Despite the availability of evidence‐based cessation approaches and guidelines, smoking rates remain high among individuals diagnosed with cancer. In this article, the past 10 years of research addressing barriers to providing tobacco cessation treatment is reviewed, with a focus on increasing adherence to standard tobacco treatment practices among oncology care providers.

Keywords: Tobacco, Cancer, Oncologists, Patients, Smoking cessation

Abstract

Background.

Smoking after a cancer diagnosis negatively impacts health outcomes; smoking cessation improves symptoms, side effects, and overall prognosis. The Public Health Service and major oncology organizations have established guidelines for tobacco use treatment among cancer patients, including clinician assessment of tobacco use at each visit. Oncology care clinicians (OCCs) play important roles in this process (noted as the 5As: Asking about tobacco use, Advising users to quit, Assessing willingness to quit, Assisting in quit attempts, and Arranging follow‐up contact). However, OCCs may not be using the “teachable moments” related to cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship to provide cessation interventions.

Materials and Methods.

In this scoping literature review of articles from 2006 to 2017, we discuss (1) frequency and quality of OCCs' tobacco use assessments with cancer patients and survivors; (2) barriers to providing tobacco treatment for cancer patients; and (3) the efficacy and future of provider‐level interventions to facilitate adherence to tobacco treatment guidelines.

Results.

OCCs are not adequately addressing smoking cessation with their patients. The reviewed studies indicate that although >75% assess tobacco use during an intake visit and >60% typically advise patients to quit, a substantially lower percentage recommend or arrange smoking cessation treatment or follow‐up after a quit attempt. Less than 30% of OCCs report adequate training in cessation interventions.

Conclusion.

Intervention trials focused on provider‐ and system‐level change are needed to promote integration of evidence‐based tobacco treatment into the oncology setting. Attention should be given to the barriers faced by OCCs when targeting interventions for the oncologic context.

Implications for Practice.

This article reviews the existing literature on the gap between best and current practices for tobacco use assessment and treatment in the oncologic context. It also identifies clinician‐ and system‐level barriers that should be addressed in order to lessen this gap and provides suggestions that could be applied across different oncology practice settings to connect patients with tobacco use treatments that may improve overall survival and quality of life.

摘要

背景。癌症诊断后吸烟会对健康结果产生负面影响;而戒烟可以改善病症、副作用和整体预后。公共卫生部门和主要的肿瘤学组织已经确立了有关癌症患者戒烟治疗的指南,包括每次访视时对烟草使用情况进行临床评估。在这一过程(又称为 5A:询问 (Asking) 烟草使用情况;建议 (Advising) 使用者戒烟;评估 (Assessing) 戒烟意愿;协助 (Advising) 戒烟尝试;以及安排 (Arranging) 随访联系)中,肿瘤学保健医生 (OCC) 发挥着重要作用。然而,OCC 未必会利用这些与癌症诊断、治疗和存活率相关的“受教时刻”来提供戒烟干预。

材料和方法。在本篇囊括 2006 年至 2017 年多篇文章的范围文献综述中,我们讨论了 (1) OCC 对癌症患者和幸存者烟草使用情况评估的频率和质量;(2) 为癌症患者提供戒烟治疗的屏障;以及 (3) 提供者层面的干预对促进遵循戒烟指南的有效性和未来前景。

结果。OCC 没有充分解决患者的戒烟问题。回顾研究表明,尽管 75% 以上的患者在最初访视期间评估了烟草使用情况,并且 60% 以上的结果通常建议患者戒烟,但是在尝试戒烟后,建议或安排戒烟治疗或随访的百分比明显降低。只有不到 30% 的 OCC 报告提供了适当的戒烟干预培训。

结论。需要针对提供者层面和系统层面的变化进行干预试验,以促进在肿瘤学环境中纳入基于证据的戒烟治疗。在针对肿瘤学背景进行干预时,应注意 OCC 所面临的屏障。

实践意义:本文回顾了有关肿瘤学环境中烟草使用情况评估及戒烟治疗的最佳实践与现行实践之间差距的现有文献。同时确定了为缩小这种差距,应该解决的临床医生层面和系统层面的屏障,并提供了适用于不同肿瘤学实践环境的建议,以便将患者与戒烟治疗相关联,从而改善整体存活率和生活质量。

