, and voluntary nature of the study and that they could leave the study at any time. They were also informed about the anonymity and confidentiality of information. All participants gave informed consent.

Results

All of the participants were female, with a mean age of 31.1 ± 4.8 years (range = 22–41 years), a mean working experience of 4.9 ± 5.6 (range = 2–8) years, and BSc degrees in nursing.

Coding and analysis of the data generated one main theme, two subthemes, and four categories related to the perspectives and recommendations of participants with regard to patient education. The main theme was “master key for patient education.” Because a master key is able to open many different types of locks, these strategies were named the master key in the sense that they clarify and resolve the obstacles of patient education in hospitals. The subthemes were “strengthen total commitment” and “reconstructing the infrastructure,” and the categories were “developing motivational factors,” “facilitating change by every impetus,” “systematizing activities,” and “contextual promotion.” Themes are presented in Table 1 and explained in the following section.

TABLE 1.

Main Theme and Related Subthemes Extracted From the Perspectives of Participants

Strengthen Total Commitment

The first theme that emerged from the data was “strengthen total commitment” for patient education, with the following categories: “developing motivational factors” and “facilitating change by every impetus.” To overcome the obstacles of patient education, total commitment is necessary. In other words, nurses must be fully willing to devote the necessary time and energy to patient education and believe in it. Thus, administrators should strengthen institutional commitment by developing motivational factors and facilitating change by every impetus to achieve this milestone.

Developing motivational factors

The first category that emerged from the data was “developing motivational factors” for patient education, with the following subcategories: “supervising patient education and providing constructive feedback” and “empowering the nursing profession.”

1. Supervising patient education and providing constructive feedback

The participants acknowledged that including the implementation of patient education in annual personnel evaluations would be effective. In this regard, a head nurse said, “Managers should use carrots and sticks at the same times. Frequent punishment will not work.” In another case, a participant stated that “ignoring the nurses who enroll eagerly in patient education is not reasonable. Managers should appreciate their efforts, even with a smile or other acknowledgment.” Another participant also mentioned that “annual supervision at a specific time is not effective. Supervision should be intrusive and frequent.”

2. Empowering the nursing profession

The data obtained from the observations and tape recordings showed that nursing personnel complained about their authority and decision making in hospitals. They stated that other healthcare professionals such as physicians interfered in their territory, which was not pleasant and acceptable, destroyed their motivation, and may indirectly influence the quality of patient education. The following excerpt illustrates that nurses worry about their authority: “Favoritism is corrosive. Desecration, discrimination, lack of authority, and professionalism are disappointing in our hospital. First of all, we should strengthen our profession and define our territory by choosing a qualified matron, supervisors, and nursing personnel.”

Facilitating change by every impetus

The second category that emerged from the data was “facilitating change by every impetus,” with the subcategories of “popular beliefs” and “mass participation.”

1. Popular beliefs

The data obtained from multiple sources in this research showed that fostering shared beliefs was the first step to stabilizing change in society. The participants stated that all stakeholders should consider patient education a priority and take measures toward improving education. One participant mentioned: “A lasting change requires a general determination. All people in the organization from the top of pyramid to its base should actively participate.”

2. Mass participation

The findings showed that supervisors did not supervise the patient education process adequately. The observations also revealed that these supervisors did not pay attention to patient education in their rounds and did not consider this domain to be a priority. The following field note showed that practical involvement of the supervisors was not sufficient.

Observation 3: A supervisor with a clean, dark blue dress came to the pediatric ward one morning at 9 o’clock. After greeting and inquiring about the patients’ conditions, she went to the patients’ rooms with the head nurse and reviewed their conditions briefly one by one. However, nothing was mentioned about patient education during this supervisor’s round.

In this regard, a participant said, “A simple statement from a doctor is more effective than ten statements from a nurse.” Another participant added, “Our patients accept physicians’ rather than nurses’ prescriptions, so they should be encouraged to communicate with patients and explain the conditions to them.”

These categories were created by developing motivational factors and facilitating change by each impetus within one group, which was subsequently labeled under the subtheme “strengthen total commitment.”

