Abstract

Approximately 30% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) have hypomagnesemia (blood magnesium (Mg2+) concentration <0.7 mmol/L). In T2D patients, treatment with metformin is associated with reduced blood Mg2+ levels. To investigate how T2D and metformin affect Mg2+ homeostasis db/m and db/db mice were treated with metformin or placebo. Mice were housed in metabolic cages to measure food and water intake, and to collect urine and feces. Serum and urinary Mg2+ concentrations were determined and mRNA expression of magnesiotropic genes was determined in kidney and distal colon using RT-qPCR. Db/db mice had significantly lower serum Mg2+ levels than db/m mice. Mild hypermagnesuria was observed in the db/db mice at two weeks, but not at four weeks. Metformin-treatment had no effect on the serum Mg2+ concentration and on the urinary Mg2+ excretion. Both in kidney and distal colon of db/db mice, there was a compensatory upregulation in the mRNA expression of magnesiotropic genes, such as transient receptor potential melastatin 6 (Trpm6), whereas metformin treatment did not affect gene expression levels. In conclusion, we show that T2D causes hypomagnesemia and that metformin treatment has no effect on Mg2+ homeostasis in mice.

Introduction

Approximately 30% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) have hypomagnesemia (blood magnesium (Mg2+) <0.7 mmol/L)1,2. Hypomagnesemia has serious clinical consequences as it increases the risk of complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, micro and macrovascular disease and foot ulceration3,4. Moreover, Mg2+ deficiency is correlated with insulin resistance, abrogated glucose metabolism and an increased risk of developing T2D5–7. However, the etiology and underlying mechanisms of hypomagnesemia in T2D patients remains largely unknown8.

As Mg2+ is necessary for the activity of over 600 enzymes, it plays numerous vital physiological functions including macromolecule synthesis, energy balance and DNA transcription9. Moreover, Mg2+ stabilizes ATP and is required for its phosphor transfer reactions10.

The intestine and kidney collaboratively regulate Mg2+ balance and maintain its blood concentrations within a narrow range11,12. In the gut, the bulk of Mg2+ absorption occurs in the small intestine via paracellular (passive) transport11. In the colon, the final absorption of Mg2+ takes place by an active transcellular mechanism through transient receptor potential melastatin type 6/7 (TRPM6/TRPM7) cation channels9. In the kidney, 95–99% of filtered Mg2+ is reabsorbed under physiological circumstances9. Approximately 85% of the filtered Mg2+ is reabsorbed paracellularly by the proximal tubule and the thick ascending loop of Henle (TAL), where transport relies on tight junction permeability13,14. Active transport in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) determines the final urinary Mg2+ concentration, as this is the final segment where Mg2+ is reabsorbed15. In physiological conditions, the DCT reclaims 5–10% of filtered Mg2+ transcellularly via TRPM6/7 channels14,16. The expression and/or the activity of TRPM6 is affected by SNPs, dietary Mg2+ intake, drugs and hormones, such as insulin and epidermal growth factor (EGF)14,17–20. SNPs in TRPM6 that impair its response to insulin have been associated with an increased risk of developing T2D and gestational diabetes7,19.

Metformin, the first-line pharmacotherapy in T2D21, suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis and improves insulin sensitivity22. Therefore, its major clinical benefit is reducing blood glucose levels with only a minimal risk of hypoglycemia23,24. The most common side effects of metformin treatment are lactic acidosis, nausea and diarrhea25. Recent cohort studies showed that metformin use in T2D patients is associated with reduced blood Mg2+ levels1,26. However, the mechanism that underlies this correlation has not yet been elucidated. To investigate how T2D and metformin affect Mg2+ homeostasis, control (db/m) and diabetic (db/db) mice were treated with placebo or metformin for four weeks. Serum and urinary electrolytes were measured and mRNA expression of magnesiotropic genes was evaluated in kidney and distal colon.

Methods

Animal study

The animal study was approved by the animal ethics board of the Radboud University Nijmegen (RU DEC 2015-0073) and by the Dutch Central Commission for Animal Experiments (CCD, AVD103002015239). Experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines and in compliance with Dutch and European laws and policies. Twenty diabetic (db/db) and twenty control (db/m) male mice (Charles River, Germany), aged 8–10 weeks, were acclimatized for two weeks in a temperature- and light-controlled room two mice per cage (Eurostandard Type IIL), with ad libitum access to tap water and standard pellet chow. At day 0, diets were changed to a diet containing 0.05% (w/w) MgO (#S9074-E1107, Ssniff Spezialdiäten, GmbH, Germany) and drinking water to demineralized water. At days-2, 12 and 26 mice were housed individually in metabolic cages for 48 hours (24 hours adaptation, 24 hours collection) to measure food and water intake and to collect urine and feces. Mice were weighed twice weekly and blood was collected via the submandibular vein at days -2 and 15. Mice were randomly divided into four experimental groups of ten mice per group, of which half received metformin hydrochloride (0.5 mg/ml, Sigma Aldrich, MI, USA), dispersed in the drinking water. Researchers and animal caretakers were blinded for the metformin treatment. After 28 days of treatment, mice were anaesthetized by 4% (v/v) isoflurane and exsanguinated by orbital sinus bleeding, and death was confirmed by cervical dislocation. Colon and kidney tissues were cleaned with ice-cold PBS and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

