Abstract

A peroxidase catalyzes the oxidation of a substrate with a peroxide. The search for peroxidase-like and other enzyme-like nanomaterials (called nanozymes) mainly relies on trial-and-error strategies, due to the lack of predictive descriptors. To fill this gap, here we investigate the occupancy of eg orbitals as a possible descriptor for the peroxidase-like activity of transition metal oxide (including perovskite oxide) nanozymes. Both experimental measurements and density functional theory calculations reveal a volcano relationship between the eg occupancy and nanozymes’ activity, with the highest peroxidase-like activities corresponding to eg occupancies of ~1.2. LaNiO3-δ, optimized based on the eg occupancy, exhibits an activity one to two orders of magnitude higher than that of other representative peroxidase-like nanozymes. This study shows that the eg occupancy is a predictive descriptor to guide the design of peroxidase-like nanozymes; in addition, it provides detailed insight into the catalytic mechanism of peroxidase-like nanozymes.

The search for peroxidase-like as well as other enzyme-like nanozymes mainly relies on trial-and-error strategies, due to the lack of predictive descriptors. Here, the authors fill this gap by investigating the occupancy of eg orbitals as a possible descriptor for the peroxidase-like activity of transition metal oxide nanozymes

Introduction

Artificial enzymes aim to imitate the unique catalytic activities of natural enzymes using alternative materials. Recently, functional nanomaterials with enzyme-like catalytic activities, called nanozymes, have emerged as promising alternatives that could overcome the low stability and high cost of natural enzymes1–13. Intriguingly, nanozymes are superior to molecular and polymeric enzyme mimics in several ways, such as their tunable catalytic activities, large surface areas for bioconjugation, and multiple functionalities in addition to catalysis14. Among different nanozymes, enormous efforts have been devoted to developing nanomaterials with peroxidase-like activity (i.e., ) because of their broad applications, which range from biomedical diagnosis and bioimaging to antibacterial agents and antibiofouling coatings for medical devices1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 14–18.

Many nanomaterials, including systems based on various transition metal oxides (TMOs), have been explored as possible peroxidase mimics14. For example, Yan and colleagues1, 2, 19 discovered the unexpected peroxidase-like activity of iron oxide nanoparticles, which were then applied to Ebola detection and tumor immunostaining. We have recently developed Ni oxide-based peroxidase mimics for glucose detection in serum20. However, these peroxidase-like nanozymes are generally developed using trial-and-error strategies14. The prevalence of empirical approaches is due to the lack of predictive descriptors—structural characteristics of the nanomaterials that can be used as proxies for their peroxidase-like activities. This lack of predictive descriptors significantly hampers the identification of more active nanozymes.

Recently, several studies have demonstrated that for electrocatalysis and photocatalysis, the d-band center of metals, O 2p-band center of TMOs, and eg occupancy of TMOs serve as suitable activity descriptors to design efficient electro- and photo-catalysts, respectively21–38. However, the activity descriptors of the enzyme-mimicking nanocatalysts (e.g., peroxidase-like nanozymes) remain largely unknown39.

In this study, we aim to identify a predictive descriptor for TMO-based peroxidase mimics. We reason that the eg occupancy (i.e., the d-electron population of the eg (σ*) antibonding orbitals associated with the transition metal sites) may control the peroxidase-like activity of perovskite TMOs because of the central role of oxygen species in these biomimetic catalytic reactions. We choose ABO3-type perovskite TMOs with BO6 octahedral subunits (where A is a rare earth or alkaline-earth metal and B is a transition metal) as a model system due not only to their low cost and ease of preparation, but, more importantly, also to their diverse and controllable structural and catalytic properties (Fig. 1a)24, which may facilitate the tuning of the eg occupancy by adjusting the ABO3 composition. We show that the peroxidase-like activity of ABO3-type perovskite TMOs is primarily governed by their eg occupancy. In particular, we identify a volcano relationship between the eg occupancy and the specific catalytic activity of perovskite TMO-based peroxidase mimics: namely, perovskite TMOs with an eg occupancy of ~1.2 and 0 (or 2) exhibit the highest and the lowest peroxidase-like activity, respectively. These conclusions are further rationalized by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The identified descriptor successfully predicts the peroxidase-like activity of binary TMOs with octahedral coordination geometries.

Fig. 1.