Reconstructing the Infrastructure

The second subtheme from the data was “reconstructing the infrastructure” for patient education, with the following categories: “systematizing activities” and “contextual promotion.” Another solution for overcoming the obstacles of patient education is to rebuild or recreate a basic framework or foundation of patient education by systemizing activities and promoting the contextual factors.

Systematizing activities

The category “systematizing activities” for patient education contains the following subcategories: “redesigning patient education forms” and “revising head nurses’ job description.”

1. Redesigning patient education forms

The participants stated that having a specific form for patient education was necessary. They mostly mentioned that the current forms that were used in the hospital were obligatory for patients and quite time-consuming to complete. Thus, they recommended designing appropriate forms to improve patient education. The following narrative statement describes this subtheme:

We have many forms in the hospital that are time consuming to fill out. These forms should be modified based on each ward’s requirements and be completed at the patient’s bedside with an emphasis on patient education by nurses and physicians.

2. Revising head nurses’ job description

All of the head nurses mentioned that their job description needed to be revised by their hospitals based on new accreditation criteria. They stated that they were currently busy with the new accreditation criteria and standards, which led to their unintentional neglect of nursing care obligations such as patient education. One participant stated, “We are busy working on accreditation, supervision, physician rounds, and quality improvement and its paperwork. Unfortunately, we don’t have any time for patient education.”

Contextual promotion

The last subtheme from the data was “contextual promotion,” with the following subcategories: “providing a suitable environment and facilities,” “increasing the nursing workforce and improving the quality of education,” and “training novice personnel.”

1. Providing a suitable environment and facilities

Participants stated that a suitable environment was a prerequisite for patient education. High turnover in the wards and lack of suitable rooms for patient education were problems in this regard, as illustrated by field notes and interviews.

One evening at 5 o’clock, the nurses were busy working in the emergency ward (a room different from triage, where the patients are in sufficiently stable condition), which was overly crowded and noisy. There was little space among the beds and it was impossible to stand near the patients’ beds or communicate with them. Voices could not be heard due to crowdedness.

We need a quiet room in our wards for patient education to enhance its effectiveness. Concentration in a noisy environment is impossible for patients.

We need some facilities (such as video, TV, video software, and so on) to show various educational films on patient diets and medications while patients are in beds in their own rooms.

2. Increasing the nursing workforce and improving the quality of education

A shortage of nurses is yet another concern for patient education. In general, the nurse-to-patient ratios should be based on a standard minimum value to ensure a basic level of quality of care in hospitals. In this respect, one participant reported:

I think that patient education falls through the cracks due to the high workload in the hospital. The nursing shortage is really a crisis. When I have seven patients in each shift, there is no chance left for patient education.

Similarly, another participant stated, “Education session should be conducted individually based on patients’ characteristics and conditions. Education should be practical, objective, and based on patients’ mental capacities.”

3. Training novice personnel

Participants stated that newly graduated students were novices and that they started working in hospitals without experience. Thus, these new nurses needed to understand the importance of patient education and be thoroughly trained in this regard. One participant stated, “Frequent in-service education is recommended for nurses to improve their knowledge to educate patients efficiently.”

Systematizing activities and contextual promotion were categorized into one group, which was labeled “reconstructing the infrastructure” in this study.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore perspectives and recommendations of nurses with regard to improving patient education. Supervising patient education and providing constructive feedback were identified as the two subcategories. The participants highlighted the importance of frequent supervision in the provision of qualified care. Accordingly, clinical supervision was considered to be a significant benefit to both nurses and patients. Bush (2005) argued that the art of a supervisor lies in inspiring and facilitating critical reflective practice in the individual being supervised. In this regard, attention should be paid to the emotional needs of the individual under supervision, how he or she has been affected by experiences, and how to deal with those experiences constructively (Bush, 2005). Brunero and Stein-Parbury (2008) conducted a study and indicated that systematic clinical supervision may be a way to show and use the knowledge that is embedded in practice and to improve the efficiency, climate, and cooperation within work groups (Brunero & Stein-Parbury, 2008). Likewise, Arian, Mortazavi, TabatabaeiChehr, Tayebi, and Gazerani (2015) recommended effective planning and appropriate supervised encouragement to improve patient education programs. Furthermore, evidence indicates that many employees use only 20%–30% of their working capacity, which could be increased to 80%–90% if they were properly motivated by appropriate feedback (Toloei, Dehghan Nayeri, Faghihzadeh, & Sadughi Asl, 2006). In addition, Corder and Ronnie (2018) showed that increasing the motivation of nurses leads to better nursing care and that patient education is one aspect of professional care that requires relatively high levels of motivation.

