Abstract

In patients with diabetes, psychological well-being constructs (e.g., optimism, positive affect) have been associated with superior medical outcomes, including better glucose control and lower mortality rates. Well-being interventions may be well-suited to individuals with diabetes, as they are simple to deliver, broadly applicable across a range of psychological distress, and may help increase self-efficacy and motivation for diabetes self-care. This systematic review, completed using PRISMA guidelines, examined peer-reviewed studies indexed in PubMed, PsycINFO, and/or Scopus between database inception and October 2017 that investigated the effects of well-being interventions (e.g., positive psychology interventions, mindfulness-based interventions, resilience-based interventions) on psychological and physical health outcomes in individuals with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes. The search yielded 34 articles (N=1635 participants), with substantial variability in intervention type, measures used, and outcomes studied; the majority found the intervention to provide benefit. Overall, results indicate that a range of well-being interventions appear to have promise in improving health outcomes in this population, but the literature does not yet provide definitive data about which specific interventions are most effective. The variability in interventions and outcomes points to a need for further rigorous, controlled, and well-powered studies of specific interventions, with well-accepted, clinically relevant outcome measures.

Keywords: diabetes, well-being, positive psychology, mindfulness, ACT, resilience, positive affect

Diabetes affects 29 million US adults [1], and its prevalence is rising. Especially when poorly controlled, diabetes can lead to significant cardiovascular and microvascular complications along with increased mortality [1]. Managing diabetes requires persistent effort and adherence to multiple health behaviors, and many patients struggle to manage this chronic condition. Among individuals with diabetes, depression and anxiety are common [2]. Even those without a mood or anxiety disorder often have substantial psychological distress that impedes functioning and quality of life in both type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [3]. Psychological distress and depression appear to impact health behavior and medical outcomes strongly in patients with diabetes [4–7]. For example, distress is linked to lower treatment adherence [3], and depression is associated with impaired glucose control [8, 9], end-organ complications [8], and mortality [8, 10, 11].

In contrast, indicators of psychological well-being, including optimism, positive affect, self-efficacy, and gratitude, have been prospectively associated with superior health outcomes across numerous medical conditions, independent of sociodemographic and medical factors. Collectively termed “well-being constructs,” these indicators are not simply the flip-side of depression [12, 13], and their beneficial effects have been demonstrated independently from the adverse effects of depression and anxiety [14, 15]. Regarding diabetes, a large epidemiological study found that higher levels of emotional vitality and life satisfaction were associated prospectively with a lower risk of T2D [16]. Among those with existing diabetes, optimism, resilience, self-efficacy and positive affect have been associated with better glycemic control, greater health behavior adherence, and lower mortality [17–24].

These observational studies linking psychological well-being with health outcomes raise questions about whether such well-being constitutes a static trait or if it is modifiable. In other populations, there is a substantial literature on the efficacy of specific interventions in promoting well-being and impacting health outcomes. For example, positive psychology (PP) interventions, a type of well-being interventions, utilize exercises (e.g., gratitude letters, acts of kindness, using personal strengths) designed to promote optimism, positive affect, and resilience. A recent meta-analysis in over 5000 healthy participants revealed these interventions increase well-being and decrease depression [25]. PP programs have also been found to improve psychological and health outcomes in individuals with chronic medical conditions such as heart disease, hypertension, and HIV [26–31]. Mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based stress reduction) are even more extensively studied, and a meta-analysis examining 209 studies of these interventions showed consistent improvements in anxiety, depression, and stress [32].

Well-being interventions may be well-suited to diabetes patients for several reasons. First, they target constructs (e.g., optimism, resilience) that have been prospectively and independently linked to superior health outcomes in diabetes [4]. Second, as opposed to interventions specifically for psychiatric conditions, well-being interventions are broadly applicable across a wide range of individuals, including those without psychiatric illness [33], an important factor given that the majority of diabetes patients do not have a psychiatric condition but still experience substantial distress [2]. Third, managing diabetes involves difficult lifestyle changes regarding diet, physical activity, medications, and blood sugar monitoring. Well-being interventions can promote motivation and self-efficacy, which, in turn, may improve self-care. Finally, many well-being interventions are simple for patients and can be delivered or assigned by clinicians without the need for intensive training.

Despite these many potential benefits, we are aware of no prior synthesis of the literature on well-being interventions in diabetes. Accordingly, we conducted a systematic review of wellbeing intervention studies in individuals with diabetes to best understand the current state of the literature and ongoing clinical and research needs.

Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [34] guidelines and criteria were followed when conducting and reporting this review.

Search Strategy

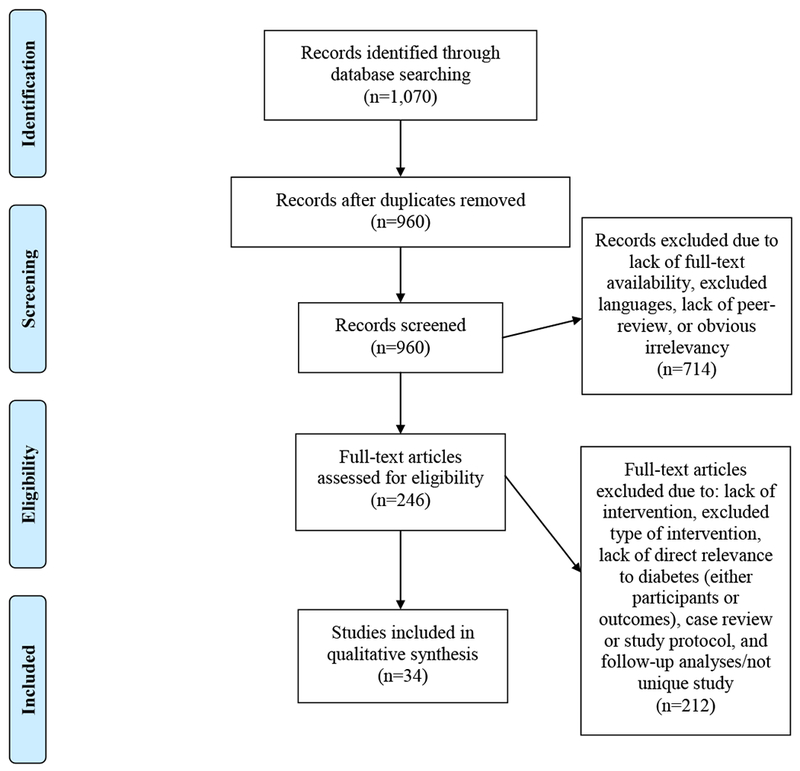

Systematic searches were completed in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus electronic databases in October 2017 using keyword-based queries (see Supplementary Table 1) that included peer-reviewed publications from database inception through October 2017. After removal of duplicates, titles of remaining articles were reviewed by three authors (CM, EF, LD) and clearly irrelevant articles were eliminated. The authors then reviewed remaining abstracts to identify further articles for elimination (see below for detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria). Finally, the authors reviewed the full text of remaining articles. See Figure 1 for a summary diagram of the article selection process.