Fe-based perovskite TMOs as peroxidase mimics. a Schematic of ABO3 perovskite structure. A (rare earth or alkaline-earth metal), B (transition metal), and O are shown in gray, blue, and yellow, respectively. b 3d electron occupancy of t2g (π*) and eg (σ*) antibonding orbitals associated with the transition metal, for LaFeO3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO3-δ, and SrFeO3-δ. c TEM image of LaFeO3. Scale bar: 200 nm. d PXRD patterns of LaFeO3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO3-δ, and SrFeO3-δ (the red lines at the bottom mark the reference pattern of LaFeO3 from the JCPDS database, card number 75-0541). e Typical absorption spectra of 0.8 mM TMB after catalytic oxidation with 50 mM H2O2 in pH 4.5 acetate buffer at 40 °C, in the presence of 10 μg mL−1 of LaFeO3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO3-δ, and SrFeO3-δ nanozymes. f Time evolution of absorbance at 652 nm (A652) for monitoring the catalytic oxidation of 1 mM TMB with 100 mM H2O2 in the presence of 10 μg mL−1 of LaFeO3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO3-δ, and SrFeO3-δ nanozymes. g Specific peroxidase-like activities of LaFeO3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO3-δ, and SrFeO3-δ. h Specific peroxidase-like activity of the Fe-based perovskite TMOs as a function of eg occupancy. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Results

Identification of nanozyme activity descriptor

The perovskite samples were prepared by a sol-gel method followed by annealing at the desired temperatures. The as-prepared perovskites were fully characterized by scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM), powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area measurements (see Supplementary Figs 1–13 and Supplementary Tables 1–2 for details). The amount of oxygen vacancies in the perovskites was quantified by iodometric titrations (Supplementary Table 3). To identify a suitable descriptor for the peroxidase-like activity of perovskite TMOs, we initially examined La1-xSrxFeO3-δ compositions (x = 0–1), because the eg occupancy of Fe in this series of perovskites could be gradually tuned by substituting La3+ with Sr2+ cation (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 4). Such a substitution would shift the oxidation state of Fe from + 3 in LaFeO3 to + 3.31 in SrFeO3-δ, resulting in the corresponding change of the eg occupancy of Fe from 2 to 1.69 (note: as there are no fractional electrons occupying these orbitals, the eg occupancies presented in the current study are averages between integer occupations). A representative TEM image of LaFeO3 (Fig. 1c) reveals the typical irregular morphology of perovskites with nanoscale features. The formation of phase-pure La1-xSrxFeO3-δ (x = 0, 0.5, and 1) perovskite structures was confirmed by matching their PXRD data to the standard pattern of LaFeO3 (JCPDS card number 75-0541) (Fig. 1d).

The peroxidase-like activity of the perovskite-based nanozymes was assessed by using absorption spectroscopy to monitor the catalytic oxidation of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, a typical peroxidase substrate) with H2O2 in the presence of the nanozymes. The oxidation of TMB generates an oxidized product (oxTMB) with a characteristic absorption peak at 652 nm. The intensity of this absorption peak (A652) increased with increasing Sr content and the highest absorption was obtained for SrFeO3-δ (Fig. 1e). The time evolution of the A652 value (Fig. 1f) shows that SrFeO3-δ also exhibited the fastest reaction kinetics, demonstrating that the Sr substitution effectively enhanced the peroxidase-like activity of La1-xSrxFeO3-δ. The mass-based peroxidase-like activities of nanozymes were measured by steady-state kinetics assays (see Methods section). To separate the effect of surface area from the intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of perovskites (including the Fe-based perovskites discussed in this section), their specific activity (i.e., the mass activity normalized to the surface area) was also calculated, based on the BET surface areas obtained by nitrogen desorption measurements (Supplementary Figs 3 and 6, and Supplementary Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1g, the specific activity of SrFeO3-δ was 7.76 and 1.79 times higher than that of LaFeO3 and La0.5Sr0.5FeO3-δ, respectively. The dependence of the specific activity on the Sr content of La1-xSrxFeO3-δ and the eg occupancy of Fe is plotted in Fig. 1h. A substantial improvement in the peroxidase-like activity of La1-xSrxFeO3-δ was observed as the Sr content increased from 0 to 1 and the eg occupancy of Fe decreased from 2 to 1.69.

To study the effect of eg occupancy lower than 1 on the peroxidase-like activity of perovskites, we investigated three Mn-based perovskites with the eg occupancy of Mn varying from 0.68 to ~0.08 (i.e., eg = 0.68, 0.53, and 0.08 for LaMnO3-δ, La0.5Sr0.5MnO3-δ, and CaMnO3-δ, respectively). The SEM and TEM images shown in Supplementary Figs 4 and 5, and the PXRD patterns in Supplementary Fig. 7a demonstrate the successful synthesis of the Mn-based perovskites. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7c, the specific activity of LaMnO3-δ was 1.42 and 43.29 times higher than that of La0.5Sr0.5MnO3-δ and CaMnO3-δ, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 7e shows the effect of the eg occupancy on the specific peroxidase-like activity of the Mn-based perovskites. Different from the trend observed for the Fe-based perovskites (i.e., the peroxidase-like activity increased as the eg occupancy decreased), the catalytic activity of the Mn-based perovskites decreased as the eg occupancy further decreased from 0.68 to ~0.08. Taken together, the above results show a strong but non-monotonic correlation between eg occupancy and peroxidase-like activity of perovskites, suggesting the eg occupancy as a potential activity descriptor.