Empowering the nursing profession was another subcategory that emerged from the data, with lack of power and authority in nursing personnel identified as one of the obstacles to patient education in hospitals. In this regard, Adib Hagbaghery, Salsali, and Ahmadi (2004) performed a qualitative research and stated that the power of nurses was influenced by “application of knowledge and skills,” “having authority,” “being self-confident,” “unification and solidarity,” “being supported,” and “organizational culture and structure.” They recommended that delegating authority to and enhancing the self-confidence of nurses could help them apply knowledge in practice. Moreover, fostering teamwork and mutual support among nurses may promote the development of their collective power and provide a basis for achieving better working conditions, professional independence, and self-regulation (Adib Hagbaghery et al., 2004). Similarly, Habibzadeh, Ahmadi, and Vanaki (2013) conducted a study on the challenges and facilitators of professionalization in nursing and reported that increasing the number of postgraduate nurses and improving work conditions for nurses would facilitate improvements in nursing.

In addition, this study identified popular beliefs as key to improving patient education. The participants stated the belief that good and sustainable change may be accomplished by systematizing every impetus. Stopped in this respect, Seyedin et al. (2015) concluded that establishing a multidisciplinary patient education committee and determining patient education coordinators would facilitate this process. They also said that a supportive administration was needed to accomplish patient education. In another study, 69% of nurses agreed that supervisors and managers emphasized the importance of patient education (Seyedin et al., 2015). Furthermore, Marcus (2014) stated that many other providers and practitioners, including social workers, rehabilitation therapists, home healthcare workers, educators, patient advocates, and librarians, play a crucial role in patient education and counseling and that each provider needs to work both individually and collaboratively. Finally, the literature has highlighted the importance of using action research models to improve collaboration (Dechairo-Marino, Jordan-Marsh, Traiger, & Saulo, 2001; Sabet Sarvestani et al., 2016).

One of the solutions stated clearly by our participants was the active enrollment of supervisors, physicians, and nursing and medical students into the patient education process. Review of the literature also revealed that a team of healthcare providers was required to teach patients about medications, postdischarge management, and when and how to seek postdischarge medical services. Unfortunately, the role of senior managers and their involvement in the patient education process have been neglected (Arian et al., 2015; Jafari et al., 2015).

The results of this study further indicate the necessity to redesign patient education forms. The participants recommended designing a form for patient education to be completed by nurses and physicians at patient bedsides and then evaluated by supervisors on a daily basis from admission to discharge. These forms will be maintained at patient bedsides and help healthcare professionals to easily determine what education has been provided and whether the patient adequately understands each component of this education. In this regard, Seyedin et al. (2015) suggested developing a standardized framework and an easily understood toolkit for the patient education program, which may improve the abilities of nurses to deliver effective patient education in hospitals (Seyedin et al., 2015). Likewise, Sabet Sarvestani, Moattari, Nasrabadi, Momennasab, and Yektatalab (2015) showed the effectiveness of using standard forms for nursing handover in the pediatric department.