RT-qPCR

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands) was used to extract total RNA from kidney and distal colon according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was subjected to DNase (Promega, the Netherlands) treatment at 37 °C for 30 min and then to DNase stop buffer at 65 °C for 10 min. The RNA concentration was measured using the Nanodrop 2000c (Thermoscientific, Wilmington, DE). To synthetize cDNA, 1.5 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed for 1 hour at 37 °C using Moloney-Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands). SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, Veenendaal, the Netherlands) was used to analyze the gene expression levels on a BioRad (Hercules, CA, USA) analyzer. After normalizing to housekeeping gene expression (Hprt), the relative gene expression was calculated by the Livak method (2−∆∆ct). Primers sequences are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for RT-qPCR.

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Cldn10b | GGAGTTCCCCTCCATGCT | GCAAAAATGGAACCGAAAAA |

| Cldn14 | GTCCAGCTCCTAGGCTTCCT | CATCCACAGTCCCTTCAGGT |

| Cldn16 | GTTGCAGGGACCACATTAC | GAGGAGCGTTCGACGTAAAC |

| Cldn19 | GGTTCCTTTCTCTGCTGCAC | CGGGCAACTTAACAACAGG |

| Cnnm4 | TCTGGGCCAGTATGTCTCTG | CACAGCCATCGAAGGTAGG |

| Fxyd2 | TCAGCCTTTCTTGTGACTGG | GGTCTTCCTGTGGCCTCTACT |

| Hprt | TTGCTGACCTGCTGGATTAC | AGTTGAGAGATCATCTCCAC |

| Slc12a1 | CACATGGTCTTCCACTGTGGTT | GGCTCCTCCACACAGGCTC |

| Slc12a3 | CTTCGGCCACTGGCATTCTG | GATGGCAAGGTAGGAGATGG |

| Slc41a1 | CATCCCACACGCCTTCCTGC | CGGCTGGCCTGCACAGCCAC |

| Slc41a3 | TGAAGGGAAACCTGGAAATG | GGTTGCTGCTGATGATTTTG |

| Trpm6 | CTTCACAATGAAAACCTGCCC | AAAGCCATGCGAGTTATCAGC |

| Trpm7 | GGTTCCTCCTGTGGTGCCTT | CCCCATGTCGTCTCTGTCGT |

Cldn10b, claudin 10b; Cldn14, claudin 14; Cldn16, claudin 16; Cldn19, Claudin 19; Cnnm4, cyclin M4; Fxyd2, FXYD-domain containing 2; Hprt, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; Slc12a1, solute carrier family 12 member 1; Slc12a3, solute carrier family 12 member 3; Slc41a1, solute carrier family 41 member 1; Slc41a3, solute carrier family 41 member 3; Trpm6, transient receptor potential melastatin type 6; Trpm7, transient receptor potential melastatin type 7.

Analytical measurements

Serum and urinary Mg2+ concentrations were determined using a spectrophotometric assay (Roche/Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), according to manufacturer’s protocol. Ca2+ concentrations were determined by the o-cresophthalein complexone method. Absorbance for the Mg2+ and Ca2+ assays was measured at 600 nm and 570 nm, respectively, on a Bio-Rad Benchmark plus microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). Serum and urinary Na+ and K+ concentrations were measured at the clinical chemistry department applying standardized methods1. Serum and urinary glucose concentrations were determined by a spectrophotometric assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Instruchemie, Delfzijl, the Netherlands).

Statistical analyses

Interaction between the two main variables (genotype and treatment) was investigated using a two-way ANOVA test. If there was a significant interaction effect, an unpaired multiple t test, with the Holm–Sidak method for multiple comparisons, was used. In the absence of a significant interaction effect, a two-way ANOVA approach with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used. Statistical significance was assessed using Graphpad Prism v7 (La Jolla, CA, USA, RRID: SCR_002798. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

