Abstract

FGF signaling plays important roles in many aspects of mammalian development. Fgfr1−/− and Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− mouse embryos on a 129S4 co-isogenic background fail to survive past the peri-implantation stage, whereas Fgfr2−/− embryos die at midgestation and show defects in limb and placental development. To investigate the basis for the Fgfr1−/− and Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− peri-implantation lethality, we examined the role of FGFR1 and FGFR2 in trophectoderm (TE) development. In vivo, Fgfr1−/− TE cells failed to downregulate CDX2 in the mural compartment and exhibited abnormal apicobasal ECadherin polarity. In vitro, we were able to derive mutant trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) from Fgfr1−/− or Fgfr2−/− single mutant, but not from Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− double mutant blastocysts. Fgfr1−/− TSCs however failed to efficiently upregulate TE differentiation markers upon differentiation. These results suggest that while the TE is specified in Fgfr1−/− mutants, its differentiation abilities are compromised leading to defects at implantation.

Keywords: FGF, Trophectoderm, TS cells

Introduction

By the time of implantation, the late mouse blastocyst consists of three segregated lineages, the epiblast (EPI), the primitive endoderm (PrE) and the trophectoderm (TE). Both the EPI and the PrE originate from the inner cell mass (ICM) and give rise to the fetus proper and components of the yolk sac, respectively. The outside cells form the TE epithelium and contribute to the placenta which supplies the embryo with nutrients.

Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) signal through four FGF receptor tyrosine kinases (FGFR1-FGFR4) and engage a number of signaling pathways including ERK1/2, PLCγ and PI3K (reviewed in (Brewer et al., 2016). FGF signaling plays an important role in preimplantation development. This was initially demonstrated in Fgf4−/− mice which die at the peri-implantation stage (Feldman et al., 1995; Goldin and Papaioannou, 2003; Kang et al., 2013). Further analyses revealed that the FGF/MEK/ERK1/2 signaling pathway plays an essential role in the specification of the PrE (Brewer et al., 2015; Chazaud et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2013; Molotkov et al., 2017; Molotkov and Soriano, 2018; Nichols et al., 2009; Yamanaka et al., 2010).

Previous publications have shown that on a mixed genetic background, a proportion of Fgfr1−/− embryos are lost prior to or at gastrulation (Ciruna and Rossant, 2001; Deng et al., 1994; Kang et al., 2017; Yamaguchi et al., 1994), with cells failing to complete the epithelial to mesenchymal (EMT) transition required for mesoderm formation (Ciruna and Rossant, 2001). On a co-isogenic 129S4 genetic background however, Fgfr1−/− embryos show increased number of epiblast cells at the expense of PrE cells and fail to progress beyond implantation (Brewer et al., 2015). It was recently shown that loss of both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 leads to the complete absence of PrE cells, with Fgfr1 playing the predominant role (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017). Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− double mutants also fail to progress past implantation (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017). However, an intrinsic deficiency that would affect only the PrE is unlikely to explain peri-implantation lethality, and we therefore sought to examine TE development.

FGF signaling plays an important role in placental development and is required for the derivation of trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) from the TE (Tanaka et al., 1998). Removal of FGF4 from culture medium leads to TSC differentiation into giant cells (Tanaka et al., 1998). An important mediator of FGF signaling, ERK2, has been shown to regulate TE development and the development of the placenta (Hatano et al., 2003; Saba-El-Leil et al., 2003). Furthermore, it has been shown that the binding and phosphorylation of the adaptor protein FRS2, which links FGFR1 to ERK1/2 signaling, is essential for TSC self-renewal and proliferation (Ong et al., 2000).

Here we show that in vivo, FGFR1 and FGFR2 are strongly expressed in the TE of newly implanted blastocysts at Embryonic day (E) 4.5 and in the extraembryonic ectoderm at E5.5. We find that E4.5 Fgfr1−/− embryos show altered TE cell morphology and E-Cadherin expression, and fail to downregulate Cdx2 in the mural TE where implantation is initiated. Interestingly, Fgfr1−/− TSCs could be derived and cultured indefinitely, but show diminished expression of TE lineage markers upon removal of FGF from culture medium. This suggests that in vitro Fgfr1 is dispensable for TSC proliferation and maintenance, but may be required for further differentiation along specific TE lineages. Fgfr2−/− TSCs could be isolated and showed no defects in differentiation. However, we were unable to recover Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− double null TSCs. These results indicate an important role for FGF signaling through FGFR1/2 in TE development, implantation and in TSC establishment and differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Fgfr1lox/lox mice (Hoch and Soriano, 2006), Fgfr2lox/lox mice (Molotkov et al., 2017), Fgfr1T2A-H2B-GFP further referred to as Fgfr1GFP (Molotkov et al., 2017), Fgfr2T2A-H2B-mCherry mice further referred to as Fgfr2mCherry (Molotkov et al. 2017) were maintained on a 129S4/SvJaeSor (MGI:3044540) co-isogenic background, further referred to as 129. Fgfr1- and Fgfr2- alleles were generated from the floxed alleles by crossing with epiblast specific Meox2Cre mice (Tallquist and Soriano, 2000), also on the 129 background, and subsequently crossing out the Cre driver. All animal experimentation was conducted according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Cell culture and manipulation

AK7.1 mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were cultured in 2i/LIF as described (Kunath et al., 2007; Mulas et al., 2017). Wild-type and Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− ESCs were transfected with a linearized pPyCAG-Cdx2ERT2-IP plasmid (Niwa et al., 2005) using Lipofectamine 2000 and cells were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin. Stably transfected and resistant clones were picked and expanded. The resulting ESCs lines were cultured for two weeks in TSC medium (Ohinata and Tsukiyama, 2014) with 1 μg/ml 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) to induce Cdx2 expression and obtain TSC colonies on fibronectin.

