Abstract

We demonstrate the synthesis of protein-polymer hybrid hydrogel that can be used as a platform for immobilizing functional proteins. Orthogonal chemistry was employed for cross-linking the hybrid network and conjugating proteins to the gel backbone, allowing for the convenient, one-pot formation of a functionalized hydrogel. The resulting hydrogel had tunable mechanical properties, was stable in solution, and biocompatible.

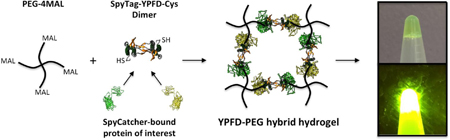

Graphical Abstract

We demonstrate the one-step bioorthogonal synthesis of protein-polymer hybrid hydrogel as a functional protein immobilization platform

Hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of cross-linked macromolecules that can swell under aqueous conditions. Their high water content and resemblance to biological tissue render hydrogels attractive for applications in biotechnology, such as tissue culture scaffolds, wound adhesives, biosensing materials and drug delivery matrices.1, 2, 3 Hydrogels created from synthetic polymers are particularly advantageous considering their low immunogenicity, ease of processing at large scale, and diverse range of crosslinking chemistries.4, 5, 6 Despite such advantages, applications of synthetic hydrogels as biomaterials are limited by their absence of bioactivity.7 To overcome this limitation, functional protein domains have been incorporated into polymeric hydrogel backbones to create protein-polymer hybrid networks, endowing the gels with complex abilities including stimuli-responsiveness, catalytic activity, or ability to regulate cell behaviors.8, 9, 10, 11 While a number of proteins have been utilized to fabricate functional synthetic hydrogels with hybrid structures, specific chemistries used to cross-link proteins with polymers are typically highly case-specific, reflecting a need for a generally applicable strategy to form hydrogels containing a variety of bioactive proteins.12, 13, 14

In this work, we created a novel protein-polymer hybrid hydrogel as a customizable platform for the stable incorporation of functional proteins. Within the hydrogel network, the protein component functions as a scaffold that captures functional proteins tagged with a specific recognition domain. As this attachment is orthogonal to the crosslink formation of the hydrogel backbone, the functionalized hydrogels can be conveniently and rapidly assembled via one-pot synthesis. Although the conjugation of functional proteins within hydrogels consisting purely of proteins has been reported previously,15–16 we describe here a generalizable platform for incorporating functional proteins into protein-polymer hybrid hydrogels.

We chose gamma-prefoldin (γPFD), a chaperone protein discovered from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, as the protein component of the hybrid hydrogel backbone considering its exceptional stability and ease of modular domain engineering.17 γPFD in its native state oligomerizes into filamentous structures having a broad length distribution;18 in order to achieve a regular hydrogel network, we used a previously designed variant of γPFD that only assembles as a dimer.19 The γPFD dimer has a unique structure consisting of two coiled-coils protruding from a beta-sheet barrel that is responsible for the dimerization20 (Fig. 1A). Since the distal regions of the helical coils corresponding to the N- and C-termini of each monomer are physically separate from the central barrel structure, engineering the tips of the helices to enable fusion with foreign proteins does not affect the dimeric assembly.21

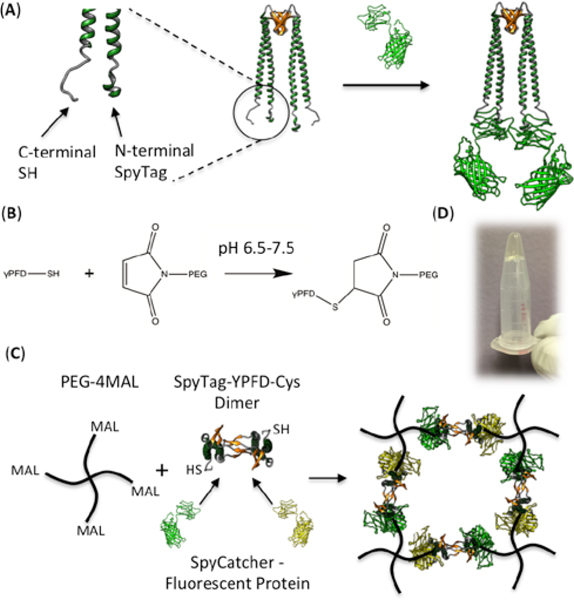

Fig. 1.