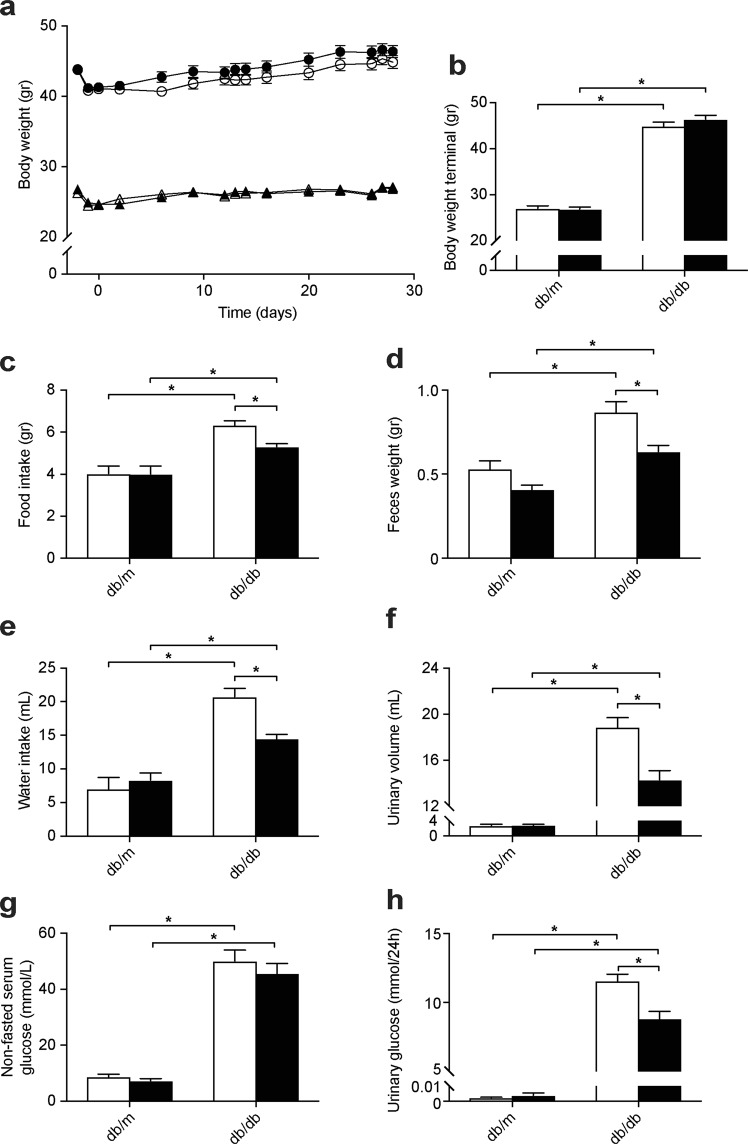

Metformin reduces food intake of db/db mice without affecting body weight

To investigate how T2D and its first-line treatment metformin affect Mg2+ homeostasis, control (db/m) and diabetic (db/db) mice were treated with metformin or placebo for four weeks. Db/db mice were significantly heavier than db/m mice (Fig. 1a,b; 27.0 ± 0.3 vs. 45.6 ± 0.6 gr. for db/m and db/db mice at four weeks, respectively, p ≤ 0.05). Metformin treatment had no effect on body weight in both db/m and db/db mice (Fig. 1a,b). Metformin treatment reduced the food intake only in the db/db mice (Fig. 1c). The lower food intake was accompanied by a decreased feces weight, water intake and urinary volume in the metformin-treated db/db mice (Fig. 1d–f). Metformin did not influence non-fasting serum glucose levels in both genotypes (Fig. 1g). However, the glycosuria of the db/db mice was attenuated by metformin treatment (Fig. 1h).

Figure 1.

Metformin treatment does not affect body weight, but reduces food intake and urinary glucose excretion in db/db mice. Db/m and db/db mice were treated with metformin for four weeks. (a) Body weight of the animals, measured twice weekly and on the days of the metabolic cage experiments. Triangles, db/m mice; circles, db/db mice; open symbols, placebo-treated mice; closed symbols, metformin-treated mice. (b) Body weight at the end of the experiment, after four weeks of treatment. (c) Food intake, (d) total feces weight, (e) water intake and (f) urinary volume determined over a period of 24 hours, using metabolic cages, after four weeks of treatment. (g) Non-fasted serum glucose concentration and (h) 24-hour urinary glucose excretion after four weeks of treatment. Open bars, placebo-treated mice; closed bars, metformin-treated mice. Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between genotype and treatment, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *Indicates a p ≤ 0.05.