Figure 1.

Article selection process. Adapted from Moher, Liberati, Tatzlaff, & Altman (2009).

Selection Procedure

This review included peer-reviewed manuscripts published in English, Spanish, and/or Persian (languages spoken by lab members). PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study design) guidelines [35] were used to establish specific inclusion/exclusion criteria. To be included, articles must have: a) had participants diagnosed with diabetes, b) assessed an intervention designed to promote well-being (rather than aiming to reduce a negative construct), and c) used a prospective study design. Case studies, case reports, and abstracts were excluded. Well-being interventions included, but were not limited to, the following:

PP interventions focus on increasing psychological well-being through deliberate completion of specific activities (e.g., counting blessings, identifying/using personal strengths) [13, 36]

Mindfulness-based interventions focus on cultivating mindfulness (a mental state achieved by focusing one’s awareness on the present moment) and range from mindfulness meditation practice to multifaceted interventions that combine mindfulness meditation with cognitive therapy, goal-setting and/or educational programs, or stress-reduction programs. We specifically included mindfulness-based interventions because they fit the inclusion criteria of having a prospective study design and using specific skills and exercises to promote well-being in individuals with diabetes [37].

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) combines mindfulness and acceptance strategies with behavioral change and commitment techniques to promote awareness of emotional experience, emotion regulation, and decreased avoidance (e.g., see [38] for description of ACT intervention).

Resilience-based programs focus on improving well-being through teaching new adaptive coping methods. Rather than targeting ways to repair existing problems, they build resources and positive assets [39].

We allowed variation in intervention duration, follow-up periods, and comparators (including studies with no comparison group). We recorded the observed intervention effect on both psychological and physical health outcomes. Two authors independently reviewed each article for quality and risk of bias using the Effective Public Health Practice Project’s Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [40], resolving discrepancies in ratings via review and discussion. This quality rating tool assesses the following areas: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, attrition, intervention integrity, and analyses, and yields an overall global rating (strong, moderate, or weak).

Results

Study Characteristics

We identified 34 articles from 30 studies meeting all inclusion criteria (some articles reported different outcomes within the same study and were included as unique selections). These consisted of four PP articles [41–44], 18 mindfulness-based articles [45–62], six ACT articles [38, 63–67], four resilience-based articles [68–71], and single studies targeting emotional intelligence [72] and positive self-concept [73] (see Tables 1 and 2 for details about studies with control groups and studies without control groups, respectively).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Well-Being Intervention Studies with Control/Comparison Groups

| Authors | Sample Size | Sample Characteristics | Intervention Description | Psychological Outcomes (significant in bold) | Effect Size | Physical Health Outcomes (significant in bold) | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP Interventions | |||||||

| Cohn et al., (2014) | 49 | Adults with T2D 51% female Median age 54 | Online, 60-day, self-paced intervention to enhance positive emotion or adaptive coping Control group: Reported emotions daily on website |

Depression Perceived stress Positive affect Negative affect Confidence in DM self-care Diabetes-related distress |

β=−.21 β=−.13 |β|<.15 |β|<.15 |β|<.09 |β|<.09 |

Medication adherence Glucose testing adherence Physical activity |

|β|<.19 |β|<.19 |β|<.19 |

| Jaser et al., (2014) | 39 | Adolescent (age 13-17) outpatients with T1D Intervention group: 60% female Mean age 15.3 (SD=1.4) Control group: 42.1% female Mean age 15.0 (1.6) |

Positive affect intervention delivered in one in-person visit and bi-weekly phone calls over 8 weeks Control group: Education (biweekly mailed materials) |

Positive affect | NR | Self-reported average daily glucose | NR |

| Nowlan et al. (2016) | 81 | Australian older adults (age 60+) with T2D 40% female Mean age 71.7 (7.4) | Positive Reappraisal program delivered in one 50-minute in-person session Comparison group: Cognitive Restructuring Control group: supportive counseling |

Positive reappraisal Positive emotion Negative emotion Anxiety Depression |

ηp2=.16 ηp2=.09 NR NR NR |

||

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions | |||||||

| Haenen et al. (2016) | 139 | Outpatients with low levels of emotional wellbeing with T1D or T2D Intervention Group: 53% female Mean age 56 (13) Control Group: 46% female Mean age 57 (13) |

Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy delivered in weekly groups for 8 weeks with one booster session 3 months later Control group: wait list |

Mood Anger Fatigue Vigor Mindfulness |

ηp2=.07 ηp2=.10 ηp2=.09 ηp2=.04 −.07 |

HRQoL | NR |

| Jung et al. (2015) | 56 | Male and female outpatients with T2D from South Korean hospital (no demographic info) | Korean Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program delivered in twice weekly groups for 8 weeks Comparison groups: walking exercise and patient education groups delivered weekly |

Diabetes-related Stress Psychologica l Response to Stress |

NR NR |

Cortisol Level Vascular Inflammation Blood Glucose Level |

(All NR) |

| Miller et al. (2014) | 52 | Individuals with T2D Intervention Group: 63% female Mean age 53.9 (8.2) Comparison Group: 64% female Mean age 54.0 (7.0) |

Mindfulness Eating for Diabetes (MB-EAT-D) program delivered in groups for 3 months with follow-ups 1 and 3 months post-intervention Control group: educational/goal-setting program |

Depression Mindfulness Self-Efficacy Related to Diabetes Nutrition Self-Efficacy in Controlling Overeating Cognitive Control of eating Disinhibition of Control Anxiety Quality of Life Susceptibility to Nonphysical Hunger |

(All NR) |

Weight Outcome Expectations for Making Health Food Choices Food Intake Nutrition Knowledge Diabetes Meal Planning Glycemic Control |

