Abstract

Lumbar microlaminectomy is associated with shorter hospitalization and lower cost within the VA system.

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a common debilitating issue in older patients. Open laminectomies traditionally are the standard treatment for LSS; however, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has recently become a popular option to facilitate recovery and improve efficiency of care regarding spine procedures.

Guiot and colleagues described the technique for an MIS decompressive lumbar laminectomy procedure.1 The surgery may represent an important strategy to improve the efficiency of care for patients with severe LSS. Several authors have reported clinical benefits with the MIS lumbar laminectomy, leading to a significant improvement in the Oswetry Disability Index (ODI) 25 in the degenerative stenosis group in cases of LSS.2–5 In a recent review of 13 studies Wong and colleagues concluded that the MIS laminectomy was efficacious in terms of symptomatic relief and patient satisfaction for patients with LSS.6 Further, Rosen and colleagues found a significant improvement in the ODI scores and in the Short Form-36 body pain and physical functions scores in patients aged ≥ 75 years.7

Perioperative measures, including blood loss and narcotic consumption, have been shown to significantly decrease with MIS surgery compared with open decompression.8,9 Decreased narcotic use is of particular interest for the geriatric population because it is expected to allow those patients to remain more physically active and mentally agile.10

Also, long-term success is important when assessing the efficacy of new MIS procedures. Oertel and colleagues found that 85% of patients reported long-term success after unilateral laminotomy of bilateral decompression (ULBD).11 These results indicate that a MIS laminectomy is effective in older patients with LSS and neurogenic claudication.

Although there are numerous MIS approaches to alleviating LSS, more research is needed to determine whether it is superior to the open laminectomy.9,12,13 Skovrliand and colleagues reviewed publications comparing ULBD and open laminectomies and determined that currently insufficient evidence exists to define which technique leads to more positive outcomes.14 Thus, the purpose of this study is 2-fold. First, this study adds to the current research by comparing estimated blood loss and length of stay (LOS) for microscopic MIS laminectomy vs traditional laminectomy. Second, this study aims to address the difference in health care costs between the 2 types of surgery in the VHA.

The U.S. health care system is facing several challenges and in particular pressure for cost reduction.15 VA hospitals are not exempt from those challenges, and their operating budgets are influenced by political and economic factors.16 Because of those challenges, cost-effectiveness is gaining importance.7 Future decisions for procedure coverage and reimbursement rates are likely to consider ratios like the cost to quality-adjusted life-years (QALY). Improving this ratio requires a reduction of cost and/or an improvement in outcome.

Minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) may lower the cost of spine procedures. Wang and colleagues reported that minimally invasive posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) led to shorter stay and lower blood loss compared with traditional PLIF.17 These improvements led to about $8,000 in savings for a single-level PLIF.17

Lumbar degenerative disease is a frequently encountered condition, and lumbar laminectomy is one of the most frequently performed spine procedures at VA hospitals. Consequently, MISS may be an important strategy for the VA to face systematic challenges. At the Southern Arizona VA Health Care System (SAVAHCS) in Tucson, the authors converted lumbar laminectomies from traditional open surgery to a MIS procedure using a tubular retractor system and a paramedian approach. To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have evaluated outcomes and cost efficiency of MIS surgery at the VA. The results of such a study may be instrumental in choosing which surgery is appropriate in a patient-centered health care model.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

