Abstract

Background

Aspirin is established as an effective prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism (VTE) after THA; however, there is no consensus as to whether low- or regular-dose aspirin is more effective at preventing VTE.

Questions/purposes

(1) Is there a difference in the incidence of symptomatic VTE within 90 days of elective THA using low-dose aspirin compared with regular-dose aspirin? (2) Is there a difference in the risk of significant bleeding (gastrointestinal and wound bleeding) and mortality between low- and standard-dose aspirin within 90 days after surgery?

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated 7488 patients in our database who underwent THA between September 2012 and December 2016. A total of 3936 (53%) patients received aspirin alone for VTE prophylaxis after THA. During the study period, aspirin was prescribed as a monotherapy for VTE prophylaxis after surgery in low-risk patients (no history of VTE, recent orthopaedic surgery, hypercoagulable state, history of cardiac arrhythmia requiring anticoagulation, or receiving anticoagulation for any other medical conditions before surgery). Patients were excluded if aspirin use was contraindicated because of peptic ulcer disease, intolerance, or other reasons. Patients received aspirin twice daily (BID) for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery and were grouped into two cohorts: a low-dose (81 mg BID) aspirin group (n = 1033) and a standard-dose (325 mg BID) aspirin group (n = 2903). The primary endpoint was symptomatic VTE (deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and pulmonary embolism [PE]). Secondary endpoints included significant bleeding (gastrointestinal [GI] and wound) and mortality. Exploratory univariate analyses were used to compare confounders between the study groups. Multivariate regression was used to control for confounding variables (including age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, and surgeon) as we compared the study groups with respect to the proportion of patients who developed symptomatic VTE, bleeding (GI or wound), and mortality within 90 days of surgery.

Results

The 90-day incidence of symptomatic VTE was 1.0% in the 325-mg group and 0.6% in the 81-mg group (p = 0.35). Symptomatic DVT incidence was 0.8% in the 325-mg group and 0.5% in the 81-mg group (p = 0.49), and the incidence of symptomatic PE was 0.3% in the 325-mg group and 0.2% in the 81-mg group (p = 0.45). Furthermore, bleeding was observed in 0.8% of the 325-mg group and 0.5% of the 81-mg group (p = 0.75), and 90-day mortality was not different (0.1%) between the groups (p = 0.75). After accounting for confounders, regression analyses showed no difference between aspirin doses and the 90-day incidence of symptomatic VTE (odds ratio [OR], 0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29-2.85; p = 0.85) or symptomatic DVT (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.26-3.59; p = 0.95).

Conclusions

We found no difference in the incidence of symptomatic VTE after THA with low-dose compared with standard-dose aspirin. In the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary, low-dose aspirin appears to be a reasonable option for VTE prophylaxis in otherwise healthy patients undergoing elective THA.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common cause of hospital readmission after THA [23]. Continuous improvements in perioperative anesthesia protocols and early postoperative mobilization have led to a substantial reduction in VTE incidence (< 1%) recently [6, 14, 17, 31]. Although chemoprophylaxis has been shown to reduce the risk of VTEs after THA, the benefits of using chemoprophylactic agents to prevent VTEs must be weighed against an increased risk of adverse events such as bleeding and periprosthetic joint infection [7, 8, 14, 29].

Aspirin has a major effect in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities [3] as well as a relatively low risk of side effects compared with more aggressive options. For high-risk procedures such as THA, aspirin has been shown to be as effective as other anticoagulation agents since the first report by Salzman et al. [14, 24, 27]. Although the use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis after THA was described a few decades ago [15, 26, 27], aspirin was endorsed only recently as a prophylactic agent by the medical community [19]. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) in 2008 and 2011 and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) in 2012 have jointly recommended the use of 325 mg aspirin, twice daily for 6 weeks after surgery, alone for the prophylaxis of VTE after THA [9, 16]. Since then, many studies comparing the efficacy of aspirin with other anticoagulation agents have demonstrated aspirin was as effective as other agents for the prophylaxis of VTEs after lower extremity joint arthroplasty [1, 14]. One study showed that low-dose aspirin (81 mg) was similarly effective as high-dose aspirin (325 mg) for the prevention of cardiovascular events after carotid endarterectomy [30]. In addition, side effects of aspirin are reportedly dose-dependent, especially the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding [25]. Evidence to support the use of low-dose aspirin for VTE after THA is minimal with only a recent study reporting benefits to the use of low-dose aspirin when compared with high-dose aspirin for VTE prevention after THA and TKA [21].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to answer the following questions: (1) Is there a difference in the incidence of symptomatic VTE within 90 days of elective THA using low-dose aspirin compared with regular-dose aspirin? (2) Is low-dose aspirin associated with a lower risk of significant bleeding (GI and wound bleeding) and mortality compared with regular-dose aspirin after THA?