Moreover, our findings indicated the importance of redesigning the accreditation process and nurse job description in hospitals. The accreditation process is a new, time-consuming project in hospitals that must be conducted carefully by qualified personnel. The participation of nurses in this process may prevent them from providing certain aspects of nursing care such as patient education. Therefore, because of new nursing duties, the accreditation process and nurses’ job description need to be revised. Chagheri, Amerion, Ebadi, and Safari (2014) disclosed that teaching accreditation standards to nurses was of utmost importance and that nursing motivation to participate in these classes needed to be improved. Enhancing the professionalism and practicality of these classes and using a system of clinical supervision and encouragement may improve the efficiency of these classes (Chagheri et al., 2014)

Providing a suitable environment and facilities was another of our findings. Oyetunde and Akinmeye (2015) explained that good-quality patient education requires the provision of appropriate resources in terms of time, facilities, and equipment. Allocating a place for teaching and being left alone without interruptions were also described as important in this regard. Moreover, Arian et al. (2015) conducted a study on the obstacles to patient education based on managers’ points of view and found lack of funds to be an important obstacle. Hence, they recommended providing adequate funding for training classes, hiring sufficient nurses, planning, and close monitoring. Moreover, Strömberg (2005) proved that new technologies such as computer-based education and telemonitoring may be used to improve patient education. In addition, Hadian and Sabet (2013) pointed to the importance of in-service education for improving nurses’ knowledge related to providing appropriate care.

Another subcategory that emerged was improving the quality of education. Marcus (2014) mentioned that communication was effective when patients received accurate, timely, complete, and unambiguous messages from providers, enabling them to practice their care responsibly. In fact, patients’ understanding of the information communicated by healthcare providers may enhance their satisfaction. On the other hand, providing verbal education to patients and their family members requires a multidisciplinary approach that considers learning style, literacy, and culture to apply clear communication and learning assessment methods. In one study, the combination of verbal and written training improved the quality of verbal patient and family education significantly (Marcus, 2014).

This study had some limitations that should be taken into account. First, the study was conducted in two hospitals. Thus, further studies should be conducted in other settings. Second, although the criteria for data saturation were met, certain issues or challenges may have been missed and not included in this study. Despite these limitations, the findings capture a good picture of the current situation and provide new insight into current patient education practices and a foundation for planning and implementing appropriate changes.

Conclusions

Qualitative analysis is an effective approach to understanding the perspective and recommendations of nurses with regard to improving patient education. Our analysis of multiple sources of data highlights the “master key” for patient education, which challenges managers to develop new strategies for improving patient education, which may then facilitate changes that increase the satisfaction levels of both nurses and patients. The result may lead to a higher level of patient safety together and a higher quality of care. Hence, in-service education in this field is highly recommended. Moreover, as the standardization of patient education depends entirely on the context, action research in the future should focus on addressing the challenges related to implementing effective patient education. This future research should include the individuals who are involved in the process as motivated stakeholders to help resolve the identified problems or challenges in a practical way.

Implications for Practice

As health literacy is primarily the responsibility of the health system, our results provide a “master key” to policy makers and managers of hospitals that will help them identify and remove the obstacles to effective patient education, especially in the context of rising healthcare costs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor of Fasa University of Medical Sciences for approving, supervising, and funding this research project (Grant number 95103).

Footnotes

Accepted for publication: November 27, 2017

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Cite this article as: Fereidouni, Z., Sabet Sarvestani, R., Hariri, G., Kuhpaye, S. A., Amirkhani, M., & Najafi Kalyani, M. (2019). Moving into action: The master key to patient education. The Journal of Nursing Research, 27(1), e6. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000280

References

- Adib Hagbaghery M., Salsali M., Ahmadi F. (2004). A qualitative study of Iranian nurses’ understanding and experiences of professional power. Human Resources for Health, 2(1), 9 10.1186/1478-4491-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghakhani N., Nia H. S., Ranjbar H., Rahbar N., Beheshti Z. (2012). Nurses’ attitude to patient education barriers in educational hospitals of Urmia University of Medical Sciences. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 17(1), 12–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arian M., Mortazavi H., TabatabaeiChehr M., Tayebi V., Gazerani A. (2015). The comparison between motivational factors and barriers to patient education based on the viewpoints of nurses and nurse managers. Journal of Nursing Education, 4(3), 66–77. (Original work published in Persian). [Google Scholar]