Introduction

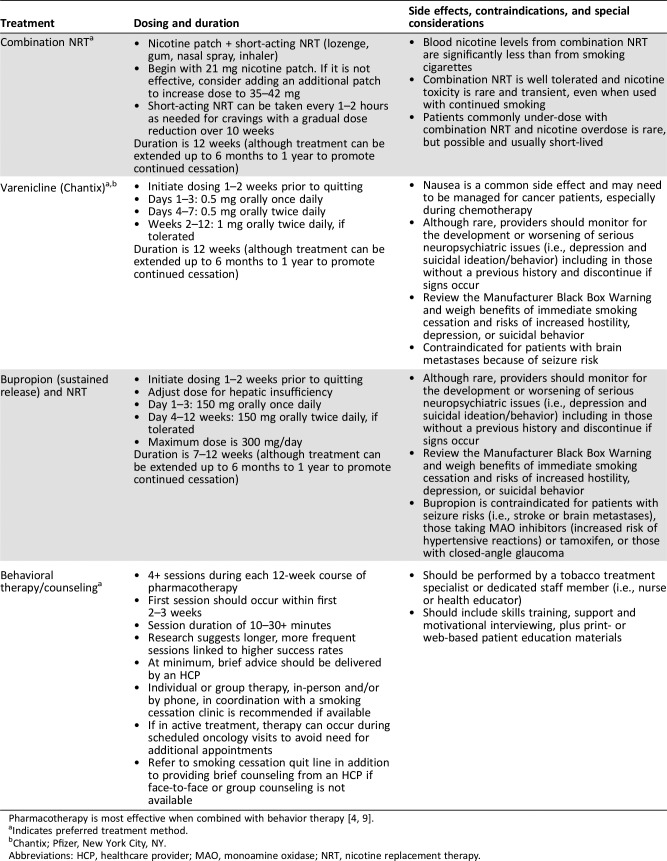

Smoking remains the most preventable cause of death worldwide. In the U.S. alone, tobacco use accounts for ∼480,000 premature deaths every year [1]. Cancer patients and survivors face even greater risk from smoking than the general population. The 2014 Surgeon General's report emphasized that continued smoking after a cancer diagnosis adversely influences health outcomes and overall survival, but quitting after diagnosis can improve cancer prognosis, overall health, and quality of life [2]. The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (TTUD) from the Public Health Service emphasize assessment and documentation of tobacco use in all clinical care encounters, along with referral to evidence‐based treatments (including pharmacotherapy, nicotine replacement, and behavioral treatments, most of which are safe and efficacious in cancer patients; Table 1). Oncology professional organizations, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Society of Clinical Oncology, have issued guidelines to emphasize the importance of smoking cessation and establish evidence‐based standards of tobacco use treatment (TUT) for cancer patients [3], [4].

Table 1. Smoking cessation therapy for cancer patients (adapted from National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines Version 2.2017).

Despite the guidelines and availability of evidence‐based cessation approaches, smoking rates remain high among individuals diagnosed with cancer [5], and cancer centers have been slow to establish tobacco treatment services. In their survey of 58 National Cancer Institute (NCI)‐designated cancer centers, Goldstein and colleagues found that only 58.6% reported TUT within their center (20.7% reported external TUT services and 20.7% had no TUT services) [6]. Only 38% of centers assessed tobacco as a vital sign and 48% had designated TUT personnel. Centers suboptimally implemented recommended clinician‐oriented TUT practices: only 35% noted adequate training of clinicians and 9% provided regular feedback to clinicians about their cessation referral rates. Based on these findings, the authors recommended that cancer centers should institutionally fund internal TUT programs and implement quality improvement efforts and that NCI should take a more active role in TUT provision [6]. The NCI has issued a call to action for all cancer centers to address smoking cessation for cancer patients and survivors [7] and recently offered supplemental funds from the Cancer Moonshot Initiative to facilitate implementation of evidence‐based TUT programs at NCI‐designated cancer centers [8].

The TTUD clinical practice guidelines note that all health care professionals, including oncology care clinicians (OCCs), should provide at least brief intervention to every tobacco user. Data from general health care settings show that advice from a clinician is influential; even 3 minutes of advice and smoking cessation counseling may increase the odds of abstinence by 30%–50%, and meta‐analyses show that advice from clinicians to stop smoking significantly increases quit rates [9], [10]. The ability to facilitate appropriate referrals and coordinate hand‐offs is also important; direct introduction to a TUT professional (so‐called “warm handoffs”) have been shown to increase enrollment in tobacco treatment programs over electronic referrals [11]. At each visit, clinicians should follow the 5As model of brief cessation intervention: (1) Ask all patients about their tobacco use; (2) Advise smokers to quit; (3) Assess smokers' willingness to quit; (4) Assist smokers with cessation; and (5) Arrange follow‐up contact to prevent relapse [9]. The 5As were formulated to be easily implemented across diverse clinical settings and patient populations and were designed with the understanding of busy clinic schedules [9]. For providers less comfortable with TUT delivery or with substantial time constraints, the 5As can be abbreviated to AAR: Ask, Advise, and Refer [9].