Materials and Methods

After institutional review board approval, we retrospective reviewed 7488 patients who underwent THA between September 2012 and December 2016. A total of 3936 (53%) patients received aspirin alone for VTE prophylaxis after THA. During the study period, both aspirin regimens were considered as monotherapy in patients with no history of VTE, recent orthopaedic surgery, hypercoagulable state, a history of cardiac arrhythmia requiring anticoagulation, or receiving anticoagulation for any other medical conditions before surgery. Patients were excluded if aspirin use was contraindicated because of peptic ulcer disease, intolerance, or other reasons.

Of those treated with aspirin, a total of 1033 (26%) patients received aspirin (81 mg twice daily) for 4 to 6 weeks, and a total of 2903 (74%) patients received aspirin (325 mg twice daily) for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. Aspirin was initiated on the evening of or the next day after the procedure. All patients received multimodal VTE prophylaxis using pneumatic compression stockings after the procedure and physical therapy was initiated on the day of surgery or on postoperative Day 1 and continued daily throughout the hospital stay as part of the institution’s protocol for VTE prophylaxis. When examining the criteria for choosing low-dose versus regular-dose aspirin, surgeons’ census was that patients with fewer morbidities received low-dose aspirin and those with more comorbidities received regular-dose aspirin. Generally, the choice between low-dose versus standard-dose aspirin was based on the surgeon’s past training and experience and the number of comorbidities the patient has at the time of surgery.

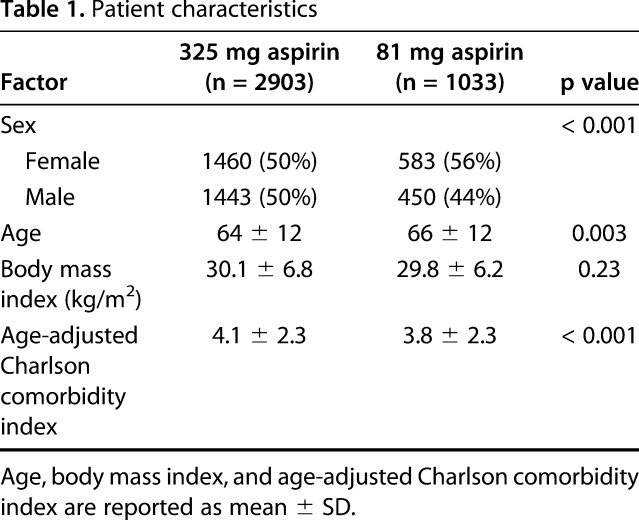

Patient demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and operative details were collected from the electronic medical records. Patient characteristics were different between the 325-mg aspirin group and the 81-mg aspirin group (Table 1). Patients who received 325 mg aspirin were slightly younger and had a higher comorbidity index score than those who received 81 mg aspirin, but were not significantly different in terms of body mass index (BMI). In addition, the 325-mg aspirin group had a lower proportion of female patients than the 81-mg aspirin group.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Outcome Assessment

Complications occurring within 90 days postoperatively were screened through a review of electronic medical records, including emergency department visits, unscheduled clinic visits, and readmissions. Complications recorded included symptomatic VTE including both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus (PE), bleeding (GI and wound), and mortality within 90 days after surgery. Symptomatic DVT and PE were recorded in patients who presented with signs and symptoms suspicious of DVT (leg swelling, erythema, calf pain, and tenderness) and confirmed by Doppler ultrasound for DVT and CT angiography or ventilation-perfusion studies for PE. Significant bleeding (any upper or lower GI or wound) was defined as bleeding if it required medical attention or required at least one unit of red blood cells or was associated with a drop of at least 1 g/dL of hemoglobin. Medical records were reviewed to identify the incidence of any outcome of interest treated at an outside institution and no patients were identified. In addition, record review for medication reconciliation at followup visits showed that patients were compliant with taking aspirin after surgery. The primary endpoint of the study was symptomatic VTE. The secondary endpoint included symptomatic PE, symptomatic DVT, bleeding (including GI and wound), and death within 90 days after surgery.

