ABSTRACT

Sarcopenia is an age-related condition associated with a progressive loss of muscle mass and strength. Insufficient protein intake is a risk factor for sarcopenia. Protein supplementation is suggested to improve muscle anabolism and function in younger and older adults. Dairy products are a good source of high-quality proteins. This review evaluates the effectiveness of dairy proteins on functions associated with sarcopenia in middle-aged and older adults. Randomized controlled trials were identified using PubMed, CINAHL/EBSCO, and Web of Science databases (last search: 10 May 2017) and were quality assessed. The results of appendicular muscle mass and muscle strength of handgrip and leg press were pooled using a random-effects model. The analysis of the Short Physical Performance Battery is presented in narrative form. Adverse events and tolerability of dairy protein supplementation were considered as secondary outcomes. Fourteen studies involving 1424 participants aged between 61 and 81 y met the inclusion criteria. Dairy protein significantly increased appendicular muscle mass (0.13 kg; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.26 kg; P = 0.04); however, it had no effect on improvement in handgrip (0.84 kg; 95% CI: −0.24, 1.93 kg; P = 0.13) or leg press (0.37 kg; 95% CI: −4.79, 5.53 kg; P = 0.89). The effect of dairy protein on the Short Physical Performance Battery was inconclusive. Nine studies reported the dairy protein to be well tolerated with no serious adverse events. Although future high-quality research is required to establish the optimal type of dairy protein, the present systematic review provides evidence of the beneficial effect of dairy protein as a potential nutrition strategy to improve appendicular muscle mass in middle-aged and older adults.

Keywords: sarcopenia, muscle mass, muscle strength, physical performance, dairy protein, systematic review, meta-analysis, middle-age and older adults

Introduction

Sarcopenia, the term used to define age-related progressive decline in muscle mass and muscle strength, was first reported by Rosenberg in 1989 (1). This condition can occur with or without a reduction in fat mass (1). There is not a specific age at which muscle mass and strength begin to diminish because of various contributing factors, including diet and physical activity levels. However, the sarcopenic process starts as early as the fourth or fifth decade of life (2). Sarcopenia is recognized as an increasing public health problem (3), with the number of people affected by sarcopenia worldwide projected to increase from >50 million in 2010 to >200 million in 2050 (4). Sarcopenia is associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes such as a poor quality of life, physical disability, depression, injurious falls, hospital admissions, and death (3). As a consequence, high health care expenditures of $900/person per year are attributed to sarcopenia (5).

The etiology of sarcopenia is multifactorial; it includes increased inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines), bed rest or low physical activity levels, hormonal disorders (6), and poor nutrition, particularly an inadequate energy and/or protein intake (4, 7). Nutrition is a modifiable risk factor for sarcopenia (8). For example, dietary protein enhances the anabolic activity in skeletal muscle and provides the necessary amino acids to stimulate postprandial muscle protein synthesis (9). Insufficient protein consumption has been associated with muscle mass depletion and poor physical function in older adults (8). A number of studies have been carried out to evaluate the potential effect of protein or amino acid supplementation on reducing the decline in functions associated with sarcopenia (i.e., muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance) in younger and older adults. In a meta-analysis of 22 randomized controlled trials (10), protein supplementation after prolonged resistance training was shown to increase lean muscle mass by 0.69 kg (P < 0.00001) and leg press strength by 13.5 kg (P < 0.005) compared with a placebo group in both younger and older adults. The majority of the included trials supplemented with whey protein from dairy, alone or in combination with amino acids or another type of dairy protein. In a recent meta-analysis of 10 trials, Hidayat et al. (12) found a positive effect of milk-based protein supplementation and resistance training on fat-free mass (0.74 kg; 95% CI: 0.30, 1.17 kg) in older adults, suggesting a potential role of dairy protein in promoting muscle anabolism.

Dairy products are good sources of high-quality protein, primarily in the form of either whey or casein (11). They are affordable and readily available throughout the world (12). Dairy products, including milk-protein supplements, do not require cooking or require only minimal preparation compared with other protein-rich foods such as lean meat, poultry, fish, and eggs (12). This makes dairy sources a practical option for older adults to consume adequate protein (12). Further research is required to determine if dairy proteins could be used as a dietary strategy to reduce the health risks associated with sarcopenia by improving muscle mass and muscle function.

Although previous meta-analyses have evaluated the effect of protein supplementation on muscle mass and strength, the potential dietary role of dairy protein in improving the primary outcome parameters of sarcopenia has not been specifically investigated to our knowledge. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the impact of dairy protein intake on muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in middle-aged to older adults with or without existing sarcopenia.

Methods

The current systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (13).

Eligibility criteria

The selection of the studies was restricted to full-text articles and the English language. The relevant studies had to meet the following criteria:

Participants: Studies conducted in humans only. Middle-aged to older adults [middle age defined as between 45 and 65 y old (14)] with or without sarcopenia.

Types of study: Randomized controlled trials in which the recruited subjects were randomly assigned to ≥1 intervention group (IG) compared with a control group (CG).

Types of intervention: The IG received dairy protein supplementation (e.g., whey protein, milk-protein concentrate, casein) or a protein-based dairy product (e.g., ricotta cheese). The duration of the intervention was ≥12 wk. This period of time was decided on the basis of the available evidence that muscle hypertrophy occurs within 12 wk in response to dietary modifications and protein supplementations during resistance training (15, 16). Inclusion of resistance training as part of the study intervention was optional.

Types of outcome measures: Primary outcomes were changes in muscle strength (kilograms) of handgrip and leg press measured by hydraulic hand dynamometer and 1-repetition-maximum strength test, respectively, and changes in appendicular skeletal muscle mass (kilograms) measured by DXA. Physical performance was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score.