(All NR) |

| Rungreangkul kij et al. (2011) | 64 | Individuals with T2D 93.8% female overall Intervention Group: Mean age 50.0 (10.6) Control Group: Mean age 47.0 (9.5) |

Buddhist Mindfulness delivered in weekly groups for six weeks; one follow-up at six months Control group: TAU |

Depression | d=1.74 | ||

| Schroevers et al. (2015) | 24 | Individuals with T1D or T2D 42% female Intervention Group: Mean age 54.9 (10.3) Control Group: Mean age 55.9 (8.2) |

Individual Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (I-MBCT) delivered in individual sessions for 8 weeks with a follow-up at 3 months Control group: waitlist |

Depression Diabetes-related Distress Attention Regulation Mindfulness: Act with Awareness Mindfulness: Accept Without Judgment |

d=1.23 d=1.08 d=.93 d=.63 NR |

||

| Friis et al. (2016) | 63 | Outpatients with T1D or T2D 68% female Mean age 44.4 (15.6) |

Mindful Self-Compassion Group delivered in group sessions for 8 weeks; three-month follow-up Control group: Waiting List/TAU |

Self-Compassion Depression Diabetes-specific Distress | ηp2=.21 ηp2=.19 ηp2=.29 |

HBA1C (at 3 mos) | ηp2=.15 |

| Gainey et al. (2016) | 23 | Outpatients with T2D 82.6% female Intervention Group: Mean age 58 (3) Control Group: Mean age 63 (2) |

Buddhism-Based Walking: Meditation Exercise delivered in-person for 12 (with thrice-weekly walks) Comparison group: Traditional Walking Group |

Blood Pressure Arterial Stiffness HbA1C Cortisol Flow-Mediated Dilation Ankle Brachial Index Fasting Blood Glucose Body Mass Index Maximal Oxygen Consumption Muscle Strength Insulin Lipid Profile |

(All NR) | ||

| Hartmann et al. (2012) | 110 | Outpatients with T2D Intervention Group:32.5% female Mean age 58.7 (7.4) Control Group: 19.3% female Mean age 59.3 (7.8) |

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction delivered in group sessions for 8 weeks with one booster session 6 months later; follow-ups annually for 5 years Control group: TAU |

Depression Stress Mental Health Status (outcomes significant only at 1 year follow-up) |

d=.71-.79 d=.48-.64 d=.54-.65 |

Blood Pressure Diastolic Systolic Albuminuria Physical Health Status HBA1C (outcomes significant only at 1 year follow-up) |

d=.68-.78 d=.39-.42 d=.40-.44 d=.19-.23 d=.37-.47 |

| Teixeira (2010) | 20 | Individuals with T2D and painful diabetic neuropathy 75% female Mean age 74.6 (10.8) | Mindfulness meditation instruction/practice delivered in one in-person class and four weeks of at-home practice with an audio CD Control group: Nutrition education |

Sleep Quality Neuropathic Pain Neuropathy-specific Quality of Life |

r=.53 ηp2=.001-.16 ηp2=.05 |

||

| Tovote et al. (2014) | 94 | Outpatients with T1D or T2D and depressive symptoms 49% female Mean age 53.1 (11.8) |

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MCBT) delivered in individual sessions over 8 weeks with daily homework Comparison group: CBT Control group: Waitlist |

Depression Diabetes-related Distress Anxiety Well-being *Significant differences were found for MBCT group compared to the control; no differences found between MBCT and CBT groups |

d=.80-1.17 d=.52 d=.98 d=.92 |

HBA1C | NR |

| Tovote et al. (2017) | 91 | Outpatients with either T1D or T2D and depressive symptoms 50% female Mean age 53.2 (11.9) |

MCBT delivered in individual sessions over 8 weeks with daily homework Comparison group:CBT |

Depression (moderated by education level) | NR | ||

| van Son et al. (2013) | 139 | Outpatients (T1D or T2D) with low levels of emotional wellbeing MBCT Group: 53% female Mean age 56 (13) Control Group: 46% female Mean age 57 (13) |

MCBT delivered in in-person group sessions for 8 weeks with one booster session 3 months post-intervention Control group: Waitlist |

Perceived Stress Anxiety Depression Mental HRQoL Fatigue Diabetes-Specific Distress |

d=.70 d=.44-.82 d=.59-.71 d=.55 d=.58 d=.21 |

Physical HRQoL HBA1C |

d=.40 d=.14 |

| Wagner et al. (2015) | 107 | Hispanic/Latino outpatients with T2D Mindfulness group: 74% female Mean age 60.0 (11.2) Control group: 72% female Mean age 60.8 (12.1) |

Mindfulness meditation and stress management in-person weekly group intervention for 8 weeks Control group: Diabetes education |

In-Session Positive Affect In-Session Negative Affect Treatment Satisfaction Therapeutic Cohesion |

NR NR NR NR |

Diabetes Knowledge | NR |

| Wagner et al. (2016) | 107 | Same as above | Same as above |

Depression Anxiety Diabetes distress |

R2=.086 R2=.077 R2=.000 |

Self-Reported Health Status HBA1C Cortisol Diabetes Self-Care | R2=.048 R2=.015 R2=.012 R2=.000 |

| Sasikumar & Latheef (2017) | 40 | Individuals from India with T2D for ≥1 year MBSR group: 60.0% female Control group: 61.1% female 38.9% in the 45-49 age group (mean not reported) |

MBSR delivered in group format plus daily practice for 8 weeks Control group: Waitlist |

Stress Depression Mindfulness | (All NR) | ||

| ACT Interventions | |||||||

| Gregg et al. (2007) | 73 | Outpatients with T2D ACT Group: 48.8% Female Mean age 51.9 Control Group: 57.9% Female Mean age 49.8 |

ACT and education workshop delivered in a 7-hour group session, with a 3-month follow-up Control group: Education only |

ACT processes Satisfaction with Treatment |

d=.78 NR |

Diabetes Self Management-Adherence Diabetic Control HBA1C Understanding of Diabetes |

d=.68 d=.61 d=.35 d=.30 |

| Shayeghian et al. (2016) | 100 | Outpatients with T2D ACT Group: 66% Female Mean age 55.2 (8.3) Control Group: 54% Female Mean age 55.7 (9.0) |

ACT and education workshop delivered in 10 group sessions with a 3-month follow-up Control group: Education only |

