Abstract

Purpose

Advances in germline genetics, and related therapeutic opportunities, present new opportunities and challenges in prostate cancer. The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium Germline Genetics Working Group was established to address genetic testing for men with prostate cancer, especially those with advanced disease undergoing testing for treatment-related objectives and clinical trials.

Methods

The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium Germline Genetics Working Group met monthly to discuss the current state of genetic testing of men with prostate cancer for therapeutic or clinical trial purposes. We assessed current institutional practices, developed a framework to address unique challenges in this population, and identified areas of future research.

Results

Genetic testing practices in men with prostate cancer vary across institutions; however, there were several areas of agreement. The group recognized the clinical benefits of expanding germline genetic testing, beyond cancer risk assessment, for the goal of treatment selection or clinical trial eligibility determination. Genetic testing for treatment selection should ensure patients receive appropriate pretest education and consent and occur under auspices of a research study whenever feasible. Providers offering genetic testing should be able to interpret results and recommend post-test genetic counseling for patients. When performing tumor (somatic) genomic profiling, providers should discuss the potential for uncovering germline mutations and recommend appropriate genetic counseling. In addition, family members may benefit from cascade testing and early cancer screening and prevention strategies.

Conclusion

As germline genetic testing is incorporated into practice, further development is needed in establishing prompt testing for time-sensitive treatment decisions, integrating cascade testing for family, ensuring equitable access to testing, and elucidating the role of less-characterized germline DNA damage repair genes, individual gene-level biologic consequences, and treatment response prediction in advanced disease.

INTRODUCTION

Although the contribution of heredity to prostate cancer has long been known, the underlying genetic causes remained elusive. Recent discoveries reveal that a significant fraction of men with metastatic prostate cancer (mPC) carry germline mutations in DNA damage repair (DDR) genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM.1,2 Compelling early findings suggest that germline and/or somatic alterations in these and other DDR genes may predict response to poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and platinum chemotherapy.3-5 Germline mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2), which are associated with Lynch syndrome and development of tumors with defective DNA MMR or high microsatellite instability (MSI), may identify candidates for immunotherapy with programmed cell death protein 1 checkpoint inhibitors.6 In addition, response to other systemic therapies for prostate cancer may be influenced by the presence of a germline and/or somatic DDR gene mutation.7-10

The current models for genetic counseling and testing were developed for assessment of individuals and families with suspicion for hereditary cancer syndromes and focused on risk assessment, cancer screening, and risk reduction (eg, salpingo-oophorectomy for female BRCA1/2 carriers). For prostate cancer, genetic counseling and testing practices are newly driven by a growing interest in identifying patients who are candidates for enrollment in biomarker-selected clinical trials. This treatment-driven ascertainment, where patients are referred for germline testing in part for therapy selection, presents unique opportunities and challenges for practitioners regarding appropriate delivery of elements of genetic counseling in a feasible manner.

The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium is a group of researchers from 11 institutions working together to develop novel therapeutics and biomarkers, translating scientific discoveries to improve standards of care in prostate cancer. The Germline Genetics Working Group of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium was established in June of 2017 in response to the growing intersection between germline genetics and therapeutics. In this article, we outline the special considerations when genetic testing is used for therapeutic purposes in men with mPC and to suggest areas of future research. Although germline genetics may affect management decisions in early-stage prostate cancer, we focus here on advanced disease because of the current therapeutic and clinical trial implications, although many of the principles outlined apply to all stages of disease.

GERMLINE DNA REPAIR MUTATIONS IN RECURRENT AND METASTATIC PROSTATE CANCER

Prostate cancer has a significant heritable component, with 57% of the risk attributed to genetic factors.11,12 Mutations in high and moderately penetrant genes involved in DDR can be associated with varying degrees of increased predisposition to prostate cancer (Appendix Table A1). In a landmark study, the incidence of inherited pathogenic DDR mutations in men with mPC was 11.8% (5.3% with mutations in BRCA2, 1.9% in CHEK2, and 1.5% in ATM).1 This prevalence was significantly higher compared with men with localized prostate cancer (11.8% v 4.6%; P < .001). In a second confirmatory study, the prevalence of germline pathogenic DDR mutations in unselected patients with recurrent or mPC was 14.0% (6.0% in BRCA2, 2.0% in CHEK2, and 2.0% in ATM), with an apparent enrichment in men with intraductal or ductal histologic features.13 An association between germline BRCA2 mutations and intraductal prostate cancer was also reported in a prior study.14

Germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers may have more aggressive disease at presentation and have a higher risk of recurrence and prostate cancer–specific mortality compared with noncarriers.15-17 In a retrospective case-case study of patients with low-risk localized prostate cancer and patients who died as a result of disease, the combined carrier rate of BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM mutations was higher in lethal cases (6.1% v 1.4%; P < .001), and those with mutations had a shorter interval to death after diagnosis.18

Men with Lynch syndrome (due to germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2) may also be at increased risk of prostate cancer; however, data are conflicting, with some studies showing a two- to five-fold increased risk and others showing no increased risk.19-23 These risk ranges may be due to the different penetrance of Lynch genes; there is suggestion that prostate cancer risk is particularly elevated in MSH2 carriers.24,25 It is also likely that as screening for colorectal cancer improves, men with Lynch syndrome are living longer, and thus the incidence of older-onset cancers is increasing.25 Unfortunately, many patients with prostate cancer with germline MMR mutations do not meet traditional family history criteria.26 In men with Lynch syndrome, prostate cancer infrequently represents the index cancer; however, prostate tumors can lack MMR gene protein expression or show MSI.21,27 In a study of 451 patients with prostate cancer, 3% of patients had tumors with somatic alterations in MMR genes, which predicted for high mutation count.28 Identifying patients with mPC whose tumors harbor these features has become increasingly relevant, because the programmed cell death protein 1 immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of any cancer with deficient MMR or high MSI.29

CLINICAL TRIALS USING GERMLINE MUTATIONS AS ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

An increasing number of therapeutic clinical trials in prostate cancer are using presence of DDR mutations, including germline, as an eligibility requirement for enrollment, similar to advanced ovarian and breast cancers with germline BRCA1/2 mutations (eg, olaparib, rucaparib; Table 1). For example, the BRCAaway trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03012321) is a phase II randomized trial of the PARP inhibitor olaparib versus abiraterone versus the combination of the two agents in men with germline or somatic homologous recombination deficiency mutations. Additional trials are exploring the efficacy of rucaparib, niraparib, and olaparib as single agent for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and a deleterious genomic alteration, either germline or somatic, in BRCA2, BRCA1, and other DDR genes (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02952534, NCT02975934, NCT02854436, NCT02987543). The TRIUMPH (Trial of Rucaparib in Patients With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Harboring Germline DNA Repair Gene Mutations) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03413995) will enroll men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer and a germline DDR gene pathogenic alteration, who will be treated with the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in the absence of hormonal therapy. It is anticipated that an increasing number of men with mPC will undergo genetic testing and that new trials will be designed and implemented for the germline DDR-deficient population.

Table 1.

Selected Therapeutic Clinical Trials in Prostate Cancer With Relevance to Germline Genetics