The SPPB is a standard measure of physical performance, it assesses the individual's balance, strength, gait, and endurance (4). The score is calculated by summing the scores of 3 equally weighted tests: balance, gait speed, and chair stand (4). Table 1 defines the cutoff points of SPPB score in older adults (17).

TABLE 1.

Cutoffs of SPPB scores in older adults1

| SPPB score | Performance level |

|---|---|

| 4–6 | Low |

| 7–9 | Intermediate |

| 10–12 | High |

1Data from reference 17. SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

These variables have been suggested as primary outcome domains to define sarcopenia by the European Work Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (4), with the proposed measuring tools confirmed to be reliable and valid. Adverse events and intervention adherence were reported as the secondary outcomes. Exclusion criteria are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Exclusion criteria

| Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|

| Study design | Observational studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews |

| Population | Animals; children; subjects diagnosed with liver disease, kidney disease, or cancer; allergic/intolerant to milk protein or lactose; taking medications that might interfere with the intervention; with low cognitive function; taking protein supplementation other than the intervention dairy protein of study of interest |

| Outcome | Postprandial protein synthesis, muscle protein synthesis, muscle fibers, muscle biopsy |

Search strategy

PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), CINAHL (EBSCO) (https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/cinahl-database), and Web of Science (https://clarivate.com/products/web-of-science/databases/) databas-es were used for electronic searches. References of the retrieved studies and existing meta-analyses were also hand-searched. The search covered the period up to 10 May 2017. There were no publication date or publication type restrictions in this review. Key terms included in the search engines were as follows—study design: #1 randomized controlled trial OR controlled trial OR clinical trial; population: #2 adult OR older adults OR middle-aged adults; exposure: #3 milk OR milk protein OR dairy protein OR whey OR whey protein OR whey protein supplementation OR casein OR protein supplementation; outcome: #4 muscle mass OR skeletal muscle mass OR appendicular muscle mass #5 muscle strength #6 physical performance OR physical function OR functionality #7 (#4 OR #5 OR #6) #8 (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #7).

Data extraction

The following data were extracted and tabulated: author(s), year of publication, country of publication, study design, duration of intervention, participants’ characteristics (e.g., sample size, baseline characteristics, inclusions), description of the study arms, measured outcomes, and values of the outcomes of interests pre- and postintervention.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias (18). It addresses 6 specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selection reporting. In this review, as suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (18), a quality scale to assess the overall risk of bias was not used. The use of quality scales to appraise the included randomized trials tends to combine the assessments of aspects of the quality reporting with those of trial conduct (19). Instead, the judgments of overall risk of bias are made explicit by separating the assessment of internal and external validity (19). The study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were primarily performed by NIH with oversight by 2 experienced researchers (AA and FM). Differences were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

RevMan software (Review Manager, version 5.3.5; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014; http://community.cochrane.org/tools/review-production-tools/revman-5/revman-5-download) was used to perform the meta-analysis. The mean change (meanfinal – meanbaseline) of handgrip strength and appendicular muscle mass (AMM) and mean outcome value (final value) of leg press strength were retrieved for analysis. When only the baseline and final SDs were reported, the change SD was computed using the Cochrane Handbook proposed equation (18), as follows:

|

(1) |

where the imputed correlation coefficient is 0.80. Effect sizes are presented as mean differences (95% CIs) for the continuous outcomes. The results were pooled using the inverse variance random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird). I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity between studies. The I2 indicates the percentage of the variability in effect estimates across studies due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (I2 >50%: substantial heterogeneity) (19). The fixed-effects model was used when no heterogeneity was identified. A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

To investigate whether the changes in primary outcomes were affected by the subjects’ characteristics and individual intervention, a subgroup analysis was conducted adjusting for subjects’ mean age, subjects’ health status, and amount of protein supplementation. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding a single study, in turn, to investigate its effect on the results of the meta-analysis.

Results

Literature search

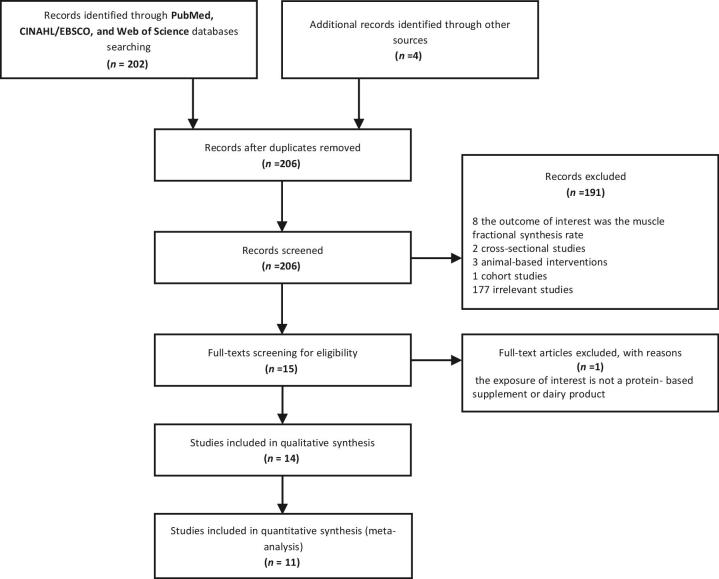

Figure 1 shows the flow of the studies through the review process. A total of 202 articles were identified after the electronic search of PubMed, CINAHL/EBSCO, and Web of Science databases. Four articles were retrieved after the manual search of references of key articles and existing reviews. The abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of 191 articles not meeting inclusion criteria: 8 studies evaluated the increase in the muscle fractional synthesis rate, 5 studies were not randomized controlled trials, 1 study was animal-based, and the remaining studies contained irrelevant content. After the full-text screening for eligibility, one article was excluded for not providing the exposure of interest. A total of 14 studies were therefore included in this systematic review, and 11 were then included in the meta-analysis. The publication dates ranged from 2009 to 2016. The included studies were conducted in Mexico (2), United States (3), Netherlands (3), Iceland (1), Finland (1), Germany (1), Canada (1), Australia (1), and Ireland (1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection of the studies. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study characteristics