TSCs from E4.5 blastocysts were derived and cultured in N2B27 complemented with 5 nM Y27632, 10 nM XAV939, 20 ng/ml Activin A and 12.5 ng/ml FGF2 as described (Ohinata and Tsukiyama, 2014). Fgfr1floxed/floxedFgfr2floxed/floxed and Fgfr1floxed/+Fgfr2floxed/+ TSCs were transfected with Cre-IRES-Blasticidin (Austin Smith, unpublished) or linearized CreERT2-IRES-Blasticidin plasmids (Betschinger et al., 2013) using Lipofectamine 2000. The resulting TSCs colonies were cultured for 24 h in TSC medium with 1 μg/ml 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) to induce Cre recombination and selected 48h with 1 μg/ml blasticidin. pPyCAG-Cdx2ERT2-IP, Cre-IRES-Blasticidin and CreERT2-IRES-Blasticidin were kindly provided by Austin Smith and Ken Jones.

Embryo dissection and culture

Homozygous Fgfr1GFPFgfr2mCherry, or Fgfr1+/− male and female mice were naturally mated and checked every morning for the appearance of a vaginal plug on E0.5. E3.5 embryos were flushed from the uterus and cultured in DMEM for 48h. E4.5 and E5.5 embryos were dissected from the uterus and processed for immunostaining.

RT-qPCR

mRNA from TSCs was isolated using QIAGEN RNA-easy kit (74106, Qiagen), cDNA was prepared using Superscript II first strand system (18064014, Invitrogen). qPCR was run on an iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (BioRad) using Perfecta Sybr Green master mix (101414–264, VWR). All primer sequences were derived from qPrimerDepot (Cui et al., 2007) and exon-exon spanning pairs were chosen as shown in supplementary Table 1. Graphs were created using Excel.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunostaining was performed essentially as described (Nichols et al., 2009). Embryos or TSCs were fixed 15 minutes in 4% PFA, permeabilized for 30 minutes in 0.5% Triton X100 (T9284, Sigma) and 3 mg/ml PVP in PBS, blocked in 0.1% BSA with 2% donkey serum in 0.25% Triton X100 in PBS/PVP for a minimum of 30 minutes and incubated overnight with primary antibodies used at 1/200 dilution. Primary antibodies used: NANOG (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd, RCAB0002P-F), CDX2 (MU392A-UC, BioGenex), GATA6 (AF1700, R&D Systems), E-Cadherin (R&D Systems, AF1700), GFP (Invitrogen A6455), mCHERRY (Abcam ab167453), OCT3/4 (Santa Cruz, sc-5279). On the next day, embryos were washed in PBST and incubated for 1 h with secondary Alexa Fluor (Invitrogen) conjugated antibodies diluted 1/500 in 1% donkey serum in PBST. Blastocysts and TSCs were counterstained with DAPI and mounted in Vectashield. Confocal images were taken using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. Optical section images were taken on a Zeiss Axio-Observer Z1 with an Apotome 2 attachment, using a Hamamatsu Orca Flash 4.0 LT camera and ZenPro 2015 software. LAS AF Lite was used to visualize confocal images and to create the intensity heat maps using the pre-defined LUT spectrum visualization settings. PAST 3.19 Paleontological Statistics software (Hammer et al., 2001) was used to create the box plot graphs.

Results

FGFR1 and FGFR2 are highly expressed in TE lineages of peri- and post-implantation embryos and in TSCs in vitro.

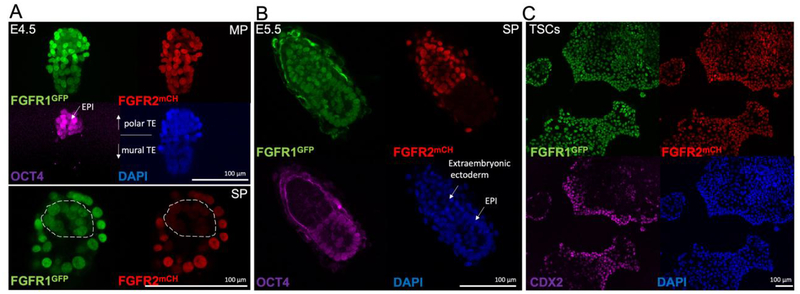

To assess the expression of FGFR1 and FGFR2 in the peri-implantation embryo and in TSCs, we used our previously described Fgfr1GFP and Fgfr2mCHERRY fluorescent knock-in reporter mouse lines, in which we had shown that both receptors are co-expressed in the TE at E3.5 (Molotkov et al., 2017). To assess FGFR1/2 expression at later stages, we dissected E4.5 and E5.5 embryos from decidua and show that Fgfr1GFP is expressed more strongly in the TE and extraembryonic ectoderm than in the OCT4+ epiblast (EPI) cells (Figure 1A, B). Fgfr2mCHERRY is strongly expressed in the TE at E4.5 and in the extraembryonic ectoderm and visceral endoderm in E5.5 embryos. It is faintly detectable in Oct4+ EPI cells at E4.5, and is absent in the E5.5 EPI (Figure 1A, B). Both reporters are expressed in CDX2+ TSCs derived from Fgfr1GFP/GFPFgfr2mCHERRY/mCHERRY blastocysts (Figure 1C). Taken together, these results show that FGFR1 and FGFR2 are co-expressed in TE and TE derived cells, as well as in TSCs in vitro.