For patients receiving cancer care, an important step in successful TUT hinges on oncology care clinicians' consistent and effective use of the 5As or AAR. OCCs are trusted sources of information and guidance for cancer patients [12]. The combination of patients' advice‐seeking and increased motivation to quit make the oncologic context a powerful opportunity to engage in conversations about smoking cessation [13], [14]. A cancer diagnosis may serve as a “teachable moment” in which motivation for and interest in tobacco cessation increase [15]. The entire period from diagnosis through survivorship has been described as a “window of opportunity” through which clinicians can intervene and assist cancer patients in the tobacco cessation process [16]. Patients who continue to smoke after a cancer diagnosis often do not ask their OCCs for assistance because of stigma and guilt [17]. Therefore, clinicians play a critical role in initiating conversations about the risks of continued smoking after a cancer diagnosis, advising patients to quit, prescribing treatment, or providing referrals. Because relapse is common in this population, clinicians also play important roles in assisting patients in maintaining abstinence and preventing relapse [13].

Review Objectives

This scoping review covers oncology care clinicians' assessment and treatment of tobacco use among cancer patients and survivors through the framework of the 5As. We included papers that report data from multiple sources, including OCC self‐report, cancer patient/survivor report, clinic or health system representative report, and objective data sources such as electronic medical records or billing codes. For the purpose of this review, we defined OCC as any clinician who provides cancer treatment, follow‐up, or supportive care in the cancer trajectory. Based on more recent understanding of tobacco and cessation in the context of oncology and the release of the 2008 update to the “Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence” Clinical Practice Guideline, which established an expectation of standard tobacco treatment practices, we focused primarily on the last 10 years of research, addressing patient‐, clinician‐, and system‐level barriers to providing tobacco cessation advice and treatment to cancer patients, as well as interventions to increase clinician adherence to practice guidelines.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a scoping review in accordance with the methodological framework for scoping reviews published by Arksey and O'Malley [18] and advanced notably by Levac et al. [19], which includes guidance on identifying the research question, searching for and selecting relevant studies, charting the data, and summarizing the results.

Search Strategy

PubMed and PsycINFO electronic databases were initially searched in December 2016, with an updated search conducted on August 1, 2017, for potentially eligible studies published up to July 2017. The following key search words were used in different combinations: “teachable moment,” “providers,” “smoking cessation,” “oncology,” “tobacco,” “cancer,” and “5As” (e.g., [oncology OR cancer] and [smoking OR tobacco] and [provider OR clinician]). References were crosschecked, and all available abstracts were reviewed to obtain articles of interest. Articles were limited to human subjects, those written in English and published between 2006 and 2017.

Eligibility Criteria

To be included, studies were required to be empirical research focused on OCCs and to include data on at least one of following: (1) quality and/or frequency of conversations about tobacco use or cessation with adult cancer patients or survivors, (2) barriers in discussing tobacco use with cancer patients and survivors, and (3) interventions to increase the quality and/or frequency of tobacco treatment for cancer patients or survivors. Empirical studies of clinical practice guideline adherence included surveys and/or qualitative interviews completed by cancer patients, survivors, OCCs, cancer center administrators, and/or reviews of medical records. Letters, conference abstracts, editorials, opinion papers, and reviews that did not report on unique data were excluded. Based on U.S.‐specific guidelines, we only included papers reporting on data in the U.S. In the initial exploratory searches, we noted a limited number of studies explicitly assessing OCC adherence to all of the 5A components. To broaden the scope of the review, studies that assessed individual aspects or subsets of the 5As (e. g., tobacco use documentation, assessment, and counseling) and/or were not specifically described within the 5A or AAR frameworks were included (in the latter case, authors classified outcomes within the appropriate framework components). All authors were experienced in narrative, scoping, and systematic review methods. The first author (S.P.) conducted the literature search with support from the full team (J.S. and H.H). Abstracts of identified articles were reviewed against inclusion criteria (S.P.), and studies were excluded if eligibility criteria were not clearly met. If a paper could not be excluded based on the abstract, the full article was reviewed. A spreadsheet was designed and used by S.P. to aid in data extraction and charting. Coauthors (J.S. and H.H.) then reviewed the results of the article selection and data extraction process, and results were discussed as a team to describe emergent themes in the literature and to resolve any disagreements. Data collected from each article included authors and author affiliations, title, journal, year of publication, study setting, eligibility criteria, participants (patient/OCCs/administrators), sample size, reference to OCC assessment and treatment of tobacco use among cancer patients in routine practice settings, barriers to tobacco assessment and treatment, and any outcomes from interventions designed to improve OCC provision of TUT.