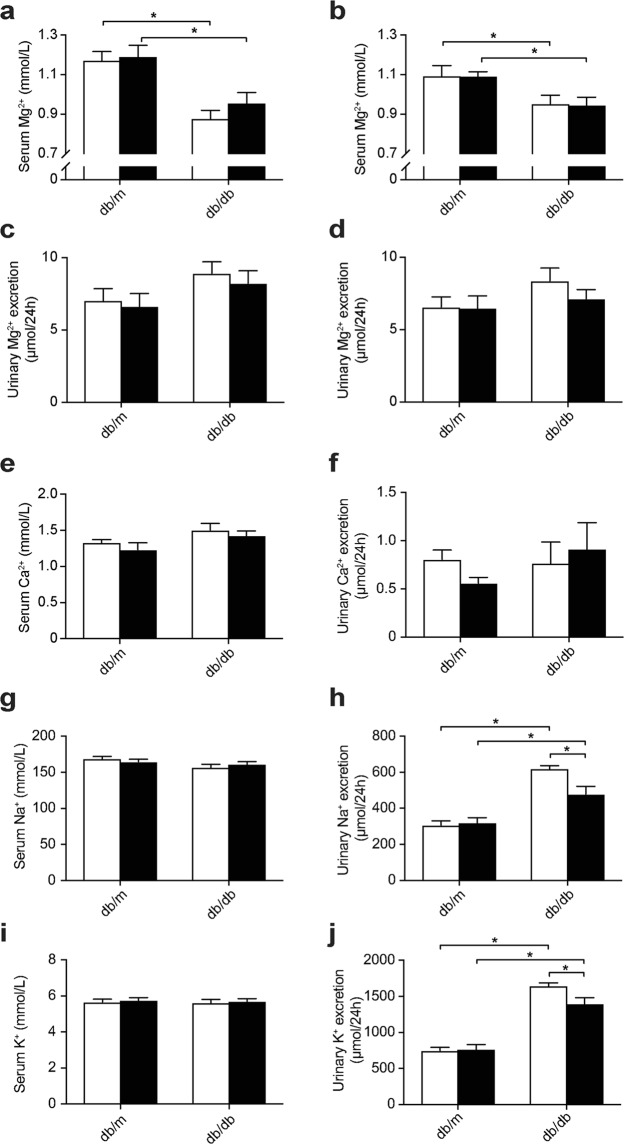

Db/db mice have reduced serum Mg2+ concentrations

Serum Mg2+ concentrations were lower in db/db than db/m mice at two weeks (Fig. 2a, 1.17 ± 0.04 vs. 0.88 ± 0.04 mmol/L in db/m vs. db/db placebo-treated mice, respectively, Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison p ≤ 0.05) and four weeks (Fig. 2b, 1.10 ± 0.05 vs. 0.95 ± 0.04 mmol/L in db/m vs. db/db placebo-treated mice, respectively, Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison p ≤ 0.05). At two weeks, there was a significant genotype effect on urinary Mg2+ excretion, demonstrating an increased urinary Mg2+ loss in db/db mice (Fig. 2c, 6.8 ± 0.6 vs. 8.6 ± 0.6 µmol/24 h in db/m vs. db/db mice, respectively, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05), whereas no significant difference was observed at four weeks (Fig. 2d). At four weeks, the serum Ca2+ concentration was higher in db/db compared to db/m mice, indicated by a significant genotype effect (Fig. 2e, 1.28 ± 0.05 vs. 1.46 ± 0.06 mmol/L Ca2+ in db/m vs. db/db mice, respectively, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05). There were no significant differences on urinary Ca2+ excretion (Fig. 2f). Despite the higher food intake of db/db animals, a significant genotype effect demonstrated lower serum Na+ levels in db/db compared to db/m mice (Fig. 2g, 167 ± 2 vs. 159 ± 3 mmol/L Na+ in db/m vs. db/db mice, respectively, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05). Urinary excretion of Na+ and K+ was higher in db/db than db/m mice, and metformin treatment reduced Na+ and K+ excretion only in db/db mice (Fig. 2h,j). Serum K+ concentrations were not different between all experimental groups (Fig. 2i).

Figure 2.

Db/db mice have a lower serum Mg2+ concentration which is not modulated by metformin treatment. (a) Serum Mg2+ concentration after two weeks of treatment and (b) after four weeks of treatment. (c) 24-Hour urinary Mg2+ excretion after two weeks of treatment (6.8 ± 0.6 vs. 8.6 ± 0.6 µmol/24 h in db/m vs. db/db mice, respectively, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05) and (d) after four weeks of treatment. (e) Serum Ca2+ concentration (1.28 ± 0.05 vs. 1.46 ± 0.06 mmol/L Ca2+ in db/m vs. db/db mice, respectively, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05) and (f) 24-hour urinary Ca2+ excretion, after four weeks of treatment. (g) Serum Na+ concentration (167 ± 2 vs. 159 ± 3 mmol/L Na+ in db/m vs. db/db mice, respectively, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05) and (h) 24-hour urinary Na+ excretion, after four weeks of treatment. (i) Serum K+ concentration and (j) 24-hour urinary K+ excretion, after four weeks of treatment. Open bars, placebo-treated mice; closed bars, metformin-treated mice. Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between genotype and treatment, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *Indicates a p ≤ 0.05.