Evaluation of eg occupancy as nanozyme activity descriptor

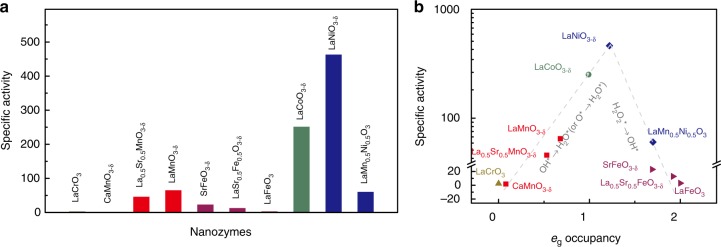

To further evaluate the correlation between the eg occupancy and their peroxidase-like activity, overall ten perovskite TMOs covering eg occupancies of 0–2, six as described above and four others (i.e., LaCrO3, LaCoO3-δ, LaNiO3-δ, and LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3) were investigated (Supplementary Figs 8–14, Supplementary Table 6, and Supplementary Notes 1–2). As shown in the summary in Fig. 2a, the perovskite TMOs exhibited significantly different specific peroxidase-like activities. Some of them (such as LaNiO3-δ) exhibited a high activity, whereas the activity of others (such as LaCrO3) was negligible. This behavior can be understood by plotting the activities of the ten perovskite TMOs as a function of the corresponding eg occupancy associated with the B cations: a definitive volcano relationship is obtained (Fig. 2b). The mass-based peroxidase-like activities (i.e., mass activities) of the perovskite TMOs also show a volcano dependence on the corresponding eg occupancies (Supplementary Fig. 15), confirming that the catalytic activity of the perovskite TMO-based peroxidase mimics is primarily governed by the eg occupancy of the B cations. In particular, perovskite TMOs with eg occupancy of ~1.2 exhibit the highest peroxidase-like activity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of eg occupancy as an effective descriptor for catalytic activity of perovskite TMO-based peroxidase mimics. a Specific peroxidase-like activities of perovskite TMOs. b Specific peroxidase-like activities of perovskite TMOs plotted as a function of eg occupancy, in which equations shown in gray are the rate-limiting reaction steps (note: the rate-limiting steps of the catalytic reaction would be discussed in DFT calculations section). The two lines are shown for eye-guiding only. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Evaluation of other parameters as potential descriptors

As several other potential descriptors (i.e., oxidation state of transition metal, 3d electron number of B-site ions, O 2p-band center, and B-O covalency) have been studied to predict the electrocatalytic and photocatalytic activities of perovskites, we also investigated the relationship between the peroxidase-like activity and these parameters. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, although the oxidation state of B sites affects the peroxidase-like activity of perovskites, there is no apparent relationship between them. These results indicated that the oxidation state of B sites is not an effective descriptor and cannot provide guidance for the rational design of peroxidase-like nanozymes. We then studied the relationship between the peroxidase-like activity and the 3d electron number of B-site ions. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 17, an “M-shaped” relationship with the maximum peroxidase-like activities around d4 and d7 was obtained. Clearly, although the 3d electron number is indicative, it is not a straightforward descriptor, as two maxima are associated with it. Several recent studies suggested that the O 2p-band center could be a better activity descriptor than the eg occupancy to design catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction and oxygen evolution reaction33, 34, 40; therefore, we also evaluated it as a potential descriptor for the peroxidase-like activity of perovskites (Supplementary Note 6). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, the O 2p-band center was not well correlated with the peroxidase-like activity of perovskites, suggesting that it is not an effective descriptor for the perovskite-based peroxidase mimics. Last, we studied the relationship between the peroxidase-like activity and B-O covalency. The B-O covalency was approximately quantified by the normalized O 1s → B 3d – O 2p absorbance from O K-edge X-ray absorption spectra21. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 19, there is no apparent relationship between the B-O covalency and the peroxidase-like activity of the six representative perovskites. Interestingly, for the perovskites with eg occupancy close to 1 (i.e., LaMnO3-δ, LaCoO3-δ, and LaNiO3-δ), their peroxidase-like activity increases with the increasing of covalency strength of B-O. These results suggested that the B-O covalency may act as a secondary descriptor for peroxidase-like activity when the eg occupancy of B-site is close to 1 (Supplementary Note 3).

In short, in contrast to the eg occupancy, none of the four parameters discussed in this section showed a volcano relationship with the peroxidase-like activity of perovskites. These results further validated that the eg occupancy as an effective activity descriptor to predict the peroxidase-like activity of perovskites.