Results

Literature Search Results

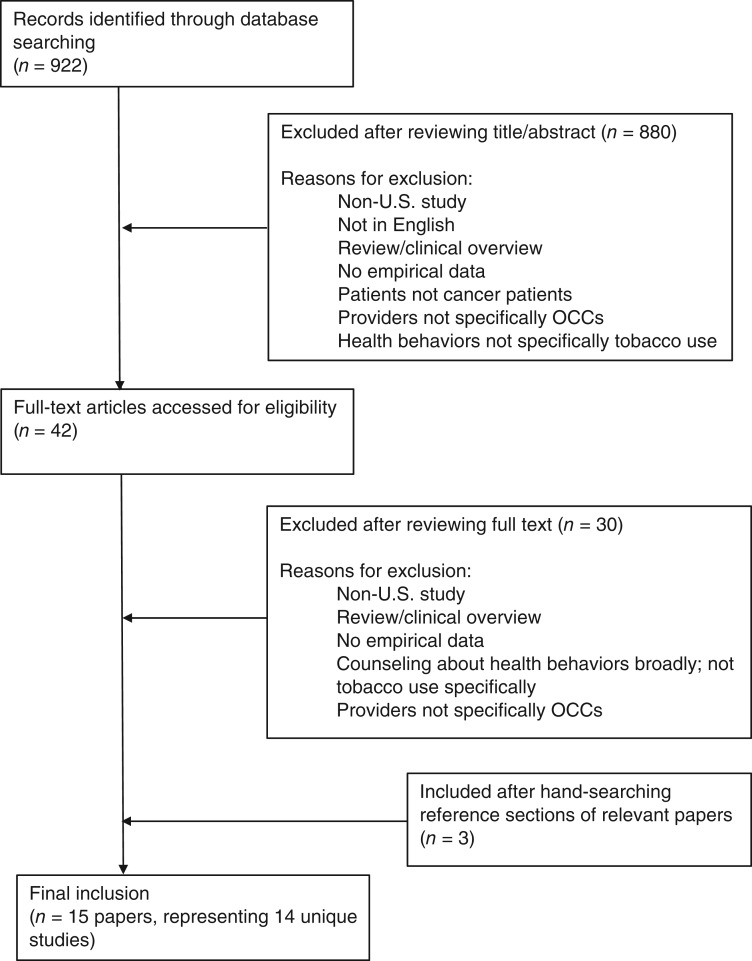

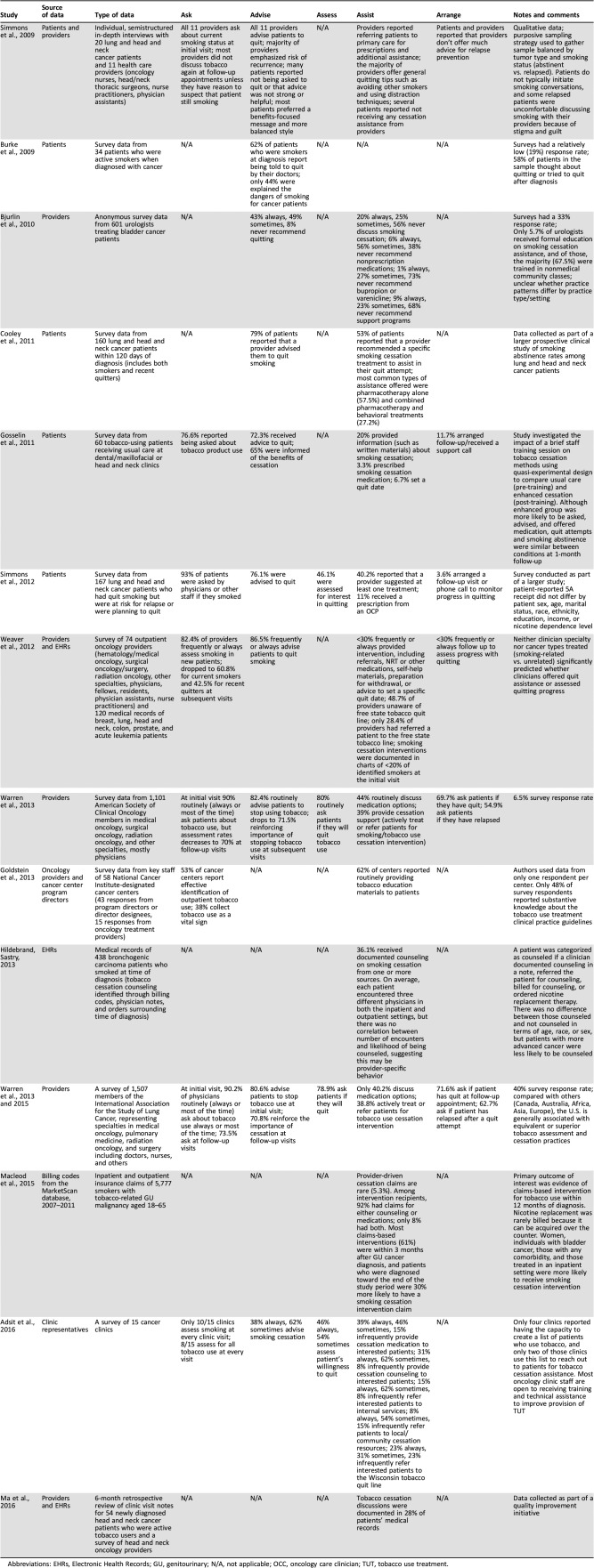

The initial search yielded 922 articles, based on review of abstracts; 42 full‐text articles were then accessed for eligibility, yielding 12 eligible articles. Three additional papers that were all eligible were identified after hand‐searching the reference sections of relevant papers (Fig. 1). In total, 15 papers were included in this scoping review, but 2 papers (by Warren and colleagues, 2013 and 2015) reported on the same survey data, resulting in 14 unique studies (Table 2). Although the 5As or AAR were mentioned in the majority of the studies reviewed, only one (by Simmons and colleagues) explicitly labeled each A. Therefore, the remaining studies required some amount of translation into the 5A/AAR framework (e.g., deciding that prescribing tobacco cessation medication falls under “Assist,” despite the fact that the authors of the original studies did not describe it that way explicitly). Of the 14 unique studies, 3 focused on all 5As, 7 focused on a subset of the 5As, and 4 addressed only a single A or discussed adherence to clinical practice guidelines broadly, with terms such as “providers discussed tobacco cessation” or “patients were counseled on smoking cessation.”

Figure 1.

Search process.

Abbreviation: OCCs, oncology care clinicians.

Table 2. Provider documentation, assessment, and treatment of tobacco use in cancer patients.

Abbreviations: EHRs, Electronic Health Records; GU, genitourinary; N/A, not applicable; OCC, oncology care clinician; TUT, tobacco use treatment.

Seven papers discussed barriers to 5A adherence. The papers used different approaches to examine clinician adherence to clinical practice guidelines, with seven studies using clinician report, five patient report, four Electronic Health Record (EHR) or billing codes, and two using report from clinic representatives or administrators. Eight of the fourteen studies collected data at academic medical centers, one study collected data from a community medical center, and five collected national/regional data from a variety of urban and rural practice settings, including private practice, academic institutions, managed care, and multispecialty groups. The majority of included studies (eight) focused specifically on OCCs treating tobacco‐related cancers such as lung, head and neck, and genitourinary, whereas the rest studied the behavior of OCCs treating patients with a variety of tumor types, including those related and unrelated to tobacco use.