CONTEXTUAL DIFFERENCES AND IMPORTANCE OF CONFIRMING PATIENT PRIORITIES

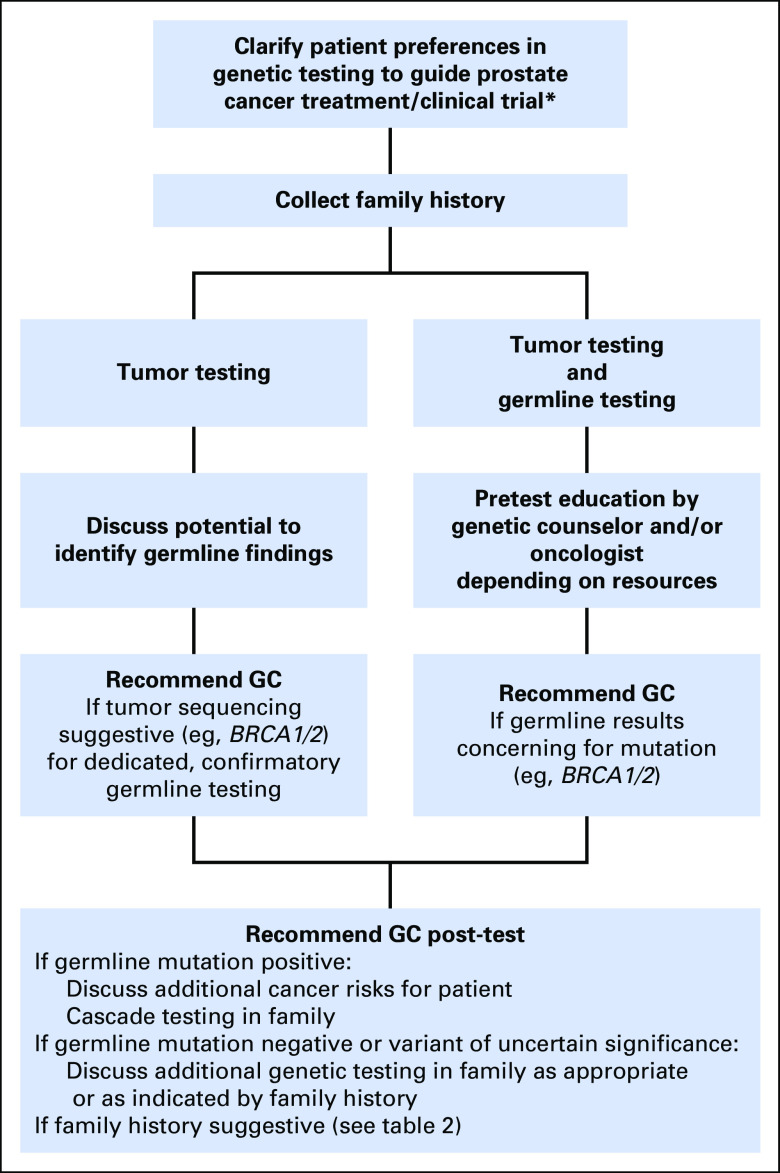

Next-generation sequencing has made germline testing more accessible and comprehensive, and broader cohorts of patients with cancer are being tested using large gene panels. These approaches have the potential to address two important but distinct objectives: first, treatment and clinical trial possibilities, and, second, inherited cancer risk. For providers, it is worth discussing and confirming patient goals before offering testing—for example, asking whether patients are interested primarily in treatment options, familial risk assessment, or both. Figure 1 provides a framework for genetic testing within the context of treatment decisions. Oncologist-driven genetic education is ideally in close collaboration with a cancer genetics service. Family history intake is critical and needs to be streamlined for oncology and clinical trial settings. Table 2 summarizes clinical criteria to consider for referral to genetic counseling.

Fig 1.

Framework for approaching genetic testing within the context of therapeutic decisions. (*) Currently primarily relevant to metastatic and high-risk localized prostate cancer, but likely will include earlier disease states in the future. GC, genetic counseling.

Table 2.

Referral Criteria for Genetic Counseling for Men with Prostate Cancer

This panel agrees that men with prostate cancer who undergo germline genetic testing for therapeutic or clinical trial options should receive pretest education on the implications of a positive result for themselves and for their families. Which genes should be included in testing may vary if the setting is treatment decision making versus risk assessment and risk management. For example, although at least BRCA1/2 and MMR genes should be tested for men who meet criteria for the corresponding syndromes, additional genes, such as ATM, CHEK2, and PALB2, could be included for therapeutic decision making, especially in the clinical trial setting.4,30,31

TUMOR-ONLY SEQUENCING MAY IDENTIFY GERMLINE MUTATIONS

Targeted next-generation sequencing of the tumor is also increasingly being used for treatment decision making and clinical trial eligibility determination. Although the goal of testing may be to identify treatment options, there is a possibility that somatic testing may identify germline mutations that are reflected in tumor sequence. In several recent studies of research somatic sequencing, germline mutations with clinical implications were identified.32,33 Tumor sequencing may even be more sensitive in detecting genetic syndromes, such as Lynch, than the traditional molecular tests.34