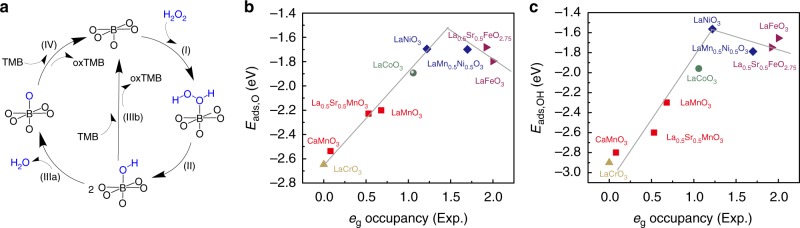

DFT calculations

To theoretically explain the effect of eg occupancy on the peroxidase-like activity, we performed DFT calculations for 11 ABO3 perovskites (i.e., LaCrO3, CaMnO3, La0.5Sr0.5MnO3, LaMnO3, LaCoO3, LaNiO3, SrFeO3, LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO2.75, LaFeO3, and La0.5Sr0.5FeO3) and proposed molecular mechanisms for the activities. The calculated geometric parameters and eg occupancy values for these bulk structures generally agreed with the experimental ones (Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary Figs 20–22). We proposed that these perovskites mimicked peroxidases via mechanisms of Fig. 3a: (1) the adsorption (I) and dissociation (II) of H2O2 molecules on ABO3 surfaces to generate the OH adsorption species; (2) the conversion of these OH adsorption species to O adsorption species, which subsequently oxidize TMB substrates (IIIa and IV); (3) or alternatively, the direct oxidization of TMB by the OH adsorption species (IIIb). Perovskite ABO3 (001) surfaces with the BO2 termination were selected as the surfaces of reactions, because transition metal B in these surfaces are all five coordinated and each has one open coordination site. The five coordinated BO2 termination is analogous to metals in metalloporphyrins, the active centers of many natural enzymes. The adsorption of H2O2 on perovskite (001) surfaces has no energy barriers (Supplementary Fig. 23), suggesting step I does not determine the overall reaction rate. The variations of absorption energies (Eads) for O (Eads,O) and OH (Eads,OH) with respect to eg occupancy are shown in Fig. 3b, c, and that for H2O2 () in Supplementary Fig. 24. Volcano-like relationships were found for Eads,O and Eads,OH with eg occupancy (Fig. 3b and c and Supplementary Fig. 24). Further analysis shows that the five perovskites with eg occupancy < 1.2 (i.e., LaCrO3, CaMnO3, La0.5Sr0.5MnO3, LaMnO3, and LaCoO3) have strong OH* and O* adsorption energies; the other five perovskites with eg occupancy > 1.2 (i.e., LaMn0.5Ni0.5O3, SrFeO3, La0.5Sr0.5FeO2.5, La0.5Sr0.5FeO3, and LaFeO3) as well as LaNiO3 have weak OH* and O* adsorption energies. Perovskites with eg occupancy of ~1.2 have the weakest O and OH adsorption, in which the transfer of these oxygen species to TMB substrates is the easiest, in agreement with their highest peroxidase-mimicking activities. However, LaFeO3 with negligible peroxidase-like activity also possesses weak O and OH adsorption. Therefore, we reasoned that the oxidation of the substrate (i.e., IIIb and IV of Fig. 3a) is not the only rate-determining step. Reportedly, when a kinetic profile goes through a maximum as a function of a given parameter, it means that there is a change of the rate-determining step governing the reaction mechanism32. To identify all the rate-determining steps and to validate the mechanisms of Fig. 3a, we further calculated the energies for species involved in the proposed reaction pathways (Supplementary Figs 23–25). Supplementary Fig. 25 plots the energies of species involved in the proposed reaction pathways. It reveals that for the five perovskites with eg occupancy < 1.2, which are all located on the left side of Fig. 2b’s volcano-like plots, the rate-determining step should be the oxidation of the substrate (i.e., IIIb and IV of Fig. 3a); for the other five with eg occupancy > 1.2, which are all located on the right side of the volcano-like plots, the rate-determining step should be the O–O bond splitting of the adsorbed H2O2* (II of Fig. 3a); LaNiO3 is the maximum point where the rate-determining step changes. Taking these results together, eg occupancy influences the peroxidase-mimicking activities of perovskites by altering the Eads of reaction intermediates and the rate-determining step governing the catalytic reactions. Perovskites with eg occupancy of ~1 possess optimal Eads and can facilitate these rate-determining steps efficiently, which further lead to the high peroxidase-like activity.

Fig. 3.

Computational analysis of the peroxidase-mimicking activity of ABO3 perovskite TMOs. a Proposed sub-processes responsible for the oxidation of TMB to oxTMB with the (001) facet of ABO3 as peroxidase mimics. b, c Adsorption energies of O (Eads,O) and OH (Eads,OH) plotted as a function of eg occupancy, where Eads and eg occupancy were obtained by calculations and experiments, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