(A) Cartoon depiction of the SpyTag-γPFD-Cys dimer, before and after binding the fluorescent proteins through SpyTag-SpyCatcher interaction. N-terminal and C-terminal ends of one monomer are depicted in larger scale to the left. (B) Michael-type addition between thiol and maleimide groups. (C) Scheme of the bioorthogonal one-pot synthesis of the functionalized hybrid hydrogel network. Note that each dimer can contain either two of the same type of SpyCatcher-bound fluorescent protein, or one of each type (as shown). (D) Hybrid hydrogel formed in a microcentrifuge tube; the gel does not flow upon inverting the tube.

The recently developed SpyTag-SpyCatcher chemistry allows for highly efficient and precise conjugation between proteins tagged with the 13-residue SpyTag peptide and the counterpart proteins fused to the 12 kDa SpyCatcher domain.22 We genetically fused the SpyTag peptide to the N-terminal end of the γPFD monomer, and a cysteine residue to the C-terminal end to create SpyTag-γPFD-Cys, which was subsequently expressed and purified from an E. coli host. Thus, the dimers assembled from this modified subunit can scaffold two functional proteins of interest through SpyTag-SpyCatcher interaction, while forming chemical cross-links with polymer chains at both ends (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1). The polymer component that constitutes the hydrogel backbone was composed of maleimide-activated 4-arm polyethylene glycol (PEG-4MAL). The maleimide groups undergo Michael-type addition reactions to rapidly form cross-links with the C-terminal thiols of SpyTag-γPFD-Cys, (Fig. 1B) resulting in formation of a regular two-component hybrid network (Fig. 1C). The presence of the SpyTag domains in the hydrogel should enable efficient and specific incorporation of functional proteins fused to SpyCatcher. Thus, bioactive hydrogels can be formed in an orthogonal manner by mixing all three components (PEG-4MAL, SpyTag-γPFD-Cys and SpyCatcher-target protein) simultaneously in a single step.

Gelation was observed upon mixing the solutions of PEG-4MAL and SpyTag-γPFD-Cys prepared in a physiological phosphate buffer at a 1:4 molar ratio (Fig. 1D). Owing to the fast kinetics of the thiol-maleimide reaction, the gel formed almost immediately after the two parts were combined, making manual pipetting impossible after a few seconds. The formed gel swelled up by 60% (mass increase) after being submerged in phosphate buffer for 48 hours (Fig. S3).

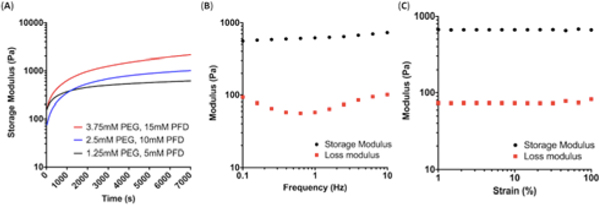

We performed oscillatory rheology experiments to characterize the mechanical properties of the hybrid hydrogel. The time sweep results depicted in Fig. 2A, which were measured at a fixed strain and frequency of 1% and 1 Hz, respectively, show that the storage modulus increased rapidly and reached a plateau after 2 hours of curing. As the total polymer and protein concentration was raised from 10 wt% (1.25 mM polymer and 5 mM protein) to 30 wt% (3.75 mM polymer and 15 mM protein), the plateau storage modulus increased from ~600 Pa to ~2000 Pa, demonstrating the tunability of the hydrogel’s mechanical strength. The storage modulus remained largely constant over a broad range of frequencies from 0.1 to 10 Hz during the frequency sweep tests, (Fig. 2B, Fig. S2A) and the gel moduli remained constant up to ~100% of the applied strain (Fig. 2C, Fig. S2B). Moreover, the storage modulus was higher than the loss modulus by roughly an order of magnitude over the entire range of measured frequencies and strains, indicating that the hybrid hydrogel displayed highly elastic behavior.23 For subsequent experiments, PEG-4MAL was used at the final concentration of 1.25 mM, along with 5 mM of γPFD (total solid content of 10 wt%).