Risk of Bias

This study may have suffered a number of biases: (1) selection bias in which patients with fewer comorbidities may have received the lower dose of aspirin. Although all patients included in the study are considered at low risk for developing VTE after surgery, the choice between aspirin regimens relied on patients’ other comorbidities and surgeon preference. To adjust for this potential bias and extrapolate a meaningful difference in VTE incidence between the aspirin groups, a multivariate logistic regression model was used that adjusted for demographics and comorbidities as confounding factors and the surgeons as a random effect to eliminate potential selection bias. (2) Transfer bias in which the completeness and the length of followup to capture the events of interest could be a confounder. Patients were assessed for followup completeness through manual chart review. Patients were considered to be lost to followup if they had no clinical encounters after surgery. None of the patients included in the study had no followup after surgery. However, we identified 78 (1.9%) patients in the study population who had at least one visit up to 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, but no followup visits were available at 90 days after surgery. Of those, 20 patients (1.9%) were in 81-mg aspirin group and 58 patients (2.0%) were in the 325-mg aspirin group. (3) Assessment bias in which the question of whether the methods to identify the outcomes of interest were adequate. The outcomes of interest were identified through chart review of records for postoperative visits, emergency department visits, and hospital readmissions for clinical suspicion of VTE and their respective imaging confirmatory studies. However, patients may have been diagnosed at an outside institution. To account for possible occurrence of outcome of interest events at an outside institution, encounters with other healthcare providers after surgery were also screened for patient self-reported incidence of VTE within 90 days after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using the R statistical programming language (R Version 3.3.3, Vienna, Austria). All testing was two-sided and considered significant at the 5% level. For the primary endpoint of the study (symptomatic VTE), we utilized a 0.25-percentage point difference as the margin for the power calculation based on Parvizi et al. [21]. At 0.80 standard for power, the current study is adequately powered to test for a significant difference at a margin of 0.25% for the incidence of symptomatic VTE. It is important to note that the study was not powered to detect any differences in the incidence of symptomatic DVT, symptomatic PE, bleeding, or mortality between the groups.

For the “unadjusted” (univariate) comparisons, categorical variables were compared between groups using either Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Univariate (unadjusted) odds ratios for the outcomes of interest between the groups were recorded between the 81-mg aspirin group and the 325-mg aspirin group as a reference: symptomatic VTE (0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23-1.34; p = 0.18), symptomatic DVT (0.60; 95% CI, 0.23-1.61; p = 0.31), symptomatic PE (0.56; 95% CI, 0.12-2.57; p = 0.45), significant bleeding (0.70; 95% CI, 0.08-6.30; p = 0.75), and death (0.70; 95% CI, 0.08-6.30; p = 0.75). Continuous variables were compared between the groups using Welch’s two-sample t-test. A multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression model was considered for each response variable where each response was modeled as a function of aspirin dosage and the covariates. The covariates included in the regression model were age, sex, BMI, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), and surgeon. All covariates were treated as fixed effects except surgeon, which was treated as a random effect.

Results

After controlling for relevant confounding variables like age, sex, BMI, CCI, and surgeon, we found no difference between low- and standard-dose aspirin in terms of symptomatic VTE. The 90-day incidence of symptomatic VTE in the entire study population (both cohorts) was 0.9% (36 of 3936 patients). There was no difference (p = 0.30) in the incidence of VTE between groups: 0.6% (six of 1033 patients) in the 81-mg aspirin group compared with 1.0% (30 of 2903 patients) in the 325-mg aspirin group. There was no difference in the 90-day incidence of symptomatic DVT between the two groups. The incidence of symptomatic DVT in the 325-mg aspirin group was 0.8% (23 of 2903 patients) compared with 0.5% (five of 1033 patients) in the 81-mg aspirin group (p = 0.43). There was no difference in the 90-day incidence of symptomatic PE between the two groups. The incidence of PE in the 325-mg aspirin group was 0.3% (10 of 2903 patients) compared with 0.2% (two of 1033 patients) in the 81-mg aspirin group (p = 0.74).