General applicability of the eg occupancy

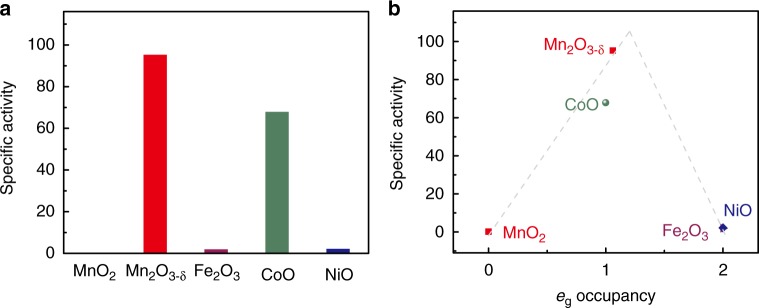

To test whether eg occupancy could also predict the activity of non-perovskites TMOs with the same metal-oxygen octahedral coordination geometry as the perovskites described above, we investigated the peroxidase-like activity of five binary metal oxide nanoparticles (Supplementary Figs 26–28, Supplementary Table 7, and Supplementary Note 4). First, to demonstrate the predictive power of the descriptor, CoO and Mn2O3-δ nanoparticles with unit eg occupancy were tested, as their peroxidase-like activities are unknown. If the eg occupancy descriptor was also applicable to the binary metal oxides, these nanoparticles would be expected to exhibit high peroxidase-like activities. As shown in Supplementary Figs 29, 30a and Fig. 4a, both nanoparticles exhibited excellent activities, in agreement with the prediction based on the eg occupancy descriptor. By contrast, the measured peroxidase-like activities of MnO2 (eg = 0), Fe2O3 (eg = 2), and NiO (eg = 2) nanoparticles were nearly negligible (Supplementary Fig. 29 and Fig. 4a), again in agreement with the prediction. These results clearly demonstrate that the peroxidase-like activity of binary metal oxides with octahedral coordination geometry is similarly associated with the eg occupancy, with a similar volcano dependence to that obtained for the perovskite TMO-based peroxidase mimics (Supplementary Fig. 30b and Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Binary TMOs as peroxidase mimics. a Specific peroxidase-like activities of MnO2, CoO, Mn2O3-δ, NiO, and Fe2O3. b Specific peroxidase-like activities of the binary metal oxides as a function of eg occupancy. The two lines are shown for eye-guiding only. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

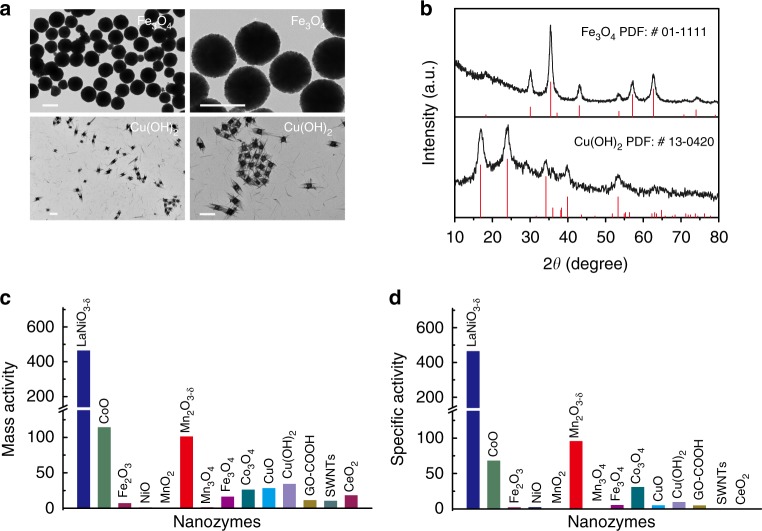

Comparison with other peroxidase mimics

Among the 16 TMOs studied in this work (Figs 2, 4 and Supplementary Fig. 10), LaNiO3-δ was identified as the most active peroxidase mimic, in terms of both specific and mass activities (Supplementary Note 5). Over the last decade, dozens of nanomaterials have been proposed as peroxidase mimics41. A comparison between the nanozymes developed in this work and those reported in the literature may be useful for searching for new nanozymes. However, a direct comparison between data produced by different studies is difficult, because the applied protocols or even the specific test conditions, such as temperature and H2O2 concentration, could significantly influence the peroxidase-like activity of the nanomaterials. To allow for a reliable and rigorous comparison, we synthesized several peroxidase mimics reported in previous studies (Fig. 5, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figs 26–28, 31–32, and Supplementary Table 5) and compared their peroxidase-like activities with that of LaNiO3-δ under the same conditions. Fe3O4 nanoparticles and Cu(OH)2 supercages were chosen as representative peroxidase mimics for comparison: Fe3O4 nanoparticles were the first reported peroxidase mimics, whereas Cu(OH)2 supercages are the state-of-the-art representatives of these systems, with Kcat (catalytic constant) values comparable to those of natural peroxidase1, 42. Fig. 5a,b confirm the successful preparation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles and Cu(OH)2 supercages. The time evolution of the A652 parameter (Supplementary Fig. 33 and Fig. 5c) shows that the mass activity of LaNiO3-δ is 28.9 and 13.6 times higher than that of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and Cu(OH)2 supercages, respectively. Moreover, Fig. 5d shows that the specific activity of LaNiO3-δ was 91.4 and 49.0 times higher than that of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and Cu(OH)2 supercages, respectively, because of the smaller surface area of the LaNiO3-δ nanoparticles prepared by the sol-gel method. Other representative nanozymes (such as CeO2, CuO, single-walled carbon nanotubes, and graphene oxide (GO-COOH)) were also investigated. The results in Fig. 5c,d confirm the superior performance of LaNiO3-δ, in terms of both specific and mass activity, further demonstrating the power of the eg occupancy descriptor for identifying nanozymes of particularly high activity.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of peroxidase-like activity of LaNiO3-δ and other nanozymes. a Representative TEM images of Fe3O4 and Cu(OH)2 at different magnifications. Scale bars: 500 nm. b PXRD patterns of Fe3O4 and Cu(OH)2 (the red lines mark the reference patterns of Fe3O4 (JCPDS card number 01-1111) and Cu(OH)2 (JCPDS card number 13-0420)). c Mass-normalized peroxidase-like activities of LaNiO3-δ and other nanozymes. d Specific peroxidase-like activities of LaNiO3-δ and other nanozymes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Discussion