Table 3 presents a summary of the characteristics of the included studies. The eligible randomized controlled trials included a total of 1424 participants with a mean ± SD age range between 61 ± 5 y and 81 ± 1 y. Participants’ characteristics varied between studies. Individuals with sarcopenia and polymyalgia rheumatism were recruited in 3 trials (20–22) and 1 trial (23), respectively, whereas the remaining studies enrolled healthy individuals. The subjects were nonfrail and fully mobile in all studies with the exception of 3 in which they had a limited mobility (21, 24, 25).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the randomized controlled trials on dairy protein and the outcome variables of sarcopenia in middle-aged to older adults1

| Study (ref) | Region | Study duration | Age, y | Subjects, n | Sex | Health status | Type of protein | Total amount of protein2 | Comparator | RT frequency | Measured outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alemán-Maeto et al. (20) | Mexico | 3 mo | ≥60 | 40 | F, M | Sarcopenic | Ricotta cheese | 15.7 g/d | Habitual diet | NA | AMM; MS of handgrip; AEs |

| Bauer et al. (21) | Germany | 13 wk | ≥65 | 380 | F, M | Sarcopenic, limited mobility | Whey protein | 40 g/d | Isocaloric drink | NA | AMM, MS of handgrip, SPPB |

| Rondanelli et al. (22) | United States | 12 wk | ≥65 | 130 | F, M | Sarcopenic | Whey protein | 22 g/d | Isocaloric maltodextrin drink | 5 d/wk | MS of handgrip |

| Björkman et al. (23) | Finland | 20 wk | >50 | 46 | F, M | Polymyalgia rheumatic | Whey protein | 14 g/d | Casein-based dairy product | NA | AMM, MS of handgrip |

| Tieland et al. (24) | Netherlands | 24 wk | ≥65 | 65 | F, M | Frail | MPC | 30 g/d | Placebo, carbohydrate drink | NA | AMM; MS of handgrip; MS of leg press; SPPB |

| Chalé et al. (25) | United States | 6 mo | 70–85 | 67 | F, M | Limited mobility | Whey protein | 40 g/d | Isocaloric maltodextrin drink | 3 d/wk | MS of leg press; SPPB |

| Alemán-Maeto et al. (26) | Mexico | 3 mo | ≥60 | 90 | F, M | Healthy | Ricotta cheese | 15.7 g/d | Habitual diet | NA | AMM; MS of handgrip; SPPB, AEs |

| Arnarson et al. (27) | Iceland | 12 wk | 65–91 | 141 | F, M | Healthy | Whey protein | 20 g/d | Isocaloric drink | 3 d/wk | AMM |

| Verreijen et al. (28) | Netherlands | 13 wk | >55 | 65 | F, M | Obese | Whey protein | 20–40 g/d4 | Isocaloric drink | 3 d/wk | AMM; MS of handgrip |

| Karelis et al. (29) | Canada | 135 d | 65–88 | 80 | F, M | Healthy | Cysteine-rich whey protein | 20 g/d | Casein | 3 d/wk | MS of leg press |

| Zhu et al. (30) | Australia | 2 y | 70–80 | 181 | F | Healthy | Skim milk–based high protein | 30 g/d | Skim milk–based supplement | NA | AMM; MS of handgrip |

| Leenders et al. (31) | Netherlands | 24 wk | 70 ± 1 | 57 | F, M | Healthy | MPC | 15 g/d | Placebo, isocaloric drink | 3 d/wk | MS of leg press |

| Verdijk et al. (32) | United States | 12 wk | 72 ± 2 | 28 | F, M | Healthy | Casein hydrolysate | 20 g/d | Placebo, flavored drink | 3 d/wk | MS of leg press |

| Norton et al. (33) | Ireland | 24 wk | 45–60 | 60 | F, M | Healthy | Milk-based protein matrix3 | 0.33 g/kg | Isocaloric drink | NA | AMM |

AE, adverse event; AMM, appendicular muscle mass; MPC, milk-protein concentrate; MS, muscle strength; NA, not available; RT, resistance training; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

The amount of extra protein provided by the test supplement.

The milk protein matrix is composed of a 9:2:1 ratio of milk-protein concentrate, whey-protein concentrate, and whey-protein isolate, respectively.

The 40 g of protein was given on the training days only.

Intervention

The duration of the intervention varied from 12 to 24 wk. The dairy protein supplement used in the IG varied between studies. Two studies provided ricotta cheese with the habitual diet (20, 26). Five studies supplemented whey protein either alone (23, 25) or in combination with leucine and vitamin D (21, 22, 28). Two studies supplemented leucine- (23) and cysteine- (29) enriched whey protein. One study supplemented skimmed milk–based high protein with whey (28). Milk-protein concentrate was given in 2 studies (24, 31), and a milk-based matrix and casein hydrolysate were used in 2 studies as a supplement (32, 33). Only in one study (33) was the amount of protein supplementation reported according to body weight (0.33 g/kg), whereas the remaining studies reported the extra protein intake according to daily amounts ranging from 14 to 40 g/d. In all but 2 trials the protein supplement was given daily; in the 2 studies (27, 32) it was consumed on “training” days only. The frequency of protein supplementation varied among the studies from 1 time/d (22, 27–32), 2 times/d (21, 23–25, 29, 33), or 3 times/d (20, 26). Seven of the included trials (22, 25, 27–29, 31, 32) integrated resistance training as part of the intervention, which ranged from 3 to 5 times/wk.