Most commercial tumor assays do not specifically report whether a mutation is present in the germline, and some subtract the germline component, but the presence of well-described founder mutations may be highly suggestive. For example, the Ashkenazi Jewish BRCA1/2 founder mutations (BRCA1 185delAG; BRCA1 5382insC; BRCA2 6174delT) are almost always germline, not somatic, events, and ordering providers should be familiar with them. Somatic tumor profiling can also identify increased mutation load and MSI, which can be associated with germline MMR mutations (Lynch syndrome).35

Although it seems that most patients are interested in knowing secondary germline findings, they also expect their providers to offer decision-making guidance and clarify key information.36,37 This panel agrees that men with prostate cancer who undergo tumor-based genetic testing for therapeutic or clinical trial options should be educated about the potential for uncovering germline mutations, which may warrant referral to a cancer genetic specialist for confirmatory germline testing. This panel recommends that if a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation is identified on tumor-based testing, patients should be referred for discussion of dedicated, confirmatory germline testing. Moreover, if increased mutational load, a high MSI, or MMR deficiency is identified in tumor-only profiling, the patient’s family history and personal history of other malignancies should be confirmed and reviewed with consideration for referral for dedicated confirmatory germline testing.

NEED FOR NEW GENETICS CARE DELIVERY MODELS

A major challenge is how best to integrate the workflow and provide the clinical support needed for responsible genetics care. The traditional clinical genetics cancer care delivery model—where patients are referred to a genetic counselor for in-person, pretest risk assessment and education and in-person post-test counseling—cannot meet the projected demand for testing of patients with prostate cancer, some facing time-sensitive treatment decisions. Even when testing is performed primarily for treatment selection, building in systems for those who are interested in testing of family members is of critical importance.

Current barriers to genetic testing have been described in the context of testing for cancer predisposition in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and Lynch syndromes. These barriers include process issues (referral to genetic counseling and testing, access, wait times, insurance coverage); physician knowledge, comfort, and time; patients’ lack of awareness and understanding; and refusal of testing. With appropriate education, patients may be more interested in pursuing testing. For example, > 85% of patients with ovarian cancer reported willingness to be tested if there were therapeutic implications or benefit to family, and a majority believed that genetic testing should be offered before or at the time of diagnosis.38

When testing for therapeutic decision making, the ability to undergo assessment and testing and receive results in a timely manner is of utmost importance. Newer approaches in cancer risk genetics include video- or phone-based pretest counseling and mainstreaming, an approach in which trained individuals provide standardized consenting and counseling before testing and genetics referral.39 The ENGAGE (Evaluation of a Streamlined Oncologist-Led BRCA Mutation Testing and Counseling Model for Patients With Ovarian Cancer) study of oncologist-led BRCA1/2 mutation testing in women with ovarian cancer showed that this process is feasible, with high patient satisfaction.40 These alternate genetic counseling delivery approaches need to be studied for provider feasibility and patient acceptability. Several trials at our sites are seeking to explore some of these new delivery models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Trials Testing Novel Approaches to Genetic Testing

SPECIAL CHALLENGES IN UNDERSERVED POPULATIONS

Intensive efforts are needed to ensure that genetic assessment is available to underserved populations, which include ethnic and racial minorities, people of low income, and those in rural areas, among others.41,42 Although rates of germline testing have not been studied in different ethnic and racial subgroups of men with prostate cancer, evidence shows that black and Hispanic women with breast cancer are substantially less likely to undergo genetic testing.43,44 Reasons for disparities in genetic testing may include differences in physician referrals, distrust and/or lack of understanding of genetics and cancer risk, fear of genetic discrimination on the part of insurers, and disproportionate financial and time burdens for patients with limited resources.44-50 Ensuring equitable access to genetic testing for black men with prostate cancer may be particularly important, because some preliminary studies show they may be more likely to have germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 than white men.51 This is compounded by the fact that black men have a 2.4 times greater risk of death from prostate cancer, are more likely to present with late-stage disease, and are significantly less likely to receive definitive treatment than non-Hispanic white men.52-55

Improving access to genetic testing in geographically remote areas, where availability of genetic counselors is scare, is also an active area of research. Telephone genetic consults, and other novel genetic assessment, education, and testing delivery methods, show promise.56 To expand our knowledge and evidence of most effective testing strategies, men with prostate cancer should be offered genetic testing in the setting of clinical trials whenever feasible.