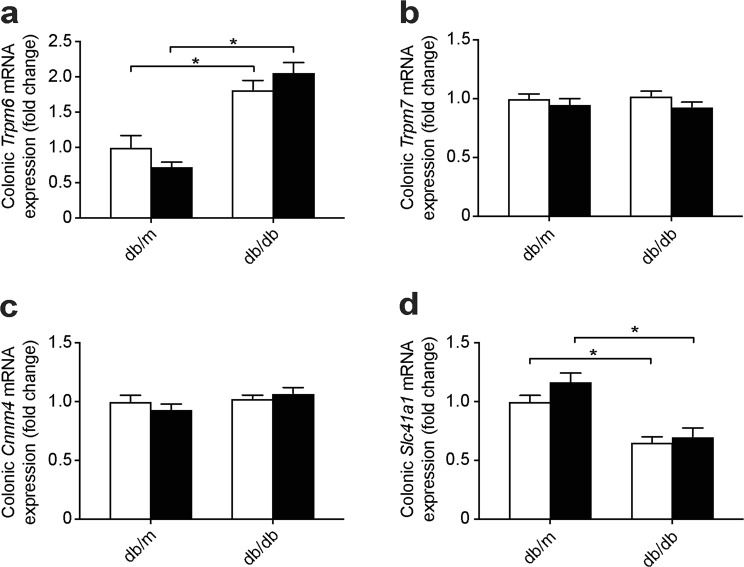

Db/db mice have an enhanced colonic expression of Trpm6

When serum Mg2+ levels decrease, intestinal uptake of Mg2+ is enhanced15. Colonic mRNA expression of Trpm6, the major channel for regulated Mg2+ absorption, was elevated in db/db compared to db/m mice (Fig. 3a). There was no difference in mRNA expression of the ubiquitous Mg2+ channel Trpm7 and of the Mg2+ transport regulator Cyclin m4 (Cnnm4) (Fig. 3b,c). The colonic gene expression of the basolateral Mg2+ transporter solute carrier family 41 (Slc41a1) was lower in both db/db groups (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Upregulation of Trpm6 mRNA expression in the colon of db/db mice. mRNA expression of key magnesiotropic genes in distal colon (a) Trpm6, (b) Trpm7, (c) Cnnm4 and (d) Slc41a1. Open bars, placebo-treated mice; closed bars, metformin-treated mice. Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between genotype and treatment, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *Indicates a p ≤ 0.05.

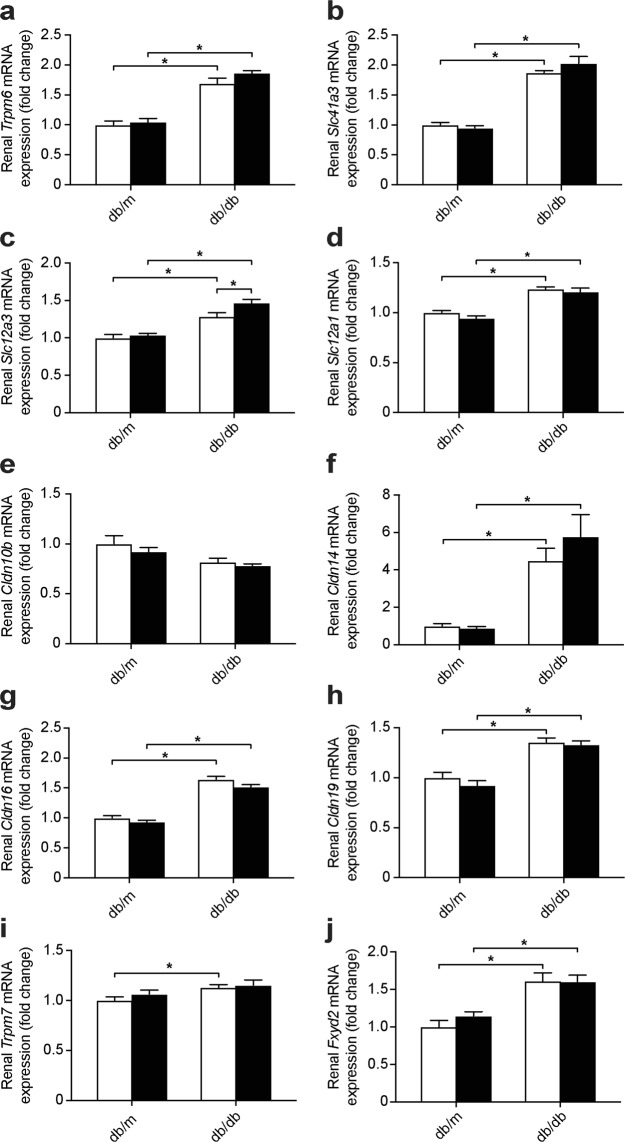

Db/db mice have an elevated renal expression of genes involved in Mg2+ handling

Db/db mice had an enhanced gene expression of the DCT-specific apical Mg2+ channel Trpm6, and the basolateral Mg2+ extruder Slc41a3 (Fig. 4a,b). While both db/db groups showed a higher expression of Slc12a3, encoding for NCC, metformin further enhanced the expression of this gene in db/db mice (Fig. 4c). The driving force for paracellular Mg2+ uptake in the TAL is generated by NKCC2, encoded by Slc12a1, which is expressed higher in db/db mice (Fig. 4d). A significant genotype effect indicated a decreased expression of Claudin 10b (Cldn10b) in db/db mice (Fig. 4e, 1.00 ± 0.05 vs. 0.83 ± 0.02 relative gene expression in db/m vs. db/db mice, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05). In contrast, the mRNA expression of Cldn14, Cldn16 and Cldn19 was enhanced in db/db mice (Fig. 4f–h). The gene expression of the ubiquitous Mg2+ channel Trpm7 was elevated in the placebo-treated db/db mice and the expression of Fxyd2, encoding for the gamma subunit of the Na+-K+-ATPase, was enhanced in both db/db groups (Fig. 4i,j).

Figure 4.