Figure 1. FGFR1 and FGFR2 are expressed in the TE and the extraembryonic ectoderm.

A, Maximal projection (MP) of confocal immunofluorescence images of FGFR reporter embryos showing strong FGFR1GFP and FGFR2mCHERRY expression in the TE of E4.5 blastocysts. OCT4 expression marks the EPI. The single plane (SP) image through the EPI clearly detects FGFR1GFP expression in the ICM, whereas FGFR2mCHERRY is weakly expressed. The dashed line was drawn around cells which expressed OCT4. B, at E5.5 FGFR1GFP is expressed throughout embryonic- and extraembryonic tissues. FGFR2mCHERRY is restricted to the extraembryonic ectoderm. OCT4 marks the EPI. C, both receptors are expressed in CDX2 positive TSCs. DAPI shows nuclei.

Fgfr1−/− blastocysts fail to maintain TE polarity.

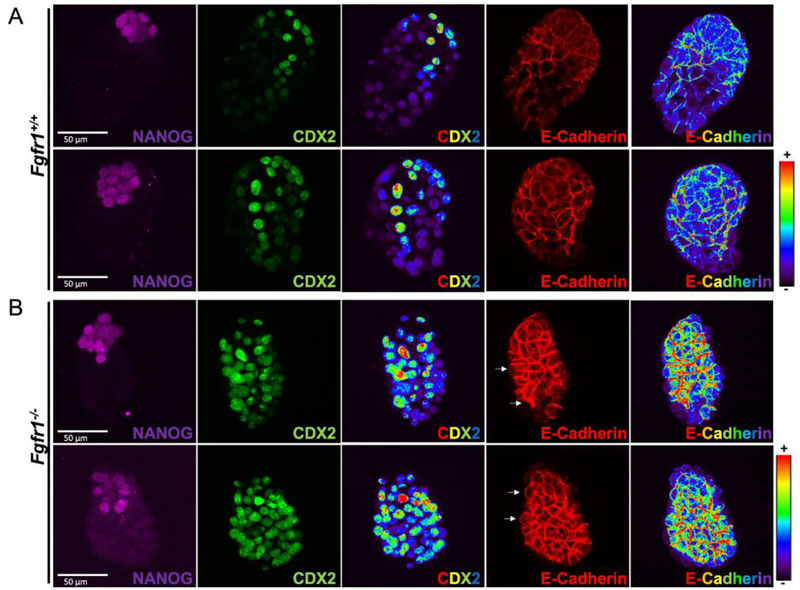

Next, we examined Fgfr1−/− blastocysts at implantation (E4.5) just prior to Fgfr1−/− lethality on the 129 background (Brewer et al., 2015). We investigated TE development by following the expression of CDX2 in E4.5 blastocysts. At this stage the mural TE differentiates into giant cells to ensure implantation of the embryo. CDX2 was downregulated in the mural TE of control blastocysts (Figure 2A). Remarkably, CDX2 expression was maintained at high levels in Fgfr1−/− blastocysts throughout the TE (Figure 2B), suggesting a differentiation defect. A characteristic of the TE is its tight junctions between cells which maintain the blastocoel cavity (Fleming and Johnson, 1988). Another important cell interaction between adjacent cells in the TE are the adherens junctions (Fleming et al., 1991). We therefore analyzed expression of ECadherin, which localizes to the basolateral adherens junctions. While E-Cadherin expression was restricted to the basolateral membranes in wild type TE cells (Figure 2A, Figure 3A), Fgfr1−/− TE cells exhibited very strong basal expression as well as additional apical E-Cadherin localization (Figure 2B, Figure 3A). Heatmaps in Figure 2 show the intensity of CDX2 and E-Cadherin expression throughout the blastocysts (blue low, red high), both proteins are visibly more highly expressed in Fgfr1−/− TE cells. This phenotype was 100% penetrant in Fgfr1−/− blastocysts (n=7) and strikingly similar to that observed in Cdx2−/− blastocysts which also fail to generate a functional TE and show peri-implantation lethality (Strumpf et al., 2005). Additionally, we observed an increase in the apicobasal distance of TE cells of Fgfr1−/− embryos, relative to control (Figure 3B, C), which may reflect a loss of cell tension within the TE. In turn, the abnormal apposition of TE cells may lead to a leaky epithelial lining surrounding the blastocoel cavity, explaining why none of the Fgfr1−/− blastocysts showed a fully expanded cavity (Figure 3). Although all Fgfr1−/− embryos hatched out of their zona pellucida, the trophectoderm defect may subsequently interfere with implantation (White et al., 2018).

Figure 2. E4.5 FGFR1−/− TE is specified but the expression of CDX2 and E-Cadherin is abnormal.

A and B, maximal projection confocal immunofluorescence images of wild type and Fgfr1−/− E4.5 blastocysts showing NANOG, CDX2 and E-Cadherin expression. A, wild type E4.5 blastocysts show downregulated CDX2 expression in the mural TE and basolateral E-Cadherin expression in TE cells. NANOG marks the EPI cells. Heat maps show the intensity of CDX2 and E-Cadherin expression. B, Fgfr1−/− blastocysts maintain high CDX2 expression throughout the TE and show strong basolateral and abnormal apical E-Cadherin expression (arrows).

Figure 3. Fgfr1−/− blastocysts at E4.5 show abnormal TE cell polarity and an increased apicobasal distance.