Fig. 2.

(A) Change in storage modulus as a function of time after mixing the protein and polymer components. Measurements were performed at fixed frequency of 1 Hz and strain of 1%. (B) Frequency sweep of the hydrogel formed at 1.25 mM PEG and 5 mM γPFD, measured at fixed strain of 1%. (C) Amplitude sweep of the hydrogel formed at 1.25 mM PEG and 5 mM γPFD, measured at fixed frequency of 1 Hz.

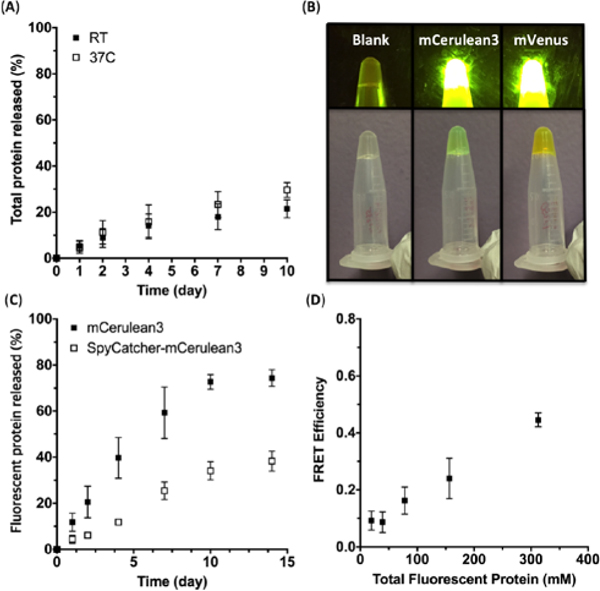

The stability of the hydrogels was investigated under aqueous conditions. Gels were cured for 6 hours and submerged in a phosphate buffer to test for the degree of erosion based on the amount of protein released to the solution. At room temperature, ~25% of total protein was released after 2 weeks (Fig. 3A). The hydrogel also exhibited stability at the elevated temperature of 37°C, which is required for applications such as cell culture or drug delivery (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3 .

(A) Total protein erosion profile of the hybrid hydrogels at room temperature and 37°C. (B) Hydrogels containing no fluorescent protein (left), mCeruluean3 (middle), and mVenus (right). The top images were taken under blue light, and the bottom images were taken under normal conditions. (C) Leaching profile of fluorescent proteins from the hybrid hydrogels formed with unmodified and SpyCatcher-fused mCerulean3. (D) FRET efficiencies of the hydrogels containing equal amounts of mCerulean3 and mVenus. The x-axis refers to the total fluorescent protein concentration, which was limited to a range showing a linear concentration-fluorescence behavior. All of the above experiments were performed at least twice, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. In some cases the error bars were smaller than the size of the symbols.

Having confirmed the mechanical tunability and stability of the “blank state” gel, we then synthesized bioactive hydrogels by incorporating SpyCatcher-bound functional proteins into the hybrid hydrogel network. As model proteins, fluorescent proteins mCerulean3 and mVenus were chosen for their stability, ease of quantification through fluorescence, and ability to interact with each other through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). The SpyCatcher domain was genetically fused to the N-terminal end of each fluorescent protein to create SpyCatcher-mCerulean3 and SpyCatcher-mVenus, which were subsequently expressed and purified from an E. coli host.

Theoretically, the maximum amount of SpyCatcher-bound protein that can be conjugated to the hydrogel is 5 mM, which is the molar equivalent of the available SpyTag domains. However, the fluorescent protein solution at such high concentration was too viscous to be pipetted even before being mixed with the other components to form the gel. Thus, we chose the final concentration of the fluorescent proteins within the gel to be 1.25 mM, which corresponds to 25% of the total available conjugation sites. Upon mixing the three components PEG-4MAL, SpyTag-γPFD-Cys and either SpyCatcher-mCerulean3 and SpyCatcher-mVenus, hydrogels were formed with colors indicative of fluorescent protein incorporation, with fluorescence emission upon exposure to blue light (Fig. 3B).