ACT processes | ηp2=.44 | HBA1C Diabetes Self Management-Adherence | ηp2=.25 ηp2=.22 |

| Moazzezi et al. (2015) | 32 | Adolescents (ages 7-15) with T1D or T2D ACT Group: 25% Female Mean age 11.4 (2.6) Control Group: 43.75% Female Mean age 9.7 (2.4) |

ACT workshop delivered in 10 group sessions Control group: TAU |

Total Perceived Stress Negative Perceived Stress Positive Perceived Stress | (All NR) | Special Health Self-Efficacy | NR |

| Moghanloo et al. (2015) | 34 | Adolescents (ages 7-15) with T1D or T2D ACT Group: 52.94% Female Mean age 10.4 (2.9) Control Group: 47.06% Female Mean age 10.6 (3.2) |

ACT workshop delivered in 10 group sessions Control group: TAU |

Depressive Symptoms Feeling of Guilt Psychologic al Well-Being | (All NR) | ||

| Whitehead et al. (2017) | 106 | Individuals with uncontrolled T2D ACT Group: 41% Female Mean age 53.8 (8.7) ACT + Education: 56% Female Mean age 56.1 (6.9) Control Group: 42% Female Mean age 56.4 (7.0) |

ACT and Education workshop delivered in a 6.5 hour group session with 3-month and 6-month follow-up Comparison group: Education Only Control group: TAU |

Acceptance of Diabetes Understanding Diabetes Satisfaction with Diabetes Management Anxiety Depression |

(All NR) | HBA1C (significant only between education and control groups) Understanding Diabetes Diabetes-related Self-Management |

(All NR) |

| Resilience Interventions | |||||||

| Steinhardt et al. (2015) | 65 | African American adults with T2D 72% female Mean age 62 (10.3) |

Resilience-based diabetes self-management education program delivered in 8 weekly in-person groups plus 2 bi-weekly support group sessions Control group: Groups without resilience component |

Positive meaning Positive adaptation to stress Coping Positive affect Negative affect Quality of life Perceived stress Depression |

d=.61 d=.24 d=.21 d=.42 d=.29 d=−.30 d=−.45 d=−.11 |

DM knowledge Fasting blood glucose HDL cholesterol LDL cholesterol Physical activity Blood glucose self-monitoring BMI HBA1C Triglycerides Systolic blood pressure Diastolic blood pressure |

d=.75 d=−.59 d=.84 d=−.47 d=.40 d=.50 d=−.15 d=−.27 d=.45 d=−.35 d=−.18 |

| Bradshaw et al. (2007)* | 67 | 65% female Intervention Group: Mean age 60.8 (10.9) Control Group: Mean age 57.5 (11.0) Adult outpatients with T2D referred for DM education |

Resilience intervention delivered in in-person groups twice a week for 5 weeks Control group: TAU |

Resiliency(at 6 mos.) Self-efficacy Locus of control Social support Purpose in life | ηp2=.156 NR NR NR NR |

Barriers to physical activity (at 3 mos.) HBA1C Waist circumference Compliance with DM self-management Blood glucose management Physical activity Healthy diet |

ηp2=.141 NR NR NR NR NR NR |

| Rosenberg et al. (2015) | 30 | Adolescent or young adults (age 15-25) with T1D diagnosed ≥6 months ago or cancer diagnosed ≥2 weeks ago Diabetes Group: 67% female Mean age 15.1 (11.3) Cancer Comparison Group: 58% female Mean age 16.2 (2.8) |

Promoting Resilience in Stress Management program delivered in 2 individual sessions Comparison group: Same intervention |

Resilience | d=.15 | ||

| Other Well-Being Interventions | |||||||

| Yalcin et al. (2008) | 36 | Turkish adults (age 40-60) with T2D 50% female Intervention Group: Mean age=54.3 (7.3) Control Group: Mean age=51.2 (5.8) |

Emotional Intelligence intervention delivered in 12 weekly group sessions Control group: Wait List |

Emotional Intelligence Well-being Quality of life | z=5.129 z=4.514 z=4.568 |

Physical functional status | z=2.595 |

| Voseckova et al. (2017) | 46 | Older adults (age 65-70) with T2D in Czech Republic 61% female Mean age 69 (14) |

Humanistic psychotherapy intervention focused on strengthening self-concept and perceived self-efficacy delivered in 8 monthly in-person groups Control group: TAU |

Subjective feelings and states Hardiness | NR NR |

Fasting blood glucose HBA1C | NR NR |

Note. HRQoL=Health-Related Quality of Life. NR=Not reported in article. d=Cohen’s d. ηp2=partial eta squared. R2=R squared. TAU=treatment as usual. (β=beta. z=z score comparing post-test scores in intervention versus control group.

Description of results is presented at item level and is unclear regarding effect sizes for larger constructs in most cases

Table 2.

Characteristics of Well-Being Intervention Studies without Control/Comparison Groups

| Authors | Sample Size | Sample Characteristics | Intervention Description | Psychological Outcomes (significant in bold) | Effect Size | Physical Health Outcomes (significant in bold) | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP Interventions | |||||||

| DuBois et al. (2016)* | 15 | Adults with T2D and suboptimal adherence 58.3% female Mean age 61.4 (7.0) |

PP phone-delivered intervention over 12 weeks Control group: None |

Optimism Gratitude Depression Anxiety Diabetes-related distress HRQoL |

d=.56 d=.27 d=.56 d=.68 d=.40 d=.28 |

Diabetes self-care behaviors Health behavior adherence |

d=1.00 d=.72 |

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions | |||||||

| Drager et al. (2015) | 11 | Aboriginals with T2D 90.9% female Mean age 60.1 (8.7) | MBSR delivered in group sessions for 8 weeks Control group: None |

Emotional Well-Being Stress Depression Anxiety Satisfaction with Life Mindfulness |

d=.71-.75 d=.07-.17 d=.25-.47 d=.18-.45 d=.01-.07 d=.18-.19 |

HBA1C Mean Arterial Pressure Systolic BP General Health Diastolic BP Weight Diet Exercise |

d=.63-.83 d=.61-.85 d=.69-1.15 d=.35-.39 d=.34-.39 d=.02-.03 d=.04-.38 d=.09 |

| Rosenzweig et al. (2007) | 14 | Individuals with T2D 64.3% female Mean age 59.2 (2.6) | MBSR delivered in group sessions for 8 weeks; one month follow-up Control group: None |