A, Single plane confocal immunofluorescence image of wild type and Fgfr1−/− E4.5 blastocysts showing basolateral E-Cadherin expression in TE cells and basolateral and apical expression in Fgfr1−/−. Insets show enlarged single TE cells and depict the apical (a) and basal (b) cell membranes. B and C, confocal plane section images showing that the apicobasal distance of TE cells of Fgfr1−/− embryos is increased in comparison to TE cells of control embryos. C, quantification of TE cell apicobasal distance of two Fgfr1+/+ and two Fgfr1−/− embryos. Cells measured in A and B are quantified in C.

Interestingly, E4.5 Fgfr1−/− embryos could only be recovered in Mendelian proportions (6/19) by flushing the uterus. Attempts to dissect embryos from implantation sites at E4.5 only yielded two Fgfr1−/− embryos among 47 blastocysts, with no increase in the proportion of empty decidua. Taken together, these results suggest that Fgfr1−/− TE cells show altered polarity and fail to differentiate, hindering embryo implantation.

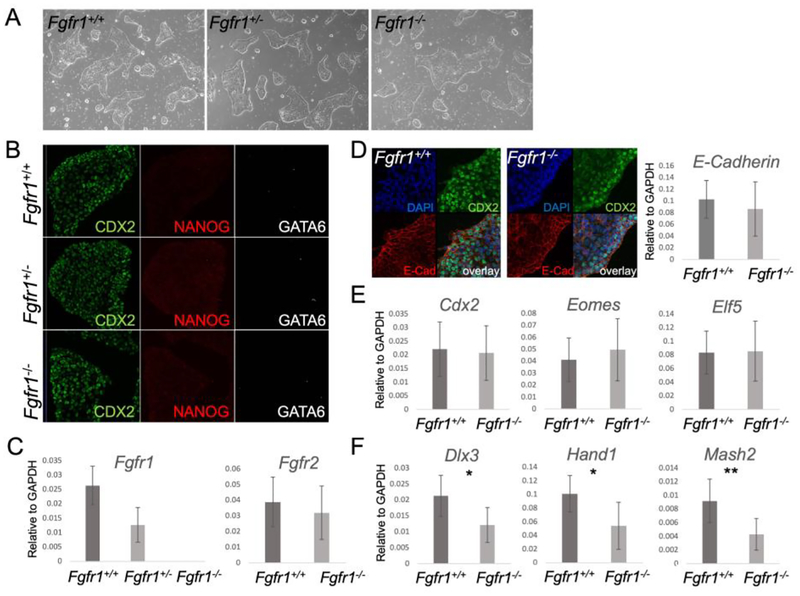

Fgfr1−/− TSCs exhibit a defective differentiation potential.

To further investigate the requirement of Fgfr1 in TE development, we sought to derive Fgfr1−/− TSCs. Blastocysts were obtained from heterozygous Fgfr1+/− mouse intercrosses and TSCs were derived in chemically defined culture medium (Ohinata and Tsukiyama, 2014). We successfully derived TSCs from eighty-three E3.5 blastocyst outgrowths obtained from super ovulated females, twenty of these were genotyped by PCR as Fgfr1−/−. Fgfr1−/− TSCs showed no morphological differences compared to wild type or heterozygous TSCs (Figure 4A) and could be propagated for over 20 passages. Using immunofluorescence, we found that wild type and mutant TSCs showed robust CDX2 expression and no expression of the pluripotency marker NANOG or the PrE marker GATA6 (Figure 4B). Fgfr1 mRNA was absent in Fgfr1−/− TSCs (Figure 4C). To test whether Fgfr2 is upregulated in Fgfr1−/− TSCs we performed further RT-qPCRs. In Fgfr1−/− and Fgfr1+/+ TSCs the levels were similar, indicating no compensation by Fgfr2 in mutant cells (Figure 4C). In contrast to the results obtained in vivo, E-Cadherin showed no differences in protein levels and localization, or mRNA expression (Figure 4D). To further characterize the TSC lines, we analyzed the expression of TSC and TE differentiation markers. The expression of TSC markers showed no significant alterations in Fgfr1−/− TSCs compared to control cell lines (Figure 4E). However, the differentiation markers Dlx3 (labyrinthine layer), Hand1 (giant cells) and Mash2 (spongiotrophoblast) showed significantly lower expression in Fgfr1−/− TSCs (Figure 4F). This might indicate an altered differentiation potential of Fgfr1−/− TSCs, consistent with our in vivo observations. To further assess the differentiation potential of Fgfr1−/− TSCs, we removed FGF4 from the culture medium, which forces wild type TSCs to spontaneously differentiate into all three TE lineages (Ohinata and Tsukiyama, 2014). Differentiated Fgfr1−/− or wild type cells showed no morphological differences (Figure 5A). The expression of Cdx2, Eomes and Elf5 was downregulated 24h and 48h following FGF removal in both wild type and Fgfr1−/− lines (Figure 5B) and showed no significant differences. However, Fgfr1−/− TSCs failed to upregulate the expression of TEderived lineage markers Dlx3, Mash2 and Hand1 to the same extent as wild type TSCs (Figure 5C), further supporting an inherent defect in differentiation.

Figure 4. Fgfr1−/− TSCs can be derived and maintained in culture.

A, brightfield images showing similar morphology of control and Fgfr1−/− TSCs. B, confocal immunofluorescence images, showing the expression of the TSC marker CDX2 and absence of PrE or EPI blastocyst markers (GATA6 and NANOG) in derived TSC lines. C, RT-qPCR confirming the loss of Fgfr1 mRNA in Fgfr1−/− TSCs and showing unchanged Fgfr2 levels. D, Immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR, showing unchanged E-Cadherin protein expression and mRNA levels in control and mutant TSCs. E, RT-qPCR for TSCs markers showing no significant changes in Fgfr1−/− compared to wild type TSCs. F, RT-qPCR showing significantly lower expression of TE lineage markers in differentiated Fgfr1−/− compared to wild type TSCs. C-F: graphs represent three individually derived wild type TSC lines and three individually derived Fgfr1−/− TSC lines. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Figure 5. Fgfr1−/− TSCs differentiation is impaired.