There was no difference in the 90-day incidence of clinically significant bleeding after surgery between the two groups. The incidence of bleeding after surgery was 0.1% (four of 2903 patients) in the 325-mg aspirin group compared with 0.1% (one of 1033 patients) in the 81-mg aspirin group (p = 0.75). Three of the five patients had GI bleeding and two patients had wound-related bleeding. Of the 3936 study patients, four patients (0.1%) died within the first 90 days after surgery in the 325-mg aspirin group and one patient died in the 81-mg aspirin group (p = 0.75).

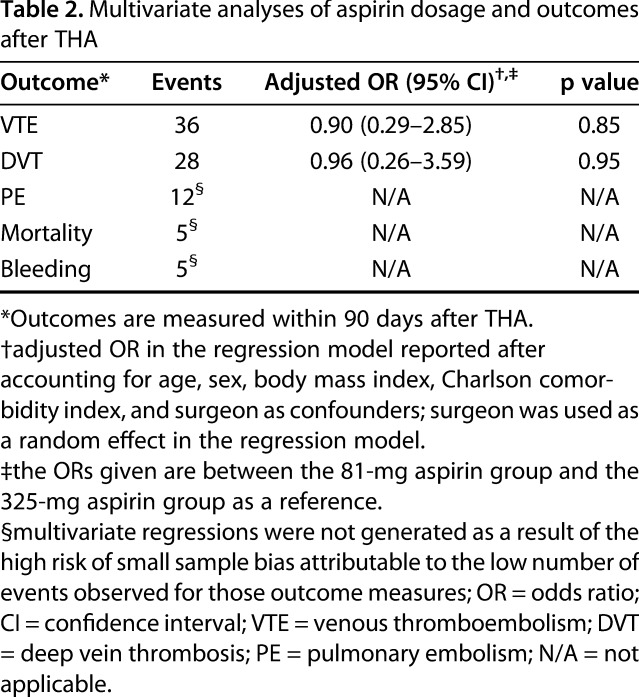

After accounting for age, sex, BMI, CCI, and surgeon, we found no difference between low- and standard-dose aspirin in terms of bleeding or death after THA. The regression model showed no difference between aspirin doses and the incidence of symptomatic VTE (odds ratio [OR], 0.90; 95% CI, 0.29-2.85; p = 0.85) or symptomatic DVT (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.26-3.59; p = 0.95) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses of aspirin dosage and outcomes after THA

Discussion

Aspirin has been effective for the prevention of VTEs after THA. However, the question of whether there is no difference in the incidence of VTE after THA with low- or regular-dose aspirin as the sole chemoprophylactic agent is still questionable. Although many studies have compared the efficacy of high-dose aspirin with other anticoagulation modalities [1, 18, 20, 22], only two studies have compared different doses of aspirin prescribed for the prevention of symptomatic VTEs after total joint arthroplasty [11, 21]. Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the incidence of symptomatic VTE within 90 days after elective THA between 81 mg aspirin twice a day and 325 mg aspirin twice a day and if low-dose aspirin was associated with a lower risk of significant bleeding and death compared with regular-dose aspirin after THA.

This retrospective study has several limitations. Although the study population included patients at low risk for VTE after surgery, there was no distinct criteria for the choice between the two aspirin regimens. With the absence of guidelines and recommendations recognizing clear indications for aspirin dosing regimens, the choice between doses was dependent on each surgeon’s own experience, training as well as the number of comorbidities associated with each patient. The study showed that patients who received low-dose aspirin had fewer comorbidities than those received the standard dose, although the difference in the CCI might not be clinically relevant. To adjust for this potential bias and extrapolate a meaningful difference in VTE incidence between the aspirin groups, a multivariate logistic regression model was used that adjusted for demographics and comorbidities as well as surgeons as a random effect to eliminate potential selection bias. Paucity of evidence linked operative details (approach, implant type, operative time) to the incidence of VTE after elective THA in low-risk patients; therefore, those variables were not included in the study.