Frequency of the 5As in Oncology Settings

Ask All Patients About Their Tobacco Use.

Oncology Care Clinicians were most likely to adhere to the first A, “ask all patients about tobacco use.” Across the seven relevant studies, 77%–100% of OCCs routinely asked about tobacco use at a patient's initial visit [13], [20]. However, in the three studies that addressed follow‐up, tobacco assessment rates dropped at subsequent visits [13], [21], [22], [23]. For example, Weaver and colleagues found that OCC‐reported rates of smoking assessment dropped from 82.4% to 60.8% (for current smokers) and 42.5% (for recent quitters) at follow‐up visits [22]. EHR review confirmed provider report in this study, with smoking status documentation rates ranging from 60% to 95% at patients' initial visit and dropping to 5%–80% at subsequent visits [22]. Low rates of tobacco assessment and documentation may be due in part to lack of system‐level infrastructure. For example, in their survey of 15 Wisconsin cancer clinics, Adsit and colleagues found that only 10 clinics collect smoking status and 8 assess for all tobacco use at every visit [25].

Advise Smokers to Quit.

Among 10 reviewed studies that focused on this aspect, results indicated that 62%–100% of OCCs sometimes or always encourage current smokers to quit [20], [28]. Delivery of this advice was variable and not always detailed or evidence‐based [9]. For example, in a survey of cancer patients smoking at diagnosis, 62% were advised to quit by an OCC, but only 44% reported being informed of the specific dangers of continued smoking during treatment [26]. Semistructured interviews noted that although providers feel confident in delivering their message to quit smoking, patients do not perceive their clinicians' messages as particularly strong or helpful. When asked about the effectiveness of clinician messaging, patients reported that they would prefer a more balanced approach that emphasized the benefits of cessation in addition to the harms of continued smoking [13].

Assess Smokers' Willingness to Quit.

Among the reviewed studies, only four documented adherence to “assessing” willingness to quit. In these studies, OCCs’ rates of routinely assessing willingness to quit ranged from 46% to 80% [20], [21], [23], [25].

Assist Smokers with Cessation.