Comparison

In 2 studies (20, 26), the subjects in the CG were asked to follow their habitual diet. In 6 studies, an isocaloric product was provided as a supplement to the CG (21, 22, 25, 27, 28, 33). Three studies used a placebo supplement (24, 31, 32). A regular dairy product, casein, and skim milk–based supplement were given to the CG in Björkman et al. (23), Karelis et al. (29), and Zhu et al. (30), respectively.

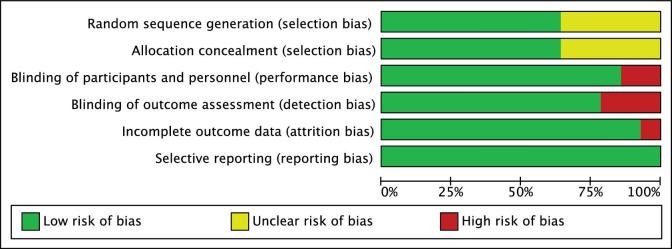

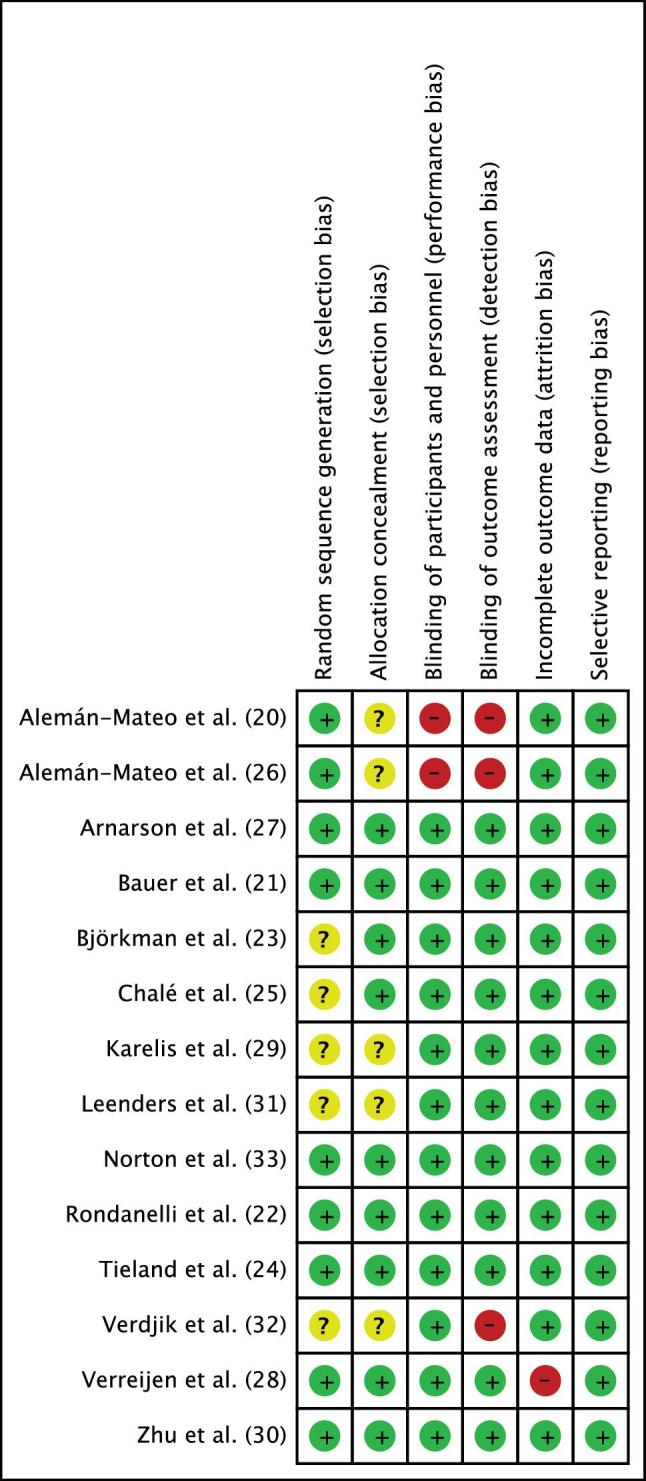

Quality assessment

Figure 2 shows the risk-of-bias graph of the included randomized controlled trials. According to the Cochrane Collaboration tool for risk of bias (18), 64% of the trials reported adequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment, 86% had blinded participants and personnel, 79% had blinded outcome assessors, 93% of the trials addressed adequately the incomplete outcome data, and 100% of the trials were free of selective reporting. The high risk of bias was mainly attributed to performance and detection bias (20, 26, 28) and to attrition bias (28). There was insufficient information to assess the degree of selection bias in 6 trials (20, 23, 25, 26, 29, 31) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Risk-of-bias graph. Review authors’ judgments about each risk-of-bias item presented as percentages across all included studies using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (18).

FIGURE 3.

Risk-of-bias summary. Review authors’ judgments about each risk-of-bias item for each included study using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (18).