Post hoc power analysis showed that the study was powered to detect a 0.25% difference in the incidence of symptomatic VTE between the two aspirin regimens. The study was significantly underpowered to detect differences in other important endpoints (PE or mortality) between the groups as a result of the rarity of those events, especially in low-risk patients after elective THA. The study design prevented us from establishing noninferiority, inferiority, or a superiority relationship between the aspirin doses. We can conclude, however, that low-dose aspirin can be a viable agent for the prevention of symptomatic VTE after elective THAs in healthy patients. We also did not assess other important outcomes such as the incidence of periprosthetic joint infection that has been previously reported [14, 21].

In addition, followup completeness was assessed. There was a small percentage of patients (1.9%) who did not have complete 90-day followup. Those patients had at least one visit up to 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, but no followup visits were available at 90 days after surgery. There was no differential loss to followup between the groups (1.9% for low- and 2.0% for standard-dose aspirin). Furthermore, the study main endpoint was to evaluate the difference in symptomatic VTEs, but not all VTEs between the groups because the screening for unsuspected VTE is no longer recommended if there is no change in the patient’s clinical status because routine postoperative screening for DVT after hip arthroplasty does not change outcomes or clinical management.

Moreover, the criteria used to identify significant bleeding events were not consistent with the standardized definitions of major surgical bleeding events proposed by the Scientific and Standardization Committee (SSC) of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis [28]. However, the study criteria offered a lower threshold to detecting bleeding events after surgery than the standard definition. Finally, because the difference in the effect of enteric-coated versus plain formulations of aspirin is still controversial, we did not attempt to compare between enteric-coated and plain formulations of both aspirin regimens [5, 12, 13].

This study concurs with multiple previous reports that have shown that aspirin is an effective treatment for the prevention of VTE after THA [2, 4, 14, 22]. However, in terms of aspirin dosing, the evidence base is more limited. The use of low-dose aspirin in the prevention of VTE after total joint arthroplasty has become under scrutiny recently. A number of studies investigated or are currently investigating the role of low-dose aspirin in the prevention of VTE. The PEPPER trial (Comparative Effectiveness of Pulmonary Embolism Prevention After Hip and Knee Replacement) is a randomized study comparing the three most commonly used anticoagulants in North America in patients who have elected to undergo primary or revision hip or knee arthroplasty. The anticoagulants being compared are enteric-coated aspirin (81 mg twice a day), low-intensity warfarin, and rivaroxaban. The primary outcomes include all-cause mortality plus PE and DVT within 6 months after surgery [22]. In addition, Parvizi et al. [21] examined the efficacy and adverse event profiles of low-dose (81 mg twice a day) versus regular-dose aspirin (325 mg twice a day) regimens for 4651 patients undergoing THA and TKA. They found that low-dose aspirin was not inferior to regular-dose aspirin in the prevention of VTE, which our study corroborates and supports. These findings were similar to the Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial that found a significant reduction in the incidence of PE in patients who received low-dose aspirin after surgical intervention for hip fracture as well as those who underwent elective primary THA [22]. It is important to note that the PEP trial addressed mainly patients with hip fracture. In some patients, other thromboprophylactic agents were used in addition to aspirin when deemed necessary; patients were followed up for 35 days after surgery; and most of the patients undergoing arthroplasty also receive heparin during their hospital stay.

The 90-day incidence of VTE reported in our study is considered low (0.9% [36 of 3936 patients]). Our study only evaluated the incidence of symptomatic VTE. Routine screening with Doppler ultrasound was not used in asymptomatic patients; thus, asymptomatic thrombotic events may not have been detected. The low incidence of VTE can be attributed, in addition to aspirin use, to other multimodal protocols used perioperatively to minimize the risk of VTE including pneumatic compression during the inpatient stay as well as early mobilization after the procedure. One study compared VTE incidence after THA between two aspirin doses and reported that the incidence of VTE was 0.3% in a high-dose aspirin group and 0.1% in a low-dose aspirin group [21]. Another study evaluated VTE rates in 30,270 patients receiving aspirin or warfarin after THA and TKA based on an individualized risk assessment for VTE. They reported a VTE incidence of 0.2% (10 of 4102) for aspirin and 1.8% (329 of 18,649) for warfarin in low-risk patients and 0.6% (five of 796) for aspirin and 3.2% (217 of 6723) for warfarin in high-risk patients [14].