A, brightfield images, showing that wild type and Fgfr1−/− TSCs become larger and less dense upon FGF removal for two days. No morphological differences can be detected between wild type and mutant cells. B, mRNA levels of TSC markers are downregulated equally in wild type and Fgfr1−/− TSCs. C, TE lineage markers are not upregulated to the same extent in Fgfr1−/− TSCs compared to wild type. B and C: Graphs represent technical triplicates of the same TSC line. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− blastocyst show reduced numbers of TE and double null TSCs are not viable.

We next attempted to derive Fgfr2−/− TSC lines from Fgfr2+/− intercrosses. Fgfr2−/− embryos die at E10.5 and show defects in the labyrinthine layer of the placenta, a derivative of the TE (Molotkov et al., 2017; Xu et al., 1998; Yu et al., 2003). We were able to derive Fgfr2−/− TSCs, in agreement with the late Fgfr2−/− phenotype. From four blastocyst outgrowths, two were Fgfr2−/−, one Fgfr2+/− and one Fgfr2+/+ (Figure S1A). The morphology of Fgfr2−/− TSCs was comparable to wild type lines (Figure S1B) and the cells showed normal levels of Cdx2 mRNA (Figure S1C). After 72h and 96h without FGF, Fgfr2−/− TSCs downregulated TSC markers and upregulated TE lineage markers (Figure S1D, E). These results show that TSCs can be established and differentiated in the absence of FGFR2.

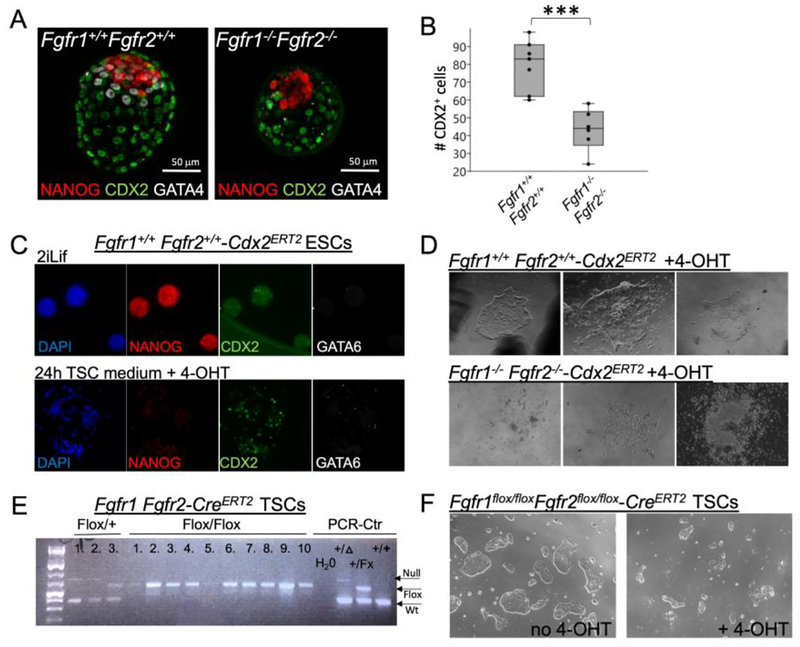

Next, we analyzed Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− embryos, which fail to develop past E4.5 (Kang, et al. 2017; Molotkov et al. 2017). We had previously demonstrated that double mutant embryos are smaller than wild-type embryos, but that they had a similar number of ICM cells (Molotkov et al., 2017), suggesting that the size reduction is due to a deficiency in TE development. We cultured E3.5 embryos for 48h (Figure 6A, B) and counted the number of CDX2+ TE cells. The number of CDX2+ TE cells in Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− blastocyst was nearly half the level of Fgfr1+/+ Fgfr2+/+ blastocysts (Figure 6B). This demonstrate that TE development is compromised in Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− mutants.

Figure 6. Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− embryos show reduced TE, and TSCs cannot be obtained from CDX2 overexpressing Fgfr1−/−Fgfr2−/− ESCs or deleted from Fgfr1flox/flox Fgfr2flox/flox TSCs.

A and B, Optical section images of Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− embryos isolated at E3.5 and cultured for 48h show reduced numbers of CDX2 positive TE cells. Seven Fgfr1+/+Fgfr2+/+ and six Fgfr1−/−Fgfr2−/− embryos were quantified, *** P < 0.001. C, Maximal projection images showing Fgfr1+/+-Cdx2ERT2 puromycin resistant clones expressing CDX2 and downregulating NANOG upon 24 hours of 4-OHT treatment. GATA6 is not expressed. D, brightfield images, showing three representative images for each genotype. Seven out of eight Fgfr1+/+Fgfr2+/+-Cdx2ERT2 ESC clones gave rise to TSC colonies, but none out of six Fgfr1−/−Fgfr2−/−-Cdx2ERT2 ESC clones gave rise to TSC colonies after two weeks in TSC medium with 1μg/ml 4-OHT. E, PCR results of genomic DNA showing that two out of three Fgfr1flox/+Fgfr2flox/+-CreERT2 TSC clones exhibit CRE recombination after induction with 4-OHT. Fgfr1flox/flox Fgfr2flox/flox-CreERT2 TSC colonies that escaped cell death did not undergo CRE recombination. F, Brightfield images showing 4-OHT treated Fgfr1flox/flox Fgfr2flox/flox-CreERT2 cultures exhibiting cell death.