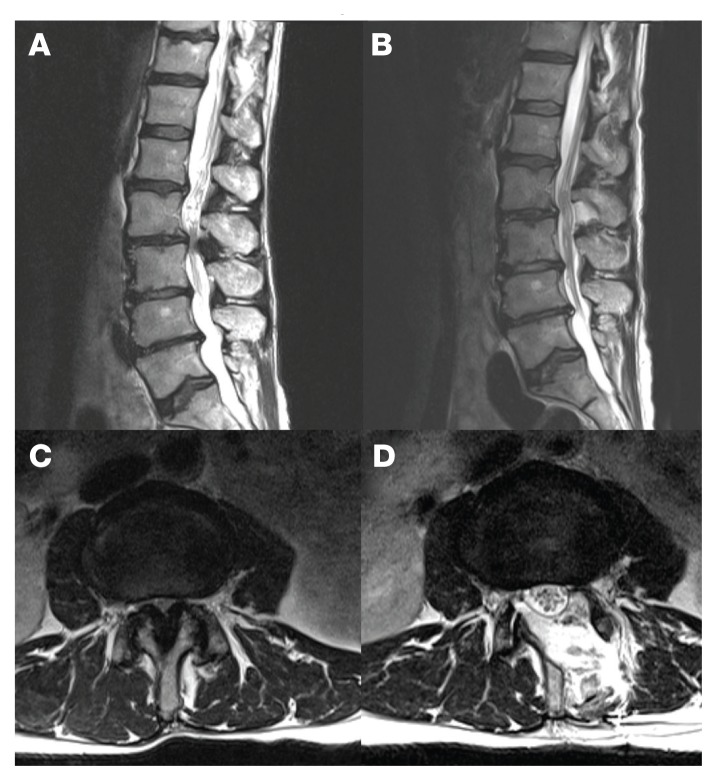

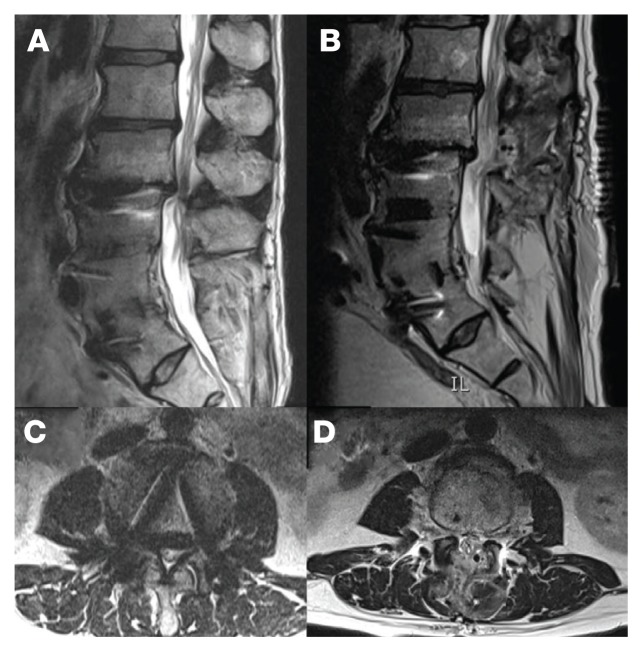

Fifty veterans with severe lumbar stenosis and neurogenic claudication underwent a 1- or 2-level laminectomy at SAVAHCS (Table). A traditional laminectomy was performed for all patients until conversion to the MIS procedure, then all subsequent patients underwent the microlaminectomy. There was 1 female patient in each group. The preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patients showed severe spinal canal stenosis defined radiographically by the absence of cerebrospinal fluid signal at the affected level on MRI (Figures 1A and 2A) and clinically by the presence of neurogenic claudication.

Table.

Cost-Related Outcomes

| Variable | Traditional | Microlaminectomy |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Patients, n | 13 | 37 |

|

| ||

| Operating room time, mean (SD), min | 131.25 (37.3) | 131.2 (46.8) |

|

| ||

| Surgical levels, mean | 1.7 | 1.4 |

|

| ||

| Blood loss, mean (SD), cc | 135 (78) | 46 (70)a |

|

| ||

| Outpatient, n (%) | 1 (7.7) | 28 (75.7) |

|

| ||

| Length of stay, d | ||

| Acute care, mean (SD) | 3.2 (2.1) | 0.8 (2.3)a |

| Rehab, mean (SD) | 5.2 (11.5) | 0.3 (1.4)b |

|

| ||

| Hospitalization cost, mean (SD), $ | 10,846 (7,603) | 1,961 (4,564)a |

P < .01.

P < .05.

Figure 1.

MRI of a Patient Undergoing a Microlaminectomy

Sagittal T2 weighted preoperative (A) and postoperative (B). The axial T2 weighted shows the extent of decompression preoperatively (C) compared with postoperatively (D).

Figure 2.

MRI of Patient Undergoing a Traditional 1-Level Laminectomy

Procedure

The open laminectomies were performed in a traditional midline approach with removal of the spinous process along with the lamina bilaterally to provide spinal canal decompression (Figure 2). The MISS laminectomies were performed through a small unilateral paramedian incision created 1.5 cm from the midline.1 A tubular retractor system was used, and the laminectomy was performed under microscope magnification. A laminotomy initially was completed ipsilateral to the side of the incision until the ligamentum flavum and the lateral recess of the spinal canal were identified. The tube was then aimed medially so that the base of the spinous process was identified and resected. The ligamentum flavum was dissected from the undersurface of the contralateral lamina. The contralateral lamina then was resected using a high-speed drill. Finally, the ligamentum flavum was resected, and the dura was exposed. The cranial-caudal extent of the resection was confirmed using fluoroscopy. The technique allowed for significant canal expansion (Figures 1A, B, C, and D).