The study also showed no difference in the incidence of GI or wound bleeding between the two aspirin doses administered. Although the risk of GI bleeding has been reported to be dose-dependent [25], the incidence of GI bleeding was very low in this study and we did not detect any significant difference between aspirin doses. Similarly, Parvizi et al. reported no difference in the incidence of GI bleeding after THA and TKA between the 81-mg aspirin group (0.3%) and the 325-mg aspirin group (0.4%) [21]. Feldstein et al. [11] compared the side effects of different regimens of aspirin in 643 patients after THA and TKA in a prospective study. They found that low-dose aspirin (81 mg twice a day for 4 weeks) was associated with less GI distress and nausea compared with high-dose aspirin (325 mg twice a day for 4 weeks). They also reported an overall GI bleeding risk of 0.9% with 0.7% (two of 282) in the 325-mg aspirin group and 1.1% (four of 361) in the 81-mg aspirin group. In addition, the study reported a 0.13% overall 90-day mortality rate after THA, which was similar to what has been reported by others [10, 21].

Our study, similar to Parvizi et al., investigated the incidence of symptomatic VTEs defined by clinical presentation and confirmatory imaging studies [21]; both utilized a 0.25% difference in the incidence of symptomatic VTE as a clinically significant difference. They also reported the incidence of periprosthetic joint infection in their population. On the other hand, we recognized significant bleeding (GI and wound) defined as bleeding that required at least one unit of red blood cells or was associated with drop of at least 1 g/dL of hemoglobin. Parvizi et al. reported GI bleeding only confirmed by endoscopy with no assessment of significance. Feldstein et al. reported subjective data from patient surveys conducted 30 days after surgery. The study was significantly underpowered to detect any difference in GI bleeding between the aspirin regimens [11].

In conclusion, there was no difference in the incidence of symptomatic VTE between low-dose aspirin and standard-dose aspirin within 90 days after elective THA. Low-dose aspirin can be considered an option for the prevention of symptomatic VTE. The next step is to explore the use of multimodal prophylaxis with and without chemoprophylactic agents in the prevention of VTE in low-risk patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Messner, senior statistician, Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he or she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, USA.