Across nine of the reviewed studies, 20%–62% of OCCs routinely assist patients with tobacco cessation (e.g., discussing tobacco cessation or suggesting at least one treatment) [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [27], [28], [29]. Rates of actively treating (prescribing medication or referring to appropriate treatment) are consistently low (generally <40%) based on patient and provider report, billing codes, and EHR documentation [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [30], [31]. For example, in an analysis of billing claims from over 34 million enrollees with newly diagnosed genitourinary cancers and noted tobacco use disorder, only 5.3% had claims for smoking cessation interventions [30]. When treatment was discussed, varenicline or bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy were recommended more frequently than psychological treatments in all but two reviewed studies [20], [22], [25], [27], [28], [30].

Arrange Follow‐Up Contact to Prevent Relapse.

Six studies examined OCC follow‐up contact to prevent relapse, with rates ranging widely across reports (3.6%–72%) [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Studies examining whether OCCs arranged a follow‐up call or visit specifically to assess quitting progress showed lower rates compared with studies that simply documented whether OCCs ask about smoking at subsequent appointments (3.6%–11.7% vs. 55%–71%) [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Oncology care clinicians were more likely to ask smokers if they have quit at a follow‐up appointment than to ask a previously abstinent smoker if they have relapsed (70%–72% vs. 55%–62.7%) [21], [23].

Barriers to Providing Tobacco Assessment and Treatment

Clinician‐Level Factors.

Despite generally favorable attitudes toward TUT for cancer patients, more than half of OCCs in four different studies reported lacking training and confidence to provide cessation assistance [21], [22], [23], [27], [32]. Experience was a predictor of practice patterns: Urologists with smoking cessation training and those who treated higher numbers of cancer patients were more likely to consistently provide assistance [27]. Smoking‐related discussions were also considered lower priority, with assumptions that primary care clinicians had addressed it or that smoking cessation was not a specialist's responsibility [13], [22], [27]. Intent and experience were not sufficient in all domains; barriers to 5A adherence (especially Assist and Arrange) existed even among motivated practitioners who strongly agreed that smoking cessation was important to health outcomes [21]. Across a range of studies, the most frequently identified reasons for not providing assistance included the perception that patients lacked motivation or interest in quitting, that patients were already overwhelmed, or that patients were unwilling to stop [21], [22], [23], [31], [32]. Some providers were also concerned about patient resistance to treatment or feared that speaking about smoking would damage rapport [21], [22], [23], [32].

System‐Level Factors.

Across five separate studies, one third to one half of OCCs cited system‐level factors, including lack of time and resources, as barriers to providing TUT [21], [22], [23], [27], [31], [32]. Some OCCs were also unsure where to refer patients or were unaware of community resources such as free quitlines [22], [23], [25]. In their quality improvement initiative, Ma and colleagues discovered only 13% of OCCs were aware of tobacco cessation resources prior to intervention [31]. Warren and colleagues also found that practice setting predicted provision of tobacco treatment. Compared with academic/university settings, clinicians practicing in nonacademic/hospital‐based environments were significantly less likely to ask patients about tobacco use or advise them to quit [32].

In a survey of NCI‐designated cancer centers, those with an “in‐house” TUT program had better communication between providers, and point‐persons emerged at these centers who made TUT a major part of their professional role [6]. Cancer center representatives surveyed about factors that would improve TUT most commonly endorsed stable funding, tobacco treatment specialists, space, training for staff, technical assistance for system enhancements, support from physicians, links to resources, and support from administration [6].

Interventions to Improve Adherence to 5As in Oncology Settings

Although delivery of the 5As in the oncologic context is a clearly identified concern, only two included studies examined interventions for OCCs to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines. A recent project demonstrated the effectiveness of a brief educational intervention, which included a 10‐minute TUT presentation for providers, distribution of a tobacco cessation “teaching sheet” with cancer‐specific reasons to quit smoking and a list of available community resources, placement of reminder signs in clinic rooms to alert OCCs to counsel patients about smoking cessation, and the introduction of an EHR template to facilitate tobacco use documentation and discussion at every visit [31]. Prior to the intervention, tobacco use status was recorded only during initial visits, but the process was modified so that it was assessed during vital sign collection at every visit. Five months after intervention, tobacco use discussion documentation increased from 28% to 56%, all head and neck OCCs could name at least one TUT resource in the community, and 88% of OCCs noted that the intervention prompted them to discuss tobacco cessation with their patients [31]. Gosselin and colleagues also tested the effect of a 1‐hour education session for OCCs treating head and neck cancer patients and found that the intervention significantly increased the number of patients who were asked about their smoking status, prescribed cessation medications, and received cessation support calls [24].

Limitations

The results of this review must be considered in the context of its potential limitations. These include the use of one initial rater instead of multiple data extractors and lack of consultation with a medical librarian [18]. Although all study authors were experienced in conducting rigorous reviews and were actively involved in the search process, these potential limitations should be considered in the context of emerging guidelines on conduct of scoping reviews [33].

Discussion

This review addresses the persistence of suboptimal tobacco assessment, referral, and treatment patterns in the oncology setting. It also highlights the need to address barriers, clarify roles within multidisciplinary cancer care teams, and develop scalable interventions to improve and sustain adherence to clinical practice guidelines, including the 5As/AAR.