Isopeptide bond formation from the SpyTag-SpyCatcher interaction was confirmed by the upward shift of the protein bands from SDS-PAGE (Fig. S4). The rheology, swelling behaviour, and total protein erosion profile of the gel containing SpyCatcher-mCerulean3 were comparable to those of the gel formed without any additional incorporation of proteins, indicating that the presence of SpyCatcher-mCerulean3 did not affect the viscoelastic properties of the hydrogel or its integrity in solution (Fig. S5, S6). However, gels containing mCerulean3 without SpyCatcher fusion lost more than 70% of the total protein, suggesting that most of the non-covalently entrapped proteins leaked out of the gel (Fig. S6). Examining the extent of leaching based on the fluorescence measurement of the buffer also yielded consistent results; >80% of the native mCerulean3 was lost to the buffer after two weeks, whereas only ~35% of the SpyCatcher-mCerulean3 leached out (Fig. 3C). These observations demonstrate that the γPFD-PEG hybrid hydrogel can provide a general scaffold to stably attach bioactive proteins.

To non-invasively investigate the distribution of functional proteins immobilized in the hydrogel, equal amounts of SpyCatcher-mCerulean3 and SpyCatcher-mVenus were incorporated together into the gels; their total concentration was varied within the range in which the fluorescence intensity increases linearly with the concentration. When mCerulean3 and mVenus are positioned in close proximity (< 10 nm), the excited mCerulean3 transfers energy to mVenus, which results in a decrease in mCerulean fluorescence emission at 475 nm and an increase of mVenus emission at 528nm. As the total concentration of the fluorescent proteins increased from 20 μM to 320 μM, the FRET efficiency increased from almost zero to ~45% (Fig. 3D, S7, S8). These results suggest that multiple types of bioactive proteins can be simultaneously incorporated into the hydrogel, and that they can interact with each other if spaced in close proximity at high concentration. Thus, the hybrid hydrogel platform may prove particularly advantageous when close spatial proximity of multiple bioactive epitopes or enzymes is desired.24, 25

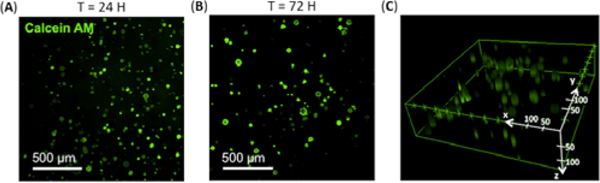

Finally, the hydrogel’s ability to support growth of mammalian cells in 3D culture was assessed using human embryonic stem cells (hPSCs). The hydrogel was prepared by adding SpyTag-γPFD-Cys into a solution of PEG-4MAL with hPSCs and triturated with a micropipette to achieve adequate cell encapsulation. After visually confirming gel formation and cell encapsulation with phase contrast microscopy, E8 maintenance media supplemented with Y-27632 was added to the 3D cell cultures, which were then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. Fluorescence-based live-cell staining as well as MTT assays revealed that ~90% of the seeded cells remained viable over a 72-hour culture period (Fig. 4A, 4B, S9). Further, the hPSCs were found to be distributed fairly evenly across x, y, and z dimensions of the gel (Fig. 4C). Overall, these data support that our γPFD-based hybrid hydrogel is non-cytotoxic, and can potentially be applied as a fully defined 3D culture system for delicate cell types, such as human embroyonic stem cells.

Fig. 4.

hPSC viability assay in hybrid hydrogel 3D culture system. Maximum intensity projection of confocal fluorescence microscopy stacks of human embryonic stem cells stained with calcein AM after (A) 24 hours and (B) 72 hours of encapsulation in hybrid hydrogel. (C) 3D depiction of viable hPSCs distributed across the hydrogel matrix at 24 hours.