Primary outcomes

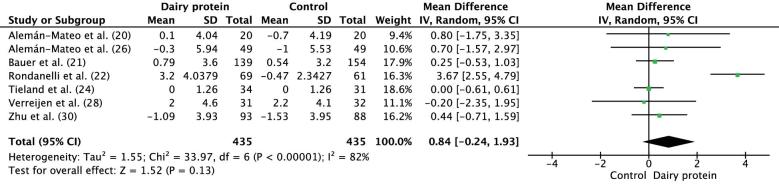

Muscle strength of handgrip

The meta-analysis of the mean differences in mean change in muscle strength of handgrip included 7 studies with 435 participants in each of the IGs and CGs. The dairy protein had no effect on the improvement in handgrip strength (mean difference: 0.84 kg; 95% CI: −0.24, 1.93 kg; P = 0.13) (Figure 4). A significant substantial heterogeneity was shown between the studies (I2 = 82%, P < 0.00001). When a sensitivity analysis was performed, the exclusion of Rondanelli et al. (22) led to the absence of between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), without altering the overall results (mean difference: 0.17 kg; 95% CI: −0.25, 1.59 kg; P = 0.43). Therefore, the results must be interpreted with caution. In Björkman et al. (23), the measurement of handgrip strength of both hands showed a significant decrease in the right handgrip strength (−5.2%; P < 0.001) but did not affect the left handgrip strength (3.7%; P = 0.659) after the consumption of milk protein (IG). The findings of this trial were not included in the analysis due to differences in the way the data was reported.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot showing results for the meta-analysis of difference in mean change from baseline in muscle strength (kilograms) for handgrip after the intervention in middle-aged to older adults. IV, inverse variance.

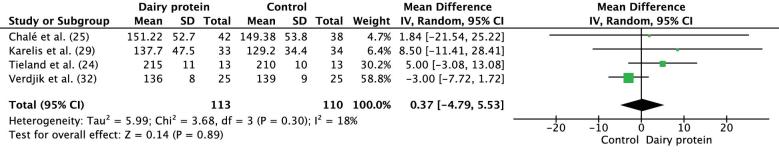

Muscle strength of leg press

The meta-analysis of the mean difference in mean endpoint values of muscle strength of leg press included 4 studies with 114 participants in the IG and 109 participants in the CG. The dairy protein supplementation had no effect on leg press strength, with a mean difference of 0.37 kg (95% CI: −4.79, 5.53 kg; P = 0.89) (Figure 5). Similar findings were obtained when a sensitivity analysis was performed. In Leenders et al. (31), the data were reported as percentage change from the baseline, which was not convenient to be included in the analysis. A significant improvement in leg press strength was found in both women and men after the 24-wk intervention (31% and 26%, respectively; P < 0.001), with no difference between the study arms (P = 0.37)

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot showing results for the meta-analysis of difference in the mean endpoint value of muscle strength for leg press (kilograms) after the intervention in middle-aged to older adults. IV, inverse variance.

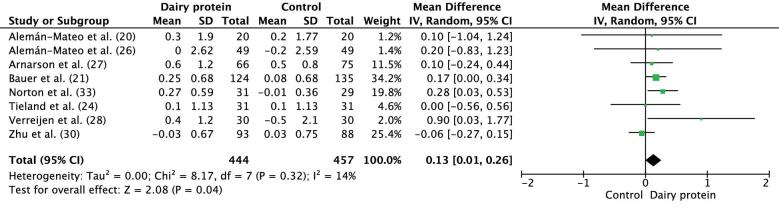

AMM

AMM was assessed in 9 trials, of which 8 were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis of the mean difference in mean change of appendicular muscle mass included a total of 444 and 457 participants in the IGs and CGs, respectively. In comparison to the CG, dairy protein supplementation resulted in a significant increase in AMM (mean difference: 0.13 kg; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.26 kg; P = 0.04) (Figure 6). No changes in the results were detected after a sensitivity analysis was done. Björkman et al. (23) reported no difference in AMM improvement between the groups (IG compared with CG: 0.9% compared with 0.2%; P = 0.510).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot showing results for the meta-analysis of difference in mean change from baseline in appendicular muscle mass (kilograms) after the intervention in middle-aged to older adults. IV, inverse variance.

SPPB

Four out of the 14 included studies evaluated the SPPB (21, 24–26). Tieland et al. (24) and Chalé et al. (25) reported a significant increase in SPPB score from baseline to postintervention compared with the CG [8.9 ± 0.6 to 10 ± 0.6 (P = 0.02) and 8.5 ± 1.1 to 10.3 ± 1.5 (P < 0.0001), respectively], although Alemán-Mateo et al. (26) and Bauer et al. (21) found no effect of dairy protein on the SPPB at the end of the study [10.7 ± 1.7 to 10.8 ± 1.5 (P = 0.55) and 7.5 to 8.36 (P = 0.51), respectively].

Subgroup analyses

A stratified analysis was conducted according to subjects’ health status (with or without sarcopenia), mean age, and amount of extra protein supplementation. The subgroup analysis by sex and type of protein supplement was difficult to be perform due to only 3 out of the 14 included trials (20, 27, 31) reporting sex differences in the main outcomes and to the marked dissimilarity in the given type of protein among the studies. Similarly, the subgroup analysis stratified by the integration of resistance training was not possible to be performed due to differences in the length and type of workout program among the studies. There was no significant change in handgrip strength and AMM across the subgroups (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Subgroup analyses of mean changes in muscle strength for handgrip and AMM according to subjects’ health status, mean age, and amount of protein consumed1

| Changes in handgrip strength, kg | Changes in AMM, kg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Effect (95% CI) | P | I 2, % | n | Effect (95% CI) | P | I 2, % | |

| Health status | ||||||||

| With sarcopenia | 3 | 1.62 (−0.94, 4.18) | 2 | 0.17 (0.00, 0.33) | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Without sarcopenia | 4 | 0.11 (−0.40, 0.62) | 6 | 0.13 (−0.07, 0.33) | ||||

| Amount of protein | ||||||||

| <20 g/d | 3 | 0.74 (−0.95, 2.44) | 3 | 0.30 (−0.57, 0.96) | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| ≥20 g/d | 4 | 0.86 (−0.44, 2.17) | 5 | 0.14 (−0.02, 0.29) | ||||

| Mean age | ||||||||

| >65 y | NA | 6 | 0.45 (−0.09, 0.98) | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| ≤65 y | 2 | 0.08 (−0.03, 0.20) | ||||||

AMM, appendicular muscle mass; NA, not available.