Using experimental measurements and DFT calculations, we have identified the eg occupancy as a predictive and effective descriptor for the peroxidase-like activity of TMO (including perovskite TMO) nanomaterials. The catalytic activity of peroxidase-like nanozymes with metal-oxygen octahedral coordination geometry shows a volcano dependence on the eg occupancy. Namely, nanozymes with eg occupancy of ~1.2 had the highest catalytic activity, whereas eg occupancies of 0 or 2 corresponded to negligible activities. The systematic comparison of more than 20 representative peroxidase-like nanozymes revealed that LaNiO3-δ had the highest catalytic activity. Besides supporting an approach to the design of highly active peroxidase mimics based on the eg occupancy, the present study also provided deep insight into the catalytic mechanism of the peroxidase-like activity of the nanozymes. Taking into account the adaptable structures and catalytic activities of TMO-based nanozymes, the current study has prompted us to further explore the application of the eg occupancy descriptor to predict the enzyme-like activities of other metal oxides.

Methods

Synthesis of perovskite TMOs

The perovskite TMOs were synthesized via a sol-gel method43. Briefly, the respective metal nitrate salts in appropriate stoichiometric ratios (3 mmol in total) and citric acid (12 mmol) were dissolved in 100 mL of H2O, followed by the addition of 1.5 mL of ethylene glycol. The resulting transparent solutions were treated at 90 °C under stirring to condense them into gel, which were then decomposed at 180 °C for 5 h to form the solid precursors. The latter were decomposed at 400 °C for 2 h to remove the organic components and obtain foam precursors, which were further annealed at 700 °C (850 °C in the case of CaMnO3-δ) for 5 h with a ramp rate of 5 °C min−1, to obtain the final perovskite TMOs.

Structure characterization

PXRD data were collected at room temperature using a Rigaku Ultima diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. The diffractometer was operated at 40 kV and 40 mA, with a scan rate of 5° min−1 and a step size of 0.02°. TEM images were recorded on a JEOL JEM-2100 or FEI Tecnai F20 microscope at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. SEM measurements were performed on a Hitachi S-4800 microscope operated at 5 kV. UV-visible absorption spectra were collected using a spectrophotometer (TU-1900, Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co. Ltd, China). Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured at 77 K using a Quantachrome Autosorb-IQ-2C-TCD-VP analyzer and were used to calculate the surface areas of the nanozymes with the BET method. The temperature-dependent magnetization was measured on a MPMS SQUID magnetometer (MPMS-3, Quantum Design) with a magnetic field of H = 1 kOe under field-cooling procedures. O K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements were performed at the beamline BL12B-a (CMD) in Hefei Synchrotron Radiation Facility, National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory.

Peroxidase-like activity measurements

Steady-state kinetics assays were conducted at 37 °C in 1.0 mL cuvettes with a path length of 0.2 cm. A 0.2 M NaOAc buffer solution (pH 4.5) was used as the reaction buffer and 10 μg mL−1 of nanozymes were used for their kinetics assays. The kinetics data were obtained by varying the concentration of H2O2 while keeping the TMB’s concentration constant (Supplementary Table 8). The kinetics constants (i.e., vmax and Km) were calculated by fitting the reaction velocity values and the substrate concentrations to the Michaelis–Menten equation as follows:

| 1 |

where v is the initial reaction velocity and vmax is maximal reaction velocity. vmax is obtained under saturating substrate conditions. [S] is the substrate concentration. Km, the Michaelis constant, equals to the concentration of substrate when the initial reaction velocity reaches half of its maximal reaction rate. As for TMOs with negligible activity (i.e., LaCrO3, LaFeO3, CaMnO3-δ, NiO, MnO2, and Mn3O4), we assumed the initial reaction velocity in the presence of 10 μg mL−1 of nanozymes, 1 mM TMB, and 100 mM H2O2 as the vmax, because the kinetics measurements for them were difficult and not reliable.