The reviewed studies indicate that OCCs routinely implement the first two As (ask and advise) at patients' initial visit, but that the last three As (assess, assist, arrange) are delivered at much lower rates (<50%). Lack of training was identified as a primary barrier to referring and offering evidence‐based tobacco treatments. Although tobacco use intervention has been increasingly integrated into medical school curriculums, practicing OCCs may also require additional instruction [20]. It is important to note that stigma and nihilism may play an insidious role in the quality and frequency of TUT delivery [34]. Therefore, efforts to train OCCs should emphasize compassionate, evidence‐based 5A delivery, including Motivational Interviewing principles [35], [36]. The AAR model may be a better alternative to the 5As for OCCs who do not have training in direct cessation interventions. Educational efforts should extend beyond physician training alone; guidelines recommend that all clinicians who have contact with patients implement the 5A model, extending the clinical responsibility for TUT to the entire team of individuals providing cancer care. Being advised to quit by more than one type of health professional increases cessation attempts and readiness to quit [37]. Because nicotine dependence is by nature a relapsing, chronic disease requiring repeated intervention, persistence is critical and a coordinated effort is necessary [9].

System‐level changes are also needed, and any system‐level efforts will require active participation by clinicians, insurers, and institutions. One important area of focus includes comparing different models for delivering TUT in oncology settings to elucidate preferred roles and opportunities for engagement (e.g., comparing in‐house with external referrals or warm handoffs with automatic referrals). More research is also needed to better understand and address differences in adherence to TUT guidelines based on practice setting. Although promising strategies (e.g., dedicating a specialist or “champion” to provide TUT, standardizing systems to identify tobacco users) have been employed at several model cancer centers, the literature has not yet identified one program format that is superior, and different models may be necessary for various cancer care settings. Future research should compare or combine lessons learned from these implementation efforts and include evaluation measures such as cessation outcomes, service uptake, and cost‐per‐patient [9], [38]. Although NCI's Cancer Moonshot‐driven effort to facilitate integration of tobacco treatment into oncology settings at NCI‐designated cancer centers is primarily a service implementation initiative, this effort may generate program evaluation data that could provide a broader roadmap for service integration.

Conclusion

Recent interventions have reduced burden on the provider in delivering TUT, including the use of prompts within EHRs and automated referrals and follow‐up [39], [40], [41]. For example, one site integrated standardized tobacco assessment questions into the EHR to ensure patients were asked at each visit and automatic referrals to a dedicated tobacco cessation program were generated for current users and recent quitters [41]. Physicians had a minimal role in this process but were notified if patients required a prescription for a tobacco cessation medication. Automated support services such as interactive voice response telephone calls provide additional assessment and follow‐up points at a low cost and can generate opportunities for referral beyond the confines of the clinic visit.

Clinical reminders and decision support systems within the EHR can also reduce clinician burden in providing TUT. These systems have been implemented in a variety of settings to improve adherence to TUT guidelines and are cost‐effective, sustainable, feasible, and acceptable [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. Computerized clinical reminders increase the likelihood of documentation, engagement in counseling, and medication prescriptions, and they require minimal training to implement [47]. However, these electronic interventions have limitations, such as clinician pop‐up fatigue, and they may need to include embedded strategies to increase clinicians' motivation for use, such as generation of feedback reports [48]. Mobile health technology and targeting of household members and social support systems may also extend the impact of traditional behavioral support and pharmacotherapy cessation strategies. Although these strategies can reduce clinician burden, providers are a trusted source of advice and support during treatment and their role in TUT will remain important.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the University of Arizona Fellows Program.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Sarah N. Price, Heidi A. Hamann

Collection and/or assembly of data: Sarah N. Price

Data analysis and interpretation: Sarah N. Price, Jamie L. Studts, Heidi A. Hamann

Manuscript writing: Sarah N. Price, Jamie L. Studts, Heidi A. Hamann

Final approval of manuscript: Sarah N. Price, Jamie L. Studts, Heidi A. Hamann

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Cancer Facts Fig 2016. 2016:1‐9. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields PG, Herbst RS, Arenberg D et al. Smoking Cessation, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016;14:1430–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna N, Mulshine J, Wollins DS et al. Tobacco cessation and control a decade later: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3147–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burris JL, Studts JL, DeRosa AP et al. Systematic review of tobacco use after lung or head/neck cancer diagnosis: Results and recommendations for future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:1450–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein AO, Ripley‐Moffitt CE, Pathman DE et al. Tobacco use treatment at the U.S. National Cancer Institute's designated cancer centers. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan G, Schnoll RA, Alfano CM et al. National Cancer Institute conference on treating tobacco dependence at cancer centers. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:178–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NCI Cancer Moonshot Initiative . Administrative Supplements for P30 Cancer Center Support Grant to develop tobacco cessation treatment capacity and infrastructure for cancer patients. https://www.cancer.gov/research/key-initiatives/moonshot-cancer-initiative/funding.