Secondary outcomes

Nine of the included studies included adverse events in their reporting. The assessment of safety and tolerability of the study supplements varied between studies. For instance, Alemán-Mateo et al. (20, 26) measured the relative change of lipid profile, glomerular filtration rate, kidney function markers, and microalbuminuria. In the 7 remaining trials, the gastrointestinal tolerance of the supplement was assessed. None of the included trials found a significant difference in the incidence of serious adverse events between study arms. Alemàn-Mateo et al. (20) found that the consumption of ricotta cheese was associated with early satiety among 25% of the female participants, and Björkman et al. (23) found that some gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., early satiety, diarrhea, flatulence, and nausea) were reported by 44.7% in the IG compared with 32.6% participants in the CG (P = 0.180).

The intervention product was generally well tolerated, and the compliance rate ranged from 72.1% to 100% among the studies. In Zhu et al. (30), the adherence to the intervention was significantly higher in the IG compared with the CG (87.1% compared with 80.8%, respectively; P = 0.03).

Discussion

The aim of this review was to determine if dairy proteins could be used to reduce the health risks associated with sarcopenia by improving muscle mass, muscle function, and physical performance in middle-aged to older adults. A meta-analysis was performed to assess the improvement in muscle strength of handgrip and leg press and AMM. The results showed a significant favorable effect of dairy protein, at amounts of 14–40 g/d, on AMM without having an effect on muscle strength of handgrip and leg press. Overall, compliance and acceptability of the protein supplementation were reported to be good across the studies. Differences in the amount of protein supplementation and subjects’ mean age and baseline health status between the studies did not significantly influence the findings.

Previous studies have reported a direct relation between muscle mass and strength in middle-aged to older adults. Hayashida et al. (34) conducted a cross-sectional study in 318 individuals with the aim to evaluate the correlation between muscle mass and muscle strength on the basis of sex and age groups. The obtained results confirmed a significant association between muscle strength and AMM in men aged ≥65 y and women aged ≥75 y; however, Goodpaster et al. (35) suggested in a prospective study in 1880 older adults with a mean age of 73.5 ± 2.8 y that the loss of muscle strength is more rapid than the loss of muscle mass and that the decline in the age-dependent strength cannot be explained by the loss of muscle mass alone.

It was previously argued that older adults tend to develop a phenomenon called anabolic resistance, an impaired response of skeletal muscle to an anabolic stimulus with normal muscle protein synthesis (36). Nevertheless, Burd et al. (36) observed that, although many factors contribute to the anabolic resistance of muscle protein synthesis in older adults, minimal differences could be seen in muscle protein synthesis rates between young and older adults after protein ingestion (36). Hence, the diversity of age groups in this review probably has little impact on the significant improvement of AMM reported (P = 0.04).

With regard to physical performance, the analyzed data do not allow us to make any conclusions about the potential effect of dairy protein on SPPB score in middle-aged to older adults. Two of the included trials reported a significant increase in SPPB score (24, 25). In Bauer et al. (21), although the results showed no difference in SPPB score between the groups (P = 0.51), a significant improvement in chair-rise time was reported in the IG compared with the CG (P = 0.018). A better chair-stand performance has been shown to be related to a better leg extensor power in middle-aged and older adults (37). Cesari et al. (38) claimed that the chair-stand test has the highest prognostic value compared with the other SPPB subtasks. Because the chair stand has been suggested as a useful measure of physical function, this could partially explain the potential benefits of dairy protein on physical performance.

There are limited scientific data on dairy protein and sarcopenia available. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to determine the impact of dairy protein intake on muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in middle-aged to older adults with or without existing sarcopenia. However, the findings of the review are limited and the following factors must be considered when interpreting the results. First, there were differences in health status (sarcopenic compared with healthy subjects) and physical functionality (e.g., frailty and mobility) of the participants in the included trials at baseline. According to Alemán-Mateo et al. (26), the responsiveness to the anabolic stimulus of protein supplementation is likely to be more effective in healthy subjects than in those with sarcopenia. Second, the amount, regimen, form of administration (food compared with supplements), and types of dairy protein used (e.g., whey, milk-protein concentrate, casein) varied between the studies (Table 3), which makes it challenging to interpret the findings. Third, the baseline dietary protein intake, an important confounding factor, was only measured in 7 of the included trials (21, 24, 25, 31–33). Campbell and Leidy (39) affirmed that protein supplementation induces a significant enhancement in muscle mass and strength in individuals with a habitual dietary protein intake below the RDA (<0.8 g ⋅ kg−1 ⋅ d−1), and this was consistent with the results of Verdjik et al. (32) and Tieland et al. (24). Only Bauer et al. (21) adjusted for baseline dietary protein intake. This might have influenced the precision of the findings and created bias.

Dairy protein was not the only supplement in all the trials. Bauer et al. (21), Verreijen et al. (28), and Rondanelli et al. (22) enriched the dairy protein supplement with leucine and vitamin D. Dairy protein, such as native whey, is naturally a good source of the essential amino acid leucine, which has been reported to stimulate protein synthesis and enhance muscle mass and function (40, 41). In addition, vitamin D has been shown to induce a significant positive impact on muscle strength in the elderly (42). Therefore, the absence of adjustment of the postintervention serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in addition to the anabolic effect of leucine could have created an overestimation of the positive effect of dairy protein in these trials and thus have limited the accuracy of the findings.