We next attempted to derive Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− double mutant TSCs. Because of the low frequency (1/16) of double mutants from double heterozygous intercrosses, we approached this by trying to convert Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− ESCs (Molotkov et al., 2017) into TSCs by CDX2 overexpression (Niwa et al., 2005). Control and Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− ESCs were stably transfected with a 4-OHT inducible Cdx2 vector (Niwa et al. 2005). CDX2 expression was successfully induced with 4-OHT in TSC medium and ESCs downregulated the pluripotency marker NANOG; as expected, the PrE marker GATA6 was not detectable before or after 4-OHT treatment (Figure 6C). Seven TSC clones were obtained from eight wild type transfected ESC lines (Figure 6D). In contrast, none of six transfected Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− lines gave rise to TSC colonies (Figure 6D).

To independently validate these results, we derived Fgfr1flox/+Fgfr2flox/+ and Fgfr1flox/floxFgfr2flox/flox TSCs from blastocysts. We transiently transfected both lines with a Cre-IRES-Blasticidin vector. We assessed CRE activity by PCR of the recombined Fgfr2 locus. After a short blasticidin selection, we observed CRE recombination in four out of eleven double heterozygous lines. In contrast none out of thirty-one double homozygous lines showed recombination (data not shown). In parallel, we stably transfected both cell lines with a CreERT2-IRES-Blasticidin vector. Blasticidin-resistant clones were expanded and Cre presence was confirmed by PCR. Two out of three heterozygous control lines showed CRE recombination after 4-OHT administration (Figure 6E). Fgfr1flox/flox Fgfr2flox/flox cultures, however, exhibited high cell death as evidenced by increased numbers of floating cells (Figure 6F). Of the ten Fgfr1flox/floxFgfr2flox/flox TSC clones that nevertheless could be picked, none showed evidence for CRE induced DNA recombination (Figure 6E). Taken together, these results show that even though TSCs can tolerate the absence of one or the other FGFR, the loss of both FGFR1 and FGFR2 does not allow TSCs to be maintained and propagated.

Discussion

FGFR1 is known to play a critical role at gastrulation (Deng et al., 1994; Yamaguchi et al., 1994) but a number of Fgfr1−/− mutants fail to progress past implantation, an effect most marked on the co-isogenic 129 genetic background (Brewer et al., 2015; Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017). Loss of both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 leads to the complete absence of PrE development, with Fgfr1 playing the predominant role, which may contribute to early postimplantation failure. FGFR1 also plays a role in regulating various stages of EPI differentiation (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017). However, it is unlikely that PrE or EPI deficiency alone could explain the failure for mutant embryos to progress through the peri-implantation stage (Jedrusik et al., 2015). Indeed, chimeric embryos derived from Fgfr1−/− ES cells and wild type tetraploid embryos successfully implant, but later exhibit defects in mesoderm formation (Ciruna et al., 1997). This further supports the notion that FGF signaling is important for extraembryonic lineage development. In this work, we have identified a defect in TE development in Fgfr1−/− and Fgfr1−/− Fgfr2−/− embryos, which might lead to failure at implantation.

During the compaction stage in preimplantation development, individual blastomeres undergo apicobasal polarization. Polarized cell divisions persist such that outside cells retain an apical side and remain at the surface while apolar cells adopt an internal position (Johnson and Ziomek 1981; further reviewed in (Stephenson et al., 2012; White et al., 2018). Cell polarization is thus critical for normal development, and Cdh1−/− mutants lacking both maternal and zygotic E-Cadherin expression exhibit abnormal morphology of TE cells (Stephenson et al., 2010). We observed that Fgfr1−/− blastocysts show altered E-Cadherin polarized expression in TE cells, with strong basal expression, very similar to the phenotype observed in Cdx2−/− mutants (Strumpf et al., 2005). In intestinal epithelial cells, CDX2 enhances trafficking of E-Cadherin to the cell membrane (Funakoshi et al., 2010), whereas conditional loss of Cdx2 leads to a strikingly similar alteration in E-Cadherin polarization as we have observed (Gao and Kaestner, 2010). Taken together, these observations suggest that CDX2 levels have to be maintained at specific levels to ensure proper apicobasal polarity. A connection between Fgfr1 and Cdh1 expression has been made previously, as Fgfr1−/− embryos on a mixed genetic background fail to downregulate E-Cadherin and complete EMT at the primitive streak (Ciruna and Rossant, 2001). Moreover, it has been shown recently that FGF signaling in Drosophila controls EMT by regulating apicobasal polarity, as Heartless (Fgfr) mutants exhibit reduced numbers of adherens junctions and defects in mesodermal cell polarity (Sun and Stathopoulos, 2018). These observations raise the additional possibility that elevated Cdh1 expression in Fgfr1−/− TE cells may interfere with subsequent EMT associated with later stages of TE cell differentiation.

Fgfr1−/− mutants maintained CDX2 expression in the mural TE, similar to Cdh1−/− mutants. CDX2 is highly expressed in the mural TE at E3.5, and is then downregulated by the time of implantation. The significance of CDX2 expression in the mural TE cells at E3.5 remains unexplored, however, it may be required to inhibit OCT4 and NANOG expression as it does at the morula stage (Blij et al., 2012; Jedrusik et al., 2015; Strumpf et al., 2005). Moreover, CDX2 has been shown to directly interact with OCT4 to suppress its transcriptional activity in TE cells (Niwa et al., 2005). Last, as a proepithelial factor, CDX2 may be regulating TE fate both through Nanog and Oct4 inhibition as well as promoting Eomes and Elf5 expression. It may also allow junction formation that supports blastocoel establishment and maintenance. At a later stage CDX2 would need to be downregulated to reduce epithelial protein expression and to allow for protrusive activity and partial EMT required for implantation (Sutherland, 2003). It is therefore possible that maintained Cdx2 expression in TE cells prevents Fgfr1−/− embryos from initiating the differentiation program required for implantation.