The mass activities of the nanozymes were defined as follows:

| 2 |

The specific activities of the nanozymes were calculated from Eqs (3) and (4):

| 3 |

| 4 |

DFT calculations

The bulk structure of each defect-free perovskite was modeled using the A8B8O24 unit cell, which was sufficiently large to consider all possible G-type antiferromagnetic (G-AFM), A-type antiferromagnetic (A-AFM), and paramagnetic (PM) magnetic orderings previously reported for perovskites (Supplementary Fig. 20). Geometrically relaxed ground-state bulk structures were then used to build the (001) slabs, each of which contained six layers: three AO and three BO2 (Supplementary Fig. 21). For geometry optimizations of bulks, their space group symmetries (Supplementary Table 9) were used to constrain the geometries. For geometry optimizations using slab models, atoms in the bottom two layers (i.e., one AO and one BO2 layer) were frozen and those in the above layers were allowed to move; lattice parameters were frozen for calculations with slab models. The generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional44 was used for all geometry optimizations and energy calculations, in a planewave basis set with an energy cut-off of 500 eV and Gaussian smearing of 0.05 eV. The Hubbard U correction, where U is defined as Ueff, was applied for B metals of perovskites to treat the strong on-site Coulomb interaction of their localized d electrons (Supplementary Table 10)45–47. For calculations of bulks and slabs, the (3 × 3 × 3) and (3 × 3 × 1) Monkhorst−Pack48 meshes were used for the k-point samplings, respectively. The convergence thresholds for the electronic structure and forces were set to be 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV Å−1, respectively. All calculations were performed using the VASP code49. More details of the computations can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Dane Morgan, Professor Jin Suntivich, Dr Ryan Jacobs, Professor Xinghua Xia, and Professor Di Wu for insightful discussion, as well as anonymous reviewers for critical and constructive comments. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (21874067, 21722503, and 11874199), 973 Program (2015CB659400 and 2015CB654901), PAPD program, Shuangchuang Program of Jiangsu Province, Open Funds of the State Key Laboratory of Analytical Chemistry for Life Science (SKLACLS1704), Open Funds of the State Key Laboratory of Coordination Chemistry (SKLCC1819), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (021314380103), and Thousand Talents Program for Young Researchers.

Author contributions

H.W. and X.W. designed the experiments. X.W. prepared the catalysts, performed the structural characterization, steady-state kinetics measurements, and analyzed the data. X.J.G. and X.G. conducted the DFT calculations and analyzed the DFT data. L.Q. assisted with catalysts preparation, structural characterization, and peroxidase-like activity measurements. C.W. and L.S. carried out XAS measurements. G.Z. and Z.J. performed the characterization of N2 adsorption–desorption. Y.-N.Z., W.C., S.L., L.Z., K.W., H.Z. and P.W. assisted with the structural characterization. X.W., X.J.G., X.G., and H.W. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all the authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

H.W., X.W., and L.Q. are co-authors on patent applications. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiaoyu Wang, Xuejiao J. Gao.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-08657-5.