Depression Anxiety Somatization General Psychological Distress |

d=.86 d=.43 NR d=.60 |

BA1C (follow-up only) Mean Arterial Pressure (follow-up only) Body Weight |

d=.46-.88 d=.27-.48 d=.04-.09 |

| Young et al. (2009) | 25 | Individuals with T1D or T2D 60% female Mean age 56 (10) |

MBSR delivered in in-person groups for 8 weeks plus one all-day retreat Control group: None |

Mood (significant pre-post change; no control group) | NR | ||

| ACT Interventions | |||||||

| Nes et al. (2012) | 11 | Individuals with T2D 33.4% female Mean age 59.6 | Online/Text Message ACT program for 3 months Control group: None |

Diabetes-related distress *Feasibility study, only descriptive results |

NR | HBA1C BMI Diabetes-Related Quality of Life *Feasibility study, only descriptive results |

(All NR) |

| Resilience Interventions | |||||||

| Steinhardt et al. (2009) | 16 | African American adults with T2D 50% female Mean age 54.8 | Resilience intervention plus nutrition education delivered in 4 weekly classes plus 8 bi-weekly informal support groups Control group: None |

Diabetes empowerment Resilience Coping strategies Perceived stress Depression |

d=1.23 d=.10 d=−.18 d=−.26 d=.03 |

BMI HBA1C Total cholesterol LDL cholesterol Systolic blood pressure Diastolic blood pressure DM self-management HDL cholesterol Fasting blood glucose |

d=−.99 d=−1.04 d=−.70 d=−1.80 d=−.80 d=−.71 d=.74 d=.09 d=−.18 |

Note. NR=Not reported in article. d=Cohen’s d.

Significance not tested due to lack of control group

Control conditions varied significantly across studies. Nine studies provided diabetes education to control participants, seven used an active control condition (with one study using both a waitlist control and an active control), 14 used a waitlist or treatment-as-usual control (one study had both a diabetes education comparison group and a treatment-as-usual group), and six were uncontrolled. When discussing results below, uncontrolled studies are noted; otherwise, all results refer to change in the intervention group relative to the control. Overall, 12% (n=4) of studies were rated as high quality, 62% (n=21) as moderate quality, and 27% (n=9) as poor quality.

Study Samples

In total, the identified studies included 1,635 participants, 103 of whom were adolescents. When demographics were reported, in studies of adults, 54.7% of participants were female, 46.9% were Caucasian/White, and the mean age was 51.6 years. Of adolescent participants, 46.6% were female, 77.8% were Caucasian/White, and the mean age was 13.8 years. Twenty-three of the 34 articles included only patients with T2D; two included only individuals with T1D; the remaining nine included individuals with T1D or T2D. No studies of gestational diabetes were identified. Four studies included children/adolescents, and the remainder included only adults. Most articles (n=25) described group-based interventions, and all but four interventions were delivered in person, with others using texting, internet, or phone-based delivery. See Supplementary Table 2 for outcome measurement information.

PP Interventions (four studies)

Psychological Outcomes.

Few positive psychological outcomes were examined in these studies. Three out of four PP studies measured positive affect, with only one finding significant improvement (with small effect size)[44]. The constructs of optimism and gratitude were also measured in one study (which did not test for significance)[43]. Otherwise, depression was measured in three of four PP studies. Among the two controlled studies, depression significantly changed in only one that examined the efficacy of an online, self-paced PP intervention [41]. Anxiety was measured in two studies; however, only one used a control group, and it found no statistically significant changes in anxiety [43]. Numerous other psychological outcomes were measured in the PP studies (see Tables 1 and 2) including perceived stress, confidence, and emotion, none of which showed statistically significant changes.

Physical Health Outcomes.

All PP studies relied on self-report for physical health outcomes. In studies that tested for statistical significance, there were no significant findings for any health-related outcome, including glucose monitoring, medication adherence, or physical activity.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions (18 studies)

Psychological Outcomes.

Mindfulness-based intervention studies examined a wide range of both well-being related outcomes and other types of psychological outcomes including emotional well-being, self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, diabetes-related distress, depression, anxiety, and anger. Of the well-being outcomes, significant changes were seen in self-efficacy [48], self-compassion [51], well-being [45, 56], mental health-related quality of life [58], and positive affect [59]. Of the remaining outcomes, stress, diabetes-related distress, depression, and anxiety were most often studied and were most consistently reduced post-intervention. Of the five studies that examined stress as an outcome, four found a significant reduction following the intervention [45, 53, 58, 62], although only three [53, 58, 62] of these were controlled studies. Similarly, of the 12 studies measuring changes in depression, 11 found significant symptom reductions [48–51, 53, 54, 56–58, 60, 62], 10 of which were controlled studies. With respect to anxiety and diabetes-related distress, three out of six studies that measured these outcomes found a significant reduction following the intervention [50, 51, 56, 58, 60] compared to the control group.

Two follow-up studies were identified. One indicated that at six-month follow-up, significant reductions in perceived stress, anxiety, and depression found after an eight-week mindfulness-based cognitive therapy intervention (with one booster session three months post-intervention) were maintained [74]. On the other hand, significant decreases in depression, stress, and diastolic blood pressure after an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction group (with one booster session six months post-intervention) were lost at two- and three-year follow-up [75].

Physical Health Outcomes.

Mindfulness-based intervention studies also examined physical health outcomes ranging from diabetes-specific (e.g., HBA1C, diabetes meal planning) to more general outcomes such as blood pressure, health-related quality of life, and cortisol. Of the eight mindfulness-based studies that measured HBA1C, the most commonly studied physical outcome, four found a significant reduction post-intervention [45, 51, 52, 54], but only two compared changes to a control condition [51, 52]. In two instances, significant changes in HBA1C were not observed immediately post-intervention but instead at three-month follow-up [51] and one-month follow-up [54]. Of the three studies that examined weight, only one found a significant reduction post-intervention [48]. General health/physical health status was examined in three studies but only significantly changed in one [45, 52]. See Tables 1 and 2 for additional outcomes.

ACT Interventions (six studies)

Psychological Outcomes.

Studies on ACT interventions examined well-being, depression, anxiety, and stress. One study found significant improvement in psychological wellbeing [66]. Of the two that measured depression, one found a significant reduction post-intervention [58]. Of the other outcomes studied, significant changes were found in perceived stress [59] and guilt. Additionally, ACT-related processes, which include acceptance, mindfulness, and values, were measured in two studies, both of which found significant improvements post-intervention compared to the control group [38, 63].