The patients were given the choice of going home or being admitted. Overall admission costs were determined by the VA hospital following described models.18 The LOS in rehabilitation were determined from the records of the SAVAHCS rehabilitation center.

RESULTS

There was not a significant difference in age between the 2 groups; mean age was 69.7 ± 9.8 years for the traditional laminectomy group and 64.4 ± 8.3 years for the MIS group. Operating room time was just over 2 hours on average in both groups. Blood loss was estimated and reported by the surgeon and the anesthesiologist, based on values from the surgical suction system. Patients in the MIS group lost on average 46 cc ± 70 cc compared with 135 cc ± 78 cc in the traditional group. The average number of operated levels was higher in the traditional group (1.7 ± 0.5) compared with the MIS group (1.4 ± 0.5), but this difference did not reach significance (P > .05).

Length of Stay and Cost

The LOS was lower for the MIS group, and 76% chose to be discharged from the recovery room. After a traditional laminectomy, the average patient’s stay was 3 days in the hospital and 5 days in the rehabilitation center. The average MIS group patient stayed < 1 day in the hospital. There were no readmissions within 30 days and no severe morbidity (including no new neurologic deficits or death) in the MIS cohort.

Only 1 MIS patient needed transfer to the rehabilitation center. The estimated cost of care (hospital and rehabilitation) for the traditional group was $10,846 compared with $1,961 for the MIS group.

DISCUSSION

In the authors’ experience, the use of MISS microlaminectomy for the treatment of LSS seems to have led to shorter hospital stays and faster recoveries. Some of the possible reasons for faster patient mobilization included a reduction in postoperative pain and the absence of a wound drain. Larger dissections with a traditional laminectomy often lead to the placement of a wound drain, which requires an inpatient stay until the wound output reaches a certain threshold. The absence of a drain and the reduction in pain with the MISS approach allowed the providers to focus on early ambulation and discharge planning. The microlaminectomy technique allowed for a proper surgical decompression with less tissue dissection than is required for a traditional laminectomy. Previous studies have shown that the microlaminectomy technique provides significant symptomatic relief.5–7,17

In most cases, the microlaminectomy can be performed on an outpatient basis. The improvement in bed availability is particularly important as surgical procedures may be delayed when hospitals operate at full capacity. Redesigning a procedure typically requiring hospital admission into an outpatient procedure improves availability, allowing for better patient access to health care.19

Other authors have studied opportunities to transform inpatient neurosurgical care into outpatient procedures. For instance, Purzner and colleagues presented a large series of successful outpatient neurosurgical cases, including craniotomies, cervical fusions, and lumbar microdiscectomies.20 The MISS techniques offer a critical option to facilitate postoperative recovery and improve efficiency of care in regards to spine procedures.5,17

Cost-Effectiveness Within the VHA

The VA has been described as one of the best health care systems in the U.S.9 The arguments in favor of the VA system include its integrated computerized system and its resistance to health care cost inflation over the years.21 The $186.5 billion 2018 fiscal year VA budget is surpassed only by the total DoD budget, and it is expected to rise substantially in the near future.22

Redesigning a procedure typically requiring hospital admission into an outpatient procedure improves bed availability and reduces cost.19 The authors have demonstrated that a minimally invasive unilateral paramedian approach for the treatment of lumbar stenosis leads to shorter hospital stay, improved bed availability, and lower cost while allowing for a proper surgical decompression. These clinical results are in accord with previous MIS surgery studies.5,17 The improvement in bed availability is particularly important within the VA system. Elective surgeries occasionally are delayed or cancelled because hospitals operate at full capacity. However, the authors’ outpatient microlaminectomy patients avoid delays or cancellations.

Given that both laminectomy procedures use similar operating room resources (time and material), the lower LOS associated with the microlaminectomy translates in cost saving. At SAVAHCS, acute care hospitalization is estimated at $3,000 per day when accounting for various costs, including nursing, pharmacy, ancillary services, and maintenance. The MIS procedure costs about $9,000 less than the open surgery. Over a 2-year period with 37 MIS patients, SAVAHCS saved about $300,000.

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was assessed 1 day after the lumbar microdecompression outpatient surgery. Patients were asked to rate their overall surgical experience on a scale of 1 (worst) to 10 (best). All 24 patients who were contacted following outpatient lumbar microdecompression surgery rated the experience 10. These results indicate that patients do not expect or desire an admission following lumbar surgery, and they may recover comfortably at home. Studies are needed to compare outpatient and inpatient satisfaction ratings.