References

- 1.Gao LZ, et al. Intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:577–583. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan KL, et al. Magnetoferritin nanoparticles for targeting and visualizing tumour tissues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:459–464. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonga GY, et al. Supramolecular regulation of bioorthogonal catalysis in cells using nanoparticle-embedded transition metal catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natalio F, et al. Vanadium pentoxide nanoparticles mimic vanadium haloperoxidases and thwart biofilm formation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:530–535. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manea F, Houillon FB, Pasquato L, Scrimin P. Nanozymes: gold-nanoparticle-based transphosphorylation catalysts. Angew. Chem. -Int. Ed. 2004;43:6165–6169. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Zhang X, Liu B, Liu J. Molecular imprinting on inorganic nanozymes for hundred-fold enzyme specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5412–5419. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huo M, Wang L, Chen Y, Shi J. Tumor-selective catalytic nanomedicine by nanocatalyst delivery. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:357. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soh M, et al. Ceria-zirconia nanoparticles as an enhanced multi-antioxidant for sepsis treatment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:11399–11403. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JP, Patil S, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Rare earth nanoparticles prevent retinal degeneration induced by intracellular peroxides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2006;1:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue T, et al. Integration of molecular and enzymatic catalysts on graphene for biomimetic generation of antithrombotic species. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3200. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao N, et al. Transition-metal-substituted polyoxometalate derivatives as functional anti-amyloid agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3422. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugan LL, et al. Carboxyfullerenes as neuroprotective agents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12241–12241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12241-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vernekar AA, et al. An antioxidant nanozyme that uncovers the cytoprotective potential of vanadia nanowires. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5301. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei H, Wang EK. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): next-generation artificial enzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:6060–6093. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35486e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo YJ, et al. Hemin-graphene hybrid nanosheets with intrinsic peroxidase-like activity for label-free colorimetric detection of single-nucleotide polymorphism. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1282–1290. doi: 10.1021/nn1029586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Song J, Duan X, Mu J, Wang Y. Perovskite LaCoO3 nanoparticles as enzyme mimetics: their catalytic properties, mechanism and application in dopamine biosensing. New J. Chem. 2017;41:8554–8560. doi: 10.1039/C7NJ01177F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng H, et al. Integrated nanozymes with nanoscale proximity for in vivo neurochemical monitoring in living brains. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:5489–5497. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W, et al. Prussian blue nanoparticles as multienzyme mimetics and reactive oxygen species scavengers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5860–5865. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan DM, et al. Nanozyme-strip for rapid local diagnosis of Ebola. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015;74:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, et al. Boosting the peroxidase-like activity of nanostructured nickel by inducing its 3 + oxidation state in LaNiO3 perovskite and its application for biomedical assays. Theranostics. 2017;7:2277–2286. doi: 10.7150/thno.19257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suntivich J, et al. Design principles for oxygen-reduction activity on perovskite oxide catalysts for fuel cells and metal-air batteries. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:546–550. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima FHB, et al. Catalytic activity-d-band center correlation for the O2 reduction reaction on platinum in alkaline solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:404–410. doi: 10.1021/jp065181r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamenkovic VR, et al. Trends in electrocatalysis on extended and nanoscale Pt-bimetallic alloy surfaces. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:241–247. doi: 10.1038/nmat1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suntivich J, May KJ, Gasteiger HA, Goodenough JB, Shao-Horn Y. A perovskite oxide optimized for oxygen evolution catalysis from molecular orbital principles. Science. 2011;334:1383–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1212858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Yin X, Tsao KC, Fang S, Yang H. Ca2Mn2O5 as oxygen-deficient perovskite electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14646–14649. doi: 10.1021/ja506254g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou S, et al. Engineering electrocatalytic activity in nanosized perovskite cobaltite through surface spin-state transition. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11510. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, et al. Ultrafine NiO nanosheets stabilized by TiO2 from monolayer NiTi-LDH precursors: an active water oxidation electrocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:6517–6524. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao B, et al. A tailored double perovskite nanofiber catalyst enables ultrafast oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14586. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammer B, Norskov JK. Why gold is the noblest of all the metals. Nature. 1995;376:238–240. doi: 10.1038/376238a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greeley J, Jaramillo TF, Bonde J, Chorkendorff IB, Norskov JK. Computational high-throughput screening of electrocatalytic materials for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2006;5:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nmat1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seh ZW, et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science. 2017;355:eaad4998. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulkarni A, Siahrostami S, Patel A, Norskov JK. Understanding catalytic activity trends in the oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:2302–2312. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YL, Kleis J, Rossmeisl J, Shao-Horn Y, Morgan D. Prediction of solid oxide fuel cell cathode activity with first-principles descriptors. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2011;4:3966–3970. doi: 10.1039/c1ee02032c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs R, Mayeshiba T, Booske J, Morgan D. Material discovery and design principles for stable, high activity perovskite cathodes for solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8:1702708. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201702708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Man IC, et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem. 2011;3:1159–1165. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201000397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calle-Vallejo F, et al. Finding optimal surface sites on heterogeneous catalysts by counting nearest neighbors. Science. 2015;350:185–189. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vojvodic A, Norskov JK. Optimizing perovskites for the water-splitting reaction. Science. 2011;334:1355–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1215081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seitz LC, et al. A highly active and stable IrOx/SrIrO3 catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Science. 2016;353:1011–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen XM, et al. Mechanisms of oxidase and superoxide dismutation-like activities of gold, silver, platinum, and palladium, and their alloys: a general way to the activation of molecular oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:15882–15891. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimaud A, et al. Double perovskites as a family of highly active catalysts for oxygen evolution in alkaline solution. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2439. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, X., Guo, W., Hu, Y., Wu, J. & Wei, H. Nanozymes: Next Wave of Artificial Enzymes (Springer, 2016).

- 42.Cai R, et al. Single nanoparticle to 3D supercage: framing for an artificial enzyme system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:13957–13963. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H, et al. Promoting photochemical water oxidation with metallic band structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1527–1535. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee YL, Gadre MJ, Shao-Horn Y, Morgan D. Ab initio GGA plus U study of oxygen evolution and oxygen reduction electrocatalysis on the (001) surfaces of lanthanum transition metal perovskites LaBO3 (B = Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:21643–21663. doi: 10.1039/C5CP02834E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee YL, Kleis J, Rossmeisl J, Morgan D. Ab initio energetics of LaBO3 (001) (B = Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni) for solid oxide fuel cell cathodes. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:224101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.80.224101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Maxisch T, Ceder G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA + U framework. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:195107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.195107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monkhorst HJ, Pack JD. Special points for brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B. 1976;13:5188–5192. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.13.5188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kresse G, Furthmuller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169–11186. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.