In conclusion, we have developed a general strategy for the convenient, one-step immobilization of bioactive proteins into hydrogel. The gel network is formed by cross-linking PEG polymers with γPFD dimers via thiol-maleimide reaction, while the functional components are conjugated through SpyTag-SpyCatcher chemistry. Such bioorthogonal design allows for the one-step synthesis of the functionalized hydrogel by simply mixing three components under physiological conditions, providing an advantage over conventional methods to incorporate proteins into hydrogel networks. The resulting hydrogel is tunable in its mechanical properties, stable under aqueous conditions, and highly biocompatible. Furthermore, the strategy demonstrated here is applicable to any proteins or enzymes of interest by simple genetic fusion to the docking domain. Thus, we envision that our hybrid hydrogel can be used as a versatile platform for designing biomaterials for a wide variety of applications including multi-step biocatalysis and stem cell culture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550–17-1–0451). S.L. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE1106400, DGE1752814). The Perkin Elmer Opera Phenix microscope in the High-Throughput Screening Facility at UC Berkeley was provided by NIH Instrumentation Grant (S10OD021828). The authors thank Dr. Dawei Xu for helpful comments, and Professor Sanjay Kumar for use of the rheometer.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Materials and methods, supplementary figures. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Webber MJ, Appel EA, Meijer EW and Langer R, Nat. Mater, 2016, 15, 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teixeira LSM, Feijen J, van Blitterswijk CA, Dijkstra PJ and Karperien M, Biomaterials, 2012, 33, 1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghobril C and Grinstaff MW, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2015, 44, 1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Rodrigues J and Tomas H, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2012, 41, 2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naahidi S, Jafari M, Logan M, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Bae H, Dixon B and Chen P, Biotechnol. Adv, 2017, 35, 530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phelps EA, Enemchukwu NO, Fiore VF, Sy JC, Murthy N, Sulchek TA, Barker TH and Garcia AJ, Adv. Mater, 2012, 24, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cambria E, Renggli K, Ahrens CC, Cook CD, Kroll C, Krueger AT, Imperiali B and Griffith LG, Biomacromolecules, 2015, 16, 2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto T, Isogawa Y, Tanaka T and Kondo A, Biosens. Bioelectron, 2018, 99, 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito F, Usui K, Kawahara D, Suenaga A, Maki T, Kidoaki S, Suzuki H, Taiji M, Itoh M, Hayashizaki Y and Matsuda T, Biomaterials, 2010, 31, 58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sui Z, King WJ and Murphy WL, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2008, 18, 1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esser-Kahn AP, Lavarone AT and Francis MB, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2008, 130, 15820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez M, Guan D, Ugaz V and Chen Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopecek J and Yang J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheldon RA, Adv. Synth. Catal, 2007, 349, 1289. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao X, Lyu S and Li H, Biomacromolecules, 2017, 18, 3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan D, Ramirez M, Shao L, Jacobsen D, Barrera I, Lutkenhaus J and Chen Z, Biomacromolecules, 2013, 14, 2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehead TA, Boonyaratanakornkit BB, Hollrigl V and Clark DS, Protein Sci, 2007, 16, 626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glover DJ, Giger L, Kim JR and Clark DS, Biotechnol. J, 2013, 8, 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitehead TA, Meadows AL and Clark DS, Small, 2008, 4, 956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glover DJ and Clark DS, FEBS J, 2015, 282, 2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glover DJ, Giger L, Kim SS, Naik RR and Clark DS, Nat. Commun, 2016, 7, 11771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zakeri B, Fierer JO, Celik E, Chittock EC, Schwarz-Linek U, Moy VT and Howarth M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 2012, 109, E690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Partlow BP, Hanna CW, Rnjak-Kovacina J, Moreau JE, Applegate MB, Burke KA, Marelli B, Mitropoulos AN, Omenetto FG and Kaplan DL, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2014, 24, 4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YH, Campbell E, Yu J, Minteer SD and Banta S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2013, 52, 1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pashuck ET, Duchet BJR, Hansel CS, Maynard SA, Chow LW and Stevens MM, ACS Nano, 2016, 10, 11096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.