Physical Health Outcomes.

Of the four studies that measured HBA1C, only one found significant reductions post-intervention [63]. One study that did not find a significant reduction in HBA1C post-intervention did find a significant decrease in number of participants with an HBA1C below 7.0 [38]. One of the three studies that measured diabetes self-management found a significant increase post-intervention [63]. In addition, one study found a significant increase in a composite of nutrition, exercise, and alcohol self-efficacy post-intervention [65].

Resilience-Based Interventions (four studies)

Psychological Outcomes.

Resilience was the most commonly studied outcome, examined in three of the studies. However, only one study found a significant improvement in resilience post-intervention [70], and this significant change only occurred at the six-month follow-up and not immediately post-intervention. A significant change in positive meaning was reported in one study [68], and diabetes empowerment increased significantly in another uncontrolled study [69]. Additional well-being specific outcomes including positive affect, quality of life, self-efficacy, and purpose were measured [68, 70], but none showed significant change. Coping strategies, perceived stress, and depression were included as outcomes in two studies [68, 69], but no significant changes were reported in these outcomes.

Physical Health Outcomes.

The most commonly measured physical health outcome was HBA1C, assessed in three studies. Only one found a significant pre-post decrease in HBA1C [69], with no control group for comparison. Across the other three controlled studies, few significant changes were found. One found significant improvement in diabetes knowledge, a decrease in fasting blood glucose, and improvement in HDL cholesterol [68]. Another found a significant decrease in physical activity barriers, though the effect size was small and no longer significant at six-month follow-up [70]. Significant change was not observed for other outcomes, including physical activity, glucose self-monitoring, diet, and waist circumference.

Other Interventions (two studies)

Psychological Outcomes.

Yalcin and colleagues examined the effects of an emotional intelligence intervention (i.e., teaching participants to be better aware of their own and others’ emotional experiences) on well-being and quality of life in individuals with T2D [72]. They found significant improvements post-intervention in emotional intelligence, well-being, and quality of life compared to a wait-list control. Voseckova and colleagues examined an intervention aiming to strengthen positive self-concept and perceived self-efficacy in individuals with T2D [73]. Neither study outcome (psychological state or hardiness), showed significant improvement post-intervention.

Physical Health Outcomes.

A significant change in physical functional status, compared to control, was found following the emotional intelligence intervention [72]. In the study on positive self-concept and self-efficacy, no significant post-intervention change was seen in fasting glucose or HBA1C [73].

Discussion

Our review of well-being interventions for individuals with diabetes yielded a variety of studies and results. Across all studies, interestingly, few well-being-specific outcomes were assessed (i.e., well-being, quality of life, positive affect, self-efficacy). In fact, depression was the most commonly assessed psychological outcome and was significantly improved post-intervention in 14/19 studies. Across intervention types, depression was most consistently studied in, and substantially affected by, mindfulness-based interventions. There were more variable effects on other psychological outcomes (see Table 3 for a summary of results).

Table 3.

Summary of Results

| PP Interventions | Mindfulness-Based | ACT | Resilience-Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| • In select studies, improvements were found in depression, anxiety and several well-being-specific outcomes including positive affect, optimism, gratitude, health-related quality of life with small to medium effect sizes • No significant changes in physical health outcomes were found but trends were seen in improved diabetes self-care behaviors and health behavior adherence |

• Significant changes were seen in well-being-specific outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy, self-compassion, well-being, positive affect, etc.) with small to large effect sizes • Depression was the most frequently studied outcome and consistently showed significant reduction with most reported effect sizes in the medium to large range • HBA1C was the most frequently studied physical health outcome and showed significant changes in two controlled studies |

• Psychological well-being showed significant improvement in one controlled study • ACT-related processes (e.g., acceptance, mindfulness, values) showed improvement with medium to large effect sizes • HBA1C and diabetes self-management were the most frequently studied physical health outcomes and where available, effect sizes were consistently medium to large |

• In select studies, both resilience and positive meaning showed significant improvement with small and medium effect sizes respectively • Significnant changes or positive trends were found in numerous physical health outcomes such as Diabetes Knowledge, Fasting Blood Glucose, HBA1C, Cholesterol, and Blood Pressure with medium to large effect sizes |

Regarding physical health outcomes, HBA1C was the most common outcome measured, with 6/16 studies (three of which were uncontrolled) finding a significant post-intervention effect. Of ten studies that examined health behavior adherence, only four (including two controlled studies) found significant improvement post-intervention. Of the other physical health outcomes studied, no consistent pattern emerged. This lack of consistent findings for physical health outcomes is perhaps not surprising given that many of the well-being interventions did not specifically include behavioral strategies that targeted diabetes self-efficacy or self-management.

The variability in results across the articles is likely explained by several factors. First, there was marked variation in study design, samples, intervention content, and outcomes. The studies included substantially different patient populations (e.g., children and adults, T1D and T2D), considerably varied in culture, race, and ethnicity (especially in the mindfulness-based programs), employed distinct interventions, and used inconsistent outcome measures. In addition, only four studies were rated as high quality. Finally, small sample size (N<50) was common, further contributing to variable and unstable estimates of effect.

Despite these methodological factors, this review suggests that well-being interventions show promise in improving outcomes in persons with diabetes. Many interventions yielded significant improvements in outcomes that are not necessarily well-being constructs but nonetheless are meaningful to patients (e.g., depression, stress), and did so using often simple, short, and potentially cost-effective interventions. We observed some, though lesser, effects on behavioral and medical outcomes, and questions remain about whether well-being interventions alone are enough to result in changes in self-care and outcomes, or whether they are better combined with existing behavioral interventions. Indeed, a small number of studies, including those examining ACT and resilience-based interventions, did pair the intervention of choice with an education or self-efficacy program; these studies were among the highest-rated in terms of quality and had the most consistent effect on physical health outcomes.

This review had several limitations. First, studies in different languages or databases may have been missed. Second, the variable nature of the studies, interventions, and outcomes precluded more quantitative analysis of the interventions’ effects on patient outcomes. Third, overlapping intervention components across intervention categories limited our ability to compare these categories to one another (e.g., one PP intervention included a mindfulness component [41]). Fourth, limitations of individual studies (and relatively low overall study quality) limits conclusions that can be drawn about intervention impact. Finally, additional studies (especially those with negative results) may have been performed but not published, and we were unable to account for publication bias.