- Brunero S., Stein-Parbury J. (2008). The effectiveness of clinical supervision in nursing: An evidenced based literature review. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(3), 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bush T. (2005). Overcoming the barriers to effective clinical supervision. Nursing Times, 101(2), 38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagheri M., Amerion A., Ebadi A., Safari M. (2014). Nurses educational and motivational need for accreditation process in hospitals. Journal of Nurse and Physician in War, 2(5), 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Corder E., Ronnie L. (2018). The role of the psychological contract in the motivation of nurses. Leadership in Health Service, 31(1), 62–76. 10.1108/LHS-02-2017-0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechairo-Marino A. E., Jordan-Marsh M., Traiger G., Saulo M. (2001). Nurse/physician collaboration: Action research and the lessons learned. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 31(5), 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Systems Financing Health Systems and Services, World Health Organization. (2009). WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/choice/publications/d_economic_impact_guide.pdf

- Dorland. (2011). Dorland’s illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Farzianpour F., Hosseini S., Mortezagholi S., Mehrbany K. B. (2014). Accreditation of patient family education (PFE) in the teaching hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences from the nurses view. Pensee Journal, 76(6), 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fry H., Ketteridge S., Marshall S. (2009). A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U. H., Lundman B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habel M. (2002). Helping patient family take charge of their health. Patient Education, 31, 246–248. [Google Scholar]

- Habibzadeh H., Ahmadi F., Vanaki Z. (2013). Facilitators and barriers to the professionalization of nursing in Iran. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 1(1), 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hadian Z. S., Sabet R. S. (2013). The effect of endotracheal tube suctioning education of nurses on decreasing pain in premature neonates. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics, 23(3), 340–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari M., Olyari S. H., Zareian A., Dadgari F. (2015). Planning and implementation of patient education in CCU: A primary study. Journal of Political Care Science, 3(5), 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen V., Tossavainen K., Turunen H. (2013). Nurses’ roles in health promotion practice: An integrative review. Health Promotion International, 28(4), 490–501. 10.1093/heapro/das034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcum J., Ridenour M., Shaff G., Hammons M., Taylor M. (2002). A study of professional nurses’ perceptions of patient education. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 33(3), 112–118. 10.1080/21642850.2014.900450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. (2014). Strategies for improving the quality of verbal patient and family education: A review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 482–495. 10.1080/21642850.2014.900450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oermann M. H., Harris C. H., Dammeyer J. A. (2001). Teaching by the nurse: How important is it to patients? Applied Nursing Research, 14(1), 11–17. 10.1053/apnr.2001.9236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyetunde M. O., Akinmeye A. J. (2015). Factors influencing practice of patient education among nurses at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. Open Journal of Nursing, 5(5), Article ID 56519 10.4236/ojn.2015.55053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin S. H., Stalling K. D., London F. (2005). Patient education in health and illness. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Sabet Sarvestani R., Moattari M., Nasrabadi A. N., Momennasab M., Yektatalab S. (2015). Challenges of nursing handover: A qualitative study. Clinical Nursing Research, 24(3), 234–252. 10.1177/1054773813508134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabet Sarvestani R., Moattari M., Nasrabadi A. N., Momennasab M., Yektatalab S. H., Jafari A. (2016). Empowering nurses through action research for developing a new nursing handover program in a pediatric ward in Iran. Action Research, 15(2), 214–235. 10.1177/1476750316636667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scrutton J., Holley-Moore G., Bamford S.-M. (2015). Creating a sustainable 21st century healthcare system. Retrieved from http://www.ilcuk.org.uk/files/Creating_a_Sustainable_21st_Century_Healthcare_System.pdf

- Seyedin H., Goharinezhad S., Vatankhah S., Azmal M. (2015). Patient education process in teaching hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Medical Journal of Islamic Republic of Iran, 29, 220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Streubert Speziale H., Rinaldi Carpenter D. (2007). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Strömberg A. (2005). The crucial role of patient education in heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 7(3), 363–369. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toloei M., Dehghan Nayeri N., Faghihzadeh S., Sadughi Asl A. (2006). The nurses’ motivating factors in relation to patient training. Journal of Hayat, 12(2), 43–51. [Google Scholar]