CONCLUSION

In this small sample, lumbar microlaminectomy significantly reduced LOS, successfully decompressed the spinal canal, and achieved symptomatic relief. Also, the procedure is associated with a lower blood loss than a traditional laminectomy and may reduce the rate of perioperative morbidity over time. In addition to faster recovery, the reduction in LOS can improve access to care by increasing the availability to inpatient admission.

Footnotes

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guiot BH, Khoo LT, Fessler RG. Spine. 4. Vol. 27. Phila PA: 1976. 2002. A minimally invasive technique for decompression of the lumbar spine; pp. 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman M, Summers LE, Richter B, Mimran RI, Jacob RP. Comparison of techniques for decompressive lumbar laminectomy: the minimally invasive versus the “classic” open approach. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51(2):100–105. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1022542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasai K, Umeda M, Maruyama T, Wakabayashi E, Iida H. Microsurgical bilateral decompression via a unilateral approach for lumbar spinal canal stenosis including degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9(6):554–559. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.8.08122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pao JL, Chen WC, Chen PQ. Clinical outcomes of microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(5):672–678. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yagi M, Okada E, Ninomiya K, Kihara M. Postoperative outcome after modified unilateral-approach microendoscopic midline decompression for degenerative spinal stenosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10(4):293–299. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.SPINE08288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong AP, Smith ZA, Lall RR, Bresnahan LE, Fessler RG. The microendoscopic decompression of lumbar stenosis: a review of the current literature and clinical results. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;2012:325095. doi: 10.1155/2012/325095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen DS, O’Toole JE, Eichholz KM, et al. Minimally invasive lumbar spinal decompression in the elderly: outcomes of 50 patients aged 75 years and older. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(3):503–509. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255332.87909.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoo LT, Fessler RG. Microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(suppl 5):S146–S154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mobbs RJ, Li J, Sivabalan P, Raley D, Rao PJ. Outcomes after decompressive laminectomy for lumbar spinal stenosis: comparison between minimally invasive unilateral laminectomy for bilateral decompression and open laminectomy: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21(2):179–186. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.SPINE13420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avila MJ, Walter CM, Baaj AA. Outcomes and complications of minimally invasive surgery of the lumbar spine in the elderly. Cureus. 2016;8(3):e519. doi: 10.7759/cureus.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oertel MF, Ryang YM, Korinth MC, Gilsbach JM, Rohde V. Long-term results of microsurgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis by unilateral laminotomy for bilateral decompression. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(6):1264–1269. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000245616.32226.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddadi K, Ganjeh Qazvini HR. Outcome after surgery of lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized comparison of bilateral laminotomy, trumpet laminectomy, and conventional laminectomy. Front Surg. 2016;3:199. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe K, Matsumoto M, Ikegami T, et al. Reduced postoperative wound pain after lumbar spinous process-splitting laminectomy for lumbar canal stenosis: a randomized controlled study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14(1):51–58. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.SPINE09933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skovrlj B, Belton P, Zarzour H, Qureshi SA. Peri-operative outcomes in minimally invasive lumbar spine surgery: a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2015;6(11):996–1005. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i11.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellander I. The deepening crisis in U.S. health care: a review of data. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(3):575–586. doi: 10.2190/HS.41.3.j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chokshi DA. Improving health care for veterans —a watershed moment for the VA. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):297–299. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1406868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang MY, Cummock MD, Yu Y, Trivedi RA. An analysis of the differences in the acute hospitalization charges following minimally invasive versus open posterior lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(6):694–699. doi: 10.3171/2009.12.SPINE09621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett PG. Determination of VA health care costs. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(suppl 3):S124–S141. doi: 10.1177/1077558703256483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Congressional Budget Office. The health care system for veterans: interim report. [Accessed October 13, 2017]. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/reports/12-21-va_healthcare.pdf. Published December 2007.

- 20.Purzner T, Purzner J, Massicotte EM, Bernstein M. Outpatient brain tumor surgery and spinal decompression: a prospective study of 1003 patients. Neurosurgery. 2011;69(1):119–126. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318215a270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waller D. How veterans’ hospitals became the best in health care. Time Magazine. [Accessed October 13, 2017]. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1376238,00.html. Published August 27, 2006.

- 22.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Budget. Annual budget submission—office of budget. [Accessed October 27, 2017]. https://www.va.gov/budget/products.asp. Updated July 12, 2017. Published October 13, 2017.