- 9.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:158–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N et al. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;31:CD000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter KP, Faseru B, Shireman TI et al. Warm handoff versus fax referral for linking hospitalized smokers to quitlines. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: The significance of physicians' communication behavior. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:791–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Patel RD et al. Patient‐provider communication and perspectives on smoking cessation and relapse in the oncology setting. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahuja R, Weibel SB, Leone FT. Lung cancer: The oncologist's role in smoking cessation. Semin Oncol 2003;30:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westmaas JL, Newton CC, Stevens VL et al. Does a recent cancer diagnosis predict smoking cessation? An analysis from a large prospective US cohort. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ et al. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: Smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer 2006;106:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: Qualitative study. BMJ 2004;328:1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Unrod M et al. Oncology healthcare providers' implementation of the 5A's model of brief intervention for smoking cessation: Patients' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns 2012;86:414‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM et al. Practice patterns and perceptions of thoracic oncology providers on tobacco use and cessation in cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weaver KE, Danhauer SC, Tooze JA et al. Smoking cessation counseling beliefs and behaviors of outpatient oncology providers. The Oncologist 2012;17:455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM et al. Addressing tobacco use in patients with cancer: A survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosselin MH, Mahoney MC, Cummings KM et al. Evaluation of an intervention to enhance the delivery of smoking cessation services to patients with cancer. J Cancer Educ 2011;26:577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adsit R, Wisinski K, Mattison R et al. A survey of baseline tobacco cessation clinical practices and receptivity to academic detailing. WMJ 2016;115:143–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke L, Miller LA, Saad A et al. Smoking behaviors among cancer survivors: An observational clinical study. J Oncol Pract 2009;5:6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjurlin MA, Goble SM, Hollowell CM. Smoking cessation assistance for patients with bladder cancer: A national survey of American urologists. J Urol 2010;184:1901–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooley ME, Emmons KM, Haddad R et al. Patient‐reported receipt of and interest in smoking‐cessation interventions after a diagnosis of cancer. Cancer 2011;117:2961–2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hildebrand JR, Sastry S. “Stop smoking!” Do we say it enough? J Oncol Pract 2013;9:230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macleod LC, Dai JC, Holt SK et al. Underuse and underreporting of smoking cessation for smokers with a new urologic cancer diagnosis. Urol Oncol 2015;33:504.e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma L, Donohue C, DeNofrio T et al. Optimizing tobacco cessation resource awareness among patients and providers. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e77–e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren GW, Dibaj S, Hutson A et al. Identifying targeted strategies to improve smoking cessation support for cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1532–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamann HA, Ver Hoeve ES, Carter‐Harris L et al. Multilevel opportunities to address lung cancer stigma across the cancer control continuum. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1062–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y et al. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;1:CD006936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An LC, Foldes SS, Alesci NL et al. The impact of smoking‐cessation intervention by multiple health professionals. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gritz ER, Toll BA, Warren GW. Tobacco use in the oncology setting: Advancing clinical practice and research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE et al. Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults. JAMA 2014;312:719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nahhas GJ, Wilson D, Talbot V et al. Feasibility of implementing a hospital‐based “opt‐out” tobacco‐cessation service. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:937–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM et al. Automated tobacco assessment and cessation support for cancer patients. Cancer 2014;120:562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenssen BP, Shelov ED, Bonafide CP et al. Clinical decision support tool for parental tobacco treatment in hospitalized children. Appl Clin Inform 2016;7:399–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenssen BP, Bryant‐Stephens T, Leone FT, et al. Clinical decision support tool for parental tobacco treatment in primary care. Pediatrics 2016;137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahabee‐Gittens EM, Dexheimer JW, Gordon JS. Development of a tobacco cessation clinical decision support system for pediatric emergency nurses. Comput Inform Nurs 2016;34:560–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahabee‐Gittens EM, Dexheimer JW, Khoury JC et al. Development and testing of a computerized decision support system to facilitate brief tobacco cessation treatment in the pediatric emergency department: Proposal and protocol. JMIR Res Protoc 2016;5:e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein SL, Rosner J, DeWitt M et al. Design and implementation of decision support for tobacco dependence treatment in an inpatient electronic medical record: A randomized trial. Transl Behav Med 2017;7:185–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bae J, Ford EW, Huerta TR. The electronic medical record's role in support of smoking cessation activities. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1019–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bentz C, Bayley B, Bonin K et al. Provider feedback to improve 5A's tobacco cessation in primary care: A cluster randomized clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2007;9:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]