In sum, well-being interventions have potential promise in improving psychological and medical outcomes in patients with diabetes, and they are simple and relatively easily delivered in many cases. However, the literature does not yet support definitive recommendations to practitioners about which specific intervention holds the most promise. Rigorous, controlled, and well-powered studies of these interventions, with well-accepted and clinically relevant outcome measures, are needed to ascertain whether well-being interventions can truly impact functioning, diabetes outcomes, and overall health in diabetes. It may also be beneficial to develop consensus for a theoretical model in the literature that can guide the choice of both intervention content and outcome measurement. Finally, future studies should test other intervention delivery options (e.g., mobile health technology) to expand reach, and may consider combining well-being interventions with established interventions targeting specific self-management behaviors to boost overall impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Funding:

This work was supported in part by NIH grant R21DK109313-01 and American Diabetes Association Grant 1-17-ICTS-099 (Huffman PI). The authors have no conflicts of interest to report and there were no other funding sources.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: none

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes: Working to reverse the US epidemic. 2016.

- [2].Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, Wexler DJ, Delahanty L, Wittenberg E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes care. 2007;30:2222–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gonzalez JS, Shreck E, Psaros C, Safren SA. Distress and type 2 diabetes-treatment adherence: A mediating role for perceived control. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2015;34:505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Celano CM, Beale EE, Moore SV, Wexler DJ, Huffman JC. Positive psychological characteristics in diabetes: a review. Current diabetes reports. 2013;13:917–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes care. 2001;24:1069–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li C, Barker L, Ford ES, Zhang X, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Diabetes and anxiety in US adults: findings from the 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2008;25:878–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Niemcryk SJ, Speers MA, Travis LB, Gary HE. Psychosocial correlates of hemoglobin Alc in young adults with type I diabetes. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1990;34:617–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. Journal of diabetes and its complications. 2005;19:113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Aalto AM, Uutela A. Glycemic control, self-care behaviors, and psychosocial factors among insulin treated diabetics: a test of an extended health belief model. International journal of behavioral medicine. 1997;4:191–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Egede LE, Nietert PJ, Zheng D. Depression and all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality among adults with and without diabetes. Diabetes care. 2005;28:1339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang X, Norris SL, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Beckles G, Kahn HS. Depressive symptoms and mortality among persons with and without diabetes. American journal of epidemiology. 2005;161:652–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, et al. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2006;75:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dubois CM, Beach SR, Kashdan TB, Nyer MB, Park ER, Celano CM, et al. Positive psychological attributes and cardiac outcomes: associations, mechanisms, and interventions. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:303–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70:741–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huffman JC, Beale EE, Celano CM, Beach SR, Belcher AM, Moore SV, et al. Effects of Optimism and Gratitude on Physical Activity, Biomarkers, and Readmissions After an Acute Coronary Syndrome: The Gratitude Research in Acute Coronary Events Study. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2016;9:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Boehm JK, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky LD. The prospective association between positive psychological well-being and diabetes. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2015;34:1013–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rose M, Fliege H, Hildebrandt M, Schirop T, Klapp BF. The network of psychological variables in patients with diabetes and their importance for quality of life and metabolic control. Diabetes care. 2002;25:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Papanas N, Tsapas A, Papatheodorou K, Papazoglou D, Bekiari E, Sariganni M, et al. Glycaemic control is correlated with well-being index (WHO-5) in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2010;118:364–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yi JP, Vitaliano PP, Smith RE, Yi JC, Weinger K. The role of resilience on psychological adjustment and physical health in patients with diabetes. British journal of health psychology. 2008;13:311–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Johnston-Brooks CH, Lewis MA, Garg S. Self-efficacy impacts self-care and HbA1c in young adults with Type I diabetes. Psychosomatic medicine. 2002;64:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Al-Khawaldeh OA, Al-Hassan MA, Froelicher ES. Self-efficacy, self-management, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes and its complications. 2012;26:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sousa VD, Zauszniewski JA, Musil CM, Price Lea PJ, Davis SA. Relationships among self-care agency, self-efficacy, self-care, and glycemic control. Research and theory for nursing practice. 2005;19:217–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nakahara R, Yoshiuchi K, Kumano H, Hara Y, Suematsu H, Kuboki T. Prospective study on influence of psychosocial factors on glycemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moskowitz JT, Epel ES, Acree M. Positive affect uniquely predicts lower risk of mortality in people with diabetes. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27:S73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC public health. 2013;13:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, Cuijpers P. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: a meta-analysis. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2010;68:539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Moskowitz JT, Carrico AW, Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Cheung EO, Batchelder A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a positive affect intervention for people newly diagnosed with HIV. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2017;85:409–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Maurer S, Bussolari C, et al. A positive affect intervention for people experiencing health-related stress: development and nonrandomized pilot test. Journal of health psychology. 2012;17:676–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172:322–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z, Wells MT, Wong SC, Hollenberg JP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect induction to promote physical activity after percutaneous coronary intervention. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172:329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Huffman JC, Millstein RA, Mastromauro CA, Moore SV, Celano CM, Bedoya CA, et al. A Positive Psychology Intervention for Patients with an Acute Coronary Syndrome: Treatment Development and Proof-of-Concept Trial. Journal of happiness studies. 2016;17:1985–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33:763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American psychologist. 2001;56:218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Miller SA, Forrest JL. Enhancing your practice through evidence-based decision making: PICO, learning how to ask good questions. Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice. 2001;1:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Seligman ME, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. The American psychologist. 2005;60:410–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kabat-Zinn J Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical psychology: Science and practice. 2003;10:144–56. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2007;75:336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Leppin AL, Bora PR, Tilburt JC, Gionfriddo MR, Zeballos-Palacios C, Dulohery MM, et al. The efficacy of resiliency training programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PloS one. 2014;9:e111420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies. Hamilton, ON: Effective Public Health Practice Project; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, Hult JR, Moskowitz JT. An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. The journal of positive psychology. 2014;9:523–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jaser SS, Patel N, Linsky R, Whittemore R. Development of a positive psychology intervention to improve adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of pediatric health care : official publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners. 2014;28:478–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].DuBois CM, Millstein RA, Celano CM, Wexler DJ, Huffman JC. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Positive Psychological Intervention for Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. The primary care companion for CNS disorders. 2016;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nowlan JS, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, Kinsella JM, Barker G. A Comparison of Single-Session Positive Reappraisal, Cognitive Restructuring and Supportive Counselling for Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Cogn Ther Res. 2016;40:216–29. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dreger LC, Mackenzie C, McLeod B. Feasibility of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Aboriginal Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Mindfulness. 2015;6:264–80. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Haenen S NIvSJPVPF Mindfulness facets as differential mediators of short and long-term effects of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in diabetes outpatients: findings from the DiaMind randomized trial. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2016;85:44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jung HY, Lee H, Park J. Comparison of the effects of Korean mindfulness-based stress reduction, walking, and patient education in diabetes mellitus. Nursing & health sciences. 2015;17:516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Miller CK, Kristeller JL, Headings A, Nagaraja H. Comparison of a mindful eating intervention to a diabetes self-management intervention among adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Health education & behavior : the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2014;41:145–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rungreangkulkij S, Wongtakee W, Thongyot S. Buddhist group therapy for diabetes patients with depressive symptoms. Archives of psychiatric nursing. 2011;25:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Schroevers MJ, Tovote KA, Keers JC, Links TP, Sanderman R, Fleer J. Individual Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for People with Diabetes: a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness. 2013;6:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Friis AM, Johnson MH, Cutfield RG, Consedine NS. Kindness Matters: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Mindful Self-Compassion Intervention Improves Depression, Distress, and HbA1c Among Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2016;39:1963–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gainey A, Himathongkam T, Tanaka H, Suksom D. Effects of Buddhist walking meditation on glycemic control and vascular function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2016;26:92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hartmann M, Kopf S, Kircher C, Faude-Lang V, Djuric Z, Augstein F, et al. Sustained effects of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction intervention in type 2 diabetic patients: design and first results of a randomized controlled trial (the Heidelberger Diabetes and Stress-study). Diabetes care. 2012;35:945–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Rosenzweig S, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, Edman JS, Jasser SA, McMearty KD, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction is associated with improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 2007;13:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Teixeira E The effect of mindfulness meditation on painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in adults older than 50 years. Holistic nursing practice. 2010;24:277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tovote KA, Fleer J, Snippe E, Peeters AC, Emmelkamp PM, Sanderman R, et al. Individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for treating depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes care. 2014;37:2427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Tovote KA, Schroevers MJ, Snippe E, Emmelkamp PMG, Links TP, Sanderman R, et al. What works best for whom? Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes. PloS one. 2017;12:e0179941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].van Son J, Nyklicek I, Pop VJ, Blonk MC, Erdtsieck RJ, Spooren PF, et al. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on emotional distress, quality of life, and HbA(1c) in outpatients with diabetes (DiaMind): a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes care. 2013;36:823–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wagner J, Bermudez-Millan A, Damio G, Segura-Perez S, Chhabra J, Vergara C, et al. Community health workers assisting Latinos manage stress and diabetes (CALMS-D): rationale, intervention design, implementation, and process outcomes. Translational behavioral medicine. 2015;5:415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wagner JA, Bermudez-Millan A, Damio G, Segura-Perez S, Chhabra J, Vergara C, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a stress management intervention for Latinos with type 2 diabetes delivered by community health workers: Outcomes for psychological wellbeing, glycemic control, and cortisol. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2016;120:162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Young LA, Cappola AR, Baime MJ. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction: effect on emotional distress in diabetes. Practical diabetes international : the journal for diabetes care teams worldwide. 2009;26:222–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sasikumar Latheef F. Effects of mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) on stress, depression and mindfulness among type 2 diabetics - A randomized pilot study. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2017;16:654–9. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Shayeghian Z, Hassanabadi H, Aguilar-Vafaie ME, Amiri P, Besharat MA. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes Management: The Moderating Role of Coping Styles. PloS one. 2016;11:e0166599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Nes AA, van Dulmen S, Eide E, Finset A, Kristjansdottir OB, Steen IS, et al. The development and feasibility of a web-based intervention with diaries and situational feedback via smartphone to support self-management in patients with diabetes type 2. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2012;97:385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Moazzezi M, Ataie Moghanloo V, Ataie Moghanloo R, Pishvaei M. Impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Perceived Stress and Special Health Self-Efficacy in Seven to Fifteen-Year-Old Children With Diabetes Mellitus. Iranian journal of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. 2015;9:956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ataie Moghanloo V, Ataie Moghanloo R, Moazezi M. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Depression, Psychological Well-Being and Feeling of Guilt in 7 - 15 Years Old Diabetic Children. Iranian journal of pediatrics. 2015;25:e2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Whitehead LC, Crowe MT, Carter JD, Maskill VR, Carlyle D, Bugge C, et al. A nurse-led education and cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention among adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2017;23:821–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Steinhardt MA, Brown SA, Dubois SK, Harrison L Jr., Lehrer HM, Jaggars SS. A resilience intervention in African-American adults with type 2 diabetes. American journal of health behavior. 2015;39:507–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Steinhardt MA, Mamerow MM, Brown SA, Jolly CA. A resilience intervention in African American adults with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study of efficacy. The Diabetes educator. 2009;35:274–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Bradshaw BG, Richardson GE, Kumpfer K, Carlson J, Stanchfield J, Overall J, et al. Determining the efficacy of a resiliency training approach in adults with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes educator. 2007;33:650–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Rosenberg AR, Yi-Frazier JP, Eaton L, Wharton C, Cochrane K, Pihoker C, et al. Promoting Resilience in Stress Management: A Pilot Study of a Novel Resilience-Promoting Intervention for Adolescents and Young Adults With Serious Illness. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2015;40:992–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Yalcin BM, Karahan TF, Ozcelik M, Igde FA. The effects of an emotional intelligence program on the quality of life and well-being of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes educator. 2008;34:1013–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Voseckova A, Truhlarova Z, Janebova R, Kuca K. Activation group program for elderly diabetic patients. Social work in health care. 2017;56:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].van Son J, Nyklicek I, Pop VJ, Blonk MC, Erdtsieck RJ, Pouwer F. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with diabetes and emotional problems: long-term follow-up findings from the DiaMind randomized controlled trial. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2014;77:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kopf S, Oikonomou D, Hartmann M, Feier F, Faude-Lang V, Morcos M, et al. Effects of stress reduction on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes patients with early kidney disease - results of a randomized controlled trial (HEIDIS). Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2014;122:341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.