THE CRUCIAL RESPONSIBILITY OF CASCADE TESTING

Cascade testing is the systematic identification of individuals at risk for a hereditary condition through extension of genetic testing to biologic relatives. Although awareness of cascade testing is important in any situation where a germline mutation is identified, it can be particularly important when genetic testing is performed for therapeutic selection. In contrast to patients who pursue genetic testing because of familial cancer risk, those who undergo germline testing for therapy selection may be less aware of the potential implications to family members, because they were not necessarily tested because of an identified familial risk. Moreover, men with prostate cancer are often diagnosed when their children are adults, can pursue testing, and, if positive, undergo enhanced cancer screening or risk-reduction strategies.

There are several known barriers for a patient’s communication of results to family members. In BRCA1/2 screening studies, factors associated with of lack of communication include high worry about genetic risks, low interest or understanding of genomic information, and negative family history.57-59 Men and second-degree relatives are less likely to pursue genetic testing.58 Thus, there is an opportunity through education to increase familial communication of results. This panel agrees that when germline testing is performed, the ordering provider should be knowledgeable and work with local cancer genetics experts to offer cascade testing for family members.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Recent exciting discoveries in prostate cancer genetics and potential therapeutic interventions with PARP inhibitors and platinum chemotherapies have led to a rapid increase in germline testing for men with mPC. The traditional framework for genetic testing was developed for individuals believed to be at risk for inherited syndromes, but this model requires adaptation for men with mPC who are increasingly referred for genetic testing to aid in treatment decisions. In this article, we have highlighted special considerations with this treatment-driven ascertainment approach and described areas of research needs (Tables 4 and 5). As the field rapidly evolves, close collaboration between oncologists, urologists, clinical geneticists and counselors, researchers, and indeed, patients themselves, among others, will ensure that we develop the best practices to benefit patients with mPC and their families.

Table 4.

Challenges and New Research Directions

Table 5.

Consensus Statements

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Mark Robson, MD, for his review and comments on this article.

Appendix

Table A1.

Selected Genes Associated With Treatment Implications and Predisposition to Prostate Cancer

Footnotes

Supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Prostate Cancer Research Program under Awards No. W81XWH-17-2-0043, W81XWH-17-2-0018, W81XWH-17-2-0017, W81XWH-17-2-0020, W81XWH-17-2-002, W81XWH-17-2-00221, W81XWH-17-2-0027, and W81XWH-15-2-0018, the Prostate Cancer Foundation (M.I.C., E.S.A., W.A., H.H.C.), the Institute for Prostate Cancer Research, the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer National Institutes of Health SPORE Grant No. CA097186, and National Cancer Institute Center Core Grant No. P30 CA008748.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Channing J. Paller, Wassim Abida, Joshi J. Alumkal, Daniel J. George, Celestia S. Higano, Akash Patnaik, Charles J. Ryan, Edward M. Schaeffer, Mary-Ellen Taplin, Noah D. Kauff, Jacob Vinson, Emmanuel S. Antonarakis, Heather H. Cheng

Collection and assembly of data: Maria I. Carlo, Veda N. Giri, Channing J. Paller, Tomasz M. Beer, Elisabeth I. Heath, Rana R. McKay, Mary-Ellen Taplin, Noah D. Kauff, Jacob Vinson, Emmanuel S. Antonarakis, Heather H. Cheng

Data analysis and interpretation: Maria I. Carlo, Veda N. Giri, Channing J. Paller, Joshi J. Alumkal, Tomasz M. Beer, Himisha Beltran, Daniel J. George, Elisabeth I. Heath, Rana R. McKay, Alicia K. Morgans, Akash Patnaik, Charles J. Ryan, Walter M. Stadler, Mary-Ellen Taplin, Noah D. Kauff, Jacob Vinson, Emmanuel S. Antonarakis

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/author-center.