A further confounding factor is the incorporation of physical activity in some of the included studies. In Verdjik et al. (32) and Chalé et al. (25), the study arms were involved in resistance training 3 times/wk. The authors reported a significant improvement in muscle strength in both groups, regardless of the consumption of protein supplementation, which underlines the possible effect of physical activity on the outcomes.

Overall, 6 trials were of a high quality and had all the key domains at low risk of bias. The high risk of bias in certain trials was attributable to the lack of blinding of participants and/or outcome assessors (20, 26, 32) and to missing data of the primary outcome (28). Thus, the accuracy of the findings of these trials might be limited and should be interpreted with caution. Although in some studies the allocation was stated to be randomly generated and concealed, a detailed description of the methods used was not clearly reported. This has raised some uncertainty about the results and rendered the judgment of risk of bias as unclear.

This systematic review has several limitations: 1) broad inclusion criteria with minimal restrictions on the type of intervention; 2) the presence of a high degree of heterogeneity in the data reporting among the studies; 3) lack of adjustment for baseline protein intake; 4) lack of publication bias assessment; 5) lack of postintervention follow-up to evaluate the long-term effect of dairy protein supplementation; 6) the relatively small sample sizes, which influences the external validity of the trials and restricts the findings to be generalized to the entire population; 7) lack of blinding of participants and outcome assessors and incomplete data reporting increased the risk of bias in certain trials (Figure 3) and thus affected the results of the meta-analysis; 8) only 6 of the included studies were of high quality; 9) lack of subgroup analysis stratified by gender, type of protein, and the integration of resistance training; 10) the methodologic diversity between the studies; and 11) the assessment of muscle mass does not predict the physical functioning (4).

However, the systematic review and meta-analysis also has the following strengths: 1) this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to highlight the possible effect of dairy protein consumption on the outcome variables of sarcopenia, which could be clinically meaningful for the general population; 2) the review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement (13); 3) all the measuring tools that were used to assess the outcomes of interest were proved to be valid and reliable and thus can be applied in clinical and research settings; 4) the inclusion of a considerable number of studies in the meta-analysis; 5) despite the diversity in the provided type of dairy protein, all of the included trials reported a high adherence and tolerance to the exposure, which confirmed the safety of protein supplementation; and 6) the assessment of handgrip strength, which is a good indicator of physical capability (4).

In conclusion, the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that dairy proteins, at an amount of 14–40 g/d, can significantly increase the AMM in middle-aged and older adults without a significant clinical effect on muscle strength of handgrip and leg press. The effect of dairy protein on the SPPB was inconclusive due to insufficient reported data. This review highlights the need for larger-scale and high-quality randomized controlled trials with longer follow-ups using standardized primary outcomes (muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance) when investigating the role of dairy protein in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia; to establish the optimal type, amount, timing, and frequency of dairy protein supplementation in middle-aged to older adults; and subsequently, to examine its clinical effectiveness in the improvement of the primary outcomes of sarcopenia in middle-aged to older adults.

Acknowledgments

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

The authors declared no financial support received for this work.

Author disclosures: NIH, FM, and AA, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: AMM, appendicular muscle mass; CG, control group; IG, intervention group; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

References

- 1. Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr 1997;127(5):990S–1S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mitchell CJ, McGregor RA, D'Souza RF, Thorstensen EB, Markworth JF, Fanning AC, Poppitt SD, Cameron-Smith D. Consumption of milk protein or whey protein results in a similar increase in muscle protein synthesis in middle aged men. Nutrition 2015;7(10):8685–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ethgen O, Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Bruyère O, Reginster JY. The future prevalence of sarcopenia in Europe: a claim for public health action. Calcif Tissue Int 2017;100(3):229–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, Martin FC, Michel JP, Rolland Y, Schneider SM et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39(4):412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(1):80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malafarina V, Uriz-Otano F, Iniesta R, Gil-Guerrero L. Effectiveness of nutritional supplementation on muscle mass in treatment of sarcopenia in old age: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(1):10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooper LA, Brown SL, Hocking E, Mullen AC. The role of exercise, milk, dairy foods and constituent proteins on the prevention and management of sarcopenia. Int J Dairy Tech 2016;69(1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baum JI, Wolfe RR. The link between dietary protein intake, skeletal muscle function and health in older adults. Healthcare 2015;3(3):529–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coker RH, Miller S, Schutzler S, Deutz N, Wolfe RR. Whey protein and essential amino acids promote the reduction of adipose tissue and increased muscle protein synthesis during caloric restriction-induced weight loss in elderly, obese individuals. Nutr J 2012;11(1):105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cermak NM, de Groot LC, Saris WH, van Loon LJ. Protein supplementation augments the adaptive response of skeletal muscle to resistance-type exercise training: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96(6):1454–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilkinson SB, Tarnopolsky MA, MacDonald MJ, MacDonald JR, Armstrong D, Phillips SM. Consumption of fluid skim milk promotes greater muscle protein accretion after resistance exercise than does consumption of an isonitrogenous and isoenergetic soy-protein beverage. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85(4):1031–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hidayat K, Chen GC, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Dai X, Szeto IM, Qin LQ. Effects of milk proteins supplementation in older adults undergoing resistance training: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Nutr Health Aging 2018;22(2):237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG;. PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oxford English Dictionary [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Jun 6]. Available from: http://www.oed.com/.