The polar TE forms the extra-embryonic ectoderm while maintaining a pool of proliferative TSCs (Tanaka et al., 1998). It lies in close proximity with the FGF4 producing EPI, whereas the mural TE, which lines the blastocoel cavity, undergoes differentiation into giant cells and initiates implantation. Further studies will be required to determine if FGFR1/2 indeed acts autonomously within the TE, or if the effects we observed are an indirect effect of a defect in EPI maturation or PrE development. FGF4 is also essential for maintaining TSCs proliferation and potency (Simmons and Cross, 2005; Tanaka et al., 1998). Upon removal of FGF4, TSCs differentiate into various TE lineages. We show that loss of either FGFR1 or FGFR2 does not impact the ability to establish or maintain TSCs. This may be due to the fact that both receptors are expressed in TSCs and the presence of one or the other receptor is sufficient for maintaining these cultures. Neither FGFR1 nor FGFR2 are required for the downregulation of TSC markers. However, Fgfr1−/− TSCs fail to upregulate TE differentiation markers upon FGF4 removal to the same extent as wild type cells. In contrast to the in vivo situation, Fgfr1−/− TSCs were able to downregulate Cdx2. However, we were unable to fully differentiate Fgfr1−/− TSCs into labyrinthine cells, spongiotrophoblast cells or trophoblast giant cells, the first TE lineage to be specified from proliferating TSCs in vivo. The elimination of both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 led to a reduction in the number of TE cells in embryos, and we were unable to isolate double mutant TSCs, using two different approaches. Taken together, these results highlight a critical role for FGF signaling, in particular FGFR1, in TE development and TSC maintenance. Furthermore, they uncover an unsuspected requirement for FGFR1 signaling during trophoblast differentiation, which may be an important contributory factor in early pregnancy failure.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Fgfr2−/− TSCs can be derived and show no defects in differentiation. A, PCR to detect the genotype of the obtained TSC lines. B, Brightfield images of Fgfr2−/− TSCs, exhibiting normal morphology. C, RT-qPCR showing that Fgfr2−/− TSCs express Cdx2 mRNA equal to control cells. D, Upon FGF removal for 72h and 96h, TSC markers are downregulated (E) and TE lineage markers are up-regulated in Fgfr2−/− TSCs. Two individually derived TSC lines are represented by each graph.

Highlights.

Fgfr1−/− embryos fail to downregulate Cdx2 in the mural trophectoderm.

Fgfr1−/− trophectoderm cells exhibit abnormal apicobasal E-Cadherin polarity.

TSCs from Fgfr1−/− or Fgfr2−/− mutants, but not double mutants, can be isolated and maintained.

Fgfr1−/− TSCs fail to efficiently express TE differentiation markers upon differentiation.