Maria I. Carlo

No relationship to disclose

Veda N. Giri

No relationship to disclose

Channing J. Paller

Consulting or Advisory Role: Dendreon

Research Funding: Eli Lilly (Inst)

Wassim Abida

Honoraria: CARET

Consulting or Advisory Role: Clovis Oncology

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Zenith Epigenetics, Clovis Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GlaxoSmithKline

Joshi J. Alumkal

Consulting or Advisory Role: Astellas Pharma, Bayer AG, Janssen Biotech

Research Funding: Aragon Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Zenith Epigenetics (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst)

Tomasz M. Beer

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Salarius Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Clovis Oncology, Janssen Biotech, Janssen Oncology, Janssen Research & Development, Johnson & Johnson, Janssen Japan, Merck, Pfizer

Research Funding: Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb/Medarex (Inst), Janssen Research & Development (Inst), Medivation/Astellas (Inst), Oncogenex (Inst), Sotio (Inst), Sotio, Theraclone Sciences (Inst)

Himisha Beltran

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Oncology, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie

Research Funding: Astellas Pharma (Inst), Janssen (Inst), AbbVie/Stemcentrx, Eli Lilly (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Daniel J. George

Honoraria: Sanofi, Bayer, Exelixis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer AG, Exelixis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Astellas Pharma, Innocrin Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Myovant Sciences

Speakers' Bureau: Sanofi, Bayer, Exelixis

Research Funding: Exelixis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Acerta Pharma (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Dendreon (Inst), Innocrin Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Expert Testimony: Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bayer AG, Exelixis, Genentech, Medivation, Merck, Pfizer

Elisabeth I. Heath

Honoraria: Bayer, Dendreon, Sanofi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Agensys

Speakers' Bureau: Sanofi

Research Funding: Tokai Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Seattle Genetics (Inst), Agensys (Inst), Dendreon (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Celldex Therapeutics (Inst), Inovio Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Celgene (Inst)

Celestia S. Higano

Employment: CTI BioPharma (I)

Leadership: CTI BioPharma (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: CTI BioPharma (I)

Honoraria: Genentech

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer AG, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Orion, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Asana Biosciences, Endocyte, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Myriad Genetics, Tolmar, Janssen

Research Funding: Aragon Pharmaceuticals (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Dendreon (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Medivation (Inst), Emergent BioSolutions (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Roche (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bayer AG, Astellas Pharma, Clovis Oncology, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Endocyte, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Orion Pharma, Menarini, Myriad Genetics, Pfizer

Rana R. McKay

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen, Novartis

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Bayer AG (Inst)

Alicia K. Morgans

Honoraria: Genentech, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, AstraZeneca, Sanofi

Akash Patnaik

Honoraria: Clovis Oncology, Merck, Prime Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Oncology

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Progenics Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Clovis Oncology, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Prime Oncology, Janssen Oncology

Charles J. Ryan

Honoraria: Janssen Oncology, Astellas Pharma, Bayer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer AG, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: BIND Biosciences, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Novartis

Edward M. Schaeffer

Consulting or Advisory Role: OPKO Diagnostics, AbbVie

Walter M. Stadler

Honoraria: CVS Caremark, Sotio, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: CVS Caremark, Sotio, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Bayer AG, Pfizer, Clovis Oncology, Genentech

Research Funding: Bayer AG (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Genentech (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Medivation (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Merck (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Janssen (Inst), Johnson & Johnson (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), X4 Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Calithera Biosciences (Inst)

Other Relationship: UpToDate, American Cancer Society

Mary-Ellen Taplin

Honoraria: Janssen-Ortho, Clovis Oncology, Astellas Pharma, Incyte, UpToDate, Research to Practice

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen-Ortho, Bayer AG, Guidepoint Global, Best Doctors, UpToDate, Clovis Oncology, Research to Practice, Myovant Sciences, Incyte

Research Funding: Janssen-Ortho (Inst), Medivation (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Tokai Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Medivation, Janssen Oncology, Tokai Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharma, Incyte