- 15. Raguso CA, Kyle U, Kossovsky MP, Roynette C, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Hans D, Genton L, Pichard C. A 3-year longitudinal study on body composition changes in the elderly: role of physical exercise. Clin Nut 2006;25(4):573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meredith CN, Frontera WR, O'Reilly KP, Evans WJ. Body composition in elderly men: effect of dietary modification during strength training. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40(2):155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, Leveille SG, Markides KS, Ostir GV, Studenski S, Berkman LF, Wallace RB. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gereontol 2000;55(4):M221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alemán-Mateo H, Macías L, Esparza-Romero J, Astiazaran-García H, Blancas AL. Physiological effects beyond the significant gain in muscle mass in sarcopenic elderly men: evidence from a randomized clinical trial using a protein-rich food. Clin Interv Aging 2012;7:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bauer JM, Verlaan S, Bautmans I, Brandt K, Donini LM, Maggio M, McMurdo ME, Mets T, Seal C, Wijers SL et al. Effects of a vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement on measures of sarcopenia in older adults, the PROVIDE study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16(9):740–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rondanelli M, Klersy C, Terracol G, Talluri J, Maugeri R, Guido D, Faliva MA, Solerte BS, Fioravanti M, Lukaski H et al. Whey protein, amino acids, and vitamin D supplementation with physical activity increases fat-free mass and strength, functionality, and quality of life and decreases inflammation in sarcopenic elderly. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103(3):830–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Björkman MP, Pilvi TK, Kekkonen RA, Korpela R, Tilvis RS. Similar effects of leucine rich and regular dairy products on muscle mass and functions of older polymyalgia rheumatica patients: a randomized crossover trial. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15(6):462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tieland M, van de Rest O, Dirks ML, van der Zwaluw N, Mensink M, van Loon LJ, de Groot LC. Protein supplementation improves physical performance in frail elderly people: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13(8):720–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chalé A, Cloutier GJ, Hau C, Phillips EM, Dallal GE, Fielding RA. Efficacy of whey protein supplementation on resistance exercise–induced changes in lean mass, muscle strength, and physical function in mobility-limited older adults. J Gereontol 2012;68(6):682–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alemán-Mateo H, Carreón VR, Macías L, Astiazaran-García H, Gallegos-Aguilar AC, Enríquez JR. Nutrient-rich dairy proteins improve appendicular skeletal muscle mass and physical performance, and attenuate the loss of muscle strength in older men and women subjects: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Clin Int Aging 2014;9:1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arnarson A, Gudny Geirsdottir O, Ramel A, Briem K, Jonsson PV, Thorsdottir I. Effects of whey proteins and carbohydrates on the efficacy of resistance training in elderly people: double blind, randomised controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2013;67(8):821–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verreijen AM, Verlaan S, Engberink MF, Swinkels S, de Vogel-van den Bosch J, Weijs PJ. A high whey protein–, leucine-, and vitamin D–enriched supplement preserves muscle mass during intentional weight loss in obese older adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101(2):279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karelis A, Messier V, Suppère C, Briand P, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Effect of cysteine-rich whey protein (Immunocal) supplementation in combination with resistance training on muscle strength and lean body mass in non-frail elderly subjects: a randomized, double-blind controlled study. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19(5):531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu K, Kerr DA, Meng X, Devine A, Solah V, Binns CW, Prince RL. Two-year whey protein supplementation did not enhance muscle mass and physical function in well-nourished healthy older postmenopausal women. J Nutr 2015;145(11):2520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leenders M, Verdijk LB, Van der Hoeven L, Van Kranenburg J, Nilwik R, Wodzig WK, Senden JM, Keizer HA, Van Loon LJ. Protein supplementation during resistance-type exercise training in the elderly. Med Sci Sports 2013;45(3):542–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verdijk LB, Jonkers RA, Gleeson BG, Beelen M, Meijer K, Savelberg HH, Wodzig WK, Dendale P, van Loon LJ. Protein supplementation before and after exercise does not further augment skeletal muscle hypertrophy after resistance training in elderly men. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(2):608–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Norton C, Toomey C, McCormack WG, Francis P, Saunders J, Kerin E, Jakeman P. Protein supplementation at breakfast and lunch for 24 weeks beyond habitual intakes increases whole-body lean tissue mass in healthy older adults. J Nutr 2016;146(1):65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hayashida I, Tanimoto Y, Takahashi Y, Kusabiraki T, Tamaki J. Correlation between muscle strength and muscle mass, and their association with walking speed, in community-dwelling elderly Japanese individuals. PloS One 2014;9(11):e111810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt M, Schwartz AV, Simonsick EM, Tylavsky FA, Visser M, Newman AB. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Gereontol 2006;61(10):1059–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burd NA, Gorissen SH, van Loon LJ. Anabolic resistance of muscle protein synthesis with aging. Exec Sport Sci Rev 2013;41(3):169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hardy R, Cooper R, Shah I, Harridge S, Guralnik J, Kuh D. Is chair rise performance a useful measure of leg power?. Aging Clin Exp Res 2010;22(5–6):412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cesari M, Onder G, Zamboni V, Manini T, Shorr RI, Russo A, Bernabei R, Pahor M, Landi F. Physical function and self-rated health status as predictors of mortality: results from longitudinal analysis in the ilSIRENTE study. BMC Geriatr 2008;8(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Campbell WW, Leidy HJ. Dietary protein and resistance training effects on muscle and body composition in older persons. J Am Coll Nutr 2007;26(6):696S–703S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, Cesari M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Morley JE, Phillips S, Sieber C, Stehle P, Teta D et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(8):542–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hamarsland H, Nordengen AL, Aas SN, Holte K, Garthe I, Paulsen G, Cotter M, Børsheim E, Benestad HB, Raastad T. Native whey protein with high levels of leucine results in similar post-exercise muscular anabolic responses as regular whey protein: a randomized controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nut 2017;14(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Rabenda V, Gillain S, Cavalier E, Slomian J, Petermans J, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle power: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Endocrinol Metab 2014;99(11):4336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]