Taken together, these results highlight the role for FGF signaling in trophectoderm development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rob Krauss, Carla Mulas, Jenny Nichols and our laboratory colleagues for helpful discussions and for critical comments on the manuscript, and Austin Smith and Ken Jones for vectors. This work was supported in part by the Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai (P30 CA196521 Cancer Center Support Grant) and by grants from NYSTEM (IIRP N11G-131) and NIH/NIDCR (RO1 DE022778) to P.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Betschinger J, Nichols J, Dietmann S, Corrin PD, Paddison PJ, Smith A, 2013. Exit from pluripotency is gated by intracellular redistribution of the bHLH transcription factor Tfe3. Cell 153, 335–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blij S, Frum T, Akyol A, Fearon E, Ralston A, 2012. Maternal Cdx2 is dispensable for mouse development. Development 139, 3969–3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JR, Mazot P, Soriano P, 2016. Genetic insights into the mechanisms of Fgf signaling. Genes Dev 30, 751–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JR, Molotkov A, Mazot P, Hoch RV, Soriano P, 2015. Fgfr1 regulates development through the combinatorial use of signaling proteins. Genes Dev 29, 18631874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazaud C, Yamanaka Y, Pawson T, Rossant J, 2006. Early lineage segregation between epiblast and primitive endoderm in mouse blastocysts through the Grb2-MAPK pathway. Dev Cell 10, 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruna B, Rossant J, 2001. FGF signaling regulates mesoderm cell fate specification and morphogenetic movement at the primitive streak. Dev Cell 1, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruna BG, Schwartz L, Harpal K, Yamaguchi TP, Rossant J, 1997. Chimeric analysis of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (Fgfr1) function: a role for FGFR1 in morphogenetic movement through the primitive streak. Development 124, 2829–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W, Taub DD, Gardner K, 2007. qPrimerDepot: a primer database for quantitative real time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 35, D805–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng CX, Wynshaw-Boris A, Shen MM, Daugherty C, Ornitz DM, Leder P, 1994. Murine FGFR-1 is required for early postimplantation growth and axial organization. Genes Dev 8, 3045–3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B, Poueymirou W, Papaioannou VE, DeChiara TM, Goldfarb M, 1995. Requirement of FGF-4 for postimplantation mouse development. Science 267, 246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TP, Garrod DR, Elsmore AJ, 1991. Desmosome biogenesis in the mouse preimplantation embryo. Development 112, 527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TP, Johnson MH, 1988. From egg to epithelium. Annu Rev Cell Biol 4, 459485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi S, Kong J, Crissey MA, Dang L, Dang D, Lynch JP, 2010. Intestinespecific transcription factor Cdx2 induces E-cadherin function by enhancing the trafficking of E-cadherin to the cell membrane. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299, G1054–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao N, Kaestner KH, 2010. Cdx2 regulates endo-lysosomal function and epithelial cell polarity. Genes Dev 24, 1295–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin SN, Papaioannou VE, 2003. Paracrine action of FGF4 during periimplantation development maintains trophectoderm and primitive endoderm. Genesis 36, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD, 2001. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano N, Mori Y, Oh-hora M, Kosugi A, Fujikawa T, Nakai N, Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Hamaoka T, Ogata M, 2003. Essential role for ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in placental development. Genes Cells 8, 847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch RV, Soriano P, 2006. Context-specific requirements for Fgfr1 signaling through Frs2 and Frs3 during mouse development. Development 133, 663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrusik A, Cox A, Wicher KB, Glover DM, Zernicka-Goetz M, 2015. Maternalzygotic knockout reveals a critical role of Cdx2 in the morula to blastocyst transition. Dev Biol 398, 147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Garg V, Hadjantonakis AK, 2017. Lineage Establishment and Progression within the Inner Cell Mass of the Mouse Blastocyst Requires FGFR1 and FGFR2. Dev Cell 41, 496–510e495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Piliszek A, Artus J, Hadjantonakis AK, 2013. FGF4 is required for lineage restriction and salt-and-pepper distribution of primitive endoderm factors but not their initial expression in the mouse. Development 140, 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunath T, Saba-El-Leil MK, Almousailleakh M, Wray J, Meloche S, Smith A, 2007. FGF stimulation of the Erk1/2 signalling cascade triggers transition of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from self-renewal to lineage commitment. Development 134, 2895–2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molotkov A, Mazot P, Brewer JR, Cinalli RM, Soriano P, 2017. Distinct Requirements for Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 in Primitive Endoderm Development and Exit from Pluripotency. Developmental Cell 41, 511–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molotkov A, Soriano P, 2018. Distinct mechanisms for PDGF and FGF signaling in primitive endoderm development. Dev Biol 442, 155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulas C, Kalkan T, Smith A, 2017. NODAL Secures Pluripotency upon Embryonic Stem Cell Progression from the Ground State. Stem Cell Reports 9, 77–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J, Silva J, Roode M, Smith A, 2009. Suppression of Erk signalling promotes ground state pluripotency in the mouse embryo. Development 136, 32153222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, Strumpf D, Takahashi K, Yagi R, Rossant J, 2005. Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell 123, 917–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohinata Y, Tsukiyama T, 2014. Establishment of trophoblast stem cells under defined culture conditions in mice. PLoS One 9, e107308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SH, Guy GR, Hadari YR, Laks S, Gotoh N, Schlessinger J, Lax I, 2000. FRS2 proteins recruit intracellular signaling pathways by binding to diverse targets on fibroblast growth factor and nerve growth factor receptors. Mol Cell Biol 20, 979–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba-El-Leil MK, Vella FD, Vernay B, Voisin L, Chen L, Labrecque N, Ang SL, Meloche S, 2003. An essential function of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Erk2 in mouse trophoblast development. EMBO Rep 4, 964–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DG, Cross JC, 2005. Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol 284, 12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson RO, Rossant J, Tam PP, 2012. Intercellular interactions, position, and polarity in establishing blastocyst cell lineages and embryonic axes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson RO, Yamanaka Y, Rossant J, 2010. Disorganized epithelial polarity and excess trophectoderm cell fate in preimplantation embryos lacking E-cadherin. Development 137, 3383–3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumpf D, Mao CA, Yamanaka Y, Ralston A, Chawengsaksophak K, Beck F, Rossant J, 2005. Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development 132, 2093–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Stathopoulos A, 2018. FGF controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions during gastrulation by regulating cell division and apicobasal polarity. Development 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland A, 2003. Mechanisms of implantation in the mouse: differentiation and functional importance of trophoblast giant cell behavior. Dev Biol 258, 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Soriano P, 2000. Epiblast-restricted Cre expression in MORE mice: a tool to distinguish embryonic vs. extra-embryonic gene function. Genesis 26, 113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J, 1998. Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science 282, 2072–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MD, Zenker J, Bissiere S, Plachta N, 2018. Instructions for Assembling the Early Mammalian Embryo. Dev Cell 45, 667–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Weinstein M, Li C, Naski M, Cohen RI, Ornitz DM, Leder P, Deng C, 1998. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2)-mediated reciprocal regulation loop between FGF8 and FGF10 is essential for limb induction. Development 125, 753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi TP, Harpal K, Henkemeyer M, Rossant J, 1994. fgfr-1 is required for embryonic growth and mesodermal patterning during mouse gastrulation. Genes Dev 8, 3032–3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka Y, Lanner F, Rossant J, 2010. FGF signal-dependent segregation of primitive endoderm and epiblast in the mouse blastocyst. Development 137, 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, Towler DA, Ornitz DM, 2003. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development 130, 3063–3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Fgfr2−/− TSCs can be derived and show no defects in differentiation. A, PCR to detect the genotype of the obtained TSC lines. B, Brightfield images of Fgfr2−/− TSCs, exhibiting normal morphology. C, RT-qPCR showing that Fgfr2−/− TSCs express Cdx2 mRNA equal to control cells. D, Upon FGF removal for 72h and 96h, TSC markers are downregulated (E) and TE lineage markers are up-regulated in Fgfr2−/− TSCs. Two individually derived TSC lines are represented by each graph.