Noah D. Kauff

No relationship to disclose

Jacob Vinson

No relationship to disclose

Emmanuel S. Antonarakis

Honoraria: Sanofi, Dendreon, Medivation, Janssen Biotech, ESSA Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sanofi, Dendreon, Medivation, Janssen Biotech, ESSA Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology

Research Funding: Janssen Biotech (Inst), Johnson & Johnson (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Dendreon (Inst), Aragon Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Tokai Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Constellation Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Co-inventor of a biomarker technology that has been licensed to Qiagen

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Dendreon, Medivation

Heather H. Cheng

Research Funding: Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Astellas Medivation, Janssen

REFERENCES

- 1.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing. JAMA. 2017;318:825–835. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomerantz MM, Spisák S, Jia L, et al. The association between germline BRCA2 variants and sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy among men with metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:3532–3539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng HH, Pritchard CC, Boyd T, et al. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in platinum-sensitive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;69:992–995. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweizer MT, Antonarakis ES. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of DNA repair gene mutations in advanced prostate cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2017;15:785–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teply BA, Antonarakis ES. Treatment strategies for DNA repair-deficient prostate cancer. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10:889–898. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1338138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Germline DNA-repair gene mutations and outcomes in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. Eur Urol . doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.035. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.035 [epub ahead of print on February 10, 2018] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Annala M, Struss WJ, Warner EW, et al. Treatment outcomes and tumor loss of heterozygosity in germline DNA repair-deficient prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;72:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, et al. Familial risk and heritability of cancer among twins in Nordic countries. JAMA. 2016;315:68–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute Genetics of Prostate Cancer (PDQ)–Health Professional Version. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/hp/prostate–genetics-pdq [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacsson Velho P, Silberstein JL, Markowski MC, et al. Intraductal/ductal histology and lymphovascular invasion are associated with germline DNA-repair gene mutations in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2018;78:401–407. doi: 10.1002/pros.23484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor RA, Fraser M, Livingstone J, et al. Germline BRCA2 mutations drive prostate cancers with distinct evolutionary trajectories. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13671. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro E, Goh C, Olmos D, et al. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1748–1757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro E, Goh C, Leongamornlert D, et al. Effect of BRCA mutations on metastatic relapse and cause-specific survival after radical treatment for localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher DJ, Gaudet MM, Pal P, et al. Germline BRCA mutations denote a clinicopathologic subset of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2115–2121. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Na R, Zheng SL, Han M, et al. Germline mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 distinguish risk for lethal and indolent prostate cancer and are associated with early age at death. Eur Urol. 2017;71:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowty JG, Win AK, Buchanan DD, et al. Cancer risks for MLH1 and MSH2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:490–497. doi: 10.1002/humu.22262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:214–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<214::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haraldsdottir S, Hampel H, Wei L, et al. Prostate cancer incidence in males with Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2014;16:553–557. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan S, Jenkins MA, Win AK. Risk of prostate cancer in Lynch syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:437–449. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond VM, Mukherjee B, Wang F, et al. Elevated risk of prostate cancer among men with Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1713–1718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel C, Loeffler M, Steinke V, et al. Risks of less common cancers in proven mutation carriers with Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4409–4415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Møller P, Seppälä TT, Bernstein I, et al. Cancer risk and survival in path_MMR carriers by gene and gender up to 75 years of age: A report from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Gut. 2018 ;67:1306–1316. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grindedal EM, Møller P, Eeles R, et al. Germ-line mutations in mismatch repair genes associated with prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2460–2467. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abida W, Armenia J, Gopalan A, et al. Prospective genomic profiling of prostate cancer across disease states reveals germline and somatic alterations that may affect clinical decision making. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00029. 10.1200/PO.17.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillessen S, Attard G, Beer TM, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: The report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference APCCC 2017. Eur Urol. 2018;73:178–211. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giri VN, Knudsen KE, Kelly WK, et al. Role of genetic testing for inherited prostate cancer risk: Philadelphia Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2017. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:414–424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng HH, Klemfuss N, Montgomery B, et al. A pilot study of clinical targeted next generation sequencing for prostate cancer: Consequences for treatment and genetic counseling. Prostate. 