Upregulation in the expression of essential renal magnesiotropic genes in db/db mice. mRNA expression of genes involved in renal electrolyte handling (a) Trpm6, (b) Slc41a3, (c) Slc12a3, (d) Slc12a1, (e) Cldn10b (1.00 ± 0.05 vs. 0.83 ± 0.02 relative gene expression in db/m vs. db/db mice, two-way ANOVA p ≤ 0.05), (f) Cldn14, (g) Cldn16, (h) Cldn19, (i) Trpm7 and (j) Fxyd2. Open bars, placebo-treated mice; closed bars, metformin-treated mice. Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between genotype and treatment, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *Indicates a p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

Hypomagnesemia is a common clinical feature in T2D patients1,3. Metformin use is associated with a lower blood Mg2+ concentration in these patients1,26. In this study, db/db mice developed hypomagnesemia with compensatory upregulation of key renal and colonic magnesiotropic genes. Metformin treatment had no effect on Mg2+ homeostasis in either control or diabetic mice. Our data demonstrate that hypomagnesemia is a consequence of T2D and is not modulated by metformin treatment in mice. INSERT ENTER Metformin is the first-line therapy for T2D27. In large-scale observational cohort studies metformin-use is associated with lower serum Mg2+ levels and reduced renal Mg2+ wasting in T2D patients1,26,28–30. In a small intervention study in T2D patients, metformin treatment resulted in a minor reduction in the serum Mg2+ concentration (from 0.72 to 0.70 mmol/L), despite major improvements in the blood glucose concentration29. In our study, metformin treatment did not affect the serum Mg2+ concentration and urinary Mg2+ excretion in db/db and db/m mice. In addition, metformin did not alter gene expression of colonic and renal Mg2+ transporters. This is in line with a study that observed no effect of a two-week metformin treatment on serum Mg2+ levels in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats31. Possibly, a two- to four-week treatment duration is too short to detect effects on Mg2+ homeostasis. The association between metformin and lower serum Mg2+ levels in T2D patients could also be caused by other factors that were not included in the analyses. For instance, a well-known side effect of metformin-treatment is chronic diarrhea, leading to intestinal malabsorption and hypomagnesemia28.

Hypomagnesemia is prevalent in over 30% of T2D patients32–35. A remaining question is whether hypomagnesemia is the cause or the consequence of T2D8. In the present study, db/db mice developed hypomagnesemia, indicating that hypomagnesemia is a consequence of T2D. At the fourth week of the experiment, db/db mice developed massive glycosuria but no renal Mg2+ wasting. This finding is against the leading hypothesis that renal Mg2+ wasting in T2D patients is a result of glycosuria2,3,36. Indeed, metformin treatment noticeably decreased glycosuria in db/db mice but did not modify the urinary Mg2+ excretion. This is in line with recent observations that glycosuria-causing SGLT2 inhibitors, lead to a mild increase in serum Mg2+ levels37,38. Therefore, it is unlikely that glycosuria underlies hypermagnesuria-induced hypomagnesemia in T2D. As db/db mice develop severe hyperinsulinemia, the observed hypomagnesemia could be a consequence of a Mg2+-shift towards the intracellular compartment, induced by insulin39–41. Future studies should focus on measuring intracellular Mg2+ concentrations in diabetic mice.

The kidneys are essential in maintaining the serum Mg2+ concentration within the physiological range15. The DCT is the final segment where Mg2+ can be reabsorbed9. In the DCT, regulated Mg2+ reabsorption takes place transcellularly via TRPM618. Mg2+ uptake by TRPM6 is dependent on NCC, although the underlying mechanism remains largely unknown42,43. Gene expression levels of Trpm6 and Slc12a3, encoding for NCC, were enhanced in db/db mice, indicative of compensation in the DCT. As only a minor hypermagnesuria is observed at two-weeks, and no hypermagnesuria at four-weeks, there appears to be proper renal compensation in the db/db mice. The TAL is responsible for the bulk of renal Mg2+ reabsorption9. In the TAL, paracellular Mg2+ and Ca2+ reabsorption is regulated by the Cldn14/16/19 complex44,45. Cldn14 mRNA expression is strongly regulated by dietary Ca2+ intake46,47. The high food intake, and therefore high Ca2+ intake, of db/db mice is likely the underlying cause of the extensive upregulation of Cldn14 expression. The high expression of Cldn14 will have a negative effect on Mg2+ reabsorption in the TAL, leading to a compensatory increase in Cldn16/19 expression48. In contrast, gene expression of Cldn10b was decreased. Cldn10b enhances the Na+-permeability of the TAL, and thereby indirectly increases uptake of Mg2+ and Ca2+ in the TAL. Therefore, Cldn10b-deficient mice develop hypermagnesemia and hypomagnesuria. Likely, the observed reduction in Cldn10b expression in the db/db mice is a response to the high osmolality of the pro-urine. INSERT ENTER The strength of this study is that using oral metformin treatment in diabetic mice closely resembles the human situation. Db/db mice developed hypomagnesemia making them an excellent model to study the mechanisms of hypomagnesemia in T2D. Moreover, this study extensively investigated differences in expression of all known genes involved in Mg2+ transport, in both kidney and colon. Some limitations have to be considered. The fact that metformin treatment did not affect Mg2+ homeostasis raises the question whether the dose and duration of metformin treatment were sufficient. However, the metformin treatment reduced the food intake of db/db mice, a known positive effect of metformin. Moreover, the dosage of metformin that the db/db received (0.5 mg/ml, equivalent to a daily intake of approximately 165 mg/kg bodyweight) is similar to previous studies investigating the metabolic effects of metformin in mice49–52. A second limitation is that the expression of genes such as Cldn10b/14, Slc12a1 and Slc12a3 is regulated by both dietary intake and serum levels of K+, Na+ and Ca2+ 43,44,53. As db/db mice have hyperphagia, their dietary intake of ions is also increased. Despite the higher food intake, db/db mice still develop hypomagnesemia. However, for other differences between db/m and db/db mice it is difficult to differentiate whether they are caused by T2D-related factors or by a higher food intake.