References

- 1.An VVG, Phan K, Levy YD, Bruce WJM. Aspirin as thromboprophylaxis in hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2608–2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson DR, Dunbar MJ, Bohm ER, Belzile E, Kahn SR, Zukor D, Fisher W, Gofton W, Gross P, Pelet S, Crowther M, MacDonald S, Kim P, Pleasance S, Davis N, Andreou P, Wells P, Kovacs M, Rodger MA, Ramsay T, Carrier M VP. Aspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med . 2016;4:800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T, Patrono C, Roncaglioni MC, Zanchetti A. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozic KJ, Vail TP, Pekow PS, Maselli JH, Lindenauer PK, Auerbach AD. Does aspirin have a role in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox D, Fitzgerald DJ. Lack of bioequivalence among low-dose, enteric-coated aspirin preparations. Clin Pharmacol Ther . 2018;103:1047–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLaValle AG, Serota A, Go G, Sorriaux G, Sculco TP, Sharrock NE, Salvati EA. Venous thromboembolism is rare with a multimodal prophylaxis protocol after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2006;443:146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eriksson BI, Borris LC, Friedman RJ, Haas S, Huisman MV, Kakkar AK, Bandel TJ, Beckmann H, Muehlhofer E, Misselwitz F, Geerts W; RECORD1 Study Group. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip arthroplasty. N Engl J Med . 2008;358:2765–2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Rosencher N, Kurth AA, van Dijk CN, Frostick SP, Prins MH, Hettiarachchi R, Hantel S, Schnee J, Büller HR; RE-NOVATE Study Group. Dabigatran etexilate versus enoxaparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip replacement: a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2007;370:949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S, Ortel TL, Pauker SG, Colwell CW. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e278S–e325S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faour M, Piuzzi NS, Brigati DP, Klika AK, Mont MA, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. Low-dose aspirin is safe and effective for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:S131–S135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldstein MJ, Low SL, Chen AF, Woodward LA, Hozack WJ. A Comparison of two dosing regimens of ASA following total hip and knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:S157–S161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein JL, Scheiman JM, Fort JG, Whellan DJ. Aspirin use in secondary cardiovascular protection and the development of aspirin-associated erosions and ulcers. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol . 2016;68:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haastrup PF, Grønlykke T, Jarbøl DE. Enteric coating can lead to reduced antiplatelet effect of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol . 2015;116:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang RC, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ, Chen AF, Austin MS. Aspirin is as effective as and safer than warfarin for patients at higher risk of venous thromboembolism undergoing total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennings JJ, Harris WH, Sarmiento A. A clinical evaluation of aspirin prophylaxis of thromboembolic disease after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 1976;58:926–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johanson NA, Lachiewicz PF, Lieberman JR, Lotke PA, Parvizi J, Pellegrini V, Stringer TA, Tornetta P, 3rd, Haralson RH, 3rd, Watters WC., 3rd American academy of orthopaedic surgeons clinical practice guideline on symptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2009;91:1756–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leali A, Fetto J, Moroz A. Prevention of thromboembolic disease after non-cemented hip arthroplasty. A multimodal approach. Acta Orthop Belg . 2002;68:128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lotke PA, Palevsky H, Keenan AM, Meranze S, Steinberg ME, Ecker ML, Kelley MA. Aspirin and warfarin for thromboembolic disease after total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 1996;324:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCardel BR, Lachiewicz PF, Jones K. Aspirin prophylaxis and surveillance of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pannucci C, MacDonald J, Ariyan S, Gutowski K, Kerrigan C, Kim J, Chung K. Benefits and risks of prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus in plastic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials and consensus conference. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2016;137:709–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parvizi J, Huang R, Restrepo C, Chen AF, Austin MS, Hozack WJ, Lonner JH. Low-dose aspirin is effective chemoprophylaxis against clinically important venous thromboembolism following total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2017;99:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1295–1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramkumar PN, Chu CT, Harris JD, Athiviraham A, Harrington MA, White DL, Berger DH, Naik AD, Li LT. Causes and rates of unplanned readmissions after elective primary total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) . 2015;44:397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raphael IJ, Tischler EH, Huang R, Rothman RH, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Aspirin: an alternative for pulmonary embolism prophylaxis after arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2014;472:482–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roderick PJ, Wilkes HC, Meade TW. The gastrointestinal toxicity of aspirin: an overview of randomised controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol . 1993;35:219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvati EA, Lachiewicz P. Thromboembolism following total hip-replacement arthroplasty. The efficicy of dextran-aspirin and dextran-warfarin in prophylaxis. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 1976;58:921–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salzman EW, Harris WH, DeSanctis RW. Reduction in venous thromboembolism by agents affecting platelet function. N Engl J Med . 1971;284:1287–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulman S, Angerås U, Bergqvist D, Eriksson B, Lassen MR, Fisher W; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost . 2010;8:202–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharrock NE, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Go G, Lyman S, Salvati EA. Potent anticoagulants are associated with a higher all-cause mortality rate after hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2008;466:714–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor DW, Barnett HJ, Haynes RB, Ferguson GG, Sackett DL, Thorpe KE, Simard D, Silver FL, Hachinski V, Clagett GP, Barnes R, Spence JD. Low-dose and high-dose acetylsalicylic acid for patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy: a randomised controlled trial. ASA and Carotid Endarterectomy (ACE) Trial Collaborators. Lancet. 1999;353:2179–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wille-Jørgensen P, Christensen SW, Bjerg-Nielsen A, Stadeager C, Kjaer L. Prevention of thromboembolism following elective hip surgery. The value of regional anesthesia and graded compression stockings. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 1989;247:163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]