2016;76:1303–1311. doi: 10.1002/pros.23219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abida W, Armenia J, Gopalan A, et al. Prospective genomic profiling of prostate cancer across disease states reveals germline and somatic alterations that may affect clinical decision making. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00029. 10.1200/PO.17.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hampel H, Pearlman R, Beightol M, et al. Assessment of tumor sequencing as a replacement for Lynch syndrome screening and current molecular tests for patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:806–813. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Middha S, Zhang L, Nafa K, et al. Reliable pan-cancer microsatellite instability assessment by using targeted next-generation sequencing data. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00084. 10.1200/PO.17.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton JG, Shuk E, Genoff MC, et al. Interest and attitudes of patients with advanced cancer with regard to secondary germline findings from tumor genomic profiling. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e590–e601. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton JG, Shuk E, Garzon MG, et al. Decision-making preferences about secondary germline findings that arise from tumor genomic profiling among patients with advanced cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00182. 10.1200/PO.17.00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox E, McCuaig J, Demsky R, et al. The sooner the better: Genetic testing following ovarian cancer diagnosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.057. Erratum: Gynecol Oncol 145:409, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Percival N, George A, Gyertson J, et al. The integration of BRCA testing into oncology clinics. Br J Nurs. 2016;25:690–694. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.12.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colombo N, Huang G, Scambia G, et al. Evaluation of a streamlined oncologist-led BRCA mutation testing and counseling model for patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;36:1300–1307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawkins AK, Hayden MR. A grand challenge: Providing benefits of clinical genetics to those in need. Genet Med. 2011;13:197–200. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31820c056e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall MJ, Olopade OI. Disparities in genetic testing: Thinking outside the BRCA box. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2197–2203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.5889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones T, McCarthy AM, Kim Y, et al. Predictors of BRCA1/2 genetic testing among Black women with breast cancer: A population-based study. Cancer Med. 2017;6:1787–1798. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB, et al. Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: Black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genet Med. 2011;13:349–355. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182091ba4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allford A, Qureshi N, Barwell J, et al. What hinders minority ethnic access to cancer genetics services and what may help? Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:866–874. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong K, Calzone K, Stopfer J, et al. Factors associated with decisions about clinical BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1251–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Benkendorf J, et al. Ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about BRCA1 testing in women at increased risk. Patient Educ Couns. 1997;32:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shields AE, Burke W, Levy DE. Differential use of available genetic tests among primary care physicians in the United States: Results of a national survey. Genet Med. 2008;10:404–414. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181770184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson HS, Sussner K, Schwartz MD, et al. Receipt of genetic counseling recommendations among black women at high risk for BRCA mutations. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16:1257–1262. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vadaparampil ST, Wideroff L, Breen N, et al. The impact of acculturation on awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk among Hispanics in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:618–623. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrovics G, Ravindranath L, Chen Y, et al. Higher frequency of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in African American prostate cancer. J Urol. 2016;195:e548. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moses KA, Orom H, Brasel A, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in treatment for prostate cancer: Does cancer severity matter? Urology. 2017;99:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merrill RM, Lyon JL. Explaining the difference in prostate cancer mortality rates between white and black men in the United States. Urology. 2000;55:730–735. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paller CJ, Cole AP, Partin AW, et al. Risk factors for metastatic prostate cancer: A sentinel event case series. Prostate. 2017;77:1366–1372. doi: 10.1002/pros.23396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taksler GB, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Explaining racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. Cancer. 2012;118:4280–4289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, et al. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: A cluster randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju328. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elrick A, Ashida S, Ivanovich J, et al. Psychosocial and clinical factors associated with family communication of cancer genetic test results among women diagnosed with breast cancer at a young age. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-9995-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lieberman S, Lahad A, Tomer A, et al. Familial communication and cascade testing among relatives of BRCA population screening participants. Genet Med. doi: 10.1038/gim.2018.26. 10.1038/gim.2018.26 [Epub ahead of print March 29, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheung EL, Olson AD, Yu TM, et al. Communication of BRCA results and family testing in 1,103 high-risk women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2211–2219. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]