In conclusion, hypomagnesemia is a consequence of T2D, which is not affected by metformin treatment. The reason that metformin-users have lower serum Mg2+ concentrations is likely mediated by other factors, and not by a direct effect of metformin on Mg2+ (re)absorption.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maikel School, Janneke Mulders and Jeroen Mooren (Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands) for their excellent technical support. This work was supported by funding from the Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences and by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO VICI 016.130.668 to Joost Hoenderop). Jeroen de Baaij is supported by a grant from the NWO (Veni 016.186.012) and the Dutch Diabetes Research Foundation (2017.81.014). Hacene Bouras is supported by a research fellowship from the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB).

Author Contributions

S.K., H.B., M.K., R.B., J.H. and J.H.F.d.B. conceived and designed the study. S.K., H.B. and C.O.-B. contributed to data acquisition. S.K. and H.B. analyzed the data. All authors interpreted data, drafted the article, revised it and approved the final version.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Steef Kurstjens and Hacene Bouras contributed equally.

References

- 1.Kurstjens S, et al. Determinants of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. European journal of endocrinology. 2017;176:11–19. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mather HM, et al. Hypomagnesaemia in diabetes. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 1979;95:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(79)90364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2007;2:366–373. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02960906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakaguchi Y, et al. Hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetic nephropathy: a novel predictor of end-stage renal disease. Diabetes care. 2012;35:1591–1597. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandeel FR, Balon E, Scott S, Nadler JL. Magnesium deficiency and glucose metabolism in rat adipocytes. Metabolism. 1996;45:838–843. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huerta MG, et al. Magnesium deficiency is associated with insulin resistance in obese children. Diabetes care. 2005;28:1175–1181. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kieboom BCT, et al. Serum magnesium and the risk of prediabetes: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia. 2017;60:843–853. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gommers LM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, de Baaij JH. Hypomagnesemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A Vicious Circle? Diabetes. 2016;65:3–13. doi: 10.2337/db15-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:1–46. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson JE, Chin A. Chelation of Divalent-Cations by Atp, Studied by Titration Calorimetry. Anal Biochem. 1991;193:16–19. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90036-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konrad M, Schlingmann KP, Gudermann T. Insights into the molecular nature of magnesium homeostasis. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2004;286:F599–605. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00312.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chubanov V, Gudermann T, Schlingmann KP. Essential role for TRPM6 in epithelial magnesium transport and body magnesium homeostasis. Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology. 2005;451:228–234. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Regulation of magnesium balance: lessons learned from human genetic disease. Clinical kidney journal. 2012;5:i15–i24. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groenestege WM, Hoenderop JG, van den Heuvel L, Knoers N, Bindels RJ. The epithelial Mg2+ channel transient receptor potential melastatin 6 is regulated by dietary Mg2+ content and estrogens. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2006;17:1035–1043. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rondon LJ, Groenestege WMT, Rayssiguier Y, Mazur A. Relationship between low magnesium status and TRPM6 expression in the kidney and large intestine. Am J Physiol-Reg I. 2008;294:R2001–R2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00153.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlingmann KP, Waldegger S, Konrad M, Chubanov V, Gudermann T. TRPM6 and TRPM7–Gatekeepers of human magnesium metabolism. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1772:813–821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quamme GA, de Rouffignac C. Epithelial magnesium transport and regulation by the kidney. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2000;5:D694–711. doi: 10.2741/A544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thebault S, Alexander RT, Tiel Groenestege WM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. EGF increases TRPM6 activity and surface expression. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2009;20:78–85. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair AV, et al. Loss of insulin-induced activation of TRPM6 magnesium channels results in impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao G, et al. Regulation of the epithelial Mg2+ channel TRPM6 by estrogen and the associated repressor protein of estrogen receptor activity (REA) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14788–14795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808752200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben Sahra I, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene. 2008;27:3576–3586. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rena G, Hardie DG, Pearson ER. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1577–1585. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4342-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foretz M, Guigas B, Bertrand L, Pollak M, Viollet B. Metformin: from mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell metabolism. 2014;20:953–966. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song R. Mechanism of Metformin: A Tale of Two Sites. Diabetes care. 2016;39:187–189. doi: 10.2337/dci15-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheen AJ, Paquot N. Metformin revisited: a critical review of the benefit-risk balance in at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters KE, Chubb SA, Davis WA, Davis TM. The relationship between hypomagnesemia, metformin therapy and cardiovascular disease complicating type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. PloS one. 2013;8:e74355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey CJ. Metformin: historical overview. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1566–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4318-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svare A. A patient presenting with symptomatic hypomagnesemia caused by metformin-induced diarrhoea: a case report. Cases journal. 2009;2:156. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McBain AM, Brown IR, Menzies DG, Campbell IW. Effects of improved glycaemic control on calcium and magnesium homeostasis in type II diabetes. Journal of clinical pathology. 1988;41:933–935. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.9.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dosa MD, Hangan LT, Crauciuc E, Gales C, Nechifor M. Influence of therapy with metformin on the concentration of certain divalent cations in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Biological trace element research. 2011;142:36–46. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ewis SA, Abdel-Rahman MS. Influence of atenolol and/or metformin on glutathione and magnesium levels in diabetic rats. Journal of applied toxicology: JAT. 1997;17:409–413. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1263(199711/12)17:6<409::AID-JAT462>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topf JM, Murray PT. Hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2003;4:195–206. doi: 10.1023/A:1022950321817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simmons D, Joshi S, Shaw J. Hypomagnesaemia is associated with diabetes: Not pre-diabetes, obesity or the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 2010;87:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao WH, et al. Serum and dietary magnesium and the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Archives of internal medicine. 1999;159:2151–2159. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guerrero-Romero F, Rascon-Pacheco RA, Rodriguez-Moran M, de la Pena JE, Wacher N. Hypomagnesaemia and risk for metabolic glucose disorders: a 10-year follow-up study. European journal of clinical investigation. 2008;38:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheehan JP. Magnesium deficiency and diabetes mellitus. Magnes Trace Elem. 1991;10:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert RE, et al. Effects of Canagliflozin on Serum Magnesium in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Post Hoc Analysis of Randomized ControlledTrials. Diabetes therapy: research, treatment and education of diabetes and related disorders. 2017;8:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0232-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang HL, et al. Elevated serum magnesium associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use in type 2 diabetes patients: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Diabetologia. 2016;59:2546–2551. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang DL, Yen CF, Nadler JL. Insulin increases intracellular magnesium transport in human platelets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:549–553. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.3.8445010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi K, et al. The db/db mouse, a model for diabetic dyslipidemia: molecular characterization and effects of Western diet feeding. Metabolism. 2000;49:22–31. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(00)90588-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koranyi L, James D, Mueckler M, Permutt MA. Glucose transporter levels in spontaneously obese (db/db) insulin-resistant mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1990;85:962–967. doi: 10.1172/JCI114526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viering D, de Baaij JHF, Walsh SB, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D. Genetic causes of hypomagnesemia, a clinical overview. Pediatric nephrology. 2017;32:1123–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3416-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nijenhuis T, et al. Enhanced passive Ca2+ reabsorption and reduced Mg2+ channel abundance explains thiazide-induced hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI24134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milatz S, et al. Mosaic expression of claudins in thick ascending limbs of Henle results in spatial separation of paracellular Na+ and Mg2+ transport. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:E219–E227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611684114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou J. Claudins and mineral metabolism. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 2016;25:308–313. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plain A, et al. Corticomedullary difference in the effects of dietary Ca2+ on tight junction properties in thick ascending limbs of Henle’s loop. Pflug Arch Eur J Phy. 2016;468:293–303. doi: 10.1007/s00424-015-1748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dimke H, et al. Activation of the Ca(2+)-sensing receptor increases renal claudin-14 expression and urinary Ca(2+) excretion. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2013;304:F761–769. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00263.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong YF, et al. Claudin-14 regulates renal Ca++ transport in response to CaSR signalling via a novel microRNA pathway. Embo J. 2012;31:1999–2012. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eskens BJ, Zuurbier CJ, van Haare J, Vink H, van Teeffelen JW. Effects of two weeks of metformin treatment on whole-body glycocalyx barrier properties in db/db mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou M, et al. Protective effect of metformin in CD1 mice placed on a high carbohydrate-high fat diet. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foretz M, et al. Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice independently of the LKB1/AMPK pathway via a decrease in hepatic energy state. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:2355–2369. doi: 10.1172/JCI40671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anisimov VN, et al. Metformin extends life span of HER-2/neu transgenic mice and in combination with melatonin inhibits growth of transplantable tumors in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:188–197. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.1.10407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haque MZ, Ares GR, Caceres PS, Ortiz PA. High salt differentially regulates surface NKCC2 expression in thick ascending limbs of Dahl salt-sensitive and salt-resistant rats. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2011;300:F1096–1104. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00600.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.